THE VOICE OF INTERNATIONAL LITHUANIA

|

VilNews has its own Google archive! Type a word in the above search box to find any article.

You can also follow us on Facebook. We have two different pages. Click to open and join.

|

|

War 1919-1920

The Polish–Lithuanian War was an armed conflict between Lithuania and Poland in the aftermath of World War I and Lithuania's declaration of independence 16 February 1918. VilNews' Associate Editor Vincas Karnila today introduces our readers to a series with a total of four articles about this war and the consequences it had for the relationship between the once good neighbours Poland and Lithuania. The conflict primarily concerned territorial control of the Vilnius Region, including Vilnius, and the Suwałki Region, including the towns of Suwałki, Augustów, and Sejny. According to Lithuanian historians, the war was part of the Lithuanian Wars of Independence and spanned from spring 1919 to November 1920. According to Poland, the war included only fighting over the Suwałki Region in September–October 1920 and was part of the Polish–Soviet War. After Vilnius was occupied by the Russian Bolsheviks in 1919, the government of the Republic of Lithuania established its main base in Kaunas. When Vilnius was forcibly annexed by Poland, Kaunas became the temporary capital of Lithuania, a position it held until 28 October 1939, when the Red Army handed Vilnius back to Lithuania. The Constituent Assembly of Lithuania first met in Kaunas on 15 May 1920. There were no diplomatic relations between Poland and Lithuania until 1938.

|

Introduction

As

usually happens, the end of one hostility often results in the beginning of

other hostilities. This was the case between Lithuania and Poland after the end

of the First World War. With both countries in a state of war with Bolshevik

Russia, defending themselves against Russia’s attempt to recapture and occupy

the two countries that had just recently regained their independence, this

helped to set the stage for armed conflict between the two neighbors. This

combined with one country’s plan to control part of Europe, claims to land

based on its population and the continued “carving up” of smaller countries by

larger countries all helped to create what was known as the Polish – Lithuanian

War which resulted in Lithuania losing its capital of Vilnius and other parts

of its country to Polish occupation during the interim war period.

Dear readers we would like to invite you review this series which will offer insight as to what led to the conflict, the reasons and justifications, the participants, the areas of action and some of the key events. As always we warmly welcome any additional information and any comments you would like to share.

Su pagarbe Vincas Karnila, Associate editor

vin.karnila@VilNews.com

Part 1 of 4 - THE BUILD UP

MILITARY DEVELOPMENTS

World War I ended on November 11, 1918 when Germany signed the Compiègne Armistice. On November 13, Soviet Russia renounced the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk (After signing the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk March 3 1918, Bolshevik Russia lost the European lands it annexed in the 18th century and 19th century. Most of today's Poland, Belarus, Ukraine and the Baltic States were passed to the government of Germany, which in turn decided to grant these states limited independence as buffer states) and began the Soviet westward offensive of 1918–1919. The Bolsheviks followed retreating German troops and attacked Lithuania and Poland from the east trying to prevent their independence. They attempted to spread the global proletarian revolution, establish Soviet republics in the region, and join the German and the Hungarian Revolutions. The Soviet offensive sparked a series of local wars, including the Polish–Soviet War and the Lithuanian–Soviet War. At first the Soviets were successful, but came to a halt in February 1919. In March–April both Lithuanians and Poles began their offensives against the Soviets. The three armies met in the Vilnius Region. The Polish–Lithuanian relations were not immediately hostile, but grew worse as each side refused to compromise. On April 19, 1919, the Polish Army captured Vilnius.

The

advance of Polish (blue arrows), Lithuanian/German (dark purple arrows) against

the Soviet forces in early 1919. The blue line shows the Polish front in May

1920. The red line shows the Soviet front in February 1919

At first, both Poles and Lithuanians cooperated in their offensive against the Soviets, but soon the cooperation gave way to increasing hostility. Lithuania claimed neutrality in the Polish–Soviet War. As the Polish Army forced its way further into Lithuania, the first clashes between Polish and Lithuanian soldiers occurred on April 26 and May 8, 1919, near the village of Vievis. Though there was no formal state of war and few casualties, by July newspapers reported increasing clashes between Poles and Lithuanians, primarily around the towns of Merkinė and Širvintos. Direct negotiations in Kaunas between May 28 and June 11, 1919, collapsed as neither side agreed to compromise. Lithuania tried to avoid direct military conflict and submitted its case for mediation to the Conference of Ambassadors (The Conference was formed to enforce peace treaties and to mediate various territorial disputes among European states. The Conference consisted of ambassadors of Great Britain, Italy, and Japan accredited in Paris and the French minister of foreign affairs. The ambassador of the United States attended as an observer because the U.S. was not an official party to the Treaty of Versailles).

DIPLOMATIC DEVELOPMENTS

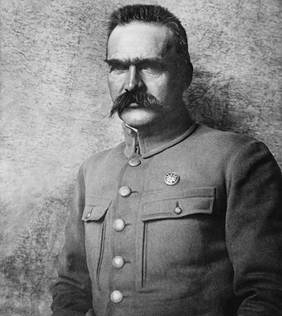

Poland did not recognize the independence of Lithuania as Polish leader Józef Piłsudski hoped to revive the old Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth and campaigned for some kind of Polish–Lithuanian union in the Paris Peace Conference. Poland also did not intend to make any territorial concessions, justifying its actions not only as part of a military campaign against the Soviets but also as the right of self-determination of local Poles. According to the 1897 Russian census, the disputed city of Vilnius had an ethnic breakdown of 30% Poles, 40% Jews, and 2% Lithuanians; however the percentage of Lithuanians was much higher in the surrounding countryside. According to the 1916 German census, Poles constituted 50% of city's population. The Lithuanians claimed Vilnius as their historical capital and refused any federation with Poland, desiring an independent Lithuanian state.

They regarded Polish federalism as recreation of Polish cultural and political dominance. The Lithuanian government in Kaunas, designated as the temporary capital, saw the Polish presence in Vilnius as an occupation. In addition to the Vilnius Region, the Suwałki Region was also disputed due to the fact it had a mixed Polish and Lithuanian population. In effect what Poland was saying was that if many Poles lived in an area, the area should be/is a part of Poland regardless of the fact that the area was in another country.

At the time the international situations of newly independent Poland and Lithuania were unequal. Poland, much larger in territory and population, was dedicated point 13 in Woodrow Wilson's Fourteen Points (The Fourteen Points was a speech given by United States President Woodrow Wilson to a joint session of Congress on January 8, 1918. The address was intended to assure the country that the Great War was being fought for a moral cause and for postwar peace in Europe. Point 13 was – “An independent Polish state should be erected which should include the territories inhabited by indisputably Polish populations, which should be assured a free and secure access to the sea, and whose political and economic independence and territorial integrity should be guaranteed by international covenant”).

Poland was recognized by all nations of the Entente, officially invited to the Paris Peace Conference and became one of the founding members of the League of Nations. Poland also enjoyed a close alliance with France. Lithuania did not receive international recognition (it was first recognized formally in July 1920 by Soviet Russia) as the Entente hoped to revive the Russian Empire within its former territory, which included Lithuania. Lithuania was not invited to any post-war diplomatic conferences. It also had to battle negative propaganda that the Council of Lithuania was a German puppet, that Lithuanians harbored pro-Bolshevik attitudes or that Lithuania was too small and weak to survive without a union with Poland.

MAY to SEPTEMBER 1919 – RISING TENSIONS

DEMARCATION LINES

Map of

demarcation lines of June 18 (light green) and July 26 (dark green) between

Poland and Lithuania. Poland ignored both lines and continued to advance up to

the orange line. Railroads are marked by black stitched lines.

The Conference of Ambassadors drew the first demarcation line on June 18. The line, drawn about 5 km (3.1 mi) west of the Warsaw – Saint Petersburg Railway, was based on the military situation on the ground at that time rather than ethnic composition. Neither Poles nor Lithuanians were content with the line. The Polish Ministry of Foreign Affairs rejected the line as it would require the Polish forces to retreat up to 35 km (22 mi). The Lithuanians protested leaving Vilnius and Hronda under Polish control. As German volunteers were departing from Lithuania and Lithuanian forces were preoccupied with battles against the Soviets in northern Lithuania, Poland mounted an offensive on a 100 km (62 mi) wide front moving 20–30 km (12–19 mi) deeper into the Lithuanian territory and Lithuania could not organize an effective defense to counteract this offensive.

Ferdinand Foch

On July 18, Ferdinand Foch proposed the second demarcation line, known as the Foch Line. It was approved by the Entente on July 26. The Lithuanians were informed about the new line only on August 3. Two major modifications favorable to the Poles were made: the Suwałki Region was assigned to Poland and the entire line was moved about 7 km (4.3 mi) west. Again, both Poles and Lithuanians protested the line as it would require them to withdraw their armies from the Vilnius and Suwałki Regions respectively. The German administration, which had not yet retreated from the Suwałki Region, also opposed the Foch Line. The new line did not immediately halt the hostilities. After a couple of Polish attacks on July 29 and August 2, the front stabilized.

THE SEJNY UPRISING

The Lithuanians obeyed the Foch Line and retreated from Suwałki on August 7, 1919. However, they stopped in ethnically mixed Sejny and formed a line on the Czarna Hancza river – Wigry Lake. They showed their intention to stay there permanently, which caused concern among the local Poles. On August 12, the Poles of that area organized a rally of about 100 people demanding incorporation into Poland. The Sejny branch of Polish Military Organization (PMO) began preparing for an uprising, scheduled for the night of August 22 to 23, 1919 and between 900 and 1,200 partisans joined PMO forces. On August 23, the Poles captured Sejny and attacked the towns of Lazdijai and Kapčiamiestis on the Lithuanian side of the Foch Line. The insurgents planned to march as far as Simnas (located 23 km west of Alytus). Lithuanians recaptured Sejny on August 25 for a few hours. On August 26, Polish regular forces – the 41st Infantry Regiment – joined the PMO volunteers. On September 5, the Lithuanians agreed to withdraw behind the Foch Line by September 7. Poland secured Sejny and repressed Lithuanian cultural life: the Sejny Priest Seminary was expelled, Lithuanian schools and cultural organizations closed. After the uprising, the mistrust of Poles prompted Lithuanian intelligence to intensify its investigations of Polish activities in Lithuania. This helped to detect and prevent a planned coup d'état in Kaunas to overthrow the government of Lithuania.

Polish cavalry parade

in Sejny

THE PLOISH COUP ATTEMPT

Sometime in mid-July 1919, PMO forces in Vilnius began planning a coup to replace the Lithuanian government with a pro-Polish cabinet, which would agree to a union with Poland of the proposed Miedzymorzr federation, also known as Intermarium was a plan, pursued by Polish leader Jozef Pilsudski, for a federation, under Poland's control of Central and Eastern European countries, invited to join the proposed federation were the Baltic states of Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia, Finland, Belarus, Ukraine, Hungary, Romania, Yugoslavia and Czechoslovalia. The proposed federation was meant to emulate the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, stretching from the Baltic Sea to the Black Sea that, from the end of the 16th century to the end of the 18th, had united the Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. Intermarium complemented Piłsudski's other geopolitical vision of Prometheism, whose goal was the dismemberment of the Russian Empire and that Empire's divestment of its territorial conquests into Polish control. Intermarium was, however, perceived by some Lithuanians as a threat to their newly established independence, and by some Ukrainians as a threat to their aspirations for independence and was opposed by most Western powers.

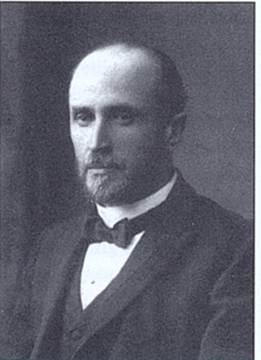

Leon Wasilewski

Polish leader Jozeph Pilsudski believed there were enough Polish sympathizers in Lithuania to carry out the coup. On August 3, a Polish diplomatic mission led by Leon Wasilewski, in Kaunas had a double purpose: propose a plebiscite (common people’s law) in the contested territories and assess preparedness for the coup. On August 6, the Lithuanian government rejected the plebiscite proposal, stating that the disputed territories constitute ethnographic Lithuania. PMO planned to capture and hold Kaunas for a few hours until arrival of the regular Polish troops, situated only some 40–50 km (25–31 mi) east from the city. The coup would be portrayed as an initiative of the local population to "free Lithuania from German influence" while denouncing any involvement of the Polish government. Polish newspapers ran a propaganda campaign claiming that the Council of Lithuania was simply a German puppet. The coup was initially scheduled for the night of August 27 to 28, but was postponed to September 1. Lithuanian intelligence discovered the coup, but did not have a list of PMO members. Lithuanian authorities began mass arrests of some 200 Polish activists, including some officers of the Lithuanian Army. Kaunas was declared under a state of siege. Polish press saw the mass arrests of Polish activists "to whom no charge can be ascribed other than being Poles" as proof of systematic anti-Polish policies of the German-ridden Lithuanian government”. PMO was little affected by the arrests and scheduled another coup attempt for the end of September. However, Lithuanians obtained a full PMO membership list and liquidated the organization in Lithuania.

SEPTEMBER 1919 to JUNE 1920 - MORE POLISH ATTACKS

After the failure of the coup in Kaunas there were numerous incidents. On September 19, 1919, Polish troops attacked Gelvonai and continued towards Ukmergė. On several occasions fights broke out regarding a strategically important bridge over the Šventoji River near Verpriai. In October, when the main Lithuanian forces were deployed against the Bermontians (The West Russian Volunteer Army or Bermontians was an army in the Baltic provinces of the former Russian Empire during the Russian Civil War of 1918-1920) in northwestern Lithuania, the attacks intensified and Poles captured Salakas on October 5 and attacked Kapčiamiestis on October 12. The front stabilized, but harassment of border guards and local villagers continued throughout late 1919 and early 1920. In March 1920, the Poles attacked along the railroad stations in Kalkūni and Turmantas. The situation was investigated by British and French observers and reported to the Entente. The situation somewhat improved only in late spring of 1920 when most Polish troops were deployed to Ukraine during the Polish–Soviet War.

At the time Lithuania faced a severe budget crisis – in 1919 its revenue was 72 million while expenses reached 190 million German marks. While the government was struggling to obtain financial assistance and loans, deep cuts affected the army. Instead of increasing its armed forces to 40,000 men, Lithuania was forced to cut them to about 25,000.

In part 2 of 4 - ADAVANCES and RETEATS

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

VilNews e-magazine is published in Vilnius, Lithuania. Editor-in-Chief: Mr. Aage Myhre. Inquires to the editors: editor@VilNews.com.

Code of Ethics: See Section 2 – about VilNews. VilNews is not responsible for content on external links/web pages.

HOW TO ADVERTISE IN VILNEWS.

All content is copyrighted © 2011. UAB ‘VilNews’.

Click on the buttons to open and read each of VilNews' 18 sub-sections

Click on the buttons to open and read each of VilNews' 18 sub-sections

Why didn't my comment get published? Is there censorship in Vilnews?

[…] Read more… […]

Thank you for the very interesting post. The demograpics in 1897 is provided here – http://demoscope.ru/weekly/ssp/rus_lan_97_uezd.ph…

Interestingly in the areas around Vilnius excluding the city ("Vilenskij ujezd bez goroda") Belarussians constituted around 87 000, Poles 25 000, Lithuanians 73 000, and Jews 15 000. So it was a very mixed area, and I wonder if "Belarussians" became "Poles" in later censuses.

[…] Read more… Category : Featured black / Front page […]