THE VOICE OF INTERNATIONAL LITHUANIA

|

VilNews has its own Google archive! Type a word in the above search box to find any article.

You can also follow us on Facebook. We have two different pages. Click to open and join.

|

Why this perpetual

return to Lithuania?

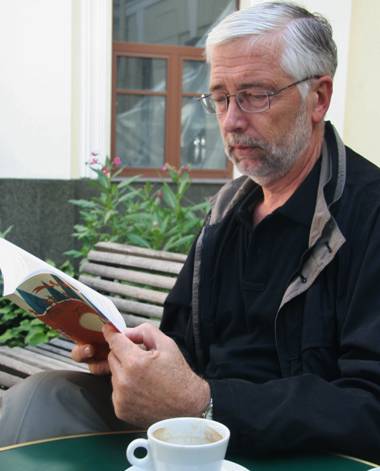

Novelist Antanas Sileika on the Traku - Pylimo street corner

in Vilnius – with his book Underground.

Photo Aage Myhre

Standing on the corner

of Traku and Pylimo

A writer muses about the foreign sources for

his work and what it means to be a Canadian

By Antanas Sileika, novelist

For the fourth year in a row I’m standing at the crossroads of Pylimo and Traku Streets in Vilnius, Lithuania, worrying the place, trying to sift the stories that lie like dust between the cobblestones. I’m slightly sick of this baroque, labyrinthine city - the strangulated cries of the swallows at dusk make me think of the dead souls of forgotten citizens.

Nobody who lives in Vilnius now had great grandparents who lived here - most of the old inhabitants were killed during the war or shipped out after it. Vilnius is old, but the people who inhabit it are relatively new to this city.

They came here after the war, around the time I was born to immigrant parents in Toronto. Although I’ve spent my whole life in Canada, my clan, my people are new to it, and I’m not entirely comfortable in the country of my birth. I keep coming back to this melancholy city of Vilnius, mulling over the past and trying to determine the geography of my belonging.

I’ve never been to Newfoundland or Saskatchewan. I once had fantasies of drinking my way through the Okanagan Valley or of searching out whatever commercial fishermen remain on the great lakes in order to ship out with them. These are oversights I might never remedy, fantasies I’ll never realize.

I’m a fifty-six year-old Canadian, and as much as I would like to write about the place where I live, I keep writing instead about the past and the place my parents came from. I’m slightly embarrassed by this fact, all too aware of then disdain many people hold for historical writing.

Immigrants in the fifties were called “Displaced Persons”, or DP’s for short. I’m undergoing some sort of reverse DP process, being pushed back in time and space. My life has become a time machine, stuck in reverse.

Someone my age should have a clearer view of his place in the world, but the complicated strands of history are getting more and more complicated as I grow older, more tangled.

So why this perpetual return to Lithuania, land of rolling green hills so similar to Southern Ontario? For one thing, the stories here in the old country are so much more brutal, the stakes so much higher than back in Canada. Placed beside the gulag, suburban angst is pitiful. And then there’s the fact that my family history keeps appearing in unexpected places.

Antanas Sileika's book Underground

I have just come from a meeting with Bernardas Gailius, a young historian who wrote a magazine story about my uncle, Pranas, a man who died in 1952, the year before I was born. My late parents remembered him as the family joker, the must-have guest at any party.

They never did mention that Pranas strangled his lover in 1931, hid her body in a sewer, and hoped to dissolve her remains with acid from a laboratory where he and his cohorts were making a bomb to overthrow the Lithuanian president.

Such a dark story! My uncle was a murderer. Do I carry his blood in my veins?

And there are some oddities to his story - Pranas only got three years for the crime (extenuating circumstances? What could those possibly have been?). Part of his sentence was to support his son by the murdered lover. Somewhere I may have a cousin whose mother was murdered by our common relative. Should I look for this lost cousin? What could I possibly say to him?

To make matters worse, the man pictured in the magazine article photo as “Pranas” seemed to bear an uncanny resemblance to his brother, my father. I stared long and hard at that photo until I realized I was not just seeing family resemblance. I was looking at a photo of my father, not my uncle.

The photograph of the murderer was a photograph of my father.

I’d just met with the historian to ask if my father had actually been the murderer, but the historian said no. There had been an error at the magazine and they had inserted my father’s prison photo by mistake. This new information was both a consolation and a troubling new revelation. On the one hand, my father was not the murderer. That was a relief.

But his prison photo?

It turns out my father had been imprisoned for being part of the same cabal of political malcontents, rebels and potential assassins.

I hadn’t ever heard any of this before.

It made me wonder what else I didn’t know about my deceased parents’ lives. I would have to spend some time in the archives if I wanted to find out because there was no one left with living memory of those events.

But I was in no rush to get to those particular archives. Most people no longer believe that the sins of the fathers are visited on the sons, nor the sins of the uncles visited upon the nephews, but still, one hopes for a little glory in the past, or at least a little righteousness. I felt shaken.

Rather than go back along Pylimo Street to the archives, I could go forward to the Jewish museum.

If my “bad” uncle Pranas had been a shock to find out about, a skeleton whose bones would continue to rattle for a while, I preferred to investigate the past of my other uncle, the one I was named after.

During the Nazi occupation of Lithuania, he had hidden some Jewish boys in his house. This happened during a very bad time because the holocaust was particularly brutal in Lithuania, where so many Jews were killed by Nazis and local collaborators.

At least three of the children my uncle sheltered survived the war. His widow, my aunt, still has a letter of thanks from one of the their fathers. I keep a copy of this letter as a kind of talisman, a good luck charm against the horror of the past.

Danute Selcinskaya, head of the Righteous Gentiles’ Commemoration Department, met me on the top floor of the Vilna Gaon Jewish State Museum, where she kept an office among a dim warren of rooms.

She had a file on my “good” uncle, some scrap of proof that confirmed his actions. If I gave her more information, she could start the process of searching for the saved boys and if they were found, to begin the process to have my uncle named a Righteous Gentile.

Thus if I went one way on Pylimo Street, I could look into the dark past of the first uncle. If I went the other way, I could look into the story of at least one decent person. Is it no wonder these stories attract me? I need to settle some kind of issue of good and evil, if any such settlement is ever possible.

But that isn’t the end of the story, because I am standing at a crossroads. Thus there are two other ways I could go.

If I head up from Traku Street, I will end where I am staying, with relatives of my wife. They are Saulius and Silva Sondeckis, she a cellist trained by Mstislav Rostropovich and he the most prominent chamber music orchestra conductor in the Soviet Union and independent Lithuania.

They are both master storytellers as well, so as we sit and sip tea and eat home-churned butter and white Lithuanian cheese, Saulius has described the darkly comic era of the fifties, especially during the rule of Joseph Stalin, when everyone lived in fear. His stories sometimes have funny or surreal spins to them. For example, the leader of the Lithuanian Communist party stood up after one of Saulius’s concerts featuring the music of Johann Sebastian Bach, turned to the audience and said, “Now that’s what I call Communist music!”

No further explanation was given or asked for, and the approval opened many doors. The chamber orchestra grew in stature in concerts throughout Europe, Asia, and North America. Once, a Moscow concert was held in near-darkness because it was attended by international Communist subversives whose identities had to be kept secret.

I imagine Che Guevara in the dark hall, boning up on culture before heading into the Bolivian jungles to meet his death. And Saulius is there in his tails and baton, leading the orchestra. The frisson of politics and culture is extraordinary, and this story is only one of dozens that Saulius and Silva have told.

These are the sorts of stories that have pulled me back more and more often to Lithuania. The stories compel me, but they unmoor me as well. Canada is the haven my parents found after the war, yet I don’t feel strongly anchored here. If my parents were cast upon a safe shore after the tempest of WW 2, I have sat on the beach my entire life, wondering about their loss. At times, I have set out to sea in my imagination and drifted, living in neither one land nor the other. At times I felt as if I might drift away forever.

But if I have described three routes available to me at the crossroads, each of them into the past, I have not yet described the fourth route, down Traku Street into the heart of old Vilnius. I walk past the ancient mansion of the Tiskevicius family, whose portico roof is held up by a pair of titans in plaster, and I descend into the maze of streets in this uneasy city.

Not far from the dawn gate, where a miraculous painting of the Virgin Mary is adored by pilgrims on their knees, I find a bearded young man with a cigarette between his lips and a sleeve tattoo covering his left arm. He looks a little tired, but otherwise well, this son of mine whom I have not seen for three months, since he deployed out of Val Cartier to fight with the Canadian Army in Afghanistan.

My relief at the sight of him is made acute by the knowledge that he is on leave, only halfway through his tour of duty, which involves carrying a grenade launcher as a corporal in battle group. He laughs a little as I embrace him, and we go into a café to find out how it has been. There we will drink scotch and beer, talk of the ever-present ringing in his ears and a couple of close calls I will not describe to his mother until he returns from his tour of duty. I use the word “until”, but I hover over the word “unless.”

His choice is not one we wanted him to make or even approved of, but we found ourselves impotent in the face of his decision to delay his education at McGill. And so I stood helpless before the face of history that was playing out in front of me, much as it had played out for my uncles, good and bad, and for my hosts in Vilnius, the Sondeckis family.

A new story was unfolding for me now, with stakes just as high as the stakes from the stories in the past. And the effect of this story is to moor me to Canada more firmly than I have ever been moored here before, more strongly than any accident of birth.

If my son should die in battle, he wants his ashes to lie in a military cemetery in Ottawa. Although he lives his life less dramatically, my other son will likely be buried here too when his time comes.

If I have been unsure about my home, unsure of where I belong all these decades long, these two young men are the ones who have pointed out the answer to the question I’ve been asking for most of my life.

It’s not all that unusual, to have my children rather than my parents determine my homeland. It happens to immigrant families all the time. Maybe it just takes a little longer than we ever imagined, just one more generation than we thought.

Late in my life, I have become a fatalist. The currents of history keep on pulling us in various directions regardless of our puny desires. And history isn’t just the past. History is happening right now, for me in a café in Vilnius where my past meets my future in a conversation with a bearded young man in a sleeve tattoo.

(postscript - Originally published in Queen's Quarterly in 2011. Antanas Sileika's son survived the posting in Afghanistan, and has gone on to marry and plans to pursue further studies in Lithuania. The search for records of Antanas Sileika's "good" uncle has run into some hurdles and is ongoing. Antanas himself has had his most recent novel, Underground, translated as "Pogrindis" by Versus Aureus in Lithuania. The novel has been optioned for a film by Donelos Studija. Antanas is doing research for a novel based on the life of Soviet Lithuania's leader, Antanas Snieckus. For all his professed Canadianess, Antanas spends more and more time in Lithuania.

Antanas Sileika is a Canadian novelist and critic.

He was born in Weston, Ontario - the son of Lithuanian-born parents.

After completing an English degree at the University of Toronto, he moved to Paris for two years and there married his wife, Snaige Sileika (née Valiunas), an art student at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts. While in Paris, he studied French, taught English in Versailles, and worked as part of the editorial collective of the expatriate literary journal, Paris Voices, run from the upstairs room of the bookstore, Shakespeare and Company.

Upon his return to Canada in 1979, Antanas began teaching at Humber College and working as a co-editor of the Canadian literary journal, Descant, where he remained until 1988.

After writing for newspapers and magazines, Antanas Sileika published his first novel, Dinner at the End of the World (1994): a speculative story set in the aftermath of global warming.

His second book, a collection of linked short stories, Buying On Time (1997) was nominated for both the City of Toronto Book Award and the Stephen Leacock Award for Humour, and was serialized on CBC Radio's Between the Covers. The book traces the lives of a family of immigrants to a Canadian suburb between the fifties and seventies. Some of these stories were anthologized in Dreaming Home, Canadian Short Stories, and the Penguin Anthology of Canadian Humour.

Antanas Sileika appears occasionally on Canadian television and radio as a free-lance broadcaster.

His third book, Woman in Bronze (2004), compared the seasonal life of a young man in Czarist Lithuania with his subsequent attempts to succeed as a prominent sculptor in Paris in the twenties.

His latest novel, Underground was released by Thomas Allen & Son in spring of 2011. The new novel is a love story set in the underground resistance to the Soviet Union in the late 1940s.

He is the director for the Humber School for Writers in Toronto, Canada, and is a past winner of a National Magazine Award.

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

VilNews e-magazine is published in Vilnius, Lithuania. Editor-in-Chief: Mr. Aage Myhre. Inquires to the editors: editor@VilNews.com.

Code of Ethics: See Section 2 – about VilNews. VilNews is not responsible for content on external links/web pages.

HOW TO ADVERTISE IN VILNEWS.

All content is copyrighted © 2011. UAB ‘VilNews’.

Click on the buttons to open and read each of VilNews' 18 sub-sections

Click on the buttons to open and read each of VilNews' 18 sub-sections

Dear Tony,

Just a note to let you know how much I enjoyed the essay above. I feel bad it's been around since 2011 and I hadn't seen it. (Bankers don't read Queen's Quarterly, I guess. At least not this one!) Thanks to Aage for allowing it to appear here. The essay gives an articulate voice to rather similar but jumbled thoughts rattling around and bothering me in my own head. But that's what fine writers and storytellers are about after all. Thank you.

Rimantas Aukstuolis