THE VOICE OF INTERNATIONAL LITHUANIA

|

VilNews has its own Google archive! Type a word in the above search box to find any article.

You can also follow us on Facebook. We have two different pages. Click to open and join.

|

|

IN MEMORY OF JEWISH KAUNAS |

Chiune Sugihara:

The Japanese diplomat/

spy who became a hero of the Holocaust

By Boris Bakunas, PhD

In the Year of Shame 1940, while the bulk of the German military machine was consolidating its grip on Poland, 110 French and British divisions sat idly on the Western Front, facing a token German force a fraction its size.

In the Year of Shame 1940, the People’s Commissariat for Internal Affairs, the dreaded NKVD, massacred 22,000 captured members of the Polish Officer Corps, turning the Katyn Forest into a vast mass grave.

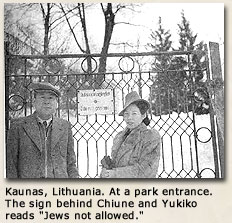

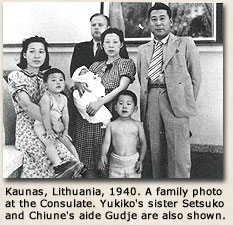

In that same Year of Shame 1940, Chiune Sugihara, a Japanese diplomat and spy stationed in Kaunas, Lithuania – along with his wife Yukiko – made a joint decision in defiance of direct orders from their government, and together they lit a beacon of hope for thousands of Polish and Lithuanian Jews. From 19 July to 28 August, 1940, the two-storey, white stucco building on 30 Vaizgantas Street that housed the Japanese Consulate, became the moral capital of the world.

Chiune and Yukiko Sugihara with their two children had arrived in Kaunas from Helsinki in 1939 not long after Nazi and Soviet troops sliced Poland into two zones of terror. Chiune’s ostensible mission was to serve as the Japanese Vice-Consul in Kaunas. His real assignment was to gather intelligence on the strength of the Soviet military in the West.

But a chance encounter at a delicatessen with an eleven-year-old Lithuanian-Jewish boy named Solly Ganor intervened, transforming the suave foreign-service officer renowned in diplomatic circles for throwing lavish parties into a hero of the Holocaust.

Jewish

refugees at the gate of the Japanese Consulate in Kaunas, July 1940.

Thousands

of Jews lined up here, hoping to receive transit visas allowing

them

to escape to the Far East and to America or Palestine.

“Now is the time to leave.”

Years later, an elderly, but healthy Solly Ganor recalled that fateful encounter.

As Solly, his hair flaked with snow, stepped through the door of his Aunt Anushka’s delicatessen in Kaunas, he saw her chatting amiably with “an elegantly-dressed man with strange, slanting eyes.”

“Ah, my dear nephew has come for his Hanukah money,” Aunt Anushka exclaimed. “Come here and meet his Excellency, the Consul of Japan, Mr. Sugihara.”

“How do you do, Sir?” Solly said.

The man shook Solly’s hand and smiled. Solly remembers taking an immediate liking to him. “There was humor and kindness in those strange eyes,” he later recalled.

Aunt Aunushka said to Solly, “You want to go to the movies, and you need a litas, right?” Solly nodded eagerly.

But before Aunt Anushka could get to the cash register, Mr. Sugihara reached into his pocket and handed Solly a shiny coin. “Since this is Hanukah, consider me your uncle.”

Solly hesitated. Then he impulsively blurted out an invitation. “Since you are my uncle, then you should come Saturday to our Hanukah party. The whole family will be there.”

The arrangements made, Solly went off to see a Laurel and Hardy film.

At six, Aunt Anushka arrived with Mr. and Mrs.Sugihara and Yukiko’s sister Setsuko at the Ganors’ apartment. Solly recalled that Mr. Sugihara wore a striped suit. His wife Yukiko, was dressed in an elegant black dress.

The Ganors had lived in Kaunas for generations. Solly’s father Chaim was a successful businessman. Among the many guests were two refugees from Warsaw, Mr. Rosenblatt and his little daughter, Lea.

The family and guests sat down at the long dinner table. Yukiko had never seen such a huge meal. There was even a duck, Japanese-style, which Aunt Anushka had specially prepared.

Mr. and Mrs.Sugihara attentively watched the Hanukkah rituals. Solly noticed that Mr. Sugihara was particularly interested in the story of Judah Maccabee, the leader of a successful Jewish revolt against foreign invaders in the second century B.C.E. He asked many questions about it.

Later, Mr. Sugihara asked Solly about his hobbies. When he learned that stamp collecting was one of them, he invited Solly to the consulate to see some Japanese stamps.

After dinner, Mr. Rosenblatt described his narrow escape from Poland and the things he had witnessed: his wife’s death during the bombings of Warsaw, Jews terrorized by Nazis and anti-Semites, arrested, and shipped off to camps. As he recounted the atrocities, Mr. Rosenblatt started to cry.

“It was painful to hear those horrible stories,” Solly recalled. “But Sugihara listened to every word.”

Later Solly overheard Mr. Rosenblatt pleading with Mr. Sugihara to issue him a visa so he could leave Kaunas. “Even a transit visa will help.”

Mr. Sugihara told Mr. Rosenblatt to come see him.

One day after school, Solly visited the consulate. Mr. Sugihara showed him into his office and pulled out an envelope from his desk drawer containing Japanese stamps. After showing him the stamps, Mr. Sugihara asked Solly a series of questions.

Had Mr. Rosenblatt and his daughter gotten their transit visas yet? How was Solly’s family faring? Solly knew that his father was hesitant about selling the family business. He couldn’t imagine Hitler invading Lithuania with Soviet troops in the country.

Mr. Sugihara’s voice suddenly sounded serious. Would Solly give his father an important message? Solly nodded. Mr. Sugihara spoke very quietly, as if he were telling a secret. “The time to leave is now,” he said.

|

|

|

|

“They all looked so sad.”

On the morning of July 27, 1940, as was his custom, Chiune rose early, ate breakfast, and climbed down the stairs to consular office below. What he saw outside his window caused him to rush back upstairs to show Yukiko.

Instead of the tranquil tree-lined street, she saw a crowd of about two hundred people, many of them dressed in bedraggled clothes.

“There were children, women, and young men,” Yukiko later said. “They were all hanging onto the fence. The young men were trying to climb over the fence. But the security of the consulate was pushing them back.”

Yukiko took several photographs. “They all looked so sad. Some women were looking right at me with great sorrow.”

To calm the throng, Chiune Sugihara agreed to meet with a delegation of five in his office. Zorach Warhaftig, a leader of Poland’s religious Zionists, was selected as head of the group. One by one the delegates described the terrible plight of the Jews. Mr. Warhaftig also told Mr. Sugihara that the Dutch consul had agreed to give Jewish refugees entrance visas for the Dutch Caribbean island of Curacao. But to get there, they would have to travel to Japan first. Would Mr. Sugihara issue transit visas for Japan?

Mr. Sugihara expressed his deep sympathy. However, he could issue only a few visas on his own authority. He told the Jewish delegates that he needed time to think. He asked them to come back the next day.

That night Chiune and Yukiko tossed and turned in a restless half-sleep. In the morning, they saw that the crowd had grown. Entire families were now sleeping on the ground, afraid that they might lose their place in line.

When Sugihara met with the Jewish delegates, the acting Dutch consul, Mr. Jan Zwartendijk, was also present.

Mr. Zwartendijk affirmed that he was willing to do all he could to help. Everybody now looked at Mr. Sugihara. Looking them straight in the eyes, Mr. Sugihara announced that he was willing to cable the Japanese Foreign Ministry for permission to grant transit visas, provided that his wife agreed.

The meeting adjourned. The first spark of hope had been struck. What had begun as a chance meeting between an eleven-year-old boy and a Japanese Consul was fast turning into a conspiracy.

Chiune

Sugihara with his wife Yukiko

“This request is a humanitarian plea.”

That evening Chiune and Yukiko descended the stairs to the consular office, where Chiune began the laborious process of encoding a cable to the Foreign Ministry. Yukiko transcribed the cable in triplicate by hand.

“I request permission to issue visas to hundreds of Jewish people who have come to the consulate here in Kaunas seeking transit visas. They are suffering terribly. As a fellow human being, I cannot refuse their requests. Please permit me to issue visas to them. This request is a humanitarian plea. The refugees’ request for visas should not be denied.”

Two days later, Chiune Sugihara decoded a cable from Japan. His urgent plea had been emphatically denied. The denial ended with the words. “No exceptions. STOP. No further inquiries expected. STOP. K. Tanaka, Foreign Ministry Tokyo.”

Undaunted, Sugihara sent a second request. The crowd of refugees, many with faces ashen from hunger and fatigue, continued to grow.

A second cable from Tokyo arrived. “Permission denied.”

Sugihara tried a third and final time. DENIED!

Wearily he went upstairs to share the bad news with Yukiko. They both knew they faced a grim, and possibly deadly choice.

If Chiune defied the Foreign Ministry’s orders, at the very least, his career would be ruined. At worst, he would be placing his life and the lives of his wife and children in peril. As Yukiko later said, “If we were in Germany, and we did something like that, my husband, myself, my children could all be taken away by the Nazis. I didn’t know what they would do to us. Maybe they’d kill us.”

Chiune looked into Yukiko’s eyes and told her that he had decided to issue visas under his own authority. Did she approve? Yes.

The next day, Chiune Sugihara had his chauffer drive him to the Soviet Embassy where he met with the Soviet consul. Sugihara spoke fluent Russian. After a brief period of negotiation, the Soviet consul agreed to allow the refugees to travel across the Soviet Union via to trans-Siberian railroad to ports along the Pacific coast where they could board ships for Japan, but at five times the standard price.

As the shiny black Buick with the Japanese flag slowly drove past the refugees outside the consulate, all eyes were trying to gauge the look on the diplomat’s face. But they saw no hint of what had transpired. The tension in the crowd grew.

Finally, Mr. Suhigara stepped out of the building and stood in front of the gate. In a calm, authoritative voice, he announced that he would issue a visa to every man, woman, and child. After a moment of stunned silence, the crowd erupted in cries of joy. Families and friends hugged and kissed.

Sugihara interviewed each refugee, asking probing questions in an attempt to find useful details to write on the visas. Each visa had to be written by hand, signed, stamped, and registered in a log containing its number and the name of the person or family who received it.

As

word spread among the Jewish community in Kaunas, the crowd in front of the

consulate mushroomed. To speed up the process Sugihara ordered his staff,

including his German assistant Wolfgang Gudze, to assist him.

“How can I handle a thousand visas?”

Among those who came to the consulate was Moses Zupnik, a yeshiva student who

looked barely out of his teens. His purpose? To obtain 300 visas for the Mir

Yeshiva, a Jewish school for religious education.

Zupnik later recalled: “I came in, and I was all excited. And I saw that he measured me. He was sitting at his desk and he was measuring me from the top to the bottom. Who I am? What I am? I said to him, ‘I am a representative of the Mir Yeshiva, and we want to go to Curacao. We just want to go through Japan.”’

Zupnik fidgeted nervously as he awaited Sugihara’s response. To his amazement, Sugihara agreed to write all 300 visas.

“I still remember when he looked at me, when he said, ‘Alright I’ll give you all the visas.’ I don’t forget these things, because they are still all alive in me. He saw people suffering, and he thought maybe he could help. And he helped.”

When Zupnik returned a few days later to pick up the visas, he found Wolfgang Gudze fraught with panic. “How can I handle a thousand visas?”

Zupnik said, “You know what? I will help you.”

When Sugihara heard about the offer, he said to Gudze, “Let him help you.”

For the next two weeks, Zupnik and Gudze worked side by side assisting Sugihara. During that time, Gudze made a deep impression on Zupnik. “He was a zaddik, a groyse zaddik” (a righteous man), Zupnik said years later.

But others reported that Gudze was a Gestapo agent

Then on 2 August, a cable from the Japanese Foreign Ministry arrived, ordering Sugihara to shut down the consulate immediately. Since the Soviets had forcibly “annexed” Lithuania into the U.S.S.R. in late July, they did not want any consulates in Kaunas. Sugihara fired off a passionate appeal to the Soviet Embassy for a delay. He was told that his request would be placed under consideration.

Sugihara speeded up the visa writing process again. Soon he was working 16 hours a day. By evening his hands ached so fiercely that Yukiko had to massage them before he could fall asleep.

On 10 August. Sugihara saw that the ever-swelling crowd now included the poorest of the poor, late-comers who lacked the connections to hear about the goings-on in the Japanese consulate. “They all seemed very tired and exhausted,” Sugihara wrote. “I did not know whether they had any place to sleep in Kaunas, maybe they just slept in the station or on the street.”

Sugihara told his staff that from now on he would issue visas even to those whose documents were obvious forgeries, even to those with no documents at all.

In mid-August, the long-dreaded reply for an extension from the Soviets arrived. Hands trembling, Sugihara slit the envelope open. Gudze heard him sigh with relief. Inexplicably, the Soviets had agreed to an extension until 28 August.

The unexpected news reinvigorated Chiune. Yukiko offered to help write visas, but he refused, firmly ordering her to stay as far away from the consular office as possible. Perhaps he didn’t trust Gudze. Most likely, he didn’t trust anybody. What he was sure of was that the responsibility for his actions should fall on his shoulders alone.

Former

Japanese consulate in Kaunas.

“Banzai Nippon!”

Then came a final warning from Japan. Close the consulate immediately and

leave. Chiune told Yukiko to start packing, while he, Gudze, and Zupnik

continued writing visas.

On 28 August, their suitcases packed and all documents burnt, the Sugihara family squeezed into the black Buick and drove off.

By this time Chiune Sugihara was worn out.

“He was so exhausted, like a sick person.” Yukiko recalled. “Even though he was ordered to go to Berlin, he said he couldn’t make it to Berlin and suggested we go to a hotel and rest before leaving.”

On the gate, Sugihara had left a note for the refugees. It said that he would be staying at the Metropolis Hotel.

Even before he could settle into his room, Sugihara got an urgent message from the hotel desk. He was needed downstairs. Having read the note on the gate, the refugees had followed him to the hotel. Sugihara wrote more visas. He wrote and he wrote until the family finally had to leave for the station and board the train for Berlin.

The refugees followed.

On the train, Sugihara continued to write visas on plain paper, signing them and flinging them indiscriminately to outstretched hands in the hope that the refugees would fill them in and find a way to outwit the Soviet and Japanese officials on their own.

As the train moved away from the station, Sugihara heard a voice shout, “Banzai Nippon!” Others joined the chorus. “Banzai Nippon! Banzai Nippon!’ These words meant “Long live Japan!” Sugihara had told some of the refugees to say this when they encountered Japanese officials.

Some witnesses reported they heard Sugihara say, “Please forgive me. I cannot write anymore. I wish you the best.”

Chiune

Sugihara memorial in Vilnius.

“I

may have disobeyed my government, but if I didn't I would be disobeying God."

Chaim Ganor never sold his business. He and dozens of other family

members, including Aunt Anushka, were sent to German concentration camps. Only

Chaim, Solly, and Solly’s sister survived.

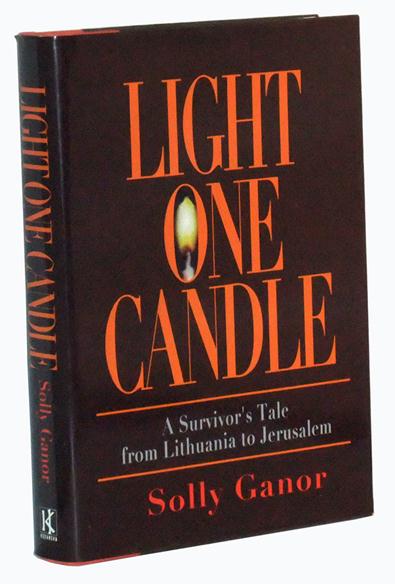

On May 2, 1945, Solly Ganor lay nearly

frozen under a blanket of snow. A four-man signal unit of the US 522th

artillery battalion was passing by, when one of the soldiers looked back and

said, “Hold it fellow, something strange is lying there in the snow.”

They found a whole group of people in striped clothing. The soldier picked

Solly up. Solly looked into his eyes and saw that they looked strangely

familiar – slanted. The soldier was Corporal Clarence Matsomura. Years later

Solly and Clarence met again in Jerusalem. In 2003, Solly Ganor’s book Light

One Candle: A Survivor’s Tale from Lithuania to Jerusalem was published.

Moses Zupnik, who came to ask Sugihara for 300 visas for the students of the Mir Yeshiva and stayed to help write visas during the two final weeks at the consulate, made it to Japan. The Japanese sent him and the other students to Shanghai, where they stayed until the war ended. Moses went to America and settled in New York City, where he became a rabbi.

Wolfgang Gudze is said to have reluctantly joined the German army. Once, when Moses Zupnik asked Gudze how he could thank him, Gudze replied. “You don’t have to thank me. But the world is a wheel. Today Hitler is on top. Tomorrow he may be down. Don’t forget what I did.” Zupnik never heard from Gudze again.

Although Mr. Rosenblatt and his little daughter Lea obtained their visas, I have not been able to learn if they survived the Holocaust.

Soon after arriving in Berlin, Chiune Sugihara was posted to Prague, where he and his family got a much-needed rest. Even so, he continued writing visas in Prague, and later in Koenigsburg, his last diplomatic post.

After the war, he and his family were detained by the Russians in one internment camp after another. The Soviet Union had declared war on Japan in August of 1945. When he returned to Japan, Chiune Sugihara was summarily dismissed from the Foreign Service in 1947. His youngest son Haruki died shortly after, but four years later a new son was born. To support his family, he worked at odd jobs, including selling light bulbs.

In 1960, because of his fluent command of the Russian language, Sugihara got a job for a trading company that did business with the Soviet Union that required him to live in Moscow. He visited his family from time to time for sixteen years until his retirement.

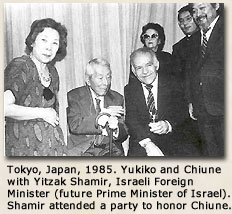

In 1968, Jehoshua Nishtri, an Israeli diplomat in Tokyo and one of the Jews Sugihara had helped save, finally tracked Sugihara down. Together with others, he lobbied the Israeli government for Chiune Sugihara’s inclusion in the Yad Vashem memorial, which was granted after extensive research, in 1985. By this time, Chiune was ill. Yukiko went to Israel and accepted the honor on his behalf. In gratitude for his deeds, Chiune Sugihara and his descendants were granted Israeli citizenship in perpetuity.

Nobody knows exactly how many visas Chiune Sugihara issued to Jewish refugees. He reported to the Japanese Foreign Ministry that he had issued 2,132 visas of which 1,500 were to Jews. It is estimated that he helped save anywhere from 6,000 to 10,000 Jews. At least 40,000 descendants of Sugihara visa-holders are alive today.

In Japan, Chiune Sugihara was honored in the year 2000 on the 100th anniversary of his birth. He had been born on January 1, 1900 – the first day of the 20th century. In 2002, a bronze statue of him was erected in the Little Tokyo district of Los Angeles in the United States.

The Polish Government posthumously awarded him the Commander’s Cross with the Star of the Order of Polonia in 2007.

In Kaunas, the Sugihara Museum now stands what used to be the Japanese Consulate at 30 Vaizgantas Street, which for a short time in the Year of Shame 1940 became the moral capital of the world.

References

Chiune Sugihara. In Wikipedia. Retrieved December 23, 2012, from http://en.wikipedia.org/Chiune_Sugihara.

Gold, Alison Leslie. A Special Fate: Chiune Sugihara, Hero of the Holocaust. New York: Scholastic Press, 2000.

A Japanese Holocaust Rescuer. Retrieved December 23, 2012, from http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=h0lizzqOxuI.

Levine, Hillel. In Search of Sugihara: The Elusive Japanese Diplomat who Risked his Life to Rescue 10,000 Jews From the Holocaust. New York: Free Press, 1996.

Paldiel, Mordecai. “Sempo Sugihara.” In The Path of the Righteous: Gentile Rescuers of Jews During the Holocaust, 252-257. Hoboken, N.J.: Ktav Publishing House, 1992.

Solly Ganor – Remembrance – Ron Greene.Com. Retrieved December 23, 2012, from www.rongreene.com/sollyintro.html.

Sugihara – The Conspiracy of Kindness. 4/6. Retrieved December 23, 2012, from http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ISsybs_89mQ.

Yad Vashem. “Visas to Japan: Chiune Sempo Sugihara.” Retrieved December 23, 2012 from http://www1.yadvashem.org/yv/en/righteous/stories/sugihara.asp.

Sugihara's widow with Lithuania's then president Valdas

Adamkus at

a tree planting ceremony in Vilnius, Lithuania in 2001.

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

VilNews e-magazine is published in Vilnius, Lithuania. Editor-in-Chief: Mr. Aage Myhre. Inquires to the editors: editor@VilNews.com.

Code of Ethics: See Section 2 – about VilNews. VilNews is not responsible for content on external links/web pages.

HOW TO ADVERTISE IN VILNEWS.

All content is copyrighted © 2011. UAB ‘VilNews’.

Click on the buttons to open and read each of VilNews' 18 sub-sections

Click on the buttons to open and read each of VilNews' 18 sub-sections

My father's cousin, Joseph Cassack, later known in the U.S. as Rabbi Zev Joseph was one of the Mir Yeshiva staff whose visa issued by Chiume Sugihara enabled him and his wife to survive. They went from Kaunas to Kobe, Japan, then to Shanghai, China, and finally to the U.S. in 1947. Rabbi Joseph officiated at my parents' wedding in 1948.

The love of humanity and moral courage shown by the Sugihara family is heart-warming.

A fascinating story! I teach junior high reading and we finish the year with a WWII unit where we examine how people respond to extreme adversity. We read about Gerda Weissman Kline and Oskar Schindler and Ann Frank and George Duckwitz (the German diplomat who facilitated the evacuation of nearly all Denmark's Jews to Sweden), but I will be adding this account of Mr. Sugihara to our study. What he (and others) accomplished was a miracle, and it was all because they had the opportunity, the humanity, and the will to try.

Thank you, Helga Burghofer, for sharing the story of how your grandmother encountered an unexpected act of kindness from an unkown Russian soldier in the Gulag.

My greatest regret after writing the article was that I was unable to include stories of the many people who helped the Jewish refugees once they embarked on their journey Sugihara visas in hand.

Professor Hillel Levine recounts many of their stories in his book ""In Search of Sugihara: The Elusive Japanese Diplomat Who Risked His Life to Rescue 10,000 Jews."

"There was a Japanese man in our compartment. I think tht he was an ambassador returning to his country" Mojsze Grynberg recalls.

During the eleven-day journey, "every time a conductor and border police would pass through the train, the [yeshiva] students would climb under the seats. The diplomat's wife would carefully carefully arrange a blanket, spreading it across the seat and down to the floor. The ambassador and his wife would return to their seats, conveniently concealing them."

Many acts of kindness were also attributed to Dr. Setsuko Kotsuiju who spent "a significant part of his family fortune in payments to officials" to ensure that the refugees were treated with consideration by Japanese police and low-level immigration officials and had no trouble in getting their ten-day transit visas extended.

When the Szepsenwol sisters arrived in Kobe, many ordinary Japanese people greeted them with baskets of fruit.

During World War II, Americans "demonized" the Japanese, even placing American citizens of Japanese descent in detention camps, where many died. Examples like these help to show the absurdity of assigning collective guilt to an entire group of people based on the actions of some of those in power.

Boris

After reading this it gives me a reason to have faith in human generosity more day. In this dog-eat-dog world where most people can’t be bothered to pick up a gallon of milk for the old widow who lives next door even if they’re going to the store anyway etc. He could have turned a blind eye like so many others did during that era, at best out of fear or worst indiference. Thank you for writing this..

Boris, you have done a fine job here. This is an incredible story of selflessness. So many stories will never be chronicled. That goes for both stories of triumph and of suffering. My grandmother, who will be 90 in a few days, often recalls the darkest days of her life. She was taken from Romania to a labor camp in Russia in January 1945 pregnant with her first child. Word had spread that the Russians were to receive laborers, but she was told not to fear as they certainly wouldn’t take pregnant women. My mother was one of few infants in that camp to survive. The stories of all wars are atrocious. Then there are stories, such as the one above, that remind us there is an upside to humanity. The most vivid part of my grandmother’s story is when she tells of how she was escorted back to camp a few days after my mother’s birth by a young Russian soldier. She struggled to walk and he carried the baby. They did not speak each other’s languages so it was a quiet walk except when the baby cried. That must have been some long walk. I have often wondered about that soldier and how many times he recounted the story, if ever.

A superb article Boris.. Aciu!!! I myself believe that in losing its Jewish citizens, Lithuania lost part of its soul.. When you look at the history of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania , filled with peoples of different races and religions, a country with just ethnic Lithuanians in it appears to be an unnatural state..Just look at the Litvak diaspora and what they have accomplished.. What would Lithuania be like today if those 200,000 citizens where allowed to live and give life to the next generations? The likes of Michael Bloomburg, Aaron Copeland, Al Jolson, Ben Bernake, Bob Dyland and so many others of that caliber…One can only weep at the loss..

Thanks for the inspiring message! My great-grandfather emigrated to the US from Kaunas in 1883, so we did not suffer the Holocaust. Nonetheless, it is part of my heritage! Blessings to Lithuania and to the late Japanese diplomat Sugihara who was instrumental in saving so many Litvak Jewish lives!

A hero and a human being at his finest. I myself believe that in losing its Jewish citizens, Lithuania lost part of its soul.. When you look at the history of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania , filled with peoples of different races and religions, a country with just ethnic Lithuanians in it appears to be an unnatural state..Just look at the Litvak diaspora and what they have accomplished.. What would Lithuania be like today if those 200,000 citizens where allowed to live and give life to the next generations? The likes of Michael Bloomburg, Aaron Copeland, Al Jolson, Ben Bernake, Bob Dyland and so many others of that caliber…One can only weep at the loss..

Didn't Lithuana come out with a postage stamp honoring him several years ago? You might like to illustrate that.

Thank you for your insightful comment, Bernard. How else can we understand Chiune and Yukiko Sugihara's courageous deed, but as "an act of love for fellow human beings"? Yes, Chiune and Yukiko "belong in the annals of history." How wonderful it would be if the government of Lithuania could do what Israel did — grant the Sugihara family perpetual citizenship in recognition of Chiune and Yukiko's courage!