THE VOICE OF INTERNATIONAL LITHUANIA

|

VilNews has its own Google archive! Type a word in the above search box to find any article.

You can also follow us on Facebook. We have two different pages. Click to open and join.

|

Culture & events

- Posted by - (8) Comment

Oh, those old Lithuanian

wedding traditions

The article author, Kestutis Eidukonis, with the bride and her maids.

Marriage and death - these are the events to which ancient Lithuanian culture gave special attention to, and judging by the surviving customs and folklore, the most significant of these was the wedding, for it was on the family that the entire community depended on for survival, structure, and stability - not only of the community but of the whole nation. It is therefore understandable why the creation of a family - a wedding- receives so much attention in both ancient and present day Lithuanian culture.

One only needs to walk around old town Vilnius or Kaunas or any good size Lithuanian town on any given weekend to see wedding entourages accompanied by photographers posing for pictures at churches, bridges or any other landmark. These festivities occur everywhere in Lithuania. It is a wonderful sight for a country. It is usually a sign of confidence and hope in the future. Of course, traditions change and some people are reluctant to celebrate the wedding using some of these traditions but it was interesting to see them none the less and hope people continue to observe them.

I recently had the privilege of attending one of these special occasions in Žemaitiją in the wonderful towns of Veiverženai, and Švekšna I was invited to the wedding of Arturas and Žavinta, (her name means Enchanting) and I want to thank them and their families for sharing this beautiful experience with the me and the readers of VilNews.

At Žavinta's and Arturas's wedding, all the old traditions of a Lithuanian wedding came into play. All the actors, the matchmaker and his wife, the groom, the bride, the parents, bridesmaids, groomsmen, musician, large number of relatives and friends and most importantly, the children, had a part to play.

The day started at the bride's house with the bride getting dressed for the occasion being assisted by the brides maids. As the magic hour got close, the groom together with groomsmen arrived at the house, where, family and friends waited. The ceremonies began with the Matchmaker and Mrs Matchmaker (The matchmaker's wife) taking charge. The groomsmen are introduced to the bridesmaids. The boys tied flowers on the bridesmaids wrists and the girls in turn put a flower on the lapel of the boys. The future bride and groom in turn present a typical handwoven Lithuanian sash to the Matchmaker with the words Matchmaker - Liar.

The next part of the festivities was both comical and melancholic. The parents shared with everyone present their fondest memories of their children. Their first words, the lullabies they used to put them to sleep with and anything else memorable. The groom's mother then pinned a flower on her son's lapel, and in traditional Catholic families the couple is presented with a rosary as symbol of God's blessing. The bride and groom then bid farewell to their parents by kissing their hands. Tears flow copiously! Moms are usually very tearful - not so the fathers. Guests applaud and cry!

After this the couple proceed to the church where the mass is said and the couple exchange vows - pretty much like any other wedding ceremony. The couple also adopted the custom of releasing white turtle doves after the wedding ceremony outside the church.

After the church ceremonies the young couple along with their whole entourage hop into their cars and go on a noisy, horn blasting, few hour long trip. Photos are taken and rituals are performed. These combine a few old and new traditions - the old tradition consists of sorting through a bunch of stones labeled by the maid of honor with good and bad characteristics of the couple. Love jealousy, respect, hot temper, etc. The good stones are kept and put in a basket. The bad ones are tossed away. The stones have a special pagan significance - in old times they were considered messages to the gods. The newer tradition consists of locking two hearts together with a symbolic lock. The lock is often placed on a bridge and the key is discarded. Most Lithuanian bridges are covered with such locks. (I have also seen people removing their locks after a divorce or separation). The wedding party also uses this occasion to go visit close relatives who are ill or frail and could not make it to the festivities. The groom is also supposed to carry the bride across any and every bridge they come to.

Finally, according to old traditions it is time to go back to the house where the parents and the guests are eagerly awaiting. Weddings used to take place in one of parents' home. Now days, the celebrations are often held in a hall or in a place specially selected for its rural scenery or for the occasion. However, the decorations, like in the old days remain the same, the yard is decorated with birch branches flowers and other decorations. Our wedding took place in Alsė, a "kaimo sodyba" - a rural B & B.

After raising Cain on the roads and streets, the newly weds return to the hall where they are welcomed by their parents with the traditional gifts of bread and salt and water. (The bread symbolizes life, salt bitter moments and the water or wine to wash everything down) But before they are allowed to enter, they are required to undergo a variety of challenges. What would Lithuanian wedding be without jokes, and pranks? The organizer of all this is the irreplaceable wedding musician and the matchmakers who, up until the return of the young couple have been busy preparing for the first trials, an obstacle course for the groom to navigate while carrying his bride blindfolded - she is supposed to coach him where to walk. A baby doll for the bride to wash and diaper. Firewood for the groom to chop, a dish has to be broken and it will predict the number of children they will have, the bride will have to demonstrate that she knows how to peel potatoes. All this is accompanied with cat calls from the audience and commentary from the matchmakers as to how well or how ineptly the newly weds are performing their tasks. Upon completion of their tasks the newly weds request permission to enter the hall, but before the couple are allowed in they must get the approval of all the guests - who might want to challenge the couple. The maid of honor comes to the aid of the couple with a basket of candy and goodies to bribe the guests with. Many of the traditional matchmaker tasks have survived to this day but some are modified to fit the times. It is the matchmakers jobs to keep the evening flowing with toasts, songs, games and speeches. Everyone present is offered a chance to talk. The speeches have to be witty or sentimental, and they are always heartily applauded. The food was plentiful and delicious. Each table had official "bottle masters" and "happy attitude enforcers" assigned. The staff of the "Alsė" was great - pitchers were always full and platters of food just kept on coming. The place where the wedding took place was just outside the town of Švekšna it is a "Kaimo Turismo Sodyba" - a rural village garden type of an accommodation - with gazebos and other areas where guests young and old could socialize and imbibe. It also had places where everyone could rest, either in private rooms or communal bunk type accommodations. People with less stamina, were given semi-private accommodations - while the younger folks were provided with communal sleeping arrangements.

Around midnight - everyone was invited to a fire (normally a fireplace ) but in our case it was burning candles where everyone was asked to sprinkle amber dust on the flames and make a wish for the newly weds. Why Amber? Amber is considered to be the oldest, healing, spiritual rock with a large amount of organic energy. This magnetic stone, can still be found in the Baltic Sea, it is used for attracting love, carrying for and protecting happiness. It is symbolical invitation to an old Lithuanian ancestral spirit, to care for our young family and for our ancestors to reinforce the strength of the spirit of the family hearth fire. This magical fire now resides in Arturas and Zavinta and burns passionately within them.

The party continued till seven AM - With guests disappearing little by little till only the most energetic and hearty ones were left.

On the second day of the wedding - we were awakened by our colorful musician wearing a long wig. knocking on our door and insisting on us opening the door whilst he and his accordion serenaded us with his "wake up" song. Good natured threats were hurtled back and forth. Dire consequences were predicted for those who did not open up and wake up. Little by little, everyone woke up and gathered around for a breakfast of sour kraut soup served with potatoes and Kastynis ( A rich mix of butter and cream). This traditional hangover remedy , a visit to the sauna followed by a dip in the pond quickly revived everyone. The sauna and the dip in the pond was voluntary - though many took advantage of it.

Around noon - everyone was ready to start partying all over again. Everyone gathered at the banquet hall for second round of revelry. In the meantime, the bridal party decided that the matchmaker exaggerated the grooms qualities when he recommended the groom to the bride and her parents and that for being such a big liar, he needs to be strung up. The matchmaker at first tries to make excuses, but then when he sees that it is doing no good he starts to read his humorous last testament. This leaves everyone in stitches! The Matchmaker is than saved from hanging by the young bride - who ties her sash on him as a sign of respect and as sign of thanks for finding her a great husband. The wedding party goes along with the bride and decides that the matchmaker wasn't a liar, after all. He did match up these two wonderful young people and his services are still needed for the remaining large group of unmarried women. The matchmaker is allowed to live but now has to wear his matchmaker's sash around his neck as a reminder of the perils of his job.

Of course, there was still a lot of celebrating to do, games, dances and songs. The wedding went on till later that evening. But most importantly the Lithuanian Spirit was alive and well there. Happy guests, happy newly weds and most important of all - happy young eyes were watching all of this, for you see the young children were a part of this the whole time: This to them was a Fun Lithuanian Wedding!

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - (1) Comment

A new film, Land Of Songs, will show the Lithunian dainos (songs) as living, breathing stories, deeply rooted in their natural surroundings, daily routines, and rich histories.

Močiutės dainos

Land of Songs Director Aldona Watts with the močiutės: Stasė Bogušienė,

Jonė Dvareckienė, Marytė Klimavičienė, and Pranė Barysienė.

Hello and Sveiki!

My name is Aldona. I’m a Lithuanian-American multimedia producer from San Francisco, living and working in Brooklyn. This project has been a dream of mine for so long now that I’m thrilled to finally make it happen!

It all began seven years ago. My family and I visited Lithuanian friends in the village of Puvočiai, and they invited their neighbors, the močiutės (or "little grandmas"), over to sing for us. These močiutės, they told us, were the last generation in a long line of traditional folk singers with ancient roots.

At twilight we laid tables under the trees with food and drink. I barely noticed the faint sound of voices weaving through the forest, until they mounted to a loud front of song. And then I saw them: a small herd of hunched figures making their way towards us, their white headscarves bobbing through the trees.

The songs were at once melancholy and joyful; the hauntingly beautiful harmonies seemed from another world. After each song, the women’s wrinkled faces cracked into wide smiles, and the ghostly echo of the voices ringing through the trees was replaced by raucous cackling.

When it was time to say goodbye, the močiutės left as they came, singing all the way. Long after they disappeared, their voices remained.

At the time, my own beloved grandmother had recently passed away. She had been a master storyteller, and I was raised on her tales of survival as a teen fleeing war-torn Lithuania. My pain at losing her was compounded by the realization that I had also lost her stories. I felt I hadn’t done enough to carry on the oral tradition of my own family, and I wished that I had recorded her, when I had the chance.

So when I saw the močiutės sing that night, I resolved to one day make a feature documentary film about them. After seven years, and with a little help, I will finally be able to do this.

The Land Of Songs

Puvočiai is nestled deep in the forests of a region called Dainava or “The Land of Songs,” known for its rich tradition of folk singing called the daina. Ranging from the deeply personal to the profoundly political, the many-layered dainos are woven with the memories of the souls who have lived and died in these same forests for millennia.

Remnants of the ancient pagan past remain intact in many of the dainos, and great pains were taken to preserve them throughout modern history, even as Lithuania was pummelled by wave upon wave of war and occupation. Today, many of the younger generations are leaving the villages to seek work in the cities and abroad. In Puvočiai, for the first time in history, there is no one to carry on the oral tradition of the daina.

The Močiutės

Stasė Bogušienė (b. 1935), is an outspoken and vivacious ringleader.

Marytė Klimavičienė (b. 1942) has a tough demeanor and a great wit.

Pranė Barysienė (b. 1929) is soft-spoken with a sweet nature.

Jonė (“Jonukė”) Dvareckienė (b. 1931), the tiniest of the bunch, is nonetheless the strongest voice and often leads the others in song.

Marytė Bingelienė (b. 1931) has missed recent performances and gatherings due to serious health problems.

These five women are the last living members of a group that once numbered twelve friends and family. They started singing as girls, to lighten their load while mushroom-hunting in the forests. They sang at festivities, and they sang to remember the stories of their mothers and grandmothers. Perhaps most importantly, their “siren songs” perked the ears of young men in neighboring villages. When war and repeated occupations left half the village burned to the ground, the women sang to rally their strength and ease their pain. An entire history of a nation in turmoil is chronicled in their dainos.

The Film

The objective of this film is not only to preserve the precious dainos of the močiutės - transcriptions and recordings can be found in archives throughout the country. Land Of Songs will be unique in that it will show the dainos as living, breathing stories, deeply rooted in their natural surroundings, daily routines, and rich histories. Shot in an observational style, Land Of Songs will be multilayered and poetic, like the dainos themselves.

We plan to shoot next month and finish the film this fall.

Director / Producer / Cinematographer: Aldona Watts

Local Producers: Kęstutis Nėnius, Danguolė Nėniuvienė, Ingrida Nėniuvienė, Motiejus Nėnius

Producer / Production Sound Mixer: Julian Watts

Producer: Matthew Shorr

Local Production Coordinator: Algimantas Kazlauskas

Sound Design: Aldona Watts in collaboration with Kyle Keays Hagerman

Land Of Songs is a true labor of love, and its success relies on friends, collaborators, and community members who are willing to help out in any way they can. I am keeping the budget as tight as possible, but I know that the story I have to tell is priceless. I also know that it has to be told now, before it’s too late.

How Kickstarter works: You can make a commitment to contribute, and you will not be charged until the deadline. If the goal is not met by the deadline, you will not be charged at all. It’s all or nothing.

Any and all funds raised will go towards production costs: video and audio equipment, travel expenses, compensating the local crew, Kickstarter fees, and Amazon processing fees.

You can also help by simply spreading the word about Land Of Songs!

www.facebook.com/landofsongs

www.twitter.com/landofsongs

www.landofsongs.com

Please contact me with any questions you may have.

Thank you and labai ačiū.

Aldona

About Aldona Watts:

Aldona Watts is a multimedia producer living in Brooklyn, New York. She graduated from New York University, and has since produced several audio documentaries. She currently manages and produces GRYC Radio, a youth radio station in Queens, and is the host/producer/engineer/DJ of a long-running weekly radio show broadcasting in New York City

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - (1) Comment

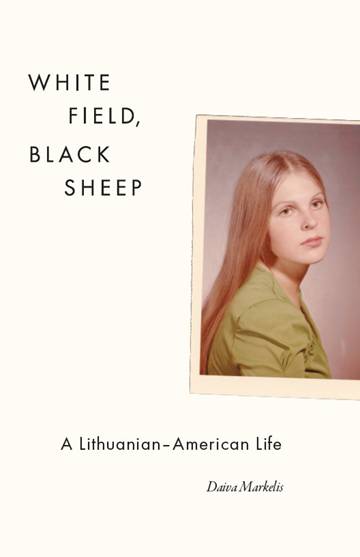

By the end of the book, author Daiva Markelis discovers

Her own way to be both

Lithuanian and American.

Daiva Markelis interviewed by Ellen Cassedy

Daiva Markelis's memoir, White Field, Black Sheep: A Lithuanian-American Life (University of Chicago Press, 2010), tells the story of her growing up as the daughter of postwar Lithuanian immigrants in the 1960's and '70's near Chicago.

The book alternates between the story of Markelis's youth – especially her struggle for cultural identity – and a series of touching later scenes with her octogenarian mother.

We see Daiva and her sister begging for real American Halloween costumes and a plastic Christmas tree, while the parents insist on speaking Lithuanian and holding true to their traditions. The descriptions of Catholic school, Lithuanian scout camp, and the family resort owned by Valdas Adamkus (who later returned to Lithuania and became its president) are tart and funny.

Markelis reveals a culture as well as a personal history. She writes affectionately about the streets, the buildings, even the tackiest billboards of her home town - while, at the same time, not shrinking from frank portrayals of racial tension and alcohol abuse. The portraits of her parents are filled with a lovely tenderness, even as she pokes fun and reveals some of their failings.

This tale of seeking cultural identity within an immigrant community comes to an uplifting conclusion. By the end of the book, Markelis has discovered her own way to be both Lithuanian and American.

Daiva, the title of your book comes from a riddle that your father posed to you when you were a child:

Black sheep on a white field;

He who knows them, leads them.

The answer is "letters on a page." You are truly a "shepherd of words" – an eloquent, elegant writer. Your love of both languages shines throughout your memoir.

Thanks for the kind words, Ellen. I'm going to start listing "shepherd" as my occupation!

I've always thought being bilingual is an advantage in so many ways. Growing up in a heavily Lithuanian culture and speaking Lithuanian as my first language have given me a different lens through which to observe American life. This has enriched me as a writer and as a human being.

My parents encouraged reading, both in Lithuanian and in English, and that has probably had the biggest impact in my wanting to be a writer and a teacher of literature.

A particularly touching part of the book, for me, was the brief section called "The Alphabet of Silence." You describe how, near the end of your mother's life, she presented you with a set of silverware that had been given to her family for safekeeping by a Jewish doctor, who then perished in the Holocaust.

You challenge your mother, asking why the fate of Lithuania's Jews was not mentioned in the community when you were growing up. On the verge of tears, she asks you to reassure her that she was a good mother.

Your handling of this scene is so subtle and beautiful that I'm reluctant to ask you to say more. But can you? Is such a conversation between mother and daughter a common one in Lithuanian-American homes?

I'm so glad you liked this section, Ellen. I wanted to write more about the many silences I experienced growing up in a Lithuanian household, but I wasn't sure how to go about this. I didn't want to alienate Lithuanian readers, many of whom are still reluctant to discuss what happened during the Nazi occupation of Lithuania. In retrospect I think I was being too subtle.

I was very close to my mother. We had many interesting conversations about a variety of topics – religion, politics, even sex. I think many Lithuanian-American daughters are close to their mothers – sometimes I think our mothers felt a bit lonely and misunderstood, and thus turned to their daughters for companionship. Of course, I thought my mother was special. She was a very outspoken, funny, and intelligent woman.

How has the book been received within the Lithuanian-American community? How do you respond to people who worry that you've shown too much dirty Lithuanian-American laundry in public?

I've received many letters, emails, and phone calls from Lithuanian-Americans saying how much they loved the book. I really wasn't expecting that! The most positive responses have come from individuals my age who grew up in Chicago or Cicero, thanking me for writing a memoir that chronicles experiences they've gone through with parental expectations, Lithuanian Saturday School, and even drinking at the bars on 69th Street in Marquette Park.

Lithuanian-Americans from an earlier generation--those whose grandparents immigrated to this country at the turn of the last century--also seem to like the book. Friends tell me that some Lithuanians are angry that I emphasize drinking so much. But I wrote what I observed and lived through, and drinking was a part of that. As I grow older I care less about what people think--I tell my students that a growing indifference to the judgments of others is one of the advantages of aging.

Also, the idea of "dirty laundry" is, to some extent, subjective. I'm sure that some Lithuanians feel I've revealed too much. Yet one friend said that I held myself back too much. And non-Lithuanian friends and critics who've read my book have remarked on how strongly the emphasis on education and culture in Lithuanian life comes through.

Books about the Lithuanian-American experience are few and far between. Why do you think this is?

There aren't that many of us out there, at least compared to the Poles, who've written much more widely about their experiences as immigrants and children of immigrants. Also, Lithuanian-Americans of my parents' generation encouraged their children to go into practical fields such as engineering and nursing. Perhaps surprisingly – because there are fewer of them – Lithuanian-Canadians have led the literary way. Antanas Sileika's first novel, Buying on Time, is a wonderful and very funny book about growing up Lithuanian-Canadian. And Irene Guilford's The Embrace examines the complex relationships between Lithuanians in the homeland and the diaspora. Both authors have influenced my own writing.

|

|

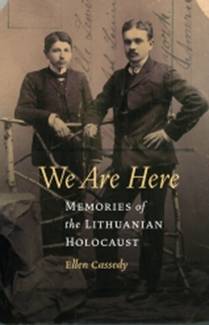

ELLEN CASSEDY Ellen Cassedy traces her Jewish family roots to Rokiskis and Siauliai. Her new book, We Are Here: Memories of the Lithuanian Holocaust, was published in March and will appear in Lithuanian soon. She lives in Washington, D.C. Visit her website at www.ellencassedy.com.

|

|

|

DAIVA MARKELIS Born in 1957 in Chicago to Lithuanian immigrant parents and raised in Cicero, Daiva Markelis has found unexpected contentment amidst the cornfields of Central Illinois. She is an associate professor of English at Eastern Illinois University, where she teaches creative writing, composition and rhetoric, women’s memoir, and myth and culture. She is a cofounder of Past/Forward, a memoir-writing group open to the public that meets twice a month and consists of ordinary people, many of them retired, writing moving, insightful, often humorous life stories. |

|

Daiva received her doctorate from the University of Illinois at Chicago in Language, Literacy, and Rhetoric. Her dissertation deals with the literacy habits and oral traditions of Lithuanian immigrants; chapters have been published in the journals Written Communication and Lituanus, and in the edited volumes Ethnolinguistic Chicago and Letters across Borders: The Epistolary Practices of International Migrants. Daiva has presented her research at the Modern Language Association, the Conference on College Composition and Communication, the Association for the Advancement of Baltic Studies, and the National Council of Teachers of English. She has also written several academic papers in her native Lithuanian.

Her master’s degree is in English with a specialization in creative writing, also from the University of Illinois at Chicago. Daiva’s short stories have been published in Cream City Review and Other Voices. Her creative nonfiction has appeared in The Chicago Tribune Sunday Magazine, The Chicago Reader, Crab Orchard Review, Writing on the Edge, Women and Language, Mattoid, Agora, and Fourth River. Mongrel Tongue was a finalist in the 2007 Arts and Letters competition in creative nonfiction. The Lithuanian Dictionary of Depression was a runner-up in the 2009 American Literary Review creative nonfiction contest. The Review published the essay in its Spring 2010 issue.

Daiva cheers for the White Sox. She loves to knit, scrap-book, read, and listen to music, everything from Bach, Beethoven, and Brahms to bebop, bluegrass, Brel, the Band, and the Black Eyed Peas. Her favorite color is red, her spirit animal is a polar bear, her astrological sign is Capricorn. She wants a puppy for Christmas.

|

|

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - (0) Comment

Letter from our VilNews’ Washington correspondent:

It was a pleasure meeting readers, librarians, booksellers, bloggers, and publishers’ reps at BookExpo America in New York City last week. I was honored to be among the 700+ authors signing books at the largest book trade gathering in the U.S. Here I am with Donna Shear, director of the University of Nebraska Press, my wonderful publisher.

A special treat was seeing Susan Nussbaum accept the Bellwether Prize for social engaged fiction from Barbara Kingsolver. Another highlight was visiting the Read Russia booth to chat about a possible Russian translation of We Are Here. And then there was the once-in-a-lifetime chance to pose with Olivia the Pig.

For more details, visit my website. Mark your calendar – we’d love to see you there!

Praise for We Are Here

“Pioneering… will reach out to Jews, Lithuanians, and all those who care about not replaying in this new century the disasters of the century that has just ended"

Michael Steinlauf

“…deeply moving…her book offers a unique perspective…complex human texture, rooted in an oft-forgotten Yiddish cultural context, a tapestry of events which elsewhere too often appear as one-dimensional. Readers will doubtless be immensely enriched by her experience.”

Dr. Saulius Suziedelis

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - (0) Comment

Ars longa, vita brevis

Art is long, Life is short.

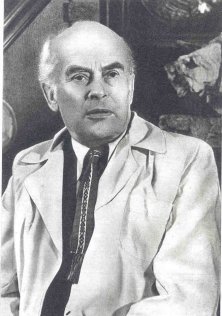

Professor of Creative Writing and American Short Story at Concordia University, Canada,

the founder and main organizer of the SLS, and author Mikhail Iossel.

Photo: Kestutis Pleita

Professor Mikhail Iossel interviewed by Eglė Kačkutė

This summer, July 15-28 and August 29-12, the 14th edition of Summer Literary Festivals known as the SLS will be held in Vilnius for the 3rd time running. Literary workshops will be conducted by experienced and well known North American writers; famous photographers, artists and researchers will be taking part in the program. SLS is the biggest independent creative writing program in the world that brings together an impressive number of talented teachers and writers to be. The creative writing phenomenon is rife in Europe, too. The first British Creative Writing course graduate in the UK is legendary Ian McEwan who continues to reap the plentiful fruit of his studies at East Anglia University thirty odd years ago. Creative studies are known to be more that just a means to get better at writing, they also serve as an initiation into complex and competitive world of publishing, providing writers to be with much needed references.

Eglė Kačkutė is talking to professor of Creative Writing and American Short Story at Concordia University, Canada, the founder and main organizer of the SLS, and author Mikhail Iossel.

This year for the fourteenth time running, you’ll be organizing the biggest international creative writing program featuring North American and Canadian writers. You teach creative writing at Concordia University and are a writer yourself. What’s your story? How did you come to writing in English and especially teaching writing in English?

I came to the US in 1986, after five years of having my application for émigré visa turned down by the competent organs. Back in Leningrad, which is where I was born and raised, I was trained and for a few years worked (poorly and lackadaisically) as an electrical engineer, in the employ of the research institute charged with the task of lowering the electromagnetic fields radiated in the ocean by the outmoded Soviet submarines, so as to make the latter less detectable by the enemy radars (it was a hopeless enterprise, of course); and I also – especially since the beginning of the 80s -- was active in the city’s burgeoning underground (“samizdat”) literary community.

(Once I had become a “refusenik,” however, my line of occupation had changed quite drastically, and for the last couple of years of my “Soviet” life I worked as an alternate night-guard at Leningrad’s Central Park of Culture and Leisure, tasked with the responsibility of keeping an eye on the city’s only roller-coaster. I loved that job.)

My original “Plan-A” idea, before arriving in America, had been to make a living in the new world by continuing to write in Russian; and when, within the first day or two of my post-Soviet life, it was explained to me how and why that wouldn’t work, I found myself at a loss as to what to do next, for I had no Plan B. One thing I did know for certain, though: I didn’t want to be an engineer again – and in general, I had resolved for myself never to try and make a living by doing anything that, to me, felt like a waste of life.

I could read English well enough, at that point – back in Leningrad, I had translated some contemporary American prose and poetry for “samizdat” journals, including the one I co-published myself – and my spoken English was rather passable; but my oral comprehension, in the absence of any prior practice, was pretty abysmal, not to mention my ability to write in English, which was non-existent, for all intents and purposes.

In an effort to improve the quality of my English quickly – and because the idea of being surrounded by books was soothing and appealing to me, in my discombobulated state just then – I undertook a string of part-time jobs with some terrific bookstores: first around the Harvard Square and other parts of larger-Boston area – and then in Northern California, where my relatives on my father’s side lived.

Unfortunately, I was unable to keep any of those jobs for long. I was, at that point -- not atypically for many Soviet émigrés in those days (when one left the country, and one’s friends and family, forever, in the firm knowledge he would never be able to go back and see them again) -- in a fairly sorry state of mind and spirit: confused, depressed; in a word, sick. I had no clear personal strategy for survival. It was purely a day-by-day kind of existence.

I watched television for hours on end, cooped up in my tiny, overheated sixth-floor, rooftop room on the outskirts of Boston, in a large rambling walk-up apartment owned by a Russian émigré, where seven or eight other people (mostly, from Columbia, for some reason) lived; but my old, rabbit-ears TV, which I’d found on sitting on the sidewalk one day, only allowed me to watch one channel -- and it was the Boston Celtics, basketball channel. So I was mainly learning the basketball-related part of the language.

At some point during those months, in order to distract myself from the sheer uncertainty and sadness of my circumstances, sleepless and homebound and unemployable, I started trying to write sentences in English. Not stories, at that point, just yet – just the competent, authentic-looking sentences. It was, at first, a purely mechanical, self-therapeutic exercise: putting together the small blocks of short, direct sentences, one after another. It was indeed a comforting exercise for me: I was overwhelmed with nostalgia, you see, and my native language, Russian, would not allow me to write about my life objectively and dispassionately, with any degree of calm remove, for it was as natural to me as the very air I breathed and therefore offered no resistance in the process of writing; and as soon as I started writing in Russian, I immediately succumbed to sadness and depression and commenced to wallow in misery and self-pity. The very foreignness of a foreign language – English – afforded me the distance I needed to put between myself and my own life, my present circumstances and my memories. A foreign language one knows well enough to know he doesn’t know it well serve as a natur4al obstacle every writer needs to come up with for the purposes of his or her writing. I could not wax emotional in English, could not feel sorry for myself, could not write soulfully and beautifully about my nostalgia, about the friends I would never see again. I could do nothing but be adequate to the words I was trying to put on paper. English, then, served as a sort of Plexiglas wall standing between myself and my past, my very life. I only could be adequate, as I said, to any English sentence at hand.

One sentence, then another one, and another and soon enough, you have a paragraph. Then another paragraph, and then another. Every sentence had to make direct narrative sense, and every single paragraph had to work towards the telling of the story under writing. It was like walking a narrow path through the swampland: you don’t want to deviate from it at any point, or else you’ll get bogged down without a trace.

Incidentally, and a propos of what I am describing right now: when Samuel Beckett – perhaps the most linguistically gifted and prodigiously verbose (in his youth) writer in all of the 20th-century literature, was asked why, at the age of 46, he switched to writing in French (a language he was not perfect in)< he replied: “I know too many words in English.”

So it went. By that point – early 1987 – a friend at one of those bookstores I’d worked at had told me about the phenomenon of graduate creative writing programs in the US: you could apply there and, if accepted, you would get two year’s worth of time unobstructed by any other practical worries and considerations; they’d give you a place to live, if they liked your writing, and they might even waive your tuition, or you could apply for a student loan. All you had to do there was write.

So I applied to one of those programs – at the University of New Hampshire – and I was subsequently accepted, even despite the fact that I had not a single story in English finished by that time.

The rest was more or less clear sailing: I kept on writing in English, gradually getting better at it (as you get better at anything you do stubbornly and consistently and with passion); and eventually, one story got accepted for publication in a literary journal, and then another – and I was on my way, by and large.

Within a few months, an editor with a large publishing house had contacted me and asked if I might have enough stories for a collection, so I told her I’d have the needed number of stories by the time she needed them.¨

In due time, the book of my stories got published, I went to Stanford University on a post-graduate writing fellowship (the Wallace Stegner Fellowship); then I applied for a teaching job at the University of Minnesota, where there was an opening; I was hired by it for a two-year stint. Then I was lucky enough to have been awarded the prestigious Guggenheim fellowship in writing, which indeed is a coveted distinction to get, and one that makes getting jobs easier. I subsequently went on to teach at a number of colleges and universities, in the graduate and undergraduate writing programs (New York University, St. Lawrence University, Union College), before settling permanently in Montreal, which is home now.

That’s the whole story, in a nutshell.

As an émigré and especially as a native Russian language speaker writing in English you probably have to do a lot of cultural translation and adapting from one culture to another. How do you go about it? How do you feel about it?

I don’t think I do much of any such translation anymore, be it in the metaphoric or literal sense. (This, quite apart from the fact that the two languages are not compatible enough structurally to lend themselves easily to the process of instantaneous translation by the translation engine of one’s mind. To me, the oft-asked question, “What language do you think in?” – doesn’t really make much sense, since I don’t really think in words, as most people do not, either. The language of thought is separate from the language of words, thought made word.) I believe -- which is to say, I feel – I have found a place of balance for myself -- or rather, the process of my life itself has found such a place of psychological and intellectual balance for me.

I may, fancifully speaking, be suspended between two worlds, the old and the new one: the world of my past and that of my present, with one foot planted in the present and one in the past; and the past, of course, is also the present.

I feel that my first several years in the new world, which were quite hard and difficult, filled with doubt and nostalgia and despair – those were the years when this process of dividing myself into two selves was taking place. Which, basically, may be a way of me saying that there are two people cohabitating inside me: one belonging in the world of Russia, the other -- citizen of the larger, broader world.

I am very plugged in to the current developments in Russia, I follow them closely, I spend quite a bit of time every day on the Russian websites, I read the new literary publications in Russia, I speak to some very close friends from Russia, both living there and abroad; I still feel that Russia is home for me, in some esoteric way: and when I’m back in Russia, I understand the code of people’s living there, I feel that I belong there – although I no longer live and could never live there again. But my life’s center of gravity has long shifted towards the broader, larger world of my post-Soviet existence, my home is the world outside Russia. I am a citizen of the US and a permanent resident of Canada, but I feel that I live in a larger world than just that of North America.

That having been said, I am a professor of English who teaches the university-level creative writing and American short story; I read lots of contemporary American literature (albeit not as much as I would like perhaps), as well as my students and other young writers’ stories – hundreds of stories every year. Somehow, I manage to stay in one piece and not feel torn or conflicted within my own head and my own heart – but, again, this did not happen quickly or easily; as nothing really good ever happens in life quickly and easily, without some serious work one does, often unbeknownst to himself, to prepare himself for the kind of life that he feels makes sense.

Who are the star participants among this year’s faculty members?

All of them are stars in my book, as well as by the lights of great many readers in north America and abroad – although not in the same sense or scope as, say, Brad Pitt or Jennifer Lopez or the authors of mega-bestsellers on The New York Times bestseller list are stars. The literary world, at least in North America, is not about starship – there’re not enough readers of serious literature in modern world to make them stars in the commonplace meaning of the term – but it is, rather, about being consistently interesting and thoughtful and contemporary and doing meaningful things with one’s writing, charting new literary routes, taking reader to the place where serious questions about the serious life’s issues get asked… and not necessarily answered, because life itself is an open-ended proposition, with no ready-made answers or recipes for happiness on the offer.

One of the great advantages of being an independent literary program run by writers is that we’re free in our choice of invited faculty. Over the fourteen years of SLS’s existence, we’ve brought to our programs the veritable Who’s Who of the North American and international letters: people who are innately curious about the different paradigms of life in various places and who – although they easily could afford to come to those places on their own – Russia, Lithuania, Kenya -- wouldn’t be content with status of the mere tourists, which they inevitably would be without the familiarity with and immersion in the local literary and arts scene.

Another very distinct feature of SLS separating it from any other program of its kind: we draw no dividing lines between the well-known, famous and accomplished writers on the faculty -- and the beginning writers constituting the bulk of the program participants. Everyone’s in the same boat on the SLS programs; everyone’s in on the same type of discovery. Our programs are about shifting and accelerating the paradigm of one’s literary practice, and so we put people in highly unfamiliar (although on the surface recognizable) settings – and everyone is lost there in the company of other writers; everyone is lost within a findable context. Everyone is brought together by the pressure of the sheer strangeness, unfamiliarity of the surroundings. A very famous writer therefore can drink beer till two in the morning in the company of twenty-year-old undergraduate students of creative writing and talk to them as equals about literature… or whatever else people talk about at two in the morning while drinking beer Writing is an enterprise where the rank has no meaning. A famous writer is nothing but yesterday’s novice. Over the course of my teaching career, I’ve seen enough talented but not necessarily hard-working people, and enough not too brightly gifted (on the surface) yet extremely ambitious and serious and diligent your writers, to know that in writing, dedication to the process and practice of literature inevitably trumps the bright but sometimes shallow flame of natural talent. Talent is not always to be found on the surface of one’s early writing. People come into the possession of their talent, their true literary voices, over the long period of hard work.

This is the third time that you run the program in Vilnius. Why?

I am very glad we’re holding SLS programs in Lithuania now,. The idea to open one came after we had decided to suspend our sessions in St. Petersburg, which we ran for 10 years straight and brought roughly a thousand students to the city on the Neva. The constraints of available space would preclude me at this point from talking about the reasons why I’ve always found Lithuania fascinating – going back to the early years of my Soviet adolescence. But those reasons were indeed numerous, and memorable.

So I decided to see if we could hold a program in a place which, unlike St. Petersburg, Russia, is not that easily and readily recognizable to the North American literary community; does not hold the same kind of raw mystique perhaps that Russia possesses – not to mention Kenya, which is the site of another one of our long-running programs.

Lithuania, of course, is the geographic heart of Europe – but more than that, it is the spot where the tectonic plates of European history have clashed over the centuries, and currently are clashing as well; it is a place of transition from the old, divided Europe, to the new, unified yet still painfully unequal one.

To me, of course, it matters a great deal that this is a post-Soviet space – and of course, and very meaningfully, it is of essential importance to me that Lithuania was the place of the greatest concentration of Jewish people in Europe relative to the native population, for centuries and immediately prior to the WWII, and then became the site of the greatest tragedy in the history of the Jewish people. My ancestry, originally, is from the larger Litvak area: Belarussian border with Lithuania, and Latvia. There is a large agglomeration of factor that have caused me to want to hold the program here, both personal and intensely objective ones

One of the aims of the program is to set in motion a cultural, literary and, most importantly, creative exchange between the visiting established authors and writers to be and the local literary community. Based on previous SLS Vilnius, how does that work, does that collaboration bare any fruit?

We’re working on it. SLS, basically, over the years, without setting this as a major goal expressly, has positioned itself as a moveable platform of sorts upon which the North American and the international literary communities can meet. Over time, we have had lots of former SLS participants collaborating on literary projects with their counterparts from Russia and Kenya and Canada; and we‘re intent on seeing the same happen in the case of the Lithuanian literary community. There have already been some poetry translations of contemporary Lithuanian poetry done by our program participants, on a fairly significant scale, and some work already has been published. We’re looking to expand that effort further still, and on a considerable scale. We are bringing to Lithuania some of the leading publishing-house and literary-magazine editors, who always are interested in discovering the new voices from a variety of places. Ask me the same question in a year: after all, we have only just started our program in Lithuania: three years is a short time. Ars longa, vita brevis.

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - (0) Comment

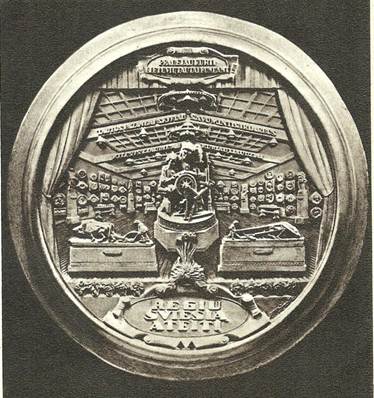

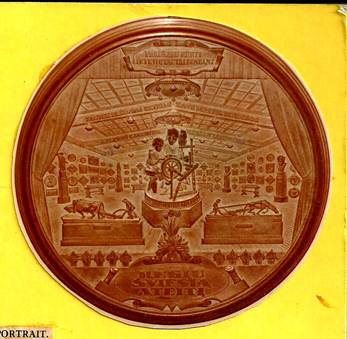

The medals of

Petras Rimsa

Lithuanian medallic art is an especially interesting area of study in the numismatic hobby. Individual medals struck by various persons or groups convey the specifics of the history of Lithuania and its people.

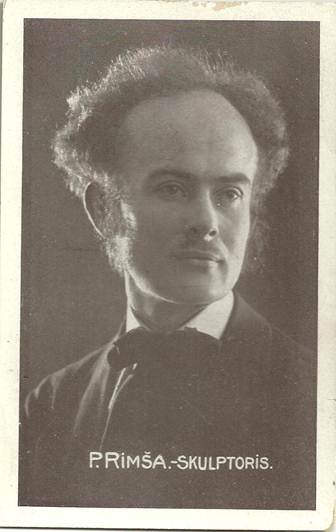

Petras Rimsa in 1957

|

By Frank Passic, Albion, Michigan Lithuania’s most outstanding medalist was sculptor Petras Rimsa (1881-1961), a contemporary of Germany’s medalist Karl Goetz. Many of Rimsa’s designs reflect Lithuania’s patriotic themes and range from religious subject matter to sarcastic political commentary. Since the reestablishment of Lithuanian independence in the 1990s, Rimsa’s medals have again become popular and highly sought after by Lithuanian collectors. To meet the demand, there are even contemporary reproductions of Rimsa’s early 20th century medals. Petras Rimsa was born November 11, 1881, in the Lithuanian village of Naudziai. His parents were farmers of the Suvalkai Province under Czarist rule, and in this rural setting young Petras aspired to be an artist. He was especially talented and showed a marked tendency for work that required skill, accuracy and patience. As a young boy he spent much of his leisure time whittling and decorating household articles and farm implements. Before long he had acquired the name of “Master” in his village in recognition of his artistic work. At the age of 17, Petras left his village for Warsaw, Poland, to study art under the tutelage of Polish sculpture Welonski. He then traveled to France to further study at the Ecole des Beaux Arts under Professor Antoin Mercie. After completing his courses there, Rimsa traveled to various European centers of art and culture, continually increasing his knowledge and skill.

Upon his return to Lithuania in 1906, Rimsa immersed himself in local Lithuanian cultural activities, helped to establish the Lithuanian Art Association and participated in the first Lithuanian Art Exhibit in 1907. Here he exhibited his most famous sculptural work, “The Lithuanian School,” (also known as the “School of Misery”) which received much critical acclaim. This masterpiece represents the Lithuanian school between the years 1864 and 1904 when the Russian government placed the strictest ban on Lithuanian literature. The sculpture shows a mother secretly teaching her child the Lithuanian language. The alert and watchful dog beside the child shows the constant fear with which the school operated. In 1993 the Bank of Lithuania illustrated Rimsa’s “Lithuanian School” on the back side of the 5 litai banknote designed by artist Gedrius Jonaitis and printed by the Thomas De La Rue printing company. Ironically, Rimsa had submitted sketches to the Bank of Lithuania for a proposed 50 litas banknote design during the 1920s in which he illustrated the “Lithuanian School” on the face. That design however was rejected at the time by bank officials.

P-55 1993 Lithuania 5 Litas banknote back side featuring the “Lithuanian School.”

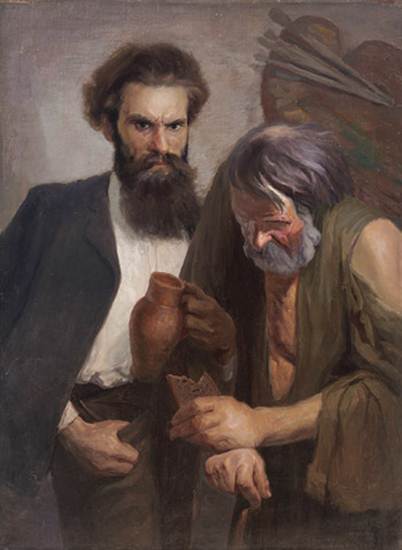

In 1907 Rimsa exhibited his other famous work, Artojas (The Ploughman) which expressed Lithuania’s utter misery under Russian occupation. The piece depicts the ploughman with his beast of burden and the plough made by his own hands as they together force the hard and weedy soil to yield a crop. The Ploughman associated Rimsa’s name with Lithuania’s struggle for national independence. In 1911, the Russian Imperial Society of Arts awarded him a large cash prize for this work. Rimsa’s work THE PLOUGHMAN, created in 1922, graphically depicts the country’s misery under Russian occupation.

The outbreak of World War I brought severe hardships to Rimsa and his countrymen, and Rimsa was forced to labor in munitions factories and as a merchant. After Lithuanian independence was restored in 1918, he returned to his home in the Lithuanian capital of Vilnius and continued his artwork.

Petras Rimsa in the 1920s

His return to Vilnius, however, was short-lived. In 1920 the military invasion of Lithuania by Poland and occupation of Vilnius by Polish troops forced Rimsa to flee the city. His studio was lost and a lasting bitterness about the situation was implanted, a passion that was later reflected in his medallic work. After losing his studio in Vilnius, Rimsa journeyed to Berlin and other European cities. He finally returned to Lithuania and made his home in Kaunas, the temporary capital of the country.

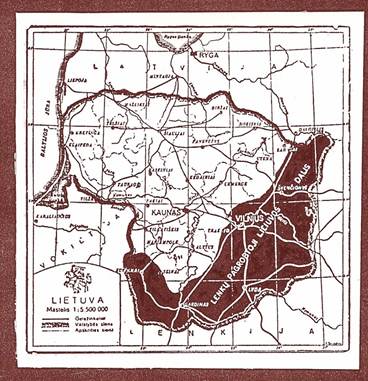

The portion of Lithuania occupied by Poland 1920-1939. Accordingly, when the subject of the Polish occupation of Lithuania’s capital came up in conversation, Rimsa suddenly became very eloquent and spoke as an expert on the subject. Rimsa toured the United States in 1936 and 1937, exhibiting his works in Boston, Chicago, Cleveland, Detroit, Pittsburg, New York and other cities. Critics marveled at his artistic abilities. Paul Bird of The Art Digest commented, “An artist of unusual graphic power, he also produces ornate linear sculptures, decorated from head to foot with fantastic designs.” Carlyle Burrows of the New York Herald Tribune wrote, “Medals like these celebrating the Congress of Vilnius, and the establishment of the first ecclesiastical province of Lithuania are forcefully modeled in their essential details, while showing meticulous elaboration of the backgrounds.” Eleanor Jewett of the Chicago Daily Tribune remarked, “There seems, in fact, no end to the genius of this artist. He cannot be classified as a modern or non-modern, but ranks with the unticketed immortals.” In the introduction to the official programs at the exhibition held at the International Institute in Boston, January 30 through February 12, 1937, the Consul General of Lithuania, Jonas Budrys, remarked: “Petras Rimsa is one of the most prominent sculptors of Lithuania. His creations are valued very highly not only in Lithuania, but also elsewhere. They portray the spirit of national Lithuanian art, they carry one into the realms of the unknown, unexplored futurism...His numerous medallions disclose the finesse of an accomplished artist. In appreciation of this recognition, and in appreciation of the talents of the sculptor, we offer this exhibit to art lovers, and we hope that it will tend to bring the American public closer to Lithuanian talents, and to the Lithuanian people as a whole.” 1 Rimsa’s success in the United States was due largely to the efforts of the noted Lithuanian-American numismatist, Dr. Alexander M. Rackus (1893-1965). An avid collector, Rackus belonged to the American Numismatist Association and wrote numerous articles for the Numismatist in the 1920s and 1930s. In his recollections, Rimsa remarked:

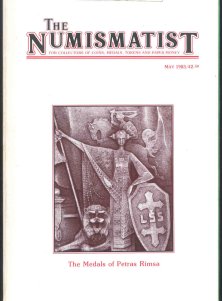

Dr. Aleksandras M. Rackus (1893-1965) “Aleksandras Rackus was the first collector with such a strong passion that I had met and knew. Of course, he had set his heart on my medals. They were items which, if was said, could be shown anywhere in the world. And Dr. Rackus took my medals to coin shows everywhere in the world. They were discussed quite often in American numismatic conventions. And it was worthwhile ... My medals apparently attracted the notice of Americans. Rackus wrote, “Visitors to numismatic shows, passing indifferently by other exhibits, would always stop at those cases in which were displayed Petras Rimsa medals, and enjoying themselves would remain by the half-hour.” Even American sculptors eyed them approvingly. As an example, the sculptor-medalist J. Henris Ripstra wrote me on April 18, 1931, as follows: “I recently viewed your medal collection, exhibited by Dr. Al. Rackus as the Chicago Coin Club. They pleased me very much, and I congratulate you upon your style and technique. If possible, I would like to acquire a collection of those medals.” And thus my medals found their way into the world.” 2 Following World War II, Rimsa stayed in Soviet-occupied Lithuania, where the communists gave him a large studio to replace his cramped one in Kaunas. Rimsa continued to illustrate books, write and design medals. Unhappy with the Soviet system, he frequently refused work in his later years, officially blaming his “old age,” as his personal letters to the West revealed. Rimsa died in Vilnius on October 2, 1961. His recollections were published in 1964, Rimsa’s pre-World War II medals were struck by Huguenin Freres & Company of Le Locle, Switzerland. This firm also manufactured Lithuanian military orders and decorations. Rimsa’s medals were struck in bronze, in various sizes of 100, 75, 60, 35 and 25 millimeters in diameter. Personal editions presented to close friends or dignitaries were often of silver or gold wash, and Huguenin Freres & Company customarily presented Rimsa with a 150-gram gold striking of each of his designs. On a personal note, in 1979, this writer was able to view various Rimsa medals on public display inside the “Stained Glass Museum” (The Church of Saint Michael the Archangel) in Kaunas, during my visit to Soviet-occupied Lithuania. I was also able to view Rimsa medals in private collections. Later I learned that my maternal great-grandmother was a Rimsa, although probably not related to the sculptor. Although I have only been able to obtain just a couple of his medals for my collection, I have still been fascinated about the details found on these medals, and the diversity of themes that the sculptor tackled. In May, 1983 the American Numismatic Association published my listing of Rimsa medals in their magazine The Numismatist. A close-up of the Congress of Vilnius medal was featured on the front cover. Cover of The Numismatist, May 1983 featuring Petras Rimsa medal detail.

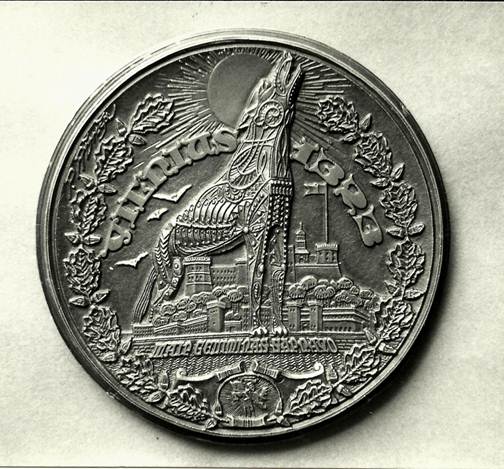

The following is a listing and description of the medals of the famous Lithuanian medalist, Petras Rimsa. 1. Vilnius, Capital of Lithuania This medal commemorates the 600th anniversary of the founding of the Lithuanian capital city of Vilnius. The anniversary occurred in 1923 when the city was under Polish occupation. VILNIUS, CAPITAL OF LITHUANIA Known Mintages: 35 centimeter medal, private issue, only a few struck; 75-millimeter medal—300 struck; 20 100mm personal specimens cast in bronze. Obverse: Featured is Grand Duke Gediminas, dressed in chain mail and holding a downward pointing sword in his right hand. On his left shoulder is a decorative mask of a lion’s head, symbolic of Gediminas reputation as the “Lithuanian Lion.” Gediminas began the dynasty of Lithuanian rules that lasted almost 300 years. Ruling from 1316 to 1341, Gediminas completed the unification of the Lithuanian tribes and expanded the territory of the nation. The inscription reads GEDIMINAS DIDYSIS LIETUVOS KUNIGAIKSTIS MCCCXVI-MCCCXLI, which translates “Gediminas the Great, Grand Duke of Lithuania 1316-1341.” Reverse: Shown is Gediminas castle, the ruins of which are still found in Vilnius today. The inscription reads VILNIUS LIETUVOS SOSTINE, meaning “Vilnius, Capital of Lithuania.” At the bottom is Vytis (the knight), Lithuania’s national emblem, and the anniversary dates, MCCCXXIII-MCMXXIII (1323-1923). Rimsa also produced a plaque featuring the Gediminas design.

Gediminas plaque 2. Regaining Klaipeda In 1252 the Livonian Order invaded western Lithuania, reached the Courish Lagoon and erected a stronghold on the site of a native Lithuanian village. Pope Innocent IV noted in 1253 that the stronghold had clearly been built in Lithuanian territory. Renamed “Memelburg”, the city was a source of boundary conflicts between Lithuania and the Teutonic knights and other warring factions for many centuries. After World War I, the Klaipeda region was placed under Allied control and Lithuanians feared the city would be returned to the Germans or taken over by Poland. In January 1923, the Lithuanians staged an insurrection and successfully regained the city. Known Mintages: 10,000 specimens were struck in 1927, some 60 millimeters in diameter and the remainder 35 millimeters. In addition, two personal editions were issued.

Obverse: Shown is a Lithuanian of the Klaipeda district (right) calling to arms a volunteer of independent Lithuania (left). The center depicts the defender of Lithuania receiving a sword from a patriotic woman, with the city in the background. Surrounding this is the inscription, KAS MUSU KOVA IGYSIM, which translates “that which is ours we shall fight to retain.” In the left oval is the Vytis emblem, opposite is the coat-of-arms of the city. The bottom contain a sword pointed upward, with the words, I-9 KLAIPEDA 1923, referring to January 9, 1923, when the call for help went out. A wreath of oak leaves surrounds the design, and the emblem of the Lithuanian Riflemen’s Union, the double-barred cross, appears above.

Obverse Reverse: Shown is Klaipeda after reunification. Major Lithuania (left) joins hands with Minor Lithuania (right), representing unity of the land and waters of Lithuania. In the center, the defender has returned, and is being bestowed with the laurel wreath of victory and honor. At the bottom is a downward pointed sword with the inscription 1-19 KLAIPEDA 1923, signifying the day of the insurrection. Below are twigs from the Lithuanian national flower, the ruta (rue). In the let oval is a sailboat, symbolic of the recreation of the area; opposite is placed a rake and a plow, symbolic of the industry and agriculture of the area. At the top of the medal is the Order of the Cross of Vytis, Lithuania’s highest military order for honorable service at that time. The legend reads ISKOVOTA-MYLET MOKESIM, which means “That which we have regained, we will know how to cherish.” Rimsa later issued another version of the medal with the inscription AMZIUS BUDEJE LAISVE LAIMEJOM, which translates “having waited for ages, we won freedom.” Specimens with the alternate inscription also bear the date 1-20 on the bottom, signifying the day victory was achieved. The obverse of the later version bears the inscription VADOUKIS PATS, IR BUSI LAISVAS which means “Save Yourself and you Will be Free.”

Reverse

Rimsa’s Signature on the Klaipeda Medal.

3. Congress of Vilnius Following the Revolt of 1905 in the Russian Empire, Lithuanian nationalists, concerned with the question of autonomy for Lithuania, gathered in Vilnius on November 21-22, 1905. Headed by Jonas Basanavicius, the 2000 member assembly resolved that the Czar was the enemy of Lithuania, that Lithuania should be autonomous, that Russian influences in Lithuania must be removed and that the Lithuanian language and culture should reign supreme in the country. Within a few weeks after the assembly dispersed, Lithuanians held elections, ousting Russian officials. However, the Russian government soon enacted repressive measures against those who had been active in carrying out the resolutions. This medal commemorates the 20th anniversary of the Congress of Vilnius.

Obverse: The design focuses on the outline of the city of Vilnius, with the Hill of Gediminas in the background. The inscription reads, DIDYSIS VILNIAUS SEIMAS, which means “The Great Congress of Vilnius.” At the top is the phrase from the Lithuanian national anthem: IS PRAEITIES TAVE SUNUS TE STUORTBE SEMIA, which translates “may your sons draw strength from the past.”

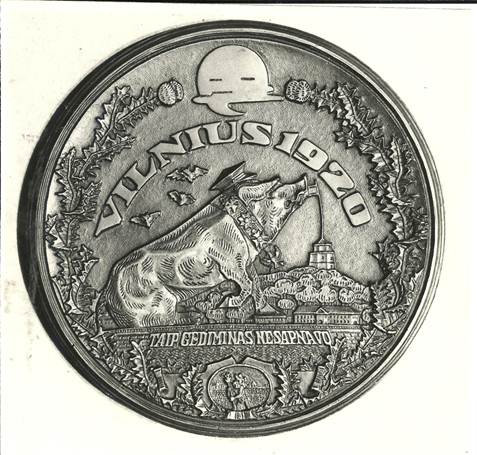

Reverse: At the top is the date 1925. Depicted is independent Lithuania standing before her throne, holding the national emblem Vytis. The chain of slavery is at her feet, and the lion at her side represents strength. Her left arm rests upon the shield with the double-barred cross, the emblem of the Lithuanian Riflemen’s Union (Lietuvos Sauliu Sajunga), and bears its initials, “L.S.S.” 4. Vilnius in 1323; Vilnius in 1920 This is the first of several anti-Polish medals issued in protest of the Polish occupation of Vilnius.

Reverse

Reverse: In sharp contrast with the obverse, the scene depicts Vilnius in 1920 after it was seized by Poland. At the base of the castle ruins is inscribed TAIP GEDIMINAS NESAPNAVO, which means “this was not Gediminas’s dream.” The center is dominated by a large pig furiously devouring the Lithuanian flag. The collar of the pig is adorned with Polish military symbols. The pig is wearing a militaristic-style hat, representing the treaty violation and method used to seize the city. To the left, instead of three birds, hover three bats, signifying the evilness of the pig’s presence. The legend reads VILNIUS 1920. The sun has been replaced by a dark moon, and the design is surrounded by a wreath of thistles and thorns. At the bottom is the coat-of-arms of Vilnius. Rimsa also printed and circulated postcards with this same theme, and one is illustrated here.

Rimsa postcard

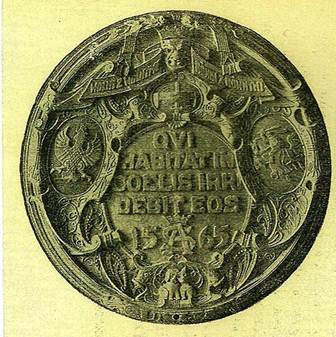

5. Unity and War This medal, entitled Unity and War (Unija ir Kova), resurrects Lithuanian numismatic history as a theme of conflict between the Lithuanians and the Poles when referring to the occupation of Vilnius by Poland.

Obverse: Depicted is the Lithuanian 3 grosz coin of 1565, minted during the reign of Grand Duke Sigismund August. This coin is one of the most famous in Lithuanian numismatic history. When minted, it was an international embarrassment to the Poles, and a strong expression of Lithuanian autonomy. On this coin, the Vytis emblem was transferred to the obverse side of the coin, and the monogram of Sigismund August (where formerly the bust of the ruler was displayed) was transferred to the reverse between the date numerals at the bottom. In Latin on the reverse is the biting sentence from the Psalm of David: QUI HABITAT IN COELIS IRRIDEBIT EOS (Psalm 2:4), which means “He who sits in the heavens laughs at them.” This passage was purposely included on the coin by officials at the Lithuanian Mint as a response to Polish clamoring about the Lithuanian 3 grosz having twenty percent more intrinsic value than it’s Polish counterpart, and for placing Lithuanian symbols and inscriptions in prominent positions on coins minted in Vilnius. Jonas K. Karys, director of the Lithuanian Mint from 1936-1939 wrote on the subject by stating: “So the leadership of the Mint and eminent Lithuanians standing in back of it in Vilnius, on at least one occasion gave the Poles what was coming to them. The Poles, full of outrage, descended upon Sigismund August, who in this case was least at fault. When those 3-grosz coins appeared in Polish provinces, the storm boiled over. The bishop of Cracow, F. Krasinski supported the indignation of the Polish boyars, and sent a special letter addressed to Sigismund August. Having received that letter, the ruler personally investigated the case and at the beginning of 1566, totally banned further striking of that coin.” 3 The coin depicted on this medal bears the Gumowski number G-623 and was minted in 1565 and 1566.

1566 3-grosz, satirical side.

The image of the coin appears in the center of the medal. At the top of the medal is a favorite Polish proverb WOLNIZ WOLNYMI; ROWNIZ ROWNYMI, which translates “the free with the free, equal with equals.” Accordingly, the phrase is separated by a mask, signifying the hypocrisy of the Polish words. Instead of the two nationalities being equals, the Polonization of Lithuania subsequently occurred. This was especially true during the period of the occupation of Vilnius by Poland, when Lithuanian schools, customs, and organizations were squelched, and leaders imprisoned. At the bottom is shown a dog and a cat, which represent the incompatibility of the union. The word UNIJA appears at the very bottom of the edge. To the left in an oval space is found the Polish eagle; opposite is the Lithuanian emblem, Vytis. Reverse: Entitled KOVA (war) on the bottom rim, this scene depicts Vytis in combat with the Polish eagle. It is the prophecy of the minters of 1565 fulfilled. The dog and cat, represented only by heads on the side rims, are incompatible and far apart. Rimsa’s signature appears at the three o’clock position, and the date 1925 appears at the two o’clock position.

UNITY AND WAR, Reverse.

1566 3-grosz, Vytis side.

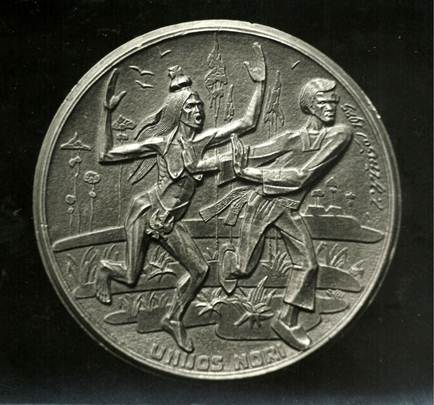

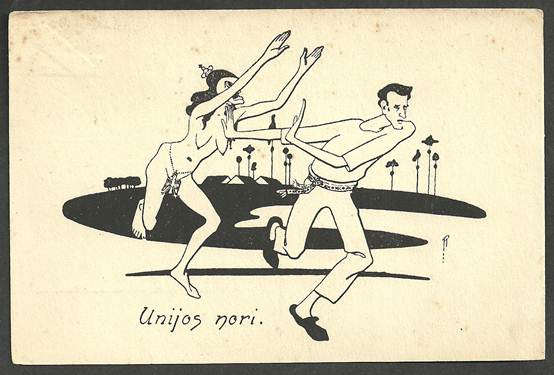

6. Union Desired

Known Mintage: Only 12 specimens are estimated to have been struck, all 100 millimeters in diameter. Bronze plaques are also known to exist. Obverse: Entitled UNIJOS NORI (Union Desired), this extremely grotesque theme represents a naked and prostitute Poland offering herself forcibly to a fleeing Lithuanian male in national costume. Rimsa’s signature and the date 1925 are located at the two o’clock position. This same scene was also circulated on postcards produced by Rimsa, one of which is illustrated here.

“Union Desired” postcard produced by Rimsa.

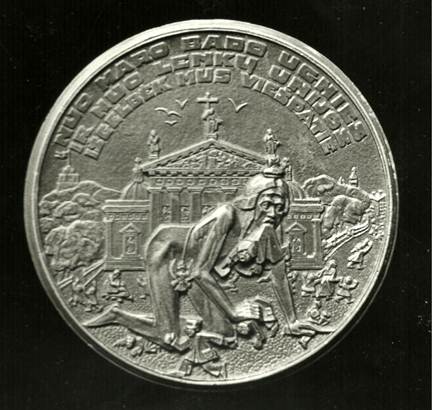

Reverse: Depicted is the Union rejected, with Poland exterminating all that is Lithuanian in Vilnius. In 1925, the Polish occupational regime began an assault on Lithuanian school children for their outspoken nationalism. As a protest, Rimsa graphically portrayed the same deranged Polish figure devouring innocent Lithuanian school children in front of the famous Cathedral of Vilnius. The children are shown fleeing from the Polish terror. The legend reads NUO MARO BADO UGINIES IR NUO LENKU UNIJOS ISGELBEK MUS VIESPATIE, which translates “from pestilence, famine, fire and union with Poland, Deliver us O Lord!”

Reverse

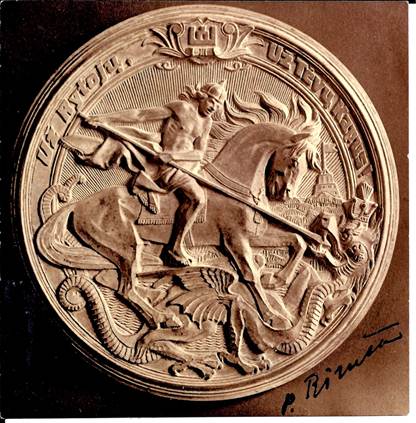

7. Let us Liberate Vilnius Obverse: Vytis is shown in violent combat, spearing the Polish dragon, with the Hill of Gediminas on the right. The top inscription is separated from the Columns of Gediminas emblem, and reads UZ RYTOJU – UZ TEVU KAPUS! which translates “For the Future – for the Graves of our Ancestors!”

Obverse

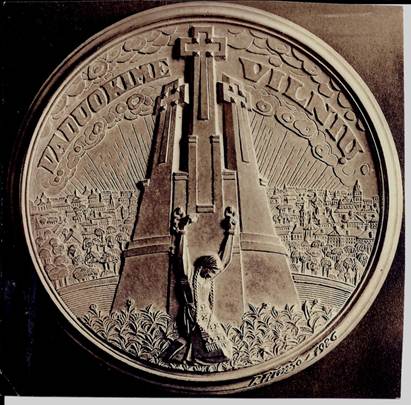

Reverse: Portrayed is the monument Three Crosses, which stands on the high Bare Mountain on the steep right bank of the Vilnia River. This monument was erected in the early 17th century and remained a permanent feature of the cityscape until 1869, when it was destroyed. After World War I, artist Anton Wiwulski designed a new monument that was painted in white. This monument was blown up by the communists in 1950. It has since been recreated. The legend VADUOKIME VILNIU, which translates “Let us Liberate Vilnius,” appears at the top, with Vilnius in the background. Below is maiden Lithuania, who is chained to the monument amidst a bed of ruta. She is awaiting Vytis to save her from Poland. At the five o’clock position appears Rimsa’s signature and the date 1926.

Reverse

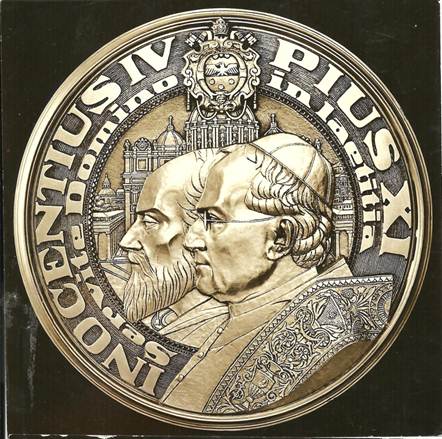

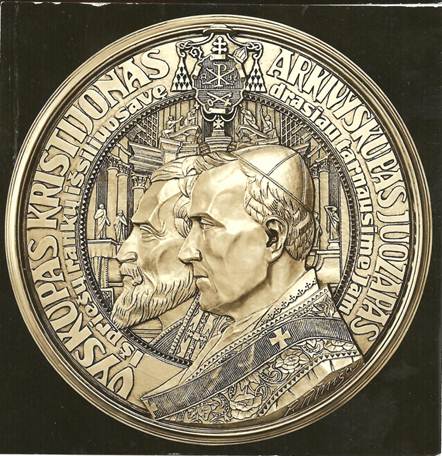

8. First Ecclesiastical Province of Lithuania During the era of the Republic of Lithuania, not all the Lithuanian-inhabited areas were included because of the large areas occupied by Poland. Roman Catholic Lithuanians sought to prevent the Holy See in Rome from recognizing Polish military conquests, but were unsuccessful. The archdiocese of Vilnius was transferred to Poland, and the Poles forced Lithuanian Bishop Jurgis Matulaitis to resign. In order to appease the Lithuanian church, Pope Pius XI raised Matulaitis to the office of titular archbishop and named him apostolic visitation to Lithuania, with the Metropolitan See located in the temporary capital of Kaunas. The ecclesiastical province of Lithuania received an official blessing from Pope Pius XI on April 26, 1926. Rimsa’s medal was issued in commemoration of the first ecclesiastical province of Lithuania. Lithuania first became a Christian nation in 1251 when Lithuania’s Mindaugas entered into relations with the Holy See, and Pope Innocent IV established the diocese of Lithuania. In 1252 Mindaugas was crowned King of Lithuania, in the name of Pope Innocent IV, who declared him to be a “special son of the Holy Roman Church.” Obverse: In the center of the medal are the images of Pope Innocent IV (left) and Pope Pius XI (right) who founded respectively, the first Bishopric and the first Metropolitan See in Lithuania. In the background is the Bascilica of St. Peter in Rome, and at the top of the personal insignia of Pope Pius XI.

Obverse Reverse: Featured is the image of Bishop Kristijonas (Christian) (left), the first Lithuanian bishop, who received his appointment from Pope Innocent IV on July 17, 1251. Prior to his appointment Kristijonas was a priest of the Teutonic Order under the German archbishop of Riga. Kristijonas established his See in the pagan Samogitian region of Lithuania, but only remained until 1259 when he left for Germany and ended his days in 1270 as a suffragan bishop of Mainz.

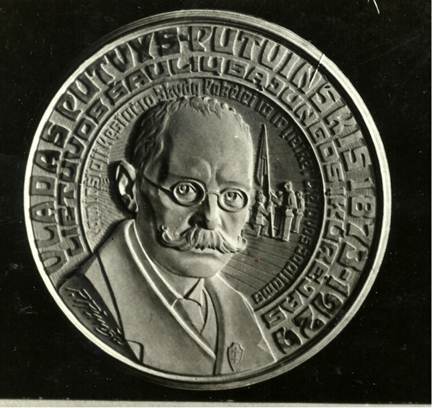

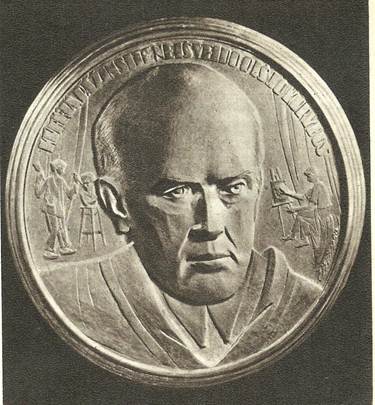

On the right is the image of Archbishop Juozapas Skvireckas (1873-1959), the first Archbishop of Lithuania. Skvireckas was a well-known scholar and the theologian who translated the Bible into the Lithuanian language. He governed the Kaunas archdiocese for almost the entire period of Lithuanian independence. He fled Soviet-occupied Lithuania in 1944 and went to a convent in the Austrian Alps, where he lived until his death. The arms of Bishop Juozapas disappear at the top of the medal. The inscription reads, IS PRIESU RANKU ISSILIUSAVE DRASIAU TARNAUSIME JAM, which translates “having liberated ourselves from the enemy’s hands, we shall serve with more courage.” The names of the two men appear around the perimeter of the medal. 9. In Honor of Vladas Putvys-Putvinskis This medal was issued in honor of the founder of the Lithuanian Riflemen’s Union (Lietuvos Sauliu Sajunga), Vladas Gerardas Putvinskis-Putvys (1873-1959). Putvys was descended from an old Lithuanian noble family, and his estates became important centers for secret Lithuanian activities in the late 19th century. He founded the Riflemen’s Union in 1919 and was elected its first president and commander-in-chief. Obverse: Shown is the image of the late organizer. In the background is depicted the ceremony of the presentation of the colors. The legend reads VLADAS PUTVYS-PUTVINSKIS 1873-1929, LIETUVOS SAULIU SAJUNGOS I KUREJAS, which translates “Vladas Putvys-Putvinskis 1873-1929, founder of the Lithuanian Riflemen’s Union.” A smaller inscription in the center circular area translates, “thou has raised the forgotten shield of Kestutis and presented it to the Lithuanian Riflemen’s Union.”

Obverse Reverse: At the top is the Vytis emblem, opposite of which is the Columns of Gediminas. In the center is the insignia of the Riflemen’s Union, which was designated by Rimsa. The inscription reads IR SIRDI IR PROTA TEVYNES RYTOJUI, which translates “both heart and mind for the nation’s future.”

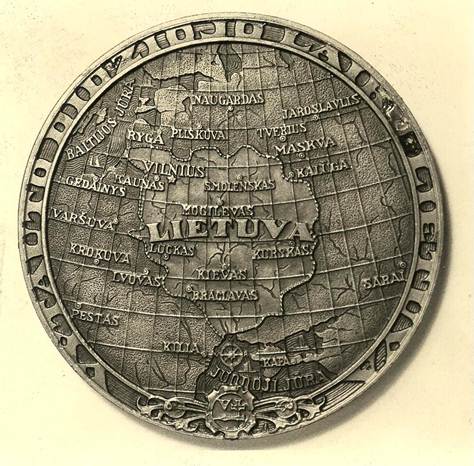

Reverse 10. Vytautas the Great Lithuania’s greatest patriarch, Vytautas the Great, reigned as Grand Duke of Lithuania from 1392 to 1430. Vytautas expanded Lithuanian territory and made it one of the leading European powers of his day. He led the Lithuanian army and allies to a spectacular victory over the Teutonic Knights at the epoch-making battle of Zalgiris/Tannenberg/Grunwald in 1410. This event stopped the advance of the Knights, assuring independence for Lithuania and other eastern European nations. The Vytautas the Great medal is Rimsa’s most well known. Struck in many sizes (the original was 35 millimeters), this medal has the largest mintage of all Rimsa’s medals: 17,000 total. The obverse design became the emblem for the 500th anniversary celebration of the patriarch’s death. During Rimsa’s 1936-1937 tour of the United States, he presented a specimen of the Vytautas medal to the American Numismatic Association. Obverse: Shown is the image of Vytautas the Great. The legend reads VYTAUTAS DIDYSIS 1430-1930, which translates “Vytautas the Great 1430-1930.” In the background is depicted the Battle of Zalgiris/Tannenberg/Grunwald, similar to that which is found on Polish artist Jan Matejko’s famous rendition of the battle painted in 1878.

Reverse: Featured on the reverse is a map of Lithuania in the time of Vytautas. During the 15th century Lithuania stretched from the Baltic to the Black Sea, covering 350,000 square miles. Names of the cities are in Lithuanian. At the bottom appears the “Vytautas Symbol,” a popular emblem in 1930 based upon supposed ancient denars struck during Vytautas’s reign. The legend reads VYTAUTAS DIDZIO LAIKU LIETUVA, which means “Lithuania in the time of Vytautas the Great.”

Reverse

11. Riflemen’s Union Star Medal The Riflemen’s Union Star Medal was issued in 1939 as a decoration for the Lithuanian Riflemen’s Union. Each medal was presented with a blue/green ribbon with two white stripes. Accompanying each medal was a presentation certificate that included a likeness of the medal. The certificate presented to Dr. Alexander M. Rackus, translates: “Republic of Lithuania. Riflemen’s Union Star Medal. By the act of the Minister of Defense and in the name of the President of the Republic of Lithuania. Dr. Alexander Rackus is awarded the Riflemen’s Union Star Medal. Established in 1939 on the twentieth anniversary of the founding of the Riflemen’s Union. Signed, Brig. General S. Rastikis, Commander-in-Chief of the Army; Signed, Colonel Saladzious, Chief of the Riflemen’s Union Association. Kaunas, 1939, June 24, No. 8367.” Obverse: The emblem of the National Guard, designing by Rimsa, is featured. At the top is depicted a miniature Riflemen’s Union Star, the main order of the Riflemen’s Union. A wreath of oak leaves surrounds the sides, with Rimsa’s “Wise Owl” emblem perched atop an open book.

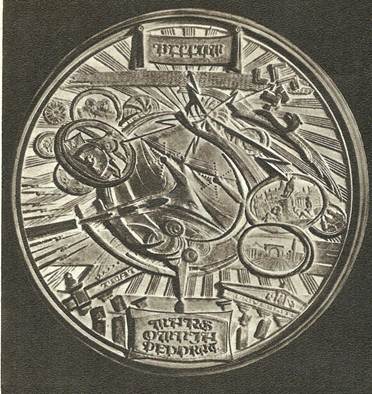

Reverse 12. War and Peace This is the first of Rimsa’s post-World War II medals, designed with the approval of the communist occupational regime in Lithuania. Struck in bronze, this medal measures 34.5 millimeters in diameter. Obverse: Entitled BELLUM (war), this medal shows an intense conflict. The loops of Rimsa’s design contain scenes from major European cities. Bayonets point upward, and a broken swastika appears at the one o’clock position under which is a dead German eagle. In the center a ghost emerges, symbolizing man, the initiator of wars. The lower cartouche bears the inscription MARS OMNIA DEVORAT, which translates “War Destroys Everything.” The “death loops” was an artistic technique that Rimsa had previously used in a bas-relief to depict the ill-fated flight of the Lituanica in 1933, in which various depictions were presented. A 1937 Rimsa exhibition program stated: “There is neither top nor bottom, neither right side nor left, as the view is good from all sides.” This appears to be the case with the obverse of the “War and Peace” medal.

Reverse: Entitled PAX (peace), the dove of peace appears, observing the nation at work in harmony, with a girl trumpeting the victory flag above. Rays of the sun shine brightly in the background. The bottom inscription reads LABOR OMNIA CREAT, which means “Labor Creates Everything.”

Reverse

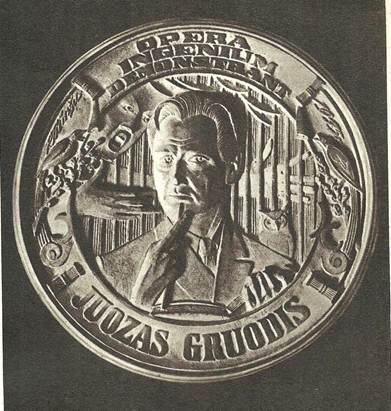

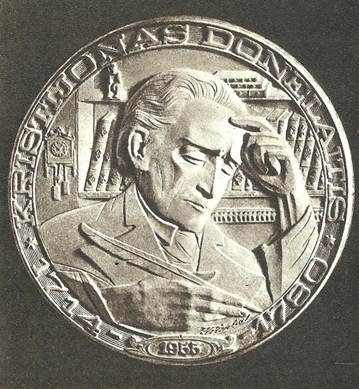

13. In Honor of Juozas Gruodis This medal was struck in bronze in 1945, is a 23.5 millimeters in diameter, and honors the then-living Lithuanian composer, Juozas Groudis. Born in Rakenai on December 20, 1884, Gruodis studies musical composition in Moscow from 1914 to 1916, and in Leipzig from 1920 to 1924. Upon his return from Germany, he became director and professor of composition at the Kaunas School of Music until his death in 1948. Obverse: Featured is the image of Gruodis, with musical and operatic symbols in the background. Included above Gruodis’ left shoulder is Rimsa’s “Wise Owl” emblem. The legend reads OPERA INGENIUM DEMONSTRANT, which translates “his work show ingenuity.” Rimsa’s signature appears in the upper left with the date 1945 opposite. JUOZAS GRUODIS appears under the bust.

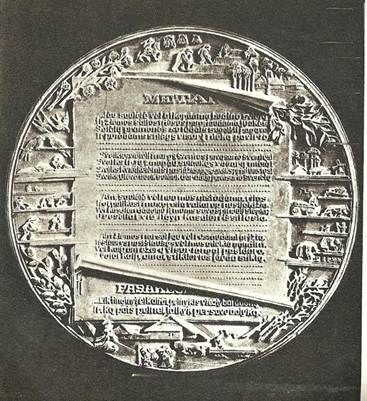

Obverse Reverse: Shown are several titled score sheets of Gruodis’ works.

Reverse