THE VOICE OF INTERNATIONAL LITHUANIA

|

VilNews has its own Google archive! Type a word in the above search box to find any article.

You can also follow us on Facebook. We have two different pages. Click to open and join.

|

|

Our last day in Lithuania |

|

|

|

|

|

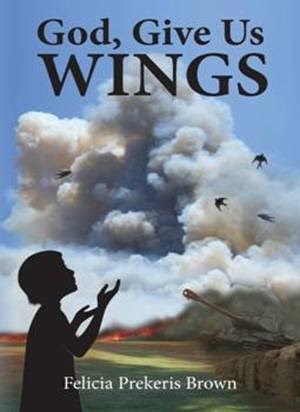

"Our last Day in Lithuania," is an excerpt from GOD, GIVE US WINGS, a riveting memoir by Felicia Prekeris Brown, of her family's struggle to survive World War II in Lithuania and then years in Displaced Person camps in Germany, until with courage and determination they achieve their dream of immigrating to the United States. |

|

|

|

|

GOD, GIVE US WINGS is available for purchase online at Amazon sites internationally.

1944, September, brought anxious nights. The low bass notes of distant artillery seemed much closer after dark. The night sky would suddenly turn white: either the Germans, or most likely the Russians, dropped magnesium parachute flares which lit up the landscape, allowing the military to see enemy positions and to reconnoiter future march routes, or select places for concealment or bivouac. Mother said of the flares, “Iškabino lempas—they’ve hung up the lamps.” I thought they were beautiful, like celestial beings descending slowly to the ground. They made my sister frantic.

My sister Milda was desperate for us to leave before fighting broke out on top of us, but our parents seemed unable to come to grips. Mother’s excuse was the coming winter. She said we did not have the right clothes to endure the cold, and she was right.

She and Mrs. Ulėnas went through every discarded rag and clothing scrap in the house to see what could be salvaged. They found a couple of threadbare jackets left by the deceased son, and patched together a winter coat for me. A torn blanket had just enough usable parts to make Milda a short jacket, but what she needed was a coat. Mrs. Ulėnas gave me an old woolen cardigan to unravel. From its threads, Mother knitted mittens for all of us. They gave us some bowls and a frying pan.

“I knew we would be forced to go soon,” said Father. “I went to the local Gebietskommissar and showed him the impressive certificate penned by his colleague to the south. They knew each other. This man wrote out a document stating that I was assigned to a temporary job teaching in Pašventys, about a mile or so from Smalininkai. I needed an official residence permit so we could register at a specific store where we could use our food coupons. That was the system: you could not buy anything unless you were registered by someone in authority at a specific store. I was making preparations to leave. I just could not make your mother come until she felt ready.”

October came and we were still at the Ulėnas farm. Early one morning, a rumbling and a roaring came pouring down the road in front of the farmstead. Soon a stream of tanks, armored vehicles, light artillery, trucks, military cars, a cavalry unit, motorcycles, horse-drawn wagons, and a long line of dust-covered Wehrmacht infantry seemed to occupy even the air we breathed. An official in the sidecar of a motorcycle pulled out of the flow and into the farmyard to smoke a cigarette. Father approached him, and in his most courteous manner, asked what was happening. “We’re on our way to defend Memel,” said he. “I don’t know how long you people here will remain under our orders. We can no longer protect Jurbarkas; it’ll fall to the Soviets very soon.”

The decision to leave or not to leave was taken out of our parents’ hands. No more delay was possible now. Father turned into a dictator and ordered Mother to pack, or he, Milda, and I would leave without her. Mother knew that the inevitable moment had come. The Ulėnases cried, but understood that we had to go. They had made up their minds to stay, hoping that the Soviets would leave them, insignificant farmers, alone. They brought out a handcart for us to take. It was soon filled with our two suitcases and the bundles of bedding, our cooking pot and frying pan, and a few dishes.

In farewell, they handed us a bag of food, which included a supply of dried bread, some smoked bacon, and a bottle of homemade moonshine. With Mother and Father pulling the handcart, we started down the verge of the road in the opposite direction from the military, heading toward Smalininkai.

We watched the military column dwindling, down to tired soldiers on foot, some horse-drawn carts carrying supplies, a few men on horseback. Father noticed a small group of cavalry riders leading three horses. A couple of the horses looked lame and worn out, but one, “a huge Swedish mare,” though swollen at the hindquarters down to her hocks, seemed otherwise healthy. Father had spent his first twenty years on a farm, and knew horses pretty well. “I ran up to the men and asked if they would let me have the mare in return for a bottle of booze. The one in charge said, ‘Let me taste it.’ He must have been pleased with it because he said, ‘Here, she’s yours.’ They handed me the lead and rode off. That mare was our salvation. Mr. Ulėnas’s schnapps saved our skins.”

I had been around many farm horses, but this mare was the biggest I had ever seen. Father was able to attach some of our bundles to the mare’s back, so now I could ride in the handcart when I got too tired. However, Mother and the horse did not like each other. If Mother came close, it tried to bite her or kick her. Milda and I stayed far away from it, well out of reach.

By noon we had made it to Smalininkai without any trouble. It was October 9, 1944. The last train from Smalininkai to Tilsit had left a couple of days before. We had delayed too long.

Missing the train from Smalininkai to East Prussia was a big blow. How would we get out now? Father had planned to sell the horse in Smalininkai for some extra food or warm blankets, and then we would ride the trains. He was counting on old friends who had farms locally to purchase the big animal. But now, with the last train gone, we would have to rely on the mare to get us away from the approaching Soviet army.

Mother and Father agreed that if we could make it to Tilsit, and if trains were still running from there to Königsberg, we might have a chance to escape to safety. However, Tilsit, on the East Prussian side of the Nemunas River, was thirty miles away, an impossibly long and tiring walk if all we could use was the handcart. We needed a proper cart that the mare could pull, plus all the equipment to harness her. When the soldiers gave her to us, all she had was a halter and lead.

In Smalininkai, Father and Mother were relieved to re-connect with a couple that they had known from 1937–1939. The Navickas family still ran a restaurant-pub, and told us we could spend the night there after the early closing hours. They had a suggestion for Father concerning a cart. They said that mutual friends, the prosperous Karvelis farming family, had departed into Prussia just days earlier. Perhaps they had left something on their property that we could use.

Father immediately went to investigate, taking the mare with him. It was not far, less than two miles away. He found the farmstead in good order, in the care of an amiable Russian prisoner of war whom the Germans had placed with the Karvelis family a year or two previously. The man was thrilled to meet someone who could speak Russian with him. “Let me show you around, and take whatever you want!” he said to Father. “I expect to be with my countrymen within days. I don’t need any of this.”

Left behind, near the barn, was a small, two-wheeled pleasure cart. Although it could hold only two persons, it was a great improvement over the handcart. Inside the storage area of the stable, Father and the Russian found a pile of worn harness parts, including a beat-up old horse collar. The two men picked through the tangle of discarded gear and cobbled together the required equipment.

Together they managed to harness the mare to the little cart, but when the moment came to pull it, she refused to cooperate. She was a German cavalry horse, unused to dragging something behind her. “She snorted and bucked and tried to rear—I didn’t know what to do,” said Father. “I stroked her and whispered sweet sounds in German. Finally, it occurred to me to bribe her. The Karvelises had left behind an ample supply of oats. I didn’t think the mare had had any for a while. I filled a nose bag I found there and let her have some. Then I took it off, and asked the Russian to walk in front, holding it out in front of her while I led her forward, still harnessed to the cart. Every few steps, when she began to spook, we’d give her some more oats. She was a very clever animal: she figured out the work-to-reward ratio very quickly, and decided the oats were worth the pulling. I suspected I’d need to bribe her again and took a big bag of oats along with me.”

By the time Father was done, it was late afternoon. He was astonished to see that during the time he had spent at the Karvelis farm, the main road leading toward the bridge across the Nemunas river had become thronged with military vehicles, horses and carts of every description, and pedestrians with bundles on their backs, or dragging loaded

The nearest crossing over the Nemunas into East Prussia was a few miles downriver from Smalininkai by way of a temporary bridge that the German military had erected near Ragnit (now Neman) when it became clear they might have to withdraw. Rumor circulated that when the Soviets got close, this bridge would be blown up to prevent them from using it.

It took Father and the skittish mare a long time to get back to the pub where he had left us. Father felt anxious about resting there overnight. He went to find out what was happening on the main road to the bridge. It was mobbed. He heard that the town of Jurbarkas had fallen to the Russians. All who could, including large numbers

The big challenge was the mare. Father had made the mistake of taking off her harness, because he had thought we would spend the night sleeping in the pub. To get her harnessed between the shafts again was close to impossible. She actively resisted. Mother had to drop everything she was doing to help Father. But the mare had decided Mother was an enemy and as she walked by, caught the top of her head between its huge yellow teeth. It bit hard, drawing blood. Mother was furious. “She’ll be the death of us!” she cried, and wondered aloud if horses carried rabies. She got some iodine from the pub owner’s wife and escaped infection, but the bite left some interesting, permanent scars.

It took Father almost an hour to calm down the mare. He had to stroke her and murmur horse endearments and repeat the

Father immediately pulled out of the throng onto the verge of the road, tethered the horse to a tree and rushed off back to Smalininkai, urging us to pray he would find the handbag. Father’s absence could not have lasted long, but our anxiety made it seem like hours before we saw him appear, worn out but triumphant. He had the handbag. “I did not think for a minute that it would be there for me to find,” he confessed, “but there it was, right where Mother had left it, untouched. One of us has a powerful Guardian Angel.” He gave Mother a big, reassuring hug.

I could tell that our parents were agitated about the slow pace of our progress. Milda kept rushing forward as though her haste could make everything move faster. She would speed ahead, then stop and wait until we caught up. Mother kept yelling at her to stay close, that we could lose her in the dark. Once she did get lost for some minutes, and even Father lost patience. She was so scared of the Soviets and the sickening stories she had heard about them that she could not wait to get to the other side of the Nemunas River, which their tanks could not cross.

German military trucks and light artillery were trying to get past the fleeing crowds, which made the congestion worse. We heard the thunder of artillery coming closer, then retreating again. We were creeping in a traffic bottleneck less than half a mile from the bridge when suddenly, a thunderous volley of artillery fire burst close by, to the north. Voices in German and Lithuanian screamed, “The Reds! The Soviets! They have broken through! Hurry! Run!” Over the noise of the explosions, you could hear screaming.

At first, everything was chaos, a dead stop, and then the pace of the fleeing masses picked up. Officious German military personnel had been checking everyone’s documents before allowing them on the bridge, but the terrorized crowd overwhelmed them and pushed them out of the way. The bridge was unguarded, and everyone rushed and shoved their way to the Prussian side. Our mare must have been used to front-line action, because the dark, the crowd, and the noise did not bother her at all.

We were in Prussia! We were across the river: we were safe! Milda was grinning ear-to-ear.

Once over the bridge, Father pulled the mare away from the pandemonium on the main road toward the nearby outline of a forest of young pines, planted not long before in regimented rows. The long, damp trek, plus the stress and anxiety of the last hour, had exhausted everyone. “Our legs had turned to jelly,” said Father. “We had to sit a while.”

As we stood under the dripping trees chewing on

The flash of explosions was our only light. We zigzagged between the trees, unsure of finding an opening wide enough to allow passage to the little cart. For what felt to us like hours, shells whistled above and around us, shaking the earth as they exploded, hurling trees and branches and clods of earth. All of us thought this was to be our end. Only the mare seemed untroubled by the explosions.

Unbelievably, we made it safely out of range of the heavy artillery. Late in the evening of October 9, 1944, we left our homeland, still believing that our exile would be temporary.

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

VilNews e-magazine is published in Vilnius, Lithuania. Editor-in-Chief: Mr. Aage Myhre. Inquires to the editors: editor@VilNews.com.

Code of Ethics: See Section 2 – about VilNews. VilNews is not responsible for content on external links/web pages.

HOW TO ADVERTISE IN VILNEWS.

All content is copyrighted © 2011. UAB ‘VilNews’.

Click on the buttons to open and read each of VilNews' 18 sub-sections

Click on the buttons to open and read each of VilNews' 18 sub-sections

Hiya, I’m really glad I have found this info. Nowadays bloggers publish only about gossip and web stuff and this is actually frustrating. A good site with interesting content, this is what I need. Thanks for making this site, and I will be visiting again. Do you do newsletters by email?

judi poker

poker online

togel singapore

Great post!

Simple but detail.

Thanks.

Catering Jakarta

Nasi Kotak Jakarta

hello all, check this account if your hobby is cook http://rajaperabotan.com/index.php/2017/12/05/pan…

Hello

this is my first visit to your site

Great your site. When i view your article and view your site have good.

I like your site.I have feel good in your content the best.

Article have good on cyber world.

Thank for sharing article

dewa poker

excellent post, I really enjoyed reading, thanks for sharing.

http://www.thegreenfoodtechie.org

My wife, Sophie (Juozapaitis) Elder came from the Taurage region and her family were also farmers. Their experience in leaving Lithuania sounds similar to your description. They were also in displaced persons camps in Germany. Sophie remembers very little since she was 3 when they left and then spent 5 years in the camp before being sponsored by a "pea canny" factory in Cleveland Wisconsin. She does remember being the "little" person to craw under the fence to get the peat to burn for heat, and she thinks the fence was the border to Poland. Her father had a picture of a group of people waiting in front of a large building that reads " Depholz". She says they were waiting for the train to take them to Hamburg to fly to the US. This was 1949. The family (boy and girl) then grew up in Sheboygan Wisconsin.

So, where can I purchase your book? We would love to read it, Sophie family have passed and in their latter years did not care to talk about it. Her father thought it would be a temporary situation also.