THE VOICE OF INTERNATIONAL LITHUANIA

|

VilNews has its own Google archive! Type a word in the above search box to find any article.

You can also follow us on Facebook. We have two different pages. Click to open and join.

|

Litvak forum

- Posted by - (11) Comment

|

IN MEMORY OF JEWISH KAUNAS |

Chiune Sugihara:

The Japanese diplomat/

spy who became a hero of the Holocaust

By Boris Bakunas, PhD

In the Year of Shame 1940, while the bulk of the German military machine was consolidating its grip on Poland, 110 French and British divisions sat idly on the Western Front, facing a token German force a fraction its size.

In the Year of Shame 1940, the People’s Commissariat for Internal Affairs, the dreaded NKVD, massacred 22,000 captured members of the Polish Officer Corps, turning the Katyn Forest into a vast mass grave.

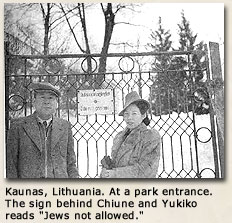

In that same Year of Shame 1940, Chiune Sugihara, a Japanese diplomat and spy stationed in Kaunas, Lithuania – along with his wife Yukiko – made a joint decision in defiance of direct orders from their government, and together they lit a beacon of hope for thousands of Polish and Lithuanian Jews. From 19 July to 28 August, 1940, the two-storey, white stucco building on 30 Vaizgantas Street that housed the Japanese Consulate, became the moral capital of the world.

Chiune and Yukiko Sugihara with their two children had arrived in Kaunas from Helsinki in 1939 not long after Nazi and Soviet troops sliced Poland into two zones of terror. Chiune’s ostensible mission was to serve as the Japanese Vice-Consul in Kaunas. His real assignment was to gather intelligence on the strength of the Soviet military in the West.

But a chance encounter at a delicatessen with an eleven-year-old Lithuanian-Jewish boy named Solly Ganor intervened, transforming the suave foreign-service officer renowned in diplomatic circles for throwing lavish parties into a hero of the Holocaust.

Jewish

refugees at the gate of the Japanese Consulate in Kaunas, July 1940.

Thousands

of Jews lined up here, hoping to receive transit visas allowing

them

to escape to the Far East and to America or Palestine.

“Now is the time to leave.”

Years later, an elderly, but healthy Solly Ganor recalled that fateful encounter.

As Solly, his hair flaked with snow, stepped through the door of his Aunt Anushka’s delicatessen in Kaunas, he saw her chatting amiably with “an elegantly-dressed man with strange, slanting eyes.”

“Ah, my dear nephew has come for his Hanukah money,” Aunt Anushka exclaimed. “Come here and meet his Excellency, the Consul of Japan, Mr. Sugihara.”

“How do you do, Sir?” Solly said.

The man shook Solly’s hand and smiled. Solly remembers taking an immediate liking to him. “There was humor and kindness in those strange eyes,” he later recalled.

Aunt Aunushka said to Solly, “You want to go to the movies, and you need a litas, right?” Solly nodded eagerly.

But before Aunt Anushka could get to the cash register, Mr. Sugihara reached into his pocket and handed Solly a shiny coin. “Since this is Hanukah, consider me your uncle.”

Solly hesitated. Then he impulsively blurted out an invitation. “Since you are my uncle, then you should come Saturday to our Hanukah party. The whole family will be there.”

The arrangements made, Solly went off to see a Laurel and Hardy film.

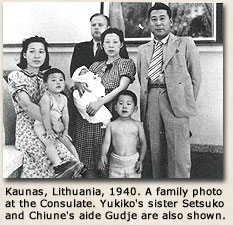

At six, Aunt Anushka arrived with Mr. and Mrs.Sugihara and Yukiko’s sister Setsuko at the Ganors’ apartment. Solly recalled that Mr. Sugihara wore a striped suit. His wife Yukiko, was dressed in an elegant black dress.

The Ganors had lived in Kaunas for generations. Solly’s father Chaim was a successful businessman. Among the many guests were two refugees from Warsaw, Mr. Rosenblatt and his little daughter, Lea.

The family and guests sat down at the long dinner table. Yukiko had never seen such a huge meal. There was even a duck, Japanese-style, which Aunt Anushka had specially prepared.

Mr. and Mrs.Sugihara attentively watched the Hanukkah rituals. Solly noticed that Mr. Sugihara was particularly interested in the story of Judah Maccabee, the leader of a successful Jewish revolt against foreign invaders in the second century B.C.E. He asked many questions about it.

Later, Mr. Sugihara asked Solly about his hobbies. When he learned that stamp collecting was one of them, he invited Solly to the consulate to see some Japanese stamps.

After dinner, Mr. Rosenblatt described his narrow escape from Poland and the things he had witnessed: his wife’s death during the bombings of Warsaw, Jews terrorized by Nazis and anti-Semites, arrested, and shipped off to camps. As he recounted the atrocities, Mr. Rosenblatt started to cry.

“It was painful to hear those horrible stories,” Solly recalled. “But Sugihara listened to every word.”

Later Solly overheard Mr. Rosenblatt pleading with Mr. Sugihara to issue him a visa so he could leave Kaunas. “Even a transit visa will help.”

Mr. Sugihara told Mr. Rosenblatt to come see him.

One day after school, Solly visited the consulate. Mr. Sugihara showed him into his office and pulled out an envelope from his desk drawer containing Japanese stamps. After showing him the stamps, Mr. Sugihara asked Solly a series of questions.

Had Mr. Rosenblatt and his daughter gotten their transit visas yet? How was Solly’s family faring? Solly knew that his father was hesitant about selling the family business. He couldn’t imagine Hitler invading Lithuania with Soviet troops in the country.

Mr. Sugihara’s voice suddenly sounded serious. Would Solly give his father an important message? Solly nodded. Mr. Sugihara spoke very quietly, as if he were telling a secret. “The time to leave is now,” he said.

|

|

|

|

“They all looked so sad.”

On the morning of July 27, 1940, as was his custom, Chiune rose early, ate breakfast, and climbed down the stairs to consular office below. What he saw outside his window caused him to rush back upstairs to show Yukiko.

Instead of the tranquil tree-lined street, she saw a crowd of about two hundred people, many of them dressed in bedraggled clothes.

“There were children, women, and young men,” Yukiko later said. “They were all hanging onto the fence. The young men were trying to climb over the fence. But the security of the consulate was pushing them back.”

Yukiko took several photographs. “They all looked so sad. Some women were looking right at me with great sorrow.”

To calm the throng, Chiune Sugihara agreed to meet with a delegation of five in his office. Zorach Warhaftig, a leader of Poland’s religious Zionists, was selected as head of the group. One by one the delegates described the terrible plight of the Jews. Mr. Warhaftig also told Mr. Sugihara that the Dutch consul had agreed to give Jewish refugees entrance visas for the Dutch Caribbean island of Curacao. But to get there, they would have to travel to Japan first. Would Mr. Sugihara issue transit visas for Japan?

Mr. Sugihara expressed his deep sympathy. However, he could issue only a few visas on his own authority. He told the Jewish delegates that he needed time to think. He asked them to come back the next day.

That night Chiune and Yukiko tossed and turned in a restless half-sleep. In the morning, they saw that the crowd had grown. Entire families were now sleeping on the ground, afraid that they might lose their place in line.

When Sugihara met with the Jewish delegates, the acting Dutch consul, Mr. Jan Zwartendijk, was also present.

Mr. Zwartendijk affirmed that he was willing to do all he could to help. Everybody now looked at Mr. Sugihara. Looking them straight in the eyes, Mr. Sugihara announced that he was willing to cable the Japanese Foreign Ministry for permission to grant transit visas, provided that his wife agreed.

The meeting adjourned. The first spark of hope had been struck. What had begun as a chance meeting between an eleven-year-old boy and a Japanese Consul was fast turning into a conspiracy.

Chiune

Sugihara with his wife Yukiko

“This request is a humanitarian plea.”

That evening Chiune and Yukiko descended the stairs to the consular office, where Chiune began the laborious process of encoding a cable to the Foreign Ministry. Yukiko transcribed the cable in triplicate by hand.

“I request permission to issue visas to hundreds of Jewish people who have come to the consulate here in Kaunas seeking transit visas. They are suffering terribly. As a fellow human being, I cannot refuse their requests. Please permit me to issue visas to them. This request is a humanitarian plea. The refugees’ request for visas should not be denied.”

Two days later, Chiune Sugihara decoded a cable from Japan. His urgent plea had been emphatically denied. The denial ended with the words. “No exceptions. STOP. No further inquiries expected. STOP. K. Tanaka, Foreign Ministry Tokyo.”

Undaunted, Sugihara sent a second request. The crowd of refugees, many with faces ashen from hunger and fatigue, continued to grow.

A second cable from Tokyo arrived. “Permission denied.”

Sugihara tried a third and final time. DENIED!

Wearily he went upstairs to share the bad news with Yukiko. They both knew they faced a grim, and possibly deadly choice.

If Chiune defied the Foreign Ministry’s orders, at the very least, his career would be ruined. At worst, he would be placing his life and the lives of his wife and children in peril. As Yukiko later said, “If we were in Germany, and we did something like that, my husband, myself, my children could all be taken away by the Nazis. I didn’t know what they would do to us. Maybe they’d kill us.”

Chiune looked into Yukiko’s eyes and told her that he had decided to issue visas under his own authority. Did she approve? Yes.

The next day, Chiune Sugihara had his chauffer drive him to the Soviet Embassy where he met with the Soviet consul. Sugihara spoke fluent Russian. After a brief period of negotiation, the Soviet consul agreed to allow the refugees to travel across the Soviet Union via to trans-Siberian railroad to ports along the Pacific coast where they could board ships for Japan, but at five times the standard price.

As the shiny black Buick with the Japanese flag slowly drove past the refugees outside the consulate, all eyes were trying to gauge the look on the diplomat’s face. But they saw no hint of what had transpired. The tension in the crowd grew.

Finally, Mr. Suhigara stepped out of the building and stood in front of the gate. In a calm, authoritative voice, he announced that he would issue a visa to every man, woman, and child. After a moment of stunned silence, the crowd erupted in cries of joy. Families and friends hugged and kissed.

Sugihara interviewed each refugee, asking probing questions in an attempt to find useful details to write on the visas. Each visa had to be written by hand, signed, stamped, and registered in a log containing its number and the name of the person or family who received it.

As

word spread among the Jewish community in Kaunas, the crowd in front of the

consulate mushroomed. To speed up the process Sugihara ordered his staff,

including his German assistant Wolfgang Gudze, to assist him.

“How can I handle a thousand visas?”

Among those who came to the consulate was Moses Zupnik, a yeshiva student who

looked barely out of his teens. His purpose? To obtain 300 visas for the Mir

Yeshiva, a Jewish school for religious education.

Zupnik later recalled: “I came in, and I was all excited. And I saw that he measured me. He was sitting at his desk and he was measuring me from the top to the bottom. Who I am? What I am? I said to him, ‘I am a representative of the Mir Yeshiva, and we want to go to Curacao. We just want to go through Japan.”’

Zupnik fidgeted nervously as he awaited Sugihara’s response. To his amazement, Sugihara agreed to write all 300 visas.

“I still remember when he looked at me, when he said, ‘Alright I’ll give you all the visas.’ I don’t forget these things, because they are still all alive in me. He saw people suffering, and he thought maybe he could help. And he helped.”

When Zupnik returned a few days later to pick up the visas, he found Wolfgang Gudze fraught with panic. “How can I handle a thousand visas?”

Zupnik said, “You know what? I will help you.”

When Sugihara heard about the offer, he said to Gudze, “Let him help you.”

For the next two weeks, Zupnik and Gudze worked side by side assisting Sugihara. During that time, Gudze made a deep impression on Zupnik. “He was a zaddik, a groyse zaddik” (a righteous man), Zupnik said years later.

But others reported that Gudze was a Gestapo agent

Then on 2 August, a cable from the Japanese Foreign Ministry arrived, ordering Sugihara to shut down the consulate immediately. Since the Soviets had forcibly “annexed” Lithuania into the U.S.S.R. in late July, they did not want any consulates in Kaunas. Sugihara fired off a passionate appeal to the Soviet Embassy for a delay. He was told that his request would be placed under consideration.

Sugihara speeded up the visa writing process again. Soon he was working 16 hours a day. By evening his hands ached so fiercely that Yukiko had to massage them before he could fall asleep.

On 10 August. Sugihara saw that the ever-swelling crowd now included the poorest of the poor, late-comers who lacked the connections to hear about the goings-on in the Japanese consulate. “They all seemed very tired and exhausted,” Sugihara wrote. “I did not know whether they had any place to sleep in Kaunas, maybe they just slept in the station or on the street.”

Sugihara told his staff that from now on he would issue visas even to those whose documents were obvious forgeries, even to those with no documents at all.

In mid-August, the long-dreaded reply for an extension from the Soviets arrived. Hands trembling, Sugihara slit the envelope open. Gudze heard him sigh with relief. Inexplicably, the Soviets had agreed to an extension until 28 August.

The unexpected news reinvigorated Chiune. Yukiko offered to help write visas, but he refused, firmly ordering her to stay as far away from the consular office as possible. Perhaps he didn’t trust Gudze. Most likely, he didn’t trust anybody. What he was sure of was that the responsibility for his actions should fall on his shoulders alone.

Former

Japanese consulate in Kaunas.

“Banzai Nippon!”

Then came a final warning from Japan. Close the consulate immediately and

leave. Chiune told Yukiko to start packing, while he, Gudze, and Zupnik

continued writing visas.

On 28 August, their suitcases packed and all documents burnt, the Sugihara family squeezed into the black Buick and drove off.

By this time Chiune Sugihara was worn out.

“He was so exhausted, like a sick person.” Yukiko recalled. “Even though he was ordered to go to Berlin, he said he couldn’t make it to Berlin and suggested we go to a hotel and rest before leaving.”

On the gate, Sugihara had left a note for the refugees. It said that he would be staying at the Metropolis Hotel.

Even before he could settle into his room, Sugihara got an urgent message from the hotel desk. He was needed downstairs. Having read the note on the gate, the refugees had followed him to the hotel. Sugihara wrote more visas. He wrote and he wrote until the family finally had to leave for the station and board the train for Berlin.

The refugees followed.

On the train, Sugihara continued to write visas on plain paper, signing them and flinging them indiscriminately to outstretched hands in the hope that the refugees would fill them in and find a way to outwit the Soviet and Japanese officials on their own.

As the train moved away from the station, Sugihara heard a voice shout, “Banzai Nippon!” Others joined the chorus. “Banzai Nippon! Banzai Nippon!’ These words meant “Long live Japan!” Sugihara had told some of the refugees to say this when they encountered Japanese officials.

Some witnesses reported they heard Sugihara say, “Please forgive me. I cannot write anymore. I wish you the best.”

Chiune

Sugihara memorial in Vilnius.

“I

may have disobeyed my government, but if I didn't I would be disobeying God."

Chaim Ganor never sold his business. He and dozens of other family

members, including Aunt Anushka, were sent to German concentration camps. Only

Chaim, Solly, and Solly’s sister survived.

On May 2, 1945, Solly Ganor lay nearly

frozen under a blanket of snow. A four-man signal unit of the US 522th

artillery battalion was passing by, when one of the soldiers looked back and

said, “Hold it fellow, something strange is lying there in the snow.”

They found a whole group of people in striped clothing. The soldier picked

Solly up. Solly looked into his eyes and saw that they looked strangely

familiar – slanted. The soldier was Corporal Clarence Matsomura. Years later

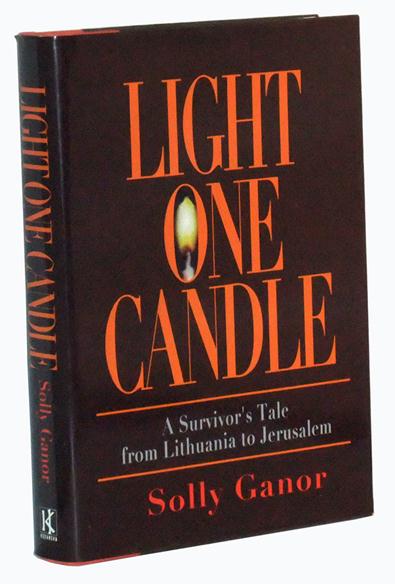

Solly and Clarence met again in Jerusalem. In 2003, Solly Ganor’s book Light

One Candle: A Survivor’s Tale from Lithuania to Jerusalem was published.

Moses Zupnik, who came to ask Sugihara for 300 visas for the students of the Mir Yeshiva and stayed to help write visas during the two final weeks at the consulate, made it to Japan. The Japanese sent him and the other students to Shanghai, where they stayed until the war ended. Moses went to America and settled in New York City, where he became a rabbi.

Wolfgang Gudze is said to have reluctantly joined the German army. Once, when Moses Zupnik asked Gudze how he could thank him, Gudze replied. “You don’t have to thank me. But the world is a wheel. Today Hitler is on top. Tomorrow he may be down. Don’t forget what I did.” Zupnik never heard from Gudze again.

Although Mr. Rosenblatt and his little daughter Lea obtained their visas, I have not been able to learn if they survived the Holocaust.

Soon after arriving in Berlin, Chiune Sugihara was posted to Prague, where he and his family got a much-needed rest. Even so, he continued writing visas in Prague, and later in Koenigsburg, his last diplomatic post.

After the war, he and his family were detained by the Russians in one internment camp after another. The Soviet Union had declared war on Japan in August of 1945. When he returned to Japan, Chiune Sugihara was summarily dismissed from the Foreign Service in 1947. His youngest son Haruki died shortly after, but four years later a new son was born. To support his family, he worked at odd jobs, including selling light bulbs.

In 1960, because of his fluent command of the Russian language, Sugihara got a job for a trading company that did business with the Soviet Union that required him to live in Moscow. He visited his family from time to time for sixteen years until his retirement.

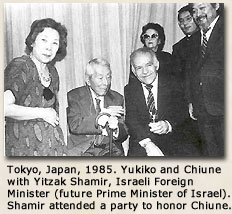

In 1968, Jehoshua Nishtri, an Israeli diplomat in Tokyo and one of the Jews Sugihara had helped save, finally tracked Sugihara down. Together with others, he lobbied the Israeli government for Chiune Sugihara’s inclusion in the Yad Vashem memorial, which was granted after extensive research, in 1985. By this time, Chiune was ill. Yukiko went to Israel and accepted the honor on his behalf. In gratitude for his deeds, Chiune Sugihara and his descendants were granted Israeli citizenship in perpetuity.

Nobody knows exactly how many visas Chiune Sugihara issued to Jewish refugees. He reported to the Japanese Foreign Ministry that he had issued 2,132 visas of which 1,500 were to Jews. It is estimated that he helped save anywhere from 6,000 to 10,000 Jews. At least 40,000 descendants of Sugihara visa-holders are alive today.

In Japan, Chiune Sugihara was honored in the year 2000 on the 100th anniversary of his birth. He had been born on January 1, 1900 – the first day of the 20th century. In 2002, a bronze statue of him was erected in the Little Tokyo district of Los Angeles in the United States.

The Polish Government posthumously awarded him the Commander’s Cross with the Star of the Order of Polonia in 2007.

In Kaunas, the Sugihara Museum now stands what used to be the Japanese Consulate at 30 Vaizgantas Street, which for a short time in the Year of Shame 1940 became the moral capital of the world.

References

Chiune Sugihara. In Wikipedia. Retrieved December 23, 2012, from http://en.wikipedia.org/Chiune_Sugihara.

Gold, Alison Leslie. A Special Fate: Chiune Sugihara, Hero of the Holocaust. New York: Scholastic Press, 2000.

A Japanese Holocaust Rescuer. Retrieved December 23, 2012, from http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=h0lizzqOxuI.

Levine, Hillel. In Search of Sugihara: The Elusive Japanese Diplomat who Risked his Life to Rescue 10,000 Jews From the Holocaust. New York: Free Press, 1996.

Paldiel, Mordecai. “Sempo Sugihara.” In The Path of the Righteous: Gentile Rescuers of Jews During the Holocaust, 252-257. Hoboken, N.J.: Ktav Publishing House, 1992.

Solly Ganor – Remembrance – Ron Greene.Com. Retrieved December 23, 2012, from www.rongreene.com/sollyintro.html.

Sugihara – The Conspiracy of Kindness. 4/6. Retrieved December 23, 2012, from http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ISsybs_89mQ.

Yad Vashem. “Visas to Japan: Chiune Sempo Sugihara.” Retrieved December 23, 2012 from http://www1.yadvashem.org/yv/en/righteous/stories/sugihara.asp.

Sugihara's widow with Lithuania's then president Valdas

Adamkus at

a tree planting ceremony in Vilnius, Lithuania in 2001.

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

Kaunas was an important centre of Jewish life

- Posted by - (4) Comment

Kaunas Synagogue is one of two operating choral synagogues in Lithuania.

Jews are first known to have lived in Kaunas (Kovno) as early as 1410 when they were brought forcibly as prisoners of war by the Grand Duke Vytautas. Many of those Jews were later active as traders between Kovno and Danzig (today's Gdansk, Poland). Living conditions for many Jews were squalid. In 1858, archaic living restrictions were relaxed and all but 6,000 of the city's 35,000 Jews flocked to the Old Town in search of something better. In July 1941, however, the Nazis expelled all the Jews from the town and sent them back to Slobodka. The Kovno Ghetto was thus established.

Kaunas became an important center of Jewish cultural life in the latter half of the 19th century. Distinguished Jewish leaders moved here from Vilnius, the capital, to establish yeshivas. Influential thinkers also moved to Kaunas.

When Vilnius was annexed by Poland during the interwar years, Kaunas became the provisional capital of Lithuania. In 1928, there were 1,000 Jewish students at the Vytautas Magnus University. There was even a Semitic studies program.

In 1931, the Jewish Ethnographic Museum was opened. Within only a few years, it had collected some 3,000 Jewish art works and artifacts. By the mid-1930s there were successful Jewish writers, poets, and artists residing in the city. By 1938, the Jewish population was nearly 40,000 and the area was a booming hub for Jewish businessmen, entrepreneurs, artisans, doctors, and lawyers. Five Jewish newspapers were published daily. There were schools for all ages, adult training centers, theatres, libraries, sports clubs, and political groups. Even the Central Jewish Bank of Lithuania was centered in Kaunas.

Kaunas Synagogue is one of two operating choral synagogues in Lithuania. It is located in Centras eldership, Kaunas. The Neo-Baroque synagogue was built in 1872. In 1902, before the Holocaust in Lithuania, the city had some 25 synagogues and prayer houses.

Dating from 1871, this radically designed synagogue, once one of over 35 synagogues and Jewish prayer houses in the city, claims to have one of the most beautiful altars in the entire Jewish world. A memorial to the estimated 50,000 Lithuanian Jewish children killed during the Holocaust can be found at the rear of the building, complete with 37 stone tablets showing in which towns and cities they lost their lives and just how many of them died in each one.

Kovno video:

Jewish bank in Kaunas

See also: https://vilnews.com/?p=12028

In pre-war Lithuania, many members of the Jewish middle class, especially the educated strata, who had already experienced to some extent the establishing of Jewish autonomy, mobilized their resources for the strengthening of the social economic basis of the Jewish masses and their livelihood. With the blessing and initiation of the Economics Committee at the Ministry for Jewish Affairs and with the assistance of the “Foundation”, a national financial system was established of co-operative credit societies. By the end of 1920, these were already active in 44 cities and towns and were named “Peoples Bank” (in Yiddish Folksbank). In addition to the positive local economic activity (extending loans etc) they were also of importance in the social and cultural sphere. In a number of places, the community organs and other organizations also used the bank building. There were also cases of the bank granting study scholarships and prizes for cultural activities.

In order to co-ordinate and regulate the activities of the Peoples Banks in time of need and crises and other difficulties, a central institution was established in 1921, formally called the “Central Jewish Bank for the Encouragement of Co-operation.” 71 Peoples Banks throughout the country linked to it, and the number of (dues paying) members reached 11,000. Over the years, the capital assets of the institutions increased, as did also the amount of deposits and savings. Thanks to that, the conditions were eased under which the loans were granted to members and public institutions. In 1930, 85 Peoples Banks existed in Lithuania with 22,262 members. In that year, 11,953 loans were granted to them and to others in a total amount of 10,249,159 Lit (approximately one million Dollars).

Although the Peoples Bank was open to non-Jews as well, this figure was no more than 5%. The work in the offices, the correspondence and the daily work routine was conducted in Yiddish, and this was also true of the national conventions and conferences, which took place every few years. This was therefore, a Jewish banking system spread throughout the cities and towns of Lithuania. At that time, the total deposits amounted to 14,113,413 Lit (approximately $1.4 million), of which 46% came from the members, 16% from institutions and 48% from non-members. If we take into consideration the members families and all others requiring the Peoples Banks' services, and that of its associates, then we can conclude that they served about two thirds of the Jewish population. Unlike the similar Lithuanian banks, which enjoyed cheap governmental credit, the Peoples Banks had to depend on deposits only. In 1933, a special bank was established to assist Jewish farmers (Yiddisher Landwirten Bank).

The central office was in Kaunas with 31 branches spread out in towns through the land.

The Central Jewish Bank. Kaunas 1923.

Read more:

http://www.jewishencyclopedia.com/articles/9490-kovno

http://kehilalinks.jewishgen.org/kovno/kovno.html

http://www.northernjerusalem.com/objektai/locations/the-schwabe-hebrew-gymnasium-in-kaunas

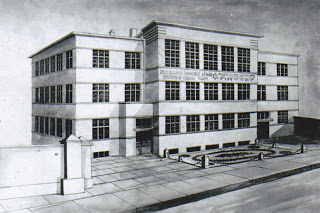

Hebrew Real ("Reali") Gymnasium in Kovno/Kaunas, Lithuania before WWII

From http://aaronrachovich.blogspot.com/2012/01/hebrew-real-gymnasium-in-kovnokaunas.html#.UNq2L-Ssh8E

My father Aaron Rachowitz attended the Hebrew Real/Reali Gymnasium (Kauno žydų realinė gimnazija, today Kęstučio g. 85 [1] formerly Kęstučio g. 59, in front of the theater/Valstybės teatras בית הריאל-גימנסיון העברי בקאונס) in Kovno/Kaunas for four years, i.e., completed four grades/classes: from 1936 to 1940 (the above pictures [2]show the gymnasium building then and today). His younger brother, Nathan Rachowitz, also attended this school. My father's good friend Eliyahu Stoupel (later to become a well known cardiologist in the world -- Professor Eliyahu Stoupel[3]), was his classmate. Most of their friends and classmates were killed during World War II in Kaunas, at Dachau and other locations. Hadassah Gorbulski (the sister of the famous Lithuanian composer Benjaminas Gorbulskis), Shura Katz, David Shein (former EL AL director in New York), Shlomo Yarmovski and Nissim Krakinovski were among those who survived the Holocaust. [4] The school's principal language of instruction was Hebrew but students communicated among themselves in Yiddish. They also studied Latin and Lithuanian. All courses -- except for Lithuanian language, literature and history -- were taught in Hebrew. According to my Dad, the gymnasium was a private institution. If parents do not pay their tuition fee on time (by the due date), the students will be reminded, in front of the whole class, to settle the debt. The gymnasium was on the name of Edward Azriel Chase (Eduardas Čais or Čaisas in Lithuanian), the famous Jewish philanthropist who was born (1874), grew up and spent the greater part of his youth in Tsarist Alytus/Alite (between the two World Wars and since the end of World War II, the town has been a part of Lithuania), but later immigrated to the United States and lived in Manchester, New Hampshire. With his financial help, a new building was erected for the Hebrew Real Gymnasium in 1930 (pictures above) in Kaunas (a formal inauguration dates from August 30, 1931, in the presence of the Lithuanian Minister of Education Konstantinas Šakenis, the mayor/burmistras of Kaunas, Juozas Vokietaitis, as well as Edward Chase and his wife, and many others---250 guests took part in the event), where thousands of Jewish children received their education and Jewish upbringing. The Hebrew Real/Reali Gymnasium had a good academic reputation all over the country (The roots of this gymnasium go back to 1915, i.e., the period of German occupation of Lithuania. Jüdische Realgymnasium was founded by Jewish-German Rabbi Dr. Joseph Hirsch Carlebach, who was charged by the German Occupation Authority in Lithuania with organizing a secondary school system. By the late 1920s, the gymnasium had earned good name but lacked adequate premises, i.e., had been housed in various locations/rented buildings). The total cost of the project, including Chase funding, was estimated in 1931 at 700,000 LT (approximately $70,000). The new gymnasium building (nauji žydų realinės gimnazijos rūmai)accommodated both girls' classes and boys' classes. It had two big halls: the gymnastics hall and the celebration hall; 19 classes; physics cabinet; a technical drawing hall; buffet; 4 wardrobes; 4 rooms with showers. Every floor had twocorridors and etc. [5] The Hebrew Real Gymnasium was designed by Baruch Kling who also supervised the construction. From an architectural point of view, the gymnasium has features derived from the German Bauhaus style or Dutch De Stijl style. [6] Edward Chase also established the Chase Fund that gave dozens of Jewish students the possibility of studying abroad or in Lithuanian universities. In addition, Chase established a scholarship fund to help outstanding students from different religious backgrounds. He contributed much for the development of his native town of Alytus (built houses, awarded scholarships to local students, etc). And his last dream during his visit to Lithuania in 1938 was to turn his former house in Alytus into a Jewish cultural center for Lithuanian youth. At its peak, the Hebrew Real Gymnasium had 40 teachers and 1,000 students. Dr. Zemach Feldstein had been the director of the gymnasium during 1922-1940. By the way, My Dad served as a goalkeeper on the school's football team, defended staunchly the goal and had been called (in Yiddish): "ארקה די הינדשה פלייש" ("Arke die hundische fleisch").

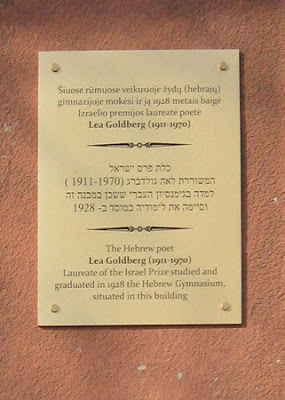

The Jews had enjoyed full cultural autonomy in prewar Kaunas, according to my Dad. In addition to the Hebrew Real/Reali Gymnasium, my Dad also mentioned frequently other Jewish gymnasia and schools that were established in the city: a "Yavne" Hebrew Gymnasium for girls; a "Yavne" Hebrew Gymnasium for boys. Yavne schools were well known for their strong religious education and were partially supported by religious-Zionist Mizrachi organization; a leftist "Commerce" Yiddish Gymnasium (named later after Shalom Aleichem); the Hebrew Gymnasium headed by Dr. Moshe Schwabe and thus called the "Schwabe" Gymnasium (In 1924, Dr. Schwabe immigrated to Eretz-Israel where he was a lecturer in the newly created Hebrew University of Jerusalem and later became its rector. A prolific Hebrew language poet, Leah Goldberg, studied at "Schwabe" Hebrew Gymnasium from 1920 to 1928---please see a commemorative plaque below. By the way, students of the "Schwabe" Gymnasium were sometimes called in Yiddish: "שוואבה די גרינע זשאבע" according to my Dad/"schwabe die grüne zhabe" which means: schwabe the green toad). The Schwabe Gymnasium (the picture of a new building inaugurated in 1927, below) had Revisionist Zionist orientatation; the Hebrew Tarbut Gymnasium affiliated with the Socialist Zionist party Mapai (my Dad's best friend, Dr. Semen Yakobson, at first studied at the Tarbut Gymnasium until 1940, but with the advent of Soviet rule moved to the Shalom Aleichem Gymnasium/previously known as "Commerce" Gymnasium, occupying since the Soviet era the former building of the Schwabe Gymnasium, located on the banks of the Nemunas River [7]---please see the building of the Schwabe Gymnasium, below); Hebrew "Tarbut" schools with strong secular nationalist Zionist orientation. There was also one Jewish gymnasium where students were taught in Lithuanian language. Hundreds of Jewish youth from all over country continued their education in the Lithuanian University of Kaunas (in 1930 the university was renamed to Vytautas Magnus University/Vytauto Didžiojo universitetas). Kaunas had many Jewish associations, organizations, student unions and sports unions, like Maccabi and Hapoel. The Jewish youth joined the Zionist movements like Hashomer Hatzair and Beitar---the Hebrew Real Gymnasium, where my Dad studied, was well known for its support for the Beitar movement, according to my Dad. The young Jews were trained for immigration to and life in Eretz Israel. "Kibbutz Hachshara" (Training Kibbutz) on behalf of "HeChalutz" Zionist youth movement acted in Kaunas. Many of these "Chalutzim" made "Aliyah" to Eretz Israel. The "Tarbut" association initiated public lectures in Hebrew. Throughout the interwar period a Yiddish theater operated in Kaunas. Also, the Jews of Kaunas were privileged to have had theater shows from Poland, the United States and Eretz Israel (the “Habima” theater, "Haohel" theater, etc. Ida Kaminska, for example, performed in Kaunas). A drama studio was run in Hebrew. In the interwar period, more than 100 books in Hebrew were published in Kaunas and etc. Professor Dov Levin wrote that Lithuania's Hebrew educational institutions in the interwar period "not only gave their pupils a solid education in Judaism and Hebrew culture, as well as in the sciences and the arts, but also encouraged them to be active in youth movements, sporting associations, student groups, and training groups preparing to emigrate to Palestine. In fact, Lithuania came to be known as the 'Second Eretz Israel,' in no small measure thanks to the varied and wide-ranging network of Hebrew schools, which was quite unparalled throughout the Jewish world." [8] On a visit to Kovno/Kaunas in the 1930s, the foremost Hebrew poet of modern time, Hayim Nahman Bialik said: "if Vilna is known as the Yerushalayim DeLita [Jerusalem of Lithuania], then Jewish Lithuania should be known as the Eretz-Israel deGaluta [The Land of Israel of the Exile].

____________________________

[1] The Hebrew Real/Reali Gymnasium building now serves as a music school (Kauno apskrities Juozo Naujalio muzikos gimnazija).Dr. Semen Yakobson drew my attention to the fact.

[2] The second photo, by courtesy of Prof. Eli Stoupel. The third photo was found on the web: KVB, Kaunas: Datos ir Faktai. Fotogr. R. Vaitilavičienė (2009 m.).

[3] Please see Prof Stoupel's new book: Space Weather and Timing of Cardiovascular Events, LAP Lambert Academic Publishing, 2012

[4] Information provided by Prof Eliyahu Stoupel.

[5] For further details, please see "Nauja Žydų Kultūrinė Įstaiga: Jos labdarys p. Čais," Rytas, Sept 7, 1931, p 2 viahttp://www.epaveldas.lt/vbspi/biRecord.do?biExemplarId=122209

[6] Northern Jerusalem website

[7] Information provided by Dr Semen Yakobson.

[8] Dov Levin, The Litvaks: A Short History of the Jews in Lithuania, Yad Vashem Publications, 2000

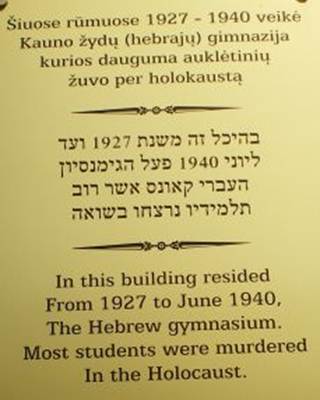

Description: In 1927-1940, this building housed Schwabe (Švabės) Hebrew Gymnasium

(present Karaliaus Mindaugo Ave. 11). 2009. Photo by R. Vaitilavičienė Source: KVB, Kaunas: Datos ir Faktai. Fotogr. R. Vaitilavičienė (2009 m.) Holocaust: Most of its students were murdered during the Holocaust---please see the commemorative plaque below -- D.R.

Source: LitaLita.com

Source: http://atminimas.kvb.lt/iliustracija.php?img=iliustracijos/goldberg_lenta_d

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - (2) Comment

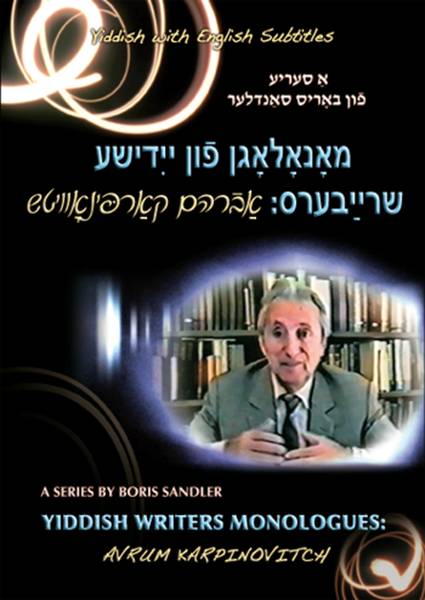

“My writing is about Vilna,” says Abraham Karpinovitch in a new film

Thieves, whores, and gangsters

who supplied color to our lives

By Ellen Cassedy

“My writing is about Vilna,” says Abraham Karpinovitch in a new film – “not about the Vilna Gaon [the renowned rabbi of 18th-century Vilnius] or about the clergy or the intelligentsia, but about the thieves, whores, racketeers, and gangsters who supplied color to our lives.”

The film is the latest in a series about Jewish writers directed by Boris Sandler, the editor of the New York-based Yiddish newspaper Forverts. Sandler presented the film, in Yiddish with English subtitles, at the Lithuanian Embassy in Washington, D.C., on October 18, under the auspices of Yiddish of Greater Washington.

Before World War II, Vilnius was home to 60,000 Jews. Among them were not only scholars, writers, merchants, and political activists – but also a vibrant underclass.

The Vilnius-born Karpinovitch (1913-2004) set about recording and memorializing this multi-colored underworld. To his chosen task, he brought a finely tuned ear for slang, an eye for evocative detail, a talent for blending fact and fiction, and an abiding affection.

As the son of a Jewish theatre director, Karpinovitch was exposed early to the treasures of stage culture. “I feasted on a rich stew of folk cuisine,” he says, “and that’s how I became a writer.”

Before the outbreak of World War II, Karpinovitch immigrated to the Soviet Union, where he was arrested and sent to Siberia. After the war, he settled in Israel. For more than 30 years he managed the Israel Philharmonic Orchestra. “I wore a suit and tie all day,” he says, “then sat down and wrote about the Vilna underground.”

Sandler interviewed and taped Karpinovitch and 20 other Yiddish writers in Israel in 1995.

“Tall Tamare,” a story translated into English by Helen Mintz, tells the tale of a Vilna streetwalker who helps to organize a union for her fellow brothel employees, then behaves with striking dignity at the killing field of Ponar (Paneriai) in 1941. The writer’s work has been translated from Yiddish into Hebrew, Polish, Russian, German, and Lithuanian.

As the chronicler of a bygone world, Sandler said, Karpinovitch “was able to invoke in his own way the mourner’s prayer for his beloved compatriots. He brought his fellow Jews to life so that we, their surviving descendants, could see ourselves in them and remember them.”

Sandler’s film invites viewers to stroll through the old Jewish quarter in present-day Vilnius, where, the director says, “in the streets and alleys and walls and buildings, shadows are looking at us.”

|

|

Her book, We Are Here: Memories of the Lithuanian Holocaust, will appear in Lithuanian in 2013 under the title Mes esame čia: Atsiminimai apie holokaustą Lietuvoje. |

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - (0) Comment

“Ikh bin a vilner,” Samuel

Bak declared, in Yiddish

Ellen Cassedy reporting from Washington D.C.

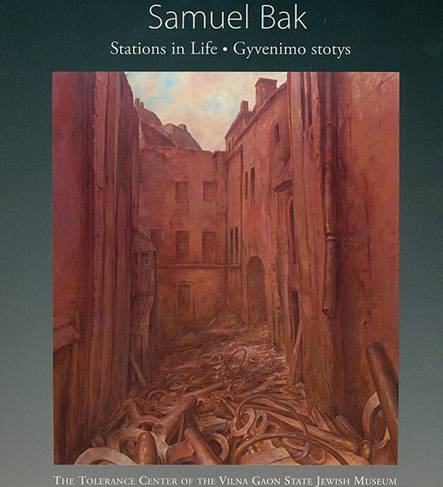

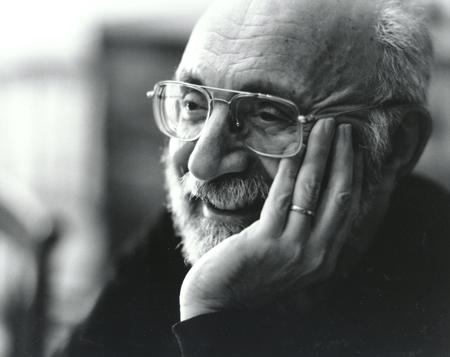

“Ikh bin a vilner,” Samuel Bak declared, in Yiddish, to an audience at the Lithuanian Embassy in Washington, D.C., October 15.

Echoing President John F. Kennedy’s famous statement in Berlin, the artist meant that he is from Vilna, of Vilna – and so is his abundant body of work.

Bak was at the Embassy for the opening of an exhibition of his paintings, which powerfully evoke the city of his childhood – and its destruction during the Nazi era.

Bak was born in Vilnius (then the Polish city of Wilno) in 1933. As a child, he was a part of the city’s vibrant Jewish community of 60,000.

“I grew up as a very conscious Litvak,” he said, “knowing that I was very privileged to be a part of the incredible riches of religious and secular Judaism in this place.”

In 1941, Bak was forced into the Vilna ghetto. There he endured years of hardship, terror, and loss – and was recognized inside the ghetto as an artistic prodigy. His sketches from that period survive.

Of Bak’s family, only he and his mother survived the war. His father and the rest of his relatives perished.

Many of Bak’s paintings evoke the ruins of the old Jewish quarter. Other repeated images, which depict the forces of destruction and repair, are colossal chess boards and giant damaged pears.

Bak left Vilnius after the war to study and paint in Germany, Israel, France, and Switzerland. He lives now in the United States.

In 2001, after more than half a century, the artist visited Vilnius. In his memoir, Painted in Words, he writes that he feared being overwhelmed by past horrors. Instead “a pleasant sensation settled in my soul: the Vilnius of today felt very familiar.” As he walked through the streets, “the ancient city with its winding streets, old buildings, and many restored churches, was more beautiful than I had dared to hope.”

Under the title “The Stations in Life,” or “Gyvenimo stotys,” Bak’s work was exhibited at the Tolerance Center of the Jewish museum in Vilnius earlier this year. Now, the museum has announced plans to create a new Center of Litvak Culture and Art within the Jewish Community building on Pylimo Street. A special gallery will be devoted to Bak’s work. A movie theatre, conference center, and restaurant are also planned.

Speaking of the new center, museum director Markas Zingeris said, “We need to reestablish the Jewish narrative in Lithuania, but we also need to reestablish our common humanity. Art is a way to do that – and Bak is universal.”

|

Ellen Cassedy Ellen Cassedy traces her Jewish family roots to Rokiskis and Siauliai. Her book, We Are Here: Memories of the Lithuanian Holocaust, will appear in Lithuanian in 2013 under the title Mes esame čia: Atsiminimai apie holokaustą Lietuvoje.

|

Samuel Bak

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Samuel Bak (born 12 August 1933) is a Lithuanian-born Jewish painter and writer who survived the Holocaust.

ChildhoodBorn on August 12, 1933 in Vilna - Vilnius, Lithuania, Bak was recognized from an early age as possessing extraordinary artistic talent. He describes his family as "secular, but proud of their Jewishidentity." Immediately following the German invasion of Poland in September 1939, Vilna and the whole East of Poland was attacked by the USSR. After one month though, the Soviets retreated, giving back the city to the Republic of Lithuania. An estimated 30,000 Jews found refuge in the city. As Vilna came under German occupation on June 24, 1941, Bak and his family had to move into the Vilna Ghetto. At the age of nine, he had his first exhibition inside the ghetto, even as massive executions and murders perpetrated by the Nazis and their Lithuanian collaborators took place almost every day. Bak and his mother escaped the destruction of the Vilna Ghetto by seeking refuge in aBenedictine convent. They were helped by a Catholic nun named Maria Mikulska, and spent most of their time there in an attic. By the end of the war, Samuel and his mother were the only members of his extensive family to survive. His father, Jonas, was shot by the Germans in July 1944, only a few days before Samuel's own liberation. As Bak described the situation, "when in 1944 the Soviets liberated us, we were two among two hundred of Vilna's survivors--from a community that had counted 70 or 80 thousand." Bak and his mother as pre-war Polish citizens were allowed to leave Soviet-occupied Vilna and travel to central Poland, at first settling briefly in Łódź. They soon left Poland for good and traveled into the American occupied zone of Germany. From 1945 to 1948, he and his mother lived in Displaced Persons camps in Germany. He spent most of this period at the Landsberg am Lech DP camp in Germany. It was there he painted a self-portrait shortly before repudiating his Bar Mitzvah ceremony. Bak also studied painting in Munich during this period, and painted "A Mother and Son", 1947, which evokes some of his dark memories of the Holocaust and escape from Soviet-occupied Poland. In 1948, he and his mother immigrated to Israel, and four years later he studied art at the Bezalel Academy of Arts and Design in Jerusalem. Bak spent most of his time in Israel studying and living in a modest flat in Tel Aviv and did not paint very much during that period.[1] BiographyThe Family, oil on canvas, 1974 § 1933 On 12 August, Samuel Bak is born to an educated, cultured middle-class family in Vilna. § 1941 On 24 June, the Germans occupy Vilna and order the Jews to wear the yellow Jewish Badge. Bak, aged eight, is charged with preparing badges for his parents and extended family. § 1941 On 6 September, the deportation of Jews to the Vilna Ghetto is initiated. Samuel’s father is sent to a labor camp while the child and his mother flee the ghetto to the home of Janina Rushkevich, his grandfather’s sister who had been baptized in her youth. Janina finds shelter for the family in the city’s Benedictine convent, where the nun Marija Mikulska takes the child under her wing and supplies him with paint and paper. § 1941 When the Germans suspect the convent of collaborating with Soviet forces, they place it under military jurisdiction. The Bak family is forced to flee again, returning to the Vilna Ghetto. § 1943 In March, the poets Avrom Sutzkever and Szmerke Kaczerginski invite the nine-year-old Bak to participate in an exhibition organized in the ghetto. Sensing that their end is near, the poets decide to deposit the Pinkas, the official record of the Jewish community, into the hands of Bak in the hope that they both survive. Paper is a precious commodity and the white pages of the Pinkasbeckon the young artist: he uses them to satisfy his craving to draw. Over the next two years, Samuel fills the page margins and empty pages of the Pinkas. § 1943 Bak’s father is sent to the forced labor camp HKP 526, named after a unit of the Wehrmacht’s Engineering Corps (Heeres Kraftfahr Park). Samuel and his mother are sent to the camp later, upon the liquidation of the ghetto, on 24 September. § 1944 On 27 March, a children’s Aktion takes place in the camp in which 250 children are sent to their death. Bak’s mother takes advantage of the confusion in the camp to flee while Samuel hides under a bed in the living quarters of one of the camp buildings. A few days later, his father smuggles him out of the camp in a sack of sawdust. Outside, by a pre-arranged signal, he links up with a woman waving his mother’s scarf. Janina Rushkevitch saved the family again, sending her maid with the mother’s scarf to fetch the child. Samuel and his mother are forced to look for shelter. Again, they make their way to the Benedictine convent, where they find shelter for 11 months, until liberation. § 1944 On 2-3 July, forced laborers rounded up at the city’s camps, among them his father, are shot to death in Ponary, ten days before Vilna’s liberation. § 1944 After liberation, Bak takes art lessons with academician Professor Serafinovicz, who cultivated the boy’s natural draftsmanship by having him draw from broken plaster casts. As pre-war Polish citizens, the family has the right to return to Poland and so move to Lodz. Bak continues his art studies with Professor Richtarski, an impressionist artist. § 1945 After a short time in Berlin, Samuel and his mother arrive at the Landsberg Displaced Persons Camp. They are greeted by survivor Natan Markowsky, who holds a senior position in the camp’s administration, and will later become Samuel’s stepfather. § 1945 Bak is sent to Munich to study with Professor Blocherer. He frequents the city’s museums and becomes familiar with German expressionism. § 1947 David Ben-Gurion visits Bad Reichenhall, where an exhibition of the art of the child prodigy, Samuel Bak, is organized in his honor. Bak’s art is published in the Hebrew newspaper, Davar HaShavuah, and the Yiddish Forverts in New York. § 1948 Aged fifteen, Samuel arrives in Israel aboard the “Pan York”, carrying with him many artworks from the Landsberg DP camp. § 1952 Prior to military service, he studies for one year at the Bezalel Academy of Art and Design in Jerusalem. § 1953–1956 Military service in the Israel Defense Forces. § 1955 Meets Peter Frye, then one of Israel’s most prominent theater directors, who prompts him to design backdrops and costumes. § 1956 Moves to Paris and enrolls at the École Nationale des Beaux-Arts. Receives the first prize of the American-Israeli Cultural Foundation. § 1959 Moves to Rome. That summer has a solo exhibition at the Robert Schneider Gallery in Rome and exhibits at the Carnegie International in Pittsburgh. § 1964 Exhibits at the Venice Biennale. § 1966–1974 Returns to Israel. § 1974–1977 Lives and works in New York. § 1977–1980 Lives and works in Israel. § 1980–1984 Lives and works in Paris. § 1984–1993 Lives and works in Lausanne, Switzerland. § 1993 Settles in Boston, Massachusetts and is represented by Pucker Gallery. § 2001 Bak returns to Vilna for the first time. During the following years he often visits his hometown.[2] § 2001 Publication of his book Painted in Words: A Memoir, ISBN 0-253-34048-9, which has been printed in four languages. § 2002 Receives the Herkomer Cultural Prize in Landsberg, Germany. Artistic style and influencesWhile Bak's work is complex and difficult to characterize, a few themes stand out: § In Childhood Memories, 1975, the pear, possibly the fruit of knowledge, evokes the loss of paradise and discovery of war. Pear trees are also ubiquitous in many areas of Europe, especially Vilna, where Bak grew up. § The possibility of repair, the repair of a broken world, tikkun olam, is an important meaning contained in many of his still life works. § Bak's childhood frustration with the story of Genesis, and his admiration for the genius of Michelangelo, blend in his post-Holocaust visiting of this theme. § Another artist whose influence is readily seen in Bak's works, such as Angel of the Travelers, 1987, is Albrecht Dürer. § Still lifes—in times when life is never still, never sufficiently protected, nor granted to everyone—attracted him as a metaphor full of symbolic implications. § Chess as a theme of life has always fascinated Bak. In the DP camps and in Israel, he often played chess with his stepfather Markusha. Underground II, 1997, portrays chess pieces in a sunken, subterranean evocation of the Vilna ghetto. § A solitary boy can also be seen in his works. The boy represents his murdered childhood friend, Samek Epstein, and the memory of himself as a child during the Shoah. § In Bak’s 2011 series featuring Adam and Eve (which comprised 125 paintings, drawings and mixed media works), the artist casts the first couple as lone survivors of a biblical narrative of a God who birthed humanity and promised never to destroy it. Unable to make good on the greatest of all literary promises, God becomes another one of the relics that displaced persons carry around with them in the disorienting aftermath of world war. Viewers often describe Bak as a tragedian, but if classical tragedy describes the fall of royal families, Bak narrates the disintegration and disillusion of the chosen people. Bak draws upon the biblical heroes of the Genesis story, yet he is more preoccupied with the visual legacy of the creation story as immortalized by Italian and North Renaissance artists.[3]A a collection of images from the Adam and Eve series can be viewed here. PresentNow 77, the artist continues to deal with the artistic expression of the destruction and dehumanization which make up his childhood memories. He speaks about what are deemed to be the unspeakable atrocities of the Holocaust, though he hesitates to limit the boundaries of his art to the post-Holocaust genre. He creates a visual language to remind the world of its most desperate moments. A collection of Samuel Bak's works are on permanent display at Pucker Gallery in Boston, Massachusetts and many exhibitions of his artwork are held in leading international museums and galleries. Selected publications§ Samuel Bak, Paintings of the Last Decade, A. Kaufman and Paul T. Nagano. Aberbach, New York, 1974. § Samuel Bak, Monuments to Our Dreams, Rolf Kallenbach. Limes Verlag, Weisbaden & Munich, 1977. § Samuel Bak, The Past Continues, Samuel Bak and Paul T. Nagano. David R. Godine, Boston, 1988. § Chess as Metaphor in the Art of Samuel Bak, Jean Louis Cornuz. Pucker Art Publications, Boston & C.A. Olsommer, Montreux, 1991. § Ewiges Licht (Landsberg: A Memoir 1944-1948), Samuel Bak. Jewish Museum, Frankfurt, Germany, 1996. § Landscapes of Jewish Experience, Lawrence Langer. Pucker Art Publications, Boston & University Press of New England, Hanover, 1997. § Samuel Bak – Retrospective, Bad Frankenhausen Museum, Bad Frankenhausen, Germany, 1998. § The Game Continues: Chess in the Art of Samuel Bak, Pucker Art Publications, Boston & Indiana University Press, Bloomington, 2000. § In A Different Light: The Book of Genesis in the Art of Samuel Bak, Lawrence Langer. Pucker Art Publications, Boston & University of Washington Press, Seattle, 2001. § The Art of Speaking About the Unspeakable, TV Film by Rob Cooper. Pucker Art Publications, Boston, 2001. § Between Worlds: Paintings and Drawings by Samuel Bak from 1946-2001, Pucker Art Publications, Boston, 2002. § Painted in Words: A Memoir, Samuel Bak. Pucker Art Publications, Boston & Indiana University Press, Bloomington, 2002. § Samuel Bak: Painter of Questions, TV Film by Christa Singer. Toronto, Canada, 2003. § New Perceptions of Old Appearances in the Art of Samuel Bak, Lawrence Langer. Pucker Art Publications, Boston & Syracuse University Press, Syracuse, 2005. § Samuel Bak: Life Thereafter, Eva Atlan and Peter Junk. Felix Nussbaum Haus & Rasch, Verlag, Bramsche, Osnabrueck, Germany, 2006. § Return to Vilna in the Art of Samuel Bak, Lawrence Langer. Pucker Art Publications, Boston & Syracuse University Press, Syracuse, 2007. § Representing the Irreparable: The Shoah, the Bible, and the Art of Samuel Bak, Danna Nolan Fewell, Gary A. Phillips and Yvonne Sherwood, Eds. Pucker Art Publications, Boston, and Syracuse University Press, Syracuse, 2008. § Icon of Loss: The Haunting Child of Samuel Bak, Danna Nolan Fewell and Gary A. Phillips. Pucker Art Publications, Boston, and Syracuse University Press, Syracuse, 2009. Selected museum exhibitions§ Bezalel Museum, Jerusalem, Israel – 1963 § Tel Aviv Museum, Tel Aviv, Israel – 1963 § Rose Museum, Brandeis University, Waltham, MA – 1976 § Germanisches National Museum, Nuremberg, Germany – 1977 § Heidelberg Museum, Heidelberg, Germany – 1977 § Haifa University, Haifa, Israel – 1978 § Kunstmuseum, Düsseldorf, Germany – 1978 § Rheinisches Landesmuseum, Bonn, Germany – 1978 § Kunstmuseum, Wiesbaden, Germany – 1979 § Stadtgalerie Bamberg, Villa Dessauer, Germany – 1988 § Koffler Center for the Arts, Toronto, Canada – 1990 § Dürer Museum, Nuremberg, Germany – 1991 § Temple Judea Museum, Philadelphia, PA – 1991 § Jüdisches Museum, Stadt Frankfurt am Main, Germany – 1993 § Hebrew Union College, Jewish Institute of Religion, New York, NY – 1994 § Janice Charach Epstein Museum and Gallery, West Bloomfield, MI – 1994 § National Catholic Center for Holocaust Education, Seton Hall College, Greensburg, PA – 1995 § Spertus Museum, Chicago, IL – 1995 § B’Nai B’Rith Klutznick National Jewish Museum, Washington, DC – 1997 § Holocaust Museum Houston, Houston, TX – 1997 § Panorama Museum, Bad Frankenhausen, Germany – 1998 § National Museum of Lithuania, Vilnius, Lithuania – 2001 § Snite Museum of Art, Notre Dame University, Notre Dame, IN – 2001 § Florida Holocaust Museum, Saint Petersburg, FL – 2001, 2007, 2009 § Canton Museum of Art, Canton, OH – 2002 § Clark University, Worcester, MA – 2002 § Neues Stadtmuseum, Landsberg am Lech, Germany – 2002 § University of Scranton, Scranton, PA – 2003 § City Hall Gallery, Orlando, FL – 2004 § Texas Tech University, Lubbock, TX – 2004 § Tweed Museum of Art, University of Minnesota, Duluth, MN – 2004 § Felix Nussbaum Haus, Osnabrueck, Germany – 2006 § University of New Hampshire, Durham, NH – 2006 § Yad Vashem Museum, Jerusalem, Israel – 2006 § Mary and Leigh Block Museum of Art, Northwestern University, Evanston, IL – 2008 § Sherwin Miller Museum of Jewish Art, Tulsa, OK – 2008 § Keene State College, Cohen Holocaust Center, Keene, NH – 2008 § Brown University, John Hay Library, Providence, RI – 2009 § Wabash College, Eric Dean Gallery, Crawfordsville, IN – 2009 § DePauw University, The Janet Prindle Institute for Ethics, Greencastle, IN – 2009 § Drew University, Korn Gallery and University Library, Madison, NJ – 2009 § Queensborough Community College, Holocaust Resource Center, Bayside, NY – 2009, 2010 § Holocaust Memorial Center, Zekelman Family Campus, Farmington Hills, MI – 2010 § Holocaust Museum Houston, Houston, TX - 2012 External links§ Facing History and Ourselves § University of Minnesota, Center for Holocaust and Genocide Studies § Yad Vashem, The Holocaust Martyrs' and Heroes' Remembrance Authority References1. ^ Painted in Words: A Memoir, Samuel Bak. Indiana University Press, Bloomington, Indiana, 2002. ISBN 0-253-34048-9. 2. ^ Samuel Bak: Life Thereafter, Eva Atlan and Peter Junk. Felix Nussbaum Haus & Rasch, Verlag, Bramsche, Osnabrueck, Germany, 2006, p. 84. ISBN 3-926235-26-8. 3. ^ Samuel Bak’s Adam and Eve: On Holocaust and Beauty, Maya Balakirsky Katz. Pucker Art Publications, Boston, 2011, p. 2. |

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - (0) Comment

Irene Veisaite is this

year’s recipient of the

Goethe Medal

Chairwoman of out VilNews Honorary Council, literature professor and critic Irena Veisaite is a recipient of this year's Goethe Medal.

Once a year, the Goethe-Institut awards the Goethe Medal, an official decoration of the Federal Republic of Germany. This medal honours foreign personalities who have performed outstanding service for the German language and international cultural relations. The Goethe Medal was established by the executive committee of the Goethe-Institut in 1954 and acknowledged as an official decoration by the Federal Republic of Germany in 1975.

Since it was first awarded in 1955, a total of 326 personalities from 58 countries have been honoured.

Read more about the award and Professor Irene Veisaite:

Deutsche Welle Jüdische Allgemeine Goethe Institut

VilNews (Ellen Cassedy) VilNews (Aage Myhre)

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

Visit Žagarė, northern Lithuania, this weekend

- Posted by - (0) Comment

Former Žagarė synagogue.

INVITATION TO A VERY SPECIAL EVENT IN ŽAGARĖ

Under the initiative and leadership of a Lithuanian activist Valdas Balčiūnas, A MEMORIAL PLAQUE TO COMMEMORATE THE ZAGARE JEWISH COMMUNITY will be unveiled. The ceremony coincides and may be considered to be taking place in the context of ZAGARE CHERRY FESTIVAL which will be held in July 12-15. The plaque will be in English, Lithuanian, and Yiddish. Here is what the English version will say:

The festival begins on July 12, 2012. Here are some highlights of Jewish interest:

• Dedication of the memorial plaque -- Friday July 13 at 1600 in the Zagare Town Square

• "From the History of the Shtetl"– a presentation, exhibition, and concert organized by the Joniskis Municipality Museum -- Friday July 13 at 1700 at the Zagare Culture Centre

• Baltic senior football (soccer) competition including the Makabi team from Vilnius – Saturday July 14 at 1300.

Please let us know if you are planning to attend. We look forward to seeing a strong representation of descendants of the former Jewish community of Zagare. After the official events there will be a FRIDAY EVENING GATHERING AND 'KABBALAT SHABBAT' FOR VISITORS. If you wish to be invited to this please let us know.

For more information please contact any of the following:

UK - Joy Hall (joy@joymaynard.myzen.co.uk)

LITHUANIA -Valdas Balciunas (valdas@me.com)

U.S. - Cliff Marks (c.v.marks@att.net)

ISRAEL - Sara Manobla (manobla@netvision.net.il)

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

The first time I heard the name of Žagarė

- Posted by - (0) Comment

Žilvinas Beliauskas

By Žilvinas Beliauskas

Manager of Cultural Projects

Vilnius Jewish Public Library

The first time I heard the name of Zhagare (Žagarė) it was probably like for many Lithuanian kids related to cherries – Zhagre cherrys. Big and juicy ones. There were some of such trees in my parents’ orchard. Zhagare liqeuer came later. Maybe even later than mom‘s notice about St. Barbara of Zhagare (Barbora Žagarietė) from 17th century, though not beatified yet but very revered in Samogitia (Žemaitija) as a real saint in charge of many miraculous healings. And that was it for many years until it turned out that the family of my wife comes from Zhagare. During the first walking tour with her I enjoyed marvelous streets of wooden houses along river Shvete, radiating strange and sadly atractive kind of romantic atmosphere of brick houses around the Central Square. The architecture prompted straightforwardly that they used to belong to Jews and association with the direction sign by the road at the entrance to Zhagre showing the way to the Graveyard of the Jewish Genocide Victims made this atmosphere still blurry ghostly, not quite tangibly yet but bringing a distant smell of its “echos and absences” to use Roger Cohen phrase in his letter to the forthcoming event this Friday.

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

Echos and absences

- Posted by - (0) Comment

Roger Cohen

By Roger Cohen,

Columnist, International Herald Tribune and New York Times

I look forward with considerable emotion to returning to Zagare for the unveiling of a plaque that will commemorate the slaughter of more than 2,250 Jews in the town on October 2, 1941. More than three score years and ten have gone by since that mass murder without full acknowledgment of its scope. The men, women and children taken from the main square into the woods to be killed have remained anonymous, mere shadows, their fates at first concealed by Soviet political calculation and taboos, and then only falteringly recognized after Lithuania gained independence in 1990. I do not know the Jews who were killed but I know that each of them valued life and its joys as we do, and I know that my grandmother, Pauline (“Polly”) Soloveychik would have been among them had she not left Zagare for South Africa in the early 20th Century. For me, the fate of the Zagare Jews is personal.

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

Ellen Cassedy |

The book We are Here |

Daiva Markelis |

Professor Daiva Markelis, Illinois: Essay/review of Ellen Cassedy's book We Are Here

I’ve always been interested in Lithuanian history and, lately, in Jewish-Lithuanian history. Jews have been living in Lithuania since the 1300s, have contributed to the work of nation building throughout the centuries, suffered alongside their Christian neighbors during the reign of the tsars. Despite their once considerable numbers—over seven percent of the population at one time—and formidable achievements, I don’t remember ever reading about them in Lithuanian Saturday School vadoveliai, readers filled with patriotic poems, variations of stories about the founding of Vilnius involving a dream about an iron wolf, and photographs of storks nesting atop the thatched roofs of simple country cottages. (Every year the same stork seemed to appear in yet another edition of the book.)

At home, my mother talked about a Jewish friend she’d had in Klaipeda. My father remembered a Jewish peddler who sold fabric and buttons. So, yes, Jews had lived in Lithuania, but only a handful over six centuries—that’s the impression I received. Soon after Lithuania regained her independence, I learned from my Aunt Birute about the once-thriving Jewish community in Dusetos: “This was a grocery store,” she said as we walked down Kazys Buga Street, “and here stood a bakery, and beyond that, over there, the best restaurant in town.”

I tell the Dusetos story to Ellen Cassedy, author of We Are Here: Memories of the Lithuanian Holocaust, recently published by the University of Nebraska Press, over coffee at the Corner Bakery. She nods: “The collapse of the Soviet Union made it possible for people to speak openly about what happened during the occupation. During both of the occupations, Communist and Nazi.”

Ellen had emailed me a few months earlier, having gotten my name from a mutual acquaintance who knew I’d be at the Association of Writers and Writing Programs Conference in Chicago. She is a warm, elegant woman with a crown of curly blond hair, a good listener and asker of questions, befitting her background as a journalist. I’ve been acquainted with her for all of thirty minutes and already she knows that both my first language and first husband were Lithuanian, that I’ve kept my maiden name, that my second husband is of Bohemian and Greek descent (and a keeper), that my parents immigrated to the United States in the 1940s, that I’ve visited Lithuania four times. I know that Cassedy’s Jewish great-grandmother had worked on a dairy farm, supervising the Lithuanian workers and keeping the books; that her grandfather had been a religious scholar, that he had escaped to the United States to avoid the czarist draft.

We’ve talked about the perils and pleasures of publishing books and the highs and lows of academic conferences.

“What do you think of Val Adamkus?” she asked, referring to the former president of Lithuania and a long-time resident of Hinsdale, Illinois.

“I love Adamkus. I used to work as a waitress at a golf resort he owned in Michigan back in the Seventies. He was a friend of my father’s.”

“Do you know Al Domanskis?” she continued.

“There’s one degree of separation for Lithuanians living in Chicago. So, yes.”

Domanskis is a prominent Lithuanian lawyer and activist involved in efforts to promote Jewish-Lithuanian dialogue.

Other Lithuanians we know (or know of) include Julija Sukys, whose Epistolophilia: Writing the Life of Ona Simaite, also published by the University of Nebraska Press, recounts the struggles of the Vilnius librarian who helped save Jews and was deported to Dachau; Ina Navazelskis, who works in the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum; and Saulius Suziedelis, the noted professor and historian who writes extensively about the Holocaust in Lithuania.

As our talk shifts to the Holocaust, I realize I’m a little worried for Ellen. Not all Lithuanians will greet her book with the interest, respect, and admiration of the above-named individuals.

“You’re going to receive some flak,” I say.

“Really?” she says, sounding sincerely surprised.

Perhaps I’m being presumptuous. I haven’t read the book yet, after all. And one of the blurbs on the back is by Adamkus, a man highly respected, even idolized, by a large number of diaspora Lithuanians. Adamkus writes that We Are Here "can help us to reach out, open our hearts, and rediscover one another in the spirit of mutual understanding."

But I know from experience that Lithuanian complicity in the Holocaust is a topic most Lithuanians wish would just go away. Some deny that Lithuanians were involved in the massive killings, despite countless eyewitness accounts and historical research from a wide range of highly respected scholars. Others bring up ethically questionable not to mention specious counter-arguments: “The Jews were communists and thus responsible for the take-over of Lithuania by the Soviets.” Still others fear that acknowledgment of any involvement will be seen by susceptible minds as an admission that Lithuania, a small, relatively poor country with a history of occupation, was the instigator of the Holocaust.

The most frequent response is that Lithuanians have endured their own significant losses: the massive deportations to Siberia; the death of family members to starvation and disease in that vast, unforgiving region; the enforced Russification of the entire country. “What about us?” is the sometimes unspoken reaction to real or imaginary accusations. The trauma of war, displacement, and occupation make it difficult to see beyond one’s own sufferings, to realize that victims can also be victimizers.

Back home in Charleston, Illinois, surrounded by cornfields and Baptists and a university newspaper whose motto is, somewhat inexplicably, Tell the Truth and Don’t be Afraid, I crack open We Are Here and am immediately drawn into the book’s narration.

Cassedy begins by describing her first days in Vilnius during the summer of 2004. One of her reasons for visiting Lithuania was to study Yiddish, the mother tongue of her forebears. I suspect that more than one reader will identify with her struggle to learn foreign syntax and vocabulary. How many individuals born in the United States or Canada to Lithuanian parents haven’t felt that seven cases for Lithuanian nouns are six cases too many?

Cassedy’s intimate beginning, with its emphasis on the intricacies of language learning, works to make readers more emotionally receptive when she shifts to what might be termed the more momentous reasons for her trip: to uncover family secrets about her Uncle Will, who served as a Jewish policeman, a morally controversial post, in the Siauliai ghetto during the Nazi occupation; and to chronicle how Lithuania has been dealing with its turbulent wartime past. Choosing to start with less “heavy” subject matter may be a carefully considered (and highly effective) rhetorical move, but it is also a hallmark of Cassedy’s chosen genre. We Are Here is not an academic history, nor is it a traditional memoir; it can best be described as an ethnographic chronicle of discovery, a book where personal experience is seamlessly integrated with in-depth interviews and formidable historical research. In addition, the sections about Uncle Will make this a detective story in the tradition of Dostoevsky’s novels, where the circumstances surrounding a crime create suspense but are ultimately less important than the psychological motives and moral dilemmas underpinning the perpetrator’s actions.

In We Are Here, Cassedy weaves a complex and colorful tapestry where certain themes emerge, then recede, then appear again. Her encounter with Steponas, an old man from her ancestral town of Rokiskis, who wants to “speak to a Jew” before he dies, parallels in some ways the anguished history of her uncle. Reading this section brought to mind the famous quote by Edmund Burke: “All that is necessary for the triumph of evil is that good men do nothing.” Steponas had been a witness to the executions, had done “a little” to help out his Jewish neighbors. Cassedy writes: “It seemed to me that it was his anguish about whether he could have done more that had led him to want to speak to me, and then to weep before me.”

The individuals Cassedy meets during her summer journey—Lithuanian gentiles, Lithuanian Jews, her fellow classmates at the language institute—are depicted with a writer’s eye for detail and a humanist’s desire for understanding the motivations of ordinary people. This doesn’t mean Cassedy is blindly accepting—there is nothing Pollyannaish about We Are Here. We see her irritation when someone says something contradictory or just plain idiotic, though this is almost always portrayed with raised eyebrows rather than harsh words.

We Are Here is not always easy reading. How could it be, with such serious, often tragic, subject matter? But it is not emotionally overwhelming reading. Cassedy structures her book so that readers can digest broader historical events and think about their implications while at the same time immersing themselves in the writer’s personal quest to unearth family information and navigate a new country. The writing itself is masterful— honest, uncluttered, evocative, and often highly poetic, as when Cassedy describes Rokiskis: “My ancestral home. Except for the trilling of birds, the town seemed hushed, suspended like a held breath. There was so much air. Somehow my images of the past hadn’t allowed for so much blank space.”

This is an especially important book for English-speaking Lithuanians who live in the West and are unaware of the slow but steady progress that is being made in Lithuania with coming to terms with what happened during the Holocaust. There is so much to learn, so much that needs to be done in terms of writing Lithuanian Jews back into the history that had been so brutally taken away from them. We Are Here is a great starting point.

|

|

Ellen Cassedy traces her Jewish family roots to Rokiskis and Siauliai. Her new book, We Are Here: Memories of the Lithuanian Holocaust, was published in March and will appear in Lithuanian soon. She lives in Washington, D.C. Visit her website at www.ellencassedy.com.

|

|

|

DAIVA MARKELIS Born in 1957 in Chicago to Lithuanian immigrant parents and raised in Cicero, Daiva Markelis has found unexpected contentment amidst the cornfields of Central Illinois. She is an associate professor of English at Eastern Illinois University, where she teaches creative writing, composition and rhetoric, women’s memoir, and myth and culture. She is a cofounder of Past/Forward, a memoir-writing group open to the public that meets twice a month and consists of ordinary people, many of them retired, writing moving, insightful, often humorous life stories. |

|

Daiva received her doctorate from the University of Illinois at Chicago in Language, Literacy, and Rhetoric. Her dissertation deals with the literacy habits and oral traditions of Lithuanian immigrants; chapters have been published in the journals Written Communication and Lituanus, and in the edited volumes Ethnolinguistic Chicago and Letters across Borders: The Epistolary Practices of International Migrants. Daiva has presented her research at the Modern Language Association, the Conference on College Composition and Communication, the Association for the Advancement of Baltic Studies, and the National Council of Teachers of English. She has also written several academic papers in her native Lithuanian. Her master’s degree is in English with a specialization in creative writing, also from the University of Illinois at Chicago. Daiva’s short stories have been published in Cream City Review and Other Voices. Her creative nonfiction has appeared in The Chicago Tribune Sunday Magazine, The Chicago Reader, Crab Orchard Review, Writing on the Edge, Women and Language, Mattoid, Agora, and Fourth River. Mongrel Tongue was a finalist in the 2007 Arts and Letters competition in creative nonfiction. The Lithuanian Dictionary of Depression was a runner-up in the 2009 American Literary Review creative nonfiction contest. The Review published the essay in its Spring 2010 issue. Daiva is married to Marty Gabriel, a retired social worker for the Chicago public schools and a top-ranked Scrabble player. Marty and Daiva have appeared in Scrabylon, Scott M. Petersen’s documentary about tournament Scrabble. Daiva cheers for the White Sox. She loves to knit, scrap-book, read, and listen to music, everything from Bach, Beethoven, and Brahms to bebop, bluegrass, Brel, the Band, and the Black Eyed Peas. Her favorite color is red, her spirit animal is a polar bear, her astrological sign is Capricorn. She wants a puppy for Christmas.

|

|

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

“Why do you love Jews so much?”

- Posted by - (14) Comment

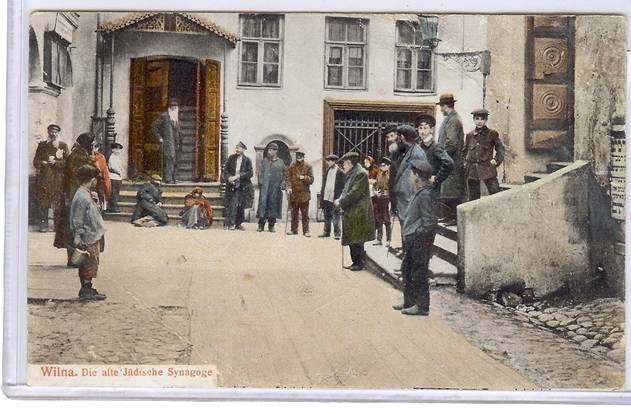

Vilnius, the old Jewish Synagogue.

By Aage Myhre, Editor-in-Chief

aage.myhre@VilNews.com

I have repeatedly been asked, by Lithuanians and others why VilNews, and I as a Norwegian without a single drop of Jewish blood, love Jews so much? Recently I met a Lithuanian-American, well educated and well read, who yet bombastically trumpeted. "You lick the asses of the Jews, Aage."

During my meetings with Jews in South Africa, where 90% of the Jewish population of almost 100 000 are of Lithuanian descent, I have also been asked why I have such great interest in Litvaks.

My answer to all these, has been that I do not love Jews more than other peoples.

But I also tend to add that I am always impressed by people who achieve more than the common herd. Intelligence and wisdom are to me among the most important qualities a person can have, and I have no problem admitting that these are qualities I've seen a lot of among the Jews I have known through life.

As to the Litvaks, they were subjected to an almost total extinction here in Lithuania during the Holocaust. It was an assault and a genocide of an unimaginable scale that we must never forget, and which memory must find its fair balance in the mental as well as in the practical.

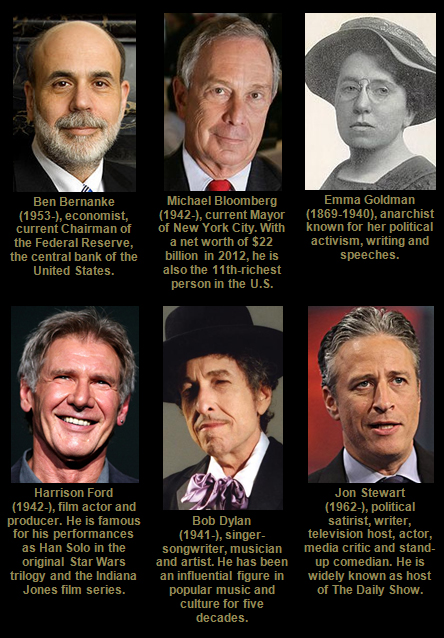

On 4 April, the United States and many other countries welcomed the decision of the Government of Lithuania to appoint a fund for Jewish property compensation, calling it an important historical step toward justice.