THE VOICE OF INTERNATIONAL LITHUANIA

|

VilNews has its own Google archive! Type a word in the above search box to find any article.

You can also follow us on Facebook. We have two different pages. Click to open and join.

|

Archive for 2011

- Posted by - (1) Comment

How I came to Lithuania 21 years ago (1 of 6)

Some private memories by Aage Myhre, VilNews Editor-in-Chief

aage.myhre@VilNews.com

Summer of 1990:

Landsbergis to Norway

In the summer of 1990 it’s still little known in the west that there once was a country called Lithuania. The fact that this small nation, with its two Baltic neighbours, are engaged in a process of secession from the Soviet Union has still not achieved any major headlines in our western newspapers. The fall of the Berlin Wall is more important. We do not know that the Soviet President, Mikhail Gorbachev, has recently been in Lithuania to meet the country's Communist leader, Algirdas Brazauskas (both pictured left). The fact that Lithuania's prime minister, Kazimir Prunskiene (centre above), has recently been in Norway to try to get the oil company STATOIL to deliver oil to the country, which is now subjected to blockade by the Soviet power, has been heard little about. Then Parliament President Vytautas Landsbergis (pictured right) comes on his first 'official visit' to a Western country, to Norway. That changes a lot.

A young man with a ponytail enters our office community in the centre of Oslo, Norway. It’s a warm, sunny day, mid-summer 1990. Someone has told him that our office, with 16 different small firms, enjoys a relatively large network of contacts, lobbyists perhaps although I do not know much about what that word means. He tells us that he is adviser to a president of a country we have hardly heard of before now. The country is called Lithuania, the president Vytautas Landsbergis, he informs us. The advisor’s name appears to be Ramunas Bogdanas.

What we get to know, is that Landsbergis needs help in finding contacts at the highest Norwegian level in connection with his planned 'official visit' to Norway in late August, the first for a Western country. Bogdanas asks us to undertake such a task. Even if he cannot offer any payment for the job.

We wonder why this Landsbergis has chosen precisely Norway as the first western country to visit on a so-called official basis. Would not the close-lying Sweden have been more obvious? "Sweden accepted the Soviet occupation and annexation of our country during World War II. As early as 1946. Norway never did. Formally, your country still considers Lithuania an independent nation. Therefore he has chosen Norway", explains Bogdanas.

Three of us in the business community sit down to discuss whether we want to accept the proposed mission, Dag Andersen, Bjorn Kittilsen and me. We agree to seek financial support before we answer Bogdanas. We make some calls to Statoil, the Telecom, Oslo Municipality and others. Oddly enough the answers are generally positive, and soon we start with the project. We call ourselves 'Lithuania Norway Corporation'.

Soon we convince our Prime Minister Jan P. Syse, Foreign Minister Kjell M. Bondevik and other leading politicians to give a warm welcome to Landsbergis when he and his delegation arrive. The period of the visit is 29 - 31 August 1990.

For Landsbergis the visit becomes the start of his long, strong relations with Norway. We are all very impressed with his knowledge of Edvard Grieg and Henrik Ibsen. Vytautas Landsbergis is a professor of music and an eminent pianist. In addition to being a politician.

We also introduce him and his delegation to Norwegian leaders in business and culture, and he is among those who get the honour of standing on the balcony of the National Theatre at the opening of our very first Ibsen Festival, along with our Norwegian cultural elite.

The visit becomes a great success. We who helped him are invited to Lithuania.

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - (0) Comment

How I came to Lithuania 21 years ago (2 of 6)

Some private memories by Aage Myhre, VilNews Editor-in-Chief

aage.myhre@VilNews.com

November 1990: A

Volga journey from Riga

November 1990: Delivery of coal to properties in Pilies g. right in the centre of Vilnius. With horses. People pick it up in burlap sacks. Other times, the horse driver is simply shovelling the coal out on the sidewalk in front of the buildings on the ordering list.

Photo: Aage Myhre.

We land at Riga airport on a late November afternoon in 1990. Flights from western countries are still not allowed to land in Vilnius. A white Volga from the Lithuanian government is waiting for us. The driver is 70. So is the speed (km/h), so it takes us seven hours to be driven the 300 kilometres from Riga to Vilnius. Through Baltic darkness.

We are two Norwegians bumping through Latvia and Lithuania this November evening in a poorly padded back seat. The car has certainly springs and shock absorbers, but they don’t help much. Through Latvia and the northern part of Lithuania the roads are like roads in Norway, narrow and winding. Great is therefore my surprise when half the distance remains and a four-lane highway appears in a country I had expected would only be characterized by worn out poverty! But the top speed of the Volga remains the same.

Almost seven hours have passed when we pass a huge sign. VILNIUS it says, in enormous concrete letters. But it is still dark outside the car windows. Only when we drive down the hill towards the centre, we begin to see some faint lights. Even one neon light. 'Hotel Lietuva' it says. On top of what we understand must be a very tall building. But the darkness dominates entirely. The feeling of the Soviet Union.

"It is better to light a small candle than to curse the darkness." I come to think of words of the Chinese philosopher Confucius (K'ung Fu-tzu). This becomes my motto for my further works in and with Lithuania.

To read more, go to our SECTION 13 – THE WORLD IN LITHUANIA

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - (3) Comment

How I came to Lithuania 21 years ago (2 of 6)

Some private memories by Aage Myhre, VilNews Editor-in-Chief

aage.myhre@VilNews.com

November 1990:

A Volga journey from Riga

November 1990: Delivery of coal to properties in Pilies g. right in the centre of Vilnius. With horses. People pick it up in burlap sacks. Other times, the horse driver is simply shovelling the coal out on the sidewalk in front of the buildings on the ordering list.

Photo: Aage Myhre.

We land at Riga airport on a late November afternoon in 1990. Flights from western countries are still not allowed to land in Vilnius. A white Volga from the Lithuanian government is waiting for us. The driver is 70. So is the speed (km/h), so it takes us seven hours to be driven the 300 kilometres from Riga to Vilnius. Through Baltic darkness.

We are two Norwegians bumping through Latvia and Lithuania this November evening in a poorly padded back seat. The car has certainly springs and shock absorbers, but they don’t help much. Through Latvia and the northern part of Lithuania the roads are like roads in Norway, narrow and winding. Great is therefore my surprise when half the distance remains and a four-lane highway appears in a country I had expected would only be characterized by worn out poverty! But the top speed of the Volga remains the same.

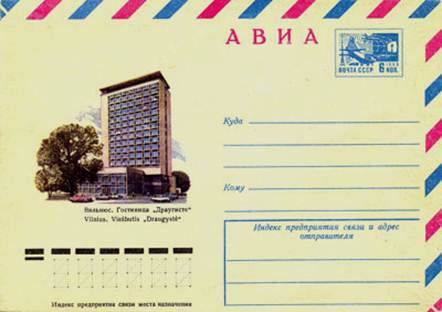

Almost seven hours have passed when we pass a huge sign. VILNIUS it says, in enormous concrete letters. But it is still dark outside the car windows. Only when we drive down the hill towards the centre, we begin to see some faint lights. Even one neon light. 'Hotel Lietuva' it says. On top of what we understand must be a very tall building. But the darkness dominates entirely. The feeling of the Soviet Union.

"It is better to light a small candle than to curse the darkness." I come to think of words of the Chinese philosopher Confucius (K'ung Fu-tzu). This becomes my motto for my further works in and with Lithuania.

It is well past midnight when we finally arrive at the hotel. Hotel Draugyste (friendship), where state guests, the ‘stately’ guests, are placed in safe environments. With microphones everywhere.

|

|

|

The hotel's dining options are obviously closed at this time of day. We ask if they have room service or whether there are open restaurants to find in the neighbourhood. Stupid question obviously. We can see the facial expressions of the two cute girls behind the huge long reception desk. They shake their heads. Then one of them remembers that there is an open door behind the reception, to the hotel’s coffee shop. Maybe there is some food left there after the day’s business hours. We jump over the counter. It’s the only way to get in.

The armed guard, who so far has been sitting quietly in one of the deep lobby lounge chairs made of not-so-genuine leather, pops up and starts to object strenuously. Fortunately, only with his mouth. The girls manage to restrain him, and soon we are in full swing enjoying our feast. Half sandwiches of dark bread. With three kinds of cold cuts: cheese, sausage and dried sardines. The girls are even finding a few bottles of warm beer for us.

The beds appear to be the too short. But we are too tired to react.

|

|

Next morning we go for a walk in the Old Town. Before the official programme starts. What we find is a beautiful but dilapidated city. The façades are mostly unpainted. Plaster has fallen off. The very few shops have no colourful shop windows. It smells of terrible Soviet fuel from Ladas, which dominates the city traffic. Horses with the carriages are moving around bringing out coal and more to people. Time seems to have stood still here. People are dressed in grey or other dark colours. Women wearing headscarves or hats, men often with berets tilted towards one ear. No smiles. We, with our Western clothing, must be a very unusual sight for them. But nobody is watching us. They look down or away. I feel sadness. |

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

Brand new apartments in Vilnius Old Town!

- Posted by - (0) Comment

Kotrynos vartai is being built at Klaipedos Street in the very centre of Vilnius Old Town, close to the St. Catherine Church and the Teachers‘ House.

Illustration: Resolution/NEWSEC.

It is not often build new homes here in Vilnius Old Town. There are simply very few vacant spaces. The financial crisis has also contributed to 'freeze' the majority of new developments in Lithuania’s real estate sector.

But now it's finally something happening. A brand new apartment complex under construction in the heart of the Old Town, on a site that until recently was reserved for old garages from the Soviet era.

Kotrynos Vartai is the name, a complex of apartments and two commercial premises being built at Klaipedos street next to St. Catherine’s Church and the Teachers’ House.

The development includes:

- 33 apartments from 28 to 138 sq.m;

- The smallest units are 1-room studios, the largest spacey 5-rooms apartments (4 bedrooms);

- Two commercial premises facing Klaipedos street;

- Underground parking;

- Most of the apartments are equipped with terraces, balconies, high ceilings and fireplaces;

- Two closed green inner yards, with playgrounds.

The construction works started spring 2011, Completion in autumn of 2012.

The apartments are sold at prices varying from 6.700 LTL/sq.m to 8.900 LTL/sq.m. Till now eight apartments are sold.

More information at www.kotrynosvartai.lt.

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

Brand new apartments in Vilnius Old Town!

- Posted by - (8) Comment

Kotrynos vartai is being built at Klaipedos Street in the very centre of Vilnius Old Town, close to the St. Catherine Church and the Teachers‘ House.

Illustration: Resolution/NEWSEC.

It is not often build new homes here in Vilnius Old Town. There are simply very few vacant spaces. The financial crisis has also contributed to 'freeze' the majority of new developments in Lithuania’s real estate sector.

But now it's finally something happening. A brand new apartment complex under construction in the heart of the Old Town, on a site that until recently was reserved for old garages from the Soviet era.

Kotrynos Vartai is the name, a complex of apartments and two commercial premises being built at Klaipedos street next to St. Catherine’s Church and the Teachers’ House.

The development includes:

- 33 apartments from 28 to 138 sq.m;

- The smallest units are 1-room studios, the largest spacey 5-rooms apartments (4 bedrooms);

- Two commercial premises facing Klaipedos street;

- Underground parking;

- Most of the apartments are equipped with terraces, balconies, high ceilings and fireplaces;

- Two closed green inner yards, with playgrounds.

The construction works started spring 2011, Completion in autumn of 2012.

The apartments are sold at prices varying from 6.700 LTL/sq.m to 8.900 LTL/sq.m. Till now eight apartments are sold.

More information at www.kotrynosvartai.lt.

Kotrynos vartai will be a truly green and attractive oasis in the very centre of the city.

Illustration: Resolution/NEWSEC.

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - (0) Comment

Vilnius Old Town is

unique in the world

Dominikonu Street in Vilnius Old Town. The colours play together. The

attention to detail is great.

Photo: Aage Myhre.

Text: Aage Myhre, architect and editor.

From an architectural point of view, the Vilnius Old Town is unique. In the world. It can also be justified to call this the world's most international city, taking into account all nations and cultures that have been involved in its planning and construction over many centuries.

It was here architects and builders from Italy and other Mediterranean countries came to shape the international Vilnius almost 700 years ago, along with experts from Central Europe. The influence of the city's large Jewish community was also very evident throughout the centuries.

It is to Vilnius you should come if you want to watch an entire people's ancient spirit, expressed in a beautiful, special setting unmatched anywhere else. It is when you walk around in the streets here that you will understand why Vilnius has been named as the 'New Babylon', 'Jerusalem of the North', 'The world's most Italian city outside Italy' and 'The world's most baroque city north of the Alps'.

It's when you feel the round cobbles in the streets pushing up against your shoe soles that you can fully understand the concepts of multiculturalism and multi-nationalism, as you could find it in Old Vilnius.

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - (1) Comment

Vilnius Old Town is

unique in the world

Dominikonu Street in Vilnius Old Town. The colours play together. The

attention to detail is great.

Photo: Aage Myhre.

Text: Aage Myhre, architect and editor.

From an architectural point of view, the Vilnius Old Town is unique. In the world. It can also be justified to call this the world's most international city, taking into account all nations and cultures that have been involved in its planning and construction over many centuries.

It was here architects and builders from Italy and other Mediterranean countries came to shape the international Vilnius almost 700 years ago, along with experts from Central Europe. The influence of the city's large Jewish community was also very evident throughout the centuries.

It is to Vilnius you should come if you want to watch an entire people's ancient spirit, expressed in a beautiful, special setting unmatched anywhere else. It is when you walk around in the streets here that you will understand why Vilnius has been named as the 'New Babylon', 'Jerusalem of the North', 'The world's most Italian city outside Italy' and 'The world's most baroque city north of the Alps'.

It's when you feel the round cobbles in the streets pushing up against your shoe soles that you can fully understand the concepts of multiculturalism and multi-nationalism, as you could find it in Old Vilnius.

Architecture is a reflection of the level of development and maturity of any nation in the world. The architecture of Vilnius

Old Town tells us about the outstanding wisdom and multiculturalism that hallmarked this country for hundreds of years.

Vilnius architecture reflects European styles - Gothic, Renaissance, Baroque, Classicism, and more - because Lithuania's ancient leaders knew how to seek advice and expert assistance from outside. Simultaneously the city developed its own unique style.

Vilnius was, during the centuries following 1323, the year the city was founded, fully on a par with cities further west and south in Europe.

In the 1500s, Vilnius was one of Europe's three leading renaissance cities, on par with Florence and Milan.

But the styles represent only one side of it. Equally important was the fact that the contemporary leaders,

urban planners and architects followed holistic planning ideals.

The areas between the buildings were as important as the buildings themselves. Human dimensions and scale was the excellent ideal. That’s how the planners of those days paved the way for good, interactive human life and activity in Vilnius.

Therefore, also today, the old Vilnius is a good, lively and warm city to live in for people from many nations and cultures.

Capitals around the world have their special features and icons, often very important symbols of the countries they represent. Paris has the Eiffel Tower. London has its bridge. Rome has the Colosseum. Washington has the White House, Berlin has its Brandenburg Gate.

Vilnius has its wonderful Old Town that was once among the world's foremost symbols of tolerance and

peaceful coexistence and from many different nationalities and cultures. A city that exuded peace, harmony and 'good life'. A city that went ahead in humanity.

Things have changed, but the Old Town of Vilnius remains the same.

Vilnius Old Town is genuine! Here a fragment of the old city wall from the 1500s.

Photo: Aage Myhre.

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

Since their peak in December 2007 apartment prices in Vilnius have fallen by 39.1%

- Posted by - (0) Comment

Apartment prices in the main cities in the Baltics are stable with Tallinn showing a surge in prices and sales last month, according to the latest Ober-Haus Baltic Apartment Price Index.

After a 0.1% increase in August prices of apartment in Vilnius remained stable in September at €1,209 per square meter. It means that year on year prices has decreased by 2.4%.

Sales activity in the region’s housing market normally increases in autumn but there is no sign of that happening in September as no major changes in apartment prices were seen in any major Lithuanian city.

Since their peak in December 2007 apartment prices in Vilnius have fallen by 39.1%.

Read more:

http://www.propertywire.com/news/europe/baltic-poland-property-prices-201110195697.html

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - (0) Comment

How I came to Lithuania 21 years ago (1 of 6)

Some private memories by Aage Myhre, VilNews Editor-in-Chief

aage.myhre@VilNews.com

Summer of 1990:

Landsbergis to Norway

In the summer of 1990 it’s still little known in the west that there once was a country called Lithuania. The fact that this small nation, with its two Baltic neighbours, are engaged in a process of secession from the Soviet Union has still not achieved any major headlines in our western newspapers. The fall of the Berlin Wall is more important. We do not know that the Soviet President, Mikhail Gorbachev, has recently been in Lithuania to meet the country's Communist leader, Algirdas Brazauskas (both pictured left). The fact that Lithuania's prime minister, Kazimir Prunskiene (centre above), has recently been in Norway to try to get the oil company STATOIL to deliver oil to the country, which is now subjected to blockade by the Soviet power, has been heard little about. Then Parliament President Vytautas Landsbergis (pictured right) comes on his first 'official visit' to a Western country, to Norway. That changes a lot.

A young man with a ponytail enters our office community in the centre of Oslo, Norway. It’s a warm, sunny day, mid-summer 1990. Someone has told him that our office, with 16 different small firms, enjoys a relatively large network of contacts, lobbyists perhaps although I do not know much about what that word means. He tells us that he is adviser to a president of a country we have hardly heard of before now. The country is called Lithuania, the president Vytautas Landsbergis, he informs us. The advisor’s name appears to be Ramunas Bogdanas.

What we get to know, is that Landsbergis needs help in finding contacts at the highest Norwegian level in connection with his planned 'official visit' to Norway in late August, the first for a Western country. Bogdanas asks us to undertake such a task. Even if he cannot offer any payment for the job.

To read more, go to our SECTION 13 – THE WORLD IN LITHUANIA

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

Happy Mozart weekend!

- Posted by - (0) Comment

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - (0) Comment

Vilnius Airport:

53.7% increase in passenger traffic

Watch the air traffic over Lithuania.

Vilnius International Airport (VIA) ended this year’s aviation summer season with excellent results: passenger traffic in October grew by 53.7% compared to the same period last year. Passenger traffic of the second month of autumn reached the most successful results of the same period of activity of 2008.

“This year’s autumn brought very satisfactory results and this fact once again proves that Vilnius International Airport has been implementing a purposeful strategy and chose the right flight geography development”, Minister of Transport and Communications Eligijus Masiulis summarized the activity results of the VIA.

In October Vilnius International Airport provided services for 168.2 thousand passengers and performed 2477 flights the number of which grew by 18%. In October the most popular destinations included London, Frankfurt, Copenhagen, Helsinki, Milan and Dublin. Last month the highest number of passengers was serviced by airlines Lufthansa, Scandinavian airlines, Finnair, Wizzair, Ryanair and AirBaltic.

“Our aim for the aviation winter season is to maintain the growth rate of 30% developed during the summer season by ensuring the best result in the history of our activity”, said Director General of VIA Tomas Vaišvila.

The number of flights provided in the current flight schedule for the winter season grew by more than one third compared to the winter season last year. During the winter season of 2010–2011 VIA performed flights for 19 routes, while for the same period in 2011–2012 it has been planned to increase the number of regular flights routes up to 27.

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

![]()

Tokeh Beach in Sierra Leone.

Greetings to our VilNews readers in:

- Togo

- Belize

- Hawaii

- Mauritius

- Polynesia

- Guatemala

- Sierra Leone

- Cote d'Ivoire

- Burkina Faso

- Dominican Republic

- Saint Vincent & Grenadines

Our VilNews e-magazine has now readers in no less than 114 countries!

The above 11 locations are probably representing our most exotic readerships.

It would be interesting to hear from you who are reading VilNews under the sun, so why not send us an email with some information about yourself, your connections to Lithuania etc – from your deckchair in the cooling shade under the palm tree?

We somehow like this that Lithuania attracts interest from suntanned readers so far away from the motherland...

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

Pulling extraordinary minds & brains together for the purpose of ‘rescuing’ Lithuania

- Posted by - (0) Comment

|

I have been reading some of the most interesting articles since the VilNews launch. There was one, in particular, that touched and impressed me deeply, it was an Oxfordian view on Lithuania's education. However, what has impressed me the most is the fact that you have been able to pull extraordinary 'minds & brains' together from all over the world for the purpose of 'rescuing' Lithuania as a nation, and fundamentally improve its current practices with respect to economic and political justice, business practices, educational sustainability and resilience and much, much more. Just wanted to say one more time THANK YOU!!!

|

“What has impressed me the most is the fact that you have been able to pull extraordinary 'minds & brains' together from all over the world for the purpose of 'rescuing' Lithuania as a nation, and fundamentally improve its current practices with respect to economic and political justice, business practices, educational sustainability and resilience and much, much more.”

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

Pulling extraordinary minds & brains together for the purpose of ‘rescuing’ Lithuania

- Posted by - (6) Comment

|

I have been reading some of the most interesting articles since the VilNews launch. There was one, in particular, that touched and impressed me deeply, it was an Oxfordian view on Lithuania's education. However, what has impressed me the most is the fact that you have been able to pull extraordinary 'minds & brains' together from all over the world for the purpose of 'rescuing' Lithuania as a nation, and fundamentally improve its current practices with respect to economic and political justice, business practices, educational sustainability and resilience and much, much more. Just wanted to say one more time THANK YOU!!!

|

“What has impressed me the most is the fact that you have been able to pull extraordinary 'minds & brains' together from all over the world for the purpose of 'rescuing' Lithuania as a nation, and fundamentally improve its current practices with respect to economic and political justice, business practices, educational sustainability and resilience and much, much more.”

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

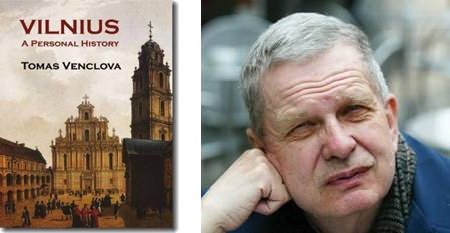

Vilnius University during “Soviet Times”

- Posted by - (0) Comment

Excerpt from Tomas Venclova’s book “Vilnius a Personal History”.

I entered the University shortly after Stalin’s death. I was sixteen years old, one of the youngest students there. Times had somewhat improved―become more “vegetarian,” to quote Anna Akhmatova. The war against the anti-Communist Lithuanian and Polish partisans was coming to an end, most of them having been killed. The deportations had stopped, and people―though not all, by far―were coming back from Siberia and the prisons. Yet grim Soviet conditions still prevailed. Polish professors from the prewar era had been ousted―“repatriated” was the official term―and there were scarcely any Lithuanian professors left. Some ended up in America, others in concentration camps or six feet under, and still others were simply not permitted to teach. In the best of cases, they were replaced by high school teachers (most of them very intimidated); in somewhat worse cases, by young careerists; and in the worst of all cases, by individuals who had sent dozens of people into slave labor. Among this third group were many recent arrivals from Russia, who were more successful than the locals in adapting to the system since they knew it better. Lithuanian continued to be the language of instruction. The local Communists thought this was to their great credit, but those in power probably weren’t especially interested in which language was used―what was more important to them was what was said. Marxism (oh, if only it had really been Marxism!) and military training took up almost all the students’ time. At least half of the university library could not be accessed without special permission, something that was practically impossible to get.

Go to our Section 18 to read more

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

Vilnius University during “Soviet Times”

- Posted by - (0) Comment

Excerpt from Tomas Venclova’s book “Vilnius a Personal History”.

I entered the University shortly after Stalin’s death. I was sixteen years old, one of the youngest students there. Times had somewhat improved―become more “vegetarian,” to quote Anna Akhmatova. The war against the anti-Communist Lithuanian and Polish partisans was coming to an end, most of them having been killed. The deportations had stopped, and people―though not all, by far―were coming back from Siberia and the prisons. Yet grim Soviet conditions still prevailed. Polish professors from the prewar era had been ousted―“repatriated” was the official term―and there were scarcely any Lithuanian professors left. Some ended up in America, others in concentration camps or six feet under, and still others were simply not permitted to teach. In the best of cases, they were replaced by high school teachers (most of them very intimidated); in somewhat worse cases, by young careerists; and in the worst of all cases, by individuals who had sent dozens of people into slave labor. Among this third group were many recent arrivals from Russia, who were more successful than the locals in adapting to the system since they knew it better. Lithuanian continued to be the language of instruction. The local Communists thought this was to their great credit, but those in power probably weren’t especially interested in which language was used―what was more important to them was what was said. Marxism (oh, if only it had really been Marxism!) and military training took up almost all the students’ time. At least half of the university library could not be accessed without special permission, something that was practically impossible to get.

Only the University buildings resisted the new times. They were dilapidated and full of garbage. The sewer system didn’t work, and paint and plaster were crumbling off the walls―but the huge labyrinth of inner courtyards, perhaps the most important feature of the Old City, remained. You could wander through this labyrinth for hours. Students joked that there were places where no man had ever set foot. And indeed there were some courtyards we could only see through the auditorium windows; it was a total puzzle how one could gain access to them. All the courtyards had been renamed, since the pre-war names recalled professors of the Jesuit era who, to say the least, seemed suspect to the Soviet authorities. (The Lithuanian nationalists didn’t like the Jesuits much either: although they may not have been Poles, they were cosmopolites.) But sooner or later, the old names turned up again, almost of their own accord. The most archaic courtyard and the one I knew best had a dry fountain with the trunk of a birch tree hanging over it. The southern wing of the courtyard, which had hardly changed since the days of the founding of the University, was supported by massive Gothic pillars. Other, more slender columns decorated an adjoining building; they lent the courtyard color, even cheerfulness, for the upper part was entirely clad in red brick. It was called the Courtyard of Philology, but we all knew that its real patron saint was Sarbievius, the seventeenth-century poet.

Poczobutt Courtyard, on the other hand, dated from a later era. It had an aura of mystery, its arcades usually fading into the dusky light. But the filigree pattern of shadows cast by bare tree branches fell on rough, sun-bathed, cylindrical little towers decorated with bas-reliefs of the signs of the zodiac. On the wall between the towers it was possible to make out Latin inscriptions. I memorized one of them, the hexameter verse, Addidit antiquo nova lumina coelo. Telescopes from the eighteenth century were preserved in the towers’ round rooms. This is where the Jesuit Martin Poczobutt built his observatory, and through these telescopes he observed Mercury, the comets, and the first asteroids. Once, according to his contemporaries, when he was trying to establish the precise orbit of the newly-discovered planet Uranus, he was so exhausted after several sleepless nights that he suffered a hemorrhage and thought he would die. He created a new constellation on the cosmological charts called “Poniatowski’s Bull” (Taurus Poniatovii) in honor of the last Polish-Lithuanian King. Poczobutt proudly carved it into the bas-relief among the other signs of the zodiac. From this courtyard, it is possible to go through a low archway and arrive at the largest and most beautiful courtyard, named in honor of Piotr Skarga, the University’s first rector. In contrast to Poczobutt Courtyard, which calls to mind a semi-dark, idyllic room, the Skarga Courtyard opens up like a wide Italian plaza surrounded on three sides by ochre elliptical arches, and bordered on the fourth by a remarkable façade shaped like an organ, with a massive, square bell tower rising to the right. It looks very southern, even when I’ve seen it during a blizzard. Some compare the plaza to San Marco in Venice.

The façade next to the bell tower is perhaps the consummate work of the architect Johann Christoph Glaubitz. Glaubitz blended it with the very large, old Gothic Church of St. John’s, built by Jogaila. The first school in Vilnius―and in all of Lithuania―was affiliated with it. The University was also established on this spot, which is so rich in tradition. Glaubitz’s façade is late Baroque and truly monumental, yet it seems to vanish into the air. Its colonade consists exclusively of arches and curves; groups of columns tied together by niches, volutes, curved cornices, and metal ornamentation spread out like a web. Silhouetted against the sky with curving, non-Euclidian arcs, the multi-story building becomes smaller toward the top, and its reliefs lighter. Neither solidity nor substantiality remains: architecture renounces itself here and enters the spheres of music and poetry. The kaleidoscopic composition of the ten altars inside the church is in the same style. Originally, there were twenty-two altars, but the most were destroyed in the first half of the nineteenth century; the sculptures and statues were reduced to rubble and carried off in three thousand wagons.

A second misfortune overtook the church after the Second World War. As a student, I couldn’t imagine―even in my wildest dreams―that I would be permitted to enter into the same space where theological issues had once been debated, and where later Mickiewicz and Daukantas attended Mass. With its windows smashed, its interior deserted, the church had been turned into a storeroom for paper―not for vodka, as was the case with St. Casimir’s. Later, the paper probably disappeared too. There was a rumor that some Soviet film outfit was using the church to make a war film, and several dozen live artillery shells were fired off inside the church. It wasn’t until the University’s anniversary that money was found for renovations. The church has only recently once again served as a place of worship.

It was these buildings that kept us from forgetting the very idea of civilization. I am describing only what first strikes one in the Latin quarter of Vilnius. There were countless other mysterious, remote corners: little interior courtyards with upper storeys and pilasters; statues atop old stairways; illegible inscriptions on cracked bas relief, where above windows one could make out medieval symbols. There were chambers preserved from the time of the Jesuits; on one ceiling there was a peaceful Madonna next to portraits of Democritus and Epicurus; Copernicus’s book De revolutionibus orbium coelestium was resplendently displayed in a vitrine―a copy that had allegedly been presented to the author on his deathbed. The ceiling arches of the auditoriums, the clumsy wooden benches on which generations of students left their marks with pens or pocket knives, were much more human than the lectures about the history of the Communist Party or seminars dealing with the history of Soviet literature.

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

VilNews e-magazine is published in Vilnius, Lithuania. Editor-in-Chief: Mr. Aage Myhre. Inquires to the editors: editor@VilNews.com.

Code of Ethics: See Section 2 – about VilNews. VilNews is not responsible for content on external links/web pages.

HOW TO ADVERTISE IN VILNEWS.

All content is copyrighted © 2011. UAB ‘VilNews’.

Click on the buttons to open and read each of VilNews' 18 sub-sections

Click on the buttons to open and read each of VilNews' 18 sub-sections

.jpg)