THE VOICE OF INTERNATIONAL LITHUANIA

|

VilNews has its own Google archive! Type a word in the above search box to find any article.

You can also follow us on Facebook. We have two different pages. Click to open and join.

|

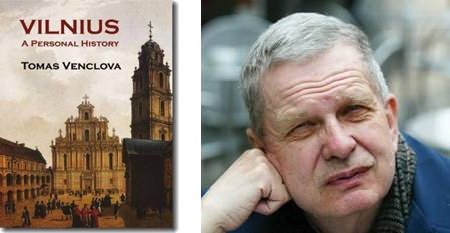

The history of the amazing Lithuanian city written by the great poet most qualified to write about it. This book includes a dialogue between the author and Nobel Prize laureate Czeslaw Milosz about the city. An absolutely indispensable work on the city that produced John Gielgud, Bernard Berenson and the Budapest String Quartet.

This is the third in a series of excerpts from Tomas Venclova’s book “Vilnius a Personal History”:

PAGAN LITHUANIA

In world history, the year 1323 does not stand out in any way, but it is worth remembering that this was the period when the Renaissance was beginning in Europe: Dante had been dead for two years; Petrarch was just nineteen years old; and Giotto was fifty-six. (He had already painted the frescoes in Padua and Assisi.) That same year, Count Orgaz died in Spain. According to tradition, two saints assisted in a wondrous manner at his funeral ― much later this became the subject of one of El Greco’s most famous paintings. At the same time Vilnius was being founded, another famous heathen capital was established at the other end of the world: Mexico’s Tenochtitlan, only to be destroyed two hundred years later by Spanish conquistadors.

In the Europe of that time, Lithuania was an amazing exception. Similar states had existed about a thousand years before, at the time of the great migration of peoples, but they fell into oblivion. The neighboring peoples ― the East Slavs and Poles ― had long worshipped Jesus Christ, even though they had different dogmas, liturgies, and church languages. Christianity had been forced on the Old Prussians and Letts by the Teutonic Knights. In contrast, the Lithuanians were the only ones on the continent who held on to their original faith, and the battles with the Knights only strengthened them in their determination. What’s more, they annexed Christian peoples to their state, just as the Franks and the old Anglo-Saxons had once done. They did not destroy the local Christian holy places, but treated them with respect.

What was this old belief like? The nineteenth-century Romantics, including Mickiewicz, spoke of a veritable Lithuanian pantheon and tried to reconstruct it from the few ancient reports that were available. Teodor Narbutt stands out among these Romantics. He produced a nine-volume Lithuanian history, the first volume devoted exclusively to mythology. The gods mentioned by him correspond to the gods of Olympus and, less frequently, to those of the Edda. Narbutt collected statuettes and heathen Lithuanian documents, all of which have turned out to be forgeries. Somewhat more credible is a sixteenth-century enumeration of gods that brings their number to five hundred. From this it is clear that the Lithuanians did not have a pantheon like those in the works of Homer and Virgil, but that they worshipped whatever they encountered: especially trees and fire, but also rivers, stones, birds, bees, and even household items. There were spirits concealed in everything: usually they were small, funny demons; and, less often, more powerful beings. The most powerful was Perkūnas, the god of thunder, who fought against Velinas, the embodiment of water and original chaos. Mythologists are trying to find a connection between Velinas and the Indian Varuna, and missionaries did use his name for the Christian spirit of evil who is today called velnias (“devil”) in Lithuanian. The first book in the Lithuanian language, a Protestant catechism, says that some of the heathens pray to Perkūnas; others to Laukosargas, protector of grain; and still others to Žemėpatis, who takes care of cattle. Those who subscribe to evil magic call on Kaukai and Aitvarai for help; the names of these two not particularly dangerous demons turn up in fairy tales to this day.

We know that the Lithuanians sacrificed animals and sometimes also human beings. It was quite common to burn high-ranking prisoners at the stake. Moreover, the corpses of their own people, together with their horses, falcons, and dogs were also burned, and the claws of wild animals were thrown into the funeral pyre so that the deceased would have an easier time climbing the hill. Apparently Gediminas, who remained unbaptized to the end, was also cremated in this manner in the Šventaragis Valley. The priests were called vaidila: some Lithuanian patriots claim that Wojtyła, the Polish family name of Pope John Paul II, derives from this word. Historians of old report that snakes were considered sacred, probably because they were seen as representatives of the underworld―the world of the dead, and of rebirth. The Lithuanians kept them in their houses and gave them milk, a custom that was retained in the Vilnius area up to and into the twentieth century. To kill a snake was to violate a taboo. The Soviets annulled that taboo for good, as well as many more significant ones.

Apparently, there really was a pagan sanctuary at the foot of the hill in Vilnius, but presumably it was the only one in the entire country. It is said that all the churches of Vilnius were erected on pagan places of worship. Milda, the goddess of love, was supposedly worshipped where the baroque Church of SS. Peter and Paul stands today, and Ragutis, the god of drinking―a Lithuanian Dionysus―was once honored where the Orthodox Pjatnitskaja Church is located. But this is just speculation by Narbutt and other Romantics. Still, the city of Gediminas―in those early times when its houses were still built of wood and in many places of brushwood and clay―apparently had not only one or more castles, but also numerous sacred places: springs and groves that were considered holy sites. The first Christian missionary to visit these lands, St. Adalbert, was put to death because he carelessly entered one such grove. In Vilnius, Catholics and Orthodox Christians still honor other martyrs who were killed by the heathens; but these are probably just pious legends. Christians had no reason to be alarmed in the heathen city. In his letters, Gediminas writes that there are Franciscan and Dominican churches in Vilnius in which they could pray to their God. One of these churches is still standing, although it has been rebuilt many times. It is St. Nicholas, located in a remote corner of the Old City, an example of a primitive, cozy Gothic style, with a rhythmic gable that delights the onlooker with its calm and stillness. As you step inside and stand under the low, star-studded, vaulted ceiling, you feel as though you were in a box or a cabinet. The church is first mentioned in the era of Gediminas’s grandsons; even then, it was built of stone and considered to be ancient.

It is entirely possible that a more complex pagan cult was created during Gediminas’s time to sanction his unusual State. Surrounded as it was by Christianity, this cult would have had no chance of survival. The rulers themselves leaned toward Orthodox Christianity, which offered a tempting opportunity to unite the East Slavic territories under their scepter. Vilnius competed with Moscow. Algirdas, the son of Gediminas, launched three attacks against Moscow and even got as far as the Kremlin, but the Muscovites bought themselves off. At this point, the fate of Eastern Europe could have taken an unexpected turn: Moscow might have remained insignificant, and Vilnius could have taken its place in history. But we shall leave these alternative historical scenarios where they belong―in the sphere of speculation. Moscow won the historical struggle and became the city with the dubious reputation it has today. It also captured Vilnius several times. But in the days of Gediminas’s immediate successors, the map of Eastern Europe looked completely different from the one we know now. In Pushkin’s drama, Boris Godunov, one scene takes place “in a country inn on the Lithuanian border.” I once asked my Slavic Studies students to show me on a map where this inn was located. They all searched for it along the present-day Lithuanian border, that is to say some twenty miles from Vilnius. Actually, it was just seventy miles from Moscow.

The era of a powerful pagan Lithuania impressed not only the Romantics. It also became the most important myth of Lithuanian nationalism. The intellectuals who set the philological revolution in motion by reviving Lithuanian and making it the official state language early in the twentieth century liked to claim that paganism was an almost perfect belief―tolerant and related to the old Indian Vedas. This profoundly pagan worldview was supposedly destroyed by narrow-minded Christian fanatics and replaced by nothing good. Such views cropped up again shortly before the collapse of Soviet power. Young people at Vilnius University, or associated with it, founded the “Romuva” Society. The name referred to medieval chronicles in which the most important Lithuanian shrine was called “Romuva”―a name invented by the chroniclers presumably to counterbalance Rome. Officially, the Communist rulers opposed the Romuva Society, but they secretly supported it because of its opposition to the Catholic Church, which had caused the Communists a great deal of inconvenience. The members of Romuva celebrated pagan festivals, baptized infants by annointing their heads with lake water, and spoke publicly of the heritage of the ancient Aryans, who had risen to be superior to the Slavs and other peoples.

It is hardly necessary to mention what unpleasant memories this triggers. The Romuva Society still exists today; it has even elected a high priest and built sacrificial altars on a couple of Vilnius’s hills. Occasionally, it reports sensational finds when the presumed relics of a shrine are dug up once again in somebody’s backyard. After the restoration of Lithuanian independence, a few members of Parliament proposed that the same rights be extended to Paganism ―“the Old Worship” they called it ― as are accorded to the other traditional religions. A poet I know explained to me that Lithuania should do what Japan has done: if people in Japan can pray in Shinto houses of worship and at the same time consider themselves Buddhists, then Lithuanians can be Pagans and at the same time Catholics. So far, little has come of such proposals. It is interesting of course that of all European capitals north of Athens and Rome, Vilnius is the only one in which there is a stratum of heathen memories―but this artificial heathenism is a curiosity, and most people realize that it in no way resembles the old forms of belief. There doesn’t seem to be any real depth to the chaos of the Lithuanian pagans; they weren’t bad warriors, but they didn’t have the stone churches, the icons, or the literature and church music their Christian neighbors could take pride in. Nevertheless, Algirdas Brazauskas, the first president of a once-again independent Lithuania, was inaugurated twice: first in Gediminas’s Castle with a heathen ritual the patriots had invented, and the second time in a Catholic ceremony at the Cathedral. Today, the presidential inauguration ceremony no longer features such neo-pagan pageants.

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

VilNews e-magazine is published in Vilnius, Lithuania. Editor-in-Chief: Mr. Aage Myhre. Inquires to the editors: editor@VilNews.com.

Code of Ethics: See Section 2 – about VilNews. VilNews is not responsible for content on external links/web pages.

HOW TO ADVERTISE IN VILNEWS.

All content is copyrighted © 2011. UAB ‘VilNews’.

Click on the buttons to open and read each of VilNews' 18 sub-sections

Click on the buttons to open and read each of VilNews' 18 sub-sections

[…] Read more… Category : Front page […]