THE VOICE OF INTERNATIONAL LITHUANIA

|

VilNews has its own Google archive! Type a word in the above search box to find any article.

You can also follow us on Facebook. We have two different pages. Click to open and join.

|

Litvak forum

- Posted by - (2) Comment

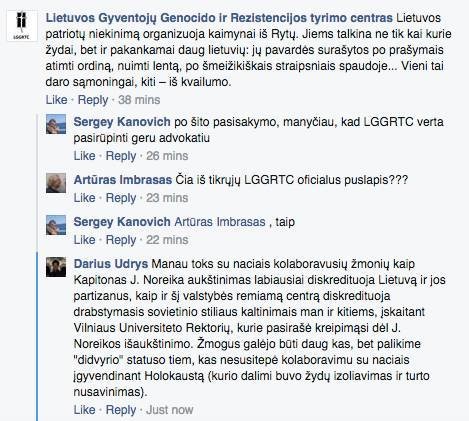

Research Centre of Lithuania

(GRRCL) insults all Jews and

decent citizens here

SERGEY KANOVICH

Photo R. Dačkaus

Journal “Veidas”

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - (1) Comment

|

and their formidable position in world history By Aage Myhre

Editor-in-Cief I have on various occasions, in several countries, asked people if they know of the Litvaks (Lithuanian Jews) and their special place in world history and in many of today's countries and societies around the world. The answer is usually negative, which has puzzled me – in view of the unprecedented and exceptional role the Litvaks have had within a very wide range of fields, in politics, economics, business and science, to prominent roles in music, movies and many other cultural fields. Go to our SECTION 9 to read more Litvak stories ... |

|

Vilnius Old Town |

The Litvaks

Jews trace their origins in Lithuania back to the days of Grand Duke Gediminas in the early 14th century, and by the late 15th century there were already thriving Jewish communities here. In time, Vilnius became known as the "Jerusalem of the North," a centre of Jewish religious learning. The Jews of Lithuania lived an intense Jewish life, and their role and influence in the major Jewish political and cultural movements were far greater than their numbers would have suggested. Vilnius became a prominent international, intellectual centre. Here there were once as many synagogues (totally 96) as churches—including the Great Synagogue, built in 1573, a vast complex of prayer spaces and schools.

|

|

|

Vilnius was like

a Mediterranean city EMMANUEL ZINGERIS: “Vilnius was like a Mediterranean city. Lithuania before Holocaust was a society of love, full of colourful life and warm interaction between people. Imagine that here, in the street we are sitting, the windows would now be open, the mothers would be shouting to their children, and the street would be filled with joyful people discussing, singing, reading and mingling in a happy crowd of friends, colleagues and visitors.”

|

|

Rabbi Eliyahu of Vilna was born in Vilnius in 1720 and died in 1797. |

“If you seek wisdom,

Vilnius is the place to go” Before WWII there was a saying among European Jews: if you are keen on earning money, go to Lodz; if you seek wisdom, Vilnius is the place to go. “I live in this city with a feeling that it does not belong to me and that I have only come here for a visit – as a human being, a poet and a Lithuanian. In this respect Vilnius could be compared only to Jerusalem. Only Jerusalem is the city of God, whereas Vilnius is the city of a dream. Trivial as it might seem, it was founded after Gediminas has a dream. It’s as if Vilnius was not created by man – you have the feeling that Vilnius has risen from the ground, from the confluence of the rivers, from the landscape – it rises on its own, possibly with some support by man. It is also in the details that the beauty of Vilnius lies. On the one hand, the Vilnius of the dream lets its citizens merely touch it; on the other hand, Vilnius sucks them in and swallows them”

|

|

Elchanan Spector (1817-1896), served as chief rabbi of Kovno, the most prominent rabbinical position at the height of 19th century Lithuanian Jewry. |

Kaunas was an

important centre of Jewish life Jews are first known to have lived in Kaunas (Kovno) as early as 1410 when they were brought forcibly as prisoners of war by the Grand Duke Vytautas. Many of those Jews were later active as traders between Kovno and Danzig (today's Gdansk, Poland). Living conditions for many Jews were squalid. In 1858, archaic living restrictions were relaxed and all but 6,000 of the city's 35,000 Jews flocked to the Old Town in search of something better. In July 1941, however, the Nazis expelled all the Jews from the town and sent them back to Slobodka. The Kovno Ghetto was thus established. Kaunas became an important center of Jewish cultural life in the latter half of the 19th century. Distinguished Jewish leaders moved here from Vilnius, the capital, to establish yeshivas. Influential thinkers also moved to Kaunas.

|

|

is more Lithuanian than Lithuania itself. |

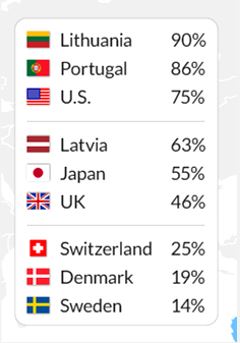

90% of all Jews in

South Africa are Litvaks It is considered that around 90% of the approximately 80,000 Jews living in South Africa are of Lithuanian descent (the so-called Litvaks), which thus constitutes the largest pocket of Litvaks in the world! You are hereby invited to learn more about this unique Jewish community that still holds Lithuania alive in their hearts, museums and synagogues. The Jewish Museum in Cape Town offers visitors a journey back in time. Most museums do. The striking feature of this museum, however, is that the journey to the past also brings us to a completely different part of our world, from Africa's southern tip to a seemingly modest little country far to the north.

|

|

(Kovno) Ghetto, Lithuania. Yad Vashem Photo Archive, 4789 |

Kaunas Ghetto (1941-1944):

An entire urban district

turned into a merciless death camp What happened to the Jews in Lithuania during World War II is a matter of grim record. Of the 250.000 Jews in 1939, only between 12.500 and 17.500 survived; of those, only about 200 remain today. It has been estimated that of the 265.000 Jews living in Lithuania in June 1941, 254.000 or 95% were murdered during the German occupation. No other Jewish community in Nazi-occupied Europe was so comprehensively destroyed.

|

|

a Holcaust survivor. . |

“I do not remember the faces of

any evil people from my past, but I do very well remember the faces of those that expressed goodness. We have to learn to love and to understand.” |

|

|

Litvaks of today

During the 19th and 20th century, tens of thousands of Lithuanian Jews emigrated to the United States of America. Many Lithuanian Jews also emigrated to South Africa which became famous as a haven for its 100.000 Jews who were spared the Holocaust. A small number also emigrated to the British Mandate of Palestine. The rise of the Nazis in Germany and the ensuing Holocaust destroyed the vast majority of Jews who had not managed to leave Lithuania and its environs.

Jews of Lithuanian origin are today in leading roles and positions around the world – some of our nowadays most famous politicians, scientists, businessmen, economists, actors, writers and singers have Litvak background. |

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - (9) Comment

State Jewish Museum, Naugarduko street 19/2, Vilnius.

16 December 2015 – 13 March 2016.

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - (11) Comment

sound that once was

"The Eternal Question” / “DI ALTE KASHE”

FRAIDY KATZ sings in Yiddish

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - (3) Comment

By Grant Arthur Gochin

California - USA

Lithuania emerged from the yoke of the Soviet Union a mere 25 years ago. Since then, Lithuania has attempted to model upon other European nations, joining NATO, Schengen, and the EU. But, has the Soviet Union left Lithuania?

During Soviet times, government was administered for the people in control, not for the local population, court decisions were decreed, they were not the administration of justice, and academia was the domain of ideologues. 25 years of freedom and openness should have put those bad experiences behind Lithuania, but that is not so.

Today, it is a matter of expectation that court pronouncements will be governed by ideological dictates. Few, if any Lithuanians expect real justice to be effected. For foreign companies, doing business in Lithuania is almost impossible in a situation where business people do not expect rule of law, so, surely Government would be a refuge of competence?

Lithuanian Government has not emerged from Soviet styles. In an attempt to devolve power, Lithuania has created a myriad of fiefdoms of power, each speaking in the name of the Government, each its own centralized power base of ideology.

Since 2013, a debate has raged within Lithuanian society about a Holocaust perpetrator named Noreika. There is no question of his guilt, his signature is on Holocaust documents, witness statements place him squarely as a perpetrator, yet honors for him remain littered throughout the country, a complete absence of morality and accountability, rather, the elevation of a bigot, a murderer and a thief.

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - (5) Comment

Letter from a Lost Shtetl

GRANT ARTHUR

PRIME MINISTER ALGIRDAS BUTKEVICIUS

By Grant Arthur

California, USA

Lithuania is changing. Clearly, my Grandfather would be proud to be here.

Nothing stays the same. Lithuania is experiencing a defined period of rediscovering its roots as an open and tolerant society. However, there is still a long way to go.

As I write on this crisp autumn morning, standing in the gentle sunlight, amongst recently restored Jewish tombstones of a lost shtetl in Northern Lithuania called Seduva, I am struck by the societal changes I see evolving.

Read more...- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - (1) Comment

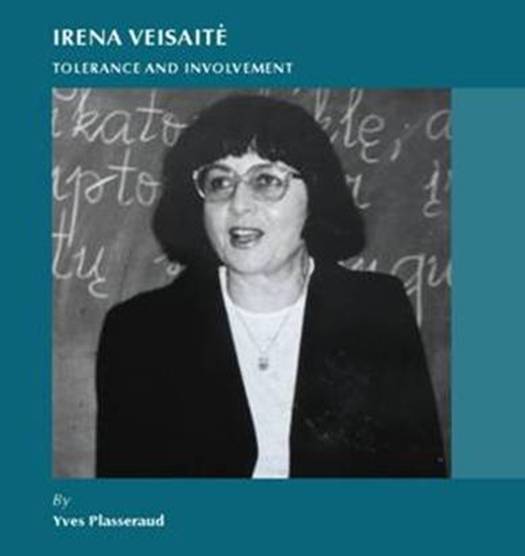

NEW book by Yves

Her intelligence

THE NEWLY PUBLISHED BOOK ABOUT IRENA VEISAITE

By Yves Plasseraud,

Paris, France

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - (1) Comment

“If you seek wisdom,

Vilnius is the place to go”

|

Adv. Marcelle Juliet Saul Sheiman, an attorney to the Supreme Court of the Republic of South Africa and Israeli advocate, who attended the World Lithuania Economic Forum in Vilnius earlier this month. Marcelle Juliet Saul Sheiman (MS) currently serves as Chairman of the Israel-South Africa Chamber of Commerce. |

Adv. Marcelle Juliet Saul Sheiman: Lithuanian Impressions 2010

15.05.2010

I am in Lithuania now and described my thoughts last night when I went along to the Shabbat dinner hosted by the Vilna Chabad Rabbi Krinsky: ones of belonging and identity.

I described these thoughts and feelings to the guests there - a community of English Jews who came as part of Jewish Journeys, a Canadian Rabbi and his wife, the Israeli now living in Lithuania and studying at its universities, and to the very elderly community members who were there (a meager amount of people). This followed the short lecture by the Rabbi as to Shavuot, and numbers - and how people were and are counted and the meaning of numbers in our life. He spoke of the being part of the Jewish people and how some no longer want to be a part of it and of the many dead.

I started telling the people about my feelings on landing in Lithuania – one of sadness in what was – the rise and fall of Yiddish civilization and how much had been and how many had lived and then also the feeling of belonging, something in me of belonging here. There was a part of me that was here.

I also very much felt a sense of belonging that night – interestingly enough juxtaposed to what was expressed by one person – his sense of alienation in Lithuania.

I may go the synagogue tomorrow. I land up doing things that I did so many years ago and am not sure of the fit anymore. How does this relate to how I am feeling today, personally? It feels strange to know that there is a time for everything, maybe because I always felt timeless. There is a time for everything and there is timelessness to everything and that includes a time to live and time to die. Who makes that choice? In what way are we G-d’s messengers and in what we do, G-d’s will? Is everything G-d’s will? Even the greatest of horrors? And then how can they be horrors?

I spoke of souls to the Rabbi last night – that I believe that when Jewish souls get too many, something happens to the Jewish people, and that our strength lies not in numbers. Everything is as it is meant to be. I question this place then of free choice and then there is this place of natural - of no decision – not to do and not not to do – where it simply is. [Maybe that is the place of free choice]. That is the feeling that I have now – is it the empty, or is it the missing? Is it the abundance or the lack thereof? There is no sense to anything in the literal meaning of sense.

IT IS SOMETIMES SO DIFFICULT TO KNOW THAT EVERYTHING CAN BE – probably because then we realize just how powerful we are - that our thoughts do create our reality; that things can lead one way or another based on our thoughts; and that we are the creators of our thoughts and lose touch with what is natural. But if our thoughts guide our reality, then anything can be so why is there so much suffering? Is it because we resist? resist what? How do our thoughts and its influence on reality have anything to do with G-d?

What is the natural way of things?

I looked at the Rebbitzin last night . She looks young, people say and she has 10 children. She is probably younger than me. I see her beautiful children. When I said to the Rabbi – wow you have 9 children (as I thought) he said – 10, but who is counting. I remember and recalled for him the story of the Palestinian woman whom I met and who was called Enough.

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

I went to the Choraline Synagogue yesterday (Shabbat) – the only synagogue left standing in Vilna. I started off my day by going into the Vilnius cathedral, a huge white marble cathedral opposite my hotel. I then walked down the streets on the way to the synagogue. Magnificent little coffee houses and medieval architecture and then arrived at the Gates of Dawn - very ornamental, gold, Christian - making my way through them to another part of the world it seemed. A part that is old, decrepit and run down, in the direction of the synagogue. It had locked gates but I managed to get in with the help of an elderly man that was also entering. There is a bell though.

I took a prayer book and sat down in the section separated for women by a lace curtain. I started praying and crying – an overwhelming feeling of being in a place which in my imagination had been filled with so many people. I could imagine my family and then - all of them being killed. Maybe herded in this shul before being taken off somewhere to die. Life and death together. I could feel the death so palpably interwoven with the life.

The Cantor's wife - came to talk to me. She had on what seemed to be a beautiful short wig. She struck me more like a beautiful doll. She told me of herself, her family. Whereas the Chabad rabbi had told of 1000 people at his Seder, she tells me of the dying community - mostly assimilated or very old. There are these two old women praying in the Shul. They must be in their 80’s. they must have been very beautiful and still seem as such – blond but with hunched backs and walking sticks. I wish them Shabbat Shalom and they smile at me through their toothless mouths. There is also this Rabbi (brought in from outside the community) with a menacing look - a huge beard and everyone seems to be a bit frightened of him. He peers through these round rimmed spectacles and rants and raves in the Shul. I walk on through the Jewish quarter with the UK crowd of people I met Friday night at the Chabad rabbi. We are doing a walking tour - the one concentrating on the life that was – the Vilna Gaon, the scholastic dynasty. Later on a tour will be taken in the same parts - the ghetto and the Holocaust. The Rabbi who is guiding the UK troupe on its Jewish journey says that it is very confusing to do the Life and Death parts together. I leave them after a while to go off to Trakas castle on my own.

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

I take a guided tour to Trakas on Saturday afternoon. The guide, a young Lithuanian woman is amazed to hear that as a Jew from South Africa and now in Israel, I had grandparents born in born Kovna (Kaunas) and Ponevys. On the way to this beautiful castle we pass Ponerai. There is such beautiful countryside, farms, trees amidst the difficult pictures I have in my mind.

+++++++++++++

16.5.10

This is a beautiful country – they look like cherry blossoms on the trees, I think they may be apple. And then the little beginnings of pines. Everywhere. A land soaked with blood. It is a big country here – once spreading from the Baltic to the Black sea. There is a declining population and it has a different energy to the one I know in Israel. The Jewish community is also dead.

+++++++++++++

17.5.10

I went for a walk this morning to find the Green House. I eventually found it, confusing it originally with the Museum for Genocide Victims, based on Russian atrocities on the Lithuanians during their occupation. I walk up a small hill and make my way there through a 7 roomed little house. You ring a bell and a woman answers. The first exhibit that strikes me is an excerpt from the “Jaeger report”. I copy it down:

Secret Reich Business:

I consider the Jewish action more or less terminated as far as Einsatzkommando 3 is concerned. Those working Jews and Jewesses still available are needed urgently and I can envisage through the winter will be required even more urgently. I am of the view that the sterilization programme of the male worker Jews should be started immediately so that reproduction is prevented. If despite sterilization a Jewess becomes pregnant, she will be liquidated.

Today I can confirm that our objective to solve the Jewish problem of Lithuania has been achieved by EK3. In Lithuania, there are no more Jews apart from Jewish workers and their families.

These total: In Schaulen c4,500

In Kauen c15,000

In Wilna c15,000

I copy down other references to Stahlecker ‘s Reich secret document on Jews. A poem – Never Say by Hirsh Glik. A reference to a book by Solly Ganor – Light One Candle. Rabbi Ephraim Oshry’s - The Annihilation of Lithuanian Jewry (translation by Y. Leiman).

I have come to the museum although I did want to follow the life of the Jews not so much for their deaths as for their life. But I find them so inextricably interwoven in this place. I read a letter from a woman to her brother in South Africa just before she and as she says – her babies are going to be killed. She is writing to her brother and tells him that her husband has been killed and now she and her children are about to be killed. She asks for blood to be avenged. I read and write various things and some are too sickening to read, so I don’t. I exit the museum and am met by the Cantor's wife. She is in pants this time and dons that beautiful - what seems like – coiffed wig. She takes me home - we meet her husband who is on the way out to get a cucumber for our meal. We walk up the stairs and she kisses the Mezuza on the inside of the house. Don’t you have mezuzot on the outside of the door - No she says – it is too dangerous. Even her husband wears a cap and not a skullcap. His beard also sometimes arouses speculation. He comes home and we talk. I ask him why he still lives here. He is from Minsk. He tells of his wife’s elderly parents but this is not the only reason – he belongs here he says. In this place where the Vilna Goan and a thriving Jewish community lived. It is not always necessary to follow the Kehila he says, even though living amongst a Kehila is also important. There are only old Jews here he says - they come to Chabad and to the synagogue for help. The rabbi who I described already - he says - comes to take the services.. This Cantor is a man who opens the heavens with his singing and comes from generations of Hazans.

We speak of Israel and I mention the calling for our spirit as Jews. And he quotes from psalms – a piece which reiterates the sentiment that the Jewish spirit is the shtetl Jew and we sit and talk and I eat. Would you believe.. Herring, Chopped Herring - just as I know it is made – with apple, and onions and eggs. It feels like home. His wife has set us a feast of chopped herring, bread, cheese, eggs for me, coffee and for me especially she brings out the Amarula – South African liqueur. She accompanies me back to the hotel, past a few more of the forgotten Jewish sites. I tell her that I learnt there was only one tree in the Ghetto – I wonder where that tree is?

I find myself attracted to her vivacity, her liveliness and that of her husband. I am Lithuanian, a Lithuanian Jewess it feels. I don’t feel loved and am wary of being the outsider but in many ways as with the Cantor, we belong.

19.05.2010

I wake up this morning with a frightened feeling. This is not Vilna, this is Kaunas - Kovna for me. This is what the guide on Saturday called the dead place. The bus ride to Kaunas brings me to a station which is replete with older cars, townspeople, something that reminds me of the towns or other cities in South Africa – not Johannesburg. There is even one man dressed in complete Russian soldier attire. It really feels strange – I see lots of open spaces, greenery, places where I have a sense one could have hid a lot of bones. My imagination.

What was here before? I want to be able to trace back the life and I feel frightened because somehow I feel alienation here [Yet from my few experiences since arriving here, the people appear friendlier than in Vilna]. Then I sit down at breakfast and in another moment I taste the way the omelets are made and I want to tell my father that no wonder he makes such great eggs. He obviously must have learnt that from his father. Does he remember what he ate way back when he was a little boy. Maybe his dad cooked for him. I have to learn to make omelets the way they do here.

I walked quite some way yesterday just to find and then touch some vestige of Jewish life. I come to the Synagogue. The gate is open and I ring the bell. A man who speaks Yiddish lets me in and I take pictures. I am reminded of the Jewish rivalries between the various synagogue factions and am told that “Kalmanowitz” you know, the mafia one from Moscow who was killed, is/ was a part of this synagogue. My "Zeida" on my father’s side was an atheist and a communist, a “difficult” man who was at once, a great artisan being able to carve the most beautiful pieces of wood and at same time, a man who could kill to protect his family. I think at once of the Jews. Those people of whom the Baal Tefila spoke. And I realize just how strong these Jews were. They were educated and strong in spirit. Who has the audacity to say that they went like sheep to the slaughter. Are these the same Jews that have guns and tanks – not that we shouldn’t have guns –– but there is strength in spirit.

I think of modesty and realize the gift of simplicity and modesty. Something it seems I have forgotten or with which I am not in touch in my milieu. Too much money, big houses. This place seems denuded of money. It is very much country. I think of my yesterday’s reading up on the flag of Lithuania – Yellow, Green and Red. The colours of the Lithuanian flag – Yellow, green and red – represent sum, light and prosperity; the beauty of nature, freedom and hope; and earth, courage and blood shed in defending Lithuania’s independence. At the moment it has been only green and red for me.

Vilnius – some excerpts:

Before WWII there was a saying among European Jews: if you are keen on earning money, go to Lodz; if you seek wisdom, Vilnius is the place to go.

“I live in this city with a feeling that it does not belong to me and that I have only come here for a visit – as a human being, a poet and a Lithuanian. In this respect Vilnius could be compared only to Jerusalem. Only Jerusalem is the city of G-d, whereas Vilnius is the city of a dream. Trivial as it might seem, it was founded after Gediminas has a dream. It’s as if Vilnius was not created by man – you have the feeling that Vilnius has risen from the ground, from the confluence of the rivers, from the landscape – it rises on its won, possibly with some support by man. It is also in the details that the beauty of Vilnius lies. On the one hand, the Vilnius of the dream lets its citizens merely touch it; on the other hand, Vilnius sucks them in and swallows them”

AIDAS MARCENAS poet

Market day in Vilnius

The soul of a bearded Jew

Is weighing memory

SIGITAS PARULSKIS

POET and WRITER

There is only one Jewish house of prayer in Vilnius at present. Not too long ago, however the Lithuanian capital was called ‘a city of a hundred synagogues’. On the even of WWII, Vilnius, which was then called the Jerusalem of Lithuania, had over 110 Jewish houses of prayer, the majority of which were destroyed during the war.

“I sometimes think that Vilnius was invented by a jolly maiden, that it is a dream she dreamed about – the flood, the boats, the two rivers, the mountain and the temples, lots of temples and little streets.

In the evening, when people disperse into their homes, and darkness walks the streets of Vilnius, I see how, in the shelter of their sleeping houses, their dreams alight – the dreams about something different, about how good it would be if it could be. Wrapped in silence, the streets of Vilnius… are dreaming.

Vilnius speaks with every stone of its cobble roads, every window bathed in soft light at night, every roof of a church, the happy laugh of students: once we were here, it was here that we that we were happy and sad, we built, we searched, we lost and found our path again. I myself am dispersing into the streets and the faces of passerby, I start flickering among the leaves of trees in the park and become a tiny part of the big dream of Vilnius…

They say that there are no stairs to heaven. Yet I can feel them here. Oftentimes in a narrow land, an old courtyard, in the glance of a passerby, in the sweet aroma of fresh bread rolls lingering in the air after the bakery opens in the morning. Sometimes autumnal leaves brush against them gently and whirl upward to our cherished dreams.”

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - (0) Comment

90% of all Jews in

South Africa are Litvaks

Text and photos: Aage Myhre

It is considered that around 90% of the approximately 80,000 Jews living in South Africa are of Lithuanian descent (the so-called Litvaks), which thus constitutes the largest pocket of Litvaks in the world! You are hereby invited to learn more about this unique Jewish community that still holds Lithuania alive in their hearts, museums and synagogues.

The Jewish Museum in Cape Town is more Lithuanian than Lithuania itself.

The Jewish Museum in Cape Town offers visitors a journey back in time. Most museums do. The striking feature of this museum, however, is that the journey to the past also brings us to a completely different part of our world, from Africa's southern tip to a seemingly modest little country far to the north, to a country where around 90% of South Africa's Jewish population has its roots (there are today about 80,000 Jews in South Africa).

The museum's basement is dominated by a village environment (shtetl) from the late 1800s. A few houses are reconstructed in full scale, and you can clearly see how people lived and co-existed at the time. The village is called Riteve. It was recreated in the museum on the basis of entries made in the 1990s by a group of experts who went from South Africa to Lithuania to find traces of the family of the museum's founder, Mendel Kaplan.

The village is called Rietavas in Lithuanian. It is there to this day, less than a half hour drive from Klaipeda, at the highway direction Kaunas and Vilnius. The Kaplan family emigrated from here in the 1920s, while the village's population was still 90% Jewish. Today, no Jews live in Rietavas.

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

Sad fate of wooden synagogues in Lithuania

- Posted by - (0) Comment

Inside of former synagogue. Used for storage (Photo: AFP)

Lithuania's wooden synagogues, the vestiges of a Jewish presence which was wiped out in the Holocaust, are falling into ruin from a lack of funding and support.

Hidden behind a row of houses, the wooden synagogue in the eastern town of Alanta looks more like a barn than a former house of worship.

This rundown building, which served as a fertilizer warehouse during the days of state farms, is now used for storage by Algis Jakutonis, a farmer living next door.

"I store my stuff there, and we still find traces of the Soviet era," said the 60-something Jakutonis, while displaying the large iron key to the former synagogue, which he acquired before Lithuania's independence in 1990.

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - (1) Comment

Israeli President Shimon Peres invited to head the advisory board for restoration of the Vilnius Great Synagogue

The government of Lithuania asked Israeli President Shimon Peres to head the international advisory board for the restoration of the Vilnius Great Synagogue.

“The [restoration] project is an important part of the effort to both preserve and restore Vilnius’ Jewish heritage, and I think that President Peres could bring valuable guidance and insight to our project,” Vilnius Mayor Arturas Zuokas said, according to the Baltic Review news site.

The comprehensive restoration and construction project could be completed as early as 2017, according to Tuesday’s report.

The offer came during a visit to Israel this week by Zuokas and Lithuanian Minister of Foreign Affairs Linas Linkevicius in which they met with Peres.

If Peres agrees, he would join Lithuania’s former President Valdas Adamkus, current Prime Minister Algirdas Butkevicius and the prominent architect Daniel Liebeskind, who are all members of the board.

The Great Synagogue in Vilnius was an icon of Lithuanian and Eastern European Jewish culture before it was ruined during World War II and demolished in the 1950s. From the 16th through the 20th centuries, it was among the best-known synagogues in Central Europe.

Read more...

___________________________________________________________________________________________

The Great Vilna Synagogue

The Great Synagogue of Vilna which once stood at the end of Jewish Street in the centre of Vilnius (where today’s courtyard between Vokieciu Street and Stikliu Street is located), was built between 1630-1633 after permission was granted to construct a synagogue from stone. Standing on the spot of an existing synagogue built in 1572, the site had first been used to house a Jewish house of prayer in 1440.

According to legend it was so magnificent and impressive, Napoleon who stood on the threshold of this synagogue in 1812 and gazed at the interior was speechless with admiration. The synagogue had a number of entrances. One, at street level, consisted of a pair of iron gates which, had been donated by a tailors’ society in 1640. The other entrance on the western side, added in 1800, was a bit more imposing. An elevated two-tiered wooden gable with a portal and wrought iron posts. There was a heavy iron door with an original Hebrew inscription indicating it was a gift of a "society of Psalm reciters" in 1642.

Read more...

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

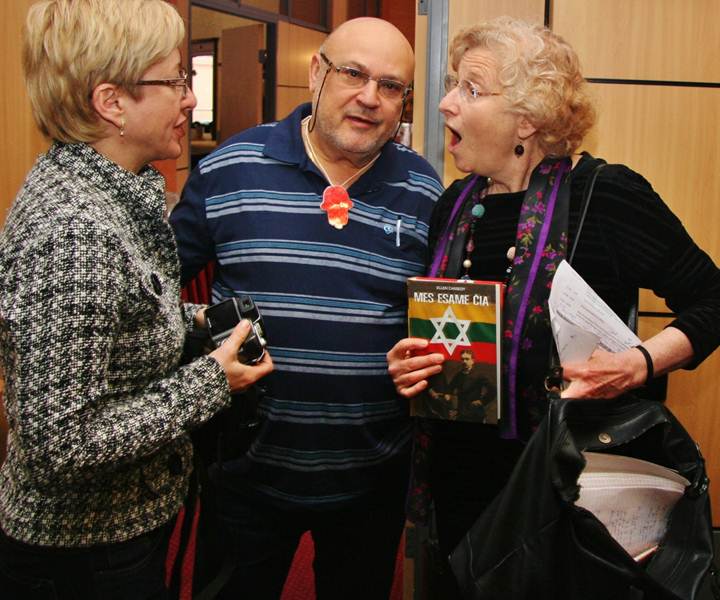

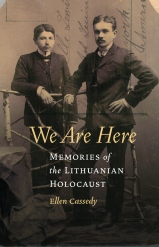

Author Ellen Cassedy in her ancestral homeland

- Posted by - (7) Comment

The

U.S. author of the book "We are here" (Mes esame čia), Ellen Cassedy

(right), was in Lithuania last month. Here in eager discussion about Jewish

life in Lithuania before the Holocaust and now today.

|

Below: Ellen Cassedy’s report from her visit to Lithuania |

|

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - (1) Comment

‘Lincoln’s’ grandfather

was a Lithuanian Jew

Daniel Day-Lewis has received widespread critical acclaim for his

performance in the movie Lincoln.

VilNews has previously written that Hollywood largely was created by Litvaks, the Lithuanian Jews who have had so endlessly huge influence on world culture, science, business and politics.

Go to our VilNews Section 12 for case examples.

Now it turns out that the star of this year's major film, Lincoln, also has Lithuanian ancestry. And not only that; his Lithuanian grandfather, Michael Balcon, had enormous influence on the British film industry in its startup phase in the early 20th century.

His mother, Jill Balcon, was a leading English film and radio actress.

Sir Michael Balcon (1896 – 1977) grandfather. |

Jill Balcon (1925 – 2009) mother. |

About Sir Michael Balcon

Michael Balcon is considered one of the most important figures in British Cinema. It was his vision that brought international prestige to Gainsborough in the 20s and 30s. and he was a vigorous spokesman for the industry for most of his career.

Michael Balcon's career began in Birmingham in 1920, where, with Victor Saville he was a film distributor. Within two years they had begun producing feature films in London - Woman to Woman 1923 was the first. He formed Gainsborough Studios the following year. He visited the Ufa studios in Berlin in 1924 and began a co-production association with The Blackguard that was to last 10 years. German technical staff populated Gainsborough films through the 20s and early 30s giving them a slick, sophisticated veneer to match any film produced in Hollywood, Balcon was aiming for a product of international interest unlike many other British studios in the silent and early talkie era.

Read more: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Michael_Balcon

About the movie “Lincoln”

Lincoln is a 2012 American historical drama film directed and produced by Steven Spielberg, starring Daniel Day-Lewis as United States President Abraham Lincoln and Sally Field as Mary Todd Lincoln. The film is based in part on Doris Kearns Goodwin's biography of Lincoln, Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham Lincoln, and covers the final four months of Lincoln's life, focusing on the President's efforts in January 1865 to have the Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution passed by the United States House of Representatives. Lincoln premiered on October 8, 2012, at the New York Film Festival, and has since received widespread critical acclaim, with major praise directed to Day-Lewis' performance. In December 2012, the film was nominated for seven Golden Globe Awards including Best Picture (Drama), Best Director for Spielberg and winning Best Actor (Drama) for Day-Lewis. The film has been nominated for twelve Academy Awards, including Best Picture, Best Director for Spielberg and Best Actor for Day-Lewis.

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - (1) Comment

Kaunas Ghetto (1941-1944):

An entire urban district turned into a merciless death camp

Two children in the Kaunas (Kovno) Ghetto, Lithuania.

Yad Vashem Photo Archive, 4789

What happened to the Jews in Lithuania during World War II is a matter of grim record. Of the 250.000 Jews in 1939, only between 12.500 and 17.500 survived; of those, only about 200 remain today.

It has been estimated that of the 265.000 Jews living in Lithuania in June 1941, 254.000 or 95% were murdered during the German occupation. No other Jewish community in Nazi-occupied Europe was so comprehensively destroyed.

The Red Army occupied Lithuania in June 1940, and the country remained under Soviet control until June 1941, when it fell to the invading German Army (Wehrmacht). On 8 July 1941 an order was issued stating that all Jews had to wear a special patch on their back; subsequently they were ordered to wear the patch on their chest. In addition Jews were forbidden to walk along the main streets of the city, and shops were ordered to sell them food in limited amounts. Jewish people were fired from their jobs, deprived of the means of personal transportation and radios, forbidden to use public transport, and prohibited from public places. Jews were arrested on the streets, at their work places, and in their houses.

The Kaunas (Kovno) Ghetto

Between 1920 and 1940, Kaunas (Kovno) was Lithuania's capital and largest city. It had a Jewish population of 35.000-40.000, about one-fourth of the city's total population. Jews were concentrated in the city's commercial, artisan, and professional sectors.

Kaunas was also a centre of Jewish learning. The yeshiva in Slobodka, an impoverished district of the city, was one of Europe's most prestigious institutions of higher Jewish learning, with a rich and varied Jewish culture. The city had almost 100 Jewish organizations, 40 synagogues, many Yiddish schools, 4 Hebrew high schools, a Jewish hospital, and scores of Jewish-owned businesses. It was also an important Zionist center.

Kaunas‘ Jewish life was disrupted when the Soviet Union occupied Lithuania in June 1940. The occupation was accompanied by arrests, confiscations, and the elimination of all free institutions. Jewish communal organizations disappeared almost overnight. Soviet authorities confiscated the property of many Jews. Meanwhile, the Lithuanian Activist Front, founded by Lithuanian nationalist emigres in Berlin, clandestinely disseminated antisemitic literature in Lithuania. Among other themes, the literature blamed Jews for the Soviet occupation. Hundreds of Jews were exiled to Siberia.

Following Germany's invasion of the Soviet Union on 22 June 1941, Soviet forces fled Kaunas. Immediately before and following the German occupation of the city on June 24, anti-Communist, pro-German Lithuanian mobs began to attack Jews (whom they unfairly blamed for Soviet repression), especially along Jurbarko and Krisciukaicio streets. These right-wing vigilantes murdered hundreds of Jews and took dozens more Jews to the Lietukis Garage, in the city center, and killed them there.

Moving into the Kovno ghetto.

George Kadish, photographer, George Kadish, Florida.

Entrance gate to the Kaunas (Kovno) Ghetto (1941-1944).

Etching dated 1943, by Esther Lurie.

Street corner in the Kaunas Ghetto.

In early July 1941, German Einsatzgruppe (mobile killing unit) detachments and their Lithuanian auxiliaries began systematic massacres of Jews in several of the forts around Kaunas. These forts had been constructed by the Russian tsars in the nineteenth century for the defense of the city. Einsatzgruppe detachments and Lithuanian auxiliaries shot thousands of Jewish men, women, and children, primarily in the Ninth Fort, but also in the Fourth and Seventh forts. Within six months of the German occupation of the city, the Germans and their Lithuanian collaborators had murdered half of all Jews in Kaunas.

Ghetto street, November 1943.

Footbridge connecting the large and the small ghetto.

The Nazis established a civilian administration under SA Major General Hans Kramer. Between July and 15 August 1941, the Germans concentrated the remaining Jews, some 29.000 people, in a ghetto established in Slobodka. It was an area of small primitive houses and no running water. The ghetto had two parts, called the "small" and "large" ghetto, separated by Paneriu Street. In the autumn of 1943, the SS assumed control of the ghetto and converted it into the Kauen concentration camp. On 8 July 1944, the Germans evacuated the camp, deporting most of the remaining Jews to the Dachau concentration camp in Germany or to the Stutthof camp, near Danzig, on the Baltic coast. Three weeks before the Soviet army arrived in Kaunas, the German razed the ghetto to the ground with grenades and dynamite. As many as 2.000 people burned to death or were shot while trying to escape.

At its peak, the Ghetto held 40,000 people, most of whom were later sent to concentration and extermination camps, or were shot at the Ninth Fort. About 500 Jews escaped from work details and directly from the Ghetto, and joined Soviet partisan forces in the distant forests of southeast Lithuania and Belarus.

Youth in line for distribution of soup in the workers' kitchen in the Kaunas Ghetto.

The ghetto fire brigade with their chief Abramovitz (in front), August 1943.

Organization

The ghetto had two parts, called the "small" and "large" ghetto, separated by Paneriai Street and connected by a small wooden bridge over the street. Each ghetto was enclosed by barbed wire and closely guarded. Both were overcrowded, with each person allocated less than ten square feet of living space. The Germans continually reduced the ghetto's size, forcing Jews to relocate several times. The Germans and Lithuanians destroyed the small ghetto on October 4, 1941, and killed almost all of its inhabitants at the Ninth Fort. Later that same month, on 29 October 1941, the Germans staged what became known as the "Great Action." In a single day, they shot around 10,000 Jews at the Ninth Fort (see below).

The ghetto in Kovno provided forced labor for the German military. Jews were employed primarily as forced laborers at various sites outside the ghetto, especially in the construction of a military airbase in Aleksotas. The Jewish council (Aeltestenrat; Council of Elders), headed by Dr. Elkhanan Elkes, also created workshops inside the ghetto for those women, children, and elderly who could not participate in the labor brigades. Eventually, these workshops employed almost 6,500 people. The council hoped the Germans would not kill Jews who were producing for the army.

Jewish workers on their way back to the Ghetto after a day of forced labour.

|

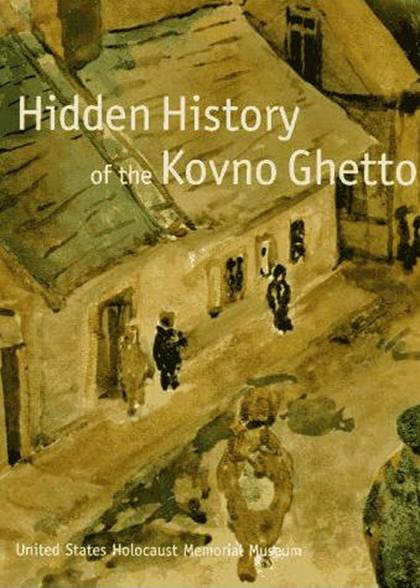

The Underground School As an act of defiance an underground school was conducted in the Kovno Ghetto when such education was banned in 1942. A remarkable photo of one of the classes of that school features in the US Holocaust publication, "The Hidden History of the Kovno Ghetto". Identification of the teacher visible in that photo is given in a website that deals with the hidden school. However almost all of the children in the Ghetto, approximately 2,500, were removed in the Kinder Aktion of 27–28 March 1944. |

|

Unidentified child in the Kaunas Ghetto, 1943.

www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/jsource/Holocaust/finkelsteinkovno.html

Smuggling Babies out of the Ghetto

From 1942 births were not permitted in the ghetto and pregnant women faced death. However a number of babies of ages from about 9 months to 15 months were smuggled out of the Kovno Ghetto to willing Lithuanian foster mothers.

Final days

In the autumn of 1943, the SS assumed control of the ghetto and converted it into the Kovno concentration camp. The Jewish council's role was drastically curtailed. The Nazis dispersed more than 3,500 Jews to subcamps where strict discipline governed all aspects of daily life. On October 26, 1943, the SS deported more than 2,700 people from the main camp. The SS sent those deemed fit to work to Vaivara concentration camp in Estonia, and deported surviving children and the elderly to Auschwitz.

On 8 July 1944, the Germans evacuated the camp, deporting most of the remaining Jews to the Dachau concentration camp in Germany or to the Stutthof camp, near Danzig, on the Baltic coast. Three weeks before the Soviet army arrived in Kovno, the Germans razed the ghetto to the ground with grenades and dynamite. As many as 2,000 people burned to death or were shot while trying to escape the burning ghetto. The Red Army occupied Kaunas on 1 August 1944. Of Kaunas‘ few Jewish survivors, 500 had survived in forests or in a single bunker which had escaped detection during the final liquidation; the Germans evacuated an additional 2,500 to concentration camps in Germany.

Jewish women standby murdered corpses outside

the Seventh Fort in Kaunas.

Resistance

Throughout the years of hardship and horror, the Jewish community in Kaunas documented its story in secret archives, diaries, drawings and photographs. Many of these artifacts lay buried in the ground when the ghetto was destroyed. Discovered after the war, these few written remnants of a once thriving community provide evidence of the Jewish community's defiance, oppression, resistance, and death. George Kadish (Hirsh Kadushin), for example, secretly photographed the trials of daily life within the ghetto with a hidden camera through the buttonhole of his overcoat.

Monument of the Kaunas Ghetto

The Kovno ghetto had several Jewish resistance groups. The resistance acquired arms, developed secret training areas in the ghetto, and established contact with Soviet partisans in the forests around Kaunas.

In 1943, the General Jewish Fighting Organization (Yidishe Algemeyne Kamfs Organizatsye) was established, uniting the major resistance groups in the ghetto. Under this organization's direction, some 300 ghetto fighters escaped from the Kovno ghetto to join Jewish partisan groups. About 70 died in action.

The Jewish council in Kaunas actively supported the ghetto underground. Moreover, a number of the ghetto's Jewish police participated in resistance activities. The Germans executed 34 members of the Jewish police for refusing to reveal specially constructed hiding places used by Jews in the ghetto.

The completely destroyed Kaunas Ghetto. In July 1944, the Germans blew up and

burned down the ghetto in search of Jews in hiding there.

Read more…

http://www.ushmm.org/museum/exhibit/online/kovno/intro/intro.htm

http://www.ushmm.org/wlc/en/article.php?ModuleId=10005174

http://www.holocaustresearchproject.org/ghettos/kovno.html

http://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/jsource/Holocaust/kovnotoc.html

http://www.fold3.com/page/286123943_the_kovno_ghetto_partisans_chaim_yelin/

http://www.lithuanianjews.org.il/HTMLs/article_list4.aspx?C2014=14287&BSP=14432&BSS59=14432

http://www.aish.com/ho/p/48949791.html

Books:

http://jewishhistoryaustralia.net/TheHistoryOfNow/Kovno/resource.php

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - (3) Comment

Kaunas massacre of 29 October 1941

The largest mass murder

of Lithuanian Jews

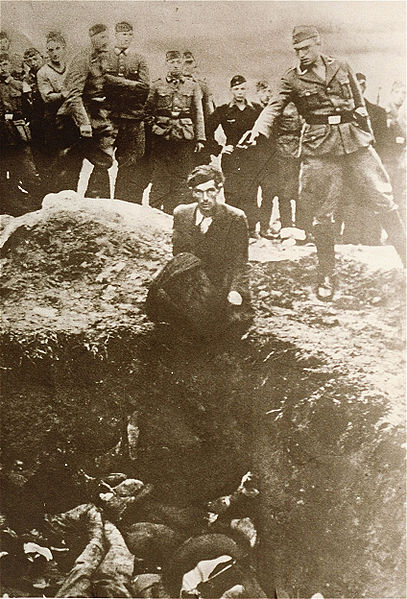

Thousands of Jews were killed to fall in pits like these.

Kaunas massacre of 29 October 1941, also known as the Great Action, was the largest mass murder of Lithuanian Jews.

By the order of SS-Standartenführer Karl Jäger and SS-Rottenführer Helmut Rauca, the Sonderkommando under the leadership of SS-Obersturmführer Joachim Hamann, and 8 to 10 men from Einsatzkommando 3, in collaboration with Lithuanian henchmen, murdered 2,007 Jewish men, 2,920 women, and 4,273 children in a single day at the Ninth Fort, Kaunas, Lithuania.

With the arrival of the SS Einsatzgruppen, the 'Great Action' began on October 28th. The Jewish inhabitants of the Ghetto were assembled on Democrats Square and all those fit for work were allowed back into the Ghetto. The others, over 9,000 men, women and children were marched to the SS execution centre in the Ninth Fort and there, stripped of their clothes and in the freezing cold, they awaited their fate. In groups of 200, they were stood on the edge of large pits, dug previously by Russian P.O.W.s, and were systematically machine-gunned to death.

These mass graves were later re-opened and all the bodies burned in an attempt to conceal the crime. This work was done by 72 men and women from the ghetto. While working, the prisoners were chained together to prevent escapes but all were later put to death when their work was finished.

In July, 1944, the Ghetto was burned down, blown apart and completely destroyed. The Germans and Lithuanians destroyed the small ghetto on October 4, 1941, and killed almost all of its inhabitants at the Ninth Fort. Later that same month, on October 28, SS-Rottenführer Helmut Rauca of the Kaunas Gestapo (secret state police) conducted the selection in the Kaunas Ghetto. All ghetto inhabitants were forced to assemble in a central square of the ghetto. Rauca selected 9,200 Jewish men, women, and children, about one-third of the ghetto population. The next day, 29 October, they shot these people at the Ninth Fort in huge pits dug in advance.

Jewish women, minutes before they are murdered by the

SS and their Lithuanian henchmen, Kaunas 1941.

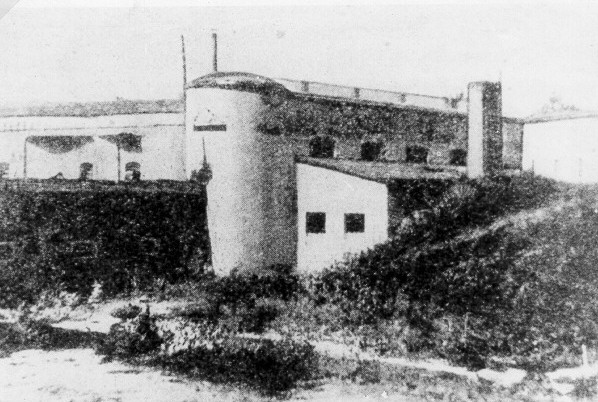

KAUNAS’ NINTH FORT

At the end of 19th century, the city of Kaunas was fortified, and by 1890 it was encircled by eight forts and nine gun batteries. The construction of the Ninth Fort (its numerical designation having stuck as a proper noun) began in 1902 and was completed on the eve of World War I. From 1924 on, the Ninth Fort was used as the Kaunas City prison.

During the years of Soviet occupation, 1940-1941, the Ninth Fort was used by the NKVD to house political prisoners on their way to the labour camps in Siberia.

During the years of Nazi occupation, the Ninth Fort was put to use as a place of mass murder. At least 10,000 Jews, most of Kaunas, largely taken from the Kovno Ghetto, were transported to the Ninth Fort and killed by Nazis with the collaboration of some Lithuanians in what became known as the Kaunas massacre.

Notable among the victims was Rabbi Elchonon Wasserman of Baranovitch. In addition, Jews from as far as France, Austria and Germany were brought to Kaunas during the course of Nazi occupation and executed in the Ninth Fort. On 1943 the Germans operated special Jewish squads to open the massgraves and burn the remaining corpses. Such squad of 62 people managed to escape the fortress on the eve of 1944. In 1944, as the Soviets moved in, the Germans liquidated the ghetto and what had by then come to be known as the "Fort of Death", and the prisoners were dispersed to other camps. After World War II, the Soviets again used the Ninth Fort as a prison for several years. From 1948 to 1958, farm organizations were run out of the Ninth Fort.

In 1958, a museum was established in the Ninth Fort. In 1959, a first exposition was prepared in four cells telling about Nazi war crimes carried out in Lithuania. In 1960, the discovery, cataloguing, and forensic investigation of local mass murder sites began in an effort to gain knowledge regarding the scope of these crimes.

Through this door, 64 prisoners escaped on 25 December 1943.

TODAY A MUSEUM

The Ninth Fort museum contains collections of historical artifacts related both to Soviet atrocities and the Nazi genocide, as well as materials related to the earlier history of Kaunas and Ninth Fort.

The memorial to the victims of Nazism at the Ninth Fort in Kaunas, Lithuania, was designed by sculptor A. Ambraziunas. Erected in 1984, the monument is 105 feet (32 m) high. The mass burial place of the victims of the massacres carried out in the fort is a grass field, marked by a simple yet frankly worded memorial written in several languages. It reads, "This is the place where Nazis and their assistants killed more than 30,000 Jews from Lithuania and other European countries."

On April 11, 2011, the memorial to the victims of Nazism was vandalized - The memorial tombstones were knocked down, and white swastikas were sprayed on the memorial. On the adjacent sidewalk, the words “Juden raus” (German: Jews Out) were inscribed.

Kaunas – A sign saying “Jews out” and “Hitler was right” (Juden raus“„Hitleris buvo teisus“)

were hung in front of the synagogue on April 20th 2011, Hitler's day of birth.

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - (7) Comment

How I escaped from

How I escaped from

the Kaunas Ghetto

My coffee chat with Irena Veisaite (84) started here in the kitchen of her cosy apartment in the outskirts of

Vilnius Old Town. What a life story hasn’t this gentle lady got to tell...

Text/photos: Aage Myhre

A room full of books. A desk covered with pamphlets, documents, newspaper clippings. Walls and bookshelves overcrowded with framed photographs of friends and relatives. Her today’s home in Vilnius is filled with warmth and wisdom. Was this the way they lived? The Lithuanian Jews, often named as the Litvaks. Before the World War II horrific events so brutally took them and their culture here in Lithuania away forever? Or perhaps not forever? Because here she lives, Irena Veisaite, born in this country in 1928. She is one of the few Litvaks who survived the Holocaust in Lithuania. A living evidence of cruelty and injustice. Yet with less bitterness and anger than you might think.

"Love," she says, "love is so much more important than hatred. Hatred is the most destructive feature that humanity possesses and even in the most difficult times I experienced a lot of kindness".

Irena was born in 1928 in Kaunas, the inter-war Lithuanian capital when Vilnius and the south-western part of the country was occupied by Poland. Her parents had a liberal European education and she grew up, as she describes, surrounded by very different people. She was playing with the neighbourhood children and never thought much of what nationality the other kids were. It was only when rumours of a potential war grew in strength that she began to feel a certain degree of insecurity.

"But," she says," my biggest fear in the early 1930's was that my parents would divorce. Not the potential war."

She also remembers with great pleasure that the house her father built in Kaunas in 1936 was named as Lithuania's top residential housing. However, insecurity began to make itself increasingly evident in the late thirties. More and more often her parents whispered among themselves. About Adolph Hitler. About growing fears of war. Eight-year-old Irena began to experience painful nightmares. She would often wake up at night because of frightening dreams of a deadly despot, a man who was now leading a country that she and her family had so many good memories about, a country named Germany.

"I learned a new phrase when I was eight years old," she tells me while we sit in her book-crowded apartment in Vilnius this early February day. "The word was 'Anti Semitism'. “But what this word really meant I understood only much later.”

Irena stands in her kitchen, making coffee for me while she talks about those first, painful childhood experiences.

"Unfortunately my greatest childhood fears came true when I was 10 years old and my parents decided to divorce. The agreement was that I should stay with my mother in Kaunas during the year but spend the summer vacations with my father. In the summer of 1938 my father took me on a wonderful European trip. We travelled through Berlin to Switzerland, Belgium and France”

"It is very vivid in my memory how we walked along Berlin's famous street, Unter den Linden, and saw the yellow benches which were different from all others, meant only for the Jews. As foreigners, we could have sat down on any bench, but my father insisted that we should sit on a yellow bench out of solidarity with the German Jews and to get the feeling of what it meant to be excluded."

|

In German city parks by the end of the 1930s, there were yellow benches bearing the logo “for Jews only.” Jews were not permitted to sit on any other park benches nor use public transportation or drive a car. These measures made it easy to identify the stigmatized Jews so that they could then be transported to ghettos in the East and finally carted to their deaths in concentration camps such as Sobibor, Auschwitz, Neuengamme, Buchenwald etc. |

|

In 1939, Hitler's war machinery started to roll east. The infamous Molotov-Ribbentrop pact was signed that year, and it soon became clear that little Lithuania was about to be squeezed between two superpowers that were not to show any mercy to the Lithuanian people.

The Soviet Union's first WWII occupation of Lithuania took place in 1940. One year later they were driven back by the German troops and the country was suddenly under German domination. While the Soviet occupation was infinitely tragic for the ethnic Lithuanians, due to the memory of the Tsarist Russia's occupation of the country from late 1700's until well into the First World War and especially the deportations of the 14 June 1941, the Nazi occupation may have appeared as liberation from the Soviet dictatorship.

For the Jews deportation to Siberia was still a chance to survive, while the devastating Nazi occupation meant certain death. Jews and Lithuanians, who had lived in peace and harmony side by side for hundreds of years, became involuntary victims of a war none of them wanted.

Irena recalls the outbreak of the war as a very dark time. She remembers the overpowering Nazi propaganda which identified all the Jews with Communists who betrayed their homeland - Lithuania - to the Soviet Union. The Jews were apportioned the blame for carrying out the deportations of the Lithuanians to Siberia without any mention of the fact that many Jews were also deported. The mood of hatred and retaliation escalated, there were pogroms in Kaunas. Jewish people were arrested and shot in the streets.

Just a few days after the German occupation in June of 1941, Irena's mother was arrested in hospital where she was recovering after major kidney surgery. She was taken to a prison and it is estimated that she was executed in mid-July. 13-year old Irena became motherless in an unimaginably tragic way.

Irena's voice trembles when she talks about her Mother and what happened that July day.

After the brutal murder, Irena remained alone because her father then lived in Belgium (where he survived the war). They had no contact anymore.

During the war years that followed, there was substantial cooperation and collaboration between the German forces and some Lithuanians. The Lithuanian Activist Front volunteer police force, known as Tautinio Darbo Apsaugos Batalionas (TDA), that was hoping to be transformed into a regular army of independent Lithuania, became instead employed by the Germans as auxiliary in massacres of the Jews during the Holocaust that led to the tragic destruction of around 200 000 Jews, about 90- 95% of the country’s pre-war Jewish population.

In August 1941 all the Kaunas Jews were imprisoned in the ghetto which was located in the Kaunas suburb Vilijampole. Irena stayed in the ghetto with her grandparents and one aunt.

The 7th of November 1943 is a date Irena will never forget. Lithuanian friends of her parents, the Strimaitis family, had managed to convey a message to her in the ghetto, saying that she should follow one of the labour brigades out of the ghetto to the work place in town. They also had procured false documents for her. An agreement was reached with a Jewish policeman who was responsible for the list of workers that she should not be included on the list that day, but still follow the group out and then try to escape unnoticed into a side street as soon as they passed the ghetto gates. The moment of stepping out of the column of Jewish workers was the most horrifying and dangerous one in young Irena's life. But fortunately she made it without being detected.

Kaunas Ghetto street, November 1943.

She managed to get off the yellow stars that all Jews were obliged to bear on both the chest and back, and went unnoticed to the agreed meeting point on the Viljampole bridge across river Neris. The work brigade had been more than an hour late out of the ghetto that day, and her family friends had already gone home when Irena came to the meeting place, so she had to find her way alone, walking through the centre of town.

Irena knew the address to the Strimaitis family and managed to find their house in the centre of Kaunas. What she did not know was the number of their apartment, so she found herself ringing the caretaker's door bell. Both she and her friends knew, however, that caretakers were among the most eager informers for the Gestapo, and her contact with the caretaker made the friends so nervous that none of them could sleep that night.

Early next morning they travelled to Vilnius, hoping that the caretaker had not been able or wanted to alert the Gestapo. Irena's Lithuanian was luckily very good, so it was also possible that the caretaker had not realized that she was Jewish.

The Strimaitis family continued to take care of Irena and found a few places for her to stay in Vilnius. Finally, in March 1944, she was taken into a home of Stefanija Ladigiene who took her into her family and became her ‘second mother’. She stayed with this family also after the war had ended because she had no one else left. All her friends and family had perished in the Holocaust.

As Irena had identification papers (false, though) she was able to take a job. Marcele Kubiliute, a friend of the Strimaitis family, found her a job at an orphanage in Vilnius Old Town, where she worked in the laundry and as a cleaner until the summer of 1944.

When the Soviets re-occupied Lithuania the summer of 1944, Irena desperately wanted to rebuild her life. She entered a Lithuanian high school in Vilnius which she finished in record speed, taking only three years instead of the usual five, to get her final exam papers. She then applied to Vilnius University to study Lithuanian Language and Literature. Unfortunately at this time the KGB was after Irena and wanted to enlist her as an informant, to which she would never agree. Her ‘second mother’ was arrested in March 1946, and there was another complication: Irena's father lived abroad and was classified as a bourgeois, and for this reason she was in danger of being expelled from the University. With the help of her relatives in Moscow she left Vilnius and continued her education in Moscow, studying German language and literature.

In 1953, having graduated from the Moscow Lomonosov State University, Irena came back to Vilnius, determined to work in Lithuania. She became a lecturer at the Pedagogical University in Vilnius, where she taught the history of Western European and German literature. She later taught at other universities, and became involved in theatre and many other activities, although the pedagogical university remained her main employer, through 43 relatively good, happy years.

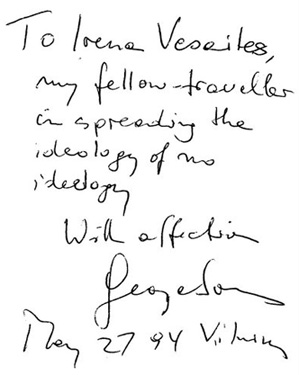

Soon after Lithuania's new process of liberation, in 1990, Irena, together with Professor Ceslovas Kudaba was invited by the philanthropist and billionaire George Soros to create the Open Society Fund in Lithuania.

"I was happy to accept the offer. I felt like I was getting new wings because this gave me the possibility to do on a much bigger scale what I was trying to do all my life - stimulating critical and creative thinking and bringing Lithuania back to Europe and basic European human values... To show an alternative to Soviet thinking. I accepted his invitation to lead the Fund for the years 1990-2000."

Today Irena is still working with George Soros and his Open Society Fund, and now acts as Ombudsman for his worldwide organization.

|

|

To Irena Veisaite, With affection

|

In spite of her tragic past Irena leads a very active life. She is appreciated for her positive thinking and tolerance, and was in 2002 awarded the prestigious title; "Person of Tolerance in Lithuania.” Irena is not affected by hatred or revenge.

As she puts it to me; “I do not remember the faces of any evil people from my past, but I do very well remember the faces of those that expressed goodness. We have to learn to love and to understand..."

Dr. Irena Veisaite (84) at her study desk in Vilnius, Lithuania.

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

VilNews e-magazine is published in Vilnius, Lithuania. Editor-in-Chief: Mr. Aage Myhre. Inquires to the editors: editor@VilNews.com.

Code of Ethics: See Section 2 – about VilNews. VilNews is not responsible for content on external links/web pages.

HOW TO ADVERTISE IN VILNEWS.

All content is copyrighted © 2011. UAB ‘VilNews’.

Click on the buttons to open and read each of VilNews' 18 sub-sections

Click on the buttons to open and read each of VilNews' 18 sub-sections

.jpg)