THE VOICE OF INTERNATIONAL LITHUANIA

|

VilNews has its own Google archive! Type a word in the above search box to find any article.

You can also follow us on Facebook. We have two different pages. Click to open and join.

|

Dr. Jonas Sliupas (1861 – 1944)

The year is 1926. It is a very dark late autumn evening in Kaunas, Lithuania's capital between 1st and 2nd World Wars, when three officers from the Lithuanian army rush up to the house where Dr. Jonas Sliupas now lives while he teaches at the University of Kaunas. It is nearly midnight when the officers knock heavily on his door and asks to come inside.

The officers bring shocking news. They tell that since the early autumn of 1926 key officers within two army groups have been in full swing of planning a coup d’état in Lithuania, and that they have now reached the point that they want to depose of President Kazys Grinius and insert a new President. The question to Dr. Sliupas is therefore whether he can accept becoming the country's new President.

But Dr. Sliupas is not willing to accept. President Grinius has been his good friend for many years, and Sliupas is puzzled as to why the military has found a coup appropriate and necessary. His answer to the officers is therefore that the only way he could accept becoming President of Lithuania would be through a democratic election.

The officers had to leave Sliupas empty-handed that night, but continued their plans, and the very coup took place a few days later, during the very night when the 60th birthday of President Grinius was celebrated, 17 December 1926.

During that night, military forces occupied central military and government offices and arrested officials. Colonel Kazys Škirpa, who had initiated a military reform programme tried to rally troops against the coup, but was soon overpowered and arrested. The Seimas (Parliament) was dispersed and President Grinius was placed under house arrest at the same time as army colonel Povilas Plechavičius was declared dictator of Lithuania just minutes after he had been released from the prison cell where he was serving a 20-day sentence for a fist fight with another officer.

Later that same day, however, Colonel Plechavičius asked Antanas Smetona to become the new President of Lithuania.

The 1926 Lithuanian coup d'état (Lithuanian: 1926-ųjų perversmas) was a military coup that resulted in the replacement of the democratically elected government with a conservative authoritarian government led by Antanas Smetona.

|

|

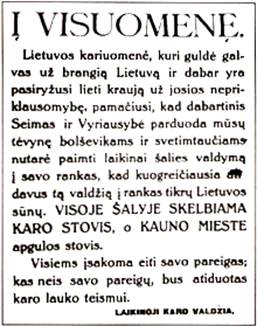

TO THE PUBLIC

Lithuanian army, which sacrificed lives for dear Lithuania and is still ready to spill blood for its independence, seeing that the current Seimas and government are selling Lithuania to Bolsheviks and foreigners decided to temporarily take the power in its hands so that the power could be transferred as soon as possible to real sons of Lithuania. MARTIAL LAW IS DECLARED IN THE ENTIRE COUNTRY, and siege law in KAUNAS. Everybody is commanded to go about their duties; those who will not do their duties will be tried in military tribunal.

TEMPORARY WAR GOVERNMENT

|

|

A pamphlet distributed in Kaunas following the coup declared martial law and commanded everyone to go about their daily duties. It was signed by the Temporary War Government.

|

|

One can rightly ask what kind of Lithuania we would have had if Dr. Jonas Sliupas had not declined the Presidency that late autumn night. But in view of his human qualities and his extraordinary life story from both the United States and Lithuania, it is no wonder that this honourable man declined the Presidency and instead chose to continue his tireless fight for his beloved homeland, with important titles and tasks in the years leading up to World War II, but not as the country's top figure as the country's military leaders had wanted.

During his remarkably productive lifetime, Jonas Sliupas was a medical doctor, a leader of Lithuania's national awakening, a powerful orator and organizer, a writer of numerous articles on Lithuanian politics, economy, culture, and medicine, a historian, a diplomat, a free-thinker, and a publisher of seven newspapers. He also served as the author or translator of over 70 books and was a pioneer in helping develop and modernize Lithuania's economy.

Jonas Sliupas was born on the 6th of March 1861 in the village of Rakandziai in northern Lithuania. In 1880, he graduated with honours from Mintauja (Jelgava) high school. Next, he studied philology and law at Moscow University and later transferred to Saint Petersburg University to study natural science. Because of his participation in the student anti-czarist movement, however, Sliupas was incarcerated in 1883 and was banned from further studies at any Russian university.

The Russian government banned all books and newspapers in the Latin alphabet in Lithuania from 1864 to 1904. Consequently, Sliupas joined with others to publish an underground Lithuanian language nationalist newspaper, which was smuggled into Lithuania from outside. Together with Dr. J. Basanavicius and three other idealists, Sliupas published and edited the clandestine newspaper Ausra (Dawn) in Lithuania Minor from 1883 to 1884. Ausra, whose very name was suggested by Sliupas, is considered to be the driving force behind the Lithuanian nationalist awakening of the late nineteenth century.

Because of his ongoing nationalist activities, both Prussian and Russian police began pursuing him. Facing imminent arrest, Sliupas had to flee to the United States in 1884, where he would remain until 1918. He began studying at the University of Maryland in Baltimore in 1889 and graduated with a degree in medicine in 1891.

Dr. Sliupas was very active among Lithuanian-American immigrants, helping inspire in them a deep sense of national pride in their ancestral homeland. Although he was a free-thinker, he nevertheless helped establish several Lithuanian Roman Catholic parishes. He also invited Lithuanian priests to the Unites States and worked with them to promote a strong sense of Lithuanian ethnic and cultural identity among the parishioners. Being a powerful, inspiring, and uncompromising orator, Sliupas travelled extensively throughout the United States, delivering rousing speeches in which he urged Lithuanian Americans to unite in order to help Lithuania regain its independence.

Sliupas also edited newspapers and wrote or translated numerous books. Fluent in eight languages, he wrote thousands of articles both about Lithuania itself and about various medical topics for Lithuanian, American, Polish, German, Swedish, British, French and Russian newspapers. He also helped dozens of Lithuanian-American societies, several of which still are in existence today.

During World War I, Sliupas vigorously lobbied the United States government for diplomatic recognition an economic support for Lithuania. Having established a personal friendship with U.S. Senator Henry Cabot Lodge, head of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, Sliupas campaigned tirelessly in Washington D.C. for Lithuanian and Latvian independence. In 1918, Sliupas opened the first Lithuanian Legation in London. Then, in 1919, he was with the Lithuanian independence movement at the Paris Peace Conference. After returning to Lithuania, in 1919, he was appointed the first envoy to Latvia and Estonia.

Between 1921 and 1924, Dr. Sliupas taught hygiene and medical history at Birzai and Siauliai high schools. From 1925 to 1929, he lectured at the University of Lithuania in Kaunas. He also worked diligently to encourage investment in Lithuania's economy by investing much of his own savings in the country's economic development. Sliupas was the first mayor of the sea-side resort of Palanga, and he continued intermittently in this position from 1933 until Soviet occupation began in 1940. During June of 1941, he again resumed the role of mayor but was forced by the Germans to resign, because of his attempts to protect Jewish residents of the city.

Dr. Jonas Sliupas died in exile in Berlin, Germany on the 6th of November 1944.

Surviving family members transported his ashes to the United States, where they are buried in the Lithuanian National Cemetery near Chicago, Illinois.

Dr. Jonas Sliupas has been recognized numerous times for his life-long dedication to Lithuania's nationalist awakening and its restoration of independence. Among many other honours, Sliupas received three Honorary Doctorates from the University of Vytautas the Great in Kaunas. These include a doctorate in Medicine (1923), one in Humanities (1925), and one in Law (1939). Many organizations, both in Lithuania and in the United States, have declared him an honorary member. The Lithuanian government bestowed upon Sliupas the Gediminas First and Second Order medals. The Latvian government honoured him with the Three Star Second and Third Order medals, and the Lithuanian Post Office issued two stamps in his honour.

Jonas Sliupas will be celebrated as one of Lithuania’s true heroes and finest gentlemen ever, with an amazing record of achievements for his beloved homeland.

|

LITUANUS LITHUANIAN QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES Volume 37, No.1 - Spring 1991 ISSN 0024-5089 |

|

DR. JONAS ŠLIŪPAS (1861-1944)

Sister VIRGINIA MARIE VYTELL, CJC

Because it is true that "there is some bad in the best of us, and some good in the worst of us," the biography of Dr. Jonas Šliūpas written by the Lithuanian historian, Dr. Juozas Jakštas, shows both sides of a controversial figure.

Many people who have never met Dr. Jonas Šliūpas, or knew him superficially, regarded him "an anti-clerical atheist". The truth was not fully known, nor were answers provided to many questions. That Dr. Jonas Šliūpas loved his fellowmen and did everything possible within his power to show that love is seen throughout the pages of the book in Lithuanian.

The following excerpts in English based on the information found in the biography, is an attempt to reveal the side unknown to most Lithuanians in the United States, especially to those living in Northeastern Pennsylvania.

While yet a child in Lithuania Jonas was saddened because there were no more Lithuanian books for him to read. He told his mother that when he grew up he would write, and write, and write some more, until there were plenty of Lithuanian books for everyone. The parents of Jonas, hoping he would become a priest, sent him to his uncle's rectory to continue his education. This was the first far-reaching mistake.

A sensitive boy of a sanguine temperament, forced to live a severly disciplined life with a polonized uncle, Rev. A. Šliūpavičius, he had to study and pray in Polish, and to earn his education as a servant in the rectory. Many times he was tempted to run away from the unbearable situation. As a result it was here that the roots of an anti-clerical ideology were planted. Respect for the priesthood was destroyed. At the age of eleven he became a young skeptic displaying a rebellious spirit toward the clergy.* In 1873 when Jonas was 12 years of age, he was sent to study at a German School in Mitau (Jelgava) in central Latvia. His mother encouraged him to become a man of learning. "Son," she said, "we are poor villagers, uneducated people, that is why we are pushed around by others. As your parents we want you to attend school that you in turn would defend the under-privileged."

At Mitau Jonas remembered his mother's words. He observed the Latvians in their song festivals, attending Latvian theaters, and preparing cultural conventions. The Polish students had their own organizations and Polish books. With the support of wealthy barons had outings and entertainments.

Lithuanians, on the other hand, were not outstanding among the other groups.

No one paid any attention to them, neither the Church nor the School. The oppressive burden of non-recognition weighed heavily upon them and was a source of discouragement for the Lithuanian students. They had no Lithuanian activities. The majority were not wealthy. No one was there to inspire them with a self-assertive spirit or to raise their self-esteem as members of a nation with a long and glorious past.

Jonas was disturbed over the negative reality of the situation. It was then that he formed closer ties with leaders among the Latvians. He saw that Lithuanians and Latvians had more in common through similarities in their language and ethnicity than Lithuanians had with Polish.

In 1880 J. Šliūpas enrolled at Moscow University when Socialism, coming from Western Europe, strongly influenced the idealistic students. He identified with the radical stream. Often meeting with the Lithuanian students he was one of the founders of a student organization as the first of its kind, having its own newspaper, appropriately called Aušra, The Dawn.

In 1882 J. Šliūpas transferred to the University of St. Petersburg where his troubles started. He was arrested and imprisoned for three months for participation in a student riot. The following year, in keeping with his desire to be a writer, he evolved as one of the originators and editors of the Lithuanian newspaper in East Prussia, offering it the name Aušra.

The efforts of young Šliūpas to revive the Lithuanian language and culture were criticized in the Polish press. Šliūpas tried to reason with the Polish editor that love for one's own cultural heritage was not an expression of hatred for Polish. Both could exist as separate and equal entities.

As an outgrowth of the Lithuanian Renaissance Movement, Aušra's purpose was to present the nation's past as part of the whole and a model for the future. It presented Lithuania as a separate and independent political and cultural unit equal to other nations.

As editor of Aušra the young zealot deviated toward the liberal and sodalist trend. As a result of this tendency on his part he was dismissed from his position. Undaunted by the act of dismissal he hoped to be of service to Lithuanians in the New World. Through enlightenment and education he would discover the causes of his nation's mistakes and the source of the people's economic poverty and political decline.

At the age of 23, J. Šliūpas left Hamburg on May 28, 1884. He arrived in New York June 16th where he began the second chapter of his life. It was a chapter filled with hard work and incessant poverty, opposition and misunderstanding. As he later admitted in the golden years of his life he made many blunders in the role he assumed in his youth to awaken the Lithuanian people from sleep, to urge them on the path of national resurrection.

He saw as one of the greatest barriers met by Lithuanians in their efforts to revive their ethnic identity was the polonization of the masses through the Polish Church. Arriving in Brooklyn, New York, J. Šliūpas first involved himself with Lithuanians encouraging them to build a church of their own separated from the Poles. He described his hopes in a letter to his fiancee, L. Malinauskaitė:

"You will see, dearest Liudyte, that by the end of this year we will have a Lithuanian priest and a church of our own. The people will sing, 'Pulkim ant kelių' ('Let us fall on our knees') in New York and in Lithuania."

But it would not be as simple a task as he first surmised. As in other Lithuanian colonies in America, early Lithuanians in New York were associating with the Poles, were drawn into their Societies and joined their parishes as many did in Lithuania. A newspaper of their own, like Aušra, was needed to promote the cause of rebirth in a land of freedom.

The young Šliūpas, by offering the sum of $95, persuaded M. Tvarauskas, a polonized boyar who had a printing press in Brooklyn, to accept him as a partner for the publication of a Lithuanian newspaper. He felt this was his destiny in the New World to spread enlightenment and national awareness among Lithuanians.

To attract more subscribers to the newspaper which they called "Unija" (Union) the decision was made-to publish in both Lithuanian and Polish. In its editorial J. Šliūpas diplomatically blamed the nobility of old for Poland's downfall and the exploitation of the masses. However, among other things, he advocated national freedom and separation for smaller nations including Lithuania. This did not please the Poles or polonized Lithuanians.

The idea of separation and autonomy, — especially for Lithuania, — irritated them. They regarded Šliūpas as unfriendly to Poland and, as such, he was suspected of being a Russian spy. When they refused to subscribe to "Unija", M. Tvarauskas decided to publish the paper for Lithuanians alone. The senior publisher's decision was a victory for Šliūpas who hoped to continue the work begun by "Aušra" for the rebirth of Lithuanian consciousness. He had personal satisfaction in the work to which he felt called.

In the next publication Šliūpas wrote that only "Aušra" among the Lithuanian newspapers was in the hands of Lithuania's defenders, but it alone was not sufficient. He mentioned that the main purpose of "Unija" was to unite Lithuanian Societies, strengthen ties with the Fatherland, and to present the necessary conditions for Lithuania to regain her true identity and freedom.

Living frugally in the printery and sleeping in the same bed the two men worked hard for many hours. However, both had their differences. Tvarauskas, being a polonized boyar, understood the polonized mentality and was patient with Lithuanians fraternalizing with the Poles. J. Šliūpas, on the other hand, was uncompromising in his efforts to separate Lithuanians from Polish domination. This eventually led to break in their common efforts in publication.

Although the American historian, Michaelson, and the Lithuanian Encyclopedia, claim that Šliūpas resigned or was dismissed for verbal attacks on the clergy, Professor Jakštas in his book states that "Šliūpas was dismissed for his resistance to Poles." Be as it may, Jonas Šliūpas found himself unemployed, but not for long.

To continue his work for enlightenment J. Šliūpas founded "Lietuvos Mylėtojų Draugija", Friends of Lithuania. The first members were New York's tailors who supplied him with a modest dwelling and a printing press. One of their projects was to be the publication of "The Lithuanian Voice," Lietuviškas Balsas.

Feeling secure as an independent publisher J. Šliūpas sent for his fiancee, L. Malinauskaitė. They were married in 1885. The first issue of "Lietuviškas Balsas," appearing in July, 1885, had 500 subscribers. His wife, Liudmila, as a writer and poet, contributed articles for publication. Their first child, Aldona, called herself a "Lithuanian Voice baby" because she was often placed in an open drawer in the printery when her mother went to work as a seamstress to help support the family.

With the publication of The Lithuanian Voice the Poles soon felt the influence of Jonas Šliūpas as leader in the movement for separation. During the 500 anniversary of Lithuania's Christian Baptism (1387-1887) commemorated in a German Church, a Capuchin monk delivered a homily praising the Lithuanian nation. At the evening banquet a Polish choir offered entertainment, and the speakers consisted of one Pole, one Jew, and three Lithuanians among whom was J. Šliūpas.

Speaking in Polish, J. Šliūpas explained the negative results inflicted upon the Lithuanians when the Polish rulers used Christianity as a pretext to join Lithuania to Poland, and to deprive the people of their language and some of their land. He touched upon the contemporary Poles and their organizations, accusing them of injustice to Lithuanians. He exempted the Polish Socialist Party which, he said, was kindly disposed toward Lithuania.

The talk which Šliūpas delivered was prepared not so much to commemorate the historic event as to point out Poland's harm to Lithuania.

Then a pro-Polish newspaper, "Lithuanian Unity" published in Plymouth, Pennsylvania, aroused the anti-clerical passions of Šliūpas. The heated disputes which circulated in both newspapers, the Lithuanian Voice and Lithuanian Unity spilled over into the homes, meeting halls, and saloons of Lithuanian colonies. Another newspaper, "Saulė" (The Sun) published in Shenandoah, spread pro-Polish propaganda to convince Lithuanian Catholics to remain united with the Polish to retain their Catholic faith.

Rev. Alexander Burba, a pro-Lithuanian pastor in Plymouth who heard of the Šliūpas family in Lithuania, tried to convince Jonas Šliūpas that Lithuanians had enough to contend with in their efforts to regain their ethnic identity without arguing about religious matters. The most important task before them was strengthening their Lithuanian unity, not destroying it.

When subscribers to the "Lietuviškas Balsas" (The Lithuanian Voice) dwindled down from 500 to 100, and the printing press was seized by his creditors, the 28 year old Šliūpas and his family moved to Shenandoah, Pennsylvania in 1888. Convinced by his wife to seek another profession, J. Šliūpas departed in the fall to study medicine in Baltimore at the University of Maryland.

As a student at the University Jonas proved to be a person of gigantic work capacity. He persevered in his studies to receive a doctor's diploma and at the same time he became involved with Lithuanians living in Baltimore.

Calling a large gathering he received cooperation to establish the Lithuanian Education Society on December 22, 1889. It was a continuing attempt on his part to urge Lithuanians to seek freedom and self identity through education and enlightenment.

Before he graduated in 1891, a new arrival from Lithuania, Rev. S.

Pautienas, attacked J. Šliūpas and his Education Society calling it a nest of atheists. The resultant hostility between both men stirred Lithuanians in Baltimore. Šliūpas' sincere desire to educate the Lithuanian people who were deprived so long by their exploiters was not understood or appreciated by many.

Not discouraged by opposition, Dr. J. Šliūpas established branches of the Society in other locations. The first one in February of 1891 was founded in Plymouth through the cooperation of Rev. Alexander Burba, J. Andžiulaitis and J. Paukštys. Others had centers in Shenandoah, Pittston, Mahanoy City, and Philadelphia.

The periodical "Apšvieta" (Enlightenment) as the Society's news-sheet, was published abroad. Its first edition appeared in 1892. Its purpose was to change the thinking and attitudes of the people, and to motivate them to seek freedom and self-expression. He presented education and enlightenment as implements in Lithuania's future mission to spread learning and culture throughout Eastern Europe and Russia.

The young doctor envisioned a bright tomorrow for Lithuania in which truth and justice would prevail in international relations. He believed the time will dawn when the accumulation of arms will no longer be necessary, where the use of force will be replaced with peace and truth. With the formation of an International Tribunal Lithuania would exist without the need for battleships or a large army. Her resources and energy will be spent for her advancement and benefit and for that of the civilized world.

With the leadership of Rev. Alexander Burba, Lithuanians in the United States finally succeeded in joining Catholic Societies in a central Alliance free of Polish intervention. It was open to all Lithuanians of good-will. In a display of trust and acceptance the position of editor to their news media, "Lithuanian Unity", was offered to the free-thinker J. Andziulaitis.

A column was assigned for Dr. J. Šliūpas with the condition that he refrain from disparaging remarks against the polonized clergy.

Catholic leaders joined the Education Society and invited the members to a convention of the Lithuanian Alliance at Plymouth, Pennsylvania, on November 23, 1891. That it was a well-meant and trusting gesture was apparent but it was also a mistake in expecting the impossible. As Rev. Alexander Burba had been told in the past, "Water and oil would sooner mix than Catholics and free-thinkers (who considered the clergy as polonizers) would find common grounds for unity."

With Rev. J. Žilius as next president of the Lithuanian Alliance a new attempt was made to include all Lithuanians in the organization with the condition that religious questions and arguments pertaining to faith be conscientiously avoided. Considering the strength of their private convictions it was a hopeless expectation that such a compromise would last.

On May 21, 1901, at the 16th convention held in Wilkes Barre, Pennsylvania, the members separated into two organizations, one identified as The Lithuanian Catholic Alliance, the other as The Lithuanian Alliance of America.

Dr. J. Šliūpas had shown an interest in Socialism during his student days at Moscow University, it surfaced in 1897 at the time of the Lattimer Massacre where unarmed coalminers were shot during a peaceful demonstration. In a fiery speech he urged Lithuanians to follow the example of other groups to form a Lithuanian Socialist Branch. He suggested their centers be located in Scranton, Philadelphia, Pittsburgh, and Waterbury.

The ardor of Dr. Šliūpas was dampened when Lithuanians were not invited to the Socialist Congress at the Hague in 1904. However, joined by a new arrival from Lithuania, J. Širvydas, he called a Socialist Convention in Newark, New Jersey, on May 21, 1905, to centralize Socialist activities.

First called the Lithuanian Sodalist Party of America, the name was changed to The Lithuanian Socialist Federation. A disagreement over finances and a lack of better information on what Socialism promoted, Dr. J. Šliūpas resigned and the group disbanded.

Disillusioned with the Socialists he entered a new field of activity, that of the Lithuanian Patriots, and continued in active service to the day of his death, arousing Lithuanian consciousness both in America and Lithuania.

From 1915, a mature man of 54, Dr. j. Šliūpas joined the new American Lithuanian Patriots as the leading speaker, promoter, and fund-raiser. While practicing his profession as doctor he moved from one Lithuanian colony to another in order to influence many Lithuanians to work for their Fatherland's political independence.

Dr. Jonas Šliūpas was convinced that the greatest cause of poverty and moral decadence was the people's ignorance. To raise their level of living, education was needed. He contributed his share in newspaper publications, in books, — both original and translated, — and by giving lectures and organizing study groups. He emulated the methods used by other educators to promote his efforts.

Formed in his youth with a liberal world-view, Dr. Šliūpas made no compromises in his life. He upheld the belief that learning and the harnessing of nature's powers would bring blessings to humanity. His writings revealed that he was the product of the 1789 French Revolution. He expressed himself as a global rationalist with humanity's future in mind. As the 19th century leaders of the great liberal movement he believed in a bright future for the world.

Having a fair knowledge of 8 languages including English, Dr. Šliūpas read extensively and translated much of his acquired knowledge into Lithuanian.

However, the majority of Lithuanians who came to Northeastern Pennsylvania have had little or no opportunity for an education in their Fatherland. It stands to reason that in spite of his exalted aims and sincere love for the Lithuanians, Dr. J. Šliūpas was unable to reach the majority of the people who, living a strenuous life as coalminers to feed and clothe their families, had little time left for education for themselves.

Because of the scandalous example of a few clerics, Dr. J. Šliūpas felt inclined to condemn the entire priesthood, — with a few exemptions, — calling them the blight of the nation, a vocation unfit to lead the people, and living for the good of one's own caste.

Those who tried to limit, through slander and criticism, the extent of the doctor's influence, suceeded in making him widely known. The effect was contrary to intent. Dr. J. Šliūpas evolved as a controversial figure, loved and revered as a hero by some, or condemned and rejected by others. It was difficult to be indifferent to him.

Those who knew his past as a student in Lithuania and understood his motives, were not swayed by the polonizers. To them, Šliūpas was a great Lithuanian patriot, a public activist of wide interests, the author of numerous patriotic and social writings which wielded powerful incentives among Lithuanians in the United States to work for Lithuania's ultimate freedom.

According to Dr. J. Jakštas in his book, Dr. Jonas Šliūpas, (page 10) "researchers of Lithuania's past would be considered partial and prejudiced if they did not attribute to Dr. J. Šliūpas a merited place in the history of Lithuania's national rebirth." On the whole, the liberal and anti-clerical propaganda included in the lectures and writings of Šliūpas did not penetrate the masses. Understanding of human nature, with all its imperfections found in any calling or profession, kept the people true to the teachings of their faith.

What really mattered was the gigantic work Dr. J. Šliūpas was able td accomplish on two continents in spite of poverty, the apathy and indifference on the part of some Lithuanians, and the numerous obstacles he had to overcome through hard work and sheer force of will. Because he believed he was called to be a forerunner of Lithuania's rebirth as a nation gave him strength and courage to persevere in his mission.

To the wearied Lithuanian people he planned an improved future. Through knowledge and freedom they would raise their families to value their ethnic treasures. He stressed that knowledge does not replace virtue; there is a greater need for compassion and love. If the principle prevailed, "Do nothing to others you do not want done to yourself," then learning and creativity would turn this world into paradise.

Throughout his life the doctor retained his strong convictions. He held firmly to the two concepts of education and morality as the guiding light to a successful future, that good results would follow the formation of a national and world culture. Education based on moral principles would establish world cooperation for a lasting and blessed peace.

Whatever Dr. Jonas Šliūpas was able to do in his turbulent life he accomplished to the best of his ability. He had been numbered among the poor most of his life yet he did not seek his own welfare but worked for the good of many. That he made mistakes he humbly acknowledged. "But then," he asked, "what forerunner or prophet succeed-ed in avoiding them?"

Concern for Lithuania's welfare was an important priority in the life of Dr.

J. Šliūpas. Those who understood his deep concern hailed him as a symbol of Lithuania's freedom, a renewer of Lithuanian consciousness in America and in Lithuania. He attracted millions who had the same desire for release from foreign domination. He was recognized as one of the founders of Aušra, as a pioneer of the Lithuanian press, a teacher, lecturer, a promoter of progress and freedom.

Sensitive, an individual of a sanguine temperament, he strongly defended his personal views of patriotism. Those who opposed his ideas he regarded as foes of Lithuanianism. It was not without reason that those who did not agree with him labelled him a fanatic, and intolerant of other people's opinions.

His materialistic viewpoints, his attacks on the church and the clergy, were similar to the tactics of the Bolsheviks, yet the doctor did not consider himself one of them. He condemned the Nazis and Fascists but he did not condemn the Communists until he saw them in action. In his writings, "Laisvoji mintis" (The Free Mind) and "Naujoji Gadynė", (The New Era) he promoted democracy, love for the Fatherland, and he highly approved the Lithuanian Ethnic Association. These ideals were definitely not promoted by the Communists.

Since his childhood days Dr. J. Šliūpas had desired to be a writer, to enlighten the people, to share his knowledge with others. He began his journalistic contributions to the press in 1882 and continued to write through 58 years until 1940. He had a wide variety of topics ranging from family life, to history, to politics and religion, to national needs and morals, to health questions, to literature and biographies, to Lithuania's past and hopes for the future.

When leaving Lithuania in 1883 Šliūpas had planned to return when independence was attained, so sure was he it would happen. For many years he sacrificed, worked, and struggled, and endured opposition and hostility. In his numerous writings and lectures he encouraged Lithuanians to prepare to be worthy leaders for their emerging nation.

As a practicing physician Dr. Jonas Šliūpas lived with his family on North Main Avenue in Scranton, Pennsylvania, before the outbreak of World War I.

On April 26, 1917, after the February Revolution he traveled to San Francisco, sailed over the Pacific, then by train across Siberia he reached Stockholm, the capital of Sweden on the Baltic Sea. There, as the only Lithuanian American, he attended the October Conference of Lithuanian leaders who met to formulate the February 16th Declaration of Independence.

To them he pledged the loyalty and support of Lithuanians in the United States.

While in Sweden he wasted no time to publicize Lithuania's approaching freedom. He compiled and published his former lectures in a book called, "Lithuanian Freedom," and "The Past, Present, and Future of Lithuania." In a book of 162 pages in Lithuanian he presented his ideal "The Lithuanian-Latvian Republic, and the Union of Northern Nations."

In the two books, one in English and the other in Lithuanian, Dr. J. Šliūpas explained how the variety of nations enriches human experience, stimulates creativity, and promotes progress. Small independent nations abhor the use of force and war. The ideal of continued peace and freedom was the desired goal.

Dr. Jonas Šliūpas noted that in the past the Lithuanians had shared their talents and intellectual aptitudes in many areas with the Poles, the Russians and Germans, and, I may add, Thaddeus Kosciuško whose father was Lithuanian had offered his knowledge and service for the success of the American Revolution. History affirms these truths.

Lithuanians also proved their political maturity. In the 1905 Revolution they were the only ones in Russia who sent representatives to their own capital to demand autonomy for their nation.

During World War I Dr. Jonas Šliūpas placed his hopes in the Allied Nations.

He was certain of their victory. Ten days after President Wilson's famous Fourteen Points presented to a joint session of Congress on January 8, 1918, a group of Lithuanian Catholics, meeting at the Information Bureau in Washington, expressed that the time had come for a General Convention to which the National Council agreed.

On March 13, 1918, representatives of the Catholic and National Councils met at Madison Square Garden in New York. The main agenda for complete independence for Lithuania included that it be guaranteed by the Peace Conference with participation of Lithuanian representatives. Among other statements it declared Lithuanians would not tolerate any political or economic ties with other nations.

The National and Catholic Organizations formed a common Executive Committee whose members were to reside in Washington. Tomas Norus-Naruševičius was elected chairman, Rev. J. Žilius was secretary, Dr. J. Šliūpas was among the ten participants. The Lithuanian Information Bureau was to be called "The Lithuanian National Council and Information Bureau."

In May Dr. Šliūpas returned to Washington to confirm the de jure recognition of independence for Lithuania. He also initiated a diplomatic struggle with the Poles which lasted throughout Lithuania's independent existence.

Eventually Lithuania's delegates were entitled the privilege to receive an audience with the president apart from the Poles.

A characteristic act of the doctor was his response to the speech of Senator Henry Cabot Lodge delivered August 23, 1918. It presented the goal of the United States to make the post-war world safe for democracy. In a memorandum presented to the Senator, Dr. Šliūpas requested assured independence for Lithuania and Latvia. The memorandum was included in the Congressional Records August 29,1918. It is a continuing witness of the doctor's involvement with the Legislative Branch of the United States government.

The opportunity for a position in Lithuania's central government had not been extended to Dr. Šliūpas. From 1922 to 1941 he felt as though an invisible hand kept these positions away from him. This, however, did not prevent him from renewing his efforts to raise social, economic, and intellectual suggestions for the nation's advancement.

When President Smetona inferred that the doctor wanted to start a revolution, Dr. Šliūpas assured him all he wanted was reform and justice in the nation, not homicide. He was pleased with improvements in the field of education, the promotion of farming, trade and industry. He looked forward to the day when the people would take their rightful places in their own nation.

He knew the people valued his work for the public welfare. He was chosen an honorary member of the physicians organization, "Filii Lithuaniae". The University of Vytautas the Great bestowed on him "honoris causa" a Doctorate of Medicine, of Law, and of History. The Latvian government presented him with the Order of Three Stars. The Lithuanian government offered him the first and second degrees of the Order of Gediminas.

Dr. Šliūpas saw this as approval of his efforts to guide an organized nation to freedom and self-esteem, to the practice of ethnical and moral values. He was among the first to look upon women as equal to men. Jonas recalled his beloved mother's dedication to her home and family, and the hardships she heroically endured. His love for her reached out in respect for all womenkind. Respect is the offspring of love.

He encouraged the people to landscape their cemeteries so that the places of rest for their loved ones and friends would reflect esteem for those who once lived upon this earth. He referred to the Scandinavian cemeteries as models for Lithuanians to copy. They had flower-beds, shrubs and monuments, and pictures of the deceased.

With benches for the living their cemeteries were places for reflection and meditation, not areas for grief and mourning. They were meant to be sources for inspiration to work for the good of others, for one's own nation and for the world, before time ran out.

When Dr. J. Šliūpas was head of the Šiauliai branch of the Bank of Trade and Industry he had many dealings with the people. He listened to their complaints, offered advice, and proved himself a man of experience and a respected authority. He was sociable and friendly to all who came to him.

After trial and sorrow entered his life with the death of his wife, Liudmila, and the Bank of Trade and Industry failed, he met Grasilda Grauslytė in Palanga, the Lithuanian Atlantic City. While there, the clouds of his life lifted and the sun rose again.

Dr. J. Šliūpas and Grasilda Grauslytė were married in 1929. After settling in Palanga, their son, Vytautas, was born to them October 24, 1930. Because the doctor's reputation as a public activist for Lithuania's welfare preceded him, he was elected mayor of the resort city.

During a scout gathering in Palanga in 1933, Dr. Jonas Šliūpas as mayor was host to the British founder of Boy Scouts, Lord Baden Powell. A seasoned veteran and versatile in English, Šliūpas served as interpreter for President Antanas Smetona. Then, having prepared a fitting reception for the guest, he presented him with the key to the city and named a street in his honor.

A Lithuanian historian, Dr. Juozas Jakštas, in his book about the life and accomplishments of Dr. Šliūpas, referred to him as a radical. According to Webster the word is derived from radix, radicis, meaning a root. It is defined as "going to the center, the foundation or source." Lithuanians, before their Christianization worshipped nature in the sun, in thunder the sturdy oak tree, and other manifestations. They regarded living creatures with awe and respect. They lived in peace and let others live.

Dr. Šliūpas blamed much of Lithuania's woes, the loss of land, the enslavement of her people, the attempted annihilation of her language and culture, on those who came in the name of Christianity. The Teutonic Knights brought the sword, the Poles imposed polonization, the Russians came with Orthodoxy and russification.

In his unsatiable thirst for knowledge Dr. Šliūpas had read L. Buchner's writings which led him to the liberal path of a free-thinker. To Draper he contributed, quote "his rescue from the snares of Catholic enslavement." For the continued spread of liberal thinking in Lithuania he made use of the writings of R.B. Ingersoll, an American agnostic. Through an organization centered in Kaunas and branched out into 140 chapters, he hoped to reach the masses through periodic publications of "Laisvoji Mintis," but the Lithuanian public, unreceptive to alienation from their Catholic faith, were not interested.

However, at a celebration extended to him for his 75th birthday, Dr. Šliūpas was thanked for his accomplishments for the nation and was numbered among the first contenders for human rights and freedom. In the years following the difficult time of cruel suppression, when the name of Lithuania was erased from the map of the world and her people were reduced to slaves without rights, Dr. J. Šliūpas was among the first to enlist in the difficult and unequal struggle for Lithuania's liberation and re-birth.

The birthday celebration which he remembered for some time, was described by Dr. Šliūpas himself. Before referring to the greetings and words of acclamation delivered by the speakers, he remarked, quote: "What would the Socialists, the clergy, and the polonizers say on hearing that the Lithuanian people prepared for me such a Birthday celebration that very few people live to see." (p. 252) Among the speakers were such officials as the rector of the University in Kaunas, and the Minister of Education, besides 17 others representing a variety of organizations and localities. He and his family were presented with round-trip tickets to the United States. The Brooklyn tailors, Drobės Cooperative, had sent greetings along with an invitation to come to their headquarters to be measured for a suit and overcoat.

Dr. Šliūpas, with his wife and son, made use of the opportunity the following summer. After 15 years of absence he was able to meet his former friends and co-workers in the United States.

The mark of esteem extended to Dr. Šliūpas on his 75th birthday was the most elaborate and the last to be celebrated in Lithuania. His 80th birthday, which would have been marked in the spring of 1941, coincided with the first Bolshevik occupation. The day was passed in silence. He was not a "persona grata" for the Soviets.

With the Soviet arrival Dr. Šliūpas had been offered a government post which he refused. All his life he worked and fought for Lithuania's freedom. He found it impossible to join those who, with brute force, were prepared to quench its life. He became a private citizen in Palanga, a spectator of Lithuania's approaching agony.

During the second Soviet invasion with the departure of the Germans, Dr. J.

Šliūpas left Palanga and joined the wave of people leaving their country for the safety of their families. For a short time he lived in Vienna then travelled to a peaceful town in Austria near the Switzerland border. While there he was asked, on November 1st, 1944, to travel to Berlin to join others who would come to record a message to be broadcast over the air waves to American Lithuanians.

Dr. J. Šliūpas, feeling capable of enduring the strains and dangers of a journey during wartime, had not counted on freezing on a train with shattered windows, being awakened from sleep to descend to a bomb-shelter in a hotel, spending time in an unheated room, and attending meetings with Lithuanian leaders for two days. On the day of departure from Berlin, he retired at one in the morning, but could not sleep because of severe chest pains. At 8 o'clock that morning a doctor, summoned to his bedside, arrived at 9 but found that Dr. J. Šliūpas had died. It was November 6, 1944.

Upon hearing of his death, Lithuanians in the area and from afar, under dangerous circumstances of intermittent bombing, came to convey their respects. The inscriptions on the wreaths and bouquets of flowers revealed the sentiments of the people; "To the Founder of Lithuania's Re-birth", "To a Great Lithuanian Patriot" "To an Aušrininkas (Dawn-movement Leader)", "To Dr. J. Šliūpas, Lithuania's Patriarch."

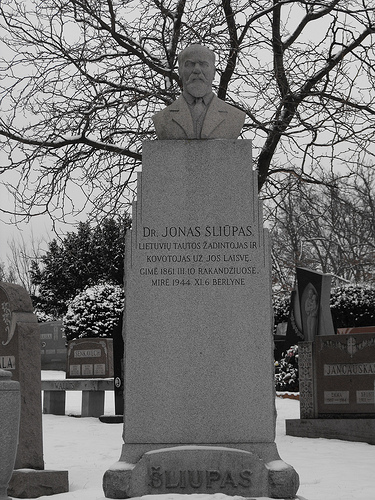

The ashes of Dr. Jonas Šliūpas, kept in an urn, were brought to the United States by his wife and son in 1947 and buried in the National Cemetery in Chicago. At the place of burial near the main road in the very center of the cemetery, a monument was raised in his memory.

Today the monument speaks to generations of America's Lithuanians of a devoted Patriot who roused their forefathers in the United States and in Lithuania to reclaim their freedom and identity. Dr. Jonas Šliūpas pressed an indelible responsibility on the consciousness of true Lithuanians to value their great past and to build upon it for a worthy future.

The monument with the urn in the National Cemetery in Chicago is a visible expression of one man's efforts to rekindle the flame of love for one's own nation, to seek freedom for self-expression and rights as a people.

On a stone monument in the Lithuanian National Cemetery in Chicago are the words in Lithuanian:

DR. JONAS ŠLIŪPAS

the rouser of the Lithuanian nation,

contender for her freedom,

born March 4, 1861, in Rakandžiai,

died November 6, 1944, in Berlin.

To be a champion of patriotism and a contender for freedom are two worthy goals for attainment. To persevere to the end in any worthy endeavor requires courage, strength of character, and ability to keep the vision alive in spite of confliciting and discouraging circumstances.

Any champion or contender, irrespective of the goal, must expect and withstand opposition, hostility, verbal abuse, character assassination, slander and prejudice. In a word, it requires exceptional heroism. All this and more Dr. Jonas Šliūpas faced in his life, both in Lithuania and in the United States. Motivated by pity and love for an enslaved people he paid a very high price, spending his entire life for a cause in which he strongly and passionately believed.

To Dr. J. Šliūpas the enemies and exploiters of Lithuanians were the polonized clergy. He felt it was his duty to do everything in his power to defend the unsuspecting people from being deprived of their ethnic and work capacity, knowing he could not wage a successful battle by himself, he turned to unbelievers and enemies of the Church for assistance. It was his dependence on them that earned for Šliūpas the name of atheist.

This label served the polonized clergy as a convienient scare device to keep the Lithuanians from leaving the Poles until Rev. Alexander Burba of Plymouth, Pennsylvania, proved them wrong. Since Catholic means "universal"

it was possible to be a Lithuanian Roman Catholic without being Polish. God requires no one to deny his identity t6 be numbered among His people.

Most Lithuanians did not know, — especially those living in Northeastern Pennsylvania, — that it was the most important goal of Dr. J. Šliūpas to keep alive their ethnic identity through education and enlightenment, that they learn about their great past as a people, and build upon this past into the future. Least of all did he wish to make them atheists. Lithuanians as pagans believed in higher beings and in life after death. All of nature was a reason for awe and worship.

* From "Dr. Jonas Šliūpas" by J. Jakštas.

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

VilNews e-magazine is published in Vilnius, Lithuania. Editor-in-Chief: Mr. Aage Myhre. Inquires to the editors: editor@VilNews.com.

Code of Ethics: See Section 2 – about VilNews. VilNews is not responsible for content on external links/web pages.

HOW TO ADVERTISE IN VILNEWS.

All content is copyrighted © 2011. UAB ‘VilNews’.

Click on the buttons to open and read each of VilNews' 18 sub-sections

Click on the buttons to open and read each of VilNews' 18 sub-sections

[…] also our VilNews article https://vilnews.com/?p=3545, “The man who declined the […]

[…] 9. Lithuania declared independence in 1918, after 123 years of mostly Russian occupation. The interwar years were very successful and the country prospered immensely. Kaunas was the capital for the period 1919-1940, after Poland occupied Vilnius and southern Lithuania. https://vilnews.com/?p=3545 […]

[…] “Now the next day, that followed the day of the preparation, the chief priests and Pharisees came together unto Pilate, Saying, Sir, we remember that that deceiver said, while he was yet alive, After three days I will rise again. Command therefore that the sepulchre be made sure until the third day, lest his disciples come by night, and steal him away, and say unto the people, He is risen from the dead: so the last error shall be worse than the Additionally you can check out: https://vilnews.com/?p=3545 […]

[…] Recently, Ugg boots are gaining worldwide popularity. There are millions Also you can read this related blog page: http://armanisuitsformen.topcheapmart.com/how-to-buy-mens-minnetonka-moccasins/ Further you can see this related post: http://mensslippers.topcheapmart.com/where-to-buy-ugg-boots-to-guarantee-authenticity/ In addition you can check out this related post: https://vilnews.com/?p=3545 […]