THE VOICE OF INTERNATIONAL LITHUANIA

|

VilNews has its own Google archive! Type a word in the above search box to find any article.

You can also follow us on Facebook. We have two different pages. Click to open and join.

|

Dear readers,

On 15 June 1940, Soviet Russia invaded Lithuania. This was the beginning of Lithuania’s loss of freedom for more than fifty years and the beginning of one of the saddest and most tragic parts of Lithuania’s history. There has been much talk and speculation about how this invasion came about and what Lithuania did, or as some would accuse didn’t do, to prevent it. To shed clear light on this topic, we would like to share with you parts of the personal memoirs of Juozas Urbšys who was a member of the group that personally met with Vyacheslav Molotov and Stalin. After reading these fascinating and very informative memoirs we are sure you will have a better appreciation for the precarious situation the leaders of the then free Republic of Lithuania were in and what they did to try to protect the lives of the Lithuanian people.

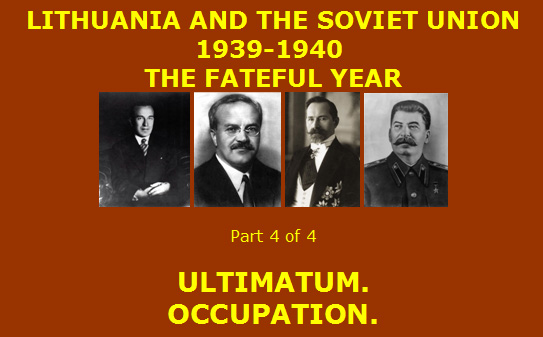

We will share these memoirs in 4 parts. Here is part 4 of 4

ULTIMATUM.

OCCUPATION.

p. 28

The Lithuanian government decided to send its Minister of Foreign Affairs to Moscow to find out once and for all what was expected of Lithuania. Pozdniakov was appraised of this. After several days, Natkevičius telegraphed from Moscow that Molotov wished to speak with the Prime Minister.

On June 7, Prime Minister A. Merkys arrived in Moscow where he stayed until June 12. During that time he had several meetings with Molotov. The latter had invented yet another accusation: Lithuania, apparently, had entered into a military agreement with Latvia and Estonia against the Soviet Union. What an empty fabrication! Estonia and Latvia, at the beginning of their independence, had entered into a mutual military agreement, openly declared and known to all, including the Soviet Union which had concluded mutual assistance treaties with both countries. Lithuania, however, had never been party to the Estonian/Latvian military convention, nor had it made any other war treaty with them.

On June 11, the government of Lithuania sent its Minister of Foreign Affairs to aid A. Merkys. That same evening we were received by Molotov. We explained that now, as always, and especially in view of the international situation, Lithuania sought friendly relations with the Soviet Union based on reciprocal loyalty and fidelity to treaties. Molotov was not the least bit interested in listening to our speech.

A. Merkys flew to Kaunas on June 12, leaving me in Moscow.

Prime Minister Antanas Merkys

Minister Plenipotentiary Natkevičius and I try knocking on other doors in hopes of getting some clarification elsewhere. To this end we visit Assistant Deputy People's Commissar for Foreign Affairs, Dekanozov, who would later direct Lithuania's annexation and who would be shot together with Beria after the Second World War.

I question him about the matter concerning us, hoping to ascertain what it was that the Soviet Union expected of Lithuania.

— The matter is now in government hands and I, personally, can do nothing, — was Dekanozov's answer.

I had brought with me a letter from the President of the Republic of Lithuania, Antanas Smetona, addressed to the chairman of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the Soviet Union, Mikhail Kalinin. In the letter, President Smetona solemnly asserts Lithuania's fidelity to traditional friendly relations between the two countries and states that Lithuania has no overt or covert commitments to any third nation which would not be compatible with such relations or with any Lithuanian/Soviet treaties.

"The government of the Republic of Lithuania and I, personally, had always made, and will continue to make, a concerted effort so that the treaty of October 10, 1939 will be most faithfully executed," wrote the President of Lithuania.

Minister Natkevičius and I requested a meeting with M. Kalinin to which he agreed. We gave him the letter. After reading it, this high-ranking Soviet official replied with something akin to:

— These issues are now under consideration by the government of the Soviet Union and I cannot interfere.

* * *

Ca-ta-stro-phe!

Let us remember a moment of the late evening meeting of October 3, 1939 in the Kremlin when Stalin declared to the Lithuanian delegation that the Soviet Union and Germany had agreed to divide up Lithuania and Molotov had talked of "new ways." New ways, indeed. Now it becomes clear that these new ways were paved for the same old purpose — so that hobnailed boots could trample foreign soil.

Midnight on June 14, Molotov summons us to the Kremlin. Natkevičius and I go.

— I have an important announcement for the government of Lithuania, — states Molotov picking up a written message from the table and reading it.

It was the worst kind of ultimatum. Worst in the sense that normally an ultimatum in international affairs means a categorical demand, precluding any further arguments or contradictions, which one country makes to another threatening the use of military force if its demands are not met within the time frame set by the ultimatum. This document, as we will see, was written in such a way, and further clarified by Molotov in words which would leave no doubt or hope, that no matter what concessions Lithuania made, the Soviet Union would still occupy it with its military might.

The first part of the ultimatum deals with reprimands, the second with demands.

The reprimands are divided into two paragraphs. The first harshly repeats the Soviet Union's version of the alleged abduction of Soviet soldiers, now clearly affirming that this was carried out by institutions of the Lithuanian government. That same paragraph mentions "mass arrests and deportations to concentration camps of Lithuanian citizens among whom are those individuals who serve Soviet army troops." All of these allegations are one-sidedly presented as facts which show that "the government of Lithuania grossly violates" the treaty of mutual assistance and is "preparing to attack (!) Soviet army bases established according to that treaty."

The second paragraph of the reprimands ascertains that "the government of Lithuania entered into a military alliance with Latvia and Estonia." That fictitious accusation of Molotov's is presented as a fact showing how "the government of Lithuania brusquely" violated Article 6 of the Soviet/Lithuanian mutual assistance treaty.

Had these accusations had some basis in fact, they would have been dealt with according to the procedures set forth in the September 28,1926 treaty of non-aggression between Lithuania and the Soviet Union. Article 5 of that treaty clearly states that in the event of a conflict arising between the two countries, and one which they could not resolve by diplomatic means, that Lithuania and the Soviet Union would appoint the necessary commissions. Hence, the Soviet Union, by one-sidedly resorting to military force to purportedly regulate not a real but an artificial conflict of its own making, was the one that grossly violated the treaty of non-aggression, and together with it, all of the other treaties linking the two countries.

This brings to mind the July 5,1933 treaty regarding the definition of an aggressor which stipulated that the use of armed force by one country against the other cannot be justified by that country's "political, economic, or social structure, the faults attributed to its administration, or to unrest arising from strikes ..."

The second part of the ultimatum demands:

"1. That Minister of the Interior Skučas and Director of State Security Povilaitis be put on trial as those directly responsible for the acts of provocation against Soviet garrisons in Lithuania;

General Kazimieras Skučas and Augustinas Povilaitis

2. That a government willing and capable of assuring the conscientious execution of the treaty of mutual assistance between the Soviet Union and Lithuania, and one resolved to suppress the foes of this treaty, be formed at once in Lithuania;

3. That free passage into Lithuanian territory be guaranteed immediately for those Soviet army units which will be situated in the most important centers of Lithuania and which will be large enough to assure the fulfillment of the Soviet/Lithuanian treaty of mutual assistance and the interdiction of the acts of provocation perpetrated against the Soviet garrisons in Lithuania."

All of these demands are clearly contrary to the treaty of mutual assistance which the ultimatum purports to defend, especially to Article 7 which reads:

"The execution of this treaty shall in no way infringe upon the sovereign rights of the contracting countries, and especially their system of government, their economic and social systems, their military means, or generally, the principle of non-interference in internal affairs."

Finally, the time limit for the ultimatum is set forth:

"The government of the Soviet Union expects a response from the government of Lithuania by 10 A.M. on June 15. Non-receipt of a response by that time will be taken to be a refusal to comply with the above-made demands of the Soviet Union."

Having read this aloud, Molotov handed it to me. I read it again silently. What to do? Or say? Stunned silence on my part.

— I am afraid of what this ultimatum means for Lithuania, — I finally say, feeling that these are not the requisite words.

Words? Like peas thrown against a wall.

Molotov cried out angrily:

—You've sold Lithuania right and left enough times! We know how much the fate of Lithuania means to you.

I waited for his effrontery to subside and after a moment asked:

— Wouldn't it be possible to extend the time limit of the ultimatum? It's almost one in the morning. We won't be able to submit it to our government on time. It still had to be coded.

To which Molotov replied:

— It's not necessary to submit the reasons for the ultimatum. The three points can be coded quickly and you should get a response by 10 A.M. Even so, whatever your reply may be, the army will march into Lithuania tomorrow.

(Tomorrow . . . Not tomorrow, today. Tomorrow had already begun . . . )

We return to the legation with the document burning a hole in our pockets. We feel dishonored, trampled, violated.

We try telephoning Kaunas and cannot get through. Evidently all the lines are busy. There is no time to code the message. We send the three paragraphs of the demands and the time limit for the ultimatum in an open telegram.

Towards morning our call to Kaunas finally comes through. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs answers. The director of the legal administration department, Voldemaras Vytautas Černeckis, comes to the phone.

— Good morning, — I say, — I have until 10 A.M. to report whether or not the government accepts the Soviet Union's ultimatum. What can I say?

I am not going to try and reconstruct Černeckis's words. The sound of his voice sufficiently echoes the tragedy of the situation. I feel that my question, too, must sound strange to his ears, almost incomprehensible. It's as if he were saying: "What kind of talk can there be about acceptance or refusal? That doesn't change a thing. The Soviet army is still going to march into Lithuania."

Finally, in a tired and dispirited voice, he says:

— It accepts.

This would be an apt place to honor the memory of this noble patriot. He had married a Lithuanian woman from America and they had raised a large and handsome Lithuanian family. Because she was born in the U.S., his wife had the right to become an American citizen, and through their marriage, so did he. When the Soviet Union occupied Lithuania, the U.S. Embassy offered to issue them American passports so that they and their family could go to the States. Černeckis, however, was unwilling to leave his country in its time of misfortune and stayed in Lithuania. Unfortunately, not for long. The newcomer Soviets deported him and his entire family to Siberia. There they incarcerated him in a camp where he died. "Assuring" the "fulfillment" of the non-aggression treaty, they deported his wife and four children beyond the Arctic Circle to the mouth of the Lena River.

On the morning of June 15, Natkevičius and I ask to see Molotov. After a bit, the phone rings:

— Molotov awaits you.

Molotov and Pozdniakov receive us. I say:

— The government of Lithuania accepts your ultimatum.

— Good, — says Pozdniakov, and raising his tone of voice, he adds — But your government continues to carry out policies hostile to ours. We've just received word that it has named Raštikis as the new Prime Minister. How can you name a new prime minister without our knowledge or our consent?

— But you have demanded that a new government be formed ... — I try to explain.

— True, but it has to be acceptable to us. That's why you must confer with us about its composition.

(...)

(Here Urbšys reiterates Article 7 of the mutual assistance treaty and its specification of non-interference in internal affairs.)

p. 33

And now look — Lithuania, a sovereign nation, can not even form its own government without the Soviet Union's approval.

— Very well, — continues Molotov in a calmer tone, — our special emissary will leave for Lithuania today. I still don't know who it will be.

He stares at me for a while thinking something to himself.

— Your president will have to confer with him about the composition of the new government. With him and with comrade Pozdniakov, — finishes Molotov.

The above-mentioned Dekanozov, Deputy People's Commissar for Foreign Affairs, was named that special emissary.

We telegraphed Kaunas of what we have heard from Molotov. Natkevičius says:

— Why not add that Skučas and Povilaitis not try to escape? Why should they be afraid of a trial? Their escape would only appear to be an admission of guilt.

So we telegraphed it ... How naive we still were . . . We thought that, all of this notwithstanding, Lithuania would remain an independent nation. Natkevičius supposed that it would be accorded the status that Mongolia had at the time. We presumed Lithuanian courts would publicly consider the case of Skučas and Povilaitis. The first paragraph of the ultimatum even required that they be put on trial. By ordering the arrest of these two individuals, Prime Minister Merkys was carrying out the demands of the ultimatum. And who heard about any such trial, or even about their fate? — They disappeared into the depths of the NKVD's labyrinths never to resurface. (Author's note, p. 34: "Skučas and Povilaitis were apprehended near the Prussian border, jailed and later executed," in Jerzy Ochmanski, Historia Litwi, 1967)

On June 15, in Moscow's grand theater, the final performance celebrating the decade of Byelorussia was being put on. Natkevičius asked whether or not we were going. I replied in the negative. Nonetheless, Natkevičius tried to persuade me to go by arguing that such a demonstration would be pointless.

We went. I was given a seat in the loge next to German Ambassador von Schulenburg, though whether this was for reasons of protocal or for others, I do not know.

Since I am to leave tomorrow, it would be fitting to pay a farewell visit to Molotov. The legation phoned the Protocol Department which quickly returned the call saying that although Molotov was to be at a reception in the Kremlin honoring the Byelorussians he would absent himself briefly to receive me at 11:30 in the evening.

Once again we went to the Kremlin for what would be, at least for me, the last time. Molotov, having left the reception, received us in good spirits. For some reason, he asked my opinion about Justas Paleckis. I replied that the man seemed to me a sincere Lithuanian patriot. I knew nothing then, nor could I have guessed, of the role which the Kremlin had foreseen for Justas Paleckis.

As he bid us farewell, Molotov looked attentively at Natkevičius and me, saying:

— The two of you will be able to work in the new system.

—Thank you.

Molotov now feels totally the master of Lithuania. And why not, considering how many troops he's crammed in there? As a Russian, he knows yog kto palku vzial tot i kapral or in the approximate Lithuanian version, the one holding the cudgel chases who he wants to.

The following morning, the 16th of June, I am on a Swedish passenger plane to Riga. The closer we get to Latvia the more Soviet fighter planes there are in the sky. On the same day that the Soviet Union occupied Lithuania its armies also took over Latvia and Estonia. Two fighters approach our plane, one on either side, and instruct us to land. We follow them to a military airfield and some sort of official alights from our plane. The rest of us wait. After about fifteen minutes he returns and we are airborne once again.

In Riga, I change to a train.

Soon I will be in Lithuania, my one and only, my dear and beloved country……

Photo courtesy of Lituanus

DEKANOZOV TAKES COMMAND OF LITHUANIA

p. 35;

The airport of Šiauliai is abuzz with Soviet military aircraft. At Kėdainiai, a "mutual assistance" tank partially protrudes from behind the station house.

How dismal. Past Jonava, several of the ultimatum's tanks rattle along a rye field path to the highway……

We would like to thank Lituanus for their kind permission to share this article with you.

LITUANUS

LITHUANIAN QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES

Volume 34, No. 2 - Summer 1989

Editor of this issue: Antanas Dundzila

Memoirs of Juozas Urbšys

Translated and edited by Sigita Naujokaitis

http://www.lituanus.org

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

VilNews e-magazine is published in Vilnius, Lithuania. Editor-in-Chief: Mr. Aage Myhre. Inquires to the editors: editor@VilNews.com.

Code of Ethics: See Section 2 – about VilNews. VilNews is not responsible for content on external links/web pages.

HOW TO ADVERTISE IN VILNEWS.

All content is copyrighted © 2011. UAB ‘VilNews’.

Click on the buttons to open and read each of VilNews' 18 sub-sections

Click on the buttons to open and read each of VilNews' 18 sub-sections

[…] Part 1: In Moscow Part 2: Vilnius, army garrisons Part 3: We accustom ourselves to army bases. Part 4: Ultimatum. Occupation. […]

[…] 1: In Moscow Part 2: Vilnius, army garrisons Part 3: We accustom ourselves to army bases. Part 4: Ultimatum. Occupation. Category : Featured / Historical […]