THE VOICE OF INTERNATIONAL LITHUANIA

|

VilNews has its own Google archive! Type a word in the above search box to find any article.

You can also follow us on Facebook. We have two different pages. Click to open and join.

|

Fri, 14th September, 2012 - (1) Comment

Main events in

Lithuania’s history

(based on “The official gateway of Lithuania”, Government of

Lithuania website, adopted and modified by dr. S. Backaitis)

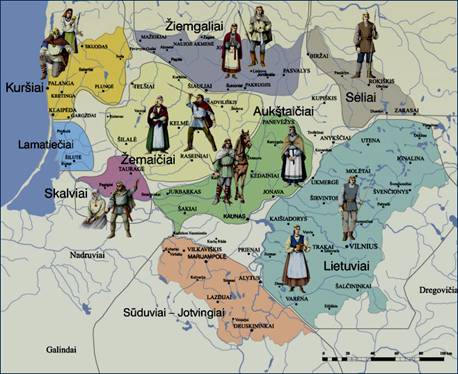

The first settlers arrived at the eastern shore region of the Baltic Sea in approximately 12,000 B. C. In 3,000–500 B. C., the Indo-European Balts came to live here. Between the 5th and 8th centuries tribal groupings in the western territories included: Prussians, Yotvingians, Curronians, Zemgalians, Lithuanians and Latgalians. In the 10th century the pagan Baltic tribes became the target of christianization by Western Europe. In 1009, the name of Lithuania was mentioned for the first time in the written account of the mission of St. Bruno in Quedlinburg Annals.

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

Fri, 14th September, 2012 - (0) Comment

Gediminas – King of

Gediminas – King of

Lithuania & Russians

Gediminas' Tower (Gedimino pilies bokštas) is the only remaining part of the

Upper Castle in Vilnius. The first fortifications were built of wood

by King Gediminas. Later the first brick castle was completed

in 1409 by Vytautas the Great.

Gediminas (1275 - 1341) was the one founding Vilnius as the capital of Lithuania. In works of history Gediminas is referred to as the Grand Duke of Lithuania, but he called himself, and was titled in all official documents, the King of Lithuania, or the King of Lithuania and of Russians. He ruled in the years 1316-1341. Gediminas was lauded as one of the greatest rulers of Lithuania. He established diplomatic and economic links with Europe and invited many artisans and merchants to Lithuania. His reign was marked with tolerance, open-mindedness and fairness.

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

Sat, 14th July, 2012 - (1) Comment

NEW VIDEOS:

Cold War eyewitnesses

come forward

Eyewitnesses at the Lithuanian Parliament in Janaury 1991.

Photo by Albinas Kentra.

The main objective of the new BALTIC INITIATIVE and NETWORK is to strengthen mutual understanding between the countries around the Baltic Sea through an exchange of information on the Cold War period. The idea is that history should be told from the historically valuable sites at which events took place. Relevant sites include, for example: military installations and towns, prisons and prison camps, partisan bunkers, execution sites, secret police offices, sculptures and architecture or simple squares or buildings where memorable events took place.

While this information is normally handled by museums, they believe that recent history can be told effectively from these sites from the prospective of – it happened here - with the significant help of eye witnesses.

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

Sat, 7th July, 2012 - (0) Comment

Timothy Snyder, author of Bloodlands: Europe between Hitler and Stalin:

Perhaps we can find

ways to talk to each other

A rough definition of Snyder's "Bloodlands" (by Timothy Nunan).

By Ellen Cassedy

“Even if all you want to do is understand your own group, you have no choice but to understand the history of others.”

That’s what Timothy Snyder, a professor at Yale University and the author of Bloodlands: Europe between Hitler and Stalin (Basic Books, 2010), had to say at a recent roundtable at the Tolerance Center in Vilnius.

I watched a webcast of the session – and welcomed the opportunity to revisit Snyder’s book, which I’d found challenging on two accounts.

First, immersing myself in the atrocities of the mid-20th century was no easy task. Between 1933 and 1945, in the region Snyder dubs the bloodlands – the Baltics, Belarus, most of Poland, Western Russia, and Ukraine – an unprecedented 16 million people were killed.

Second, Bloodlands required me to consider, simultaneously, the fate not only of my own group, as Snyder puts it, but also the history of others. That wasn’t easy either.

Timothy Snyder

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

200 years since Napoleon arrived in Lithuania

Wed, 27th June, 2012 - (0) Comment

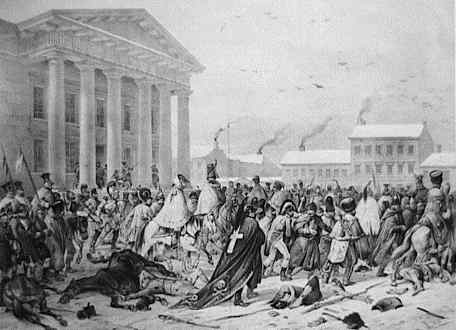

French Army in the Town Hall Square of Vilnius, Lithuania, 1812

By Jonas Damelis (1780—1840), a neoclassicist artist

associated with the School of Art at Vilnius University

By Vytautas J. Šliūpas

Two hundred years ago – on June 24, 1812, the French Grande Armée, led by Emperor Napoleon Boneparte, crossed the Nemunas River near Kaunas and invaded Czar Alexander I's Russia. I will not attempt to delineate the historical facts that are well known, but will present several episodes which deal with Lithuania and Lithuanians. Readers may be interested to know these facts, because Napoleon's first and last steps of the Russian campaign were taken in Lithuania.

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

Wed, 27th June, 2012 - (0) Comment

Vilnius – the city built

on human bones

Remains of a Grand Armée Soldier buried in Vilnius.

The skull of a Napoleonic soldier, who died during the French army's

1812 retreat from Moscow, discovered on a Vilnius construction site.

Picture: AFP/CNRS/Universite de la Mediterranee/Pascal Adalian

Vilnius, venerable capital of Lithuania, is sometimes called 'the city built on human bones'. It stands in the main Berlin to Moscow corridor, which for over 200 years has been the battlefields of the armies of Napoleon, the Tsars of Russia, Hitler and Stalin, as well as Poles and Prussians - hence its sinister description.

Early in 2002, while bulldozing some ugly Soviet barracks on the outskirts of Vilnius, municipal workers uncovered a mass grave. Thousands of skeletons were discovered there, laid out neatly in layers. Where did these bones come from? Were they those of Jews, massacred by the Nazis? No. For here's a metal button, with '61' stamped on it. Here's another, stamped '29'. And here's a patch of an ancient uniform, once blue. Also to be seen is a gold 20-franc coin from Napoleonic times, and a 'shako' (a French infantryman's helmet), squashed flat.

The drivers of the bulldozers stopped in their work. This was news - archaeological news - and these were the remains of some of the men that Napoleon had led into Russia in his pursuit of world supremacy in 1812.

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

Sat, 21st April, 2012 - (1) Comment

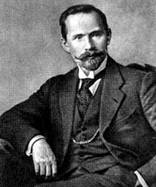

Antanas Smetona

Lithuania's famous

president who ended

his days in the U.S.

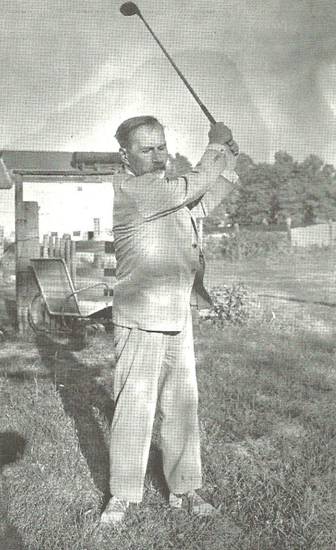

Antanas Smetona golfing in Michigan at the Tabor Farm after he came to the U.S. in 1941, escaping from the Soviet invasion of Lithuania in June 1940 |

||

|

Antanas Smetona (August 10, 1874 – January 9, 1944) was the most important Lithuanian political figure between World War I and World War II. He served as the first President of Lithuania from April 4, 1919 to June 19, 1920. He again served as the last President of the country from December 19, 1926 to June 15, 1940, before its occupation by the Soviet Union. He was also one of the famous ideologists of nationalism in Lithuania.

Lithuania was occupied by Soviet troops in 1940. After the USSR presented an ultimatum to Lithuania in June of that year, Smetona proposed armed resistance against the Soviets. The majority of the government and the commanders of the army did not concur with this proposal, and Smetona turned over the duties of President to Prime Minister Antanas Merkys, and on June 15 he and his family fled to Germany, and then on to Switzerland without surrendering his powers.

In 1941, Smetona emigrated to the United States, and lived in Pittsburgh and Chicago before settling in Cleveland, Ohio in May 1942 with his son Julius' family. While in exile, he began work on a history of Lithuania and on his memoirs. Smetona died in a fire at his son's house in Cleveland, on January 9, 1944, and was buried there. His wife Sofija died in Cleveland, on December 28, 1968, and he also had a daughter, Birutė.

In 1975, his remains were moved from Cleveland's Knollwood Cemetery mausoleum to All Souls Cemetery in Chardon, Ohio.

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

No flowers for Smetona

Sat, 21st April, 2012 - (13) Comment

Ohio crypt holds remains of first Lithuanian President,

yet he has been forgotten here in a Mausoleum tucked

away in a Catholic Cemetery east of Cleveland, USA.

By Frank Passic

There are no flowers at his crypt, although the Mausoleum is filled with them on the vaults of others nearby. He was the President, yet you would not know that by reading the simple inscription found upon his nameplate. His image was on a coin, a banknote, various stamps and medals. Yet he has been forgotten here in a Mausoleum tucked away in a Catholic Cemetery east of Cleveland, Ohio, USA.

His body has already been moved once since his death. But his remains haven’t been taken back to Lithuania since Lithuanian independence was restored, unlike the remains of his counterpart, President Kazys Grinius’ were. So his remains lay here in Ohio, far away from the country he loved and served.

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

Lithuania’s history has gone from glory to painful defeats

Sun, 12th February, 2012 - (2) Comment

PICTURE: The castles and the town of Kernave (R. Sidrys). Kernavė is a unique 5 mounds complex, honoured as being the first capital of Lithuania. The first settlers appeared here as early as in 9th-8th millennium BC, in the Epipaleolithic period. Since then until the very Early Middle Ages, the territory was continuously settled by people who left their traces. In written sources Kernavė was first mentioned in 1279 in the Livonian Chronicle and the Herman Vartberg Chronicle, where it was described as Traidenis’, the Great Duke’s of Lithuania, estate (1269-1282). At that time Kernavė was the most significant economic-political centre of Lithuania. In 1390 Kernavė was burnt in an attack by Crusaders. After the fire the wooden town and castles have never been rebuilt.

PICTURE: The castles and the town of Kernave (R. Sidrys). Kernavė is a unique 5 mounds complex, honoured as being the first capital of Lithuania. The first settlers appeared here as early as in 9th-8th millennium BC, in the Epipaleolithic period. Since then until the very Early Middle Ages, the territory was continuously settled by people who left their traces. In written sources Kernavė was first mentioned in 1279 in the Livonian Chronicle and the Herman Vartberg Chronicle, where it was described as Traidenis’, the Great Duke’s of Lithuania, estate (1269-1282). At that time Kernavė was the most significant economic-political centre of Lithuania. In 1390 Kernavė was burnt in an attack by Crusaders. After the fire the wooden town and castles have never been rebuilt.

The first people settled in the territory of Lithuania after the last glacial period in the 10th millennium BC. Over a millennium, the Proto-Indo-Europeans, who arrived in the 3rd – 2nd millennium BC, mixed with the local population and formed various Baltic tribes. The first written mention of Lithuania is found in a medieval German manuscript, the Annals of Quedlinburg, on 14 February 1009.

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

Sun, 12th February, 2012 - (0) Comment

A brief chronology

2000 B.C. Lithuanian ancestors settle along the Baltic coast.

1009 A.D. Lithuania is first mentioned in chronicles. Lithuanians already have a reputation as fierce warriors.

1200 While much of Europe has already converted to Christianity, Lithuania is still pagan and will remain so for several hundred more years. Lithuanians believed fire embodies the divine. A sacred flameis kept at a Vilnius temple tended to by vestal virgins. If they break their vows of chastity or the flame goes out, the penalty is death.

1236 Lithuania is united by Mindaugas and later crowned king. Unification helps Lithuania fend off German crusaders.

1323 Vilnius founded by Grand Duke Gediminas.

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

A world superpower for 300 years

Sun, 12th February, 2012 - (7) Comment

Grand Duchy of Lithuania, year 1500

“Lithuania was a superpower much longer than USA has been“. This is how I often tease my American friends arriving in Vilnius. But the teasing is in fact not so far away from reality, as the Grand Duchy of Lithuania (GDL) for 300 years was one of the leading and largest nations of the World – most probably Europe’s by then largest nation – stretching from the Baltic Sea to the Black Sea.

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

Thu, 2nd February, 2012 - (2) Comment

The Polish-Lithuanian

War 1919-1920

A series of articles in 4 parts

By Vincas Karnila, Associate editor

vin.karnila@VilNews.com

South-eastern Lithuania, Vilnius included, was occupied by Poland during the interwar period.

Picture: Celebration of the incorporation of Vilnius Region to Poland, 1922.

The Polish–Lithuanian War was an armed conflict between Lithuania and Poland in the aftermath of World War I and Lithuania's declaration of independence 16 February 1918.

The conflict primarily concerned territorial control of the Vilnius Region, including Vilnius, and the Suwałki Region, including the towns of Suwałki, Augustów, and Sejny. According to Lithuanian historians, the war was part of the Lithuanian Wars of Independence and spanned from spring 1919 to November 1920. According to Poland, the war included only fighting over the Suwałki Region in September–October 1920 and was part of the Polish–Soviet War.

After Vilnius was occupied by the Russian Bolsheviks in 1919, the government of the Republic of Lithuania established its main base in Kaunas. When Vilnius was forcibly annexed by Poland, Kaunas became the temporary capital of Lithuania, a position it held until 28 October 1939, when the Red Army handed Vilnius back to Lithuania. The Constituent Assembly of Lithuania first met in Kaunas on 15 May 1920. There were no diplomatic relations between Poland and Lithuania until 1938.

|

Part 1 – THE BUILD UP World War I ended on November 11, 1918 when Germany signed the Compiègne Armistice. On November 13, Soviet Russia renounced the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk. Most of today's Poland, Belarus, Ukraine and the Baltic States were passed to the government of Germany, which in turn decided to grant these states limited independence as buffer states) and began the Soviet westward offensive of 1918–1919. |

|

Part 2 – ADVANCES and RETREATS In April 1920 Poland launched the large-scale Kiev Offensive in hopes to capture Ukraine. Initially successful, the Polish Army started retreating after Russian counterattacks in early June 1920. Soon the Soviet forces began to threaten Poland's independence as they reached and crossed the Polish borders. |

|

Part 3 – STRUGGLES for the VILNIUS REGION Polish chief of state Jozef Pilsudski ordered his subordinate, General Lucjan Zeligowski, to stage a mutiny with his 1st Lithuanian–Belarusian Division (16 battalions with 14,000 soldiers) in Lida and capture Vilnius in fait accompli. |

|

Part 4 – THE AFTERMATH In March 1921, the plans for a referendum vote were abandoned. Neither Lithuania, which was afraid of a negative result, nor Poland, which saw no reason to change status quo, wanted it. The parties could not agree in which territory to carry out the vote and how Żeligowski's forces should be replaced by the League's forces. The League of Nations then moved on from trying to solve the narrow territorial dispute in the Vilnius Region to shaping the fundamental relationship between Poland and Lithuania. |

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

The Lithuanian Soviet Socialist Republic

Thu, 29th December, 2011 - (2) Comment

Flag of Lithuanian SSR.

The Lithuanian Soviet Socialist Republic (Lithuanian: Lietuvos Tarybų Socialistinė Respublika; Russian: Литовская Советская Социалистическая Республика, Litovskaya Sovetskaya Sotsialisticheskaya Respublika), also known as the Lithuanian SSR, was one of the republics that made up the former Soviet Union. Established on 21 July 1940 as a puppet state during World War II in the territory of the previously independent Republic of Lithuania after it had been occupied by the Soviet army on 16 June 1940 in conformity with the terms of 23 August 1939 Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, it existed until 1990.

Video: National anthem of Lithuanian SSR

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

Thu, 29th December, 2011 - (0) Comment

How did communism influence Lithuania’s economic development?

A report by: Valdas Samonis

The Institute for New Economic Thinking, USA

Photo: http://www.landesa.org/where-we-work/more/lithuania/

In 1940, independent Lithuania produced per capita 1.9 times more meat, 2.8 times more milk, had 1.9 times more cattle and 2.7 times more pigs than Soviet Union. After 50 years of allegedly astounding economic progress, Soviet Lithuania had become dependent on subsidies from Moscow. To the extent that this assertion is true, how is this possible if not for the inefficiencies caused by the forcefully imposed system of central planning with its associated distortions?

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

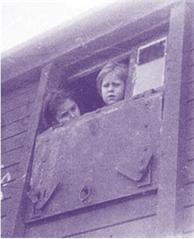

The tragic story of how one third of Lithuania’s population became victims of Soviet terror

Tue, 27th December, 2011 - (3) Comment

Dalia Kuodyte.

This article is based on a speech manuscript by Dalia Kuodyte, Member of the Parliament, former Director General of the Centre of Genocide and Resistance (LGGRTC).

“In the trains’ cattle cars the passengers were hardly given any food except from a little water and some inedible soup. There was scarcely any air to breathe as everyone was jammed together and the cars had only a few small windows covered with bars. A hole in the floor served as a toilet. Some of the people, especially the infants became sick immediately and died. The bodies of those who died on the journey were left on the side of the tracks.”

The string of tragedies began in August 1939, when Hitler and Stalin concluded a cynical agreement that divided up Central Europe between the two totalitarian countries. According to the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact, Lithuania was to fall into the Soviet zone of influence.

After the outbreak of the Second World War, Lithuania was occupied three times: first by the USSR in 1940, then by Nazi Germany in 1941, and finally by the USSR again in 1944.

Pre-war Lithuania’s position of neutrality on the eve of WWII did not protect the country from its sad fate. According to Lithuanian state institutions, the damage caused by the USSR‘s occupation to the Republic of Lithuania in financial terms is $278 billion. During Nazi and Soviet occupations, including 200,000 Holocaust victims, the losses of the population of Lithuania amounted to 33 percent of the total number of the country's population in 1940. Lithuania lost 1 million people to deportations, executions, incarceration, the murder of the political opposition and forced emigration.

The total number of persons registered as “anti-Soviet elements” reached 320,000 entries. There were teachers and professors, school and college students, farmers, industry workers and craftsmen among them.

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

Thu, 22nd December, 2011 - (2) Comment

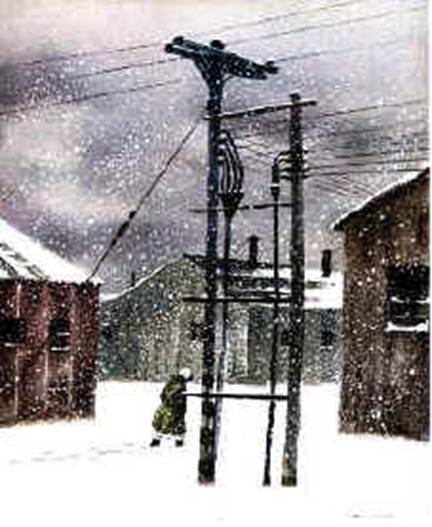

CHRISTMAS IN SIBERIA

A story about a Lithuanian family

deported to the Lena River delta.

North Siberia, year 1942

Text: Leona T. Gustaff

“The tents were freezing cold, harsh, and distressing; so, the adults decided to build better living conditions. "We can build barracks," said one Lithuanian, "We can catch the logs in the Lena River." The men waded barefoot into the icy water, caught floating logs, brought them to shore, and built the barracks. They covered the outside walls with snow and ice which they learned would help keep out the frigid temperature. They also found a large iron stove, which they placed in the middle of the building.”

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

VilNews e-magazine is published in Vilnius, Lithuania. Editor-in-Chief: Mr. Aage Myhre. Inquires to the editors: editor@VilNews.com.

Code of Ethics: See Section 2 – about VilNews. VilNews is not responsible for content on external links/web pages.

HOW TO ADVERTISE IN VILNEWS.

All content is copyrighted © 2011. UAB ‘VilNews’.

Click on the buttons to open and read each of VilNews' 18 sub-sections

Click on the buttons to open and read each of VilNews' 18 sub-sections