THE VOICE OF INTERNATIONAL LITHUANIA

|

VilNews has its own Google archive! Type a word in the above search box to find any article.

You can also follow us on Facebook. We have two different pages. Click to open and join.

|

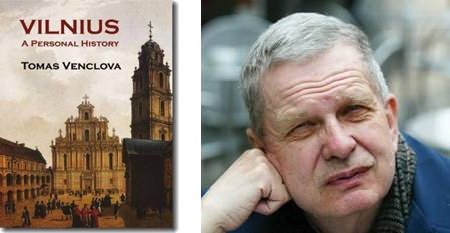

The history of the amazing Lithuanian city written by the great poet most qualified to write about it. This book includes a dialogue between the author and Nobel Prize laureate Czeslaw Milosz about the city. An absolutely indispensable work on the city that produced John Gielgud, Bernard Berenson and the Budapest String Quartet.

This is the fourth in a series of excerpts from Tomas Venclova’s book “Vilnius a Personal History”:

TODAY: Lithuanians,

“The Saracens of the North”

Saracen was a term used by the ancient Romans to refer to a people who lived in desert areas in and around the Roman province of Arabia, and who were distinguished from Arabs.

The Order of Teutonic Knights and all of Europe called the Lithuanians, “the Saracens of the North.” Established at the time of the Crusades in Palestine, the Order was responsible for fighting the war against the Moslems, but the Knights soon had to be shifted to the Baltic coast. To the Order’s zealous members, Lithuania represented the menacing “Other,” an empire of barbarism, of primeval darkness: Europe’s subconscious that had to be enlightened, controlled, and punished. The Lithuanians, on the other hand, considered the Knights of the Order as a no-less-menacing “Other.” What the Knights saw as heroic deeds, the Lithuanians considered brazen robbery and murder―and vice versa. There have not been many conflicts in Europe of comparable length and tenacity as the war between the two powers, which lasted some two hundred years. The Knights founded Thorn, Marienburg, Königsberg, and numerous other castles ― but they did not get farther than the Neman River (in Lithuanian: Nemunas). Gediminas, according to tradition, is said to have died in battle at the Neman; his ashes were buried on the hill next to the Vilnius Castle. Another branch of the Teutonic Order governed Riga and Tallinn, but they too were brought to a standstill north of the Lithuanian territory, where the Lithuanian-Latvian border is today.

The first time I went to Vienna, I wanted above all to visit the church that to this day belongs to the Order of the Teutonic Knights. Situated in the center of the city, it is very modest. A member of the Order, a peaceful-looking old man smoking a pipe, acted as my guide. He took me through the small church museum and showed me documents of the Order and maps of old Lithuania and its neighboring lands. I was the sole visitor, probably the only one that day. It may sound ridiculous, but I felt somewhat triumphant: practically nothing is left of the Order besides this church and its little museum, while my country, which was attacked by the Knights and which they wanted to destroy, still endures. The way I felt reflects how deeply rooted the history of this war is in Lithuanian consciousness. The Romantics found in this an inexhaustible source of inspiration, as Byron found in the Orient. The most popular theme is the story of Grandmaster Konrad von Wallenrode, who unsuccessfully marched against Vilnius, was disliked by his subordinates, and died young. Mickiewicz wrote a poem about him: it is full of unexpected twists and turns, almost like a spy novel, and it gradually becomes clear that Wallenrode was actually a Lithuanian who had infiltrated the upper level of the Order so that he could destroy it from within. Of course this is pure fantasy, but the name Wallenrode has become a symbol in Lithuania and Poland: quite a few Nazi and Communist collaborators have tried to justify themselves, both privately and publicly, saying that they acted in the interest of their own people, as he did. Another figure who has found his way into world literature conspired with Wallenrode: Henry Bolingbroke, the future King Henry IV of England, founder of the dynasty of the Red Rose and hero of the eponymous play by Shakespeare. In 1390, Henry Bolingbroke, with three hundred Englishmen and Wallenrode’s knights, briefly occupied Vilnius. According to Bolingbroke, the city was built of wood at that time and had no protective walls, but in fact it already had a large stone castle. The attackers set the city and a smaller castle on fire, but they could not capture the large one.

Toward the end of the fourteenth century, this war became hopeless for Lithuania. It reminds me of the recent war in Chechnya; the hatred on both sides and the extent of the destruction are comparable. The descendants of Gediminas tried to find allies. After several futile attempts, they realized they would have to convert to Christianity in order to deprive the Knights of their most important argument. I do not think that dogmatic fine points were important to the Lithuanians; but the Orthodox Faith, that is to say, the Eastern Heresy, was a dubious defense against the Teutonic Knights. On the other hand, being forced to accept Christianity by the Teutonic Order would have meant capitulation and the collapse of the state. It was at this point that Poland came to their aid, having some accounts of its own to settle with the Knights. It was suggested that the grandson of Gediminas, Jogaila (Jagiełło), marry the thirteen-year-old Polish Princess Jadwiga (Hedwig), who had lost her father; that he have himself baptized; and that he become the ruler of both countries. Jogaila agreed. For him, this was not a romantic union but a political calculation. However, Jadwiga resisted. She loved the son of an Austrian duke, but even more importantly, she was afraid of the thirty-year-old Lithuanian barbarian. It is said that she sent a trusted nobleman to Vilnius who was to report to her what he found out about the prince of that wild land. The emissary went to a banquet feast with Jogaila, was even said to have joined him in a sauna, and let Jadwiga know that she had nothing to fear. Nonetheless, the marriage was not a happy one; Jadwiga died soon afterward, leaving no heirs. Jogaila married three more times. Finally, at an advanced age, he had children with his fourth wife, thus founding the renowned Jagiellon Dynasty. Supposedly, all European ruling families have the blood of Jogaila and Gediminas in their veins.

Jogaila accepted the Polish crown, ordered the destruction of the pagan sanctuary in Vilnius, extinguished the sacrificial fires, killed the sacred snakes, and on the same spot erected a new cathedral that was even larger than Mindaugas’s. He and his cousin Vytautas baptized the heathen subjects, pushing them into the river in droves and giving the whole lot the same Catholic name. It is said that the two rulers even translated the Lord’s Prayer, the Ave Maria, and the Credo into Lithuanian. Jogaila moved to Krakow, the Polish capital, leaving Vilnius and its castles to Vytautas. The united Lithuanians and Poles together resisted the Teutonic Order, and, in their decisive victory at the Battle of Grunwald (1410), they managed to remove the Order from the political equation once and for all. The defeated Order, as we know, became a museum piece. But it has preserved its place in the sphere of myth. The Knights of the Order continue to symbolize the fatal danger emanating from the West, a phantasm that always appears ― or is artificially conjured up ― whenever the political situation warrants. During the First World War, the army of Kaiser Wilhelm was compared to the Teutonic Knights, even by the Germans themselves. And during the Second World War, the rulers of the Soviet Union, using the same symbolism, were partially successful in their attempts to manipulate public opinion. Somewhat later, Lithuanian newspapers printed a photograph of Konrad Adenauer wearing the cloak of the Order (he was in fact a member of the Knights); but most Lithuanians ignored it, as they did almost all Soviet propaganda. The Adenauer photo may finally have destroyed the myth. In any case, Lithuanian opponents of European Union membership did not seek recourse in it to support their position.

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

VilNews e-magazine is published in Vilnius, Lithuania. Editor-in-Chief: Mr. Aage Myhre. Inquires to the editors: editor@VilNews.com.

Code of Ethics: See Section 2 – about VilNews. VilNews is not responsible for content on external links/web pages.

HOW TO ADVERTISE IN VILNEWS.

All content is copyrighted © 2011. UAB ‘VilNews’.

Click on the buttons to open and read each of VilNews' 18 sub-sections

Click on the buttons to open and read each of VilNews' 18 sub-sections

[…] Read more… Category : Front page […]