THE VOICE OF INTERNATIONAL LITHUANIA

|

VilNews has its own Google archive! Type a word in the above search box to find any article.

You can also follow us on Facebook. We have two different pages. Click to open and join.

|

![]()

EUROPE – MY HOME & MY CASTLE (8 of 10)

From east to west

in European Russia

|

VilNews is on its way around Europe!

Our today's journey begins at the Ural River between Asia and Europe, where Tour guide: Aage Myhre

|

To Siberia – probably the only one ever going there voluntary, without a visa

|

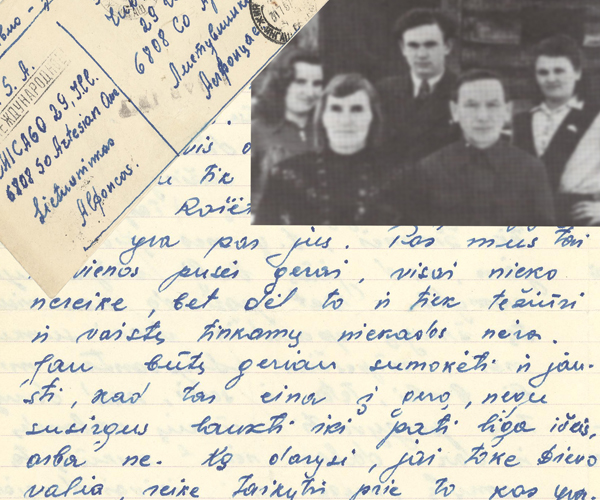

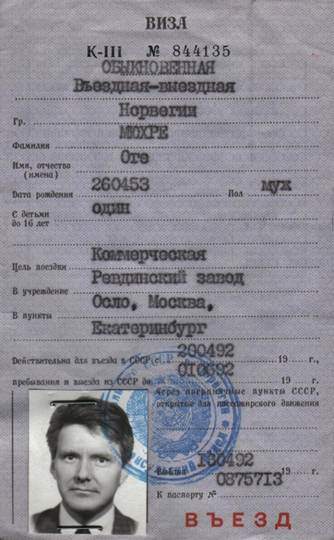

It’s January 1992. I have been invited on a trip to Orenburg city on the border to Siberia. Together with two British business leaders that I early in the 1990s helped with contacts in Russia. As a Norwegian I cannot be issued a visa to Russia in Vilnius. But according to the Lithuanians, I can safely travel to Siberia without papers. Soviet rules are still valid. Lithuania and Siberia are both considered to be just regions, six months after the termination of the USSR. Orenburg Oblast is home to Orenburg Cossacks at the Ural River, considered the boundary between Europe and Asia... |

|

I decide to take the chance. Not long after we land in Moscow. Flights from Vilnius still belong to the category domestic, despite the months that have now passed since Lithuania was officially approved as an independent nation, also by Russia. Therefore, no passport control, neither in Vilnius nor on arrival Moscow. The very long journey around the metropolis, to the other airport, the one that operates flights to the east of Russia, is also fine. Not long after we are smoothly seated in a Yak-42 from the airline Aeroflot. This is a flight I will never forget. There is no food on board, so many of the passengers sit in the aisle to eat food brought along. Not to forget the drinks. The only thing missing is someone lighting a bonfire for cooking or frying food. Passengers have distinctive facial characteristics. Asian. Mongolian. The vodka they generously share with us is very handy in reducing anxiety for what might happen with this incredibly smelly plane...

|

|

|

|

|

We land in winter dressed Orenburg a late, dark January evening. Two meters of snow. Cold of course. We are picked up by our hosts. One car in front, one behind, we in the middle. There is much here in the Russian wilderness that is about security and protection these days. The dacha, the house, which awaits us there, deep in the Ural forests, is brightly lit, surrounded by high barbed wire fences. German Shepherd Dogs barking persistently. I feel uncomfortable. This give me associations to a concentration camp, to Stalin prisons camps further east, on Siberia's frozen tundra. The Gulags.

Inside the house two lightly clad ladies are waiting in the lavishly decorated dacha that soon proves to be a small luxury hotel. Facial expressions of the young ladies are indescribable in what they see that I have brought with me my wife. But the food is good. The same is the cognac and whisky, all 'blue label'.

"Only one western delegation has visited the city before you, namely Swedish Volvo," tells our host. This is a fact that has made them nervous about our safety. They say that a whole army stood around the runway when we landed. All with sharp loaded Kalashnikov machine guns, ready to protect us. Just in case ... Over the next few days we visit the city's mayor and discuss possible business with the hosts. A total abundance of food and fine beverages always available...

The flight back to Moscow takes place during daytime, in sparkling sun over the endless snow-covered plains and forests west of the Urals. Soon we arrive in Moscow. We check in at the Hotel Metropol right on Red Square. Luxury for $500 per night. But it feels good after the trip to the Siberian gateway. No one checks my papers.

Moscow is enormous – but a city I do not easily become familiar with

About 10 million people live in Moscow. It makes the city to number seven in the world, largest in Europe.

Moscow is enormous. Everything is big here. Inhuman. The outskirts are characterized by gloomy gray block houses from the Soviet era, while the city centre has many historic and newer buildings that really deserve closer acquaintance. I have tried several times, but there is something about Moscow as a whole that I never feel comfortable with. The greyness. Doldrums. New rich oligarchs in expensive luxury cars, while the majority are living in rather poor conditions. The often harsh atmosphere of business at any cost. Culture The country Russia drowns in greed, corruption and fraud. Terribly sad, because Russia has so many good aspect and qualities to be proud of.

Moscow is the city with 'rush hour' round the clock. "Russia has two problems: fools and roads", said author Nikolai Gogol nearly two centuries ago. The Russians have a tendency to protest by saying that there are fools all around the world, but when it comes to roads they agree. Today's traffic is Russia's Achilles heel, a disaster that seems to have no salvation.

Moscow's endless traffic jams have become the icon that defines the Russian capital. More than the Lenin Mausoleum, the prostitute on Leningradskoe Shosse, and unregistered taxi drivers from various Stan Republics offering services from their abandoned car wrecks.

Kremlin and the Red Square in Moscow.

Photo: Wikipedia.

|

|

History of Russia |

Russia, officially known as both Russia and the Russian Federation, is a country in northern Eurasia. It is a federal semi-presidential republic, comprising 83 federal subjects. From northwest to southeast, Russia shares borders with Norway, Finland, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania and Poland (both via Kaliningrad Oblast), Belarus, Ukraine, Georgia, Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, China, Mongolia, and North Korea. It also has maritime borders with Japan by the Sea of Okhotsk, and the United States by the Bering Strait.

At 17,075,400 square kilometres (6,592,800 sq mi), Russia is the largest country in the world, covering more than one eighth of the Earth's inhabited land area. Russia is also the eighth most populous nation with 143 million people. It extends across the whole of northern Asia and 40% of Europe, spanning nine time zones and incorporating a wide range of environments and landforms.

A Viking was the first Russian ruler

The history of Russia begins with that of the Eastern Slavs and the Finno-Ugric peoples. The state of Garðaríki ("the realm of towns"), which was centered in Novgorod and included the entire areas inhabited by Ilmen Slavs, Veps and Votes, was established by the Varangian chieftain Rurik in 862 (the traditional beginning of Russian history).

Scandinavian Norsemen, called "Vikings" in Western Europe and "Varangians" in the East, combined piracy and trade in their roamings over much of Northern Europe. In the mid-9th century, they began to venture along the waterways from the eastern Baltic to the Black and Caspian Seas. According to the earliest Russian chronicle Rurik was elected ruler before his successors moved south and extended their authority to Kiev, which had been previously dominated by the Khazars.

Thus, the first East Slavic state, Kievan Rus', emerged in the 9th century along the Dnieper River valley. A coordinated group of princely states with a common interest in maintaining trade along the river routes, Kievan Rus' controlled the trade route for furs, wax, and slaves between Scandinavia and the Byzantine Empire along the Volkhov and Dnieper Rivers

Kievan Rus', the first united East Slavic state, was founded by Rurik's successor Oleg of Novgorod in 882. The state adopted Christianity from the Byzantine Empire in 988, beginning the synthesis of Byzantine and Slavic cultures that defined Russian culture for the next millennium. Kievan Rus' ultimately disintegrated as a state because of the Mongol invasion of Rus' in 1237–1240.

Two tsars competing with the Grand Duchy of Lithuania

During that time a number of regional magnates, in particular Novgorod and Pskov, fought to inherit the cultural and political legacy of Kievan Rus'. After the 13th century, Moscow came to dominate the former cultural center. In the 15th century, the grand princes of Moscow went on gathering Russian lands to increase the population and wealth under their rule. The most successful practitioner of this process was Ivan III (the Great) who laid the foundations for a Russian national state. Ivan competed with his powerful northwestern rival, the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, for control over some of the semi-independent Upper Principalities in the upper Dnieper and Oka River basins.

The development of the Tsar's autocratic powers reached a peak during the reign (1547–1584) of Ivan IV (the Terrible). He strengthened the position of the monarch to an unprecedented degree, as he ruthlessly subordinated the nobles to his will, exiling or executing many on the slightest provocation. Nevertheless, Ivan is often seen as a farsighted statesman who reformed Russia as he promulgated a new code of laws (Sudebnik of 1550), established the first Russian feudal representative body (Zemsky Sobor), curbed the influence of clergy, and introduced the local self-management in rural regions.

Although his long Livonian War for the control of the Baltic coast and the access to sea trade ultimately proved a costly failure, Ivan managed to annex the Khanates of Kazan, Astrakhan, and Siberia.

By the 18th century, the Grand Duchy of Moscow had become the huge Russian Empire, stretching from the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth eastward to the Pacific Ocean. Expansion in the western direction sharpened Russia's awareness of its separation from much of the rest of Europe and shattered the isolation in which the initial stages of expansion had occurred. Successive regimes of the 19th century responded to such pressures with a combination of halfhearted reform and repression. Russian serfdom was abolished in 1861, but its abolition was achieved on terms unfavorable to the peasants and served to increase revolutionary pressures. Between the abolition of serfdom and the beginning of World War I in 1914, the Stolypin reforms, the constitution of 1906 and State Duma introduced notable changes to the economy and politics of Russia, but the tsars were still not willing to relinquish autocratic rule, or share their power.

The Russian revolution in 1917

The Russian Revolution in 1917 was triggered by a combination of economic breakdown, war weariness, and discontent with the autocratic system of government, and it first brought a coalition of liberals and moderate socialists to power, but their failed policies led to seizure of power by the Communist Bolsheviks on 25 October. Between 1922 and 1991, the history of Russia is essentially the history of the Soviet Union, effectively an ideologically based state which was roughly conterminous with the Russian Empire before the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk. The approach to the building of socialism, however, varied over different periods in Soviet history, from the mixed economy and diverse society and culture of the 1920s to the command economy and repressions of the Joseph Stalin era to the "era of stagnation" in the 1980s. From its first years, government in the Soviet Union was based on the one-party rule of the Communists, as the Bolsheviks called themselves, beginning in March 1918. However, by the late 1980s, with the weaknesses of its economic and political structures becoming acute, the Communist leaders embarked on major reforms, which led to the fall of the Soviet Union.

Following the Russian Revolution, Russia became the largest and leading constituent of the Soviet Union, the world's first constitutionally socialist state and a recognized superpower, which played a decisive role in the Allied victory in World War II. The Soviet era saw some of the most significant technological achievements of the 20th century, including the world's first human spaceflight. The Russian Federation was founded following the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991, but is recognized as the continuing legal personality of the Soviet state.

Today’s Russia

The history of the Russian Federation is brief, starting from the late 1991. Russia was recognized as the legal successor to the Soviet Union on the international stage. However, Russia has lost its superpower status as it faced serious challenges in its efforts to forge a new post-Soviet political and economic system. Scrapping the socialist central planning and state ownership of property of the Soviet era, Russia attempted to build an economy with elements of market capitalism, with often painful results. Even today Russia shares many continuities of political culture and social structure with its tsarist and Soviet past.

Russia has the world's 11th largest economy by nominal GDP or the 6th largest by purchasing power parity, with the 5th largest nominal military budget. It is one of the five recognized nuclear weapons states and possesses the largest stockpile of weapons of mass destruction. Russia is a great power and a permanent member of the United Nations Security Council, a member of the G8, G20, the Council of Europe, the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation, the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation, the Eurasian Economic Community, the Organisation for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE), the World Trade Organisation (WTO), and is the leading member of the Commonwealth of Independent States.

Russia has the world's largest reserves of mineral and energy resources and is the number one natural gas producer as well as number one oil producer globally. Russia has the world's largest forest reserves and its lakes contain approximately one-quarter of the world's fresh water.

Russian-Lithuanian relations

During the course of the 19th century, the Presidential Palace in Vilnius served as a residence for several Imperial Russian governors, such as Mikhail Muravyov, nicknamed "The Hangman". In 1812, both the Russian Tsar Alexander I and the French Emperor Napoleon Bonaparte used the Palace as their residence. During Napoleon's invasion of Russia, he organized military operations and Lithuanian army units from the Palace, including five regiments of infantry, four cavalry regiments, and the National Guard of Vilnius. He received Lithuanian noblemen, newly appointed officials of the administration, and other dignitaries in the Palace as well. After Napoleon's defeat in 1812, the Palace was used for ceremonial proposes; it was here that then-general Mikhail Kutuzov was awarded Russia's highest military award – the Order of St. George. During 1824-1834, the Palace was reconstructed by the prominent St. Petersburg architect Vasily Stasov in the Empire style, under supervision of Karol Podczaszyński. Stasov's reconstruction of the Palace has remained to this day.

During the Northern Wars (1655–1661), the Lithuanian territory and economy were devastated by the Swedish army. Before it could fully recover, Lithuania was ravaged during the Great Northern War (1700–1721). The war, plague, and famine caused the deaths of approximately 40% of the country's population.

Foreign powers, especially Russia, became dominant in the domestic politics of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth that had been established in 1569 (Union of Lublin). Numerous factions among the nobility used the Golden Liberties to prevent any reforms. Eventually, the Commonwealth was partitioned in 1772, 1792, and 1795 by the Russian Empire, Prussia, and Habsburg Austria.

The largest area of Lithuanian territory were occupied by the Russian Empire in 1795. After unsuccessful uprisings in 1831 and 1863, the Tsarist authorities implemented a number of Russification policies. They banned the Lithuanian press, closed cultural and educational institutions, and made Lithuania part of a new administrative region called Northwestern Krai. These ruthless Russification policies failed owing to extensive network of book smugglers and secret Lithuanian home schooling.

The Russian domination was rather inconsistent with the direction of Lithuanian history. Russians were Orthodox

Christians, Lithuanians were Catholics, Lithuanians used Latin script, as opposed to Russia’s Cyrillic, Lithuanians felt culturally more related to Scandinavians, Poles and Germans, than to Russians, and Lithuania was united by trade routes through the Baltic Sea to Poland, Germany, the Netherlands and Great Britain, rather than through the great rivers and into Russia.

After the Russo-Turkish War (1877–1878), when German diplomats assigned what were seen as Russian spoils of war to Turkey, the relationship between Russia and the German Empire became complicated. The Russian Empire resumed the construction of fortresses at its western borders for defence against a potential invasion from Germany in the West.

On 7 July 1879 the Russian Emperor Alexander II approved of a proposal from the Russian military leadership to build the largest "first-class" defensive structure in the entire state – the 65 km2 (25 sq mi) Kaunas Fortress.

The Kaunas Fortress was constructed and renovated between 1882 and 1915 to protect the Russian Empire's western borders, and was designated a "first-class" fortress in 1887. During World War I, the complex was the largest defensive structure in the entire state, occupying 65 km2 (25 sq mi). The fortress was battle-tested in 1915 when Germany attacked the Russian Empire, and withstood eleven days of assault before capture. After World War I, the fortress' military importance declined as advances in weaponry rendered it increasingly obsolete. It was used by various civil institutions and as a garrison. During World War II, parts of the fortress complex were used by the governments of Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union for detention, interrogation, and execution. About 50,000 people were executed there, including more than 30,000 victims of the Holocaust. Some sections have since been restored; the Ninth Fort houses a museum and memorial devoted to the victims of wartime mass executions. The complex is the most complete remaining example of a Russian Empire fortress.

A more organised movement for independence of Lithuania emerged in the 1880s, with their own publications, and exile institutions, mainly in Prussia. The tsar allowed a Lithuanian nationalist congress to convene in Vilnius in 1905, and the congress demanded autonomy from Russia, restoration of previous borders, and restoration of Lithuanian language as language of instruction in schools.

Between 1868 and 1914, approximately 635,000 people, almost 20% of the population, emigrated from Lithuania. Large numbers of Lithuanians went to the United States in 1867–1868 after a famine.

Before any of Lithuania’s demands vs. Russia were met, World War I broke out and Lithuania was occupied by Germany. At the end of the war, Lithuania declared itself independent. The Bolshevik Red Army invaded and installed a puppet government, but by May 1920, Lithuanian and German forces had driven the Russians out. Lithuania was recognised as independent, and remained so until 1940.

In 1939, Germany took control of parts of Lithuania, but let the Soviets take over, in accordance with the Molotov-Ribbentrop Non-Aggression Pact. In 1940, the Soviet Union invaded Lithuania, installed a puppet Communist government, and the Lithuanian SSR was established (the Nazis re-invaded Lithuania for the period 1941-1944).

The Soviets immediately began various russification measures, and deported tens of thousands of ‘suspected’ Lithuanian people, first in 1941, then for the period 1944-1953 and later. The numbers of Lithuanians in Siberia and Central Asia increased dramatically when this large portion of Lithuanians were involuntarily deported into these areas. After de-Stalinization, however, most of them returned home. Some Lithuanian communities in certain regions of Soviet Union were formed during the Soviet occupation; Later, some Lithuanians were relocated to work in other areas of the USSR; some of them chose not to return to Lithuania, even after it became independent.

It is estimated that some 50,000 Lithuanians still live in Russia.

In 1944, Soviet forces "liberated" Lithuania, and Stalin immediately set about eliminating Lithuanian nationalism. Tens of thousands suspected nationalists were killed and several hundred thousand were sent to Gulag prison camps. All in all, during World War II and Stalin's reign of terror, around one third of the Lithuanian population was killed or deported. Lithuanian guerillas continued to fight the Soviets until around 1953.

Collectivisation and careless industrialisation severely damaged Lithuania's economy and ecology. Soviet rule also brought many Russians to Lithuania, with promises of good jobs and housing.

Both in the 1950s and the 1970s, there were political protests in Lithuania, but it was not until Gorbachev came to power in the mid 1980s, that the winds of change began to blow. Gorbachev himself, in 1987 began discussing more openly the possibility of more autonomy for the Baltic States, and in 1988, a popular front was established, under the name "Sajudis".

A strong expression of the Lithuanians’, Latvians’ and Estonians’ commitment to independence from the Soviet Union took place in 1989, when an enormous number of people from the three nationalities joined hands - literally - in a 600 kilometre (400 miles) chain from Tallinn via Riga to Vilnius, facing west towards Europe, and turning their backs at the Soviet Union.

In February 1990, multi-party elections were held, and the Sajudis movement won a majority in the new parliament. In March, they declared Lithuania independent. Gorbachev sent troops and introduced an embargo. An agreement was reached, by which Lithuania agreed to somehow "freeze" the independence declaration.

In the beginning of 1991, many crises between Moscow and Vilnius occurred over military conscripts and other issues, including the fatal Soviet attacks on Lithuania 11-13 January 1991. But the Soviet Union was falling apart, and in the wake of the failed coup in Moscow in August, Lithuanian independence became a reality.

|

Lithuania’s Prime Minister: The West should have no illusions about Russia

“Russia's decision on its leadership change this year has effectively buried any hopes of a renewal of relations with the West,” Lithuania's prime minister Andrius Kubilius told in an interview with Lithuanian Radio in 2011. "No one should have illusions about how Russia will be ruled for decades to come," he said. Lithuania is among Russia's harshest critics in the European Union and NATO. "All the restart policies or renewal of relations should now be locked in a deep drawer with a simple note attached: 'Here rest expired and naive dreams,'" Kubilius said. He said Putin's decision was not a surprise. Lithuania has most recently locked horns with Russia over natural gas prices. Kubilius' conservative government irked Russia earlier this year by using a EU rule that allows member states to split companies that supply and transport natural gas — a direct blow to Russia's state-runGazprom, which owns 37.1 percent of Lithuania's main gas company, Lietuvos Dujos.VILNIUS, Lithuania — Russia's decision on its leadership change next year has effectively buried any hopes of a renewal of relations with the West, Lithuania's prime minister said. "No one should have illusions about how Russia will be ruled for decades to come," Andrius Kubilius told Lithuanian Radio. Lithuania is among Russia's harshest critics in the European Union and NATO. "All the restart policies or renewal of relations should now be locked in a deep drawer with a simple note attached: 'Here rest expired and naive dreams,'" Kubilius said. He said Putin's decision was not a surprise. Lithuania has most recently locked horns with Russia over natural gas prices. Kubilius' conservative government irked Russia by using a EU rule that allows member states to split companies that supply and transport natural gas — a direct blow to Russia's state-run Gazprom, which owns 37.1 percent of Lithuania's main gas company, Lietuvos Dujos.

|

|

Russia-Lithuania relations should not be held hostage to the past

Lithuanian counterpart Audronius Azubalis.

Relations between Russia and Lithuania should not become a hostage of the past, Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov said after talks with his Lithuanian counterpart Audronius Azubalis last year, ITAR-TASS reports.

“We do not want the historic truth to be forgotten, but we also have a common intention not to make our current relations hostage to the past and hostage to those events for which neither we nor Lithuanian leaders of this day bear responsibility,” he said.

“Assessment of the past events was made long ago – in the last years of the Soviet Union and now by the authorities of modern Russia,” the diplomat said. “We (Russia and Lithuania) have a commission of historians who work rather fruitfully, professionally, without emotions and provoking movements on our common history that had quite a few sad pages.” “Historians know well what a difficult task it is to do this work. But if we do not go along this difficult path, we will not get the historic truth in its entirety,” Lavrov said. “Therefore we agreed that discrepancies existing in the analysis of our common history – and we do not keep it secret – should remain an object matter for the commission of historians. We would like this work to be activated,” he said.

The Russian diplomat expressed confidence that “it will really help to step up contacts between civil societies of Russia and Lithuania, develop youth contacts and build relations for the future.”

Russkiy Mir Foundation Information Service

|

Deportations of Lithuanians to Siberia

The cruel deportations of hundreds of thousand Lithuanians to Siberia during and after World War II is the very saddest chapter in the relations between Russia (USSR) and Lithuania. An exhibition that right now is shown in the famous Balzekas Museum in Chicago shows the true face of these atrocities.

Let us also commend Dr. Audrius Plioplysa marvellous work to collect so many touching letters from some of the exiled Lithuanians. .

Exhibition in the Balzekas Museum of Lithuanian Culture, Chicago |

|

Location, Contact and Link |

|

|

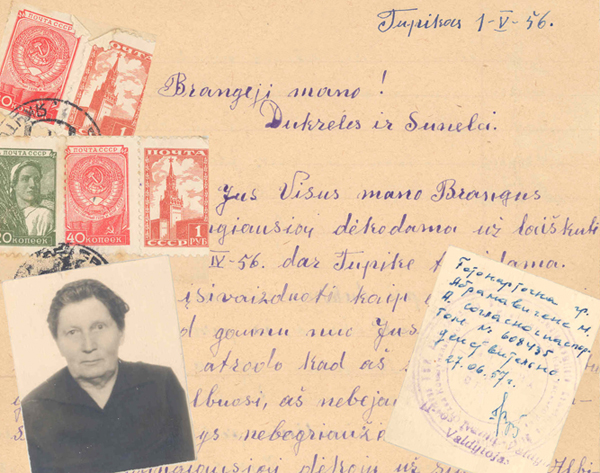

Letters from Siberian Deportees

The Balzekas Museum's Hope & Spirit exhibit and program, commemorating 70 years since the start of Soviet deportations to Siberia, includes 157 original handwritten and personal letters from Lithuanian deportees to their relatives living in London, England; Sydney, Australia; Chicago, Illinois; Bogota, Columbia; Toronto, Ontario; and other cities. Among these letters are 20 written by children who were deported. The exhibit includes 218 original photographs from Siberia and 71 addressed envelopes. All of these items are extremely rare and of immense historical value and are being presented to the public for the first time.

|

|

||||

|

Letter examples, presented by the collector, Dr. Audrius Plioplys |

|

|

||

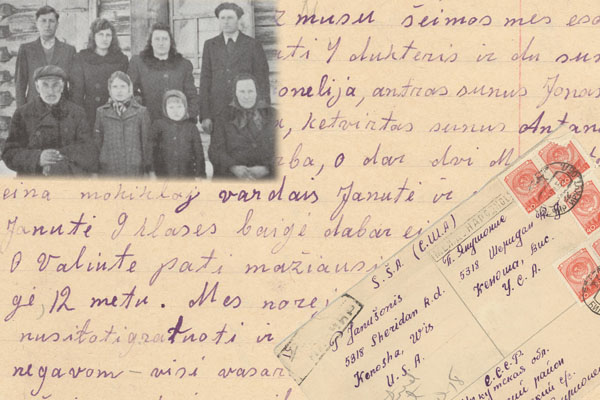

Family of 8 deported

Posted on October 10, 2011

Kazimieras Janusonis with his wife Agota, and 6 children were deported to work in the same collectivized farm in Siberia. The location of the Bilchirsk kolkhoz was in the northerly portion of the Irkutsk region. Agota wrote letters to her brother-in-law, P. Janusonis, who was living in Kenosha, Wisconsin.

She wrote, “We work in the kolkhoz. Our family has 7 members: me, 4 daughters and 2 sons. (She notes 7 family members because when she wrote this letter, her husband had already died–AVP.) The oldest is my daughter Petronelija, then my son Jonas, thirdly my daughter Agota, and fourth, my son Antanas. All 4 work in the kolkhoz. My younger 2 daughters, Janute and Valiute, are students. Janute completed grade 9 and now attends grade 10. Valiute, my youngest, 12 years old, finished grade 4…We did not bring anything with us besides what were able to stuff into one bag. Adequate clothing is very difficult for all of us…Winters are very cold and summers very hot. We are surrounded by mountains and forests. There is little flat ground.”

In another letter she wrote, “We are surrounded by tall mountains which are covered with impenetrable forests. Wild animals live there–polar bears and wolves. We live in a valley near a small stream. We use it’s water because there is no well. Without fur coats, it is not possible to go outside, even for a brief period of time, in the winter. And then, the fur freezes solid as an animal’s horn. Thus, we wear cotton coats. We live with the Buriats (related to the Mongols–AVP).”

Kazimieras Janusonis died in Siberia, shortly after the photograph was taken. After serving 10 years of hard labor on the kolkhoz, Agota and her children were allowed to return to Lithuania. However, they were not allowed to return to their family farm.

On display we have 5 letters and 3 envelopes from the Janusonis family as part of the Hope and Spirit exhibit which I have organized. The exhibit is at the Balzekas Museum of Lithuanian Culture, in Chicago, and has been extended until the end of April, 2012.

Posted in Letters from Siberia

Mother buries her two infants in Siberia

Posted on October 10, 2011

In these two photographs, Veronika Norkunas buries her two young children near the city of Barnaul, in Siberia.

In the top picture, 4 year old, Livija-Liucija Norkunaite is being buried. She was born in Lithuania, and died on September 21, 1941, in Siberia.

In the bottom picture, 16 month old Zenonas Norkunas is being buried. He was born in Lithuania, and died on September 22, 1941, in Siberia.

On one September day, Veronika buried her four year old, and on the next day, her 16 month old.

The pictures were sent to A. Norkunas who was living in Adelaide, Australia.

These young children survived only 3 months after their deportation in June, 1941. They only survived 3 months in Stalin’s new society.

There is no available further information about this Norkunas family.

These two images are from over 230 original deportee photographs from Siberia which are on display in the Hope and Spirit exhibit, which I have organized, at the Balzekas Museum of Lithuanian Culture, in Chicago. Quite literally, due to popular demand, the exhibit has been extended to the end of April, 2012.

Posted in Letters from Siberia

14 months old–deported to Siberia; 14 years old–dead

Posted on October 10, 2011

Zigmas Zarunskis was 14 months old when he, with his family, were deported to Siberia. At the age of 14 years, instead of attending school, he was assigned to work as a lumberjack. While chopping trees, a limb fell down on him, killing him. The photograph was mailed to a relative in Jackson Heights, New York. In it, standing from left to right, are Zigmas’ parents, Pranas and Ona, his younger brother Jonas (who was born in Siberia), and his older sister, Zita. No further information is available about the Zarunskis family.

This photograph is one over over 230 which are on display in the Hope and Spirit exhibit, which I have organized, at the Balzekas Museum of Lithuanian Culture, in Chicago. Quite literally, due to popular demand, the exhibit has been extended to the end of April, 2012.

Posted in Letters from Siberia

Health care and God’s will

Posted on September 2, 2011

Konstancija and Jonas Marmas, with their three children, in the Krasnoyarsk Region of Siberia

The Marmas family was deported, from their family farm in Griskabudis to work as lumberjacks for 10 years. The uncle of Jonas Marmas was Dr. Vincas Kudirka, the author of the Lithuanian national anthem. Possibly it was because of this familial relationship that they were deported.

In this letter, written to Alfonsas Lietuvninkas, in Chicago, Mr. Marmas comments about the health care system. Apparently Mr. Lietuvninkas was having health issues. Mr. Marmas writes: “You wrote that health care costs are expensive. For us, from one aspect, it is very good–we do not have to pay for anything. Along with this, there also are no medicines available. It would be better to pay and at least feel that your health is improving, instead of waiting to see if the illness clears or not. What can you do, if that is God’s will?”

He further wrote that during the winters, temperatures were frequently -55 to -60 degrees Centigrade (-75 degrees F) with 5 to 6 feet of snow. During the short summers the temperature would reach 50 degrees Centigrade (120 degrees F), and at night fall to freezing, destroying even the potatoes that were their main food source. There is no further available information about the Marmas family.

The Marmas family letters and photographs are currently on display as part of the Hope and Spirit exhibit which I have organized, at the Balzekas Museum of Lithuanian Culture, in Chicago. This exhibit, and extensive programs, will continue into January 2012.

Posted in Letters from Siberia

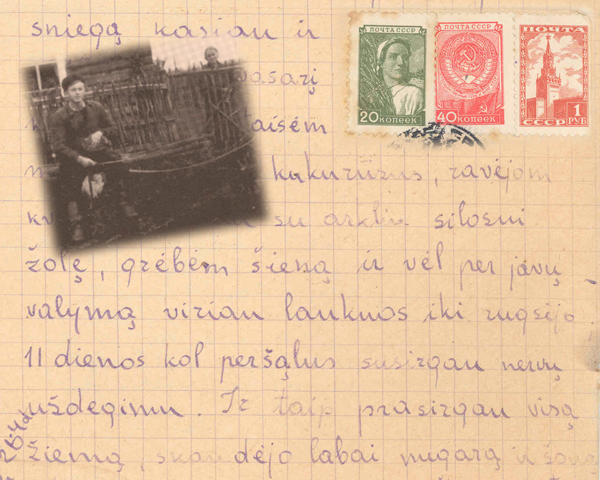

10th grade graduation present: 167 hard labor jobs and meningitis

Posted on August 9, 2011

Dobilas Ralys and his mother in Siberia. The letter was written by his sister, Ramune Ralys, and was sent to their uncle, V. Cizinas, in Paterson, New Jersey. In this letter she details some of her own life events upon being exiled to Siberia with her family. She was attending the 7th grade at the time of deportation. In the Krasnoyarsk District’s farm labor camp (kolkhoz) the middle school was located 2 miles away, which she attended until completing grade 10. At that time, she took over the labor tasks of her mother, who was too ill to work.

The Ralys family had been living in Kaunas, where Mr. Ralys worked as a bank accountant. In 1910 and into the 1920′s he wrote general interest articles under the pseudonym of Vargovaikas (Child of Misery). The family was deported to a forced labor camp to serve a 6 year term. Upon returning to Kaunas, the family was allowed to live in the house that they had previously owned, but only in a portion of the basement. Mr. Ralys died within a year of returning to Lithuania. He was 66 years old at the time of deportation.

In this letter, Ramune details some of the tasks that she had to do. “Shoveled snow…worked as a camp cook…collected and burned straw, planted corn, weeded wheat fields, collected silage, transported logs, transported grains, cleaned grains, and so on. In all, I did 167 different jobs.” During September of the second year’s hard labor, she became ill with what appears to have been a form of meningitis/encephalitis. She suffered the entire winter, but was able to return to labor in the spring.

This letter, and several hundred like it, are on display as part of the Hope and Spirit exhibit that I have organized at the Balzekas Museum of Lithuanian Culture in Chicago. The exhibit will continue through mid-January 2012.

Posted in Letters from Siberia

$4 for one egg, $70 for a pound of butter

Posted on July 18, 2011

Morta Abromaviciene, at the age of 67, was deported to Siberia with her husband Stasys, who was 74. Mr. Abromavicius died 3 years later, while Mrs. Abromaviciene was able to serve her prison term in Tinsk, in the Krasnoyarsk District. After 7 years of hard labor, her health was broken–she was so frail and weak that she was transferred to the Tupik sanatorium, in the Shirinsky District of Khakassia, for one year to recover. It was while she was in the sanatorium, that she was able to write letters to one of her daughters, who was living in Chicago.

In the early 1900′s, Mr. and Mrs. Abromavicius had both, independently, traveled to work in the United States. They met in Braddock, Pennsylvania, where they were married in 1906. With their two young daughters they returned to Lithuania in 1913, and bought a small family farm. All totaled, they had 2 daughters and 4 sons. During the war, one son died, and the other children moved to the United States.

When she returned to Lithuania from Siberia, she found all of her farmhouses burned to the ground. She went to the nearby larger city, Marijampole, where she lived and died 10 years later. She was able to survive only because her children continued to send her packages.

In her letters from Siberia she notes that the winters are very cold, with the temperature frequently minus 40 degrees Centigrade (which is exactly minus 40 degrees F).

She is thankful to her children for the packages that she has received, and mentions the items that she needs to obtain. She notes that when packages arrive, the other residents of the sanatorium crowd around as the package is opened. She gives most of the contents to the other residents, keeping only the essential items for herself.

One time, her daughter made an error and sent her $50 in cash (I am changing the actual amounts into what would be current US$ value, given years of inflation). To exchange this currency into rubles, she had to travel to a bank in a distant city. The travel cost was $32, leaving her very little.

In another letter she notes how expensive even the most basic items are. One egg cost $4. One kilogram of butter, $140–which means $70 for one pound of butter!

Why was this family treated like criminals? Landowners, because they might object to Stalin’s new political system, needed to be either exterminated or deported. This was genocide, pure and simple, on the basis of political motives. This happened to the Abromavicius family, and to millions of other families across Eastern Europe.

The letters of Morta Abromaviciene are on display as part of the Hope and Spirit exhibit, which I have organized, at the Balzekas Museum of Lithuanian Culture, 6500 S. Pulaski Rd., Chicago, Illinois. The exhibit has been extended, and will continue until mid-January, 2012.

Posted in Letters from Siberia

|

Russia and Three Baltic States By Arturas JURGELEVICIUS |

|

The period was extremely difficult for Europe as well as for Russia, and the consequences are being felt in today’s realities. To solve economic and political disputes between these countries, the historical perspective should be taken into account.

Baltic States recklessly seek “Historical justice” Many believe that Soviet Union did a huge damage to the humanity under the presidency of Stalin. Of course, this view might be debated but it is obvious that the victory of Nazis would have brought much more human devastation and bigger tragedy to the whole Europe. Anyway, official political line of the Baltic States claims that after World War II, Soviet Union and now Russia as legitimate successor of Soviet Union was/is responsible for what happened and have to apologize and reimburse the damage done during that era. As history has shown Soviet Union delegates and even modern Russia’s officials have already done so at least four times. First, Stalin’s cult and crimes were publicly denounced and condemned during the 20th Congress of Communist Party of Soviet Union by speech made by Nikita Khrushchev, the leader of Communist party and the Soviet Union. That is to say that this is the first time after Stalin’s epoch when officials of Soviet Union revealed and criticized the dictatorship of Stalin and faulty policy led by him towards some human and economic activities. Secondly, special Soviet commission under Alexander Nikolaevich Yakovlev, in December 1989, the commission concluded that the protocol had existed and revealed its findings to the Soviet Congress of People's Deputies. As a result, the first democratically elected Congress passed a declaration in December 1989 admitting the existence of the secret protocols, condemning and denouncing them. In 1992, the document itself was declassified only after the dissolution of the Soviet Union. Third, the sovereignty and independence of the Baltic States was recognized by the first democratically elected president of Federation of Russia: B. Yeltsin. He recognized the independence of the Baltic States and invited the rest of the world to do the same. That is to say that by recognizing sovereignty of the Baltic States, Russia automatically rejected the idea of its bid to pretend to restore the influence in this region. Russia recognized all freedoms and respects towards these countries establishing diplomatic and economic relations with Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia. Fourth, during EU-Russia summit in 2008 president V. Putin was asked by an Estonian journalist “why is that so hard to recognize the fact of the occupation of the Baltic states?”. The answer of the president was as following: "<…...>The conspiracy happened in 1939 between Russia and Germany. I believe it was a conspiracy. What can we do now? It was the reality at the time when small countries were involved in the reality of those days. <…> in 1989 the Soviet Congress of People's Deputies declared that Molotov and Ribbentrop pact did not reflect the real will of Soviet people and recognized the illigitimate action taken by them. It was condemned. What more accurate is possible to say about this? What else? How many times can we repeat that? Every year? We think that everything possible is said about that and this question is already closed". As it is seen both Soviet government and the government of modern Russia recognized de facto and de jure the independence and territorial sovereignty of the Baltic states which actually means that all claims to get this territories back is faulty and there is no foundation for such claims. Moreover, it is recognized that conspiracy between two states (Nazi German and Soviet Union) had no legal foundation, it was in conflict with international law and it is absolutely illegitimate. Consequently the destruction of the sovereignty of the Baltic States was condemned and sovereign power of the national states was recognized.

First, to restore the supply of the crude oil via Druzhba (Friendship) pipeline which broke down in 2006 and Russian officials said it would take at least several years to restore it. Of course, since Russia is being considered as “aggressor” and seeking to rebuild its power in the Baltic States, it was accepted as political blackmail. At that moment Lithuanian president pointed out that "Today we know that oil will not flow through this pipeline any more", he told during a conference. Meanwhile, Russian technical watchdog Rostekhnadzor said in September that Transneft would need at least another 18 months for repairs, meaning that the pipeline could not be reopened before the end of 2009. Even if this technical problem was politicized and it was being tried to create the image of Russia as an “unreliable partner”, the pipeline was reopened on the same time as technical experts predicted. Second, to solve the conflicts between Georgia and Moldova: it is valuable to stress that it is difficult to unmask the real interests of the Baltic States in Caucasus and Moldova. It is more seen as trials to damage Russian security interests at the same time harming EU foreign policy. Third to encourage Russia to cooperate in criminal cases of the killings in 13th of January 1991 when Omon (Russian special intelligence service) killed the rebellions. Russia commented on it proclaiming that according to the then law Omon protected the interest of Soviet Union and acted accordingly to its constitution. Apparently all these issues might be solved bilaterally, but the Baltic States use Europe Union as an instrument to solve their chronic problems. For example Lithuanian conservative party “Union of homeland” passed “The reimbursement for occupation damage” law in 1999 before going to step down from the ruling government. Anyway this law has been never implemented or at least it has been never trying to be implemented because Russian officials ardently respond to these attempts. After more than a decade of playing a cat with a mouse, newly appointed minister of foreign affairs of Lithuania Audronius Ažubalis retreated and said that, “at first Lithuania should do its homework and estimate what real damage has been done and then deliver the claim“. Unofficially some representatives speak about 25 billion (almost three times more than the annual budget of the country) euro harm. Recently new numbers showed up. Latvia's Foreign Minister Maris Riekstins estimated the losses from Soviet occupation are $18.5 billion. Is money dearer than national pride? But it is not clear how this number is estimated. If we follow this logic, then Russia has the right to claim for compensation for building roads, manufactures, the world biggest nuclear plant in Lithuania (in 2010 it was closed as precondition for membership in EU), harbors, Mazeikiu refinery (Lithuania), hundreds of apartments and dozens of various buildings etc. These initiatives of reimbursements of “losses” might set precedent for other countries which were involved in these historical games. If all 15 former member states of Soviet Union claimed for the compensation for “damage” done during Soviet epoch what would Russia do? There are tremendously huge problems within Russia as well and economic ones. So if Russia would try to reimburse the claims of former member states, it would take many decades of payments at the cost of own Russian citizens. Anyway there is very little chance that these initiatives will come true in the nearest future. It is worth mentioning that former Soviet Union’s states try to use different international organizations to do harm to Moscow.

What is so offending for the Russian audience in this document? In fact, Russians don't dispute the totalitarian character of Stalin's rule, mostly informed about the order in their country in that time from their grandparents. This fact does not need approval from European neighbors. Russians are rather outraged with the obvious hypocrisy: the document suggests that only the USSR and Germany were the evil states of the XX century, while other Europeans were "warm and fuzzy", never being involved in infringement of human rights, and in military atrocities. But if other Western powers were so impeccable, why did they concede half of Europe to Hitler, leaving Russians alone with the totalitarian adversary? Why did they hesitate for such a long time before establishing the anti-Hitler Coalition? Was it Stalin who paid for this hesitation, or millions of Russian families? Have our Western neighbors really followed the UN Human Rights Declaration since the times of the Crusade? Have all of them condemned Hitler in his cradle? "Our respected partners forget that the subject of totalitarianism is much broader, and that totalitarian regimes existed also in Spain, Portugal, and Greece, and that the European history is far more variable to reduce it to the times of World War II", reminds Mr. Kosachov. Other disputes arise when it comes to the Baltic States. In the last few years, a new idea of rewriting European history appeared. That is to say that the most debatable event of last century is the World War II. The Baltic States claim that the most brutal and humiliating war was initiated not by Germany but also by the Soviet Union. This brings harsh and operative responses from Moscow. In modern politics history is attached to political realities that is to say that by putting blame on Russia as one of the initiator of World War II, western countries want to diminish Russia’s growing influence in Europe and in the world and restore its reputation which they lost after “Munich agreement” in 1938. It is seen how former members and the Baltic States are using international organizations as the instruments to revenge to Russia for so-called “occupation”. This adopted resolution is only a segment of the strategy. By accepting resolution of anti-Russian coalition will have at least some sort of legitimate basics for the claim of the compensation in the future. Concluding historical perspective in the relations between the Baltic States and the Federation of Russia it is important to notice that even professional historians are not able to properly evaluate or interpret the extraordinary events of the 20th century. Any trials of rewriting history or the use of the history for political purpose will be strongly rejected by Moscow and will not bring any neither political nor economic benefits for the Baltic States or any other country in the relations with Russia. As a result all these disputes caused by extraordinary and harsh historical circumstances reflect themselves on economic and political agenda as well. With collapse of Soviet Union, Baltic states always tried to “escape” from Russia’s sphere of influence. Finally they became a part of European Union and NATO in 2004. Notably this happened relatively in a short period of time. Probably that is because Western countries wanted to gain influence over Eastern European countries sooner than it would do Russia and diminish its dominance. As it is seen now, Baltic States started using their opportunities in western organizations in order to widen their own old wounds.

Contrary to Estonia, Russia remained the main export market for Latvia also during 1990s. In 1996 exports to Russia comprised nearly 25% of Latvia’s total exports. The share of goods imported from Russia remained slightly smaller, staying near 20%. In 2004, the trade deficit between Latvia and Russia was 8.5 times greater than the deficit of Latvia’s total external trade. The volume of Lithuanian exports to Russia amounted to 3.4 billion LTL (nearly 1 billion euros). Compared to 2004, exports increased almost 44%, which indicates that Lithuanian trade with Russia grew faster than Lithuanian trade in general. Altogether, Lithuania imported goods from Russia in the sum of 11.9 billion litas (3.4 billion euros). Within a year, imports grew 51.3%. In comparison with previous years, Russia’s share in Lithuanian imports has been rising steadily, almost reaching the 1996 level in 2005 (29%). As it is seen Baltic States and Russia have a great trade turnover in general. Anyway the trade balance with Russia always remained negative. That is mainly because Baltic States import oil, gas and other raw materials from Russia. Negative trade balance was emphasized in the recent years mainly due to the growing oil prices. Also this fact could be explained that export to Russia is more difficult than export to Baltic States which apply EU rules because Russia implies many non-tariff barriers such as quotas, strict licensees. Also, the devaluation of rubles in the last decade caused the cheaper Russian export to Baltic states meanwhile the commodities from Baltic region became more costly in Russian market. The same must be said about present economic crisis, when Russian government gradually devaluated rubles to keep its export alive. So these reasons caused deep trade deficit for Baltic countries. Only Lithuania had higher volume of foreign trade with Russia than other Baltic neighbours (Estonian exports to Russia were 155.9 million EUR and imports from Russia 491.4 million EUR in 2003, for Latvia respective figures were 137.5 million EUR and 405.3 million EUR, for Lithuania 548.5 million EUR and 1931.6 million EUR). As it is known now, Russia, Kazakhstan and Belarus have formed the Common Custom Union which came into force on July 1st. This growing custom wall nearby the Baltic States’ borders will affect their economies as well. For example, Lithuanian Ministry of foreign affairs has estimated that national exporters will pay 65 million litas (20 million euro) additional taxes only because of new tax system appeared in the Custom Union. That is to say some industries of the Baltic States might be seriously damaged and probably will get no prerogatives or exceptions from Russian government. Such policies might distance the Baltic States from trade dependence on Russia in the long term, since Baltic States will be forced to search for new markets and make their industries more efficient. On the other hand, these industries will gain big loses in short term. It might be more painful in the light of current economic crises since unemployment rate is one of the highest among the European Union member states. In any case the Baltic States will heavily be depended on Russian natural resources including oil and gas. Countries pay the world price for these recourses even though they are located close by Russian borders. All of three Baltic States get nearly 90% of oil and 100% of gas from Russia. Moreover, the closure of the nuclear plant, built by Soviet, in Lithuania, in 2010 increased the energy dependency upon Russia. As following Lithuania is planning to build new nuclear power plant and in this way to create common energy policy of the Baltic Sea region including the Baltic states, Poland and some of Scandinavian countries. Anyway, the real future of this project seems to be vague. There was an attempt to create some companies responsible of managing and organizing this program but it was disbanded since it did not fulfill the requirements of the European law. Also countries do not agree on the distribution of the electricity among countries which causes the absence of the strategic investors since this project was extremely expensive. As a response to such energy policy Russia has suggested to participate to building up the nuclear power plant in Kaliningrad exclave. However this proposal has not received any serious attention. Russia tries to promote very expensive and important project called Nord Stream which will go under the Baltic bypassing the Baltic States and Poland. Even if it is much more expensive to build pipeline under the sea it is much safer geopolitically for Russia. This might be considered as a response of Russia because of unfriendly posture of Baltic States towards it.

This happened soon after Georgia-Russia military conflict as a symbol of mutual trust between Russia and France and response to Georgian aggression. Anyway, the Baltic States raised their concern about this warship that might be used against them. As a result NATO declared its plans about military exercises in the Baltic States, although NATO claimed there is no link between these two cases.

|

|

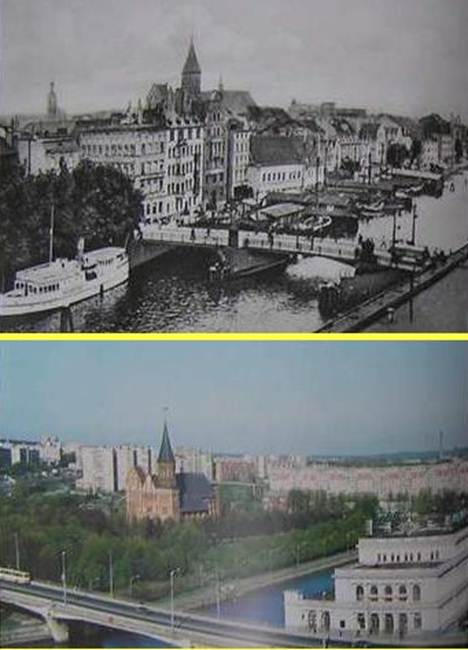

The Baltic Kaliningrad By Grant Heard From Prussia to Russia: a history of the region The Kaliningrad region was originally called the Samland, which was originally inhabited by the Prussian tribes whose language and culture, although has since died out, was similar to Lithuanians and Latvians of today. The Prussians, before the arrival of the Germans, were not Christianized, nor were they highly organized in trade or military. It was when these tribes proved to be difficult to defeat that the Teutonic Knights were called in to take over. They were tempted by the prospect of land and privileges from both the German Empire and the Catholic Church, which included grants to the Teutonic Order of full sovereignty over all the land it would conquer from the Prussians. The Prussians resisted the Teutonic Knights. An early account of the conquest of the Samland comes from the Livonian Rhymed Chronicle, which describes the conquest of Master Anno of the Teutonic Knights as he led the crusaders into the wilderness of the Samland: The land is almost surrounded, being on the peninsula, by the wild seas, which had been a protection for it. No army had ever invaded there, and on the other sides no one can fight against it because a wild stream, wild and deep, flows along it… A narrow peninsula extends toward Memel, and there the Christians came with their stately army. The Christians rejoiced. They found the great forest of the Samites there. It was wide and thick, not of puny saplings, but trees so large that they served as a bulwark… The Christians came upon it and vowed not to rest till it had been cut in two… Then, when they had cut and slashed through the forest, the army advanced directly into the land. The Samites learned that they were visited by guests who wished to do them harm. Although this raid was a success, as the crusaders passed deeper into the forest, they were ambushed and all but annihilated. However, the crusaders pressed on, and new attacks were launched, but from Prussia in the south, instead of Livonia to the north. The Teutonic Knights conquered the region and advanced their frontiers from Prussia to the south bank of the Memel River. It was then that Koenigsberg was founded in 1256, named in honor of King Ottokar of Bohemia, who had brought large armies on crusade to Prussia. Prussians were granted a great deal of rights under the Teutonic Order. Prussians were much more numerous than the Germans, mainly because it was difficult to convince Germans to immigrate to this land because of its harsh, swampy landscape. Thus, the Prussian peasants were treated like German peasants and even lived side by side with each other. In the Samland region, the Prussian language and customs survived until the seventeenth century, being the last region where the Prussian died out. The Prussian culture died out because of Germanization. The Prussian peasants could even rise to the status of freemen. These freemen were allowed to own land and estates. They enjoyed many rights that the Germans did and were even treated like Germans. This helped to facilitate the Germanization of the Prussians. It also helped Prussia to become a country of peasants and landowners, a country in which the rest of the nobility was less important and less elevated above the rest of the population than it was elsewhere. And Koenigsberg was to remain quite autonomous from the rule of higher nobility in the years to come. Under the Teutonic Order Prussia grew rich, and as the prosperity and freedom of the aristocracy and peasantry grew, the more the people began to feel “dominated” by the Teutonic Order, who was felt to be an alien ruler. So when the Order found itself in a long war with the Duchy of Lithuania and Poland in the fifteenth century, its people were sometimes on the side of the enemy. This is because the Polish had a more liberal form of government where the nobility were becoming much more powerful and the start of republicanism were forming. The Teutonic Order lost a number of battles, including the Battle of Tannenberg, which soon led to the Second Peace of Thorn in 1466. Here the Order lost its independence to Poland. West Prussia, which included the major trading center of Danzig, was given to Poland. However, East Prussia was left to the Order, but only as a Polish feoff. The Order was finally dissolved during the Reformation in 1525 by the last Grand Master of the Order, and he then became ‘Duke of Prussia’, though still under Polish feudal supremacy. Koenigsberg was one of Prussia’s most important trading centers up till the sixteenth century, second only to the port of Danzig. Some of Koenigsberg’s main export items included rye, corn, hemp malt and waxes, and it had many guilds. The city had about 30-40,000 inhabitants at the time, which was even larger that Berlin. Politically, Koenigsberg was organized on a fairly democratic basis, base on the Third Estate system. Because of their power and privileges, the town did not hesitate to oppose the nobility. This in turn caused struggles between Koenigsberg and the nobility, and helped to prevent Prussia from becoming a noblemen’s republic. Even after the famines and the Plague hit the region during the mid-sixteenth century and their trade had declined, the town still would not relinquish its autonomy. It wasn’t until 1674 that the town finally surrendered much of its autonomy and agreed to pay higher taxes to the nobility when Fredrich William marched several thousand troops by surprise into the city. In 1701 Koenigsberg became part of the Prussian Empire. The city became the focal point of the unification of the Prussian empire when Fredrick I was crown King of Prussia in Koenigsberg. Under this new rule immigrants flooded into Eastern Prussia, mainly to escape religious prejudice. People from all over Europe, including Jews, were welcomed into the Prussian state. They were then settled in East Prussia to help replace the losses experienced by the plague. There was not the overwhelming harassment and discrimination, either ethnic nor religious, then that would be experienced in the German Reich. This was also a time of the rise of the great Prussian militarism. The military became a powerful force as loyal, professional soldiers replaced mercenaries. In 1756 Koenigsberg and East Prussia came under the brief rule of Russia, as the Seven Year’s War left the area almost completely defenseless. But this occupation would be short lived as the Prussian army reclaimed the territory after the battle of Zorndorf in 1758. This brief occupation did not bring about radical change in the population. As Sabastian Haffner writes, “the war, in a manner of speaking, passed over the heads of the people; they ducked and let the storm blow over.” By the nineteenth century, the tide of nationalism swept throughout Prussia. This nationalism helped the great Prussian politician, Otto von Bismarck, to channel power in order to establish the first German Reich by 1871, after a series of wars with Austria, France and Denmark. From this time on Koenigsberg and East Prussia were to be absorbed into Germany, where it would remain as such until 1945. After World War I, East Prussia was then separated from the German mainland by Poland by the Versailles Treaty, connected only by a corridor through Polish territory. However, prior to World War II, Hitler connected the German mainland with East Prussia. When Poland resisted, Hitler was given an excuse to attack Poland to reconnect the region with Germany. This fact still weighs very heavily on the memory of many Poles and is part of the reason why Poland fears a Russian corridor to Kaliningrad. Koenigsberg fell to the Red Army in April 1945. The population was completely wiped out of Koenigsberg during the war. All the inhabitants of Koenigsberg were killed by the advancing Soviet Army, deported to other parts of the Soviet Union, or escaped to the German mainland. Koenigsberg was surrendered to the Soviet Union in 1945 at the Potsdam Conference, when the Western leaders agreed to the Soviet proposal …That pending the final determination of territorial questions at the peace settlement, the section of the western frontier of the USSR which is adjacent to the Baltic Sea should pass from a point on the eastern shore of the Bay of Danzig to the east, north of Braunsberg-Goldap, to the meeting point of the frontiers of Lithuania, the Polish Republic and East Prussia. Stalin did not have any historical or legal basis for his desire to control Koenigsberg, but he did present a justification: the territory would be a just compensation for the efforts and losses experienced by the Red Army during World War II and the region was to serve as a vital base for Soviet military power. The strategic view that Koenigsberg served was the Russian Soviet Socialist Republic now possessed an ice-free port located closer to the region of potential confrontation with the West than the Soviet bases before the war and that was much less vulnerable than the Soviet facilities in the Finnish Gulf. Of the other ice-free ports that were acquired by the Soviet Union by the annexation of the Baltic States, Kaliningrad was considered to be superior to the rest. The town of Koenigsberg was almost completely destroyed by 1944 by the devastating air bombing of the British Royal Air Force. In fact, almost 90% of the buildings were completely destroyed by the British air campaigns. When the red Army arrived, the rural areas surrounding the city suffered great damages. When the Soviet Union claimed the territory, the first order of business was to clear away the rubble that was left and to eradicate the area’s German past and to replace them with a Russian veneer. One method of doing this was to rename the cities and towns that were in the region. Koenigsberg was renamed Kaliningrad after the former president of the Soviet Union, Mikhail Kalinin. Soviet-style architecture and concrete housing blocs then replaced many of the buildings in the city. Today little remains of the features of the former Koenigsberg. However, as Romuald Misiunas and Rein Taagepera have claimed, the bulk of the construction carried out in Kaliningrad dates from the 1970s or later, and by the early 1990s, a lot of destruction still remained outside of the city. During the Soviet period, the bulk of the economy was centered around the military establishment in the region, even though the fishing industry and paper processing were also important. Kaliningrad was considered one of the most heavily militarized regions in all of Europe during the Cold War. This is why the region was cut off to foreigners and most Soviet citizens until the late 1980s. The region’s population remained isolated from the West because no ships were even allowed to dock in the Kaliningrad port. AFTER THE FALL THE MILITARY INSTITUTION This has caused many politicians to stress the importance of the Kaliningrad region to the military security of the region, while at the same time, has caused some anxiety among its neighbors Poland and Lithuania. In fact, Polish Foreign Minister Bronislaw Geremek, in 1998, said that Kaliningrad “is a threat not only to Poland but also to European security.” The amount of forces in Kaliningrad is unknown. However, the International Institute for Strategic Studies in London estimates a total number about 20,000 soldiers currently in Kaliningrad, of which 14,500 belong to the ground forces, and the rest to naval and border forces, and the interior troops. There are two Russian submarines, two destroyers, four frigates and 30 other surface ships in the Baltic Sea. It is this military complex in the region that Russia might use to further its image as a superpower and a bargaining chip to mark its influence within the Baltic Sea region. ECONOMIC TROUBLES AND OUTLOOK However, the region is among the 5 regions with the Russian Federation with the greatest number of enterprises with foreign capital. Kaliningrad has a Special Economic Zone, which allows foreign countries to produce goods in the region and then transport them to the Russian mainland without having to pay the higher export duties and taxes they usually have to pay to Russia. At the beginning of the decade Kaliningrad had a Free Economic Zone, in which foreign companies and ventures could transport goods free of duties and tariffs, but this was changed in 1996 to the Special Economic Zone when Russia began to lose millions of dollars (and other forms of hard currency from the West) and wanted to bring the oblast under tighter federal control. The federal government has invested almost 1 billion rubles into the program, but it still needs foreign investment to modernize its economy. The Special Economic Zone, in theory, is to help the Kaliningrad region in several ways. First, it eases the problems faced by Kaliningrad in being separated from Russia. Second, it supports a region that is severely lagging behind the rest of the Baltic states economically. Third, it improves European access to Russian markets. This last point is important because Kaliningrad relies heavily on its trade with foreign countries for its economic need. This was having an adverse effect on the economy of Kaliningrad because many local producers could not compete with the goods that were flooding the market from other countries. In 1999 there were 6,150 registered small enterprises and firms in the oblast, which accounted for only 20 percent of the economic activity of the population of the region, bringing in only about 12 million dollars of taxes. In fact, 80% of Kaliningrad’s consumer goods are imported. Kaliningrad needs to build up its own large scale industry in order to compete with its neighbors Poland and Lithuania, but to do this foreign investment is needed to help build up the region’s industrial infrastructure. SOCIAL ILLS AND IDENTITY The Kaliningrad exclave’s ethnic make-up is unmistakably Russian. Today the population of the Kaliningrad oblast numbers around 927,000 people, of this 683,600, or 78.5%, are ethnic Russians. The other countries that may have possible claim to the territory (Poland, Lithuania and Germany) combined to only about 2% of the population. After over half a century, many of the local Russians were born and raised in the Kaliningrad region, which gives the region its Russian ethnicity, although with special characteristics. Anna Romanovna, a Kaliningrad resident, says that: “All these reasons (political situation, economics, and ethnicity) make Kaliningrad looking more like Moscow (relatively, of course), just because it differs from other typical Russian cities in many ways: they don't have border problems which we have with several states between us and the main territory of Russia, it differs ethnically, it looks different because of its specific architecture, etc. But, anyways, it's certainly a Russian city!” The overwhelming Russian population would make it extremely difficult for any country to acquire the region from Russia. FOREIGN RELATIONS WITH KALININGRAD’S NEIGHBORS “The geographical location of the Kaliningrad region makes different speculations about the enclave's future possible… Some of them speculate about the region being separated from the "coastal" Russia and being autonomous. Others speak in favor of the enclave being integral part of the country. Sometimes we hear rumors from Moscow about our region being sold to Germany in order to cover Russian debts. I still remember the example of my younger brother when it came time to choose between the English and German languages to study at school (we are offered to choose one of them to be "the main" and the other to be "the bonus one"). My mother insisted on him learning German, because we could not predict the way the things would go. To best understand the concerns that Kaliningrad has with other countries, we must first look at the relationship that Kaliningrad has with its other neighbors. POLISH IRRITATION AND CONCERN One of the biggest sore spots has to be the calling for a corridor by the Russians between Belarus and Kaliningrad. Russia would like to build a corridor from Belarus for the transportation of military equipment and troops and goods to the isolated exclave. For many Poles, a Russian corridor through Polish territory sparks many memories of the German connection to East Prussia through the Polish Corridor before the war and the period of Soviet domination during the second half of the Twentieth Century. There has been a loud outcry from many Polish politicians that no corridor will be built on Polish soil, thereby furthering the mistrust of the two countries. However, Poland finds it is not in its interest to be anti-Russian, especially with Kaliningrad. Poland has maintained that Kaliningrad is an inseparable part of Russia and has made no claims to the region. For membership into the EU, Poland has to maintain well-defined borders with its neighbors, which it has done. Any dispute with Russia for Kaliningrad will only weaken its plea for admission. Additionally, there is a sense of cooperation between Kaliningrad and Polish officials to help to lessen the amount of smuggling along their mutual border. LITHUANIAN FRIENDSHIP “Following the re-establishment of Lithuania’s independence, Kaliningrad was perceived as a risk and a threat to the stability of the region. Over recent years, Lithuania has been deliberately working to make the Kaliningrad region be seen as an opportunity for regional and European co-operation. Our national interest is to co-operate with neighbors that share the same values. We should like the Kaliningrad region to become an attractive partner for economic and cross-border co-operation and a ‘window of opportunity’ for wider co-operation between Russia and the enlarging EU.” Like Poland, Lithuania does not have any territorial disputes with Kaliningrad and has been working hard to maintain good relations. At the present time, Lithuania is one of the Kaliningrad region’s largest investors. Twelve percent of Lithuania’s overall trade is with Russia and has invested about 3.9 million dollars and has established 32 new enterprises in the Kaliningrad region within the last year. Lithuania has worked very closely with the EU and the Council of Baltic States to help implement reform in Kaliningrad. It also has implemented a visa-free regime with the citizens of Kaliningrad. Citizens of Kaliningrad and Lithuania are allowed to travel back and forth across each other’s borders and stay in the other country or oblast for a month without the need for a visa. Lithuania has stated that it will not abandon the visa free regime of the Kaliningrad region’s residents, but has maintained that as Lithuania is integrated into the EU it will eventually have to review the issue of the visa free travel with non-EU countries. Lithuania also allows the Russian military to use a corridor that runs through its country to Kaliningrad, but under certain restrictions. GERMAN INTERESTS Germany has been involved in economic ventures in the exclave, although rather hesitant because of the uncertainty of laws and poor infrastructure. One such venture was with the German automobile manufacturer, BMW. In 1999, the German car company BMW created a 25 million dollar joint venture in Kaliningrad. The company has taken over a Soviet naval factory that was first built by the Germans before the war to make U-boats. This will hopefully have a good effect on the economy of Kaliningrad and Russia. The venture employs about three hundred workers, with an average wage of about 3,500 rubles a month (USD $130), and the cars that are produced in Kaliningrad will be sold in Russia with 30% of the cost of each car will stay in Russia. BMW’s strategy focuses on advanced sales and tax breaks. Duties comprise 60% of the price of imported BMWs in Russia. But Kaliningrad, with its special economic zone, grants importers immunity. Moreover, BMW’s Russian partner in Kaliningrad is assembling the cars cheaply. In all, BMW hopes that costs will be about 20% less than BMW cars that are imported into Russia. The success of this venture may create more interest of other companies looking to take advantage of the Russian market. This is one reason why the Russian presidential administration has bought 130 cars from Kaliningrad for about seven million dollars and plans on restraining from taxing the firm until the operation is on firm ground. Of course, this firm is starting small but success could attract other investors that have been wary of venturing into Kaliningrad due to the financial crisis of 1998 and Kaliningrad’s high crime rate and social problems. Conclusion

|

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

VilNews e-magazine is published in Vilnius, Lithuania. Editor-in-Chief: Mr. Aage Myhre. Inquires to the editors: editor@VilNews.com.

Code of Ethics: See Section 2 – about VilNews. VilNews is not responsible for content on external links/web pages.

HOW TO ADVERTISE IN VILNEWS.

All content is copyrighted © 2011. UAB ‘VilNews’.

Click on the buttons to open and read each of VilNews' 18 sub-sections

Click on the buttons to open and read each of VilNews' 18 sub-sections

The life-long dream of Stanley Balzekas, Jr., to preserve for posterity the wealth of material pertaining to Lithuania's history and culture was realized when he opened the Balzekas Museum of Lithuanian Culture in a "two-flat" building next to his auto dealership on Archer Ave in Chicago on June 22, 1966. His personal collection of art, armor and rare maps was donated and placed on display. Still the president of the museum's board of directors, Stanley Balzekas has seen his museum grow to a major repository of publications, cultural artifacts, and arts not only of Lithuania, but also of the Lithuanian immigrants to the United States and the generations that followed them. The Museum quickly outgrew the available space on Archer Ave and moved to its present, greatly expanded facilities in 1986. With a substantial staff, many volunteers, and many hundreds of donors and members, the Balzekas Museum of Lithuanian Culture is a major player in the Lithuanian

The life-long dream of Stanley Balzekas, Jr., to preserve for posterity the wealth of material pertaining to Lithuania's history and culture was realized when he opened the Balzekas Museum of Lithuanian Culture in a "two-flat" building next to his auto dealership on Archer Ave in Chicago on June 22, 1966. His personal collection of art, armor and rare maps was donated and placed on display. Still the president of the museum's board of directors, Stanley Balzekas has seen his museum grow to a major repository of publications, cultural artifacts, and arts not only of Lithuania, but also of the Lithuanian immigrants to the United States and the generations that followed them. The Museum quickly outgrew the available space on Archer Ave and moved to its present, greatly expanded facilities in 1986. With a substantial staff, many volunteers, and many hundreds of donors and members, the Balzekas Museum of Lithuanian Culture is a major player in the Lithuanian

The relations between the Baltic States (Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia) and Russia are complicated not only nowadays but in the past as well. The geographical location of the Baltic States makes them strategically important for Russia’s national security as today as in the past. Probably all problems of these countries are laid down in the 20th century’s history.

The relations between the Baltic States (Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia) and Russia are complicated not only nowadays but in the past as well. The geographical location of the Baltic States makes them strategically important for Russia’s national security as today as in the past. Probably all problems of these countries are laid down in the 20th century’s history.

[…] Read more… […]