THE VOICE OF INTERNATIONAL LITHUANIA

|

VilNews has its own Google archive! Type a word in the above search box to find any article.

You can also follow us on Facebook. We have two different pages. Click to open and join.

|

CHRISTMAS IN SIBERIA

A story about a Lithuanian family

deported to the Lena River delta.

North Siberia, year 1942

Text: Leona T. Gustaff

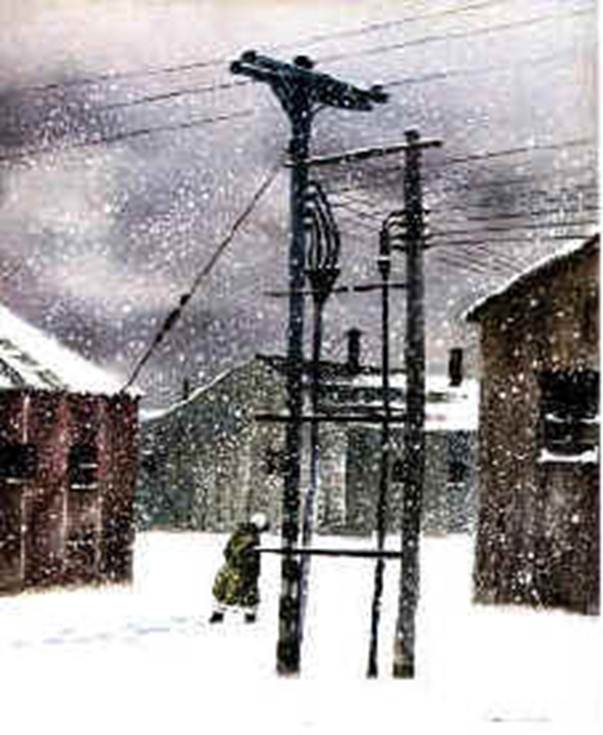

“The tents were freezing cold, harsh, and distressing; so, the adults decided to build better living conditions. "We can build barracks," said one Lithuanian, "We can catch the logs in the Lena River." The men waded barefoot into the icy water, caught floating logs, brought them to shore, and built the barracks. They covered the outside walls with snow and ice which they learned would help keep out the frigid temperature. They also found a large iron stove, which they placed in the middle of the building.”

|

Laima's Story The house was warm, secure, peaceful. The window drapes had been closed tight to shut out the rising sun. On June 14th in 1941 we were not aware of the tragedy about to enter our lives. A thick, fluffy comforter covered me and kept me safe. Tėtė and Mama slept quietly in the adjacent room. Algis, my three-year-old brother, was in sound slumber in his trundle bed. Suddenly, at 5 a.m., sharp staccato raps at the entrance of our home aroused us. "Guzevičius, wake up! Let us in! We are the militia!" Tėtė grabbed his robe and slippers and rushed to the front entrance with my Mama, brother and me running close behind. When he opened the door he encountered two men standing on the steps leading into the house. One was dressed in a Russian military outfit; the second was a friend, Dabulavičius, who lived nearby in the village of Brazavo. "Labas," Tėtė, startled and not prepared for what was to follow, greeted the men. The military man, a member of the Russian armed forces, grabbed him by the shoulders, pushed him back into the room, swung him around quickly, clasped his hands to his back, and shackled him with metal hand-cuffs. My brother and I were frightened and bewildered. We were sobbing aloud as Mama pulled at the arms of the soldier and begged him to tell her of what my father was guilty. "Dabulavičius," she pleaded, "Please tell them not to do this. Stasys has never hurt anyone. He is a good man and does not deserve this kind of treatment. He has even lent you a large sum of money recently so that you could build an addition to your home." Dabulavičius stood by silently and turned his head away so that he would not have to look at my mother. "Tylėk!" The soldier, pushing Mama aside, ordered her to be silent. "Pack whatever you think the entire family will need for a long journey. Your baggage must be less than 120 kilograms."

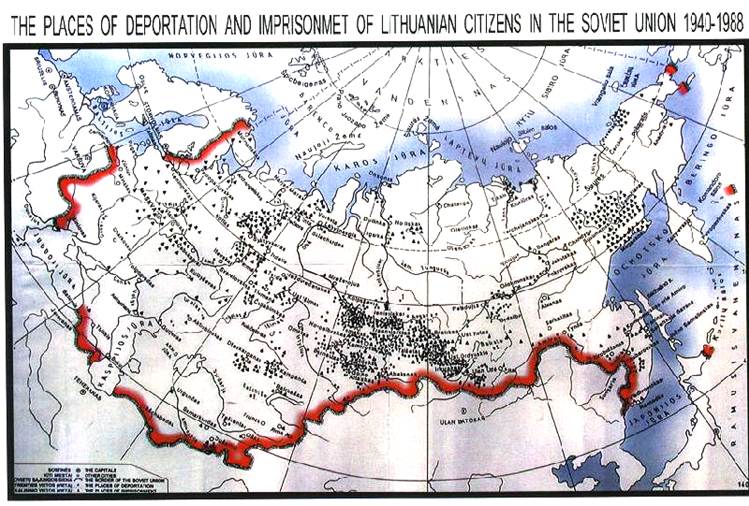

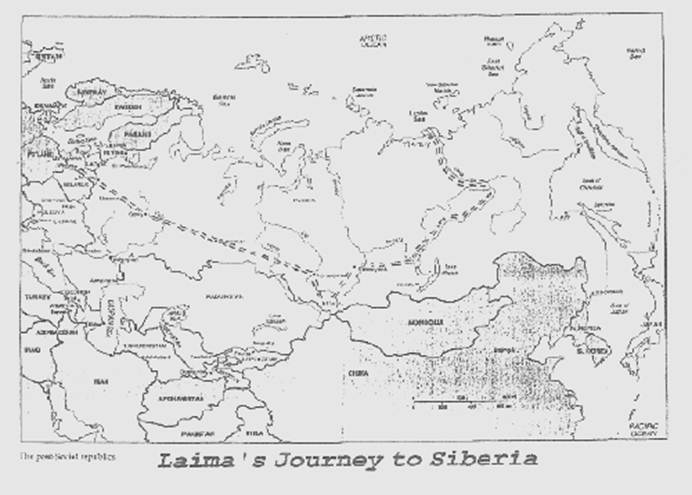

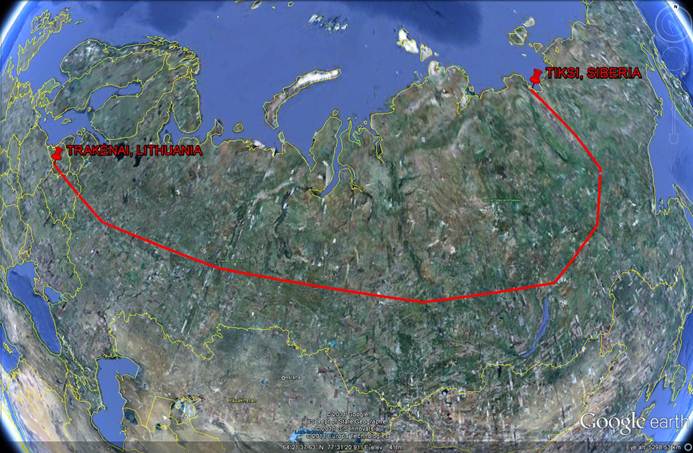

The Times At that time the Soviet Union was in total control of Lithuania. Russian military leaders were aware that 175 divisions of the Third Reich's Wermacht were advancing toward the Soviet Union's western frontier. The soldiers would have to travel through Lithuania. There had been rumors that Bolshevik militia was gathering educated Lithuanian men and army leaders to incarcerate them in prison or exile them to a foreign land. In order to receive gifts from the military or, in some instances, to save their own lives, neighbors had been approaching the Soviet officers and volunteering evidence of conversations that they had witnessed of discontent with the political regime in power. These were generally trumped up falsehoods. Tėtė then realized that his friend had conjured up treacherous untrue charges about him. Only eight days later, on June 22, the Germans attacked the Soviet Union forcing the Red Army to withdraw from Lithuania. Unfortunately, we were already on a desperate journey to an unknown destination. Tėtė, my father, was a teacher in the Kalvarijas district. He was born in 1894 in Suvalkija, not far from the town of Punskas, the third in a family of eighteen children, nine of whom were either still born or died soon after birth. He had attended Primary and Secondary schools in Lithuania, received his university education in Russia and returned to Lithuania to teach in Kalvarija. He spoke six languages -- Polish, German, Russian, French, Jewish, Lithuanian -- was the owner of an extensive library with thousands of books, and had founded and promoted new elementary schools in the Marijampolė district. Active in the community, a leader in the Kalvarija area, he had organized and taught both children and teenagers many different traditional dances. He enjoyed farming, fertilizing the land, and planting seeds to grow potatoes, carrots, and cabbage. He also propagated apple trees. He never imbibed liquor, despised alcoholics, and launched programs against alcoholism. Tėtė was 33 years old when he married my mother, who was only seventeen years of age. But Mama possessed great physical strength, loved to read, and had lively intelligent conversations with him. She and Tėtė together had purchased a home in Trakėnai from a German nationalist who was returning to his country. Trakėnai is located about five kilometers south of Kalvarija. It initially had been a large German estate, but eventually was divided into small parcels of land for German families. They bought the property, which consisted of a home and barn with land for farming. Each month they sent a sum of money to the original proprietor, who according to country laws, was the true owner until the entire amount of the sale was paid. The Beginning of the Journey Mama quickly gathered warm clothing and made small bundles for my brother and me to carry. She snatched the feather comforters from the beds and collected coats, sweaters, socks, and boots. She packed potatoes, cheese, sugar and flour, which she and my father carried. Soon, a truck filled with other Lithuanian families roared to a stop in front of our home. Mama, Tėtė, Algis, and I climbed into the back of the vehicle and searched for an area to put our hurriedly collected bags. My parents held us tight and comforted us as they wiped away our tears. The truck continued on its route until we reached Kalvarijos Railroad Station. When we arrived at the station we were surprised to see a large group of people who also carried bundles of hastily collected clothing, food, and bedding. There was noise and considerable agitation. Children cried, sobbing aloud. People talked incessantly, looked for friends, made sure certain family members were not separated, and asked each other if they knew where they were going. Everyone was frightened. No one knew the answers. Tėtė met a friend. "Ulevičius, what is happening here?" "I'm not sure, but haven't you heard the rumors?" "That educated Lithuanian men would be put into prison or exiled to Siberia? Yes, I had heard but it is difficult to believe that Communists would be so cruel." "Speak softly, my friend, so as not to be overheard. We must be careful. We cannot trust anyone." We were pushed into straight lines and commandeered into freight cars -- actually into cattle cars -- that formerly had carried farm animals from the villages to the cities. People were jammed together. Soldiers shoved more men, women, and children into already overcrowded cars. Everyone looked for an area on the floor where they could put their belongings and perhaps sit down. My parents found a small spot where we could huddle together and keep our bundles of clothing and blankets close to us.

The Train of Horrors The train began to move slowly and then picked up speed. Trapped in boxes with boarded up windows we moved through our beloved nation quickly. We could only imagine the clear natural lakes, boggy swamps, small working farms, and forests of birch, pine, and spruce trees that we passed. I don't believe any of us realized that this would be our last journey through the Lithuanian countryside for many years. How could we possibly know that some of us would never see this land again but would die and be buried in strange, inhospitable territory where we would suffer bitter cold, hunger, and absence of the ordinary needs and comforts of our existence? We were thirsty when we made our first stop at Kaunas. Crying children begged for something to drink. "Look, they're bringing water," a woman on the train shouted. She had noticed a soldier carrying a pail of water and walking towards our train. Everyone rushed to the door that was a little ajar. Mama reached out to take the pail of precious water from the soldier but he, fearing she wished to escape, angrily banged shut the door, which hit her on the head and knocked her down. She fell to the hard floor into a dead faint. "She did not awaken from this unconscious state for the next five hours." my father told me years later. Until the end of her life she had very painful headaches. From Kaunas the train began to move slowly towards the Russian border where for the first time we were given food: watery gruel and a small piece of black bread. Traveling in a daze suspended by time, we learned we were on the Trans-Siberian railway and feared we were on the way to Siberia. Years later Onutė Garbštienė, who was also deported in 1941, published her diary, which described some of the difficulties we had encountered: "Suddenly the hammering of axes echoed down the length of the train. We shuddered as if hit by a charge of electricity! They were boarding up the windows, so the "wild beasts" wouldn't escape from their cages. Some other people climbed inside. They made holes in the walls, to the outside, and also cut a hole in the floor, for our toilet. Everything was so degrading, horrifying, and shameful. Who has ever heard that men and women, crowded into this single area, had to take care of their personal needs in front of each other! We got used to the shame but not to the stench. The stench was unbearable because many, especially the children, were suffering from diarrhea caused by drinking contaminated water. Not everyone was able to make it directly into the hole. Soon the edges became encrusted with excrement. We couldn't even sit down. We started using a chamber pot, but the stench was even worse. Later we begged and were given permission to take care of this matter wherever we stopped. All shame evaporated! Everyone would squat under the cars and relieve themselves. Constipation was a problem. Suddenly: "Hurry up! Get back inside!" Everyone would run back to their assigned cars with their clothing in disarray! And this went on for the duration of the trip." Our journey lasted three weeks. Parents were exhausted. Children were tired, moody, and restless. Everyone slept on whatever makeshift accommodation they could make on the floor. Some slept on their baggage. Some were fortunate to have blankets or feather comforters. The daily ration of watery gruel and small slice of rye bread was not enough to satisfy hunger, and many were ill. The perilous trip posed severe difficulty for infants and some died in their grieving mother's arms. Soviet guards tossed them into the woods without benefit of a burial. The First Stop Eventually we reached the Altay, a sparsely populated mountainous territory in South Siberia, close to Northwest Mongolia, China, and Northeast Kazakhstan. About three times the size of Lithuania, it contains a dense pine forest, which extends into the Altay Mountains. We lived there for the entire winter. Mama and Tėtė were forced to walk about five kilometers through dark forests to the trees they were ordered to cut. The soles of their boots were worn through, and they covered their feet with rags to help them suffer the ice, twigs, and other debris they walked through on their tortuous journeys. Tėtė was not accustomed to such labor, and each evening his body was filled with pain; his fingers so frozen that he could not bend them. He longed for his library of books. Newspapers, journals, or written materials of any kind did not exist among these people. The only news we received was by word of mouth -- sometimes hopeful, sometimes sad, but always difficult to believe since the source was unknown. We were still fed only bread and watery soup. We Move On In 1942, at the first signs of summer, we were gathered into trucks and transported to the Lena River, where we were forced to clamber into large barges, heavy wired cages that had been built to transport prisoners. Armed guards patrolled us constantly. The adults again began to wonder where we were going. "Perhaps we are going to America," said Mr. Abramaičius, the father of a family we had befriended while living in Altay. We were not taken to America but instead, we entered a hellish situation; recollections of which sicken our hearts and spirits and we don't want to remember.

Slowly we sailed down the Lena River. We passed 'taiga' -- forests of pine, larch, spruce, and birch. We fought legions of biting insects, mosquitoes, and gnats. At times we caught sight of reindeer. "Those woods must be full of mushrooms," Abramaičius mentioned to my father. The thought of this delicacy that flourished in the birch woods in our native land brought a sense of sorrow and longing. We traveled until we reached Trofimovska, a fishing village on the river near the Arctic ocean, not far from the Laptev Sea. We settled in the town of Tiksi. The adults were ordered to pitch tents, the only shelter available. Winter temperature dipped down to minus 40 degree F; summers seldom reached plus 50 degree F. Our bodies were not conditioned to live in severely cold climate.

We were fortunate that Mama had taken feather comforters so that we were able to weather the cold somewhat. Others did not even have blankets. Many became ill and quite a few passed away from malnutrition and the frigid environment. Entire families died. The dead were interred in the unfriendly foreign soil. We hoped that someday their bodies might be returned to their beloved Lithuania. Daily Life Continues The tents were freezing cold, harsh, and distressing; so, the adults decided to build better living conditions. "We can build barracks," said one Lithuanian, "We can catch the logs in the Lena River." The men waded barefoot into the icy water, caught floating logs, brought them to shore, and built the barracks. They covered the outside walls with snow and ice which they learned would help keep out the frigid temperature. They also found a large iron stove, which they placed in the middle of the building. About 10 or 15 families moved with us into the barracks, but we were not destined to be comfortable very long. Soon, we were attacked by a common enemy found all over the world -- lice! We found them everywhere -- in our beds, on the floors, in our clothing. They attacked our hands, our faces, and our legs. We found them in our hair and all over our bodies. No one was safe from the lice. In Trofimovska there was nothing available to help us get rid of them. We had to kill them with our own hands. The only food available was fish from the frozen Lena River. Mama and Tėtė organized a group of Lithuanians into a fishing brigade. After drilling a few holes in the ice, they'd put bait on lines, which they lowered into the openings. They sat for hours waiting for signs that fish had snatched the bait, and we had more substantial food to add to our meager supply of bread. During the second winter in Trofimovska, weak from hunger, I was not able to walk, and I lay in bed for two months. My brother Algis was also in poor health. His teeth began to decay. More Lithuanians died from the hunger and cold. I don't know how we were saved from death. I remember that Mama sold her wrist watch to a Jakutian native for 30 kilos of black rye flour. She made 'lepioskas', and as we ate the mealy pancake we became stronger. Sometimes Tėtė still caught some fish, but eventually the Russian brigadier leader did not permit him to bring the fish home. This was our most difficult winter. We never had enough to eat, and we were always cold.

Uprooted Again In the spring, we were taken to the Siberian Islands to fish for the Communist regime. At first we lived together with the Abramaičius family in a 'yurta', a collapsible shelter built from logs and canvas. The next year Tėtė and I built a 'yurta' for our family to live in separately and alone. Tėtė began to barter the fish he caught for flour, and mama continued to make 'lepioskas'. Tėtė and Mama fished every day but they caught very few fish. Tėtė's health was failing, and he got tired very quickly. He had been diagnosed with a hernia in Lithuania. Since he was unaccustomed to the rigors of this difficult life, he suffered more intensely each day. We lived on the islands for two years when suddenly we noticed that the Jakutian native brigades were leaving the area. Fish were also disappearing; they swam elsewhere. The Jakutians had the inner sense to know when the fish would leave the islands, and they followed the fish to their new destination. The Lithuanians also began to look for ways to leave the islands. Widows with children were given permission by the Communists to go to Jakutsk, a major city almost a thousand miles south on the Lena River. Tėtė and Mama decided to travel to the Baluno region and settle in the village of Tit-Ary. We were still not far from the Laptev Sea. Tėtė spoke Russian very well, and he was fortunate to receive employment as a school manager in Tit-Ary. Native teachers taught writing poorly, and he helped many students formulate good notebooks. For the first time in our exile to Siberia I could go to school. I was so happy that I finished two years of classes in one year. We Say Goodbye In 1945, we heard that the war had ended. Tėtė wrote a letter to his brother, Joseph, who had emigrated many years earlier to America and lived in a suburb of Boston, Massachusetts. He was delivering it to the post office when he was accosted and beaten severely by Communist Commandos who resented the fact that he had a brother in the United States. Tėtė became seriously ill. He needed major surgery but the only medical assistance available to the exiles was an apprentice to a veterinarian. We made plans to search for a surgeon. Tėtė and I boarded a barge that was returning to Jakutsk after unloading food and other provisions. We sailed up the Lena River to our destination. The journey lasted one week. Since Tėtė was a Lithuanian 'tremtinys' (exile), he didn't have the necessary papers for permission to enter. When we arrived at Jakutsk, we were too frightened to go into the city. We were forced to return to Tit-Ary without the benefit of seeing a skilled physician. Tėtė's health became weaker each day. The medication given to him by the veterinarian's assistant would not relieve the pain. His concern that he was not strong enough to gather provisions for his family hastened the end of his life. Mama was devastated. Each day they conversed and planned about where she would go should his life be terminated. Although his health had deteriorated, he was a comfort to us and we looked to him for moral support. He died in Tit-Ary in 1948 and was interred there in the deep icy tundra. He was fifty four years old.

We Escape After the death of my father, Mama, Algis, and I escaped to Jakutsk, as my parents had planned. Seven years previous, when I had been seven years of age, we had been forced by the Communists to leave our comfortable home in Lithuania and travel to Siberia -- seven difficult, miserable, unhappy years for which we questioned the unfortunate circumstances which propelled us into this strange life. We reached the city of Jakutsk and were compelled to register our arrival. The general was not inclined to let us stay, and he told Mama, "If you do not find a job within seven days you must return to Tit-Ary." Jakutsk is the capital and major city of the Jakutia region. Similar to a large Soviet city, it had many schools, the Luovo Cooperative Institute, a theater, and industry that had developed during the war. Its great distance from Moscow gave it the ability to make crucial weapons and military supplies far from the impact of bombs and other artillery. The weather is the coldest in the world, and buildings are built on piles driven into the permafrost. In 1948 the majority of the population was Russian, many of which were exiles, including some from East European countries. We searched and found Lithuanian exiles who had settled in Jakutsk earlier. Willing to help us, they informed Mama about a manager at a glass factory who would hire her. Shortly after mama began to work in the factory, I was also given employment in the same building. I wanted to continue my education; so, I returned to school and finished the Tenth Form at the Middle School after completing two grades in one year. We learned to speak Russian in school and on the streets, but we always spoke Lithuanian in our home. I loved to sing and wished to study music but I couldn't get a piano; so, I entered the Jakutsk Technical Cooperative School and studied accounting. I was a good student and worked diligently. The administration advised me that I was one of two graduates with the highest scholastic marks, and I would receive a scholarship to Luovo Cooperative Institute. But Communist Security Officials informed me that I could not take advantage of the education given at the Institute. The honor was not available to Lithuanian exiles.

Hoping to See Lithuania In 1953, Stalin died and the Communists began to slowly allow children and teachers to return to Lithuania, but I was ordered to work as a bookkeeper in the city of Jakutsk. After two years I was awarded a vacation and permission to travel to Lithuania. I wrote to my father's brother, Pranas, who resided in Kaunas to tell him the good news. My Uncle Pranas was a respected Chemical Engineer who had been incarcerated in jail by the Communists for two years but never had to leave for Siberia. He invited me to stay with him and sent me the money I needed for the journey. In 1956 I was in Kaunas. I traveled on the same Trans-Siberian Railway route I had taken from Lithuania to Siberia fifteen years ago. But this time I saw the clear natural lakes, boggy swamps, small working farms, and forests of birch, pine, and spruce trees that I could only imagine on my first and only trip from the country of my birthplace. I cannot begin to explain the immense joy and pain I felt; joy that I lived to enter Lithuania again and pain that my father would never return to see his homestead, his apple trees, or the schools where he taught. If Tėtė were with me, he would not have recognized his beloved Lithuania. The ruling Soviet party dictated and controlled all public and private actions in the land. Politics, the radio, accounting, education were conducted in Russian. In the schools the Russian language was predominant. No Lithuanian was heard on the radio. Religious education was forbidden, and free expression of our native tongue, songs, and holiday celebrations was not allowed. Lithuanians worked within the Communist system in order to survive. The family home in Trakėnai had been leveled and rebuilt twice. Tėtė had given his important documents to his brother Pranas to retain in his possession when we were forcefully sent to Siberia. Unfortunately, Pranas’ home was also damaged during the war and all papers had been burned or destroyed. I wondered what would happen with our house and land. Strangers had taken residency there. Still, I preferred to remain in Lithuania. I didn’t want to return to Siberia, but my documents were only for a three-month sojourn. It was a difficult and terrifying time. A friend suggested that I lose my pass but I was afraid. I was fortunate. Uncle Pranas' wife's sister was married to a Russian General, and she urged him to petition the Chairman of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet in Lithuania, Justas Paleckis, to give me leave to stay in my country. All the documents had to be issued in Vilnius; so, I traveled there to stay with the General. He felt sorry for me, and indicated that he himself would go to Moscow to get permission for me to remain in Lithuania if Justas Paleckis refused. To my joy, I was awarded an extension of my vacation for one entire year. At the end of the year I was allowed to remain in Lithuania, but I was asked to leave Vilnius. I didn't leave Vilnius and concealed my residency by omitting to register my presence. Kipras Petrauskas, a renowned composer of music with important influential friends, admitted me into his home. I resided with his family and was warned to hide when men of the militia came to visit. Eventually, after some time, I ventured into the market place and found work as an accountant in a ‘prekyba’ (business shop). Gradually I began to work with other 'prekybas' and after thirty-six years I was the accountant for all the ‘prekybas’ in Vilnius.

A Family Reunited Three years after I had returned to Lithuania, I saved enough rubles to send for my mother. She traveled on the same Trans-Siberian railway that had taken us to Siberia. Her delight in her return to her native land was the ability to buy fresh fruits and vegetables that were difficult to purchase in the tundra. Since she learned to speak Russian in the country of her exile, she had no difficulty communicating with the language demanded by the Communist regime. But we still spoke Lithuanian in our home. Three years later my mother and I welcomed my brother to Lithuania. We all recognized that it was not the same country we had been forced to leave many years earlier. But we were in the land of our birth, the land of our ancestors. We were home among friends and relatives.

|

The face of cruelty –

Lithuania’s quisling

Antanas Sniečkus, leader of Lithuania’s Communist Party for the period 1940-1974 sent tens of

thousands of his own countrymen to inhuman suffering and death in Siberian labour camps.

Antanas Sniečkus, the first secretary of the Communist Party of Lithuania (from 15 August 1940 until his death in 1974), is said to have been the initiator of the first mass deportations of Lithuanians in June 1941. He even had his own brother, with his family, deported to Siberia, where his brother died.

Antanas Sniečkus was born in 1903, in the village of Būbleliai, 60 km west of Kaunas. During the First World War, his family fled to Russia where he observed the Russian revolution of 1917. In 1919, his family returned to Lithuania; by 1920 he was already a member of the Bolshevik Party. In the same year, he was arrested for anti-governmental activities. He was released from prison on bail, but fled to Moscow, and became an agent of the Comintern. In Moscow, he earned the trust of Zigmas Angarietis, and Vincas Mickevičius-Kapsukas, and became a member of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Lithuania. In 1926, the Comintern sent Sniečkus to Lithuania to replace the recently-executed Karolis Požėla as head of the banned and underground Communist Party of Lithuania.

From 1926 to 1930, he engaged in subversive activities in Lithuania, and was again arrested and imprisoned for them in the Kaunas Prison in 1930. In 1933, Sniečkus was released in exchange for Lithuanian political prisoners held in the USSR. In 1936, he returned to Lithuania. In 1939, he was arrested again, and sentenced to eight years in prison.

After the Soviets invaded and occupied Lithuania, Sniečkus was released from prison on 18 June 1940, and became the head of the Department of National Security. Foreign Affairs Commissar Vladimir Dekanozov, arrived in Lithuania a few days earlier on June 15, 1940, to organize the incorporation of Lithuania into the Soviet Union. As party secretary, Sniečkus issued Vladimir Dekanozov’s orders in the party’s name.

Sniečkus helped create an atmosphere of terror prior to the elections of the newly established, by the Soviet authorities, People's Seimas in July 1940. Only the Communist Party of Lithuania and its collaborators could nominate candidates. People were threatened in various ways to participate in the elections, but the results were falsified anyway. 21 July 1940 the People's Parliament, declared that the Lithuanian "people" wanted to join the Soviet Union, and 3 August 3 1940, the Supreme Soviet of the USSR incorporated Lithuania into the Soviet Union.

The process of annexation was formally over and the Lithuanian Soviet Socialist Republic was created. From 15 August 1940, until his death in 1974, Sniečkus remained the First Secretary of the Lithuanian Communist Party.

34 years of terror and atrocities against his own people had finally come to an end.

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

VilNews e-magazine is published in Vilnius, Lithuania. Editor-in-Chief: Mr. Aage Myhre. Inquires to the editors: editor@VilNews.com.

Code of Ethics: See Section 2 – about VilNews. VilNews is not responsible for content on external links/web pages.

HOW TO ADVERTISE IN VILNEWS.

All content is copyrighted © 2011. UAB ‘VilNews’.

Click on the buttons to open and read each of VilNews' 18 sub-sections

Click on the buttons to open and read each of VilNews' 18 sub-sections

Never again.

A horrible tragedy and, yes, most of the world does not know about it. We must spread the word so that something like this never happens again. Man's inhumanity to his fellow man – unspeakable atrocities happened because of it and the Lithuanians and others in the region suffered unbearably.