THE VOICE OF INTERNATIONAL LITHUANIA

|

VilNews has its own Google archive! Type a word in the above search box to find any article.

You can also follow us on Facebook. We have two different pages. Click to open and join.

|

Archive for April, 2012

Slideshow commemorating 50 seasons of Boston Lithuanian Cultural Saturday evenings (Subatvakaris) and 60 years of the National Lithuanian Society of America, Boston Chapter (Amerikos Lietuvių Tautinė Sąjunga (ALTS)). Background singing from the Vilnius University girls choir Virgo performing during the cultural part of the jubilee program, November 7, 2009, at the South Boston Lithuanian Citizens Association, 368 W. Broadway, South Boston, Massachusetts USA.

The slideshow includes pictures of events and the founders at the Boston Chapter's National Lithuanian Society House at 484 Fourth Street in South Boston, MA from the 1950's to 1980's. After selling the building, and a period of inactivity, the Subatvakaris cultural evenings were revived in the 2000's and are now held at the South Boston Lithuanian Citizens Association, 368 W. Broadway, South Boston, MA.

Draugas article (in Lithuanian), http://www.draugas.org/12-03-09boston.html

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

I find the whole issue of identity quite fascinating and something that is often underestimated or assumed

- Posted by - (1) Comment

![]()

I have been visiting your website and have enjoyed reading the various items. I think it is a very useful resource especially for people of Lithuanian background living outside Lithuania - as it gives them a chance to interact and hear opinions etc. from locals and others.

I like the interviews and the historical info the best - the banter and dialogue can be interesting too - but it can easily get dominated by a personality or two.

But it is a very great thing you are doing and I am very happy to see you seem to have a growing base of advertisers which suggests that the site can be self supporting and even flourish.

I find the whole issue of identity quite fascinating and something that is often underestimated or assumed ... but really is quite important and your site can certainly help to illuminate this issue for Lithuanians living both here and abroad.

Vytas PACAS

(LT-Canadian)

Vilnius

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - (0) Comment

Raised growth forecast for Lithuania but no switch to Euro until 2015

Estonia’s economy will probably expand 4.2 percent next year, compared with a January forecast of 4 percent, the bank said in an e-mailed report today. Latvia’s economy may grow 3.5 in 2013, while Lithuania’s gross domestic product may expand 4.3 percent, it said.

The bank also raised Latvia’s 2012 growth forecast to 2.5 percent from a previous estimate of 2 percent, the report said.

Swedbank also said Lithuanian chances to qualify for euro adoption as planned in 2014 have “significantly narrowed” because of consumer-price growth. The country is more likely to switch currencies in 2015, it said.

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - (0) Comment

Lithuania among the most attractive destinations for shared services and BPO

Former British Ambassador to Lithuania, Mr Simon Butt and Lithuanian Ambassador to the UK, Dr. Oskaras Jusys

Global Shared Services industry experts named Eastern and Central Europe as a most attractive destination for Shared Services (SS) and Business Process Outsourcing (BPO) for businesses that are looking to relocate their operations to more competitive locations.

Experts from the UK and the United States gathered to share views on current trends in the global shared service and BPO industry at a reception hosted by Invest Lithuania, at the new premises of the Lithuanian Embassy in London on April 17.

Associate Director and Corporate Location Consultant of Jones Lang LaSalle, Mr. Alex Ash noted that businesses are rebalancing their business services portfolios globally. Ms Cynthia Pasky, founder, president and CEO of Strategic Staffing Solutions (S3), highlighted that People, Price and Proximity are key criteria for relocating operations. She remarked that rising labour costs, retention, quality, and distance to client, both cultural and physical, have emerged as factors challenging Asia’s traditional advantages as a destination for relocating services centres.

Mr Adrian Hall, Strategic Lead at Barclays Bank PLC, noted that Barclays Bank initially planned in 2010 to recruit around 250 employees for its strategic IT engineering centre in Lithuania, but has since taken on some 700 IT professionals. He said Barclays is very satisfied with the great talent pool, cost-effectiveness and the geographical and cultural proximity of Lithuania to the UK.

The former British Ambassador to Lithuania, Mr Simon Butt and the Lithuanian Ambassador to the UK, Dr. Oskaras Jusys, agreed that with its highly skilled and multilingual talent, low operating costs, physical and cultural proximity to Western and Northern Europe, Eastern Europe is emerging as a strong competitor with Asia in terms of attracting Shared Service as well as BPO investments.

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

US-Lithuanian Facebook sites do a superb job!

- Posted by - (0) Comment

Visit: LT NEWS |

||

|

||

Visit: The Lithuanian Rat Pack |

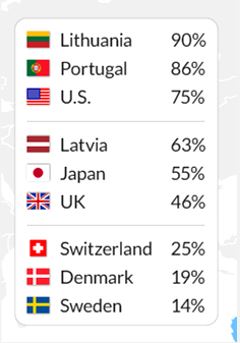

“In this new media age, there is a growing population interested in Lithuania and its culture. LTnews.net provides a simple, easy-to-access platform with a social media aspect that has re-shaped the way people can seek a topic of interest.”

This write the enthusiasts behind the site and the Facebook page LT NEWS in their introduction to the page. They represent one of many new social media in the United States with Lithuania as the main theme. Combined, these sites have revived a strong, energetic interest in the home country here at the southern shore of the Baltic Sea.

There are many, many more than the four we mentioned above, and there are similar sites in many other countries. Please contact us if you represent one of these sites, and we will eventually put together a more comprehensive overview and presentation here in VilNews.

Check out our SECTION 11

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

US-Lithuanian Facebook sites do a superb job!

- Posted by - (3) Comment

Visit: LT NEWS |

||

|

||

Visit: The Lithuanian Rat Pack |

“In this new media age, there is a growing population interested in Lithuania and its culture. LTnews.net provides a simple, easy-to-access platform with a social media aspect that has re-shaped the way people can seek a topic of interest.”

This write the enthusiasts behind the site and the Facebook page LT NEWS in their introduction to the page. They represent one of many new social media in the United States with Lithuania as the main theme. Combined, these sites have revived a strong, energetic interest in the home country here at the southern shore of the Baltic Sea.

There are many, many more than the four we mentioned above, and there are similar sites in many other countries. Please contact us if you represent one of these sites, and we will eventually put together a more comprehensive overview and presentation here in VilNews.

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

Linas Johansonas,

LTnews.net Editor-in-Chief

Linas Johansonas, chief editor of Ltnews, think we were too negative in our article about the tomb of President Smetona, where we used the title "No flowers for Smetona." Linas believes that the tomb is visited and honoured by many. To convince us of this, he invited me to Cleveland so I can see with my own eyes.

He also thinks there is more I should do while in Cleveland…

***

Aage, after you visit President Smetona's grave in Cleveland, make sure you visit Cleveland's historic Lithuanian Cultural Garden :)

Lithuanian Cultural Garden in Cleveland Ohio

The Lithuanian Cultural Garden was dedicated October 11, 1936.

Lithuanian Cultural Garden in Cleveland Ohio

www.clevelandpeople.com

Photos from the Lithuanian Cultural Garden in Cleveland Ohio - statues of Vincas Kudirka, Pillars of Gediminas, Jonas Basanavicius, Fountain of Biruta , Maironis

Checkout some of my photos from the LT garden in this photo album http://www.facebook.com/media/set/?set=a.1046292712242.2009191.1073375623&type=3

Lithuanians

Photos by: Linas Johansonas

By: Linas Johansonas

http://www.facebook.com/groups/52628882669/

Friends of the Lithuanian Cultural Garden of Cleveland

"One of Cleveland's Cultural Gardens, sponsored by its foreign born citizens. The Lithuanian Cultural Garden is laid out in the form of a huge lyre, which symbolizes the Lithuanians' love for music. The stone work depicts three stages of Lithuanian history. The bust in the center is that of Dr. Jonas Basanavicius, Lithuanian liberator."The Lithuanian Cultural Garden also features busts of Maironis (poet/writer) and Vincas Kudirka (author of Lithuania's national anthem), the Pillars of Gediminas (Gedimino Stulpas), and a fountain dedicated to Lithuania's Grand Duchess Birute.Dedicated in October 1936, the Lithuanian Cultural Garden extends from East Boulevard down three levels to Martin Luther King Boulevard. According to Clara Lederer, in Their Paths are Peace , the "original design was drawn up in Lithuania by Professor Dubinecras, and was modified to fit the boulevard topography by the City Plan Commission of Cleveland." The Lithuanian Cultural Garden’s choices of sculpture reflects how much questions of national identity played into the construction of many of the gardens. ~Dr.M.Tabeau

http://www.culturalgardens.org/federation.aspx

After you visit the LT Gardens, you can stop at the Lithuanian Club at the Lithuanian Community Center for a Svyturys…

http://www.facebook.com/media/set/?set=a.10150236615690337.344774.356431370336&type=3

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

During the first three months of this year the number of passengers at Vilnius International Airport on the average grew by 64.3 percent !

- Posted by - (0) Comment

![]()

During the first three months of this year the number of passengers at Vilnius International Airport (VIA) on the average grew by 64.3 percent. This March the VIA serviced 142 thousand passengers – 17.5 percent more than in February and as much as 56.5 percent more than in March 2011.

2277 flights were performed last month, which makes up for 8.5 percent increase compared to the same period last year. London, Frankfurt, Riga and Copenhagen were amongst the most popular destinations.

“The results of the first quarter set a good start for the aviation summer season which commenced 25 March. So far we can see that Vilnius International Airport growth plans are being successfully implemented. During the summer season as much as 5 new airlines will be operating on 11 new routes,” – Minister of Transport and Communications Eligijus Masiulis commented on the VIA performance.

Good performance is the result of successful operation of traditional airlines and growing demand in low-cost carriers’ services. One of the companies which serviced the largest number of passengers in March is Lufthansa. The airline celebrated its 20th anniversary at VIA and by offering two daily flights to Frankfurt serviced almost 13 thousand passengers per month. Scandinavian Airlines also demonstrated excellent results for March with 10.5 thousand passengers and helped to keep Copenhagen amongst the top destinations of Vilnius International Airport. Excellent results were demonstrated by the airline airBaltic which offered flights to Riga and serviced 12.5 thousand passengers.

Direct connection with Milan and London introduced last year proved to be highly successful – these destinations were chosen by 8 thousand and 16.5 thousand passengers, respectively. The popularity of these destinations contributed to the successful performance of low-cost carriers – in March WizzAir serviced 25.5 thousand passengers and Ryanair – almost 30 thousand passengers.

During the summer season Vilnius International Airport will offer flights to 31 cities and 36 airports. 40 direct regular flights shall be operated from Vilnius. 21 airlines shall be offering regular flights during the summer season.

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - (0) Comment

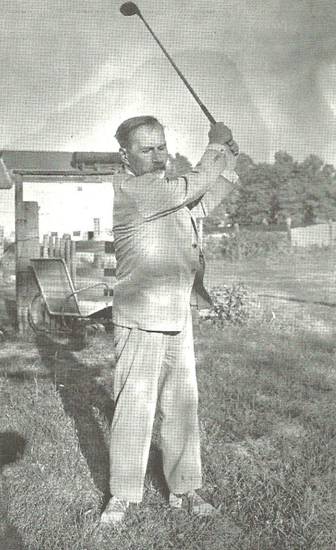

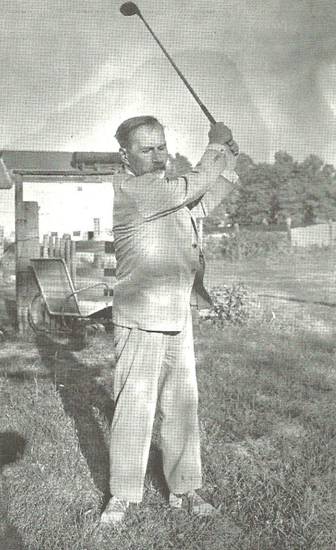

Antanas Smetona

Lithuania's famous

president who ended

his days in the U.S.

Antanas Smetona golfing in Michigan at the Tabor Farm after he came to the U.S. in 1941, escaping from the Soviet invasion of Lithuania in June 1940 |

||

|

Antanas Smetona (August 10, 1874 – January 9, 1944) was the most important Lithuanian political figure between World War I and World War II. He served as the first President of Lithuania from April 4, 1919 to June 19, 1920. He again served as the last President of the country from December 19, 1926 to June 15, 1940, before its occupation by the Soviet Union. He was also one of the famous ideologists of nationalism in Lithuania.

Lithuania was occupied by Soviet troops in 1940. After the USSR presented an ultimatum to Lithuania in June of that year, Smetona proposed armed resistance against the Soviets. The majority of the government and the commanders of the army did not concur with this proposal, and Smetona turned over the duties of President to Prime Minister Antanas Merkys, and on June 15 he and his family fled to Germany, and then on to Switzerland without surrendering his powers.

In 1941, Smetona emigrated to the United States, and lived in Pittsburgh and Chicago before settling in Cleveland, Ohio in May 1942 with his son Julius' family. While in exile, he began work on a history of Lithuania and on his memoirs. Smetona died in a fire at his son's house in Cleveland, on January 9, 1944, and was buried there. His wife Sofija died in Cleveland, on December 28, 1968, and he also had a daughter, Birutė.

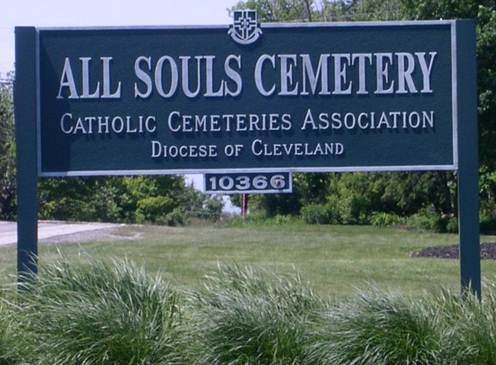

In 1975, his remains were moved from Cleveland's Knollwood Cemetery mausoleum to All Souls Cemetery in Chardon, Ohio.

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - (1) Comment

Antanas Smetona

Lithuania's famous

president who ended

his days in the U.S.

Antanas Smetona golfing in Michigan at the Tabor Farm after he came to the U.S. in 1941, escaping from the Soviet invasion of Lithuania in June 1940 |

||

|

Antanas Smetona (August 10, 1874 – January 9, 1944) was the most important Lithuanian political figure between World War I and World War II. He served as the first President of Lithuania from April 4, 1919 to June 19, 1920. He again served as the last President of the country from December 19, 1926 to June 15, 1940, before its occupation by the Soviet Union. He was also one of the famous ideologists of nationalism in Lithuania.

Lithuania was occupied by Soviet troops in 1940. After the USSR presented an ultimatum to Lithuania in June of that year, Smetona proposed armed resistance against the Soviets. The majority of the government and the commanders of the army did not concur with this proposal, and Smetona turned over the duties of President to Prime Minister Antanas Merkys, and on June 15 he and his family fled to Germany, and then on to Switzerland without surrendering his powers.

In 1941, Smetona emigrated to the United States, and lived in Pittsburgh and Chicago before settling in Cleveland, Ohio in May 1942 with his son Julius' family. While in exile, he began work on a history of Lithuania and on his memoirs. Smetona died in a fire at his son's house in Cleveland, on January 9, 1944, and was buried there. His wife Sofija died in Cleveland, on December 28, 1968, and he also had a daughter, Birutė.

In 1975, his remains were moved from Cleveland's Knollwood Cemetery mausoleum to All Souls Cemetery in Chardon, Ohio.

Early life

Born in the village of Užulėnis, Taujėnai rural district of Ukmergė district municipality, Antanas Smetona was sent to the primary school in Taujėnai. Graduating from the Palanga Pre-Gymnasium in 1893, he passed his entrance examinations into the Samogitian Diocesan Seminary in Kaunas, with thoughts of becoming a Catholic priest, but various circumstances soon thereafter changed these plans, and he enrolled at Jelgava Gymnasium (high school) in Latvia. Here, together with Jonas Jablonskis, Vincas Kudirka and others, he belonged to a secret Lithuanian students' organization. This organization was nationalistic, and anti-Czarist in nature. In the autumn of 1896, he organized the resistance of students against obligatory attendance of the Russian Orthodox Church, and was expelled from the Gymnasium, but was later allowed to study at the Gymnasium No.9, in Saint Petersburg.

After graduating from this Gymnasium in 1897, Smetona entered the Faculty of Law of the University of Saint Petersburg. He joined the activities of the secret Lithuanian Student Organization at the University, and was made its chairman. He became involved with the publishing and dissemination of Lithuanian books. On two occasions he faced the threat of being expelled from the University, and experienced being arrested and a short imprisonment. After his graduation from the University in 1902, he worked at the Agricultural Bank of Vilnius. Two years later he married Sofija Chodakauskaitė.

Early activities

From his very first days in Vilnius, Smetona became involved in the activities of various Lithuanian nationalist groups, and joined the Lithuanian Democratic Party, which he represented in the Great Seimas of Vilnius. He was later elected into its Presidium. In 1904 and 1907, he was on the staff of the Lithuanian newspapers, Vilniaus Žinios (The Vilnius News), and in 1905-1906, edited the weekly Lietuvos Ūkininkas (The Lithuanian Farmer). In 1907, Smetona and the Rev. Juozas Tumas-Vaižgantas established a venture to print the newspaper Viltis (The Hope), and started publishing and circulating it. In Viltis, Smetona advocated national unity; he was also one of the incorporators of the Aušra (Dawn) company for the publishing of Lithuanian books, a member of the Lithuanian Mutual Aid Society of Vilnius, the Lithuanian Learned Society, the Vilniaus aušra (The Dawn of Vilnius), and Rytas (The Morning) education societies, the Rūta Art Society and many other societies, taught the Lithuanian language at Vilnius schools. In 1914, he started publishing Vairas (The Rudder), a new bi-weekly magazine. Also he worked with the writer Liudvikas Jakavicius.

Politics

During the First World War, he was the 1st Vice-Chairman, and later Chairman, of the Central Committee of the Lithuanian Relief Society for helping victims of the war. In the summer of 1916, Antanas Smetona, together with other Lithuanians from Vilnius, presented a memorandum to the German Chief Commander of the Eastern Front, in which he demanded the right of the Lithuanian nation to have an independent State. On September 6, 1917 he started printing the newspaper Lietuvos Aidas (Lithuania's Echo), worked as its publisher and its editor-in-chief. In the first issue of the newspaper, Smetona wrote that the most important goal of the Lithuanian nation was the re-establishment of an independent Lithuanian state.

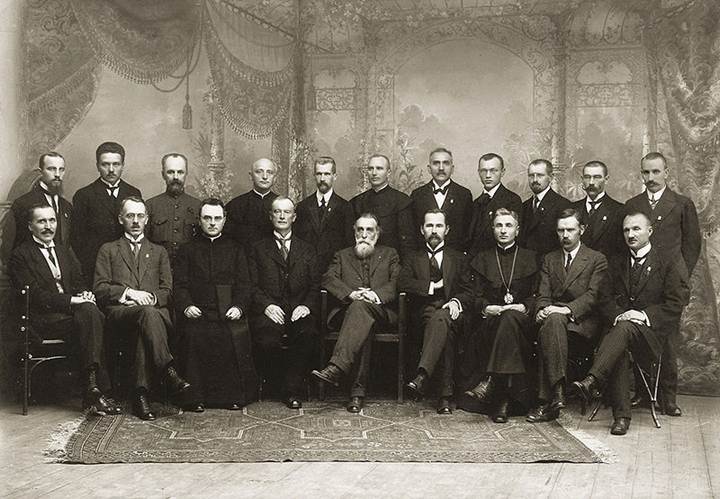

Between September 18 and 22, 1917, he participated in the Lithuanian Conference in Vilnius, and was elected Chairman (1917–1919), of the Council of Lithuania (later Council of the State). On February 16, 1918, Antanas Smetona signed the Act of Independence of Lithuania.

Smetona

(first right from centre) in the Council of Lithuania, February 16, 1918, the

day Lithuanian declared independence after more than hundred years of Tsarist

occupation.

Between December 1918 and March 1919, he lived primarily in Germany and the Scandinavian countries, soliciting loans for the cause of Lithuanian independence. On April 4, 1919, the State Council of Lithuania elected Smetona the first President of the Republic of Lithuania. On April 19, 1920, the Constituent Assembly elected Aleksandras Stulginskis President. Not re-elected to the Seimas, from 1921 throughout 1924 he edited several periodicals, as Lietuvos balsas ("Voice of the Lithuania"), Lietuviškas balsas ("Lithuanian Voice") and Vairas ("The Steering Wheel").

After the Klaipėda Revolt of January 1923, in the Memelland, which had been separated from Germany, he was made commissioner there on February 20, but due to disagreements with Prime Minister Ernestas Galvanauskas, he resigned from his post.

In November 1923, authorities imprisoned Smetona for several days for publishing an article by Augustinas Voldemaras, in Vairas. Between 1923 and 1927, he was an assistant Professor at the University of Lithuania - at first at the Chair of Art Theory and History and later at the department of Philosophy. He lectured on ethics, antique philosophy, and gave lectures on Lithuanian linguistics. In 1932, he was awarded an honorary Ph.D. at the Vytautas Magnus University.

Smetona participated in the activity of the Lithuanian Riflemen's Union that had staged the Klaipėda Revolt, which gave him greater name-recognition. More than once, he was elected to its central board. Between 1924 and 1940, he was the vice-Chairman of the Board of the International Bank, and one of the members of a number of societies and companies.

Authoritarian president

Antanas Smetona was one of the leaders of the coup d'état of 1926, which deposed President Kazys Grinius, and Smetona once again became President on December 19 of that year (two others briefly held the office during the coup, which began on December 17, before Smetona was formally restored to the Presidency.

See also our VilNews article https://vilnews.com/?p=3545, “The man who declined the Presidency.”

After the coup, Smetona designated Augustinas Voldemaras, as Prime Minister. One year later he suppressed the parliament, and on May 15, 1928, with the approval of the government, he promulgated a new Constitution of the Lithuanian State with more extensive presidential powers. In 1929, he removed Voldemaras and became authoritarian head of state. He was re-elected President in 1931 and 1938, and remained in office until June 15, 1940, when Lithuania was occupied by the Soviet Union.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Why President Smetona's wife smoked Russian cigarettes and refused to talk to Polish ambassador in their native tongue

By: Alfonsas Eidintas / 15min.lt

President Antanas Smetona

and his family: wife Sofija Smetonienė, son Julius, daughter

Marytė

Smetonaitė-Valušienė, and son-in-law Aloyzas Valušis

The following three articles are from VilNews’

collaborative e-publication http://www.15min.lt/en

Alfonsas Eidintas, historian and Lithuania's former ambassador to the USA, Canada, Mexico, Israel, and Norway, has recently published a second book on Lithuania's inter-war president Antanas Smetona. The book is called "Antanas Smetona and His Environment" and the author has kindly agreed to let 15min.lt share some of its chapters. The following is an extract from a chapter on Smetona's wife, Lithuania's first First Lady, Sofija Smetonienė.

Unlike her reserved husband Antanas Smetona, Sofija was talkative and full of energy, partial to good company, a woman of action and resolution. Chodkauskai, a noble family of Antanas Chodkauskas, Sofia's father, who married his cousin Marijona Chodkauskaitė, lived in Gavenonys estate (Šiauliai region) and used Polish among themselves, speaking Lithuanian to peasants only, yet Sofija had sympathized with the Lithuanian national movement from her early days.

Her father would invite Lithuanian students, recommended by the linguist Jonas Jablonskis, to teach his children. During the summer of 1895, a young student from the University of Saint Petersburg, Antanas Smetona, stayed in Chodkauskas' house, teaching his elder son Romanas Lithuanian. Besides Sofija, the family included her sister Jadvyga, their elder brother Romanas and younger Tadas.

Sofija had a talent for learning languages – she picked up German from her German governess that she later improved even more while living in a German boarding school in Mitau, where she graduated from a gymnasium. Sofia's grandmother on her mother's side was a Curonian German, so even her mother spoke better German than Polish.

Sofija, born on 13 January 1885, was 11 years Smetona's junior – which at the time was considered a rather sharp age difference between spouses – and met him, still a student, in Gavenonys.

Young, pretty, lively and talkative 19-year-old, freshly graduated from Mitau Gymnasium, married 30-year-old bank employee Smetona in 1904 and the two moved to Vilnius. It wasn't long before Sofija joined the local Lithuanian society, exhibiting her fairly good voice in choirs and operettas, playing in amateur theater productions, actively participating in charity work. Speaking fluent German, she assisted as interpreter and mediator during the German occupation in World War One.

The Smetona family soon became the centre of Lithuanian cultural life in Vilnius, their home was frequented by the likes of Antanas' university mate J.Tūbelis, reverend V.Mironas, author Kazys Puida with his wife Ona Pleirytė-Puidienė, L.Gira, Mikas and Kipras Petraukas, painter A.Žmuidzinavičius, sometimes even by M.K.Čiurlionis and Petras Klimas. Sofija was a good expert on all the policies of her husband and participated in their making without the slightest sign of ennui (unlike many politicians' spouses who would and still do invest most of their time into updating their wardrobes).

Sofija Smetonienė was reputed as a steadily pleasant hostess who would always invite new acquaintance for a visit at her home. Priest and author M.Vaitkus wrote after a visit at Smetona's in Kaunas: “I found Mrs Sofija at home. Tall, slim. Elongated and slightly dark face. Eyes vaguely Mogul. Slight swelling and shading under the eyes. In general, features quite distinctive and uncommon. One can see a good race. The lady often holds a lit cigarette in between her right-hand fingers which makes them sallow. The cigarette owner, moreover, often touches it with her lips, savors it more fully, leaving marks on lip corners. She received me very simply, almost amiably. We started conversing about routine facts of life, as if we were old acquaintances. By the way, is Mr Smetona home? Yes, she said. And then the lady showed me where to go.”

Vacationing in Palanga in 1925, Antanas Vireliūnas, a known linguist who was very ill at the time, felt his health deteriorating (liver inflammation), his lips and tongue turning black and face yellow. Prof. Iz.Tamošaitis visited the patient, accompanied by S.Smetonienė. She told Tamošaitis, who seemed out of his depth: Vireliūnas would not last long. Indeed, he passed away on 23 July.

Friends talked his family out of transporting the body to cemetery in Kaunas – it was summertime, long distance. They agreed to bury the departed in Palanga. Coffin had to be bought in Klaipėda and brought to Palanga. But how to transport it, by what means, where to get it? While men were discussing it, S.Smetonienė procured a car. All that remained for A.Smetona, reverend Šniukšta, Iz.Tamošaitis, and Parlamentarian Kvieska to do was to say homage speeches in the funeral, silently thanking S.Smetonienė for solving all the practical problems.

Experienced diplomats from the US and Germany were often delighted by her liveliness, ability to quickly find mutual understanding, find their favor, maintain conversations with foreigners. Harry Carlson, American consul in Kaunas 1924-1926, characterized Sofija in one of his wires thus: “Mrs Smetonienė is a highly educated woman of Polish origin, there are indications that her family belongs to Polish nobility. She is exceptionally charming and can be said to be one of the three most important Lithuanian women at the moment. She takes great interest in her husband's politics, although she shows no open interest in any sort of social work, she has not been observed paying any particular attention to education or charity. She is certainly a delightful conversationalist, although her talks always contain certain sharpness and irony when she discusses people and events. Mrs Smetonienė is an ardent gambler and it is well known that she plays rather large sums.”

And here is what Soviet diplomat Sobolevsky though of S.Smetonienė: “Smetonienė is sensible, always in the loop, shows lively interest in everything, well-informed.”

Sofija Smetonienė was ready to sacrifice any prior engagement for the sake of her dearest friends. She instantly accepted an invitation to a dinner party held by US diplomats in the honor of Frederick Coleman, head of the American mission in the Baltic states, but shortly afterwards remembered that, unfortunately, she and the President had already been invited to the USSR embassy (as Smetonienė herself put it, she was invited by the “Bolscheviken”).

However, came 12 October and Smetonienė arrived to the American dinner party, declaring that she had withdrawn her promises to the soviets because she prefered present company, even though she’d got into trouble with the Foreign Ministry for not accompanying the President to the Soviets' event. She recounted how she’d spent half an hour arguing with Prime Minister Voldemaras. She did not leave the party before 1 AM, when the President's adjutant came to fetch her, as usual.

Smetonienė was exceptionally fond of the company of F.Coleman – who would occasionally come to Kaunas on business – because he'd gladly play cards with her.

On 27 October, American Consul Heingartner became witness of the following scene at the President's palace: the guests who arrived for 5 o'clock tea were greeted by the President, descending down the stairs in seemingly good humor. After Smetonienė arrived, everyone drank coffee and started to play a new game (a game of dice called golf), getting instructions on its finer points from one of the guests. Smetonienė had never seen the game, yet she cracked it instantly – faster than any of the gentlemen in the room – and played it with great zest, inviting everyone for another round the following day. “She is a born gambler,” Consul Heingartner noted in his diary.

Upon Sofija's becoming the First Lady again (1926), diplomats noted, somewhat surprised, that the new status made not the slightest change in her attitudes – she remained just as cheerful, honest, frank and slightly mocking of those she did not like. Smetonienė mostly smoked Russian cigarettes. She complained that since her husband became President, he had been smoking too much. He had much on his mind and was smoking to calm his nerves.

On 9 September 1927, an armed uprising erupted in Tauragė and other towns, mostly instigated by the social democrats, but by the evening it got stamped out, culprits arrested. Quite unpleasant for the Smetona family – and on the eve of their daughter Marytė's wedding...

Even though developments of the uprising aupset the family a great deal, they hardly could cancel all the wedding arrangements.

At 7 PM, 10 September 1927, a smart-dressed crowd of Kaunas society and foreign diplomats congregated in the town's Arch-Cathedral. Marytė Smetonaitė was marrying President's adjutant, captain of the hussars Aloyzas Valušis. The Cathedral was full of people from all sections of society, most of them standing as all seats were taken. Sofija Smetonienė led captain Valušis to the altar, the President with Marytė following behind.

Photographers' flashes and buzzing of movie cameras constantly disturbed the ceremony. Archbishop declared the couple husband and wife and read a letter from the Pope. The newlyweds left through the side door while all the diplomats were shaking hands with the President and his wife. Only one foreign diplomat got invited to the wedding ball – the US vice-consul Ch.Gerrity, a personal friend of the Smetona family. Gerrity later told his consul that 75 people attended the wedding, raising champagne glasses on the arrival of the newlyweds to the Pressident's palace.

Each of the newlyweds received a glass of champagne and the young captain threw the emptied glass to the floor – such was the custom here. High clergy and military officers in full-dress uniforms surrounded the tables. After dinner, the bride danced with every one of the guests. Members of Sofija Smetonienė's bridge group sent the young couple an antique silver plate as a present.

***

Both sisters – Sofija and Jadvyga Chodkauskaitė – were true patriots and would always maintain Lithuanian pride. Sofija Smetonienė was wife of President Antanas Smetona and Jadvyga – spouse to Prime Minister Juozas Tūbelis. Both were famous for their passionate patriotism. Poland's envoy in Kaunas Franciszek Charvat has reported that in his meetings with the Smetonas, the President would talk to him in fluent Polish, while his wife Sofija would not use her native tongue and insist on talking to the Pole in French, a language that she spoke rather poorly.

The Smetonas usually spent their vacations in Palanga – upon arrival, the President's family would be greeted by burgomaster Jonas Šliūpas and other distinctive town citizens, after which the President would go to his summerhouse. The Smetonas spent their holidays swimming, sunbathing, and resting. After 1934 – the year of Smetona's 60th anniversary – the family found a new holiday spot, Užugiris Court near the President's home village.

The Smetona family spent their holidays in Užugiris differently than in Palanga – Smetonienė would take care of the house, the President's sister Julija oversee the fields. Cooking was Sofija's responsibility.

One evening, A.Smetona agreed to visit duke Konstantinas Radvila who was one year Smetona's senior and a widower with three grown-up children.

In his youth, the duke had been renown for his great physical strength, his passion for hunting and a collection of over 70 rifles. His residence, Taujėnai manor, was a splendid building, but upon closer look appeared to be rather neglected. After the land reform (1922), the duke was left with merely 80 ha of his formerly gigantic estate, not quite enough to maintain his wide lifestyle.

As the President's car stopped outside the manor, two uniformed footmen came instantly and the duke, attired in beautiful antique clothes, emerged from an antechamber to greet the guest.

This was a symbolic meeting – after all, Smetona's forefathers once slavishly toiled in the fields of the duke's ancestry. His younger sister Taida Radvilaitė escorted them to a tastefully arranged table. As she spoke no Lithuanian, the party communicated mostly in Polish, even though the duke was fluent in Lithuanian, with a slight regional accent.

Duke Konstantinas was a well-educated man, graduate of Riga Polytechnics with a degree in forestry from a German university. After the meal, Radvila conducted Smetona around the manor, showing rooms furnished with Louis XIV furniture, paintings, vases and sculptures, presents and prizes for excellent shooting. The guests were also shown into a glasshouse filled with tropical plants.

When footmen closed the car door and saluted the out-bound President, the duke remained in his manor and prospectless life, while Smetona returned to his wife in Užugiris Court – this is how the family preferred to call their new property, avoiding the more traditional “Užugiris Manor.”

Next week, what were Smetona's attitudes towards Polish national minority and the Vilnius question and why his adversaries would call him "King of Jews."

Lithuanian Poles and Antanas Smetona, “King of Jews“ (I)

By: Alfonsas Eidintas / 15min.lt

President

Smetona is sworn in 1938.

Alfonsas Eidintas, historian and Lithuania's former ambassador to the USA, Canada, Mexico, Israel, and Norway, has recently published a second book on Lithuania's inter-war president Antanas Smetona. The book is called "Antanas Smetona and His Environment" and the author has kindly agreed to let 15min.lt share some of its chapters. The following is an extract from a chapter on Smetona's views on national minorities in inter-war Lithuania.

As people started to build an independent Lithuania, they likewise set out to lithuanianize her. The process of lithuanianization did not escape its excesses – attacks against foreign citizens. It was not only the Holly See delegate A.Zecchini who voiced great indignation in his reports to Vatican, but also President Antanas Smetona, who never approved of attacks against Jews and Poles.

***

In the beginning of 1923, non-Lithuanian signs and plates in Kaunas and across the entire country would get an occasional tarring. People would find notes of proclamation glued to walls of their houses, signed by “patriots” and fascist groups that came to be called “smearers” (murzintojai).

While the smearers' actions were being hotly debated in the press, Augustinas Voldemaras (Prime Minister at the time) denounced the tarring of signs, stressing that “every Lithuanian passing through these tarred signs must lower his eyes in shame” and that it gave the country great dishonor abroad. Gradually, nationalistic attacks against Jews (they were being accused of distrusting the recently-introduced national currency, litas, and of demanding privileges) and the smearers' adventures lost momentum.

In regimes run by one man, the latter's personal attitude to racial and national minorities becomes a significant factor in state politics.

In regimes run by one man, the latter's personal attitude to racial and national minorities becomes a significant factor in state politics; therefore, Smetona's policies in Lithuania say much about him as a person. Authoritarian regimes (and such was Lithuania under Smetona 1926-1940) usually oppress their national minorities, turning a blind eye on their needs. The more radical among Smetona's opponents have repeatedly called him “King of Jews,” thus voicing their discontent with the President's tolerant position regarding Jews, Lithuania's most important and populous national minority at the time. But what about local Poles? What policies did Smetona's regime adopt regarding national minorities?

On March 24, 1936, Smetona gave probably the most comprehensive account of his views on Vilnius question (Lithuania's old capital was at the time under Polish rule, tensing relations between the two neighboring countries) and Lithuanian-Polish relations in a lecture called “The Lithuanian Nation and Its Purpose.” The importance of Vilnius he described thus: “Lithuania without Vilnius is missing one wing in her flight upwards, to the future. It is a moderate position: In want of a third of her land, she cannot have a full plan of her tasks, she does not have the importance in the eyes of her neighbors that she could have. Getting it back would add weight on international plane and internal life would be more spacious, management work would be done more purposefully.”

Poles, according to Smetona, must, too, grant Lithuanians their right to self-determination, must renounce their imperial nationalism, since the Lithuanian-Pole type that once had historical existence, was no longer possible. In the olden days, Poles would call conscious Lithuanians “litvomans,” unfaithfull to the common Polish-Lithuanian cause, but today, when Lithuania was free, they quit doing so, yet still sought to maintain the obsolete origine lituanus, natione polonus type and grant it the right to determine Lithuania's lot.

The late Marshall Pilsudski loved throwing the term around whenever it suited him, like in Paris in 1927, yet this dual national type became shaky with the rise of the Lithuanian nation. Even families would break up because of it: “Professor Ivanauskas of our university, nobleman, Lithuanian from Lyda in origin, had one brother who thought himself Belorussian and another – Polish. A whole lot of our noblemen – Biržiškai, Mongirdai, Landbergiai, Pečkauskaitė, Pšibiliauskienė, Putvinskiai and many more – come from families whose fathers or grandfathers regarded themselves as Lithuanian Poles.

Finally, late Narutavičius from Telšiai, a nobleman of Polish nurturing, was a member of the Council of Lithuania and signed the declaration of independent Lithuania. And his real brother, Narutavičius, champion of Pilsudski, was elected Poland's President. Polonized Lithuanians, who support Poland, would like to see the common folk that are still nationally unconscious to follow their suit; those recalling their Lithuanian origin stand in support of the resurgent Lithuania.”

That is why Poland allegedly cries about how Lithuanians persecute Poles and, in return, persecute Lithuanians of Vilnius. “Do we not have Polish gymnasiums and other Polish schools, founded on our common laws? We do, so the Poles are not being wronged, but they seek to have more rights than is their due, in order to influence the resurgent Lithuanian people. After all, these schools are meant for the polonized Lithuanians, not some newcomers from Poland. We seek national revival of our people, while Poles think it's their right to use them as ethnographic material. We would be happy if Poles allowed Lithuanians of Vilnius region to remain Lithuanians. This is where our views clash. Today, language is the most important mark ofr a nation, but not the only one.”

Smetona specified his views even further in LTS assembly of November 1939, probably in an attempt to curb his own radical supporters from the younger generation: “To persecute foreigners is not only dishonorable, it is unwise. The flood of nationalistic currents will have to go on the ebb. Life will make nations break free of a narrow shell of nationalism, look for contacts in culture instead of differences and return to a universal human basis of morality.”

In November 1939, Lithuania got Vilnius back, but – contrary to what was being said – Smetona was not excited about it for several reasons. Garrisons of the Red Army were stationed there and, besides, by its population Vilnius was – even though quite Jewish – predominantly Polish, with Polish language dominating the city. Old myths – that the denationalized Lithuanians of Vilnius region were waiting for mother Lithuania to come, whereby they'd burst into speaking publicly in their native tongue – appeared to be mere fables, while Poles with resolutely Polish identity met the coming of Lithuanians – the new invaders, as they saw it – to Vilnius with hostility.

Vilnius was a prism to reflect on spiritual capacities of the Lithuanian nation – it was being claimed that the existence of the Lithuanian state depended on national resistivity, yet the question arose – how far should the nationalism go. V.Alantas (Jakševičius) raised a point that nationality should not be considered as something extreme, one should not feared to become nationalist in the true sense of the word. He was critical of Lithuanians' hospitality and welcoming nature, as it was harmful to Lithuania's interests.

The authorities organized language courses, forcing people to drill Lithuanian and all its rules into their heads, without quite understanding them.

The government undertook vigorous lithuanianization of the city, replaced public signs, published all information in Lithuanian, speaking and writing in Lithuanian became institutional requirement – all of a sudden, the city turned foreign to majority of its townspeople.

The authorities organized language courses, forcing people to drill Lithuanian and all its rules into their heads, without quite understanding them. The present author, newcomer from Žemaitija (Western Lithuania), used to rent a room in Žvėrynas, Vytautas street, with a landlord of Belorussian descent, R.I.P Valentinas Syvijus, who, having experienced the intensity of the pre-war language courses, would wake up from sleep or after ten pints of beer (his absolute limit) and, as late as 1974, would reel off in Lithuanian with a heavy Slavonic accent: “Daiktavardiiis yra kalbos daliis, kurį galima pamacyci yr apačioci.” (Noun is part of speech that you can see and touch.”) He still spoke the language poorly, even though his entire family – who came from Molėtai, on the Lithuanian side of the demarcation line – used only Lithuanian.

Historian Š.Liekis came up with an example to show how much the Lithuanian military, who entered Vilnius, were taken aback by the real, not nominal, linguistic situation in the city.

Lieutenant Mikalauskas of the Lithuanian army and his subordinates spent two weeks going from one village to another with an assignment to help “real sons and daughters of Lithuania,” that is, Lithuanians of Vilnius region. Lieutenant and his soldiers were in for a great shock. They were more than surprised when they did not come across a single Lithuanian-speaker in the villages they marched through – they even got a feeling of slight discomfort, as if they were in a foreign country. Some hope lit their faces only around Šalčininkėliai, Mielagėnai, Kirdeikiai and Laužonys, where they found entire Lithuanian-speaking villages.

There were some radical suggestions, too. The House of Commerce stated, in its 1939 “Economic Bulletin” (for official use only, not for publishing), that Lithuania would now have several hundred thousand pro-Polish citizens and moving several ministries to Vilnius would amount to nothing more than a “war against titans,” that one faced a great mass of Poles that could not be just dissolved. Suggestions were raised to tear this nest apart – physically and economically, with “siedlungspolitik” west to east, etc. Polish burghers were to be moved westwards, leaving all the treasures of Vilnius to Lithuanians; the more Lithuanian the region, the more integral the capital.

Skaitykite

daugiau: http://www.15min.lt/en/article/culture-society/lithuanian-poles-and-antanas-smetona-king-of-jews-i-528-200703#ixzz1sf3Q0Y68

Antanas Smetona, “King of Jews“ (II)

By: Alfonsas Eidintas / 15min.lt

Renatos

Mikalajūnaitės/Istorinė Prezidentūra nuotr. /

Mylimiausiu prezidentu išrinktas Antanas Smetona

Alfonsas Eidintas, historian and Lithuania's former ambassador to the USA, Canada, Mexico, Israel, and Norway, has recently published a second book on Lithuania's inter-war president Antanas Smetona. The book is called "Antanas Smetona and His Environment" and the author has kindly agreed to let 15min.lt share some of its chapters. The following is an extract from a chapter on Smetona's views on the Jewish national minority in inter-war Lithuania.

As people started to build independent Lithuania, they likewise set out to lithuanianize her. The process of lithuanianization did not avoid its excesses – attacks against foreign citizens. It was not only the Holly See delegate A.Zecchini who voiced great indignation in his reports to Vatican, but also President Antanas Smetona who never approved of attacks against Jews and Poles.

Read beginning of the chapter Lithuanian Poles and Antanas Smetona, "King of Jews" (I)

The same [House of Commerce 1939] bulletin urged to define a policy for Jews in Vilnius region, saying that it was unacceptable to leave the most profitable industry – commerce – in Jewish hands, that they needed to be resettled [from the newly-regained Vilnius] and not to other towns, but to rural settlements, to work in agriculture; Lithuanians, it said, had to stop valuing only land: “If we want to live, let's divide up the towns and shove Jews into the country where they in specia are bound for extinction, because they will not manage to do hard and decent work. The gain will be two-fold: Jews will be pushed into passive and prospectless rural existence and put on the verge of extinction.”

This was a very open and Nazi-like incitement – Smetona's government policies never included such drastic measures.

Having regained our state, we want and we must be just in dealing with our minorities. Since we do not demand them to melt, to drown within our nation, we grant them the right to a native tongue, allow them to associate with their own kind in matters of culture.

Smetona had cooperated with Jewish colleagues under the Tzar, during election to the Russian Duma; Jews participated in the Council of Lithuania. So when the 1922 Constitution was being discussed, Smetona supported provisions granting cultural autonomy for national minorities, yet opposed privileges, creating “states within a state.” He protected the status of Lithuanian as a state language, often speaking out against derogations and persecution of minorities, urging to respect their culture: “Having regained our state, we want and we must be just in dealing with our minorities. Since we do not demand them to melt, to drown within our nation, we grant them the right to a native tongue, allow them to associate with their own kind in matters of culture. In exchange, they must be our land’s – therefore, territorial – patriots, love Lithuania and respect the Lithuanian people. They must be loyal to Lithuania, stick to the laws not out of coercion, but out of conscience. Therefore, our national minorities are not aliens, but fellow citizens, not foreign-ethnic, but different-ethnic.”

Smetona, himself a member of a small nation, was sensitive to problems of the small ones (back in1913, he wrote in a publication called “Hope” that nationalism had two sides to it: “Nationalism of the stronger nation turns into chauvinism, that of the weaker – patriotism.”).

“A small nation, of course, is not equal to a big one, one race is not equal to another, but does it follow from this inequality that a nation must slave for another or disappear altogether? The Egyptians are not Aryans, but no one can deny the greatness of their culture. Japanese are a yellow race, but their might today is indisputable, their culture is deep and special. Jews are Semites, a tiny nation that used to live around Palestine, and what giant impact have they made on mankind. They gave us the Holly Scriptures that touched all nations of the world. Which corner of this earth lacks a Bible? None. A tiny nation of Norwegians – and they have given so many brilliant people, authors, and musicians. (...) In proportion, small nations can easily match big ones creatively, in the arts, sciences, technology. Diversity and not unification is the mover of cultural progress,” Smetona said in a congress in 1935.

Neither Smetona, nor his party, Lithuanian Nationalist Union (LTS), promoted racism or antisemitism, even though some groups would hold occasional nationalistic actions or smear Jewish shop windows and doors. Among the most aggressive attackers against Jewish traders were their Lithuanian competitors, businessmen, and their publication “Verslas” (“Business”). Meanwhile, Smetona and LTS leadership always maintained close ties with Jewish financiers and trading groups.

In Jewish press and literature, Smetona was depicted as an incredibly tolerant Lithuanian politician – an image that prompted bitter Lithuanian radicals to dub him the “King of Jews.”

If there is any basis for the claim that the Lithuanian tradition does not recognize antisemitism, then it should not surprise us that Mr Smetona, who has both his feet in the historic soil of his nation, is untouched by either antisemitism or chauvinism.

In 1932, Izidorius Kisinas authored a book for Jewish pupils called “Antanas Smetona, President of the Republic of Lithuania,” published in Hebrew in Vilkaviškis. According to Kisinas, “if there is any basis for the claim that the Lithuanian tradition does not recognize antisemitism, antisemitism as a dominant social current, then it should not surprise us that Mr Smetona, who has both his feet in the historic soil of his nation, is untouched by either antisemitism or chauvinism (if, regretfully, such phenomena have been observed lately, then the influence of Mr Smetona and the better part of the Lithuanian society is our guarantee that trends within certain groups will not stray us away from the historic path (...) and good Lithuanian-Jewish relations).”

However, Smetona's attitudes were completely different regarding the Jewish left and those Jews who participated in Lithuania's revolutionary movement, active members of the Communist Party and communist underground. Perhaps it was the Jews – who preferred speaking other languages (not Lithuanian) – that Smetona intended this remark, uttered in the LTS convention on 5 January 1935: “I could reprove one minority group for having within their ranks those who have not shown due respect for the national Lithuanian language. Not having mastered it properly, they like using one of our neighbours’ languages in public. This habit turns majority of the population against it.”

Smetona expressed an uncomplicated understanding of the relation between the Lithuanian nation and the others: “Lithuanians are builders of their state, while national minorities are their aides, they must love Lithuania and respect the Lithuanian nation, be loyal to Lithuania.” His magnanimity, however, was not extended to all Jews. As B.Ivanov notes, the nationalist press mostly reflected the strategy of integration for national minorities, i.e., questions of their loyalty, since nationalists paid much attention to Jews and tried nurturing a highly differentiated image for them, distinguishing among various groups on the basis of national and public loyalty.

Nationalists would put loyal Jews into two main categories: Zionists and religious Orthodox Jews that presented no serious challenge in terms of public loyalty. It was based on certain Jewish sense of honour, interpreted as national self-consciousness, reliability, fairness, usefulness to Lithuanian nationalism and nationalists. The kind of Jew who would not shun spilling blood in Palestine, whom the Lithuanian environment nurtured into a modern man in terms of national feeling. Lithuanians themselves, it was claimed, could learn national consciousness from him.

The nationalists' attitudes towards Jewish politics were rather inconsistent – they approved of the Jewish role and support in dealing with Klaipėda and Vilnius questions. Meanwhile their wish to participate in municipal and later parliamentary elections was deemed an “unjustified” ambition to further expand their influence.

Skaitykite

daugiau: http://www.15min.lt/en/article/culture-society/antanas-smetona-king-of-jews-ii-528-204355#ixzz1sf4CpkGo

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

No flowers for Smetona

- Posted by - (0) Comment

Ohio crypt holds remains of first Lithuanian President,

yet he has been forgotten here in a Mausoleum tucked

away in a Catholic Cemetery east of Cleveland, USA.

By Frank Passic

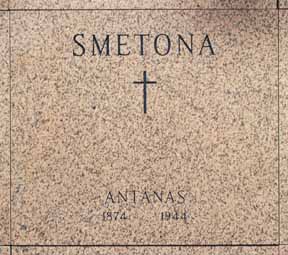

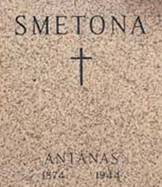

There are no flowers at his crypt, although the Mausoleum is filled with them on the vaults of others nearby. He was the President, yet you would not know that by reading the simple inscription found upon his nameplate. His image was on a coin, a banknote, various stamps and medals. Yet he has been forgotten here in a Mausoleum tucked away in a Catholic Cemetery east of Cleveland, Ohio, USA.

His body has already been moved once since his death. But his remains haven’t been taken back to Lithuania since Lithuanian independence was restored, unlike the remains of his counterpart, President Kazys Grinius’ were. So his remains lay here in Ohio, far away from the country he loved and served.

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

No flowers for Smetona

- Posted by - (13) Comment

Ohio

crypt holds remains of first Lithuanian President,

yet

he has been forgotten here in a Mausoleum tucked

away

in a Catholic Cemetery east of Cleveland, USA.

By Frank Passic

There are no flowers at his crypt, although the Mausoleum is filled with them on the vaults of others nearby. He was the President, yet you would not know that by reading the simple inscription found upon his nameplate. His image was on a coin, a banknote, various stamps and medals. Yet he has been forgotten here in a Mausoleum tucked away in a Catholic Cemetery east of Cleveland, Ohio, USA.

His body has already been moved once since his death. But his remains haven’t been taken back to Lithuania since Lithuanian independence was restored, unlike the remains of his counterpart, President Kazys Grinius’ were. So his remains lay here in Ohio, far away from the country he loved and served.

He was Antanas Smetona (1874-1944), the first and fourth President of the Republic of Lithuania. A writer and journalist by profession, Smetona was active in the Lithuanian National Movement. He was a member of the Lithuanian National Council and one of the signers of the Lithuanian Declaration of Restoration of Independence in 1918. He was a member of the Nationalist Party, and his regime was in power until the 1940 Soviet invasion. Smetona was able to successfully flee Lithuania when the USSR invaded the country on June 15, 1940, being the only President to do so from among the three Baltic Republics.

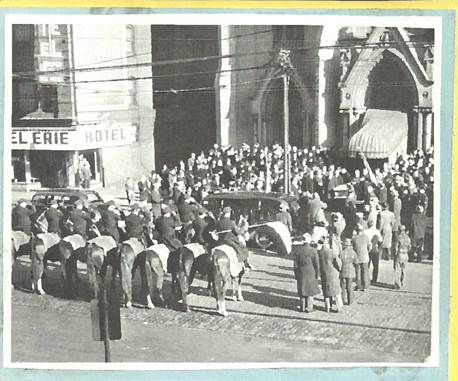

Smetona eventually was allowed to settle in the United States as a private citizen, and delivered speeches on national radio and to communities to promote Lithuanian independence. His untimely death from smoke inhalation occurred as a result of an overheated furnace at his Cleveland home on January 9, 1944. Dignitaries filled St. John’s Cathedral in Cleveland for the funeral on January 13. Eight Cleveland mounted police, led by an office, formed an honorary guard which escorted the corpse to the church and stood sentinel with the Lithuanian flag lowered during the services. Bishop Edward F. Hoban led the solemn pontifical requiem mass, with Chicago’s Rev. A. M. Linkus preaching the funeral. Smetona’s remains were then interred in the Knollwood Mausoleum until 1975.

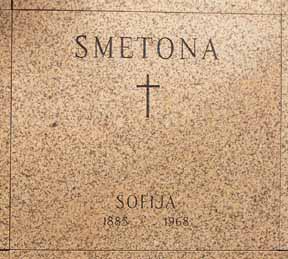

President Antanas Smetona is now interred in the Crucifixion Mausoleum in All Souls Cemetery, located at 10366 (office at 103400) Chardon Road, Chardon Township in Geauga County, Ohio, zip code 44024. The Mausoleum is located in Section 23, and Smetona’s crypt is No. 103. His wife Sofija (1885-1968) is interred next to him on the right. For the official record, the GPS location of this Mausoleum is North 41 degrees, 35 minutes, 600 seconds by West 081 degrees, 16 minutes, 208 seconds.

In 2006 Lithuanian Numismatic Association member Lou Merkys paid a visit to Smetona’s resting place and took several photographs at the site which we are sharing here with our readers. The Mausoleum is filled with many flowers that have been placed on the faceplates of vaults of the deceased, but no flowers have been placed on those of the Smetonas.

Numismatists are quite familiar with Smetona’s image on the obverse of the 1938 10 litas coin (KM-84) commemorating the 20th anniversary of independence. The obverse features Smetona’s image, facing left. The legend translates, “State President A. Smetona, 10 Litas.” The reverse depicts the Columns of Gediminas emblem in the center, with the text translating, “Lithuania 1918-1938, Twenty Years of Independence.” The inscription on the edge translates, “In Unity Lies the Strength of the Nation.” This coin was struck in 75% silver, and measures 32 mm. in diameter.

This was the last coin issued by the Republic of Lithuania before the Soviet invasion. Designed by sculptor Juozas Zikaras, it is also one of the most popular and scarcest of the pre-War series of 14 coins. Only 170,000 were minted at the Mint of Lithuania in Kaunas. When the coins were released into circulation, they immediately had a collector’s value of 12 litas’.

1 The Lithuanian Mint also struck an example of the coin in gold in the summer of 1938 and presented it to the Lithuanian President.

2 This coin had a limited circulation period. When the Soviet’s invaded Lithuania two years later, anything with the image of President Smetona became a special target, and was outlawed. One graphic account by J. Yuknis, Jr. states:

3 When the Russian army occupied Lithuania on June 15, 1940, Moscow ordered destroyed every item with a portrait of President Smetona. On June 19, people were ordered to turn those coins in within one week’s time to the bank, or post office, or police. Rumors were circulating that if such a coin would be found in possession of anybody, there might be a death penalty. Frightened people stood in line at designated places to deliver those ‘capitalistic’ coins. Naïve Russians wanted to erase the name of that great President of Lithuania from pages of history. But they failed…Russians murdered all the philatelists in Lithuania, when their NKVD found some Smetona stamps in their stamp albums. That is a fact!”

Plans were also made in 1938 to strike a new 2 litas coin, bearing the image of Smetona. Dies were prepared and the Brussels Mint in Belgium, and patterns were struck there, both in silver and bronze. These measured 23 mm. in diameter. The master dies were then shipped to the Mint of Lithuania in Kaunas. The bust of Smetona on the 1938 2 litas patterns feature the President wearing a suit coat, while the image on the 10 litas coin did not. One version had the 20th anniversary year theme on the reverse with a Columns of Gedminas emblem, while another version used the traditional Vytis emblem. In any event, this coin was not approved in time for it to be struck, due to the rapidly deteriorating political situation in Europe.

Although there are no flowers at Smetona’s interment site in Ohio, the website www.findagrave.com allows people to leave “virtual flowers” and notes on his burial memorial there. I will be writing specifically about this website in a future article. For now however, on the main page on the left, click on “Famous Grave Search.” Type in “Antanas Smetona” in space provided and click “Search.” You’ll then see his name on the left. Click on his name and you’ll get his listing. You can leave your flowers and notes for Smetona there.

FOOTNOTES

1. Karys, Jonas K. Nepriklausomos Lietuvos Pinigai,

Aukselis, New York, 1953, pg. 205.

2. Ibid., pg. 206.

3. Yuknis, J. Jr. “Lithuanian-Americana: The Last

President of Lithuania,” American-Lithuanian Philatelic Specialist. June 1948,

pg. 20.

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

The book, “1939, The Year that Changed Everything in Lithuania’s History” reveals the unflattering response by the top leadership, their abdication, and flight from the nation, leaving the population defenseless… without any responsible and effective resistance… as if independence never happened

- Posted by - (0) Comment

Go to our Section 5 to participate in the discussion

Book author: Sarunas Liekis

In a commentary to our VilNews article series "Lithuania and the Soviet Union 1939-1940" (Section 10 - HISTORICAL LITHUANIA) Tony Mazeika from Mission Viejo in California writes the following:

"It is necessary to read the full account of Lithuania's leadership response to Soviet demands and occupation in 1940. The book, "1939, The Year that Changed Everything in Lithuania's History", Arnas Liekis, reveals the unflattering response by the top leadership, their abdication, and flight from the nation, leaving the population defenseless...without any responsible and effective resistance. It's as if independence never happened. Lithuania, together with Latvia & Estonia, make no formal military resistance knowing that Finland fought in 1939-1940 and survived a Soviet onslaught. Much more need to be disclosed about those "patriots" who chose to run rather than fight for their nation."

Tony Mazeika

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - (0) Comment

Our VilNews Associate Editor, Vin Karnila, has edited the four articles we have presented on the topic "Lithuania and the Soviet Union 1939-1940" from the personal memoirs of Juozas Urbšys. Here is his response to Mr. Mazeika's commentary:

Easy to say that they should have organized formal Military resistance – and get slaughtered

Vin Karnila

I would like to thank you Mr. Mazeika for sharing your thoughts with us and making us aware of what I'm sure is a very interesting book written by Arnas Liekis.

You bring up a topic that has been discussed many times throughout the years following 1940. The members of the Lithuanian delegation that were involved in the negotiations with Russia have always claimed that they knew that Russia at any time they chose could have invaded Lithuania. They also felt that if Russia did in fact invade, whether there was organized military resistance or not, this would result in catastrophic consequences for Lithuania and its people. Throughout the negotiations they said that what they were trying to achieve was the best possible outcome for Lithuania. In the end what they achieved was the best possible outcome that Russia would allow.

The topic of the courageous people of Finland and their organized military resistance to Russia's invasion of their homeland in relation to the fact that Russia's invasion of Lithuania in 1940 occurred without a shot being fired has also been discussed many times. The question remains how much did Lithuania know or did not know about Finland's armed resistance to Russia in what is known as the "Winter War"?

3 October 1939 the Lithuanian delegation flew to Moscow to begin the negotiations with Russia. 30 November 1939 Russia attacked Finland to begin the "Winter War". By March of 1940 both sides began to negotiate a peace treaty. Did Lithuania know that in spite of the great courage of the Finns the primary factor in Finland's success was that the Winter War was fought in some of the harshest of winter weather conditions and in equally harsh terrain? This harsh terrain the Finns knew like the back of their hand and the weather conditions to them was normal winter weather? Did Lithuania know that if Russia attacked across the gentle rolling hills and flat farmlands of Lithuania in spring or summer that the advantage of weather and terrain, that so greatly helped the Finns, would only make Russia's evil task easier? An invasion of Lithuania by Russia in the spring or summer of 1940 would have been a military situation completely the opposite of the Finland's and Russia's Winter War. Did Lithuania know that whatever peace agreement Finland and Russia came to that it would end up being short lived? Had Lithuania taken notice of the fact that no Western power had come to Finland's aid with any meaningful support? From all reports, Lithuania realized that their Military, no matter how courageously they fought, was no match against the might of Soviet Russia's army.

Many comments have been made and questions asked about the large number of government and Military top officials that left after 15 June 1940. Why didn't they stay? Why didn't they stay and resist? How could they leave their homeland? I would say that the real answers to these questions can only be answered by these top officials that left. Some left almost immediately as if they knew what would happen once Russia occupied the country. Others left after they saw what Russia was doing now that they occupied the country. In fact many people that had the means to do so left once they understood what their future would be at the hands of Russia.

All these questions to all these situations I have asked myself over and over. Again and again I come to the conclusion that more than seventy years after these events occurred, while I'm sitting in the comfort of my home and while I can walk the streets of Vilnius without (for the time being) having to worry about being run over by a Russian tank, shot by a Russian soldier, kidnapped by the NKVD, put in a gulag or executed, I am really not in a position to judge people who were trying to do the best they could for our country and simply trying to survive during very difficult and dangerous times. I guess it could be kind of easy for some to say that they should have organized formal Military resistance – and got slaughtered. It could also be easy for some to say that the top officials and the people of means should have stayed – and got executed, imprisoned, put in gulags or sent to Siberia. Personally I can't judge these people for their actions because I wasn't alive then and I wasn't involved in these dangerous and difficult times. I also refuse to be a "Monday morning quarterback" and go on and on talking about all of the "should haves" for the same reasons I just stated. The opinions of others about these matters though are something I am very interested in.

Having said all this I must say that the discussion of what happened, what did not happen, why it did happen and why it didn't happen during these times are matters that will continue to occupy my thoughts – I'm still trying to understand and make sense of all of it. Again I would like to thank you Mr. Mazeika for sharing your thoughts with all of us and I would also like to thank you for letting us know about the book by Arnas Liekis - 1939, The Year that Changed Everything in Lithuania's History. I'm sure that I am not the only one out there looking for more information about this period of Lithuania's history and I'm sure that I'm not the only one looking for more information about this so that I can try to make more sense of everything.

Dear readers, I'm sure that Mr. Mazeika and I are not the only ones out there that are interested in what happened during these times and we are not the only ones with opinions. We would please invite you to share information and your opinions on this topic with all our readers throughout the world. I'm sure this is something we all are trying to understand better.

Su pagarbe

Vin Karnila

Associate editor

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - (1) Comment

The book, "1939, The Year that Changed Everything in Lithuania's History” reveals the unflattering response by the top leadership, their abdication, and flight from the nation, leaving the population defenseless... without any responsible and effective resistance… as if independence never happened

Book author: Sarunas Liekis |

Tony Mazeika |

In a comment to our VilNews article series "Lithuania and the Soviet Union 1939-1940" ( Section 10 - HISTORICAL LITHUANIA) Tony Mazeika from Mission Viejo in California writes the following:

"It is necessary to read the full account of Lithuania's leadership response to Soviet demands and occupation in 1940. The book, "1939, The Year that Changed Everything in Lithuania's History", Arnas Liekis, reveals the unflattering response by the top leadership, their abdication, and flight from the nation, leaving the population defenseless...without any responsible and effective resistance. It's as if independence never happened. Lithuania, together with Latvia & Estonia, make no formal military resistance knowing that Finland fought in 1939-1940 and survived a Soviet onslaught. Much more need to be disclosed about those "patriots" who chose to run rather than fight for their nation."

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Our VilNews Associate Editor, Vin Karnila, has edited the four articles we have presented on the topic "Lithuania and the Soviet Union 1939-1940" from the personal memoirs of Juozas Urbšys. Here is his response to Mr. Mazeika's commentary:

Easy to say that they should have organized formal Military resistance – and get slaughtered

Vin Karnila

I would like to thank you Mr. Mazeika for sharing your thoughts with us and making us aware of what I'm sure is a very interesting book written by Arnas Liekis.

You bring up a topic that has been discussed many times throughout the years following 1940. The members of the Lithuanian delegation that were involved in the negotiations with Russia have always claimed that they knew that Russia at any time they chose could have invaded Lithuania. They also felt that if Russia did in fact invade, whether there was organized military resistance or not, this would result in catastrophic consequences for Lithuania and its people. Throughout the negotiations they said that what they were trying to achieve was the best possible outcome for Lithuania. In the end what they achieved was the best possible outcome that Russia would allow.

The topic of the courageous people of Finland and their organized military resistance to Russia's invasion of their homeland in relation to the fact that Russia's invasion of Lithuania in 1940 occurred without a shot being fired has also been discussed many times. The question remains how much did Lithuania know or did not know about Finland's armed resistance to Russia in what is known as the "Winter War"?

3 October 1939 the Lithuanian delegation flew to Moscow to begin the negotiations with Russia. 30 November 1939 Russia attacked Finland to begin the "Winter War". By March of 1940 both sides began to negotiate a peace treaty. Did Lithuania know that in spite of the great courage of the Finns the primary factor in Finland's success was that the Winter War was fought in some of the harshest of winter weather conditions and in equally harsh terrain? This harsh terrain the Finns knew like the back of their hand and the weather conditions to them was normal winter weather? Did Lithuania know that if Russia attacked across the gentle rolling hills and flat farmlands of Lithuania in spring or summer that the advantage of weather and terrain, that so greatly helped the Finns, would only make Russia's evil task easier? An invasion of Lithuania by Russia in the spring or summer of 1940 would have been a military situation completely the opposite of the Finland's and Russia's Winter War. Did Lithuania know that whatever peace agreement Finland and Russia came to that it would end up being short lived? Had Lithuania taken notice of the fact that no Western power had come to Finland's aid with any meaningful support? From all reports, Lithuania realized that their Military, no matter how courageously they fought, was no match against the might of Soviet Russia's army.

Many comments have been made and questions asked about the large number of government and Military top officials that left after 15 June 1940. Why didn't they stay? Why didn't they stay and resist? How could they leave their homeland? I would say that the real answers to these questions can only be answered by these top officials that left. Some left almost immediately as if they knew what would happen once Russia occupied the country. Others left after they saw what Russia was doing now that they occupied the country. In fact many people that had the means to do so left once they understood what their future would be at the hands of Russia.

All these questions to all these situations I have asked myself over and over. Again and again I come to the conclusion that more than seventy years after these events occurred, while I'm sitting in the comfort of my home and while I can walk the streets of Vilnius without (for the time being) having to worry about being run over by a Russian tank, shot by a Russian soldier, kidnapped by the NKVD, put in a gulag or executed, I am really not in a position to judge people who were trying to do the best they could for our country and simply trying to survive during very difficult and dangerous times. I guess it could be kind of easy for some to say that they should have organized formal Military resistance – and got slaughtered. It could also be easy for some to say that the top officials and the people of means should have stayed – and got executed, imprisoned, put in gulags or sent to Siberia. Personally I can't judge these people for their actions because I wasn't alive then and I wasn't involved in these dangerous and difficult times. I also refuse to be a "Monday morning quarterback" and go on and on talking about all of the "should haves" for the same reasons I just stated. The opinions of others about these matters though are something I am very interested in.

Having said all this I must say that the discussion of what happened, what did not happen, why it did happen and why it didn't happen during these times are matters that will continue to occupy my thoughts – I'm still trying to understand and make sense of all of it. Again I would like to thank you Mr. Mazeika for sharing your thoughts with all of us and I would also like to thank you for letting us know about the book by Arnas Liekis - 1939, The Year that Changed Everything in Lithuania's History. I'm sure that I am not the only one out there looking for more information about this period of Lithuania's history and I'm sure that I'm not the only one looking for more information about this so that I can try to make more sense of everything.

Dear readers, I'm sure that Mr. Mazeika and I are not the only ones out there that are interested in what happened during these times and we are not the only ones with opinions. We would please invite you to share information and your opinions on this topic with all our readers throughout the world. I'm sure this is something we all are trying to understand better.

Su pagarbe

Vin Karnila

Associate editor

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

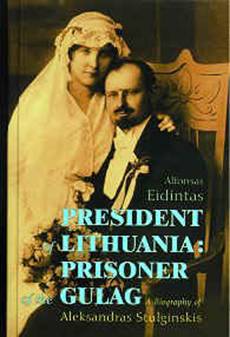

Aleksander Stulgisnkis, Lithuania’s President between 1921 and 1926, decided to stay in his homeland even when the Soviet’s attacked in 1940... He paid a high price...

Cover of the book by Dr. Alfonsas Eidintas, “President of Lithuania:

Prisoner of the gulag (A biography of Alexander Stulginskis).”