THE VOICE OF INTERNATIONAL LITHUANIA

|

VilNews has its own Google archive! Type a word in the above search box to find any article.

You can also follow us on Facebook. We have two different pages. Click to open and join.

|

Culture & events

- Posted by - (2) Comment

A

By Jurate Kutkute Burns

Florida, USA

My most recent visit to Lietuva concluded on September 24th of this year. It was my fifth visit since I first saw my parents’ homeland in 1998 and I can honestly say that each time I come, my appreciation and love for this country grows. Several of my friends in Lietuva have asked me what I think of their country, or city, as they wish to compare their vista with that seen by an outsider. These are my impressions, colored in part by my own parents’ views of what Lietuva meant to them.

First, Lietuva, while geographically small, has an enormous investment in artistic and intellectual capital. Artists, musicians, poets, writers and teachers are appreciated for their talents. Vilniaus Senamiestis is truly an architectural treasure, and each year more of the decayed buildings are being refurbished. Valdovu

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - (0) Comment

Berta upe Tilmantaite

is among the world's

top photographers

OLEG – THE HUNTER IS A MOVIE BY BERTA UPE TILMANTAITE

SEE HTTPS://VIMEO.COM/81331998

By Aage Myhre

When I spoke with Berta

Berta upe Tilmantaite is a Lithuanian multimedia journalist, photographer and story teller, currently based in Vilnius. She obtained her MA in International Multimedia Journalism from the University of Bolton / Beijing Foreign Studies University (Beijing) after graduating from Vilnius University.

Recently the Asia-Europe Foundation (ASEF) organized an international photography competition "On the Go", and Berta up Tilmantaitė won first place with her photo “On the boat”

B.Tilmantaitės winning photograph will be exhibited in Luxembourg during the 12th Asia-Europe Meeting (ASEM) Foreign Ministers 'Meeting (12th ASEM Foreign Ministers' Meeting).

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - (4) Comment

GameChanger

A film about Lithuania's

nonviolent resistance

By Aage Myhre

aage.myhre@VilNews.com

American-Lithuanian Rima Gungor (25) will reside in Lithuania throughout this summer to conduct a series of interviews and recordings that will crystallize in a movie planned launched to a worldwide audience in March 2014. The film bears the name GameChanger, and will shed light on Lithuania's postwar fights against occupying superpowers from the start of World War II until the final independence in the early 1990s. An important point will be Lithuanians remarkable nonviolent and successful uprising against the Soviet invaders in 1990-1991.

“Yes, the idea is to chronicle and analyze the history of resistance movements in Lithuania and show how and why they developed into the final and successful non-violent resistance movement,” she tells us.

“While at North Central College in Chicago I won a Richter grant which allowed me to research and complete a paper on Lithuania’s resistance movements. I wrote my thesis on nonviolent resistance movements and how they can be successful using Lithuania’s nonviolent movement as an example. The nonviolent resistance movement in Lithuania is one of the least recognized and least talked about freedom movements, however, it was one of the most successful in several decades.”

The film will analyze Lithuania’s freedom movements starting from the armed resistance during and after World War II, the protests during the 1960’s and 1970’s, and finally the nonviolent movement in the 1980’s and 1990’s. The goal is not only to tell Lithuania’s story, in a historical, but also personal and intimate way through interviews with participants both inside and outside of Lithuania, and to apply it to a global context to inspire other movements around the world.

Here is what Rima has to say about her background and reasons for making this movie:

While at college, I wanted to write about this part of Lithuania’s history in a broad sense, however I decided to narrow down the topic to the peaceful resistance movement in the 1980’s and 1990’s and use it as a successful example of Dr. Gene Sharp’s academic approach to nonviolent resistance. I used the grant toward a three week research trip to Lithuania. It had been almost four years since my last trip to Lithuania and my first time traveling internationally on my own.

In those three weeks, I had learned more about our history than from any book I had ever read. I really wanted an in-depth look at the peaceful resistance movement and to not only read about, but also discuss its success with those directly involved. During my research trip, I was lucky enough to interview Vytautas Landsbergis, Angonita Rupsyte, Dr. Gene Sharp, and many others involved in Lithuania’s independence struggle. These personal, face to face interviews helped me gain greater insight into how the peaceful resistance movement came to be and what factors led to the decision to remain nonviolent.

When the Soviets reoccupied Lithuania in 1944, Lithuanians decided to defend their nation by using force. That partisan resistance movement was severely crushed with impunity. The last partisan resistance fighter was caught and killed in 1956.

Many of the partisans fighting during Lithuania’s long and bloody ‘guerilla war of 1944-1953 were young men returning to Lithuania from the West to fight for their beloved home country. Here are three of them, with their official and nick names: K. Sirvys - "Sakalas", J. Luksa - "Skirmantas", B. Trumpys - "Rytis". Very few ‘Western partisans’ returned to their homes in Europe or the U.S.. Almost all of them were killed by the Soviets.

After the armed resistance movement ended, Lithuania went through a period of uncertainty with respect to resistance efforts in the 1960’s and 1970’s. Underground movements started to form and the human rights protests began, publicly highlighted by the self-immolation of Romas Kalanta in 1972. The groups that formed were not connected under one banner for some time due to differences in viewpoints and logistical issues. It was not until 1988 that a unified movement of diverse groups was formed under Sajudis. One point that was understood amongst all of the members was that nonviolent resistance was the method they would use to gain Lithuania’s freedom and independence. As Vytautas Landsbergis put it to me in our interview, “violence did not work in our favor the last time so we knew we had to try peaceful resistance. It was the only logical choice.”

The protest movement took on several public forms including large gatherings, public demonstrations, singing of Lithuanian cultural folk songs in the streets, throwing Soviet paraphernalia in piles in the streets, etc. Behind the scenes the work to organize and keep the movement moving forward was difficult and dangerous, especially since independence was not the end goal but the structure of the country under democratic guidelines was. Once independence was gained it would require even more commitment and hard work to maintain it.

Then came the night of January 13th, 1991, also known as the January massacre. At this point, Soviet tanks and soldiers had entered into Lithuania as a sign of aggression against Lithuania’s peaceful resistance movement. The people took to the streets, stood in front of the tanks, protested, but never once turned violent in any fashion. Soviet soldiers continued the act of aggression and ended up killing 13 civilians. Some were run over by Soviet tanks. It was a gruesome evening that only ended once Gorbachev was persuaded by members of his staff that it was best to end it. This act of aggression by the Soviet Union was not received well by the West. It showed the USSR to the world as the evil empire it was portrayed as.

I returned from my trip and immediately got to work. My uncle had to ship the 30 odd books I bought in this enormous box because I could not carry them home! I was absorbing as much about Lithuania’s history as I could in order to do it justice in my thesis. While I was in Lithuania, I decided to record all of my interviews on camera so it would be easier for me to integrate the quotations into my paper. About eight months later, I was sitting with my grandmother eating lunch when she paused for a moment and said, “Rima, you recorded all those interviews you did, correct?” I nodded and asked her if she wanted to see them. She replied, “Well of course, but I think the rest of the world just might want to see them too. You’re sitting on a pretty high mountain of history, you know.”

What she said stuck with me for about a year before I decided that it was finally time to do something. The catalyst was actually another documentary called The Other Dream Team. While that documentary focuses on the story of basketball and Lithuania, it also touched on the difficulties of Soviet occupation, the peaceful resistance movement, and Lithuania’s relentless push toward freedom. It was around that point in which I decided that it was time to tell our story. However, I didn’t just want to tell it to our community, I wanted to apply Lithuania’s success to a more global context and show others that peaceful resistance is a viable option to gain freedom and independence. And that rather than a glamorous, idealistic effort that succeeded by using songs it was a long, difficult, dangerous road requiring hard work discipline, commitment, and the will to move forward in spite of all the obstacles that could have brought it down.; that every sacrifice was worth it; and that every struggle for independence does not end with its declaration.

I took the plunge to make this documentary on March 20th of this year when we launched our Facebook page, website and Kickstarter page. The positive feedback has been overwhelming and with each interview I do reinforces my need to tell our story. I am also very lucky to have the dedicated team that I have. They are with me every step of the way and believe in this project as much as I do. Our Kickstarter page was fully funded four days early, making a little over $10,000 in about 27 days. We were thrilled and we know our second Kickstater round will be just as successful. Currently, we are wrapping up our North American interviews. We have filmed in Toronto, Chicago, Madison, Cleveland, Lansing and Seattle. We depart on June 10th to Lithuania to film interviews, collect archive footage, and film historical sites. We expect to return September 10th and immediately move into production to have the trailer ready for November of this year. We expect the film to be ready by March or April of next year. It has been an incredible experience so far and we cannot wait to continue our next part of the journey. To find out more, visit our website and Facebook page at www.gamechangerfilm.com and www.facebook.com/GameChangerFilmLT. We will have our new Kickstarter link on both pages once it’s ready. This Kickstarter round will go for three months instead of 30 days. We would like to thank everyone for their support of our endeavor!!

|

Rima Gungor (25) about her relations to Lithuania

I come from an old family. My family, the Tallat-Kelpsai, suffered as a result of the occupation. Part of my family experienced incarceration in the labor camps and deportation to Siberia, and the other part fled and were in displaced persons camps for five years while waiting for some country to take them in. In those days immigrants had to have a sponsor that guaranteed that they would not be a burden on the U.S., had to pass health exams, etc. so it could take quite a few years to be able to leave the DP camps. Once here the adjustment was not easy, especially for the dispossessed immigrants. They could not communicate with close family in Lithuania so they did not know for long periods of time what happened to them, they could not go home until Lithuania became free, and they were completely unfamiliar with the nation they had emigrated to with almost nothing. Although some of my family spoke English and were university educated, their education was not accepted fully by their new homeland which made making a living harder. And within a short time of being here, although not yet a citizen, one was drafted into the US Army, so the family lost an important member while beginning to put down roots. My family which remained in Lithuania struggled as exiles, and upon returning to Lithuania. Both parts of my family survived, struggled, and continued to be good as well as successful people. As a child, people in the U.S. did not ask me so much about Lithuania; it started more when I was a teenager and as I became older and went to university. Most of the time, I would speak about Lithuania in history or political science classes and at conferences where my paper was accepted, explaining the history, about the occupation and its relevance to and the impact on the international community. This year I will be presenting at the Baltic Studies conference in Estonia on the Lithuanian independence movements. Americans interest varied. There was greater interest when they knew someone who was Lithuanian, were basketball fans, or had read about it or seen a film and had questions. They are interested in hearing about Lithuanian basketball and its stars, swimming, and technology especially due to the success of GetJar. I usually stress the importance of Lithuania’s history the most, but also its achievements of the past 20 years, and its art, culture, and food- both in Lithuania and the diaspora. I talk about its beauty, the preservation of its historical landmarks, and nature reserves, the ocean and its beaches, its forests, its museums and unusual spots. I discuss its flaws and its strengths. I feel deeply connected to the culture - it has been a big part of my life for many years through folk dance, academics, cooking, reading, programs like LISS and Refresh Lithuania and family and friends. Lithuania means home wherever I may be.

|

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - (5) Comment

ANCESTRY

By Daiva Markelis, Charleston, Illinois

Professor of English at Eastern Illinois University

When I was growing up, my mother was always going on about her aristocratic roots. Her great-grandfather had been a Prussian plikbajoris. Bajoris comes from the word bajoras, meaning nobleman, while plik is a shortened form of plikas, or naked. A naked nobleman was one whose wealth had dissipated, usually through fiscal mismanagement augmented by an excessive fondness for liquor.

Not to be outdone, my father would counter with the claim that his surname—Markelis—was one of a kind. “Except for my siblings, no other Markelises roam the face of earth,” he’d add, as if we were dinosaurs.

I felt doubly blessed. Having a singular last name was just as special as being the great great-granddaughter of Prussian plikbajoriai.

As an adult, I never really questioned my father’s claim. In all of my formal and informal studies of Lithuanian history, literature, and linguistics, I never came upon the name Markelis. Decades of involvement in Lithuanian-American life and multiple visits to the homeland did nothing to dispel this notion of familial exclusivity—I never met another person bearing my last name.

Then, one morning, about a year ago, I logged onto Facebook to find the following message:

Hello Daiva Markelis, my apologies for not good english speach. But I just wanted to say, that its gratifieing to see people with same surnames. I have read some articles that you have wrote about Lithuania. It is great. Sorry, if I wasted some of your time.

The message was signed by a Rimantas Markelis. His Facebook photograph revealed a very fit, good-looking young man with the same dark eyes and intense expression of my father.

I thought I’d be disappointed to lose my unique Markelis status, but all I felt was curiosity and a tinge of existential relief.

We quickly friended each other and exchanged a few messages. I wrote in grammatically questionable Lithuanian, Rimantas in charmingly imperfect English:

I have never been in America but I think its much easier life, than in Lithuania. Its hard to find a job in these days, even if you have some graduates, everything depends how many friends you have in any institution.

I felt like writing back: “That’s pretty much the way it is in Chicago,” but held back.

Soon another Markelis popped up on Facebook. I assumed that Tomas was Rimantas’ brother. The idea that there might be more than two Markelis clans did not cross my mind until several weeks ago when I examined the FB pages of both and realized that not only do the two look nothing alike, but they also hail from different cities; Rimantas, who reminds me of my father, was born and raised in Alytus, halfway across the country from Dusetos, my father’s birthplace. Tomas, who looks nothing like my dad, lives in Rokiskis, a mere seventeen miles away from Dusetos.

My curiosity piqued, I decided to see what other Markelises had put down roots on Facebook. I thought there might be another two or three, and was shocked to discover thirty-one in all, the majority of them men. There were several Greeks—an Iraklis and Spiros and Grigoris. There was a Pablo Markelis, a lawyer who’d graduated from the University of Michigan and had gone to USC film school. Of course, there were plenty of Lithuanian names on the list: Mindaugas, Mintartas, Marius, Algedas, Rimgaudas, Darius, Egidijus, Arunas.

As for women, there was a Rosanna with rigid FB settings, an Alesia who was clearly Greek, and a woman I’ll call Elena. I thought Elena might be Lithuanian, but then discovered she’s from Buenos Aires and now lives in Florida. Her Facebook wall reveals that she is strongly pro-Israel and has a daughter who’s a member of the Board of Temple B’nai Brith. Elena may be related to Pablo. Although they are not FB friends, they have several Silvermans in common.

My searches on Facebook just whetted my appetite for finding more Markelises. The next step was Ancestry.com, because “you never know what you might learn about the past.” I have friends who love Ancestry—I’d always thought of them as individuals with too much time on their hands. I signed up for the free one-month trial and was hooked immediately. Ancestry revealed that one family of Markelises had immigrated to the U.S. from Lithuania in the early 1900s and settled in Massachusetts; another, in Pennsylvania. The Markelises on the first two pages of the Ancestry listing have Christian first names: Mary, Veronica, George, John, etc.

Further down the listing, I discovered a Yenca Markelis and Googled it only to learn on names.whitepages.com that “ZERO people in the United States have this name.” Soon after Yenca came a Yetta Markelis, then a Tavel and a Herschel and a Meyer, all from Lithuania. An entry simply labeled Markelis stated that the name appears on the Jewish Surnames List for the area of Minsk, Lithuania’s neighbor to the east. Khaim and Bassia Markelis had the following note appended to their names: Holocaust Refugees Relocated to Tashkent. And Boruchas Markelis, who died in 1920, was born and raised in Rokiskis, the same place as Tomas.

I’ve since learned that a variation of Markelis is Margelis. The letter k, when in the middle of a Lithuanian word, sounds almost like a g. Margelis would be a descriptive surname—margas in Lithuanian means colorful. Marge is also a very popular cow’s name, the Lithuanian equivalent of the American Elsie. So, maybe my father’s ancestors were a colorful lot. Or maybe they just owned a lot of cows.

Speaking of descriptive Lithuanian surnames—they are the most fascinating in the world, in my completely non-biased opinion. Among my favorites are Baltakis (white-eyed one); Baltaragis (white-horned one); Kairys (left-handed one); Repecka (one who crawls on all fours.) The name of tennis ace Ricardas Berankis presents an interesting nominal conundrum, since berankis means one without hands. And I imagine a forefather of the great basketball player Zydrunas Ilgauskas stretched out on the grass, relaxing. “Wow. You sure are long,” a passing villager exclaims, and thus a name is born.

Back to Markelis, or Margelis, which sounds a lot like Margolis, one of the most common Jewish surnames from Belarus, Lithuania, and northeastern Poland. When I researched the meaning of Margolis, I discovered that the name means ‘pearl’ in Hebrew. Ancestry.com qualifies this by stating that “the Hebrew word is ultimately of Greek origin, as in Greek margaron, margarites [for] ‘pearl’.”

When I told a Chicago friend with Eastern European Jewish roots about my possibly Jewish surname, I expected a modicum of surprise, perhaps even guarded approval. She just shrugged her shoulders and said something like “Oh, we’re all interconnected.”

Another friend, the writer Ellen Cassedy, whose wonderful We Are Here: Memories of the Lithuanian Holocaust serves as a model of genealogical research, wasn’t surprised when I told her what I had discovered about my name. “That's what occurred to me when you said you were searching,” she wrote in an email. “That the name could be Jewish. Or maybe German?”

I hadn’t even thought of German. Another avenue of research to pursue. Dusetos, my father’s birthplace, is not far from the Latvian border. Pockets of the country once had significant German populations. My father’s first name was Adolfas, the Lithuanian version of the very German Adolph, a popular name in the 1910s. And Markelis sounds like Merkel, as in Angela Merkel, the current German chancellor. I did a Google search of Merkel, which lead me to Markel. According to HouseofNames.com, Markel comes from the Germanic marah, or horse (mare); it’s probable that early Markels were servants who looked after horses.

Later in the same entry, however, the writer claims that the very first Markels lived in Prussia and were “one of the most notable families in the region” (emphasis mine.) The site sells a large number of Markel-related items, including a large, hand-painted plaque “proudly displaying the Markel crest” for $201.95. Those unwilling to shell out that kind of money can buy a mouse pad with the Markel coat-of-arms for $16.95 or a coffee mug for $13.95. I thought of buying the mouse pad, carefully inking in IS after the MARKEL, and showing off my coat-of-arms to envious friends.

What sweet irony it would be if my father had descended from the noble Prussian Markels—though that’s a pretty big if. The class differences between my aristocratic mother and more humble father were an occasional source of contention. “You Valaityte, you!” my father would spew as if it were an expletive when my mother criticized his rambunctious manner when he had too much to drink. My mother’s life of piano lessons and trips to Sweden and Traviata on New Year’s Eve stood in marked contrast to my father’s depressing childhood. He rarely talked about his past, except to say that his family was poor and his father drank and his mother was illiterate. Both were shipped off to Siberia despite their abject poverty and my grandfather’s collectivist politics. There was never any talk of my father’s grandparents. They were nameless individuals, probably deceased by the time my father was a boy.

What else I discovered about Markels from the internet: there are quite a few Jewish Markels, many of them living in Argentina. And Markel has over one hundred spelling variations, including Mark, Marcos, Marek, and Markowitz. The Internet Surname Database only lists a few, and Markelis isn’t one of them.

I often ask my college students what they’ve learned in the process of researching a paper topic: What do you know about your subject that you didn’t know before? What have you learned from this experience?

I ask myself the same questions.

I discovered that more Markelises roam the earth than were dreamt of in my philosophy.

I found I can spend hours on Ancestry.com, forgoing sleep and paper grading.

The existence of the Jewish Markelises confirmed my belief that although Lithuanian Christian and Lithuanian Jewish communities lived in highly segregated communities, there must have been points of intersection when more than a love of herring was shared.

I learned I might be of noble heritage on both sides of the family, which should give me some special privileges, such as discounts at Lithuanian restaurants.

More probably, however, I’m the descendent of people who looked after horses or raised cows. The percentage of commoners is much smaller than that of nobles, even in aristocrat-laden Lithuania.

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - (0) Comment

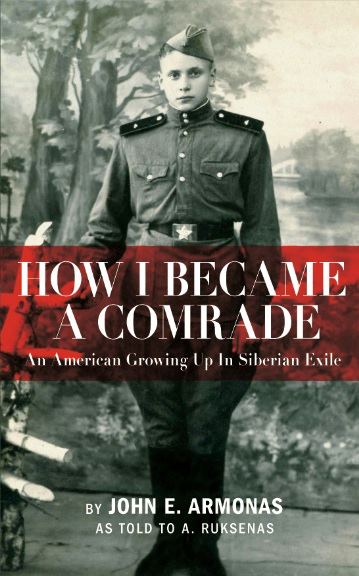

An American growing

up in SIBERIA

NEW BOOK: "How I Became A Comrade:

An American Growing Up In Siberian Exile" by John E. Armonas

as told to Algis Ruksenas, is NOW AVAILABLE thru Amazon.com.

An American child deported with his mother to Siberia, torn from her when she is given additional punishment at hard labor in the notorious GULAG, is raised as a Soviet in order to survive.

John Armonas was a U.S. citizen, but had been left behind when his American-born father and five-year old sister, Donna, were urged to leave Lithuania back for the United States, after the Soviets first occupied Lithuania in 1940. His mother Barbara, a native Lithuanian, was assured by American officials she could soon follow with nine-month old John, as soon as her immigration papers were expedited. Instead, they ended up in Siberia in one of the massive waves of deportation from Lithuania and other Soviet occupied countries after World War II. John became Ivan, an "orphan", with his past hidden, because his mother's alleged political offenses would have cut off all chances for his survival, let alone any opportunity for success within the Stalinist system. A dramatic public encounter by his sister, Donna, with Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev during his visit to America in 1959, elicited from him a promise to let her mother and brother leave the Soviet Union and be reunited, ending a separation of 20 years, but not without additional bureaucratic harassment. This is a true story of survival, adaptation, and ultimate triumph over injustice.

Facebook page: https://www.facebook.com/HowIBecameAComrade

„How I Became A Comrade: An American Growing Up In Siberian Exile“ is available at Amazon and Barnes & Noble

John E, Armonas (right) at age 13 and his friend standing in front of a statue of

Lenin and Stalin at Lake Shira in Kazakhstan in 1953.

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

The strange phenomenon of Eurovision

- Posted by - (0) Comment

Eurovision for Lithuanians is like one more religion after basketball. Everybody has their opinion on everything: how the artist should look, how they should move on the stage, what the song should be, how it should be performed. The strangest thing is that with such a big group of experts, somehow we pick the wrong person every year.

Every year lots and lots of groups and single artists fills out applications to participate in the Eurovision song competition. Every year thousands of people are watching the National Finals to vote for the best song and finally win. And every year right after the results of the National Final the weirdness begins.

After announcing the results of the National Final in one night the chosen one becomes the worst one. After getting the majority of the votes from the TV viewers, the chosen artist becomes the most criticized person in whole country. It’s seems that overnight everybody changes their opinions or that during the voting process everybody was in some kind of trance. There has never been a person that would win the National Contest and would still remain the favorite.

The reverse process is happening in Eurovision’s semi-finals. If our representative, that no one believed in, gets through to the finals the whole country becomes believers. After the semis people regain hope and after promising last place jumps to the top 10 or says „Didn‘t I say so?“. And that lasts for two days. After that, back to believing in last place.

Eurovision brings that strange emotion in peoples lifes when we are able to be the bigest optimists and pesimist at the same time. We wish and hope for the best places, we vote for the best national song, and at the same time we are so afraid to confes that we are believers that we start to declare our pessimism instead. It‘s easyer to say that we will loose and enjoy the winning then hope for the best and cry in the end.

This year everything was as usual. No one liked Andrius Pojavis, but somehow he was elected. No one believed in him, but after wining in the semi-final everyone was saying that this is how it should be. In two days everybody was promising him the last place again. After attention from journalist from abroad, Lithuanians also started to believe in top 10. The bigest shocker this year though, was not being close to last, but not geting votes from the UK and Latvia. Lats are our neighbors and we were always generous to one another in a matter of points. In the UK, the biggest number of emigrants from lithuania are in the UK, and if we are expecting any votes it‘s from countries that lithuanians lives in.

I think what I‘m trying to say is that we should not be afraid to say loud and clear that we are believers and actually belive and suport those who are representing us. Because if even we won‘t belive in them, then who will?

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - (0) Comment

Lithuanian genius artist

Marija T. Rožanskaitė

I attended an amazing gallery tour by Laima Kreivytė, the curator of the exhibition of Marija Teresė Rožanskaitė’s work. I had seen some works by Rožanskaitė at the National Gallery of Art earlier, and I thought that she was among the most interesting Lithuanian artists of all times, but the current exhibition gives a full picture of her genius. Rožanskaitė (1933-2007) started her career under Soviet censorship, when artistic expression was carefully monitored and abstract art was treated unfavorably. However, her ‘progressive’ topics (modern medicine, space exploration and industrial cities) allowed her to get through the censorship. However, being a child of political prisoners and a progressive artist, she was largely ignored in the USSR. When Lithuania became independent, the artist continued producing innovative art, creating spatial assemblages and installations, addressing ecological and political topics, adored by the young generation. And yet I never studied about her work at art history lessons, and I heard nothing about her death in 2007 from the mainstream press. It’s a typical way to treat women artists.

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - (0) Comment

The land I lead you to

is Lithuania

SMALL IS THIS LAND,

But great is its truths. To be. To survive. To testify by itself to the abundance and variety of the world’s nations, to the value of man’s life in freedom in his homeland.

PAINFUL IS THIS LAND,

Each blade of grass here sprouts from a drop of blood or a tear.

TOILFUL IS THIS LAND,

In the sandy soil of a hillock it grows both grain and graves marked with crosses.

BRAVE IS THIS LAND,

It went from uprising to uprising, from exile to exile, from deportation to deportation. A great number of its people were laid to rest in the permafrost of Siberia, some of their bones were flown back to their native soil, the survivors lost their health in slave labour, but returned home.

BEAUTIFUL IS THIS LAND,

Over each hillock, over each forest and over each lake it looks the same and different. It is just like our folk song: Though over the Nemunas river it seems to be sung in a different manner, it is nevertheless filled with the same longing and poignant emotion.

Justinas Marcinkevičius

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - (1) Comment

Justinas Marcinkevičius

(1930-2011)

Justin Marcinkevičius Važatkiemio in his native village in 1986.

Photo: Romuald Rakausko.

Marcinkevičius was born in 1930 in Važatkiemis, Prienai district. In 1954 he graduated from Vilnius University History and Philology faculty with a degree in Lithuanian language and Literature. He joined the Communist party in 1957. He worked for a number of years as vice-chairman of the board of the official Union of Lithuanian Writers. He died in Vilnius on the 16th of February 2011.

Having grown up during the post-war period, Marcinkevičius evokes in his poetry a romanticized version of childhood spent in the Lithuanian countryside, of first love, of man's relationship with nature. In his poetry specific and solid peasant thinking is combined with a mind seeking to draw broad general conclusions, and the tradition of Lithuanian poetry singing the Earth's praises with contemporary modes of poetic thought. As a poet, he has sought to grasp the essence of national experience and give it fresh artistic expression. In his lyrical verse Marcinkevičius strives to comprehend the real meaning of what is going on inside man and society and moves the reader with his ardent lyrical confessions.

For most his life Justinas Marcinkevičius lived and wrote during the complex times of Soviet totalitarianism. He defended the cultural self-awareness of his nation. The poet brought back humanistic idea in describing a man, continued on the romantic and lyric poetry tradition, valued the aesthetic side of literature, as opposed to the heroic and propagandistic style of socialist realism. Marcinkevičius wrote poems in a romantic and modern style. Justinas Marcinkevičius is regarded as one of the most prominent members of Sąjūdis.

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - (0) Comment

Rescuing a Photo Prince

From Obscurity

By JULIE TURKEWITZ, NEW YORK TIMES

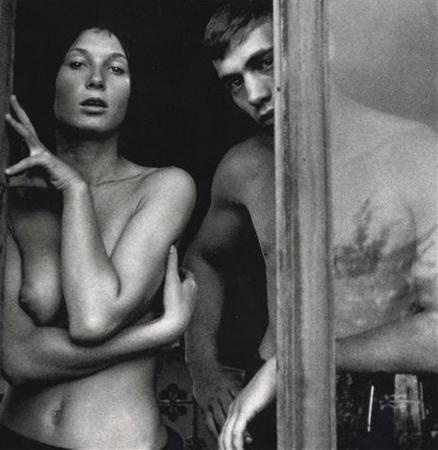

Tanya Aldag slips into a closet-size room in her home in suburban Maryland. The door clicks shut. Here, surrounded by thousands of black and white prints, she goes tumbling back to Soviet-era Lithuania.

“It’s like you’re going deep into the water,” she said. “It can be hard to go there.”

Ms. Aldag, 64, is the widow of Vitas Luckus, once a prince — perhaps even a king — of the Soviet photography scene. From the 1960s to the mid-1980s, he traveled throughout the Soviet bloc, capturing peasants, performers, partiers and policemen, as well as a generation of grippingly attractive young artists. He scurried across sloping rooftops (Slide 15), camera swinging from his neck. He worked obsessively, with little care for what others thought. The secret police were a constant presence in his life, burgling his home and beating him in bathrooms and cafes.

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - (6) Comment

Making Bullets:

Take One California Girl

add a Lithuanian Revolution

and Stir

The true story of Daiva Venckus, a young American’s journey to her ancestral homeland during the collapse of the Soviet Empire.

Making Bullets is the inspirational story of a California-born woman who travels to her family’s homeland to learn about her heritage and becomes a part of Lithuania’s “Singing Revolution” against Soviet occupation.

On January 13th, 1991 fourteen peaceful protestors were killed and hundreds of others were injured by Soviet troops as the unarmed citizens stood, arm in arm, singing—protecting Lithuania’s Parliament building and the nation’s main communications tower. The lines held against the tanks that day. The Soviets didn’t succeed in their coup attempt but they didn’t end Lithuania’s drive for independence. Two days after the massacre 25 year old Daiva Venckus arrived in Lithuania, offering her services to help her beloved ancestral home. Eventually she began work as a press spokesperson for the Lithuanian Parliament. On August 19th, the Soviet army attempted another coup. While Gorbachev was held hostage, tanks surrounded the Lithuanian Parliament building where Daiva and others were barricaded for a final last stand.

Thankfully Daiva has written a book about her experiences during this period

The book is the true story of her life as the American-born daughter of Lithuanian immigrants who believed it was her sacred duty to preserve their language and culture until the day Lithuania could be free of Soviet rule.

Her fondest childhood memories were making ‘bullets’ (a nickname for traditional Lithuanian meat dumplings “koldunai”) with her great grandmother, “Sena Baba”. She often told her, “Tradition is our weapon.” Her days were filled with family stories about the homeland. Their lives centered on Lithuanian activities: folk dancing and singing, Lithuanian Saturday School, Lithuanian scouts and endless commemorative gatherings where everyone cried about the loss of the homeland. She didn’t know she was an American until her first day of nursery school when she realized that she didn’t speak English—it her first introduction to American society.

Eventually she grew tired of conjugating verbs fifty-two different ways, reciting 100 year-old poems and being forced to perform in nineteenth-century embroidered peasant clothes at the annual Potato Pancake Ball. What was the point to it all? She wanted to go to the mall. She wanted to go surfing. She wanted to hang out with her American friends. Eventually she rebelled and drifted away from the Lithuanian community.

As perestroika emerged in the USSR, the cause of freedom for Lithuania unexpectedly became her passion. She had connected to something bigger than herself - She had meaning in her life. The fact it was a cause her family had tried to force on her for all those years didn’t matter, because it had become her cause by choice.

She traveled to Lithuania on a student archeology visa in July of 1989. The land she only knew from Saturday School books and family stories finally came alive. But she also saw how her beloved Lithuania was damaged through decades of “Sovietization.” Revolution was in the air and she wanted to be a part of it.

In January of 1991, in the midst of the revolution, she bought a one-way plane ticket to Vilnius. She was determined to help even though she had no idea how. She was surprised the Soviets at the border allowed her to enter the country. She just showed up and asked, “Where can I help?” This question meant translating documents, a brief stint as an English-speaking TV newscaster, a music radio show host, an MC for a benefit concert, and eventually volunteering for the revolutionary freedom movement, Sajudis.

She wasn’t prepared for the food shortages, looking for toilet paper on the black market and the escalating Soviet military violence on the streets. As months went by, she dealt with the stress and uncertainty by taking her Czech motorcycle with a sidecar out for long rides in the countryside, much to the amusement of Lithuanians who had never seen a woman on a motorcycle before.

It was chance that caused her to be working inside the barricades of the Lithuanian Parliament as a press spokesperson. Her skill was being able to speak and write both English and Lithuanian fluently. The days she spent conjugating all those verbs in Lithuanian Saturday school back in LA was finally paying off. For several months it was a race against escalating Soviet military aggression to get information out to the West before the Iron Curtain shut down on Lithuania once and for all.

On August 19th, the Soviet military went in for the final deathblow to Lithuanian Independence. When Gorbachev had been taken hostage, kicking off the Moscow coup, she was 300 miles from Vilnius in a resort town on the Baltic Sea for a break from all the stress. The only way out was by ferry to the mainland. As I watched people pile up in buses and taxis, she knew she had to escape before she was trapped, so she jumped into the street in front of a taxi and offered the driver all her money to drive her to Vilnius. For five hours they negotiated Soviet checkpoints through torrential rain, searching for gas to complete the journey and listening to the radio about the Coup updates from Moscow. Lithuanian radio broadcasts were disappearing as the Soviets once again stormed local transmission towers.

She arrived at the Parliament building late in the afternoon and picked her way through a minefield as Soviet tanks approached the city. When the tanks arrived at Parliament close to midnight, everyone waited for the soldiers to fire the first shot before Lithuanians would fire back—using their outdated hunting rifles and Molotov Cocktails. No one was going to leave the building alive before Lithuania was free.

For three days and nights the standoff continued. Sleep deprived, her co-workers and her fielded calls from citizens reporting troop movements and fears, and she kept foreign journalists updated. Finally the hard-line Soviets relented and Gorbachev returned to Moscow. But that didn’t mean the fight was over. Although troops retreated from buildings, those that had been occupied in January, such as the TV tower where the massacre occurred, were still occupied. Only after Lithuania delivered an ultimatum to Moscow did those troops begin their retreat.

She arrived at the TV tower as the Red Army tanks began to withdraw. Thousands of Lithuanian citizens had gathered to witness the event. In a final act of defiance, Lithuanians turned their backs and stood silent as the tanks retreated. She was one of the first to enter the TV tower as she guided a BBC crew in to film the historic occasion.

After 50 years of Soviet occupation –Lithuania was finally, truly, free. Afternoons of “making bullets” with her great-grandmother flooded her memories, and the words of her family through the years filled her heart, “We preserve our heritage because we do not give up hope. Someday, with our own eyes, we’ll see Lithuania free once again.”

Not only did she get to witness history, she was a part of it.

You can check out her web site to get more insight to this remarkable and courageous lady

http://daivavenckus.com/mysite/

On the home page be sure to click “Making Bullets – The Book”

and in the drop down menu click “Making Bullets – Chapter One”

You will be rewarded by being able to read the entire first chapter of her book

I must say that I was quite impressed. Daiva’s writing style not only flows seamlessly but she also has the uncanny ability to make you feel a part of everything going on. I know that this may sound a bit cliché when some one says that a writer has the ability to make you feel like you are there but I can tell you that I DID FEEL LIKE I WAS THERE standing next to Daiva as all the events unfolded and in addition many times I felt like I was Daiva in that she has a way of expressing her emotions and reactions so that you can distinctly feel what she was feeling.

After reading the first chapter I am sure that your next thought will be the same as mine

Where can I get this book???

Well, this is the bad news – You can’t get it

I’m not in the publishing business so I have absolutely no idea as to the logic these people use but I’ll try to put it in a nut shell and then let you figure it out. Daiva has shown her book to a number of publishers in the USA. Their reaction was – THEY LIKED IT!!!

So why don’t they publish it???

Their logic is this, they don’t want to publish a book that will basically be a one shot deal. They want to publish a book that will be followed by other books based on the same theme/topic.

What is even more puzzling and even exasperating is that she offered the book to a number of publishing companies here in Lithuania and they were completely unresponsive. For a Lithuanian company to be unresponsive is unfortunately not uncommon but for the life of me I don’t understand why a Lithuanian publisher would not be interested in a book that can be published in Lithuanian for the home market and in English for the world wide market. There are very few books published here in Lithuania that have the potential be popular in the world wide market and when one is presented to a Lithuanian publisher there is no response – You figure it out???

Dears readers, if any of you are in the publishing industry or if any of you can understand this logic of not publishing a book you think is good because you want to have more books on the same topic to follow it please explain this all to me because this logic totally escapes me??????

Those of you that are familiar with many of the articles I have written for VilNews know that I am adamant in my endeavors to do my (very small) part in telling the world what Soviet Russia did to our country and to our people. It is virtually impossible to find a Lithuanian family that did not lose a loved one as a result of Soviet Russia’s oppression. This is the main aim of Daiva writing this book, she wants more people in the world to be aware of what happened here and it is not just about Lithuania. By making more people in the world aware of the atrocities committed hear it is the hope of people like Daiva and I that this awareness could possibly help to prevent tragic events like this happening again in Lithuania and in other parts of the world. This is why I am so very disappointed and I must say upset over the logic of these publishing houses.

I would really like to read the book. There have been many articles and stories written about the events that took place during this time but to my knowledge there have been no English language books written about these events. The fact that this book is written by a person that can share her first hand experiences with us makes it even more impressive.

By the way, when I said “first hand experiences” I mean first hand experiences. Daiva has been awarded the “Commemorative Medal of January 13” by the Lithuanian Government for her efforts in the struggle for Lithuanian Independence. This medal was awarded to her by the Presidential Decree of President Valdas Adamkus. A book doesn’t get more “first hand” than this.

Lithuanian Presidential Commemorative Medal of Jan 13

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - (2) Comment

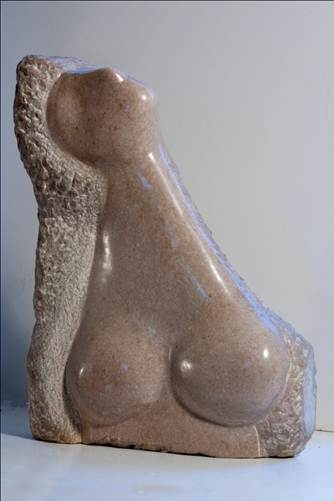

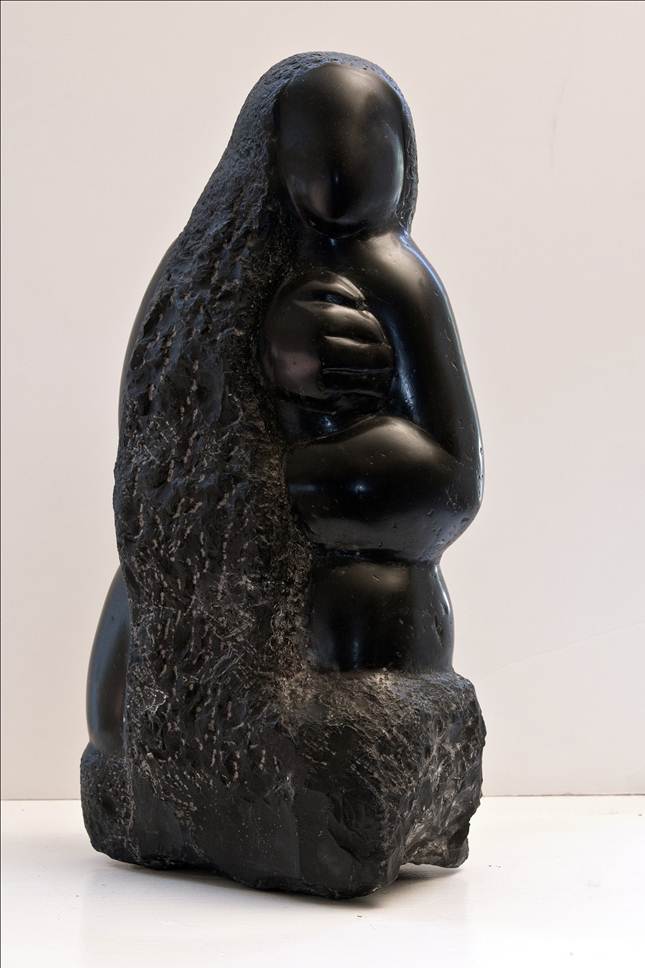

Clara Nathanson

I have a collection of works by Clara Nathanson. I was wondering if you could include them in your web site. Photographed by Brennan O'Brien.

Clara (Nathanson) Sachar was born 1/1/1887 in Lituva, Lithuania, and died 1/23/1968 in St. Louis, MO. She married Charles R. Sachar on 8/18/1914 in St. Louis ...

Patrick Weil Bertrand

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - (1) Comment

Why this perpetual

return to Lithuania?

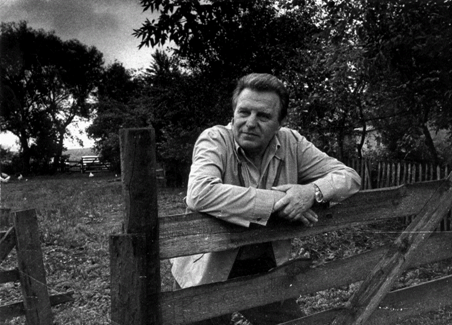

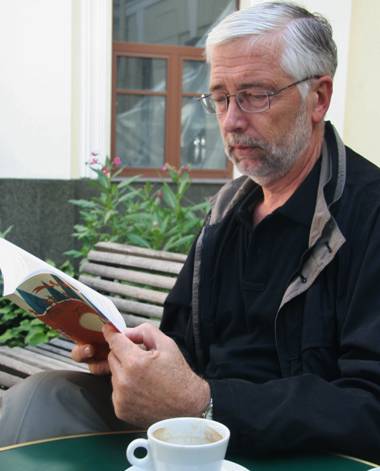

Novelist Antanas Sileika on the Traku - Pylimo street corner

in Vilnius – with his book Underground.

Photo Aage Myhre

Standing on the corner

of Traku and Pylimo

A writer muses about the foreign sources for

his work and what it means to be a Canadian

By Antanas Sileika, novelist

For the fourth year in a row I’m standing at the crossroads of Pylimo and Traku Streets in Vilnius, Lithuania, worrying the place, trying to sift the stories that lie like dust between the cobblestones. I’m slightly sick of this baroque, labyrinthine city - the strangulated cries of the swallows at dusk make me think of the dead souls of forgotten citizens.

Nobody who lives in Vilnius now had great grandparents who lived here - most of the old inhabitants were killed during the war or shipped out after it. Vilnius is old, but the people who inhabit it are relatively new to this city.

They came here after the war, around the time I was born to immigrant parents in Toronto. Although I’ve spent my whole life in Canada, my clan, my people are new to it, and I’m not entirely comfortable in the country of my birth. I keep coming back to this melancholy city of Vilnius, mulling over the past and trying to determine the geography of my belonging.

I’ve never been to Newfoundland or Saskatchewan. I once had fantasies of drinking my way through the Okanagan Valley or of searching out whatever commercial fishermen remain on the great lakes in order to ship out with them. These are oversights I might never remedy, fantasies I’ll never realize.

I’m a fifty-six year-old Canadian, and as much as I would like to write about the place where I live, I keep writing instead about the past and the place my parents came from. I’m slightly embarrassed by this fact, all too aware of then disdain many people hold for historical writing.

Immigrants in the fifties were called “Displaced Persons”, or DP’s for short. I’m undergoing some sort of reverse DP process, being pushed back in time and space. My life has become a time machine, stuck in reverse.

Someone my age should have a clearer view of his place in the world, but the complicated strands of history are getting more and more complicated as I grow older, more tangled.

So why this perpetual return to Lithuania, land of rolling green hills so similar to Southern Ontario? For one thing, the stories here in the old country are so much more brutal, the stakes so much higher than back in Canada. Placed beside the gulag, suburban angst is pitiful. And then there’s the fact that my family history keeps appearing in unexpected places.

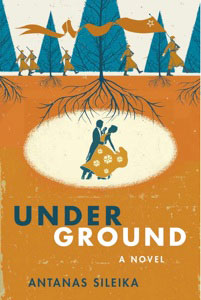

Antanas Sileika's book Underground

I have just come from a meeting with Bernardas Gailius, a young historian who wrote a magazine story about my uncle, Pranas, a man who died in 1952, the year before I was born. My late parents remembered him as the family joker, the must-have guest at any party.

They never did mention that Pranas strangled his lover in 1931, hid her body in a sewer, and hoped to dissolve her remains with acid from a laboratory where he and his cohorts were making a bomb to overthrow the Lithuanian president.

Such a dark story! My uncle was a murderer. Do I carry his blood in my veins?

And there are some oddities to his story - Pranas only got three years for the crime (extenuating circumstances? What could those possibly have been?). Part of his sentence was to support his son by the murdered lover. Somewhere I may have a cousin whose mother was murdered by our common relative. Should I look for this lost cousin? What could I possibly say to him?

To make matters worse, the man pictured in the magazine article photo as “Pranas” seemed to bear an uncanny resemblance to his brother, my father. I stared long and hard at that photo until I realized I was not just seeing family resemblance. I was looking at a photo of my father, not my uncle.

The photograph of the murderer was a photograph of my father.

I’d just met with the historian to ask if my father had actually been the murderer, but the historian said no. There had been an error at the magazine and they had inserted my father’s prison photo by mistake. This new information was both a consolation and a troubling new revelation. On the one hand, my father was not the murderer. That was a relief.

But his prison photo?

It turns out my father had been imprisoned for being part of the same cabal of political malcontents, rebels and potential assassins.

I hadn’t ever heard any of this before.

It made me wonder what else I didn’t know about my deceased parents’ lives. I would have to spend some time in the archives if I wanted to find out because there was no one left with living memory of those events.

But I was in no rush to get to those particular archives. Most people no longer believe that the sins of the fathers are visited on the sons, nor the sins of the uncles visited upon the nephews, but still, one hopes for a little glory in the past, or at least a little righteousness. I felt shaken.

Rather than go back along Pylimo Street to the archives, I could go forward to the Jewish museum.

If my “bad” uncle Pranas had been a shock to find out about, a skeleton whose bones would continue to rattle for a while, I preferred to investigate the past of my other uncle, the one I was named after.

During the Nazi occupation of Lithuania, he had hidden some Jewish boys in his house. This happened during a very bad time because the holocaust was particularly brutal in Lithuania, where so many Jews were killed by Nazis and local collaborators.

At least three of the children my uncle sheltered survived the war. His widow, my aunt, still has a letter of thanks from one of the their fathers. I keep a copy of this letter as a kind of talisman, a good luck charm against the horror of the past.

Danute Selcinskaya, head of the Righteous Gentiles’ Commemoration Department, met me on the top floor of the Vilna Gaon Jewish State Museum, where she kept an office among a dim warren of rooms.

She had a file on my “good” uncle, some scrap of proof that confirmed his actions. If I gave her more information, she could start the process of searching for the saved boys and if they were found, to begin the process to have my uncle named a Righteous Gentile.

Thus if I went one way on Pylimo Street, I could look into the dark past of the first uncle. If I went the other way, I could look into the story of at least one decent person. Is it no wonder these stories attract me? I need to settle some kind of issue of good and evil, if any such settlement is ever possible.

But that isn’t the end of the story, because I am standing at a crossroads. Thus there are two other ways I could go.

If I head up from Traku Street, I will end where I am staying, with relatives of my wife. They are Saulius and Silva Sondeckis, she a cellist trained by Mstislav Rostropovich and he the most prominent chamber music orchestra conductor in the Soviet Union and independent Lithuania.

They are both master storytellers as well, so as we sit and sip tea and eat home-churned butter and white Lithuanian cheese, Saulius has described the darkly comic era of the fifties, especially during the rule of Joseph Stalin, when everyone lived in fear. His stories sometimes have funny or surreal spins to them. For example, the leader of the Lithuanian Communist party stood up after one of Saulius’s concerts featuring the music of Johann Sebastian Bach, turned to the audience and said, “Now that’s what I call Communist music!”

No further explanation was given or asked for, and the approval opened many doors. The chamber orchestra grew in stature in concerts throughout Europe, Asia, and North America. Once, a Moscow concert was held in near-darkness because it was attended by international Communist subversives whose identities had to be kept secret.

I imagine Che Guevara in the dark hall, boning up on culture before heading into the Bolivian jungles to meet his death. And Saulius is there in his tails and baton, leading the orchestra. The frisson of politics and culture is extraordinary, and this story is only one of dozens that Saulius and Silva have told.

These are the sorts of stories that have pulled me back more and more often to Lithuania. The stories compel me, but they unmoor me as well. Canada is the haven my parents found after the war, yet I don’t feel strongly anchored here. If my parents were cast upon a safe shore after the tempest of WW 2, I have sat on the beach my entire life, wondering about their loss. At times, I have set out to sea in my imagination and drifted, living in neither one land nor the other. At times I felt as if I might drift away forever.

But if I have described three routes available to me at the crossroads, each of them into the past, I have not yet described the fourth route, down Traku Street into the heart of old Vilnius. I walk past the ancient mansion of the Tiskevicius family, whose portico roof is held up by a pair of titans in plaster, and I descend into the maze of streets in this uneasy city.

Not far from the dawn gate, where a miraculous painting of the Virgin Mary is adored by pilgrims on their knees, I find a bearded young man with a cigarette between his lips and a sleeve tattoo covering his left arm. He looks a little tired, but otherwise well, this son of mine whom I have not seen for three months, since he deployed out of Val Cartier to fight with the Canadian Army in Afghanistan.

My relief at the sight of him is made acute by the knowledge that he is on leave, only halfway through his tour of duty, which involves carrying a grenade launcher as a corporal in battle group. He laughs a little as I embrace him, and we go into a café to find out how it has been. There we will drink scotch and beer, talk of the ever-present ringing in his ears and a couple of close calls I will not describe to his mother until he returns from his tour of duty. I use the word “until”, but I hover over the word “unless.”

His choice is not one we wanted him to make or even approved of, but we found ourselves impotent in the face of his decision to delay his education at McGill. And so I stood helpless before the face of history that was playing out in front of me, much as it had played out for my uncles, good and bad, and for my hosts in Vilnius, the Sondeckis family.

A new story was unfolding for me now, with stakes just as high as the stakes from the stories in the past. And the effect of this story is to moor me to Canada more firmly than I have ever been moored here before, more strongly than any accident of birth.

If my son should die in battle, he wants his ashes to lie in a military cemetery in Ottawa. Although he lives his life less dramatically, my other son will likely be buried here too when his time comes.

If I have been unsure about my home, unsure of where I belong all these decades long, these two young men are the ones who have pointed out the answer to the question I’ve been asking for most of my life.

It’s not all that unusual, to have my children rather than my parents determine my homeland. It happens to immigrant families all the time. Maybe it just takes a little longer than we ever imagined, just one more generation than we thought.

Late in my life, I have become a fatalist. The currents of history keep on pulling us in various directions regardless of our puny desires. And history isn’t just the past. History is happening right now, for me in a café in Vilnius where my past meets my future in a conversation with a bearded young man in a sleeve tattoo.

(postscript - Originally published in Queen's Quarterly in 2011. Antanas Sileika's son survived the posting in Afghanistan, and has gone on to marry and plans to pursue further studies in Lithuania. The search for records of Antanas Sileika's "good" uncle has run into some hurdles and is ongoing. Antanas himself has had his most recent novel, Underground, translated as "Pogrindis" by Versus Aureus in Lithuania. The novel has been optioned for a film by Donelos Studija. Antanas is doing research for a novel based on the life of Soviet Lithuania's leader, Antanas Snieckus. For all his professed Canadianess, Antanas spends more and more time in Lithuania.

Antanas Sileika is a Canadian novelist and critic.

He was born in Weston, Ontario - the son of Lithuanian-born parents.

After completing an English degree at the University of Toronto, he moved to Paris for two years and there married his wife, Snaige Sileika (née Valiunas), an art student at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts. While in Paris, he studied French, taught English in Versailles, and worked as part of the editorial collective of the expatriate literary journal, Paris Voices, run from the upstairs room of the bookstore, Shakespeare and Company.

Upon his return to Canada in 1979, Antanas began teaching at Humber College and working as a co-editor of the Canadian literary journal, Descant, where he remained until 1988.

After writing for newspapers and magazines, Antanas Sileika published his first novel, Dinner at the End of the World (1994): a speculative story set in the aftermath of global warming.

His second book, a collection of linked short stories, Buying On Time (1997) was nominated for both the City of Toronto Book Award and the Stephen Leacock Award for Humour, and was serialized on CBC Radio's Between the Covers. The book traces the lives of a family of immigrants to a Canadian suburb between the fifties and seventies. Some of these stories were anthologized in Dreaming Home, Canadian Short Stories, and the Penguin Anthology of Canadian Humour.

Antanas Sileika appears occasionally on Canadian television and radio as a free-lance broadcaster.

His third book, Woman in Bronze (2004), compared the seasonal life of a young man in Czarist Lithuania with his subsequent attempts to succeed as a prominent sculptor in Paris in the twenties.

His latest novel, Underground was released by Thomas Allen & Son in spring of 2011. The new novel is a love story set in the underground resistance to the Soviet Union in the late 1940s.

He is the director for the Humber School for Writers in Toronto, Canada, and is a past winner of a National Magazine Award.

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - (1) Comment

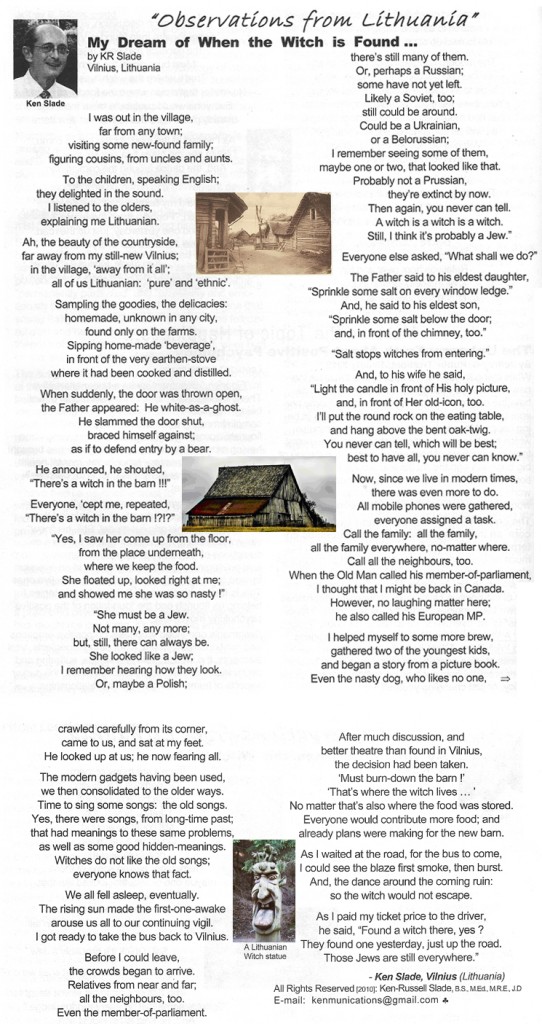

A poem about the witches among us

Lent is imminent, and writer KR Slade wants to remind us of what it

represented in pagan Lithuania. In his poem "My Dream of When the

Witch is Found ..." he deals with today's witches and devils in Lithuania,

the many who are still engaging in anti-Semitism and racism.

By KR Slade

This year, Lent begins on 13 February (i.e., Ash Wednesday). Therefore, 12 February is ‘Shrove Tuesday’:which in Lithuania is called ‘Užgavėnės’ (i.e., “time before lent”) … that is an ancient pagan-festival -- “to chase away winter” -- and: celebrated by fire, and the wearing of masks -- notably representing witches and devils.

Such ancient witches/devils mask-representations, and their symbolism: are more-recently found in the first-half of the 20th century (i.e., in anti-Semitic Nazi, fascist, Soviet, et als. propaganda). Indeed, some people consider such past and current representation(s) to be anti-Semitic.

Moreover, I have found in Lithuania a degree of anti-Semitism that I did not find in the USA LT community; indeed, I find such anti-Semitism here in LT in my own family (here), and with my LT friends, colleagues and associates . . . I find the devil/witch concept still with us, in LT . . .

That is why I wrote this poem; “My dream of when the witch is found.”

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - (0) Comment

|

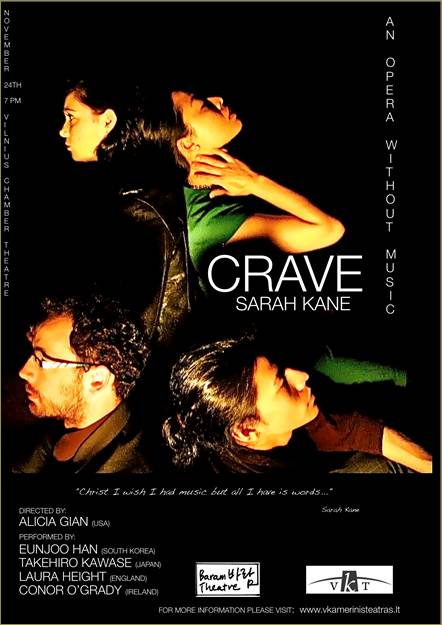

Crave: An opera without music A chamber opera for four voices at Vilnius Chamber Theatre Saturday 24 November at 19:00 |

|

|

November 24, 2012 at 7:00PM the Vilnius Chamber Theatre will present an evening of British contemporary theatre performed by the actors of Baram Theatre Company - an international theatre company based in the UK and directed by VKT’s artistic director Alicia Gian (USA). Gian’s production of Crave, written by British playwright Sarah Kane, has been conceptualized as “An Opera Without Music” and will be showing for one night only in the capital before it begins touring in theatres throughout the UK in January of 2013. The production was developed in the Spring of 2012 in Exeter, UK by Gian and the actors of Baram Theatre Company who have all previously trained in a psychophysical actor training methodology which combines Asian body/mind training practices - yoga, Indian martial arts, and Tai chi to prepare the actor for score-based performances in which actors respond to images that arise from the dramatic material.

Alicia

Gian

“I hate these words that keep me alive, I hate

these words that won’t let me die...”

-Crave

Sarah Kane (1971-1999) was a young, dynamic, and controversial playwright, whose words were immortalized when she committed suicide at the age of 28. During the 1990’s, when drama in the UK was shifting away from the conventions of naturalist theatre, Kane emerged as the quintessential In-Yer-Face British drama playwright, creating provocative dramatic material that required the audience to look up close at issues that generate discomfort. She created an experiential theatre of sensation which challenges the distinctions that define who we are: right/wrong, animal/human, good/evil, art/life, normal/abnormal - binary oppositions that are central to our world view. Her first three plays: Phaedra’s Love, Blasted, and Cleansed were marked by considerable on-stage violence, but her fourth play Crave, written under the pen name Marie Kelvedon (Marie her middle name and Kelvedon the town where she was raised) so that the piece would not be tainted by the playwright’s notorious reputation nor by the fact that she considered the play unfinished at the time of performance (it remained unfinished), was the beginning of her experimentation with a freer, fragmented, and more lyrical form of writing which characterizes the last two and most personal of her plays: Crave and Psychosis 4:48. Kane wrote Crave, which is considered to be one of the more complex plays of the 1990’s, when she had “lost her faith” in love. The themes and images of damaged lives are explored through the fragmented inner journeys of four characters A, B, C and M - four disintegrating minds under the pressures of love, loss and desire.

“I don’t have music, Christ I wish I had music but all I have is words...” - Crave

Gian, the play’s director and a classically trained singer, explains how she structurally approached the fragmented and non-linear text: “Kane offers no setting, no stage directions and no indication of actions in the play and considered it an experiment with the rhythm and musicality of language; therefore we worked with the text as if it were an opera score comprised of arias and oratorios - a chamber opera for four voices. Sections of the text were divided according to recurring themes and motifs, but instead of singing with the voice, the actors “sung” with their bodies by developing movement scores activated by images that arose organically from the text and developed in rehearsal. The actors trained in operatic breathing techniques for four weeks before any staging of the text began. The goal was to learn to breathe together and allow the breath - just as it does in singing - to sculpt the shape of the thought through movement and text.”

“I keep coming back...again and again...the eternal return...” - Crave

Crave is considered to be Kane’s most personal text and also an ambitious attempt at recasting theatrical form. It is permeated with allusions from the Bible as well as Shakespeare and T.S. Elliot’s “The Wasteland”, but Gian and the actors of Baram primarily explored the text through the Buddhist concept of Tanhā - translated as a craving or thirst and is comprised of three essential stages: the desire of having, the desire of becoming, and the desire of escaping. “As we studied the text we identified each character’s fluxuations between these three stages of desire as described in Buddhist philosophy. This allowed the actors to chart the course of their character’s spiritual journey amongst the fragmented and harsh terrain of the text.”

Gian and Baram Theatre are currently staging Sarah Kane’s other one act play, Psychosis 4:48, which is planned to premiere alongside Crave in the Summer of 2013 in the UK.

Tickets are available through Bilietai.lt and at the door.

Doors open at 6:30 to the public

After the show the audience is invited to stay for a glass of wine to meet the actors and discuss the performance.

Vilnius Chamber Theatre is located at 23 Konstitucijos Prospect - directly across the street from the National Art Gallery.

For more information please visit: www.vkamerinisteatras.lt

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

Let's introduce you to Antanas Šabaniauskas (1903–1987), considered to be the most sought-after artist of the little stage in interwar Lithuania. His intensive professional career lasted for six decades. Huge number of copies of his records was circulating throughout Lithuania. Šabaniauskas sang with Moishe Hofmekler’s orchestra and Alfonsas Mikulskis’ vocal male octet. He took part in musical programmes in Metropolis and Versalis restaurants, sang in the State Theatre Opera choir, appeared in minor tenor roles. His voice was also heard in radio broadcasts as well as in concerts around Lithuania. His success inspired Lithuanian composers Kajetonas Leipus, Emerikas and Stasys Gailevičiai, Juozas Bankas, N. Naikauskas, Juozas Pakalnis, Jurgis Karnavičius, Leonardas Lechavičius and Pranas Juodka to compose for the little stage. Šabaniauskas performed foreign schlagers almost exclusively in Lithuanian. He recorded 64 works (32 LPs) in London (Columbia) and Copenhagen (His Master’s Voice).

To read and listen more, go to

http://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLE91DEB0ECDE727FB

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

VilNews e-magazine is published in Vilnius, Lithuania. Editor-in-Chief: Mr. Aage Myhre. Inquires to the editors: editor@VilNews.com.

Code of Ethics: See Section 2 – about VilNews. VilNews is not responsible for content on external links/web pages.

HOW TO ADVERTISE IN VILNEWS.

All content is copyrighted © 2011. UAB ‘VilNews’.

Click on the buttons to open and read each of VilNews' 18 sub-sections

Click on the buttons to open and read each of VilNews' 18 sub-sections

.jpg)