THE VOICE OF INTERNATIONAL LITHUANIA

|

VilNews has its own Google archive! Type a word in the above search box to find any article.

You can also follow us on Facebook. We have two different pages. Click to open and join.

|

The room assigned to us was pretty small. There was barely room for three small beds, a small table, and a small wardrobe, which was more than ample to hold our small supply of clothing. Everything was small, except our joy: the war was over, we had survived, we had our own space, and hope soared that all four of us would have a future after all. Father and Mother were still young—not yet forty; sister Milda was sixteen; and I was eight.

Christmas was approaching, but most displaced persons had not had the time or the mental leisure to arrange private family celebrations. There were no stores to buy presents, and many of us did not have anything of value to barter with the local Germans for extra food, or toys for the children. We were dependent on the basics doled out in the camp's "pantry." Each of the Baltic countries, Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania, had its own camp committees, and each was planning its own religious and patriotic program to commemorate the occasion. That would be the extent of the festivities.

Then early in December, everyone in camp learned that a few days before Christmas, there would be a special dinner for children in a certain age range, accompanied by one parent, to be held at the nearby British military quarters. How exciting: I qualified! Mother insisted that Father go with me because he was so gaunt, and she hoped there would be extra food for him.

On the appointed day, military trucks picked us up, over a hundred children and their designated parent, and deposited us at a beautifully decorated hall with an elevated stage on which stood a huge Christmas tree. Mysterious paper bags surrounded the tree. I was too excited to think about food because word went around that each child would get a gift! And that later there would be a lottery of gifts for the parents. I was hoping and praying that "Father Christmas" would give me a doll. I longed for one with my whole being.

The food was delicious: ham and potatoes, rolls and milk, and a frosted cake for dessert. Father kept wondering how to bring a piece of ham back to Mother and Milda, but realized it was hopeless. His one decent pair of pants could not survive a ham slice oozing fat in either pocket.

Our hosts put on a short program of pantomime skits, which few understood, and then sang British Christmas carols. When they started "Silent Night, Holy Night," we refugees joined in, all of us singing in our own languages. It was a rare moment of togetherness, united in the beauty of the music, a glimpse of heavenly peace never to be forgotten.

Finally! Onto the stage strode a green-clad "Father Christmas." He spoke enthusiastically but incomprehensibly in rapid English, finally directing the soldiers in attendance to distribute the paper sacks to the children. Imagine my disappointment when I saw the contents: not the longed-for doll, but a roughly made and grubbily painted paper mache figure of a blue-clad Father Christmas, shown carrying a sack of toys that we children could only dream about. Every child was crestfallen; every child made the best of it knowing that nobody had been singled out. Father thought that it would make a fine holiday decoration in our small room, and I was consoled.

Each child's sack held a slip of paper with a number. These were lottery tickets for the few items the kind-hearted soldiers had donated as gifts for the adults. As numbers were called, I noted that some parents received a bar of soap, some a penknife, others a cigarette lighter, a few a shaving brush. I was astounded to see the delight of the grown-ups with these items, being too young to appreciate their practical value, or to know how hard it was for refugees to obtain such things. And then, just as I was giving up on having my number called—it was! I could hardly sit in my seat: what would Father win? I saw him hold something small in his hand, and his face was beaming. Must be something utterly wondrous, I thought.

"Daddy, what is it?" I wanted to know, grabbing at his hand. He opened his palm. In it—a small box of new razor blades. At first I stared uncomprehendingly: this is a gift? But I had to rejoice, seeing how pleased he was. Father had a safety razor, useless without blades, which were a luxury beyond our means to obtain. I had watched him shaving each morning with a straight razor that needed constant vigorous stropping, and which left him with cuts every day. He hated that thing with a passion.

With immense devotion and care, Father made those blades last him for many months, never failing to remind me that it was my luck at the Christmas party that had relieved him from the hated strop.

* * *

Germany issued their own money!

albionfp@hotmail.com

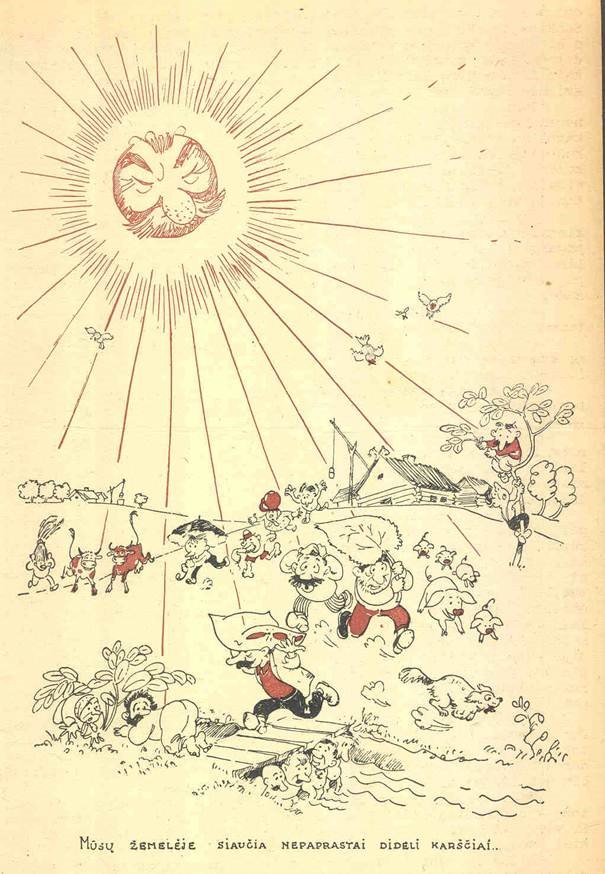

In May 1945 Europe was in shambles. With the fall of the Nazis, Germany was sliced into Allied zones, and the process of rebuilding Europe began. War and its aftermath had uprooted thousands of people from their homes and countries, and many found themselves liberated from Nazi concentration camps with no place to go.

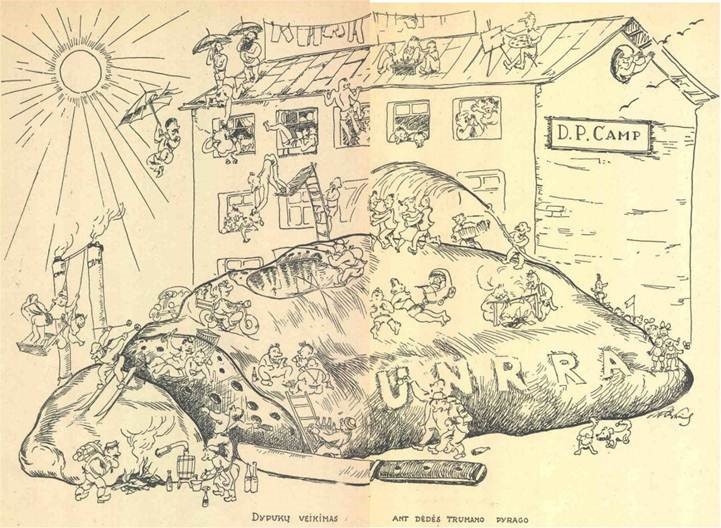

The care of refugees in Europe was handled by the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration (UNRRA) until 1947, when responsibility was transferred to the International Refugee Organization (IRO), which also was a function of the United Nations. These refugees became known as displaced persons (DPs), and the Allied powers soon realized they had a delicate problem to solve.

The Allies, including the United States, initially accused Lithuanian DPs of being former Nazi sympathizers. They later realized that the actual reason for their reluctance to return to their country was based on the fact that having witnessed the Soviet atrocities in Lithuania in 1940-41, they certainly would be executed or deported to Siberia if they set foot on their native soil. Still, to the horror of many, some were forcibly sent back by the Allies, never to be heard from again.

Gradually, western nations accepted the reality of the situation and opened their doors to large numbers of immigrants from DP camps. Many DPs made their way to new lives in the United States, Canada, Australia, Great Britain, and Argentina in the late 1940s and early 1950s.

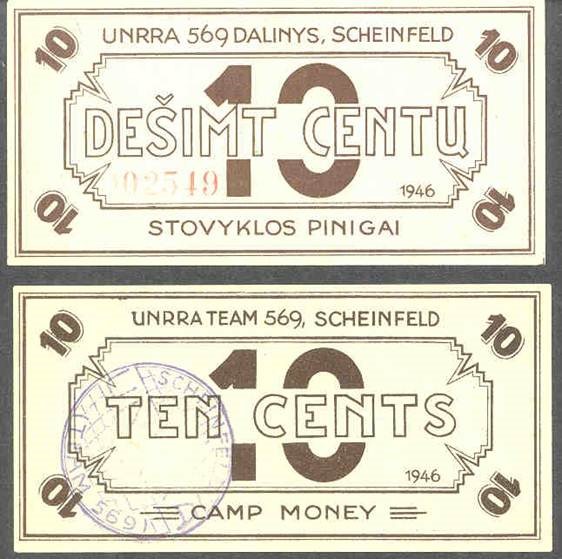

Many DP camps issued their own internal currency, which was used to pay workers and others within their confines. Generally, the money was spent at the canteen or “P.X.” for needed supplies. A virgin field for collectors and researchers alike, DP camp money has caught the attention of numismatists in recent years. Examples would sometimes appear in estates as former camp members became deceased.

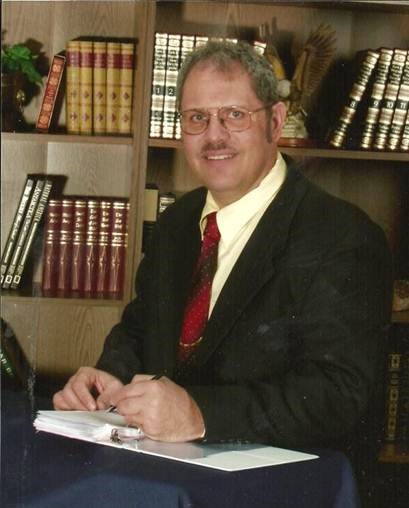

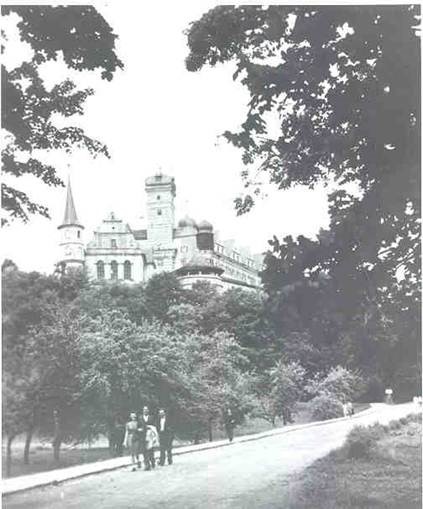

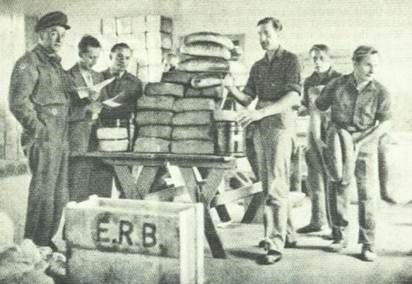

Atop a sandy slope on the outskirts of Scheinfeld, a small town in Bavaria halfway between Nuremberg and Wurzburg, sits a 17th century castle built by the Schwarzenberg family. It was in the imposing structure that a Lithuanian DP encampment was established on April 28, 1946, to house 1500 Lithuanians transferred from the DP camp in Regensburg. The camp was headed by an American reserve officer of Lithuanian descent, Stanley B. Milnus, whose parents had come from the Vilnius region of Lithuania. Chairman of the camp’s committee was Professor Ceslovas Masaitis, a Lithuanian mathematician.

Administered and occupied entirely by Lithuanians, the Scheinfeld camp was liquidated in 1949 after its administrator, Steponas Birutis, left for America. Committee chairman Masaitis later instituted a Lithuanian fraternal order in the United States that carried the “Scheinfeld” name. 1

The DP issues of Scheinfeld, Team 569, are perhaps the most familiar of the Lithuanian camp money. Originally unknown in numismatic circles, the money suddenly appeared on the market in the early 1970s, when a small hoard surfaced in England. Because the specimens were in nearly Uncirculated condition, many doubted if the money was actually put to use. Furthermore, interviews with former DPs reveal that German and military monies circulated within the camp, and no one remembered ever seeing camp money.

However, UNRRA records for the Scheinfeld camp have shed some light on the mysteries surrounding the currency used in camp. In a report dated June 15, 1946, UNRRA Team 569 Director Anton A. Pritchard stated:

In the month since the camp has been opened, the following welfare projects have been organized:

1) A camp newspaper is published daily with an English translation for the director;

2) An amenity Canteen is functioning with great success;

3) We have established an internal money system by which workers are paid and which works in conjunction with the Canteen…

Under the present Canteen System of paying workers and the anticipated cessation of American cigarettes from Red Cross parcels, present supplies of amenity items will not meet the demand, and an internal economic crisis can be foreseen. Particularly items needed are shaving soap, cigarettes, razor blades, brilliantine, hair and bobby pins, combs.

The following suggestions are respectively submitted, with the full realization of their lack of originality:

1) That amenity supplies (Canteen) be increased so that economic stability can be maintained and so that payment for working can be kept sufficiently attractive;

2) That a source of cigarettes can be found. 2

Another report, dated July 15, 1946, reiterates the creation of an internal camp money system and the scarcity of amenities. 3

Therefore it appears that Scheinfeld Lithuanian camp money was used in the canteen from May through July 1946. However, because of acute shortages of goods, opportunities to actually spend the money were greatly diminished, and the monetary system subsequently was abandoned.

It is surmised that all Scheinfeld notes were destroyed, with one authority keeping an estimated fifteen sets as souvenirs, thus accounting for the hoard which surfaced in England.

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

VilNews e-magazine is published in Vilnius, Lithuania. Editor-in-Chief: Mr. Aage Myhre. Inquires to the editors: editor@VilNews.com.

Code of Ethics: See Section 2 – about VilNews. VilNews is not responsible for content on external links/web pages.

HOW TO ADVERTISE IN VILNEWS.

All content is copyrighted © 2011. UAB ‘VilNews’.

Click on the buttons to open and read each of VilNews' 18 sub-sections

Click on the buttons to open and read each of VilNews' 18 sub-sections

Thank you, Felicia–I am adding this new chapter to your wonderful book,

and I hope there will be others.

Judith

Thank-you, Boris! It was those rare but magical moments of beauty or of kindness that made survival possible.

What a heart-warming memoir you have written, Felicia! In the aftermath of the devastation wrought by war, you and your family were able to celebrate a truly magical Christmas, stark and simple by today's standards, but filled with love, joy, and hope for the future. As I read how the refugees joined in singing "Silent Night, Holy Night" in a chorus of different languages, I could only think how beautiful it would be if we could find in our war-ravaged world of today, the calm you must have felt that night long ago.

Through your wonderful prose, you have captured for all time a remarkable episode in the saga of the nations of Eastern Europe, whose children escaped the claws of the invader, and lived to see their homelands liberated from tyranny. May the joy of your Christmas spirit spread through VilNews across the wide oceans and embrace the globe.