THE VOICE OF INTERNATIONAL LITHUANIA

|

VilNews has its own Google archive! Type a word in the above search box to find any article.

You can also follow us on Facebook. We have two different pages. Click to open and join.

|

The Polish-Lithuanian

War 1919-1920

Part 4 of 4 – The AFTERMATH

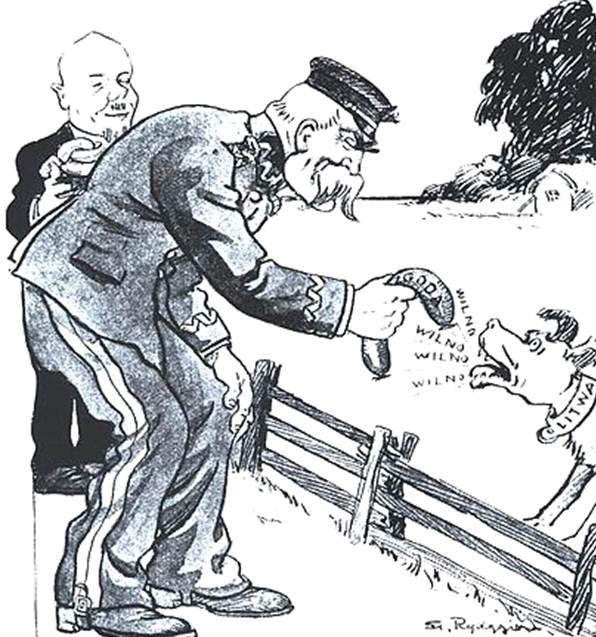

A satirical picture from interwar Polish press (around 1925-1935): a caricature of Marshal Józef Piłsudski and Lithuania, criticizing Lithuanian unwillingness to compromise over Vilnius region. Marshal Piłsudski offers the meat labeled "agreement" to the dog (with the collar labelled Lithuania); the dog barking "Wilno, wilno, wilno" replies: "Even if you were to give me Wilno, I would bark for Grodno and Białystok, because this is who I am."

Su pagarbe Vincas Karnila, Associate editor

vin.karnila@VilNews.com

In March 1921, the plans for a referendum vote were abandoned. Neither Lithuania, which was afraid of a negative result, nor Poland, which saw no reason to change status quo, wanted it. The parties could not agree in which territory to carry out the vote and how Żeligowski's forces should be replaced by the League's forces. The League of Nations then moved on from trying to solve the narrow territorial dispute in the Vilnius Region to shaping the fundamental relationship between Poland and Lithuania. During 1921, Belgian Paul Hymans suggested several Polish–Lithuanian federation models but all were rejected by both sides.

The general election in the (Polish) Republic of Central Lithuania was an election to the Vilnius Sejm (parliament) of the Polish-dominated Republic of Central Lithuania on January 8, 1922. The new parliament was intended to formally legalize incorporation of Central Lithuania into Poland. Such a measure was fiercely opposed by Lithuania, which claimed the territory for itself. The election was boycotted by non-Polish minorities and its results were unrecognized by the Lithuanian government in Kaunas and the League of Nations. The elected parliament convened in February 1922 and, as expected, voted to incorporate the Republic into Poland. Poland’s parliament accepted the resolution of the Diet and at the end of March 1922 Central Lithuania became Wilno Voivodeship of the Second Polish Republic. The League of Nations ended its efforts to mediate the dispute.

After Lithuania seized the Klaipėda Region, from Germany, in January 1923, the League saw recognition of Lithuanian interest in Klaipėda as adequate compensation for the loss of Vilnius. The League accepted the status quo in February 1923 by dividing the neutral zone and setting a demarcation line, which was recognized in March 1923 as the official Polish–Lithuanian border. Lithuania did not recognize this border.

The dispute over Vilnius remained one of the biggest foreign policy issues in Lithuania and Poland. Lithuania broke off all diplomatic relations with Poland and refused any actions that would recognize Poland's control of Vilnius even de facto. For example, Lithuania broke off diplomatic relations with the Holy See after the Concordat of 1925 established an ecclesiastical province in Wilno thereby acknowledging Poland's claims to the city. Poland refused to formally recognize the existence of any dispute regarding the region, since that would have lent legitimacy to the Lithuanian claims. Railroad traffic and telegraph lines could not cross the border, and mail service was complicated. For example, a letter from Poland to Lithuania needed to be sent to a neutral country, repackaged in a new envelope to remove any Polish signs, and only then delivered to Lithuania. Despite several attempts to normalize the relations, the situation of "no war, no peace" lasted until Poland demanded to reestablish diplomatic relations by issuing the ultimatum of 1938.

|

“Independent Lithuania cannot exist by itself” In April, 1918 Pope Bededict XV appointed Archbishop Achilles Ratti (later Pope Pius XI) as apostolic visitator to Poland and “ex Russian countries”, including Lithuania. Lithuanian – Polish relations became especially tense because of incorporation of Vilnius region into Poland. In 1921 apostolic visitator and delegate Rev. Antonio Zechini arrived in Kaunas. He publicly expressed the opinion that independent Lithuania could not exist by itself. Msgr. Zechini counseled Lithuanians to unite with Poles as they had done previously. On November 10, 1922 Vatican recognized independent Lithuania de jure. After the death of Pope Benedict XV Msgr. Antonio Zechini became Archbishop and apostolic delegate for the three Baltic nations. He did not favor the idea of a separate Lithuanian ecclesiastical province. On February 10, 1925 the Concordat was concluded between the Holy See and Poland. The Vilnius (Wilna) question was of the utmost importance to Lithuanians. The Polish Concordat did not undertake to decide the issue of territorial boundaries between Poland and Lithuania, but merely recognized a political de facto situation. Vilnius (Wilna), the ancient Lithuanian capital, was raised to the rank of archdiocese and made one of the five Polish ecclesiastical provinces. Polish Concordat caused great dissatisfaction among Lithuanian population. The situation became so acute that Archbishop Zechini departed for Riga without obtaining permission to return. The tempest was heightened by the news that Lithuanian bishop of Vilnius Jurgis Matulaitis (beatified 1987 by Pope John Paul II; Polish transcription: Jerzy Matulewicz) was forced to leave his See and departed for Rome.

|

In April, 1918 Pope Bededict XV appointed Archbishop Achilles Ratti (later Pope Pius XI) as apostolic visitator to Poland and “ex Russian countries”, including Lithuania. In 1921 apostolic visitator and delegate Rev. Antonio Zechini arrived in Kaunas. He publicly expressed the opinion that independent Lithuania could not exist by itself. Lithuania broke off diplomatic relations with the Holy See after the Concordat of 1925 established an ecclesiastical province in Wilno thereby acknowledging Poland's claims to the city. |

1938 POLISH ULTIMATUM to LITHUANIA

The 1938 Polish Ultimatum to Lithuania was an ultimatum delivered to Lithuania by Poland on March 17, 1938. The Lithuanian government had steadfastly refused to have any diplomatic relations with Poland after 1920, protesting the annexation by Poland of the Vilnius Region. As pre-World War II tensions in Europe intensified, Poland perceived the need to secure its northern borders. Five days earlier, Poland, feeling supported by international recognition of the annexation of Austria by Nazi Germany, decided it was imperative to deliver an ultimatum to Lithuania. The ultimatum demanded that the Lithuanian government unconditionally agree to establish diplomatic relations with Warsaw within 48 hours, and that the terms be finalized before March 31. The establishment of diplomatic relations would mean a de facto renunciation of Lithuanian claims to the region containing its historic capital, Vilnius (known in Polish as Wilno). Lithuania, preferring peace to war, accepted the ultimatum on March 19. Although diplomatic relations were established as a result of the ultimatum, Lithuania did not agree to recognize, in a legal sense or otherwise, the loss of Vilnius. The government of Poland made a similar move against the Czechoslovakian government in Prague on September 30, 1938, when it took advantage of the Sudeten Crisis, created by Nazi Germany, to demand a portion of and later annex Zaolzie. On both occasions, Poland used the international crises to address long-standing border disputes and to counter Germany's foreign policy initiatives.

INITIAL VERSION

The first version of the ultimatum, as drafted by Edward Rydz-Śmigły, Prime Minister Felicjan Slawoj Skladkowski, and Jan Szembek, contained six demands.

Edward Rydz-Śmigły Felicjan Slawoj Skladkowski Jan Szembek

1. Establish normal diplomatic and consular relations with Poland

2. Allow normal railway and road traffic and direct telephone and telegraph lines across the demarcation line

3. Amend the Lithuanian constitution to acknowledge that Vilnius was no longer the capital of Lithuania

4. Conclude the convention protecting the rights of the Polish minority in Lithuania in full

5. Conclude a trade and tariff agreement

6. Fully investigate the incident in Trasnykai

The Polish Foreign Minister Józef Beck, who had just returned from a trip to Sorrento, called for a government meeting on the night of March 16. During the meeting he argued that the ultimatum needed to contain only one demand - The establishment of diplomatic relations. In his view, such an ultimatum would not have violated any genuine Lithuanian interests and would offer much improved prospects for a peaceful resolution of the conflict and a speedy relief of tensions. It was in accordance with Beck's vision for Eastern Europe, which was based on a Warsaw dominated Polish–Baltic–Scandinavian bloc free of Soviet or German influence, a modified version of Jozef Pilsudski’s Miedzymorze plan, which required the normalization of relations with Lithuania. The removal of the other demands also reflected political pressure on Poland from the Soviet Union, France, and the United Kingdom to prevent the conflict from escalating into warfare.

The Polish government agreed to Beck's proposal and the ultimatum was toned down. However, at the same time, Beck ordered military preparations. Poland assembled four divisions along the demarcation line which totaled about 50,000 Polish troops compared to just over 20,000 Lithuanian troops. The Polish troops were reinforced by armored vehicles, by two air force regiments consisting of about one hundred aircraft and by the Polish fleet in the waters of the Baltic Sea along the Lithuanian shore.

THE ULTIMATUM

The final text of the ultimatum, completed by Józef Beck and delivered through a Polish envoy in Tallinn to Bronius Dailidė, the Lithuanian ambassador in Estonia, was as follows:

1. "The proposition of the Lithuanian Government of March 14 cannot be accepted for it does not give sufficient guarantees concerning the security of the frontier in view of the negative results of all Polish–Lithuanian negotiations made up to the present time."

2. "For this reason the Polish Government declares that it considers as the only solution corresponding to the gravity of the situation the immediate establishment of normal diplomatic relations without any previous condition. This is the only way to regulate the neighborly questions for a Government animated by good faith to avoid events dangerous to peace."

3. "The Polish Government allows the Lithuanian Government 48 hours from the moment the note is presented for the acceptance of this proposition in making it known that diplomatic representations at Kaunas and Warsaw will be accredited not later than March 31 of this year. Until that date all discussions of a technical or other character between the Polish and Lithuanian Governments shall be continued by the envoys extraordinary and ministers plenipotentiary at Tallinn.

The exchange of notes attached concerning the establishment of diplomatic relations shall take place, before the expiration of the period of 48 hours mentioned, at Tallinn between the Polish and Lithuanian Ministers at Tallinn."

4. "The proposition above mentioned will not be the subject of discussion with regard to its content or form—it is an unchangeable proposition.

The failure to respond or the presentation of any supplements or reservations shall be considered by the Polish Government as a refusal. In the event of a negative reply the Polish Government will guarantee the just interest of the state by its proper means."

The ultimatum contained an attachment which was a draft of what would be deemed an acceptable response to the ultimatum. The proposed response stated only that Lithuania agreed to establish regular diplomatic relations, send a legation to Warsaw, and guarantee normal conditions of operation for a Polish legation in Kaunas.

These tensions were one of the reasons why Jozef Pilsudski’s Miedzymorze planed federation was never formed. Ultimately the Soviet Union returned Vilnius to Lithuania after the Soviet invasion of Eastern Poland in September 1939.

IN RETROSPECT

Historians have speculated that if was it not for Poland’s involvement in the Polish-Soviet War, Lithuania would have been invaded by the Soviets and would never have experienced two decades of independence despite the Soviet-Lithuanian Treaty of 1920. Other historians have countered that due to countries such as Latvia and Lithuania engaging in their own wars against the Soviets, during this time period, it resulted in Poland not having to deal with the might of the entire Soviet force which, helped in their success repelling the Soviet’s invasion.

It is felt by many that the Russian hostilities in this area of Europe, at this time, set the stage for the diplomatic efforts of Poland and Lithuania, to resolve their issues, to break down and escalate into open warfare. While what would have happened if Lithuania and Poland were not involved in open warfare with the Russia will never be known. Personally I would like to believe that if peace had been in the area, the two neighbors would have found some peaceful way to work things out between them. In looking back at this time in history I find it very sad that two countries that had such a strong bond between them for hundreds of years would ultimately find themselves at war with each other. It is especially sad since it was the bond between these two countries that help keep peace in this area for hundreds of years. If you attacked Poland you had to be prepared to also take on Lithuania. If you attacked Lithuania you had to be prepared to also take on Poland. This was something a prospective enemy had to contend with and this bond of two friends most likely discouraged many a hostile force from embarking on any campaign to break the peace in this area. This is why the Polish – Lithuanian War is a very sad part of history for both countries. Two friends that once supported, defended and protected each other were now at war with each other – Very sad indeed.

The dispute over the borders of the two countries is something to be considered and both countries believed that they had just cause to contest this issue. During the period of the Polish–Lithuanian union from 1385 until 1569 and then the period of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth from 1569 until 1795, the borders of the two neighbors were clearly defined and for the most part remained intact. There was a very definite line that identified where the Polish land was and where the Lithuanian land was and both sides seemed quite happy with this.

This unfortunately all came to an end in 1795. What now began was the period of Lithuania and Poland being carved up, sliced up and divided up by a long list of larger and more powerful countries. This ongoing rearranging of the Polish/Lithuanian border continued from 1795 to post World War I. Without going into all the fine detail of whose pre 1795 land was now within whose border, I’m sure you can imagine what a complete mess this was and what kind of challenge it would have been to restore the border to where it was in 1795.

The pre 1795 Polish/Lithuanian border compared with the border as it was at the end of World War I gave both sides with a very difficult situation to resolve and as I have said before, both sides felt that they had very justifiable claims. Aside from the contested cities, towns and villages in the pre 1795 border area there is one point of contention that, I must admit, I have had a very difficult time of understanding and making any justifiable sense of for many of year. This is in regards to Vilnius and the Vilnius area. Ever since there was a Poland and ever since there was a Lithuania and ever since there was a Vilnius and ever since there was a Polish/Lithuanian border, Vilnius and the Vilnius area had always been well within the boundaries of Lithuania.

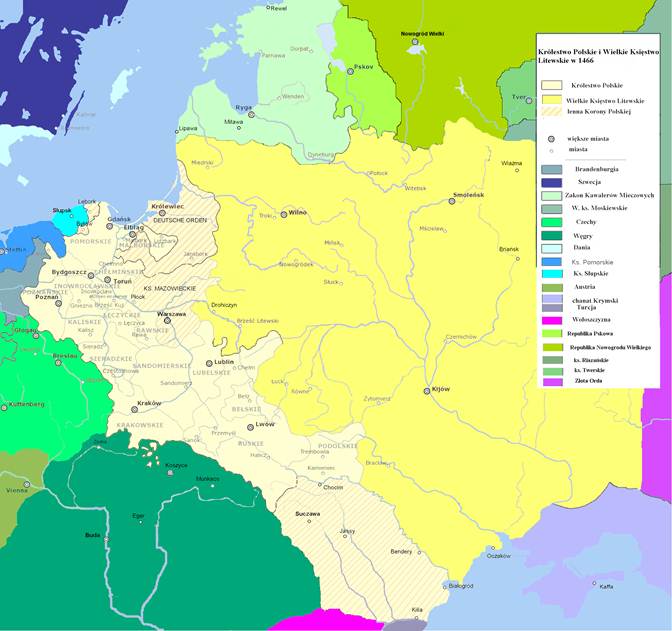

Polish–Lithuanian union 1466.

When countries are at war with each other, capturing and occupying their opponent’s capital is most always a prime objective. In this regard I can fully understand Poland’s efforts to capture Vilnius. What I have had a very difficult time of understanding and making any justifiable sense of for many of year is Poland’s reasoning as justification in not only capturing Vilnius but also occupying it for twenty years. In anything I have ever read or heard regarding this, the only point of reasoning I have ever been able to decipher is that since there was a large percentage of the Vilnius population that were Polish citizens or of Polish nationality then this meant that Vilnius belonged to Poland. Not only with Vilnius but in many other towns and villages that had been within the pre 1795 border of Lithuania, Poland’s claim as to why these towns and villages should be a part of Poland was that there was a large percentage of the population that were Polish citizens or of Polish nationality.

Map showing the greatest extent of the borders of both Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania,

The Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth.

KIND OF SAD ISN’T IT?

Now some might say that the only reason I have a difficult time of understanding and accepting this logic is because I am Lithuanian. To these people I would have to respectfully disagree. It is not about a Lithuanian – Polish issue. It is an issue about honoring the sovereignty of another country. I am not from Estonia but I would react with great shock and emotion if one day Russia announced that they were going to invade and annex the north-eastern part of Estonia and try to justify it by saying it is because there are many Russian citizens and people of Russian nationality live in this area. I would react with the same shock and emotion if Russia announced that they were going to invade and annex all of Latvia and try to justify this by citing not only how many people of Russian nationality live there but also how many people speak Russian there as their first language. I could go on and on with this logic. If this was an issue that was simply a part of history and had been long since resolved and forgotten about perhaps I would not still be trying ever so desperately to understand the logic but to this day there are people that will look you right in the eye and say that Vilnius is a part of Poland.

Assembling all the information for this series of articles was interesting but I must also say a bit depressing. This is sad a story about two friends being at war with each other. The Polish – Lithuanian bond of 1385 to 1795 was one of the, if not the, longest bonds of friendship in all of Europe. This bond also resulted in one of the greatest forces in all the history of Europe, something that undoubtedly resulted in many years of peace in this area.

As you all know, there are still issues between the two friends. While some of these issues are quite serious, to the extent that the EU has needed to step in and referee, some of these issues are not that serious but there are people out there that like to throw these smaller issues in with the big ones just to make the big issues even MORE serious. Personally it is my greatest hope that these issues can be resolved – SOON!!! It would be nice to get the two friends back together again and they would both be much better for it and the EU would be better for it.

One final thought – Often when I am in Druskininkai (one of my favorite places), since of its close proximity to Poland, I often end up talking with some people visiting from Poland. Trying to always be somewhat of a friendly person I’ll usually offer up a greeting or some pleasantry and since Druskinikai has a warm and friendly atmosphere about it this often results in a pleasant conversation. Since I speak very little Polish and often they speak very little Lithuanian, if they speak English we are able to have a very nice extended conversation - Even if they don’t speak English we both do everything we can to communicate and exchange pleasantries. After these very pleasant conversations, no matter how long or how short, I always wonder why it is that a Lithuanian and some people from Poland, who are perfect strangers to each other, can sit down and have such a warm and friendly conversation but our two countries are having such a difficult time getting along???

But, I guess that’s how things have always been and perhaps always will be with the peoples of many countries –

Kind of sad isn’t it?

Su pagarbe and Dziękujemy i pozdrawiamy

Vincas Karnila

Associate editor

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

VilNews e-magazine is published in Vilnius, Lithuania. Editor-in-Chief: Mr. Aage Myhre. Inquires to the editors: editor@VilNews.com.

Code of Ethics: See Section 2 – about VilNews. VilNews is not responsible for content on external links/web pages.

HOW TO ADVERTISE IN VILNEWS.

All content is copyrighted © 2011. UAB ‘VilNews’.

Click on the buttons to open and read each of VilNews' 18 sub-sections

Click on the buttons to open and read each of VilNews' 18 sub-sections

I did post a comment but it appeared to have been censored out.

[…] Read more… Category : Front page […]

[…] Read more… Category : Historical Lithuania […]

[…] READ TODAY’S ARTICLE – PART 4 OF 4 […]