THE VOICE OF INTERNATIONAL LITHUANIA

|

VilNews has its own Google archive! Type a word in the above search box to find any article.

You can also follow us on Facebook. We have two different pages. Click to open and join.

|

Ona Šimaitė:

Righteous – and Human

Julija Šukys,

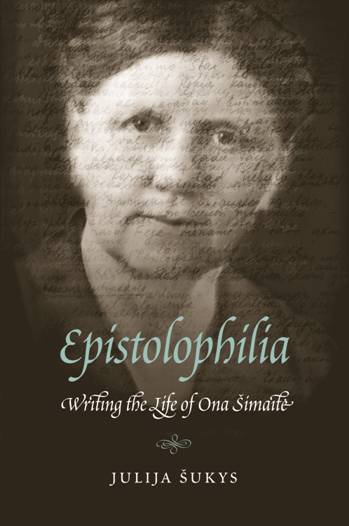

Author of Epistolophilia: Writing the Life of Ona Šimaitė

Julija Šukys interviewed by Ellen Cassedy

In her new book, Epistolophilia, Julija Šukys follows the letters and journals—the “life-writing”—of Ona Šimaitė (1894–1970), a Lithuanian librarian who again and again slipped into the Jewish ghetto of German-occupied Vilnius carrying food, clothes, medicine, money, and counterfeit documents. Often she left with letters to deliver, manuscripts to hide, and even sedated children swathed in sacks. In 1944 she was captured by the Gestapo, tortured for twelve days, and deported to Dachau.

Šukys beckons back to life this quiet and worldly heroine. Ona Šimaitė is a giant of Holocaust history – one of the “Righteous among the Nations” honored at the Yad Vashem memorial in Israel – and yet little known.

Julija Šukys lives in Montreal, Canada. In addition to Epistolophilia, she is also the author of Silence Is Death; The Life and Work of Tahar Djaout. Visit her website at http://julijasukys.com.

What led Šimaitė to become a rescuer?

This is perhaps one of the most difficult questions to answer. What leads some people to behave in one way, and others differently? Where do such convictions and courage come from?

Šimaitė rarely addressed the question of why she did what she did, perhaps because she couldn’t imagine behaving otherwise, so to her mind there was nothing to explain. She once wrote that she simply acted out of a “feeling of humanity and comradery.”

Initially, her motivations were perhaps personal: after saying tearful goodbyes to friends as they prepared to leave for the ghetto, she searched for a way to penetrate its security to visit them. Once she started to visit the ghetto regularly, her mission broadened, and she began to undertake helping anyone she could.

Šimaitė lived according to a strict moral code – she never lied, she abhorred the feeling of indebtedness or dependence, and she absolutely rejected the pursuit of wealth or material gain. This code and a strong individualism are what defined the choices she made in her life.

Šimaitė is hailed as a heroine, yet you present her as a flawed human being.

I set out to create a nuanced portrait of a woman who acted with astounding courage, but who was nevertheless human. Early in my research, I came across a letter that Šimaitė concluded by writing, “love me with all my faults.” “What faults?” I wondered, “What is she referring to?” But, of course, we all have faults. They are what make us human. Šimaitė’s deep sense of compassion and capacity for forgiveness came from her understanding of this fact.

Some say the rescuers were saints, yet we learn from your book that Šimaitė would have hated being beatified. Why?

I imagine Šimaitė found it difficult to take pride in saving those she did since so many others perished, including some people very close to her. Perhaps her acts of resistance seemed to be drops that just disappeared into a vast ocean of tragedy and cruelty.

Šimaitė was tortured and confined in the camp at Dachau, yet didn’t want to talk or write about that. Can you share your thoughts on how a person – or a nation – engages with painful memories?

Šimaitė’s experience at Dachau constitutes the great silence in her writing and life. With the exception of a handful of passing references in her letters and diaries, she breathed nothing of her time there. Though I’m no psychologist, I believe this silence is indicative of a very deep trauma. For her, Dachau marked the limit of what was sayable and writeable.

In the end I decided not to try to fill Šimaitė’s silence, but to write around it, and give an image of how her camp experiences echoed throughout the rest of her life. I suppose you could say I tried to create a kind of chalk outline of her camp experience. The book traces the limits of that experience, but doesn’t try to fill in the void. I chose to respect her right to silence, and to consider silence itself as a subject worthy of contemplation.

In your book, you say you’re engaged in a conversation with Šimaitė. Can you tell us more?

I went to the archives looking for answers to questions about the Holocaust in Lithuania – the country of my parents and grandparents – and came across an incredible and largely untouched collection of Šimaitė’s papers. I was a person with a curious skill set (knowledge of Lithuanian, French, German, Russian; training in literary criticism) that seemed perfectly matched to writing Šimaitė’s life story.

I felt as if Šimaitė had foreseen my arrival, and that she’d prepared for it by saving and archiving her papers. In undertaking the project, we entered into an agreement: in return for my telling her story, Šimaitė would answer some of the questions that had been nagging at me.

Finally, can you describe for us your connection to Lithuania?

Lithuanian was the language of my childhood. I grew up speaking the language at home in Toronto, and I learned to read and write it by attending Saturday schools. Beyond life itself, a knowledge of their language is perhaps the greatest gift my parents gave me.

I’ve been to Lithuania many times, and my relationship to that place is simultaneously one of belonging and alienation. Though I get great pleasure from speaking Lithuanian in shops and restaurants, and though I experience a sense a connection to my ancestors when I walk through the fields they once worked, I nevertheless feel that I don’t really belong there. It may be that writing about Lithuania is a way for me to work through these conflicting sensations.

Now, my relationship to Lithuania and its language is increasingly textual. Like Šimaitė, I spend much of my time alone, with books, and conversing with the dead through their writings and in my imagination.

|

Ellen Cassedy |

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

VilNews e-magazine is published in Vilnius, Lithuania. Editor-in-Chief: Mr. Aage Myhre. Inquires to the editors: editor@VilNews.com.

Code of Ethics: See Section 2 – about VilNews. VilNews is not responsible for content on external links/web pages.

HOW TO ADVERTISE IN VILNEWS.

All content is copyrighted © 2011. UAB ‘VilNews’.

Click on the buttons to open and read each of VilNews' 18 sub-sections

Click on the buttons to open and read each of VilNews' 18 sub-sections

What a superb interview. It's clear both interviewer and interviewee are deeply engaged with the subject matter. Cassedy's questions elicited greater insights into the author and her subject than I've read or heard to date, and I've been following this wonderful book closely. The depth of research Sukys carried out and the beautifully crafted portrayal she offers of this incredible woman's story are as inspiring to me as Simaite was to her.

[…] Read more… Category : Front page […]