THE VOICE OF INTERNATIONAL LITHUANIA

|

VilNews has its own Google archive! Type a word in the above search box to find any article.

You can also follow us on Facebook. We have two different pages. Click to open and join.

|

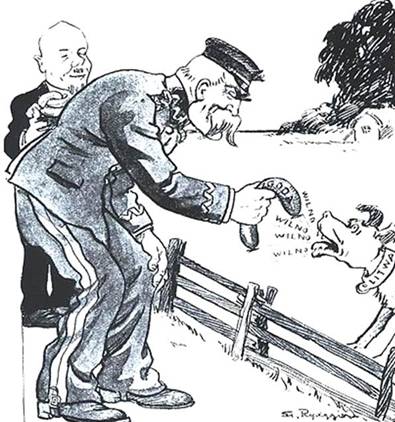

A satirical picture from interwar Polish press (around 1925-1935): a caricature of Marshal Józef Piłsudski and Lithuania, criticizing Lithuanian unwillingness to compromise over Vilnius region. Marshal Piłsudski offers the sausage labeled "agreement" to the dog (with the collar labeled Lithuania); the dog barking

"Wilno, wilno, wilno" replies: "Even if you were to give me Wilno, I would

bark for Grodno and Białystok, because this is who I am."

The tension will continue, until Poland will treat Lithuania

again as a sovereign and independent country

Opnion: Algimantas Gureckas

During the interwar period between First and Second World Wars the political leadership of reconstituted Poland aspired to a European great power status and conducted a policy of territorial expansion against its neighboring countries. As a result of several military campaigns in 1919-1920, Poland acquired considerable territories inhabited by non-Polish populations [see our VilNews articles on the Polish/Lithuanian war 1919-1920 at https://vilnews.com/?p=11551].

In Yalta and Potsdam conferences of 1945, the leaders of the victorious powers, United States of America, Great Britain, and the Soviet Union, established post-war borders of the Polish Republic. They endorsed the 1920 Curzon Line as its eastern frontier (1). This detached Western Ukraine, Western Belarus (2), and Vilnius region from Poland. In order to compensate Poland for the loss of these extensive, albeit mostly non-Polish territories, they assigned to it highly developed German territories of southern East Prussia, eastern Pomerania, Neumark, and Silesia (3). The victorious powers also autorized the expulsion of the entire German population from these territories(4).

The Polish people accepted the German lands as their due compensation for their suffering under the harsh German occupation during the war, but they regarded the loss of the eastern borderlands ("Kresy") as unjust detachment of territories lawfully belonging to the Polish state. However, Polish political leadership, the ruling communist regime, as well as the democratic underground, realized that any Polish claims to the lost territories in the East would undermine the Polish title to the newly acquired valuable lands in the West. Thus, eventually the view promoted by Jerzy Giedroyc, editor of an influential journal Kultura, and his collaborator Juliusz Mieroszewski prevailedthat Polish nation and state should sincerely renounce any claims to the interwar eastern territories (5).

This view remained the official policy of the Polish state after it regained its genuine independence in 1989, until 2010, when, after 65 years of Polish settlement, the Polish government and people at last felt entirely secure in those lands. This enabled Polish government to resume the interwar claim to a regional great power status (6) and to participate as such in a Moscow-Warsaw-Berlin-Paris axis. It is uncertain whether the Polish government also intends to pursue the interwar policy of territorial expansion in the east and to revive Polish claims to Ukrainian, Belarusian and Lithuanian lands. A statement by the Radosław Sikorski, Polish Minister of Foreign Affairs, denying that during the interwar period Vilnius has been occupied by Poland, can be interpreted as challenging Lithuania's right to its capital. It is unclear what the ultimate intensions of the Polish government are, but its intrusive nationalistic policies toward Lithuania and Belarus are causing considerable apprehension in those countries (7). A considerable portion of the Polish people in Poland support these aggressive policies.

The ostensible reason of the Polish dissatisfaction with Lithuania and Belarus is the treatment of the Polish minority in these countries.

Polish minority in Lithuania

Polish people constitute the largest national minority in Lithuania. The national or ethnic composition of population of Lithuania is shown in Table 1:

Table 1: National Composition of the Population of Lithuania According to the Census of 2001

Number of People Percent

Nationality in Thousands of the Total Population

Lithuanians 2 907.3 83.45

Poles 235.0 6.74

Russians 219.8 6.31

Belarusians 42.9 1.23

Ukrainians 22.5 0.65

Jews* 4.0 0.12

Germans 3.2 0.09

Tatars 3.2 0.09

Latvians 3.0 0.08

Roma 2.6 0.07

Armenians 1.5 0.04

Other nationalities 6.1 0.18

Unknown** ___32.9 0.94

Total 3 484.0

* In Lithuania, as well as in other Central and East European countries, Jews are considered as belonging both to the Jewish religion and to the Jewish nationality. A Jew who is an atheist or has converted to some other religion is counted as a person of Jewish nationality, but not of a Jewish religion. Census of 2001 found 4007 persons in Lithuania belonging yo Jewish nationality, but just 1275 of them confessing Jewish religion.

** People who did not identify themselves with any nationality or an ethnic group and those who refused to declare their nationality or ethnicity.

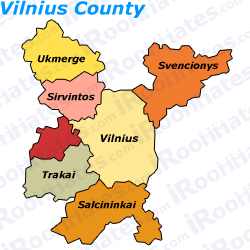

Polish minority is concentrated in the southeastern section of the country. Cities, country districts, and municipalities with significant Polish populations are shown in Table 2:

Table 2: Polish Population in Lithuania's Cities and Districts According to the Census of 2001

Total Inhabitants of Percent

Poles the City or District of Poles

City or District in Thousands in Thousands in the City or District

City of Vilnius 104.4 553.9 18.86

Vilnius District 54.3 88.6 61.32

Šalčininkai District 31.2 39.3 79.48

Trakai District 12.4 37.4 33.18

Švenčionys District 9.1 33.1 27.43

City of Visaginas 2.5 29.6 8.60

Elektrėnai Municipality 2.2 28.9 7.52

Varėna District 2.1 31.1 6.64

Molėtai District 2.1 25.4 8.09

Širvintos District 2.0 20.2 9.99

Ignalina District 1.9 23.0 8.29

City of Kaunas 1.6 378.9 0.42

Zarasai District 1.5 22.8 6.65

Druskininkai Municipality 1.0 25.4 3.91

Elswhere in Lithuania 6.6 2146.3 0.31

Total 235.0 3484.0 6.74

An ethnic Polish enclave

The data indicates that 44.5% of Lithuania's Poles live in the capital city Vilnius. A slightly larger portion, 45.6%, lives in the surrounding four districts of Vilnius, Šalčininkai, Trakai, and Švenčionys. The remaining 9.9% of Lithuania's Poles are scatered throughout the entire country. In Vilnius and Šalčininkai districts they constitute an absolute majority. Area where the Poles predominate encompasses these two districts and extends to the southeastern section of the Trakai district and to the southern part of the Švenčionys district. Thus, the Polish area almost surrounds Vilnius. To the west of Vilnius there is a mixed area where people speak Polish and Lithuanian. This area extends about 20 km from Vilnius. Area of Polish majority extends 20 km north from the Vilnius city limit, 50 km south, and 15 km east (8). This Polish majority area extends also beyond Lithuania into Belarusian territory, into the Voranava district where Poles constitute 83 percent of the population (9). Beyond the Polish area to the west and north live Lithuanians, and to the east and south -- Belarusians. The Polish area in Lithuania and Belarus is an ethnic enclave. It is separated from the main Polish area in Poland by an area inhabited by Lithuanians and Belarusians. Until 1920 there was no Polish immigration and settlement in the countryside around the city of Vilnius. The Polish enclave was created entirely by Polonization of the Lithuanian peasants during the 19th and the beginning of the 20th centuries (10). The configuration of the Polish area around Vilnius indicates that it has originated as a result of the cultural, linguistic, and economic influence of the city upon its surrounding countryside.

Spread of Polish language and cultural influence in Lithuania

Jadwiga with her husband, Jogaila; statue in Kraków, Poland

Jogaila, a pagan king of Lithuania, converted to Christianity, and, upon marriage to a Polish queen Jadwiga, became with her a co-ruler of Poland in 1386. He ordered all Lithuanians to accept Christianity and be baptized. Polish priests conducted Lithuania's christianization and remained in Lithuania as that country's clergy. They held the religious services in the Latin and Polish languages and exerted Polish cultural influence in the newly converted nation. Another source of Polish influence was the grand ducal court. Jogaila, becoming the king of Poland and retaining the title of the supreme ruler of Lithuania, established long lasting dynastic ties between Lithuania and Poland. Although the ruling dynasty was of Lithuanian origin, Jogaila's grandchildren, the future Kings of Poland and Grand Dukes of Lithuania, adopted the Polish language and culture. Lithuania's aristocracy and later also the lower nobility followed the example of their rulers and also became Polish speakers (11). In 1569 Lithuania and Poland joined in the Commonwealth of Two Nations. However, Lithuania's aristocracy and nobility remained conscious of their Lithuanian nationality; they were persistent defenders of Lithuania's political rights and interests and dedicated guardians of its heritage and traditions (12).

In the 14th century Vilnius, the capital of Lithuania, became a multinational city of Lithuanians, Germans from Livonia and Russians from Russian principalities under the suzerainty of the Lithuanian pagan kings (13). In the 16th and 17th centuries Jews and some Poles settled in Vilnius. By the middle of the 17th century Polish language and culture became predominant in the city (14). At the end of the 18th century, an opinion spread amongst the Polish elite in Poland that the relative weakness and vulnerability of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth derived from its dual structure and its multinational character. As a result an attempt was made to convert the Commonwealth into a unitary Polish state and quickly assimilate Lithuanians, Ukrainians, Belarusians, Latvians, Germans, and even Jews into a Polish nation (15). However, before this program could be implemented, powerful and expansionist neighbors, Russia, Prussia, and Austria, partitioned the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth out of existence in 1795.

A Polish program to assimilate other nationalities of the defunct Commonwealth, however, continued under the Russian and Austrian rule (16). In Lithuania the Polish speaking urban people in Vilnius and other cities began to identify themselves as Poles in late 18th century and the beginning of the 19th. Many members of the Polish speaking Lithuanian nobility identified themselves as gente lituani, natione poloni (of Lithuanian descent and Polish nationality) (17). Examples of such adherence to two nations were the general Thaddeus Kosciusko and poet Adam Mickiewicz. Only gentry in Samogitia, a western section of Lithuania, whether speaking Polish or a Lithuanian dialect, designated) themselves simply as Samogitians (žemaičiai) (18). At this time the country people around Vilnius, under influence of the Polish speaking Catholic clergy and pressure of Russian administration, began to switch from Lithuanian to the Belarusian language. The Polish priests promoted Belarusian over Lithuanian in order to further Polonization of their flock, since Slavic Belarusian was much closer to Polish than to Baltic Lithuanian. Meanwhile, Russian teachers and administrators considered Belarusian merely a dialect of Russian and were also promoting its use in Eastern Lithuania (19). During change of Lithuanian to Belarusian, the country people lost sense of their ethnic identity. They did not feel anymore belonging either to Lithuanian or Polish or Belarusian nationality and designated themselves as "locals" (tutejši) (20).

Until the middle of the 19th century, the main political objective of the Polish speaking Lithuanian nobility was the restoration of the multinational Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth (21). At that time, the ideas of the European nationalist democratic movement were not yet influential in Lithuania. However, later, during the Polish-Lithuanian insurrection of 1863-1864 against the Russian domination, some of its Lithuanian leaders were motivated by the idea of self-determination of the Lithuanian people. The most prominent of them was Rev. Antanas Mackevičius (1828-1863) (22).

Lithuanian national movement

After the unsuccessful insurrection in 1863, Lithuanian national movement proclaimed its cultural and political goal as equality of the Lithuanian nation with all other nations: "... we are the same human beings as our neighbors, and we want to enjoy the same rights, which belong to the entire humankind, just as our neighbors are enjoying them." (23)

Lithuanians were conscious that they were rather a small nation, thus their nationalism remained defensive and moderate. They never claimed any superiority against any other nation, and merely demanded equality and freedom to preserve and develop their language and culture in their country. This attitude had remained the enduring characteristic of Lithuanian nationalism to this day.

The spread in the 19th century of European nationalism based on national language, history, and cultural heritage, demanded that an individual person identified himself or herself with a definite nation. The formulation gente lituanus, natione polonus became untenable. In Lithuania the time of decision arrived with the census of the population of the Russian Empire in 1897. Although the census asked only about the native language, many members of nobility and other educated people apparently declared their nationality instead. Among Lithuania's nobility 24% declared themselves as Lithuanians (including Samogitians), 57% -- as Poles, 11% -- Belarusians, and 8% -- other nationalities (Germans, Tatars, Russians). There were considerable regional differences. In Samogitia 68% of the local gentry declared themselves Samogitians or Lithuanians, 29% -- Poles, and 3.0% -- other nationalities, while in the rest of Lithuania just 8% of the gentry identified themselves as Lithuanians, 67% as Poles, 14% as Belarusians, and 10% as other nationalities. In the district of Vilnius, without the City of Vilnius, there were 20% Lithuanian gentry, 52% Polish, 24% Belarusian, and 4% other nationalities (24).

In the city of Vilnius by native language there were 44% Yiddish or Hebrew speaking Jews, 34% Polish speakers, 15% Russian (mostly non-native administrative personnel), 4% Belarusian, 2% Lithuanian, and 2% other (German, Ukrainian, Karaite).

In the district of Vilnius, which at that time encompassed present districts of Vilnius and Širvintai and parts of districts of Šalčininkai, Molėtai and Astraviec, the 1897 census found 42% inhabitants whose language was Belarusian, 35% Lithuanian, 12% Polish and 11% speaking other languages (Yiddish, Russian, German) (25).

For the Poles the rise of Lithuanian national movement was an unpleasant surprise. They were convinced that Polish assimilation of Lithuanian people was already complete and did not expect their assertion of a separate national identity. National political and cultural leaders of Polish people in Poland and in Lithuania did not attempt to co-opt the emerging Lithuanian national movement; they met the unexpected development with anger and unalloyed hostility. Poles could not believe that Lithuanian people wished to break almost 500 year old political and cultural ties with the Polish nation and go their own way; Poles suspected that Lithuanian movement was instigated either by the Russian or German clandestine efforts to undermine Polish influence in Lithuania. That was an obviously erroneous supposition since in the second half of the 19th century both Russian, as well as German, governments were determined to Russianize or Germanize the Lithuanian people under their rule; consequently they were hostile to the Lithuanian national movement and were striving to suppress it (26).

In Lithuania the split between people who asserted their Lithuanian identity and those who considered themselves Polish was sharp and painful, in particular among Lithuania's nobility. Sometimes families were split according to family members' diverging decisions about their commitments to different nationalities. Thus one of two brothers, Gabriel Narutowicz, was elected the first president of the restored Polish Republic in 1922, while his brother, Stanislovas Narutavičius, was a signatory of Lithuania's Declaration of Independence in 1918 (27).

Sometimes families were split according to family members' diverging decisions about their commitments

to different nationalities. Thus one of two brothers, Gabriel Narutowicz (left), was elected the first

president of the restored Polish Republic in 1922, while his brother, Stanislovas Narutavičius (right),

was a signatory of Lithuania's Declaration of Independence in 1918.

Decisions about national identity -- Lithuanian or Polish -- were essentially subjective, depending on which historical tradition was cherished, such as the heroic defense of medieval pagan Lithuania against the might of the crusading Teutonic knights, or the struggles of the profoundly Catholic Poland against Moslem Turks, Orthodox Moscovites, as well as against Protestant Swedes and Prussian Germans. There were differences also on a program for a desirable future: Lithuanian ideal of a fair, egalitarian society based on radical agrarian reform, or a preservation of a socially privileged way of life of the Polish gentry. Economic and financial considerations also affected self-identification of individuals. A specter of a radical agrarian reform contributed to hostility of the gentry toward the Lithuanian national movement, while landless agricultural workers supported the prospect of redistribution of land.

However, only a few intellectuals were inclined to respect subjective individual decisions. The great majority of Lithuanians and Poles were convinced that all decisions about belonging to one or the other nationality could and should be based on objective historical, social, and political considerations. Different choices were unacceptable, indeed they were treasonable. Thus any Lithuanian Pole was considered a traitor of his country -- Lithuania, while, according to the view from the other side, any Lithuanian who asserted his nationality was condemned as a traitor to the Polish fatherland, that, of course, included the entire Lithuania and its history. Obviously such attitudes on both sides allowed no room for any compromises.

However, it would be a mistake to blame both sides in the dispute as equally intolerant and unreasonable. Lithuanians in their conflict with Poles were defending the survival of what remained of their nation, while the Poles attempted to enlarge their nation and to expand their national territory. The Poles as a larger, stronger, and more influential party, did not see any need for compromises and were determined not to let Lithuania go its own way. The hostile relations between Lithuanians and Poles and later between independent Poland and Lithuania were the result of decisions and actions of the stronger party to impose its will on the smaller neighbor.

Peaceful and good neighborly relations can be established only when the larger and stronger power takes into account and accommodates vital interests of the smaller and weaker neighbor nation (28).

Recovered freedom and the conflict between the liberated nations

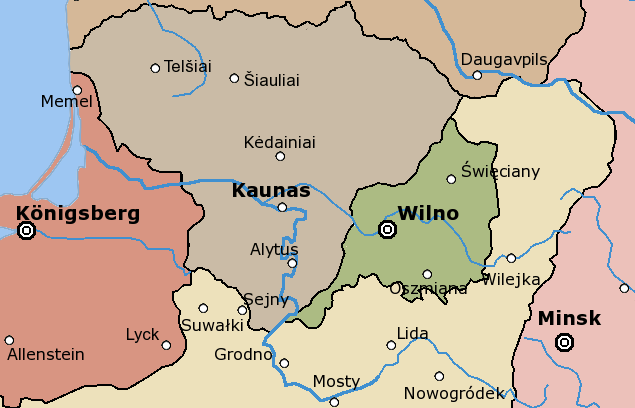

South-eastern Lithuania, Vilnius included, was occupied by Poland during the interwar period.

Picture: Celebration of the incorporation of Vilnius Region to Poland in 1922.

When the First World War ended in 1918, both Lithuania and Poland proclaimed their restoration as free and independent countries. These proclamations, however, contained seeds of conflict between them. The reconstituted Poland claimed to be the only heir to the defunct Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. It ignored the dual structure of the Commonwealth and established reborn Poland as a unitary state. Although the Commonwealth was a multinational country, the restored Poland was to be a Polish nation state. This state claimed all the lands of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth before its first partition in 1772, which included all of Lithuania (29).

Meanwhile the restored Lithuania claimed the legacy of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, that was a member state of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth (30). Although the Grand Duchy also was a multinational country, with mainly Lithuanian and Belarusian population, the restored Lithuania was to be a Lithuanian nation state. The inherent contradiction, that a reconstituted multinational country should be a nation state, was resolved when the Constituent Assembly (Steigiamasis Seimas) in 1920 proclaimed that restored Lithuania should have ethnographic boundaries (31). Thus it limited Lithuania's territorial claims just to Lithuanian lands, and the Belarusian ethnic territory was separated from the re-established Lithuania.

Poland did not recognize the restored Lithuanian state. It denied that restored Lithuania had anything in common with the Grand Duchy of Lithuania and claimed Lithuania as an integral part of Poland (32). However, Lithuanian resistance was too strong for Poland to seize Lithuania by the force of arms, since in 1918-1920, Poland was fighting simultaneously six wars with all of its neighbors (33). An attempt of a Polish underground organization to overthrow Lithuania's government on August 29, 1919, fizzled in the face of lack of any support by the population (34). After that failure, Poland attempted at least to seize as large portion of Lithuania's territory as possible, including its historical capital city of Vilnius.

During the Polish-Soviet war of 1919 to 1920, Polish invasion of Lithuania led to a full scale, albeit undeclared war. On October 7, 1920, a Polish-Lithuanian armistice agreement was signed at Suwałki. It established a line of demarcation that left Vilnius to Lithuania (35). The armistice agreement specified that "[t]he present agreement . . . remains in force until all litigious questions between the Poles and the Lithuanians shall be definitely settled." (36) Two days later, however, on October 9, 1920, Polish forces suddenly attacked the Lithuanians and seized Vilnius. At that time, the Polish government claimed that Vilnius was taken by mutinous troops, however, later the Chief of State and Commander-in-Chief of the Polish Armed Forces Marshal Józef Piłsudski publicly acknowledged that General Lucjan Żeligowski, who allegedly staged the mutiny, acted under Piłsudski's direct orders (37).

Map of the (Polish) Republic of Central Lithuania 1922-1939 (in green).

The Lithuanian people were shocked by the sudden loss of their historical capital city. They perceived it as an unjust and treacherous act. The Polish battle cry: "For our freedom and yours!" was exposed as dishonest and self-serving. In contrast, Poles generally rejoiced in the shrewd and successful military and political exploit by their leaders. Lithuanian people and their government were convinced of their right to their capital. At that time Finland also became independent nation, and nobody questioned that Helsinki, its capital, belonged to Finland, eventhough a clear majority of the people living in the city and in the province around it were Swedish speakers. Similarly German people predominated in Czechslovakia's capital Prague, and Latvia's and Estonia's German and Russian speakers constituted majorities in capitals Riga and Tallinn. Accordingly, Lithuania expected that its historic right to its Polish and Yiddish speaking capital Vilnius, and the Belarusian speaking Vilnius district, would also be recognized and honored. Lithuania's government expected that the newly created League of Nations would solve the Vilnius conflict in Lithuania' favor (38).

The League of Nations was dominated by France and Great Britain, the main victors of World War I. They were interested in establishing a large and strong Poland as a counterweight to Germany and the Bolshevist Soviet Russia. For this reason the French government supported Poland without worrying much whether it was right or wrong. The British were somewhat skeptical. They did not believe that Poland containing large and hostile non-Polish populations could be a stable and strong country. However, wishing to avoid confrontation with France, the British did not object to the Polish territorial expansion , and thus the Poles prevailed in the international arena. The League of Nations was revealed as incapable to solve conflicts between nations against the wishes of the great powers (39).

On January 8, 1922, Polish administration conducted election to Vilnius Diet in the section of Lithuania occupied by the General Żeligowski's Polish troops. The League of Nations Military Control Commission observed the elections. In its report to the League of Nations it concluded that:

As the Lithuanians and Jews and a large proportion of the White Russians [Belarusians]

officially abstained from taking part in the elections, and that, moreover, the elections

were carried out under military occupation, where the Polish element had all the

government machinery at its disposal, it would seem impossible to regard the present

Diet of Vilna [Vilnius] as the real and sincere expression of the whole population of

the electoral territory. (40)

Nevertheless, Poland annexed Vilnius and its territory on March 24, 1922. The Conference of Ambassadors, consisting of the French, British, Italian, and Japanese representatives, on March 15, 1923, formally assigned Vilnius and its territory to Poland. Lithuania rejected the decision of the Conference of Ambassadors and always vehemently denied the legitimacy of the Polish occupation and annexation of Vilnius (41).

POPE PIUS XI

In April, 1918 Pope Bededict XV appointed Archbishop Achilles Ratti (later Pope Pius XI) as apostolic visitator to Poland and “ex Russian countries”, including Lithuania. In 1921 apostolic visitator and delegate Rev. Antonio Zechini arrived in Kaunas. He publicly expressed the opinion that independent Lithuania could not exist by itself. Lithuania broke off diplomatic relations with the Holy See after the Concordat of 1925 established an ecclesiastical province in Wilno thereby acknowledging Poland's claims to the city.

Lithuania consistently maintained this position until it recovered Vilnius and a portion of the Vilnius Territory in 1939. During the period of the Polish occupation, the 1928 and 1938 Constitutions of Lithuania designated Vilnius as the capital of the country (42).

The only great power that supported Lithuania's position on Vilnius was Soviet Russia, since 1922 -- the Soviet Union. It consistently recognized and upheld Lithuania's right to Vilnius and the surrounding territory. Consequently in 1939, when the Soviets invaded Poland and seized Vilnius, the Soviet Union returned it to Lithuania (43).

Lithuania's government realized that the Soviet Union supported Lithuania's right to Vilnius in order to obstruct formation of a defensive alliance between the Baltic states and Poland . However, at that time Lithuania had lost its illusions about the commitment of the League of Nations and of the western great powers to uphold justice and international law. Lithuania accepted Soviet support since it learned that the conduct of countries in international relations was determined only by the requirements of the realpolitik.

For 16 years, from 1923 until 1939, the Vilnius issue remained a frozen conflict, a stalemate. The western powers did their best to ignore it, but the problem did not go away. The Polish administration in Vilnius hurried to forcibly assimilate Lithuanians, Belarusians, and even Jews in the occupied territory. It openly discriminated against them, closed their schools and organizations, persecuted their cultural and political leaders (44). During the 1926-1939 period Poland was under a military dictatorship. Polish administration took various measures to prevent Lithuanians to from establishing residence in the city of Vilnius and, in some cases, evicted them in order to keep the number of Lithuanians in Vilnius as low as possible (45). However, Lithuanians in the occupied territory did not succumb to the pressure of forcible Polonization. The percentage of Lithuanians in the area that was Vilnius district in 1897 remained at the same 35 % level in 2001 as it was 104 years ago, during the 1897 census.

In contrast, the Polish policy of Polonization was successful among the Belarusian speaking population. During the Polish occupation, the Belarusian speaking people living in the countryside, who did not identify themselves with any nationality or any ethnic group, accepted Polish identity. The Belarusian dialect intermixed with some Polish words they designated as their Polish language. In the Vilnius district the census of 1897 found 12 % Poles and 44 % Belarusians. In the same area in 2001 the percentages were reversed: 47 % Poles and 10 % Belarusians. Obviously most of the Belarusian speakers now identified themselves as Polish. This shift created the present Polish enclave around Vilnius.

Deportations, resettlements of populations, massacres and the Holocaust

On June 15, 1940, Soviet Union invaded and occupied Lithuania, and on August 3 it annexed the occupied country. After a year of occupation, on June 14, 1941, teams of armed activists and troops under the Soviet People's Commissariat of Internal Affairs (NKVD) started mass deportation of Lithuanian, Polish, and Jewish people to Siberia and Central Asia. The deportees were crammed into crowded railroad cattle cars, women, old people, and children. Most babies and numerous old people died during the lengthy transit in inhuman conditions. The entire country was terrified by this unheard-of brutal action. Similar large scale deportations were salso conducted at the same time in Latvia and Estonia. The deportations were interrupted by the German attack against the Soviet Union, but 17 500 persons were deported from Lithuania (46).

The Lithuanians greeted the German soldiers as liberators from the terror and horrors of the Soviet occupation. However, it soon became obvious that Nazi Germany was just another brutal and murderous occupier. From the first days of the German-Soviet war special German commandoes started killing Jews in the conquered cities and villages under their control. During three years of the German occupation (1941-1944), their special commandoes and their local henchmen killed about 195 000 Lithuanian Jews, 94% of the total Jews in the country before the German-Soviet war. That number includes 72 000 Jews from Vilnius and elsewhere murdered at Paneriai forest near Vilnius. In addition about 8 000 non-Jewish Poles and Lithuanians were executed in the same forest (47).

Only a few thousand Jews survived the German occupation. The 1959 census found 16 300 Jews in the city of Vilnius, but some of them were Soviet Jews who settled in Vilnius after the war. In 1989, during the last days of the Soviet occupation, 9 100 Jews lived in Vilnius. When Lithuania regained its independence, emigration became free, and many Jews, because of difficult economic conditions, emigrated to Israel, United States of America, or other Western countries. The census of 2001 found only 2 800 Jews in Vilnius.

On July 13, 1944, the Soviet Red Army recaptured Vilnius. By February 4, 1945, it drove the Germans from the entire territory of Lithuania. About 60 000 Lithuanians fled west from the advancing Soviets. Several thousand of the refugees were from Vilnius and the surrounding area.

The Soviets reestablished their administration and resumed massive arrests and periodic deportations. It is estimated that about 300 000 Lithuanian people, 10% of the total population, were killed or deported during the 9 year period from 1944 until 1953 (48). Upon Stalin's death in 1953 the deportations ceased.

The Polish people were provided an opportunity to escape from Stalin's terror in the Soviet occupied Lithuania to a relative safety of Poland. After the war, the Soviet Union and Poland signed an agreement permitting ethnic Poles to relocate from Lithuania, Belarus, and Ukraine to Poland, and 243 600 Lithuania's Poles, about one half of the total Lithuania's Polish population, resettled to the previously German territories which the Potsdam conference assigned to Poland and authorized the Polish government to expel the entire German population (49). Almost all the Polish settlers in Vilnius and the surrounding area from the 1920-1939 Polish occupation, Polish refugees who escaped to Lithuania from the Soviets and Germans in 1939, any remaining Polish gentry, most of the Polish middle class, and many farmers left Lithuania for Poland (50). Many farms were left empty. Stalin did not allow Lithuanians from other sections of the country to take over the abandoned farms. He obviously had other plans for that section of Lithuania (51).

The abandoned farms did not stay empty for very long. The people from the nearby districts of Belarus moved to Lithuania and took possession of them. The newcomers were Belarusian speaking Poles of Lithuanian descent -- just like the majority of the local population. Therefore they integrated themselves easily with the locals (52).

World War II affected the city of Vilnius much more than its countryside. When the Soviet army captured Vilnius there were just about 99 000 people in the city, about a half of its regular population. About 82% of them were Poles, 7% Russians, 7% Lithuanians, 1% Belarusians and 1% Jews, survivors of the Holocaust (53). In the wake of the Soviet army followed the Soviet administration including its security services. Soon after numerous Russian settlers came to Vilnius looking for relatively better living conditions than in their Soviet homeland. After more than half of the city of Vilnius Polish population resettled to Poland, Russian newcomers became a majority of the city population. However, when the Soviets started forcible collectivization of the agriculture in Lithuania, many of its farm based people escaped the serfdom of the Soviet collective farms and migrated to the cities. The population of Vilnius and all other Lithuania's cities increased rather quickly. By 1959 Lithuanians in Vilnius became a majority and absolute majority before 1989.

When Lithuania regained its independence in 1990, many Russian administrators lost their jobs and returned to Russia. This was the last large scale movement of the population in Lithuania that started with the Soviet occupation in 1940. The change of the national and ethnic make-up of the Vilnius city during a century from 1897 to 2001 is shown in Table 3:

Table 3: The National and Ethnic Composition of Population in the City of Vilnius

Population in Thousands

Nov. 30,

1897 1931 1944 1959 1989 2001

Lithuanians 3.2 1.6 * 8.0 79.4 291.5 318.5

Poles 47.8 128.6 85.0 47.2 108.2 104.4

Russians 31.0 7.4 8.9 69.4 116.6 77.7

Belarusians 6.5 1.7 2.1 14.7 30.3 22.5

Ukrainians 0.5 0.2 0.5 6.6 11.5 7.2

Jews 61.8 54.6 1.7 16.3 9.1 2.8

Other nationalities_ 3.7 1.0 0.4 2.5 9.5 20.8

Total 154.5 195.1 106.6 236.1 576.7 553.9

Percentages

Nov. 30,

1897 1931 1944 1959 1989 2001

Lithuanians 2.1 0.8 * 7.5 33.6 50.5 57.8

Poles 30.9 65.9 79.7 20.0 18.8 18.7

Russians 20.1 3.8 8.4 29.5 20.2 14.0

Belarusians 4.2 0.9 2.0 6.5 5.3 4.0

Ukrainians 0.3 0.1 0.4 2.8 2.0 1.3

Jews 40.0 28.0 1.6 7.0 1.6 0.5

Other nationalities 2.4 0.5 0.4 0.6 1.6 3.7

Total 100.0 100.0 100.0 100.0 100.0 100.0

* During the 19 year (1920-1939) period of Polish occupation, Polish administration in Vilnius took various measures to prevent Lithuanians from establishing residence in Vilnius and, in some cases, evicted them in order to keep the number of Lithuanians in Vilnius as low as possible.

Aggressive Leadership of Peaceful People

The sandy soils around Vilnius are meager for farming. Thus most people living from agriculture in that area, although hard working, are still rather poor. This may be the reason why they are more dependent on their local political and municipal leadership than the people from other sections of the country.

The sandy soils around Vilnius are meager for farming. Thus most people living from agriculture in that area, although hard working, are still rather poor. This may be the reason why they are more dependent on their local political and municipal leadership than the people from other sections of the country. However, their trust in their leaders appears to be rather limited. When Lithuania has regained Vilnius in 1939, the Polish leadership called Polish people to resist Lithuania's sovereignty and authority. However, the people realizing that the only realistic alternative to Lithuania at that time was either Soviet or German occupations, remained calm and friendly to the Lithuanian administration.

The Soviet army invaded and occupied Lithuania in 1940, and the Germans followed in 1941. The Soviets upon returning in 1944, held the country under their occupation until 1990. During the 50 year period of Soviet-German-Soviet occupations, the position of the leadership of the Polish population was invariably opposite to any prevailing Lithuanian standpoint. Several attempts by Lithuanian and Polish representatives to coordinate their resistance against German occupation failed in disagreement on whether Vilnius and its territory rightfully belonged to Lithuania or Poland (54). Finally it came to armed clashes between Polish guerrilla units and the Lithuanian Vietinė Rinktinė (Local Defense Force) (55).

During the 1944-1953 nine-year Lithuanian guerrilla war against the Soviet occupation, the remnants of the Polish Armia Krajowa in the Vilnius region also fought the Soviets for a couple years, but there were no contacts and no coordination between these two anti-Soviet forces.

During the first four years of the second Soviet occupation, a radical change transpired in the leadership of the Polish population in Vilnius and the Vilnius region. The former leaders were extremely nationalistic, fiercely hostile to Russians, Germans, and Lithuanians. The Soviets arrested most of them. They were either executed or deported to Siberian labor camps. Those who were not detected by the Soviet security police, resettled in Poland. Eventually, new leaders emerged. They deferred to the Russians, hated Lithuanians, and upheld the Soviet system. Under their leadership, the Polish people in Lithuania became passive and submissive to the Soviet rule. The use of the Russian language slowly penetrated among Belarusian speaking Poles. Progressively more children were sent to Russian schools and fewer of them to Polish (56).

After long years of the second Soviet occupation, public demand for restoration of Lithuania's independence was raised in Vilnius for the first time in August 23, 1987 (57) . Poles were invited to participate. The location of the meeting was selected at the Adam Mickiewicz monument since the Polish poet was cherished by three nationalities -- Poles, Lithuanians, and Belarusians. But no Poles showed up.

In 1988 the Sąjūdis movement was organized in Vilnius. It pressed for dismantling of coercive Soviet policies in Lithuania, and eventually it escalated its demands to the restoration of Lithuania's independence (58). The Lithuanian people enthusiastically supported Sąjūdis in massive actions, meetings, and demonstrations. Majority of Lithuania's national and ethnic minorities, Jews, Germans, Tatars, Karaites, also supported Lithuania's quest for independence. The only opposition was by some Poles and the Russian newcomers (59) . However, their counterdemonstrations were embarrasingly small, and the organizers had to bus Russian and Belarusian reinforcements from Minsk, the capital of Belarus.

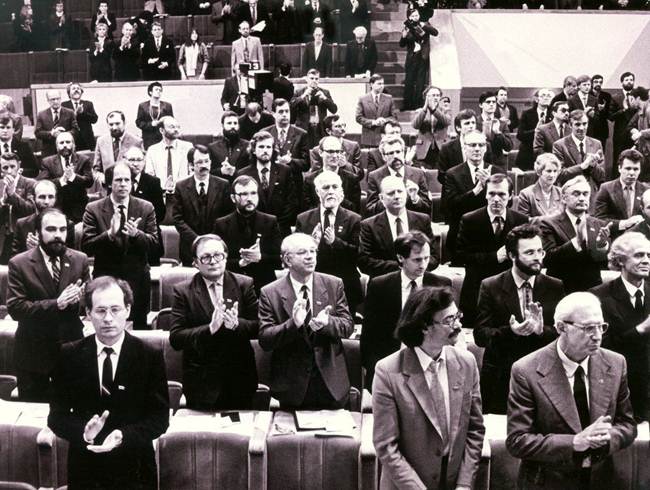

During elections to the Lithuania's Supreme Council in 1990, nine Polish deputies were elected. On March 11, 1990, a Declaration on Restoration of Lithuania's Independence was submitted for a vote to the Supreme Council. An overwhelming majority of 124 deputies voted for the declaration including three Polish deputies. While there were no negative votes, six of the remaining Polish deputies abstained (60). This crucial vote disclosed a split among the Polish representatives. A minority of them endorsed restoration of Lithuania's independence, while the majority opposed the foremost goal of the Lithuanian people. The majority was aggressive, being supported by Moscow and later by Warsaw. It accused the loyal Polish minority of treason to the Polish cause and was largely successful in marginalizing the moderate segment of the Polish ethnical community consisting mostly of intelectuals.

During elections to the Lithuania's Supreme Council in 1990, nine Polish deputies were elected. On March 11, 1990, a Declaration on Restoration of Lithuania's Independence was submitted for a vote to the Supreme Council. An overwhelming majority of 124 deputies voted for the declaration including three Polish deputies. While there were no negative votes, six of the remaining Polish deputies abstained. This crucial vote disclosed a split among the Polish representatives. A minority of them endorsed restoration of Lithuania's independence, while the majority opposed the foremost goal of the Lithuanian people. The majority was aggressive, being supported by Moscow and later by Warsaw. It accused the loyal Polish minority of treason to the Polish cause and was largely successful in marginalizing the moderate segment of the Polish ethnical community consisting mostly of intellectuals.

Prior to the February 9, 1991, plebiscite on independence of Lithuania, Polish political leadership called for a boycot of the vote. It seemed that there was some response in the Šalčininkai district where 25.0 % of the people, eligible to participate in the plebiscite, voted, 52.8 % of them voted for Lithuania's independence. However, in the Vilnius district (excluding the city) 42.8 % eligible voters participated in the voting; 56.6 % of them voting in favor of independence. Apparently a large segment of the inhabitants of the Vilnius district did not share the opposition of the Polish leadership to Lithuania's independence. Even more so, in the city of Vilnius, of 73.4 % who voted, 80.6 % cast their votes for independence (61).

After declaration of restoration of Lithuania's independence on March 11, 1990, the Polish leadership attempted to create a national territorial autonomy for the southeastern section of Lithuania inhabited mostly by the Polish and Belarusian speaking people. At the outset the initiators of the project declared that the autonomous region would be a part of the "Lithuanian S. S. R." (non-existant since the March 11, 1990, declaration of Lithuania's independence) (62). Subsequently on October 6, 1990, the Polish dominated Second Conference of the Deputies of the Local Soviets of the Vilnius Territory in Eišiškės officially declared that it did not recognize the validity of the October 10, 1939, treaty between the Soviet Union and Lithuania, that returned Vilnius and the Vilnius territory to Lithuania, and demanded its annulment (63). This was an undisguised assault against the territorial integrity of the restored Republic of Lithuania. This project to dismember Lithuania was closely coordinated with and supported by the leadership of the Soviet Communist Party and the Soviet secret services. The Soviet-Polish project was similar to the Soviet action to dismember Georgia and to sever South Ossetia from that country. After the collapse of the Soviet hardliner putsch in Moscow on August 21, 1991, Soviet TASS news agency reported that the "Vilnius region liberation army" had issued an ultimatum demanding a referendum in the southeastern section of Lithuania and threatened to take military action against Lithuanian armed forces (64). Lithuania's government ignored the ultimatum, and nobody ever heard anything about the "Vilnius region liberation army" again. Obviously the Soviet secret services did not find any Polish people in Lithuania willing to take up arms against their own country. Despite animosities and tensions between nationalities and ethnic groups in Vilnius and its surrounding area, there were no violent incidents between Lithuanians and Poles either in Vilnius or anywhere else in Lithuania since the end of the World War II.

The Polish secessionist action in Lithuania was acclaimed by some nationalistically inclined people in Poland, but the Polish government recognized that it was primarily a Soviet instigated project. After Germany's reunification in 1990, the main objective of the Polish government was securing recognition by the German government, German people, and the international community that the previous German territories were rightfully Polish. Warsaw persistently upheld the principle of unchangeability of existing borders between European countries. Since the German territories of Southern East Prussia, Eastern Pomerania, Neumark, and Silesia, were explicitly assigned to the Polish administration as a recompense for the loss of Western Ukraine, Western Belarus, and Vilnius, any Polish secessionist project in the neighboring countries would have been in a direct conflict with the Warsaw's policy on securing and protecting existing boundaries for the Polish Republic. Therefore, its government disapproved subversive schemes of the pro-Soviet Polish leadership in Lithuania. Poland signed a treaty that confirmed the existing boundary with Lithuania and entered into a treaty of good neighbourly relations recognizing Vilnius as the capital of Lithuania (65). This was the basis for a sixteen year period (1994-2010) of friendly relations and a strategical partnership between Poland and Lithuania.

Persistent Polish complaints and accusations against Lithuania's government and Lithuanian people of fictitious discrimination and persecution of the Polish people, of their language and culture did not elicit any significant resonance either in the United Nations or the international community since the Government of the Republic of Poland did not support them.

Undeclared Autonomy

In order to avoid conflicts with Polish ethnic minority, its politicians and activists, Lithuania's government adopted a policy of non-interference into the policies and conduct of the municipal governments of Vilnius and Šalčininkai districts. Soon non-interference turned into neglect, and the two districts actually evolved into Polish territorial semi-autonomous districts. A Polish political party called Electoral Action of Poles in Lithuania (EAPL) controlled all elections in the two Polish majority districts.

In order to avoid conflicts with Polish ethnic minority, its politicians and activists, Lithuania's government adopted a policy of non-interference into the policies and conduct of the municipal governments of Vilnius and Šalčininkai districts. Soon non-interference turned into neglect, and the two districts actually evolved into Polish territorial semi-autonomous districts. A Polish political party called Electoral Action of Poles in Lithuania (EAPL) controlled all elections in the two Polish majority districts. Elections invariably returned the same politicians to their offices in the municipal administration. This resulted in arrogant and corrupt administrations. In this regard the Polish districts were not an exception since there was also a high level of corruption in other parts of Lithuania. After regaining independence, in the elections of 1992 and 1993, the Soviet-era leadership was returned to power in Lithuania. This enabled an excessively large, sluggish, and corrupt Soviet-era bureaucracy to outlast the Soviet system and to entrench itself at all levels of administrtation.

Although the EAPL invariably won all municipal elections, its leadership was still insecure. The fact that its electorate consisted of Polonized Lithuanians and in the Šalčininkai district and the southern part of the Vilnius district the Poles were speaking Belarusian and not Polish, were apparently reasons for concern to the local Polish leadership that the Polish identity might be superficial and that the Lithuania's Poles might eventually assimilate with the Lithuanian ethnic nation. To counteract such a contingency the Polish leadership adopted a policy of hostility and confrontation with the Republic of Lithuania and the Lithuanian nation. At the present time this policy developed into an unending series of conflicts about subjects large and small.

According to the rules of Lithuanian orthography, non-Lithuanian personal names are written so as to enable a reader to pronounce them correctly, but the EAPL demands that the Polish names be recorded in the official documents as they are written in Polish and not as they are pronounced in Lithuanian (66). EAPL converted this basically lingvistic problem into a political issue. Another EAPL demand is to use bilingual and, in some locations, trilingual signs (Lithuanian, Polish, and Russian) for streets, towns and villages where Polish or Belarusian speaking people constitute a majority of the population (67).

Thus the EAPL leadership keeps raising one problem after another without seriously trying to find their resolution..

However, there is a genuine problem of legalized appropriation and theft of real property in Vilnius and its vicinity affecting some Polish original owners. Under the Soviet occupation the entire land of the country has been nationalized. There has not been any private ownership of land left either in the cities or in the countyside. Independent Lithuania has adopted a principle of restitution of land and existing buildings to the original owners or their heirs. However, that principle has been compromised by a provision in the restitution law, that allows a restitution claimant, instead of recovering previously owned or inherited parcel of land, to acquire land somewhere else in Lithuania. Thus smart and influential people have appropriated the most valuable land in the capital city Vilnius and vicinity that was not their own. It is much too complicated to understand the bureaucratic procedures how it has been accomplished. Just the result is clear. The original owners or their heirs have lost their property, influential outsiders have acquired valuable land and everything is legal. President of Lithuania Dalia Grybauskaitė is working to change the laws that allow such large scale corruption, but so far enforcement agencies and courts avoid confronting the rich and influential people, the so called oligarchs, and thus the revised laws are ignored. Moreover, in many cases the stolen property cannot be recovered since the statute of limitations has run its course.

This is not a problem of nationalities. Rich and influential people do not care about the nationalities and ethnic backgrounds of the original owners whose property they have appropriated. Lithuanian owners have been deprived of their property at the seashore and at other scenic locations where there have been no previous Polish owners. The EAPL persists in protesting in Seimas, the Lithuanian parliament, in Poland, and in the European Union the theft of property from their Polish speaking owners (68). The Lithuanian government and people should be grateful to the Polish activists for raising this issue to international level since their protests abroad might at last shore up the weak Lithuanian state to resist such schemes of its influential oligarchs.

Some Polish people in Lithuania disagree with the policies of the current leadership of the EAPL. About 13 percent of Polish children in the Vilnius district are being sent to Lithuanian schools in defiance of the pressure on their parents by the EAPL (69). Some Polish students at the Lithuanian universities view the complains and demands of the Polish leadership as groundless (70). Also a prominent member of Polish leadership in Lithuania, Mr.Ryšardas Maceikanecas, disagreed with its hostile and confrontational policies toward Lithuanians and Lithuania's government and became an outspoken Polish disident (71). However, Warsaw, as well as local Polish leadership, ignore these Polish disidents and their views.

A prominent member of Polish leadership in Lithuania, Mr.Ryšardas Maceikanecas, disagreed with its hostile and confrontational policies toward Lithuanians and Lithuania's government and became an outspoken Polish disident. However, Warsaw, as well as local Polish leadership, ignore these Polish disidents and their views.

Research in causes of unemployment or underemployment have discovered that young Poles looking for jobs are handicaped by their inadequate Lithuanian language skills (72). Vilnius and Šalčininkai districts have two different school systems. One system is administred by municipal governments. They are responsible for Polish schools with instruction of all subjects in Polish,, except for a single class in which the Lithuanian language is taught. The district governments maintain only a few, low quality, token schools in which instruction is in Lithuanian. Local Lithuanians in the Vilnius and the Šalčininkai districts are a minority at 22.4 percent and 10.4 percent respectively, and they complain about Polish discrimination against them (73). Therefore, in those districts the Ministry of Education has established a number of Lithuanian schools. These schools are attended not only by the children of local Lithuanians, but also by the children of those Polish parents, who want their children to learn and to be fluent in Lithuanian, the official language of the country.

Polish district administrations are particularly concerned that the Lithuanian schools are successfully competing for students with Polish schools (74). They exert all possible pressure on those Polish parents who prefer sending their children to Lithuanian schools, to transfer them to Polish schools, although in Šalčininkai district and the southern half of Vilnius district the native language of Polish children is Belarusian, not Polish. The children have to learn Polish in a Polish school. In the Vilnius district, during the 2010/2011 school year, 5167 children, or 48.8 %, were attending Lithuanian schools, 5097 , or 48.2 %, -- Polish, and 317, or 3.0 %, -- Russian schools (75). In spite of strong opposition by the Polish municipal government to Lithuanian schools, the determination of many Polish parents indicates their desire to to insure that their children will learn the official Lithuanian language well.

Moreover, there is an ongoing struggle by the parents to protect Lithuanian language kindergartens and to establish new ones. In 2010 a number of Polish and Belarusian speaking mothers demanded that a Lithuanian kindergarten be established for their children in Kalveliai village of the Vilnius district. Local and district administrations were firmly against such a kindergarten for Polish or Belarusian speaking children. Officials from the central government and deputies of the Seimas (Lithuania's parliament) visited Kalveliai, but as they were determined to avoid any confrontation with the Polish local administration, they left the mothers' pleas unanswered. However, the young Polish mothers did not give up their quest and turned for help to the Childrens' rights advocate. With her intervention the difficult struggle for the Lithuanian kindergarten in their village was resolved in their favor (76). This case became notorious throughout the country, since it exposed the timidity and disregard of duty to protect citizens' rights by high Lithuanian officials of the Ministry of Education and Science and several deputies of the Seimas.

Education and Integration

European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights in its 2010 annual report stated that "in Lithuania 42 percent of ethnic minority survey respondents indicated that they were experiencing problems in the labor market due to poor Lithuanian language skills" (77). Lithuania's Seimas and government decided to rectify this intolerable situation and, in 2011, adopted amendments to the Law on Education. In the old educational system, in all Polish minority schools every subject was taught in Polish, except for a single Lithuanian language course, and the final examination of knowledge of the Lithuanian language was less demanding than those in Lithuanian schools. As a result many graduates from the Polish schools lacked proficiency in the Lithuanian language and, therefore, had difficulty entering the labor market or matriculating in Lithuania's colleges and universities. In order to provide equal education to all children in Lithuania, the amendments to the Law on Education require the Polish schools to teach Lithuanian history, Lithuanian geography and civics in Lithuanian language and also demands that instruction in Lithuanian language must be raised to the level of the regular Lithuanian schools. The objective of the new law is to promote integration of the Polish minority into the economic, political, social, cultural, and civic life of the country (78).

This was obviously to the advantage of the Polish or Belarusian speaking youth in Lithuania. Therefore, it was an unexpected reaction of the Polish political leadership in Lithuania when it rejected the new requirements for the Polish schools. Polish leadership rejected even the concept of integration into Lithuania's society calling it identical to a forced assimilation. Petitions and demonstrations demanded that the amendments to the Law on Education be rescinded and the old curriculum for the Polish schools be reinstated (79). Actions of the Polish leadership did not get support from most other national and ethnic minorities in Lithuania, for they are well integrated into the life of the country and are in opposition to the Polish demands. The other minorities are resentful of the Polish minority since, according to their opinion, it insists on a privileged position in the country, position that other minorities neither need nor seek (80).

Polish activists appealed against the amended Law on Education to the European parliament and other European institutions. They had some success among the politicians who automatically support any complaint of a minority without examining its validity. However, the leadership of the European institutions was rather skeptical. The High Commissioner on National Minorities of the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) Knut Vollebaek stated: "I think, we also have to remind the minorities -- and this is my job also -- that there are certain obligations living in the society, for instance, to learn the state language is an obligation and it is actually in your own interest. Because how can you integrate into society, how can you get public positions <...> if you don't master the state language?"(81)

Lithuania's Polish leadership action against the amended Law on Education and against integration of the Polish minority into the life of the country can be explained by the wish to preserve a captive Polish electorate in Vilnius and Šalčininkai districts. However, the old Polish educational system, if continued indefinitely, will preserve the self-segregation of the Polish speaking people. Sooner or later it will create an alienated, disgruntled and hostile class of people who eventually may seek to resolve their isolation either by emigrating to Poland or by seeking local autonomy and eventual separation and secession from Lithuania. Therefore, the Seimas, in spite of the insistent Polish demands, considered the continuation of the old educational system untenable.

In June, 2011, the Association of Polish School Teachers in Lithuania Macierz Szkolna issued an appeal to the Polish schools and their teachers to ignore the amended Law on Education in Lithuania and urged them at the start of the new school year on September 1, 2011, to continue with the old curriculum of Polish education. It seems that, in order to avoid any unpleasant confrontations with Polish teachers and school administrators, Lithuania's Ministry of Education and Science postpones indefinitely inspections of most Polish schools. Thus it is doubtful that the amended Law on Education is being implemented in all of them. Most likely many of them still continue teaching according to the old curriculum.

Present Polish government and a large section of Polish public opinion are supporting all complaints and demands of the Polish political, educational, and cultural leadership in Lithuania (82). On March 23, 2011, Polish Foreign Ministry issued a statement that the Lithuania's amended Law on Education has caused a great disappointment and concern of the Polish minority in Lithuania, as well as upset public opinion in Poland. It asserts that this law, that requires teaching of several subjects in Lithuanian language in Polish schools, will result in a gradual destruction of the Polish system of education in Lithuania, and instead of promoting integration of the Polish minority, will result in its forcible assimilation. Bronisław Komorowski, the President of the Polish Republic, Donald Tusk, the Prime Minister, and Radosław Sikorski, the Foreign Minister, issued similar alarming statements about discrimination and intolerable conditions of the Polish minority in Lithuania. The foreign minister in particular is critical of Lithuania's policies toward the Polish minority. He often reiterates his disappointment that Lithuania does not live up to the Polish expectations.

In an interview with a Lithuanian daily Lietuvos rytas, on July 21, 2011, Mr. Sikorski conceded that in Lithuania there are more Polish schools than in any other country outside Poland. He also agreed that the Poles in Lithuania should learn Lithuanian language in order to be successful and effective citizens of the country (83). Indeed, out of 170 Polish schools outside Poland, almost a hundred are in Lithuania (84). Lithuania's ambassador in London asserts that: "... all stages of teaching, from kindergarten to university, are available for the Polish minority in Lithuania in their mother tongue. This is unique in Europe. Indeed, the branch of Bialystok University in Vilnius, ... is the only Polish higher-education institute established abroad." (85). Obviously there is no discrimination in Lithuania against national minorities in education, and members of the Polish ethnic minority enjoy exceptionally favorable conditions for learning.

There are polititians and intellectuals in Poland who oppose unfounded complains and demands directed against Lithuania's educational policies (86). However, their voice is overwhelmed by the widespread propaganda about intolerable discrimination and persecution of the Polish minority in Lithuania.

Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov and his Polish

counterpart Radosław Sikorski in 2010.

Recently, the Foreign Ministry of the Russian Federation issued a statement denouncing alleged discrimination of Polish and Russian minorities in Lithuania and affirmed Moscow's support for their demands. Thus Russia is inserting itself into the Polish-Lithuanian controversy and is taking the Polish side (87).

The Economist recently observed on Polish-Lithuanian relations: "With goodwill, the problems would be trivial. None of them amounts to discrimination, let alone persecution." (88) This raises a question: what is the real reason for the groundless complains by the leadership of the Polish minority in Lithuania and the unconditional support of these complaints and demands by the Polish government. The Polish government insists on Lithuania's acceptance of its demands which amount to micromanagement of Polish educational system in Lithuania. Obviously, allowing such interference in the internal affairs of Lithuania would severely degrade Lithuania's sovereignty and independence. Lithuanians are apprehensive about the ultimate objectives of Lithuania's Polish minority and of the government of the Polish Republic (89). Is it a secession of Vilnius and Šalčininkai districts and dismemberment of Lithuania? In 2009, Mr. Sikorski, Polish Minister of Foreign Affairs, denied that during the interwar period Vilnius was occupied by Poland (90). This statement can be interpreted as challenging Lithuania's right to its capital. Does it indicate an intention to reoccupy and reannex Vilnius? The persistent attempts to humilate Lithuania may also manifest a desire to finally consummate the 600 year old Polish dream to annex it to Poland. Such Polish project cannot succeed since Lithuanians cherish their country's independence and are allergic to any "big brother", Russian or Polish, ordering them around. Therefore, it is likely that the present tense Polish-Lithuanian relations will continue, until Poland will treat Lithuania again as a sovereign and independent country and not as a dependency of the Polish Republic.

Algimantas Gureckas

E-mail: alvirgureckas1@verizon.net

* * *

N o t e s

1. Digest of International Law (Washington, D.C.: Department of State publication 7737, 1964), pp. 297-298.

2. Before its independence in 1991, Belarus was called Byelorussia or Belorussia, Belarusians -- Byelorussians or Belorussians.

3. Digest of International Law, op. cit., "IX, Poland", pp. 340-341.

4. Ibid., "XIII, Orderly Transfers of German Populations", pp. 347-348.

5. Timothy Snyder, The Reconstruction of Nations, Poland, Ukraine, Lithuania, Belarus, 1569-1999 (New Haven & London: Yale University Press, 2003), pp. 220-222 and 225.

6. "Poland and Lithuania, Bad blood", The Economist, March 10, 2012, p. 65.

7. Gylys [Povilas Gylys]: "Varšuvos elgesys lenkiškuose Lietuvos rajonuose -- grėsmė valstybės suverenumui", http://www.alfa.lt/print/12640178/, 10/8/2011; and "J.Karosas [Justinas Karosas]. Lietuva ir Lenkija: adekvačios užsienio politikos mįslės (I)", http://www.delfi.lt/archive/article.php?id=50462256, 10/8/2011

and "(II), http://www.delfi.lt/archive/article.php?id=50544164, 10/10/2011.

8. V. Čekmonas, P. Gaučas, L. Grumadienė, "Kalbų paplitimas pietryčių Lietuvoje XX a. pabaigoje", a map in K. Garšva and L. Grumadienė, ed., Lietuvos rytai (Vilnius: Valstybinis leidybos centras, 1993), an insert.

9. "Voranava District" from Wikipedia, March 22, 2012.

10. Petras Gaučas, "Lietuvių-gudų kalbų paribio etnolingvistinė situacija 1795-1914 m." in Garšva and Grumadienė, ed., op. cit., p. 42-100.

11. Zigmas Zinkevičius, "Pietryčių Lietuva nuo seniausių laikų iki mūsų dienų" in Garšva and Grumadienė, ed., op. cit., p. 12-14.

12. Zigmantas Kiaupa, Jūratė Kiaupienė, Albinas Kuncevičius, Lietuvos istorija iki 1795 metų (Vilnius: Valstybinis leidybos centras, 1995), pp. 342-343, 375-382, and 398-399.

13. S. C. Rowell, Lithuania Ascending (Cambridge, New York, Melbourne: Cambridge University Press, 1994), pp. 72-73 and 227.

14. Zinkevičius "Pietryčių Lietuva ...", op. cit., pp.12-13.

15. S. Suž. [Simas Sužiedėlis], "Polonization", in Encyclopedia Lituanica [EL], (Boston: Juozas Kapočius, 1975), Vol. IV, p. 317 and Gaučas, op. cit., 45-47.

16. Gaučas, op. cit., pp. 46-47.

17. EL, op. cit., IV,p. 317-318.

18 Algimantas Gureckas, "Lietuvos bajorų namų kalba ir tautybė XIX a. pabaigoje" in Mūsų praeitis (Vilnius: Lietuvos Istorijos Draugija/Lietuvos Istorijos Institutas, 2001), No. 7, pp. 33-36.

19 Jerzy Ochmański, "The Eastern Lithuanian Ethnic Boundary from the Tribal Epoch to the Sixteenth Century" in Algirdas M. Budreckis, ed., Eastern Lithuania (Chicago: Lithuanian Association of the Vilnius Region,1985), pp.113-114 and 124; Zinkevičius, op. cit., pp. 14-15; and Gaučas, op. cit., pp. 45-46.

20. Valerijus Čekmonas, "Lietuvos lenkų tautinės sąmonės raida" in Garšva and Grumadienė, ed., op. cit., pp. 110-114.

21. Egidijus Aleksandravičius and Antanas Kulikauskas, Carų valdžioje, XIX amžiaus Lietuva (Vilnius: Baltos lankos, 1996), pp. 19, 23, 131-132.

22. Ibid., p. 151.

23. B. [Jonas Basanavičius], "Priekalba", Auszra, No. 1, March 1883, p. 4.

24. Gureckas, "Lietuvos bajorų ..." op. cit., No. 7, pp. 34-35.

25. Gaučas, op. cit., Table 5, p. 92.

26. Pranas Čepėnas, Naujųjų laikų Lietuvos istorija (Chicago: Dr. Kazio Griniaus Fondas, 1976), Volume I, pp. 278-283.

27. Snyder, Reconstruction ..., op. cit., p. 70.

28. Ivan L. Rudnytsky, "Polish-Ukrainian Relations: The Burden of History" in Peter J. Potichnyj, ed., Poland and Ukraine, Past and Present (Edmonton, Toronto: The Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies, 1980), pp. 4-5 and " 'Gazeta Wyborcza' apžvalgininkas siūlo Lenkijai atsiprašyti Lietuvos už Vilniaus krašto atėmimą" http://www.delfi.lt/archive/article.php?id=57471887 3/29/2012.

29. Iwo Cyprian Pogonowski, Poland, A Historical Atlas (New York: Iwo Pogonowski, 1987), "A.D. 1918-1922, Comparison of Demanded and Actual Frontiers", a map, p. 175.

30. P. Klimas, Der Werdegang des Litauischen Staates (Berlin, 1919), No. LXXXI, p. 193.

31. V. Daugirdaitė-Sruogienė, Lietuvos Steigiamasis Seimas (New York: Lithuanian National Foundation, 1975), p. 65.

32. Pogonowski, op. cit., maps pp. 174-175.

33. Ibidem, a map p. 176.

34. Alfonsas Eidintas, Vytautas Žalys, Alfred Erich Senn, Lithuania in European Politics, The Years of the First Republic 1918-1940 (New York: St. Martin's Press, 1997), p. 39 and Alfred Erich Senn, The Great Powers, Lithuania, and the Vilna Question 1920-1928 (Leiden: E. J. Brill, 1966), pp. 20-22.

35. Kazimieras Graužinis, "Lithuania's Conflict with Poland over the Territories of Vilnius and Suvalkai" Appendix 1: Suvalkai Agreement in Budreckis, op.cit., pp. 511-513.

36. Ibidem, p. 513.

37. Senn, The Great Powers ..., op. cit., p. 51.

38. Timothy Snyder, Bloodlands, Europe between Hitler and Stalin (New York: Basic Books, 2010), p. 142.

39. Ferdinand Schevill, A History of Europe from the Reformation to the Present Day (New York: Harcourt, Brace and Company, 1951), p. 753.

40. Report by the President of the Military Commission of the League of Nations, reprinted in 3 Lithuanian Polish Dispute 57 (1922) and in Algimantas P. Gureckas "Lithuania's Boundaries and Territorial Claims between Lithuania and Neighboring States" in New York Law School Journal of International and Comparative Law (1991), Vol. 12, No. 1 & 2, p. 120.

41. Gureckas, "Lithuania's Boundaries ..." op. cit., pp.120-121.

42. Ibidem, p. 121.

43. Ibidem, pp. 121-122 and 124-126.

44. Leni Yahil, The Holocaust, The Fate of European Jewry, 1932-1945 (New York, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1990), pp. 274-275 and Yitzhak Arad, Ghetto in Flames (New York: Holocaust Library), p. 27.

45. "A Memorial from the Provisional Lithuanian Committee of Vilnius to the Polish Government, September 4, 1923" in Budreckis, op. cit., pp. 522 and 529-530.

46. V. Stanley Vardys, "Aggression, Soviet Style, 1939-40" in V.Stanley Vardys, ed. Lithuania under the Soviets, Portrait of a Nation, 1940-65 (New York, Washington, London: Frederick A. Praeger, 1965), pp. 47-58; Zenonas Ivinskis, "Lithuania During the War: Resistance Against the Soviet and Nazi Occupants" in ibidem, p.68; and Snyder, Bloodlands ..., op. cit., p. 143.

47. Snyder, Bloodlands ..., op. cit. p. 192.

48. Arvydas Anušauskas "1998 duomenys", Table No. 2 in Izidorius Ignatavičius, ed., Lietuvos naikinimas ir tautos kova (Vilnius: Vaga, 1999), p. 577.

49. "Poles in Lithuania", Wikipedia, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Poles_in_Lithuania retrieved 4/5/2011, p. 5.

50. Nastazija Kairiūkštytė "Vilniaus krašto gyventojų sudėties pokyčiai 1939-1946 m." in Garšva and Grumadienė, ed., op. cit., pp. 290-293.

51. Ibidem, pp. 295-296.

52. Arūnas Eigirdas "Migracija ir visuomenės politinės nuostatos" in Garšva and Grumadienė, ed., op. cit. pp. 328-333.

53. Kairiūkštytė, op. cit., p. 295.

54. Algirdas Vokietaitis "LLKS atidaro duris į Vakarus" in Laisvės besiekiant (Chicago: LLKS Išeivijoje, 1983), pp. 243-246.

55. O. Urbonas "Lietuvos Vietinė Rinktinė 1944 metais" in Z. Raulinaitis, ed., Dokumentai Lietuvos Vietinės Rinktinės istorijai (Chicago: Vydūno fondas, 1990), pp. 289-292.

56. Valerijus Čekmonas and Laima Grumadienė "Kalbų paplitimas Rytų Lietuvoje" in Garšva and Grumadienė, ed., op. cit., pp. 133 and 135.

57. Virgilijus Čepaitis, Su Sąjūdžiu už Lietuvą (Vilnius: Tvermė, 2006), pp. 19-20.

58. Vytautas Landsbergis, Lūžis prie Baltijos (Vilnius: Vaga, 1997), p. 148.

59. Alfred Erich Senn, Lithuania Awakening (Berkeley, Los Angeles, Oxford: University of California Press, 1990), pp. 240-242; Alfred Erich Senn, Gorbachev's Failure in Lithuania (Houndmills, Basingstoke, London: Macmillan PressLTD, 1995), pp. 47-48; and Landsbergis, op. cit., pp. 147-148.

60. Landsbergis, op. cit., pp. 157 and 159.

61. The Road to Negotiations with the U.S.S.R. (Vilnius: Supreme Council of the Republic of Lithuania, 1991), Vol. 2, Document 73, p. 123.

62. Kazimieras Garšva "Lietuvos lenkų autonomijos kūrimo istorija" in Garšva and Grumadienė, ed., op. cit., pp. 314-320 and documents pp. 383-391.

63. Ibidem, document p. 392.

64. "Vilniaus krašto gyventojų ultimatumas Lietuvos AT-bai" and "TASS Reports Ethnic Opposition in Vilnius Region", Lithuanian Information Center, bulletins: New York, September 25 and 26, 1991.

65. "Lietuvos Respublikos ir Lenkijos Respublikos draugiškų santykių ir gero kaimyninio bendradarbiavimo sutartis" (Treaty between Republic of Lithuania and Republic of Poland on Friendly Relations and Neighborly Cooperation), the text, 26 April, 1994.

66. Zigmas Zinkevičius "Apie pavardžių rašymą lenkiškomis raidėmis", Voruta, No. 14, July 23, 2011, pp. 1 and 14.

67. Ibidem, p. 14.

68. Gintautas Kniukšta, Verslas & Politika/Business & Politics, interview with Valdemar Tomaševski, December 9, 2011.

69. Aldona Kačerauskienė "Vilniaus rajone daugėja vaikų, norinčių mokytis lietuviškai", Voruta, No. 22, November 27, 2010, pp. 4 and 6.

70. Katažyna Andriuškevič "Lenkijos okupacijos (1920-1939) pasekmės Rytų Lietuvai", Voruta, No. 20, October 23, 2010; Anna Komorowska "Jaunos lenkės žodis tautiečiams Lietuvoje: 'Mažumos negali tapti diktatoriais didžiajai šalies gyventojų daliai' ", http://www.lrytas.lt/print.asp?k=news&id=13153956291315081138 retrieved 9/7/2011; and Agata Bosak "Pasaka apie lenkę, kuri norėjo būti lietuve", http://www.lrytas.lt/print.asp?k=news&id=13311343931330171528 retrieved 3/9/2012.

71. Ryšardas Maceikianecas "Ponui Lukašui Mariai Abgarovičiui,Lenkijos Respublikos senatoriui", Voruta, No. 7, April 9, 2011, p. 9 and "Savaitraščio 'Przegląd' redakcijai. Tai ne pokyčiai, tai tęsinys", Voruta, No.21, November 12, 2011, p. 6.

72. Embassy of the Republic of Lithuania to the United States of America to Frank J, Spula, President, Polish American Congress, letter, March 22, 2011.

73. Danguolė Sabienė, Rytų Lietuvos mokytojų sąjunga "Rezoliucija dėl lietuvių kalbos padėties Rytų Lietuvos mokyklose", Voruta, No. 8, April 23, 2011, p. 13.

74. Kačerauskienė, op. cit., pp. 4 and 6.

75. Ibidem, p. 4.

76. Audronė Urbonaitė "Ne kiekvienam lenkui padės žavesys", http://www.lrytas.lt/print.asp?data=&k=news&id=12749346561273168064 retrieved 5/27/2010.

77. Embassy of the Republic of Lithuania ... , op. cit.

78. "Lietuvos lenkai renka parašus prieš aktyvesnį lietuvių kalbos mokymąsi", BNS, http://www.delfi.lt/archive/print.php?id=42993383 retrieved 3/10/2011.

79. Ibidem.

80. Šarūnas Černiauskas "M. Gamzajevas: V. Tomaševskis neturi teisės kalbėti visų tautinių mažumų vardu", http://www.delfi.lt/archive/article.php?id=53950891 retrieved 1/10/2012; "Baltarusiška mokykla: nenorime palaikyti nei lenkų, nei rusų akcijų", http://www.delfi.lt/archive/article.php?id=56786015 retrieved 3/15/2012; and "Vilniaus žydų mokyklos vadovas: jei ateitį siejame su Lietuva, turime mokytis lietuviškai", http://www.delfi.lt/archive/article.php?id=43292173 retrieved 3/19/2011.

81. Embassy of the Republic of Lithuania ..., op. cit.

82. Rokas M. Tracevskis "Poland's war against Lithuania over education law", The Baltic Times, April 6, 2011.

83. Marius Laurinavičius "R. Sikorskis: Lietuva netesi savo pažadų", http://www.lrytas.lt/print.asp?data=20110722&k=lr&id=akt22_a1110722 retrieved 7/22/2011.

84. Embassy of the Republic of Lithuania ..., op. cit.

85. Oskaras Jusys "Lithuania's Polish speakers", letter to The Economist, April 7, 2012, p.20. .

86. " 'Gazeta Wyborcza' apžvalgininkas siūlo Lenkijai atsiprašyti Lietuvos už Vilniaus krašto atėmimą", http://www.delfi.lt/archive/print.php?id=57471887 retrieved 3/29/2012.

87. Eglė Samoškaitė, "Lietuva pagal Rusijos URM ataskaitą: čia persekiojami čigonai, perrašoma istorija", http://www.delfi.lt/archive/print.php?id=53492209 retrieved 12/29/2011.

88. "Poland and Lithuania, Bad blood", The Economist, March 10, 2012, p. 65.

89. Virgilijus Čepaitis "Gal jau laikas 'perkrauti' lietuvių ir lenkų santykius?", Kultūros barai, No. 12, 2010, pp. 2-6; Romualdas Ozolas "Didžiausias pavojus Lietuvai -- Lenkija", Voruta, No. 9, May 7, 2011, p. 12; Povilas Gylys "Ar Lenkija turi slaptą antilietuvišką strategiją?", Voruta, No. 15, August 6, 2011, p. 14 and No. 16, August 20, 2011, p. 14; Alvydas Butkus "Lietuvos ir Lenkijos santykiai bei Vilniaus lenkų nuostatos", Voruta, No.20, October 22, 2011, pp. 1 and 14; Antanas Tyla "Rytų Lietuva ir Lietuvos ir Lenkijos 1994 m. sutarties 'Dėl draugiškų santykių ir gero kaimyninio bendradarbiavimo' grubūs pažeidimai", Voruta, No. 21, November 12, 2011, pp.1 and 10; Gintaras Songaila "Iššūkiai valstybės vientisumui: prieš dvidešimt metų ir šiandien", Voruta, No. 19, October 8, 2011, p.10; J. Karosas "Lietuva ir Lenkija: adekvačios užsienio politikos mįslės (I)", http://www.delfi.lt/archive/print.php?id=50462256 retrieved 10/80/2011 and "II" http://www.delfi.lt/archive/print.php?id=50544164 retrieved 10/10/2011; Kęstutis Girnius "Lenkija vėl moko", Draugas, No. 150, December 8, 2011, p. 3; "V. Landsbergis Torunėje: per jėgą nieko su mumis nepadarysit", http://www.delfi.lt/archive/print.php?id=53538511 retrieved 12/30/2011; and "A. Ažubalis apie santykius su Lenkija: mums nereikia 'vyresniojo brolio' ", http://www.delfi.lt/archive/print.php?id=53627409 retrieved 1/2/2012.