THE VOICE OF INTERNATIONAL LITHUANIA

|

VilNews has its own Google archive! Type a word in the above search box to find any article.

You can also follow us on Facebook. We have two different pages. Click to open and join.

|

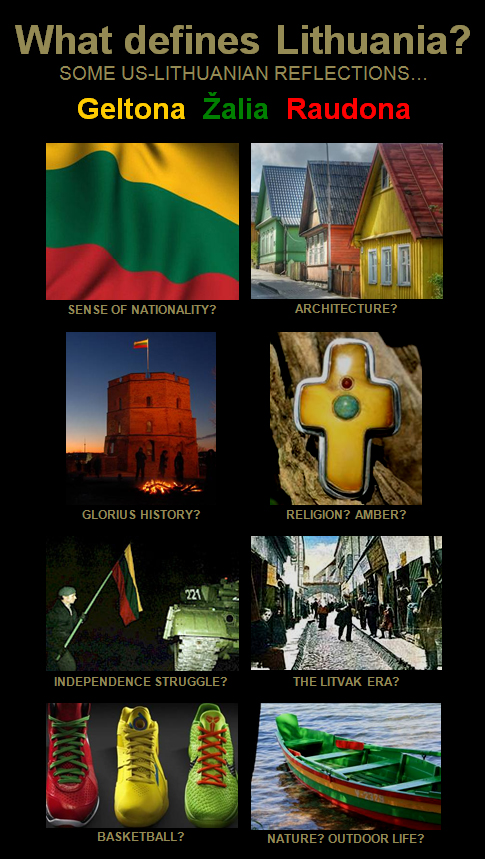

By Jennifer Virškus

A nation can be defined by several different characteristics; geographical location, language, a common history, cultural body, or race. The Lithuanian nation is defined by all of these. Lithuania has a language which is unique in the world and a culture that runs deep. It shares more than two centuries of its history with Poland, and few other nations have survived occupation by so many different groups. There are several types of nationalism; primordial, civic, organic, and liberal. Because of the lack of opportunity in Lithuania, young Lithuanians have recently tried to convince themselves that they want to “forget” their Lithuanian culture and move on to a new life in the West, but it is not possible. Lithuanians will always be Lithuanians whether they are in Lietuva or not. This is evident in the Lithuanian-American community, though they are clearly Americans, their Lithuanian identity stays with them. This is because Lithuanian nationalism is both geographic and organic, an entity to which all Lithuanians belong, as parts of a whole and independently of their will, choice or consciousness.

To be clear, I must define what I mean by geographic and organic nationalism. Geographic nationalism is a combination of primordial and social construct nationalism. That is to say, it is based on an ethnic identity and linked to a territory (O'Laughlin). It is distinctive, based on a unique culture, religion, and literature. At the same time, geographic nationalism is constructed by the elites, though not necessarily for their own benefit. In the case of Lithuania, it was constructed and propagated out of a feeling of repression, and the desire of the people to live in a democratic state they could call their own. Johann Gottfried Herder used the term nationalism while applying it to Volk, emphasizing the organic nature of a people. This goes beyond the primordial definition to suggest that nationalism is something ingrained in a people. Herder says that the nation is a natural creation and nationalities are not the product of men, rather the “work of a living organic force that animates the universe.” National culture is, as Herder puts it, closed to foreign eyes (Viroli). So, Lithuanian nationalism is primordial in the sense that it is based on an ethnic identity, language, and culture; it is socially constructed, or rather promoted, by the elite who want to form a Lithuanian state, and organic in that birth is the only way for one to become Lithuanian.

The Lithuanian state was founded in the 13th century by Grand Duke Mindaugas. Lithuania began to expand in the 14th century, and by the beginning of the 15th century Lithuania was one of the largest countries in Europe

FIGURE 1: The map of Lithuania in the 13th-15th centuries.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Lithuanian_state_in_13-15th_centuries.png

In 1569 Lithuania and Poland formed the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, ruled by an elected king who was also Grand Duke of Lithuania. During the partitions of Poland, Lithuania was largely annexed by the Russian Empire, disappearing from the map completely (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2: Lithuanian borders from the 13th century to today.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:LithuaniaHistory.png

Germany occupied Lithuania during the First World War until the Lithuanians declared independence on 16 February 1918. The Lithuanian Republic was proclaimed later that year and enjoyed a brief period of independence between the two World Wars. Independence lasted barely 20 years as the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact of 1939 allowed the USSR to take control of Lithuania. The Lithuanian Soviet Socialist Republic was proclaimed on 21 July 1940. The Germans occupied Lithuania again from 1941-1944. The Red Army returned in 1944, deporting mass numbers of Lithuanians to Siberia. Small groups of anti-Soviet activists continued to resist until 1952, though, all political parties were disbanded and the country was ruled exclusively by the Lithuanian Communist Party. Gorbechev’s policy of glasnost during the 1980’s allowed Lithuanian nationalism—kept alive by underground and exile groups—to resurface in the reformist climate. Sajudis, the Lithuanian Movement for Reconstruction, was established in 1988. On 11 March 1990, Vytautas Landsbergis declared the independence of Lithuania from the Soviet Union. After a military intervention and a bloody attempt by the Soviets to reclaim the Vilnius TV Tower, the USSR council also recognized the independence of Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia. Today, Lithuania is a republic-parliamentary democracy, with Dalia Grybauskaitė serving as President and Head of State

FIGURE 3: Lithuania today.

To choose one event in which Lithuanian nationalism originated is impossible. Rather, it was the combination of so many centuries of repression which gradually built nationalism to its current strength. We can, however, establish the roots of Lithuanian nationalism, but to do so, we must first establish national identity by looking at Lithuania’s historical foundations that have lasting ethnic bonds and language, which in turn reflect self-identification. “Heroic” self-perceptions are shaped by the collective memory of the strength of the Grand Duchy (Kavolis 1991). Certainly, the fight for independence from Russia and then Germany during the First World War—and most recently, from the Soviet Union—play a major role. It is often the repression of a nation which becomes a rallying point for nationalism; this is certainly true in the case of Lithuania. Modern national identity is also encouraged by contemporary social and political changes. The opportunity to separate from the Soviet Union and the risk-taking courage of the Lithuanians has not only helped to transform Lithuania, but also re-enforced their own national identity. Lithuanians can take pride in the fact that their provincial struggle gained the attention of the world and paved the way for many other nations on the road to independence.

The role of language, religion, monuments, and music cannot be underestimated in determining the origin of nationalism in Lithuania. The Lithuanian language draws its roots from Sanskrit. It is historically and linguistically important since it retains most of its archaic Indo-European forms. This is due to the fact that during the Polish-Lithuanian dynasty, Polish was the preferred tongue, and during Russian occupation a policy of “russificaiton” insisted that Russian be used in daily life. Though the underground journal, Aušra (the Dawn), created by Jonas Basnavičius, brought the Lithuanian language en vogue among Lithuanian intellectuals, the language developed little until the first Lithuanian independence of 1918 when it could finally be spoken openly. The language quickly became a strong source of pride as more and more Lithuanians began to learn and speak the language. John Locke describes Lithuanian national identity as “national language and self-dedication.” In his autobiography, Lithuania Independent Again, former Lithuanian president, Vytautas Landsbergis, reflects on the lives of his grandfathers, Gabrielius Landsbergis and Jonas Jablonskis, who worked together on the staff of Vilniaus Žinios (The Vilnius News), the only legal publication in the Lithuanian language at the turn of the century. Gabrielius’ family had been polonized and he only began to learn Lithuanian after entering high school. As he embraced the language, he became “firm and enthusiastic in his belief that he was a Lithuanian” (Landsbergis 2000). The growing nationalist movement was solidified as the geographical region of Lithuania was defined by its language. Aušra is an instance in which the elite was attempting to construct Lithuanian nationalism to inspire a move toward independence, however in doing so, led many Lithuanians to discover and embrace their language and the ethnic identity that accompanied it, having a lasting effect on nationalism today.

In addition to inspiring the use of the Lithuanian language, Aušra, is also considered the organ of Catholic Nationalism (Welch). The Polish-Lithuanian Dynasty was surrounded by Lutheranism to the West and North, and Russian Orthodoxy to the East. Together with the language, the Catholic faith became something that set the Lithuanians apart from their neighbors. National independence was the long-term goal, but Aušra rejected revolutionary activity, concentrating on preserving a nationally conscious and morally strong people, which it said was a precondition for statehood. It proposed a state similar to Israel where citizenship is based on the primordial elements of Lithuanian nationality and the Catholic religion (Welch 1983). Catholicism became so intertwined with Lithuanian identity, that during the interwar years to be Lithuanian was to be Roman Catholic (Donskis 2002). Here we have an example of nationalism being tied to an element already ingrained in Lithuanian society. Lithuanians were already Catholic, what changed in the first part of the twentieth century is that suddenly being Catholic, and Lithuanian, was something to be proud of.

FIGURE 4: Kryžiu Kalnas (the Hill of Crosses), near Šiauliai.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Hill-of-crosses-siauliai.jpg

Many monuments in Lithuania that promote nationalism have been created out of ties to the Catholic church. Most notably, Kryžiu Kalnas (the Hill of Crosses), near Šiauliai. A Lithuania pilgrimage center, Kryžiu Kalnas is a small hill where many hundreds of thousands of crosses have been placed to represent Christian devotion and as a memorial to Lithuanian national identity. This monument dates to the 14th century and is an example of peaceful resistance to oppression. Soviet tanks tried to destroy it on three separate occasions, leveling the monument during the night and either burning the crosses or turning them into scrap metal. Each time, crosses reappeared within days. Today it is an international pilgrimage site of mystical proportions, home to hundreds of thousands of crosses.

One can also think of the Lithuanian flag (Figure 5) as a monument to the Lithuanians who fought and died for the freedom of their country. The flag, adopted on 19 April 1918, consists of three horizontal stripes of yellow, green and red, the three colors most used in traditional weaving. The yellow represents the fertile fields of Lithuania, golden with ripe rye, wheat and flax. The green is a symbol of the nation’s vitality, and the red is a monument to the blood shed in defending the freedom of the homeland (Blavasciunas). All the elements of Lithuanian nationalism are represented in the flag: the organic yellow and green of the life that continues to grow, social construct references to the blood shed—a rallying point which the elites can use to promote nationalism—and the primordial element of the traditional colors used.

FIGURE 5: The Lithuanian flag.

Like monuments, music plays an important role in the expression of Lithuanian nationalism, most importantly, the work of Mikalojus Konstantinas Čiurlionis. Čiurlionis worked at the end of the 19th century helping to spawn nationalism with his symphonic poems which speak of the beauty of Lietuva. His two most important works, Jūra (The Sea) and Miške (The Forest) describe the two most prominent features of Lithuanian geography. The sea was an important resource for Amber as well as being valuable for trade with Scandinavia and Western Europe. The forest was the setting of most of Lithuanian folklore and pagan traditions, which are still practiced today. Čiurlionis’s work is a musical illustration of ancient ritual, religious devotion and national nostalgia, tying Lithuanian national identity directly to the land.

The national anthem (Figure 6) written by Dr. Vincas Kudirka contains references not only to national themes, but also to “the paths of virtue” (Kavolis). Kudirka did not intend for his poem, “Tautos Hymnas” (“National Hymn”), which espoused a love for Lithuania, to become the national anthem (Blavasciunas), yet it also includes all the elements of the origin of Lithuanian nationalism already mentioned above. The first line, “Lietuva, tėvyne mūsų, tu didvyrių žeme!” (“Lithuania, my homeland, land of heroes!”) makes the geographical connection, while the rest of the poem goes on to glorify Lithuania’s history and virtue. It does not mention revolution; on the contrary, it speaks only of the moral good of the Lithuanian people who have “light and truth” guiding their steps. These are certainly primordial elements; they come straight out of historical Lithuanian culture and values. The anthem is organic as it refers to Lithuania’s “children” working for the good of their native land. This implies the land upon which they were born—going back to Herder's argument that national identity is correlated to one’s birthplace—is integral to their identity.

During the Soviet Occupation, attempts to unite the USSR meant not only “russificaiton” but the outright banning of everything Lithuania had to be proud of; the language, Catholicism, music—in particular folk music—and public celebration of national festivals. Many monuments were destroyed and churches were turned into science museums. Hélène Carrère d'Encausse asks the question in her book Decline of an Empire, “Has the Marxist ideology of human uniformity gained mastery over this diverse society in which for the first time in history it has taken root and come to power?” Soviet indoctrination had several effects. The older generation that had seen the capabilities of the Soviets were sufficiently scared to live quietly, not wanting to risk deportation. Small children were the easiest to indoctrinate, and many went on to join the Komsomol (Soviet Young Communist League). There was however a small group of students, particularly at the time of Stalin’s death, who were eager to rediscover the outside world and their own heritage. Vytautas Landsbergis belongs to this group, and he was fortunate enough to study under Jadvyga Čiurlionytė, sister to Čiurlionis. She had established, by her own efforts, a department of Lithuanian folk music at the Vilnius Conservatoire (Landsbergis 2000). Landsbergis went on to become an expert in the music of Čiurlionis, writing several books on his painting and music. Together with the work of Čiurlionis’s sister, Landsbergis was the founder of a revival in Lithuanian Nationalism in the 1950’s, inspiring his own generation, and generations to follow to the idea that Lithuania was something to be proud of, and worth defending.

Opposition to the Soviet regime in Lithuania stems mainly from national and religious sentiments (Welch); of course the two are directly related. As a response to the Soviet secularization of society, a religious movement was spawned based on the overtly religious society which existed before the occupation. Many who were categorized as “non-believers” during Soviet times were actually secret practitioners. Religion became a personally and privately expressed, rather than institutionally expressed, experience. The Catholic rights movement evolved to be a comprehensive campaign against secularization (Welch) which was aided by the visit of Pope John Paul II to Poland in 1979, a visit that deeply disturbed communist authorities across the Eastern Bloc. The Catholic church was in a better position to publicly promote a nationalist movement than a small group of individuals such as the one Landsbergis belonged to as the Soviets could not send the entire church to the Gulag. In her article, “Nationalism and Lithuanian Dissent”, Irene Welch discusses in depth the ethnographic clubs and underground publications such as Varpas (The Bell) and Laisvės Šauklys (The Herald of Freedom), which were part of the cultural movement that inspired attempts from underground political organizations such as the Lithuanian Revolutionary Liberation Front. These movements demanded a more aggressive opposition than the Catholic movement did. They were involved, like Landsbergis, in a rediscovery and preservation of the primordial elements of Lithuanian nationalism which had been attacked by the Communist Party and the KGB. Nationalism never died in Lithuania, but it is fair to say that it was difficult to express publicly.

A study was done in the early 1980's about the retention of nationalism in second generation Lithuanian-Americans/Canadians in Chicago and Montreal (Figure 7). It found that there was a significant retention of culture and nationalism among young adults in their twenties. In his article, Virga Jelionis wrote that in identity formation, an individual draws both from the collective and self-identity. Jelionis proves that Lithuanian-Americans/Canadians draw not from the collective identity of either America or Canada, but rather from their Lithuanian heritage, and their own self-identity is not American or Canadian, but Lithuanian. The study is interesting because in Chicago, there is an established and definite neighborhood where most Lithuanians live and socialize, no doubt contributing to their own retention of culture, however, in Montreal where we see the same cultural trends, no such neighborhood exists. This shows us that retention of Lithuanian nationalism is deeper, not simply constructed through daily exposure. It is something that a person is born with, and cannot escape. Not only do we see that Lithuanian-Americans/Canadians are proud and comfortable in their ethnic community, but they prefer to engage in social activities with other Lithuanians and are very interested and concerned in the future of their homeland. In addition, the study shows that second generation Lithuanians still feel strongly that their own children attend Saturday school[1] and speak Lithuanian at home. While Lithuanian nationalism is based on primordial elements, Saturday school, scout groups, and dance troupes are ways in which nationalism is socially constructed and promoted. What is interesting and important to note, is that Lithuanian nationalism, at least in expatriate communities, is being constructed by the masses, both individually and collectively, rather than an educated elite. Nearly 90% of respondents answered either “yes” or “sometimes” to the question, “I am very conscious of, or preoccupied with, my [Lithuanian] nationality.” Very simply, Lithuanian nationalism, and being Lithuanian is important.

Nationalism in Lithuania today, is a very open experience, though, participation in Catholic activities is significantly lower. Communism succeeded in wiping out religious identity in the current twenty-something generation. This was the last generation born under the Soviet regime, and the current widespread trend away from the church in Europe also contributes. In 1991, there was no organized culture, and there was some debate about the path Lithuania should follow; join the pluralistic West, reaffirm certitudes of Lithuania’s own past, or seek to create a more universal post-totalitarian culture (Kavolis). One trend concerns the belief that individuals begin as members of a nation and that its leaders are "indistinguishable" from the nation, as the Lithuanian Democratic Party declared about Vytautas Landsbergis (Kavolis). It would seem that Lithuania is leaning toward reaffirming “certitudes of Lithuania’s past;” we see nearly daily celebrations of “memorial days, numerous re-inaugurations of destroyed monuments, reburials of exhumed bodies of Siberian deportees—expressions of the ancient belief that a person ultimately belongs to his or her native soil” (Kavolis). Kryžiu Kalnas is covered with more crosses than ever, and new statues are being erected constantly in honor of Lithuania’s children, fallen in her defense. The brave men and women who stood up to the tanks of the Red Army during the attempted capture of the Vilnius TV tower were given Lithuania’s highest Medal of Honor. Shortly after independence was declared, an important statue of Lenin was taken down to be replaced with that of a famous Lithuanian personality, Frank Zappa. Lithuanians can finally be openly and publicly proud of whom they are, where they come from, and the language they speak.

I consider myself a Lithuanian nationalist, though my heritage is only half Lithuanian and my upbringing was much more American than ethnic Lithuanian. We ate kugėlis and babka on Christmas morning, had Easter eggs my Grandmother painstakingly decorated with beeswax and natural dyes every year, and went to a Lithuanian church once in a while. But I didn’t speak Lithuanian, or go to Saturday school, nor did I attend summer heritage camp at Dainava. My exposure to Lithuanian culture was more subtle—my Grandmother’s accent, a word here or there. Sometimes my Dėdė[2] Balys would ask my brothers and I for clothes or old toys to send to “the cousins” in Lithuania. I didn’t know what it meant to be Lithuanian, but I knew it was something I belonged to and something I was proud of. My first public exhibition of nationalism came when I was twelve. I bought a pin representing the American and Lithuanian flags flying together. This was in 1989, and there was a stir in the Lithuanian community that soon Lietuva would be independent again. My nationalism was not constructed—it was hardly encouraged—it is primordial, based on a culture I still know so little about, and it is organic, something I was born with, and something that will continue to grow with me. Today Lietuva is independent, and going there means going home.

Bibliography

Carrère d'Encausse, Hélène. Decline of an Empire. HarperCollins, 1981.

Dobryninas, Aleksandras. “The Paradoxes of Freedom in Search of their Roots and Fruits.” Lituanus 39 no.4, (1993).

Donskis, Leonidas. Identity and Freedom: Mapping nationalism and social criticism in twentieth-century Lithuania. London: Routledge, 2002.

Hartman, Gary. “The Origins and Growth of Baltic Nationalism as a Force for Independence.” Lituanus 38 no. 3 (1992).

Jelionis, Virga. “Ethnic Identification: A Study of Second-Generation Lithuanians’ Retention of Culture.” Lituanus 28 no. 3 (1982).

Kavolis, Vytautas. “The Second Lithuanian Revival: Culture as Performance.” Lituanus 37 no.2 (1991).

Landsbergis, Vytautas. Lithuania Independent Again: The Autobiography of Vytautas Landsbergis. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2000.

O'Laughlin, John. GEOG 4712 “Politcal Geography.” University of Colorado at Boulder, 2002.

Ramunas Personal Pages. http://www2.omnitel.net/ramunas/Lietuva/

Taylor, Peter J. and Colin Flint. Political Geography. Essex: Pearson Education Limited, 2000.

Valentiejus, Algis. “Early Lithuanian nationalism: sources of its legitimate meanings in an environment of shifting boundaries.” Nations and Nationalism 8 no. 3 (2002): 315–33.

Welch, Irene. “Nationalism and Lithuanian Dissent” Lituanus 29 no.1 (1983).

|

Jennifer Virškus

|

|

Figure 6

Lithuania, my homeland, land of heroes!

Let your Sons draw strength from the past.

Let your children follow only the paths of virtue,

working for the good of their native land and for all mankind.

Let the sun banish all darkness from Lithuania,

with light and truth always guiding our steps.

Let the love of Lithuania burn in our hearts

and for the sake of our country let unity blossom.

Figure 7

LITUANUS

LITHUANIAN QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES

Volume 28, No.3 - Fall 1982

Editor of this issue: Antanas Klimas

ISSN 0024-5089

Copyright © 1982 LITUANUS Foundation, Inc.

ETHNIC IDENTIFICATION:

A STUDY OF SECOND-GENERATION LITHUANIANS' RETENTION OF CULTURE

VIRGA JELIONIS

Hofstra University

1-Strongly Agree 5-Strongly Disagree

Having a recognized place in my ethnic community is important to me.

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

|

|

__________________________________________________________________________________ |

|

|||||

|

36% |

19% |

36% |

- |

- |

9% |

(C) |

|

54% |

36% |

9% |

- |

- |

- |

(M) |

I gain feelings of self-worth from the position I occupy in my ethnic community.

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

|

|

___________________________________________________________________________________ |

|

|||||

|

36% |

27% |

19% |

9% |

- |

9% |

(C) |

|

45% |

27% |

19% |

9% |

- |

- |

(M) |

I feel most satisfied when I am engaged in social activities with other Lithuanians.

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

|

|

___________________________________________________________________________________ |

|

|||||

|

36% |

45% |

9% |

- |

- |

9% |

(C) |

|

27% |

36% |

27% |

9% |

- |

- |

(M) |

I am interested in the future of the Lithuanian homeland.

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

|

|

__________________________________________________________________________________ |

|

|||||

|

63% |

9% |

19% |

- |

- |

9% |

(C) |

|

45% |

19% |

36% |

- |

- |

- |

(M) |

I feel most satisfied when I am engaged in activities within the Lithuanian community.

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

|

|

__________________________________________________________________________________ |

|

|||||

|

27% |

36% |

27% |

- |

- |

9% |

(C) |

|

27% |

36% |

19% |

1 9% |

- |

- |

(M) |

I feel it is important that Lithuanian-(Americans/Canadians) visit Lithuania at least once in their lifetime.

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

|

|

__________________________________________________________________________________ |

|

|||||

|

45% |

9% |

1 9% |

19% |

- |

9% |

(C) |

|

63% |

9% |

27% |

- |

- |

- |

(M) |

I feel most satisfied when I am in the circle of my Lithuanian friends.

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

|

|

__________________________________________________________________________________ |

|

|||||

|

36% |

19% |

36% |

9% |

- |

- |

(C) |

|

27% |

27% |

27% |

- |

19% |

- |

(M) |

I feel it is important that Lithuanian-(American/Canadian-an) children attend Saturday school.

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

|

|

________________________________________________________________________________ |

|

|||||

|

63% |

- |

19% |

- |

9% |

9% |

(C) |

|

63% |

19% |

19% |

- |

- |

- |

(M) |

I feel it is important that Lithuanian-(Americans/Canadians) respect their parents' wishes to speak Lithuanian in their parents' home.

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

|

|

________________________________________________________________________________ |

|

|||||

|

63% |

9% |

19% |

- |

- |

9% |

(C) |

|

36% |

45% |

9% |

- |

9% |

- |

(M) |

I would want my children to be raised in a Lithuanian environment (i.e. attend Lithuanian school, speak Lithuanian in the home, socialize with other Lithuanians, participate in Lithuanian organizations and clubs, etc.)

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

|

|

__________________________________________________________________________________ |

|

|||||

|

63% |

9% |

- |

9% |

9% |

9% |

(C) |

|

54% |

27% |

9% |

- |

9% |

- |

(M) |

It is important for Lithuanian-(Americans/Canadians) to stay together as a closely-knit group for the purpose of keeping the culture alive and growing outside the homeland.

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

|

|

__________________________________________________________________________________ |

|

|||||

|

54% |

19% |

27% |

- |

- |

- |

(C) |

|

54% |

36% |

- |

9% |

- |

- |

(M) |

Lithuanian-(Americans/Canadians) should speak Lithuanian amongst themselves.

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

|

|

__________________________________________________________________________________ |

|

|||||

|

9% |

45% |

19% |

9% |

9% |

9% |

(C) |

|

19% |

27% |

19% |

19% |

19% |

- |

(M) |

In order to keep the Lithuanian culture alive in North America Lithuanian-(Americans/Canadians) should participate as fully as possible in their own cultural community.

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

|

|

__________________________________________________________________________________ |

|

|||||

|

54% |

19% |

1 9% |

9% |

- |

- |

(C) |

|

27% |

54% |

- |

- |

19% |

- |

(M) |

It is important that other (Americans/Canadians) be made aware of the Lithuanians' fight for freedom for their homeland.

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

|

|

__________________________________________________________________________________ |

|

|||||

|

81% |

9% |

9% |

- |

- |

- |

(C) |

|

72% |

19% |

- |

9% |

- |

- |

(M) |

To be a Lithuanian-American/Canadian) means to carry responsibility to be politically active in the fight for Lithuania's freedom.

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

|

|

__________________________________________________________________________________ |

|

|||||

|

9% |

63% |

9% |

9% |

9% |

- |

(C) |

|

9% |

36% |

19% |

9% |

9% |

19% |

(M) |

I have a duty to educate others about the Lithuanian culture.

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

|

|

__________________________________________________________________________________ |

|

|||||

|

27% |

45% |

19% |

- |

9% |

- |

(C) |

|

19% |

19% |

63% |

- |

- |

- |

(M) |

Of those people whom you would call your friends what proportion are Lithuanian?

|

all of them |

nearly all of them |

more than half |

less than half |

none |

|

|

________________________________________________________________________________ |

|

||||

|

9% |

45% |

36% |

- |

9% |

(C) |

|

- |

45% |

9% |

45% |

- |

(M) |

I always celebrate Christmas Eve Supper (Lith. Kūčios) with my family.

|

Yes |

Sometimes |

No |

|

|

________________________________________________________ |

|

||

|

63% |

9% |

27% |

(C) |

|

100% |

- |

- |

(M) |

I always celebrate Lithuanian Independence Day (February 16th).

|

Yes |

Sometimes |

No |

|

|

_______________________________________________________________ |

|

||

|

36% |

27% |

36% |

(C) |

|

81% |

19% |

- |

(M) |

I celebrate February 16th by attending a Lithuanian function.

|

Yes |

Sometimes |

No |

|

|

_______________________________________________________________ |

|

||

|

54% |

19% |

27% |

(C) |

|

81% |

19% |

- |

(M) |

I always celebrate Easter with my family.

|

Yes |

Sometimes |

No |

|

|

_______________________________________________________________ |

|

||

|

45% |

27% |

27% |

(C) |

|

91% |

9% |

- |

(M) |

I attend Mass at a Lithuanian church only as an obligation I am fulfilling for my parents.

|

Yes |

Sometimes |

No |

|

|

_______________________________________________________________Ž |

|

||

|

19% |

19% |

63% |

(C) |

|

-% |

45% |

54% |

(M) |

Lithuanians should make themselves known by their Lithuanian names in all of their non-Lithuanian environments.

|

Yes |

Sometimes |

No |

|

|

________________________________________________________________ |

|

||

|

72% |

9% |

19% |

(C) |

|

81% |

9% |

9% |

(M) |

I believe the family is important in keeping our culture alive.

|

Yes |

No |

|

|

___________________________________________ |

|

|

|

91% |

9% |

(C) |

|

81% |

19% |

(M) |

I am very conscious of, or preoccupied with, my nationality.

|

Yes |

Sometimes |

No |

|

|

_________________________________________________ |

|

||

|

54 |

27 |

19% |

(C) |

|

45 |

54 |

- |

(M) |

[1] Lithuanian Saturday school is offered in several areas in North America, most notably, Chicago, Detroit, Toronto and Montreal. This is similar to a normal day at public, grades are K-12. Subjects include Lithuanian language, history, music, art and literature.

[2] Dėdė=uncle

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

VilNews e-magazine is published in Vilnius, Lithuania. Editor-in-Chief: Mr. Aage Myhre. Inquires to the editors: editor@VilNews.com.

Code of Ethics: See Section 2 – about VilNews. VilNews is not responsible for content on external links/web pages.

HOW TO ADVERTISE IN VILNEWS.

All content is copyrighted © 2011. UAB ‘VilNews’.

Click on the buttons to open and read each of VilNews' 18 sub-sections

Click on the buttons to open and read each of VilNews' 18 sub-sections

Jennifer has written an outstanding article. It must have taken an extraordinary amount of thought and work to create it.

Her distinction between geographical nationalism and organic nationalism reflects the experiences of many Lithuanians and their descendants.

We still tingle with emotion when we hear "The Star Spangled Banner," "O Canada," ""Nkosi sikelel' iAfrika," ""La Marseillaise"" or the national anthems of dozens of other countries scattered across the earth where we live. At the same time, our blood stirs when ""Lietuva, Tėvyne mūsų" proclaims the hopes of those who risked their lives to create a new nation on 16 February 1918.

Tegul Tavo vaikai eina

Vien takais dorybės,

Tegul dirba Tavo naudai

Ir žmonių gėrybei.

(Let your children always follow

Only roads of virtue,

May your own, mankind’s well-being

Be the goals they work for.)

I have been thinking about Jennifer's question all week. What defines Lithuania? What better way to define Lithuania than through our words and actions? Let us help, encourage, and inspire each other as our national anthem call on us to do. . Let us give help to those in need wherever they live, whether they are Lithuanian, American, Canadian, South African, French or just plain human.

As Thomas Paine, the author of "Common Sense" and one of the founding fathers of the United States wrote, "The World is my country, all mankind are my brethren, and to do good is my religion."

I have always enjoyed Jennifer's articles in Lithuanian Heritage Magazine, which were primarly anecdotal in nature. Imagine my surprise to see such a lengthy, eloquent discourse on what it means to be Lithuanian! This article made me realize why my attendance at Saturday Lithuanian School was so important –my parents' generation was one of the first to be instructed in their native language and did not want to let the language die out.

[…] Read more… […]