THE VOICE OF INTERNATIONAL LITHUANIA

|

VilNews has its own Google archive! Type a word in the above search box to find any article.

You can also follow us on Facebook. We have two different pages. Click to open and join.

|

Archive for April, 2012

- Posted by - (0) Comment

Rūta Šepetys and Ellen Cassedy

Probably our relatives brushed shoulders in the marketplace

Rūta Šepetys and Ellen Cassedy interviewed by Jennifer Virškus

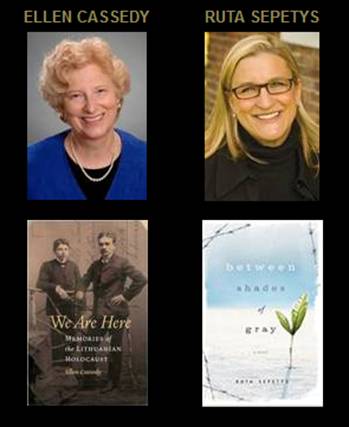

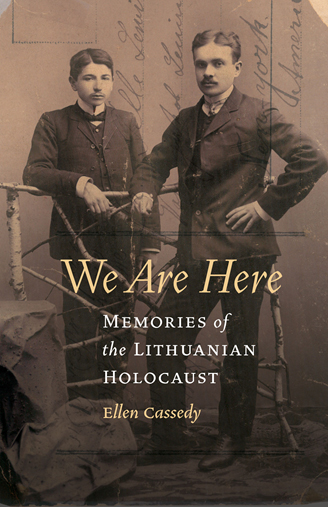

Two new books making a splash in the literary world—Between Shades of Grey by Rūta Šepetys and We Are Here: Memories of the Lithuanian Holocaust by Ellen Cassedy—take place in WWII Lithuania. Though the two women's stories begin in much the same place—Sepetys's grandfather is from a village near Biržai, while Cassedy's great-grandfather hails from Rokiškis only 60km away—the books, and their stories, couldn't be more different. We Are Here is a first person memoir about Cassedy's journey to discover her Litvak heritage while studying Yiddish at Vilnius University. Between Shades of Grey is a young adult fiction novel about a 15-year-old girl who is deported to Siberia along with her mother and younger brother.

Individually, the books have met with incredible success. Between Shades of Grey, which came out in paperback this month in the US, has been translated into twenty-five languages and sold in thirty countries. Only in bookstores for a little over a month, We Are Here is racking up rave reviews at home and abroad. When speaking of the book, which will be released in Lithuania in May, former president Valdas Adamkus said, “This eloquent book can help us to reach out, open our hearts, and rediscover one another in a spirit of mutual understanding.”

Indeed, the need for understanding is a theme in both books, and together, they provide a more complete portrait of a time in history when Lithuania's identity was at its most complex—not only for their readers, but for the authors, too. “I went to Lithuania, hoping to decide who was right and who was wrong; to put people in a column, who was a victim, who was a killer. And then those lines began to blur,” says Cassedy.

Šepetys went one step further, “The intersection that I've experienced [between the ethnic Lithuanian fear of the Soviets and the Litvak fear of the Nazis] is one of regret … People that I've spoken to say that some of their greatest regrets weren't the things that they forgot to pack with them; they were human interactions with people. Something that was said or done, a suspicion or paranoia; but they also explained that those are the casualties of war.”

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - (2) Comment

Rūta Šepetys and Ellen Cassedy

Probably our relatives brushed shoulders in the marketplace

Rūta Šepetys and Ellen Cassedy interviewed by Jennifer Virškus

Two new books making a splash in the literary world—Between Shades of Grey by Rūta Šepetys and We Are Here: Memories of the Lithuanian Holocaust by Ellen Cassedy—take place in WWII Lithuania. Though the two women's stories begin in much the same place—Sepetys's grandfather is from a village near Biržai, while Cassedy's great-grandfather hails from Rokiškis only 60km away—the books, and their stories, couldn't be more different. We Are Here is a first person memoir about Cassedy's journey to discover her Litvak heritage while studying Yiddish at Vilnius University. Between Shades of Grey is a young adult fiction novel about a 15-year-old girl who is deported to Siberia along with her mother and younger brother.

Individually, the books have met with incredible success. Between Shades of Grey, which came out in paperback this month in the US, has been translated into twenty-five languages and sold in thirty countries. Only in bookstores for a little over a month, We Are Here is racking up rave reviews at home and abroad. When speaking of the book, which will be released in Lithuania in May, former president Valdas Adamkus said, “This eloquent book can help us to reach out, open our hearts, and rediscover one another in a spirit of mutual understanding.”

Indeed, the need for understanding is a theme in both books, and together, they provide a more complete portrait of a time in history when Lithuania's identity was at its most complex—not only for their readers, but for the authors, too. “I went to Lithuania, hoping to decide who was right and who was wrong; to put people in a column, who was a victim, who was a killer. And then those lines began to blur,” says Cassedy.

Šepetys went one step further, “The intersection that I've experienced [between the ethnic Lithuanian fear of the Soviets and the Litvak fear of the Nazis] is one of regret … People that I've spoken to say that some of their greatest regrets weren't the things that they forgot to pack with them; they were human interactions with people. Something that was said or done, a suspicion or paranoia; but they also explained that those are the casualties of war.”

- Ellen Cassedy

“The intersection that I've experienced [between the ethnic Lithuanian fear of the Soviets and the Litvak fear of the Nazis] is one of regret … People that I've spoken to say that some of their greatest regrets weren't the things that they forgot to pack with them; they were human interactions with people. Something that was said or done, a suspicion or paranoia; but they also explained that those are the casualties of war.”

- Rūta Šepetys

Neither of the women's upbringing had been particularly “Lithuanian”—or, in Cassedy's case, particularly Jewish. They were raised in mixed-heritage American homes, sprinkled with ethnic flavor. Cassedy's mother used Yiddish words in her daily speech, “We'd be in the kitchen and she would say, 'Hand me that shissel,' meaning that bowl;” but her name comes from her Irish-protestant father. Šepetys spent her childhood explaining her name to the people around her, “Everyone sees Rūta Šepetys and they're asking, and I'm constantly responding, I'm Lithuanian.” But while her grandfather was very connected to the Lithuanian community and they had all the traditional foods and holidays, she herself had no exposure to it outside her home.

Though they did not know each other, both women took their first trip to Lithuania around the same time—in the early 2000's. Šepetys was on a trip with her brother to find out more about her father's youth, “I was meeting cousins … [My father] was in a DP camp for 9 years, so there are no photographs. I asked if they had any photos … and they told me that they had burned them all because they couldn't let anyone know that they were related.” Her grandfather was an officer in the Lithuanian army; when he fled, the rest of his family was put on the Soviet deportation list, just by association. “[My cousins] told me that some of my grandfather's extended family had been deported—I had no idea that the deportations had affected our family. And then to find out that … the freedom that I have as an American perhaps came at the expense of someone else.” She says that the character of Joana in her book represents her father's journey of fleeing Lithuania, going into the DP camp. “I think how much I take for granted on a daily basis, and when I learned that, I thought, 'Oh my gosh!' I was so ignorant. I was almost ashamed that I had no idea that this part of history had affected my family.” That was when she decided she had to tell the story.

A loyalty to Lithuania itself wasn't a part of Cassedy's upbringing. “Where exactly is Lithuania? That wasn't really how I thought about it. I thought of Eastern Europe as a whole, and where was the exact spot, I didn't know.” Her mother had passed away, and she had begun to feel she had lost contact with that part of her heritage. She wanted to study Yiddish in the region where her grandfather was from and decided to enroll at the Vilnius Yiddish Institute—though she did not have the overwhelming support of her peers. “People would say to me, 'There's no point going there, there's nothing there.' That's a very common attitude for Jews in my generation to say.” But she didn't believe that.

“I began this journey in a rather one-dimensional way. I wanted to go to Lithuania and connect to my past, only my past, I wasn't seeing outside of the Jewish past. And then I got knocked over by these two surprises.” Just before Cassedy left for Lithuania the first time, her uncle revealed a secret to her about his activities during the Holocaust while living in the ghetto in Šiauliai. When she got to Rokiškis, she was told that there was an elderly man who wanted to speak to her about the things he had witnessed during the war. “Those two things really threw everything up in the air for me and launched me on this really life-changing journey, that really changed how I thought about Lithuania, how I thought about my family, thought about all people; so it really pushed me into a very different place.”

For both women, the experience of writing their books connected them to Lithuania in a way they had not imagined before. “As I started writing this book and getting involved in this project of looking at how Lithuania has been engaging with its 20th century past and with the Holocaust … I went there and started meeting people … and that has made me feel more connected and made me feel like, 'Well yes, I am Lithuanian,'” explained Cassedy.

“My family history—definitely surprising—was that my father was not familiar with what had happened to his family until 1991 when he went back.” She says even then they didn't share the full details with him; their freedom was still fragile. “You didn't talk about what happened in Siberia.”

Both Cassedy and Šepetys express a desire to start a conversation about the events of WWII. “I think that what Ellen is doing is so important, because it's a wound, a wound on Lithuania. And it will continue to bleed until we can clot it somehow,” says Šepetys. “We're third parties, Ellen and I. We didn't loose family members (Editors note: Ellen actually did.), and I understand there's a lot of deep-seeded anger and resentment, but I hope that we can create a dialogue.” Though, she stresses that the crimes of Stalin and Hitler cannot be lumped together.

What became clear to Cassedy was a sense of competing martyrdom; every group wanted to be able to say, No WE suffered the most. “It's not about who suffered the most; everybody needs to be heard.” She believes that we have to remember the past, but to listen and acknowledge each other in order to make a common cause. “We can't just sit in our corners and hate each other generation after generation.”

“Jewish and ethnic Lithuanian cultures lived side by side for many years and absorbed something from each other,” says Cassedy. “What I would like to see is a proud Lithuania, but one that is open to a multiculturalism.” Šepetys echoes that sentiment, “Lithuania is a small country, but it can teach the world large lessons of peaceful endurance, and the miraculous nature of the human spirit.” She says that even though Lithuania is defined by its past, it must look toward the future.

Šepetys studied at Hillsdale college with Dr. Aleksandras Štromas, a prominent Jewish-Lithuanian political scientist and dissident. “He said it's hard to dissect the situation because there is so much overlapping, it's not clear-cut. You can't just point a finger.” Her goal in writing her book was to give people the opportunity to learn about something they might not otherwise learn about. Recently, she was in a school to give a talk and a student said to her, “I knew you were coming, and I looked up Lithuania last night, and you have some really great basketball players!” Šepetys adds, “I'm so happy that people look it up, and know where it is on a map.”

“I do feel a real connection to the people who are going to shape the future of Lithuania, and I feel myself to be one of those people, in a way that I didn't,” explains Cassedy. “It's not my country really. But I'm a sympathetic and interested observer.”

Šepetys says she has a sense of gratitude and patriotism to Lithuania. “I feel so proud to be Lithuanian, I have so much respect for [them], as I've said these people are so patriotic, selfless, generous, courageous, and I aspire—they're like superheroes to me. I'm so proud to be able to carry a Lithuanian name.” About her role as a Lithuanian-American author she says, “I would really hope that Lithuanian-Americans first and foremost help with a very simple thing, which is an awareness of Lithuania.”

Cassedy is hopeful that Lithuania is opening up to a part of its history, which is not only the friction of different peoples living there, but also the possibility that they can enjoy their differences and appreciate each other. I asked her if she knew that her great-grandfather and Šepetys's grandfather hailed from the same region, “I didn't know that!” She laughs, “You know, it's probably like, our relatives brushed shoulders in the marketplace.”

We Are Here is a first person memoir about Cassedy's journey to discover her Litvak heritage while studying Yiddish at Vilnius University. |

Between Shades of Grey is a young adult fiction novel about a 15-year-old girl who is deported to Siberia along with her mother and younger brother. |

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - (1) Comment

“Why do you love

Jews so much?”

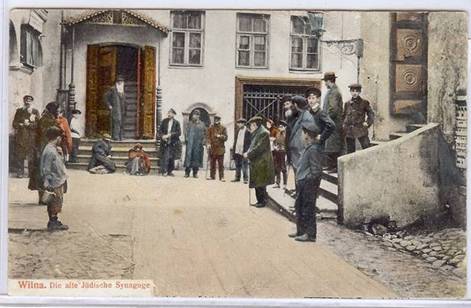

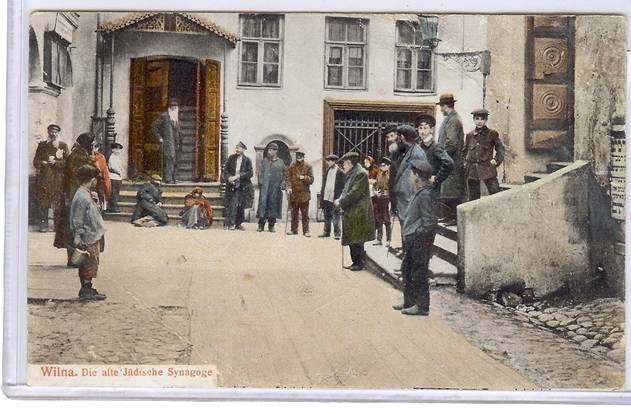

Vilnius, the old Jewish Synagogue.

By Aage Myhre, Editor-in-Chief

aage.myhre@VilNews.com

I have repeatedly been asked, by Lithuanians and others why VilNews, and I as a Norwegian without a single drop of Jewish blood, love Jews so much? Recently I met a Lithuanian-American, well educated and well read, who yet bombastically trumpeted. "You lick the asses of the Jews, Aage."

During my meetings with Jews in South Africa, where 90% of the Jewish population of almost 100 000 are of Lithuanian descent, I have also been asked why I have such great interest in Litvaks.

My answer to all these, has been that I do not love Jews more than other peoples.

But I also tend to add that I am always impressed by people who achieve more than the common herd. Intelligence and wisdom are to me among the most important qualities a person can have, and I have no problem admitting that these are qualities I've seen a lot of among the Jews I have known through life.

As to the Litvaks, they were subjected to an almost total extinction here in Lithuania during the Holocaust. It was an assault and a genocide of an unimaginable scale that we must never forget, and which memory must find its fair balance in the mental as well as in the practical.

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

“Why do you love Jews so much?”

- Posted by - (14) Comment

Vilnius, the old Jewish Synagogue.

By Aage Myhre, Editor-in-Chief

aage.myhre@VilNews.com

I have repeatedly been asked, by Lithuanians and others why VilNews, and I as a Norwegian without a single drop of Jewish blood, love Jews so much? Recently I met a Lithuanian-American, well educated and well read, who yet bombastically trumpeted. "You lick the asses of the Jews, Aage."

During my meetings with Jews in South Africa, where 90% of the Jewish population of almost 100 000 are of Lithuanian descent, I have also been asked why I have such great interest in Litvaks.

My answer to all these, has been that I do not love Jews more than other peoples.

But I also tend to add that I am always impressed by people who achieve more than the common herd. Intelligence and wisdom are to me among the most important qualities a person can have, and I have no problem admitting that these are qualities I've seen a lot of among the Jews I have known through life.

As to the Litvaks, they were subjected to an almost total extinction here in Lithuania during the Holocaust. It was an assault and a genocide of an unimaginable scale that we must never forget, and which memory must find its fair balance in the mental as well as in the practical.

On 4 April, the United States and many other countries welcomed the decision of the Government of Lithuania to appoint a fund for Jewish property compensation, calling it an important historical step toward justice.

“This law is an important step towards the restoration of historical justice and reconciliation. We welcome these and other Lithuanian Government’s steps evaluating the legacy of the Holocaust”, the U.S. ambassador to Lithuania, Anne E. Derse, said in a statement.

The Cabinet of Minister’s decision was also praised by the special U.S. envoy on issues of anti-Semitism, Hannah Rosenthal, who said that the United States supports Lithuania’s efforts to “evaluate the complex history of the period, and the commitment to fully implement the legal framework on compensation.”

I agree with both ladies. This was a step in the right direction in terms of the relationship between the Lithuanian Jews, and what once was their beloved homeland.

Then there are Litvaks who seem to blame Lithuania and Lithuanians for everything that happened here during the Holocaust. In the Baltimore Sun this week, as an example, Olga Zabludoff writes that “Lithuania tries to whitewash its role in the Holocaust.” This in response to the Lithuanian government’s decision to establish the mentioned fund.

Usually I tend to have great respect for Olga Zabludoff’s opinions, but in this case, she goes too far. There must be limits to how much one should scorn and distrust a country and its leaders for everything they do.

Fortunately, there are also many moderate Litvaks. Ellen Cassedy in Washington and Irena Veisaite here in Vilnius are good models in this respect. Feel free to read my interview with Dr. Veisaite, here https://vilnews.com/?p=2595

The problem I see is that there is still a considerable gap between Litvaks and many of today's ethnic Lithuanians, as I have described above. It seems that many on both sides do not want peace and reconciliation. They do not like each other, simply, and seems to be more interested in finding errors than points of light. Such behaviours do not build bridges or enhance reconciliation. Perhaps it’s now time for both sides to become more friendly and forgiving towards each other?

Unfortunately, Lithuania is today a poor country, and to pay $ 50M is a tremendous burden on a people who are struggling more than most in Europe, but fortunately this is balanced to a very large extent by the huge, annual support

payments from the EU, Switzerland and Norway.

Germany still pays, even today, more than 60 years after WWII, in an exemplary manner for the Nazi atrocities against Lithuania and the Jewish population here. Unfortunately, there is no sign that Russia will ever do the same, for the colossal atrocities they committed against Lithuanians during and after the war. Those who lost loved ones in Siberia or in the huge bloody guerrilla warfare that went on here for 10 years after the war, will never get any compensation, I'm afraid.

My first encounter with a Jew, in the spring of 1959, took place far north in Norway

The small farm I grew up on is located on the island Senja, far north in Norway. It was by far the smallest in my native village. But my father had always collected books. Lots of books. Good books. So our little house had shelves with books from cellar to attic. And I had early thrown myself into the reading of them all, so even though we were poor materially, I felt that we were rich in many other ways.

My first trip out from the island occurred in 1959, when I was six years old, and my father and I went to the nearest small town, Harstad, with the local boat an early spring morning. What an experience! We did our first stroll around in the town so my father could do his errands. Then he took me to a cafe. What a fantastic experience! Meatballs and mushy peas as main course and blueberry porridge with cream for dessert!

In the afternoon we came to a green house in the middle of the town. "Men Outfits" was written on a large sign above the entrance door to the shop which formed the ground floor. But it was not there my father steered us. He took me up a small outdoor concrete staircase to a door on the side of the green building. There, he pressed a button.

I had obviously never seen or used a bell, so in my curious enthusiasm, I did as my father had done: - I pressed the button next to the door so fast that my father did not manage to stop me in time. He took my hand brusquely away from the call button. Then we heard steps. Heavy steps coming slowly down the internal stairs, a staircase we still could not see.

The door opened, and two good friends embraced each other. My strict Christian father and Polish-Jewish Meyer Sokolsky very much enjoyed the reunion and meeting there at the doorway to this green house in the middle of Harstad.

It smelled smoke all the way down to the entrance. The room we soon come up to was heavily fogged by smoke from pipe and cigarettes.

But what a dream of a room! Filled with books from floor to ceiling. Books on tables and chairs. Books everywhere.

I thought I had come to paradise. My first encounter with a Jew had become a reality...

The farm I grew up on is located on the island Senja, far north in Norway. It was by far the smallest in my native village.

But my father had always collected books. Lots of books. Good books. So our little house had shelves with books

from cellar to attic. And I had early thrown myself into the reading of them all, so even though we were poor

materially, I felt that we were rich in many other ways.

Photo, by Hugo Løhre, of my tiny home village, Olaheim.

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - (0) Comment

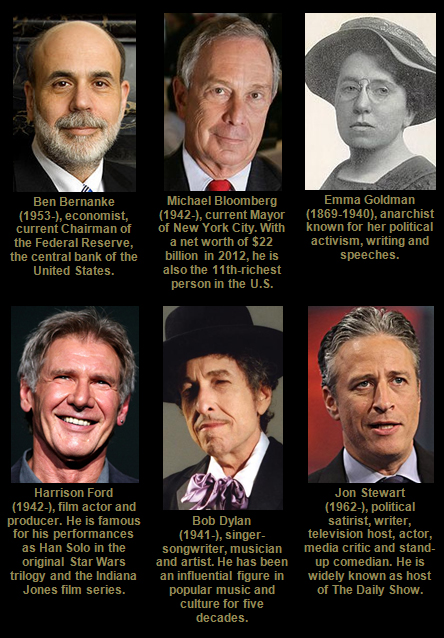

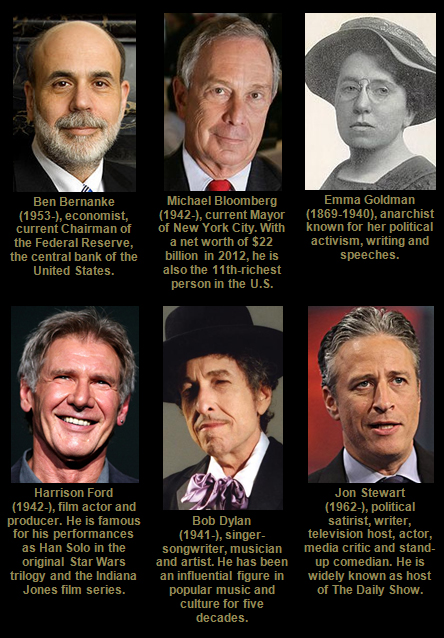

US-Lithuanian Jews

play many key roles

There are very strong communities of Jews of Lithuanian descent (Litvaks) around the world, especially in Israel, the United States, South Africa, Zimbabwe, Brazil and Australia.

In all these countries they hold top positions in politics, economy, science, culture and society in general.

Their names are frequently found among the Nobel laureates and in many other honorable contexts.

They often lead in matters and innovations that affect and influence us all, wherever in the world we live.

So also in the U.S., where they have been prominent leaders in economics, science and culture since the 1800s. It is, for example, said that Hollywood would not have existed had it not been for the Litvaks.

Litvaks are Jews with roots in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania: (present-day Lithuania, Belarus, Ukraine, and the northeastern Suwałki region of Poland).

Lithuania was historically home to a large and influential Jewish community that was almost entirely eliminated during the Holocaust. Before World War II there were over 110 synagogues and 10 yeshivas in Vilnius alone. Before World War II, the Lithuanian Jewish population was some 160,000, about 7% of the total population. Vilnius (then Wilno in the Second Polish Republic) had a Jewish community of nearly 100,000, about 45% of the city's total.

The reason for the Litvaks’ huge success is likely to be found in the fact that Vilnius through many centuries was considered the Jewish intellectual and cultural capital, with a huge number of teachers and scholars who taught and ruled this tiny community with wisdom and deep knowledge about a large number of disciplines.

Tolerance and interpersonal respect was also a hallmark of this community and for the whole of Lithuania through hundreds of years.

It was this that made Napoleon to name Vilnius as "Jerusalem of the North" when he came here on his way to Moscow in 1812. It is said that Napoleon himself became very surprised on what met him in Vilnius, a city so far away from the European mainstreams and still with a lively Mediterranean mood and life.

Vilnius was the first and only "Jewish city" Napoleon would ever see. He was no doubt aware of the Crusades, Inquisitions, pogroms and laws designed to discourage Judaic life. But here he had found a city, right before his eyes, that was an amazing exception to the rule.

And true enough, the history of the Litvaks is unusual and surprising. It was a history of mostly peaceful coexistence with other peoples and cultures that lasted for more than six centuries. It was a history that spawned an incredible number of eminent Jews, not the least of whom was Elijah ben Solomon Zalman (1720-1797), also known as “The Gaon of Vilnius”.

The "Golden Age of Jewry" in Lithuania started with Grand Duke Gediminas (1275-1341), the empire builder who took a liking to foreigners and Jews whose skills and education were badly needed in medieval Lithuania. In the early 1300's he attracted them to his realm with numerous perks, including guarantees of religious freedom and tax exemptions.

The Jews of Europe responded in droves, and Vilnius became the heralded centre of Jewish culture and learning. There would be synagogues, schools, theatres, publishing houses and the Yiddish Institute of Higher Learning. At a time when others in Europe were effectively illiterate, all the Jews in Vilnius could read and write.

This was so unusual that it provoked the invention of a brand-new word, "Vilner," meaning "an educated man with knowledge." For almost 700 years, the Litvaks became an inseparable part of Lithuanian society, having enriched the country’s economy, culture, science, and education.

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - (0) Comment

US-Lithuanian Jews

play many key roles

There are very strong communities of Jews of Lithuanian descent (Litvaks) around the world, especially in Israel, the United States, South Africa, Zimbabwe, Brazil and Australia.

In all these countries they hold top positions in politics, economy, science, culture and society in general.

Their names are frequently found among the Nobel laureates and in many other honorable contexts.

They often lead in matters and innovations that affect and influence us all, wherever in the world we live.

So also in the U.S., where they have been prominent leaders in economics, science and culture since the 1800s. It is, for example, said that Hollywood would not have existed had it not been for the Litvaks.

Litvaks are Jews with roots in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania: (present-day Lithuania, Belarus, Ukraine, and the northeastern Suwałki region of Poland).

Lithuania was historically home to a large and influential Jewish community that was almost entirely eliminated during the Holocaust. Before World War II there were over 110 synagogues and 10 yeshivas in Vilnius alone. Before World War II, the Lithuanian Jewish population was some 160,000, about 7% of the total population. Vilnius (then Wilno in the Second Polish Republic) had a Jewish community of nearly 100,000, about 45% of the city's total.

The reason for the Litvaks’ huge success is likely to be found in the fact that Vilnius through many centuries was considered the Jewish intellectual and cultural capital, with a huge number of teachers and scholars who taught and ruled this tiny community with wisdom and deep knowledge about a large number of disciplines.

Tolerance and interpersonal respect was also a hallmark of this community and for the whole of Lithuania through hundreds of years.

It was this that made Napoleon to name Vilnius as "Jerusalem of the North" when he came here on his way to Moscow in 1812. It is said that Napoleon himself became very surprised on what met him in Vilnius, a city so far away from the European mainstreams and still with a lively Mediterranean mood and life.

Vilnius was the first and only "Jewish city" Napoleon would ever see. He was no doubt aware of the Crusades, Inquisitions, pogroms and laws designed to discourage Judaic life. But here he had found a city, right before his eyes, that was an amazing exception to the rule.

And true enough, the history of the Litvaks is unusual and surprising. It was a history of mostly peaceful coexistence with other peoples and cultures that lasted for more than six centuries. It was a history that spawned an incredible number of eminent Jews, not the least of whom was Elijah ben Solomon Zalman (1720-1797), also known as “The Gaon of Vilnius”.

The "Golden Age of Jewry" in Lithuania started with Grand Duke Gediminas (1275-1341), the empire builder who took a liking to foreigners and Jews whose skills and education were badly needed in medieval Lithuania. In the early 1300's he attracted them to his realm with numerous perks, including guarantees of religious freedom and tax exemptions.

The Jews of Europe responded in droves, and Vilnius became the heralded centre of Jewish culture and learning. There would be synagogues, schools, theatres, publishing houses and the Yiddish Institute of Higher Learning. At a time when others in Europe were effectively illiterate, all the Jews in Vilnius could read and write.

This was so unusual that it provoked the invention of a brand-new word, "Vilner," meaning "an educated man with knowledge." For almost 700 years, the Litvaks became an inseparable part of Lithuanian society, having enriched the country’s economy, culture, science, and education.

To read more, go to our SECTION 12

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - (0) Comment

Ona Šimaitė:

Righteous – and Human

Julija Šukys,

Author of Epistolophilia: Writing the Life of Ona Šimaitė

Julija Šukys interviewed by Ellen Cassedy

In her new book, Epistolophilia, Julija Šukys follows the letters and journals—the “life-writing”—of Ona Šimaitė (1894–1970), a Lithuanian librarian who again and again slipped into the Jewish ghetto of German-occupied Vilnius carrying food, clothes, medicine, money, and counterfeit documents. Often she left with letters to deliver, manuscripts to hide, and even sedated children swathed in sacks. In 1944 she was captured by the Gestapo, tortured for twelve days, and deported to Dachau.

Šukys beckons back to life this quiet and worldly heroine. Ona Šimaitė is a giant of Holocaust history – one of the “Righteous among the Nations” honored at the Yad Vashem memorial in Israel – and yet little known.

Julija Šukys lives in Montreal, Canada. In addition to Epistolophilia, she is also the author of Silence Is Death; The Life and Work of Tahar Djaout. Visit her website at http://julijasukys.com.

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - (2) Comment

Ona Šimaitė:

Righteous – and Human

Julija Šukys,

Author of Epistolophilia: Writing the Life of Ona Šimaitė

Julija Šukys interviewed by Ellen Cassedy

In her new book, Epistolophilia, Julija Šukys follows the letters and journals—the “life-writing”—of Ona Šimaitė (1894–1970), a Lithuanian librarian who again and again slipped into the Jewish ghetto of German-occupied Vilnius carrying food, clothes, medicine, money, and counterfeit documents. Often she left with letters to deliver, manuscripts to hide, and even sedated children swathed in sacks. In 1944 she was captured by the Gestapo, tortured for twelve days, and deported to Dachau.

Šukys beckons back to life this quiet and worldly heroine. Ona Šimaitė is a giant of Holocaust history – one of the “Righteous among the Nations” honored at the Yad Vashem memorial in Israel – and yet little known.

Julija Šukys lives in Montreal, Canada. In addition to Epistolophilia, she is also the author of Silence Is Death; The Life and Work of Tahar Djaout. Visit her website at http://julijasukys.com.

What led Šimaitė to become a rescuer?

This is perhaps one of the most difficult questions to answer. What leads some people to behave in one way, and others differently? Where do such convictions and courage come from?

Šimaitė rarely addressed the question of why she did what she did, perhaps because she couldn’t imagine behaving otherwise, so to her mind there was nothing to explain. She once wrote that she simply acted out of a “feeling of humanity and comradery.”

Initially, her motivations were perhaps personal: after saying tearful goodbyes to friends as they prepared to leave for the ghetto, she searched for a way to penetrate its security to visit them. Once she started to visit the ghetto regularly, her mission broadened, and she began to undertake helping anyone she could.

Šimaitė lived according to a strict moral code – she never lied, she abhorred the feeling of indebtedness or dependence, and she absolutely rejected the pursuit of wealth or material gain. This code and a strong individualism are what defined the choices she made in her life.

Šimaitė is hailed as a heroine, yet you present her as a flawed human being.

I set out to create a nuanced portrait of a woman who acted with astounding courage, but who was nevertheless human. Early in my research, I came across a letter that Šimaitė concluded by writing, “love me with all my faults.” “What faults?” I wondered, “What is she referring to?” But, of course, we all have faults. They are what make us human. Šimaitė’s deep sense of compassion and capacity for forgiveness came from her understanding of this fact.

Some say the rescuers were saints, yet we learn from your book that Šimaitė would have hated being beatified. Why?

I imagine Šimaitė found it difficult to take pride in saving those she did since so many others perished, including some people very close to her. Perhaps her acts of resistance seemed to be drops that just disappeared into a vast ocean of tragedy and cruelty.

Šimaitė was tortured and confined in the camp at Dachau, yet didn’t want to talk or write about that. Can you share your thoughts on how a person – or a nation – engages with painful memories?

Šimaitė’s experience at Dachau constitutes the great silence in her writing and life. With the exception of a handful of passing references in her letters and diaries, she breathed nothing of her time there. Though I’m no psychologist, I believe this silence is indicative of a very deep trauma. For her, Dachau marked the limit of what was sayable and writeable.

In the end I decided not to try to fill Šimaitė’s silence, but to write around it, and give an image of how her camp experiences echoed throughout the rest of her life. I suppose you could say I tried to create a kind of chalk outline of her camp experience. The book traces the limits of that experience, but doesn’t try to fill in the void. I chose to respect her right to silence, and to consider silence itself as a subject worthy of contemplation.

In your book, you say you’re engaged in a conversation with Šimaitė. Can you tell us more?

I went to the archives looking for answers to questions about the Holocaust in Lithuania – the country of my parents and grandparents – and came across an incredible and largely untouched collection of Šimaitė’s papers. I was a person with a curious skill set (knowledge of Lithuanian, French, German, Russian; training in literary criticism) that seemed perfectly matched to writing Šimaitė’s life story.

I felt as if Šimaitė had foreseen my arrival, and that she’d prepared for it by saving and archiving her papers. In undertaking the project, we entered into an agreement: in return for my telling her story, Šimaitė would answer some of the questions that had been nagging at me.

Finally, can you describe for us your connection to Lithuania?

Lithuanian was the language of my childhood. I grew up speaking the language at home in Toronto, and I learned to read and write it by attending Saturday schools. Beyond life itself, a knowledge of their language is perhaps the greatest gift my parents gave me.

I’ve been to Lithuania many times, and my relationship to that place is simultaneously one of belonging and alienation. Though I get great pleasure from speaking Lithuanian in shops and restaurants, and though I experience a sense a connection to my ancestors when I walk through the fields they once worked, I nevertheless feel that I don’t really belong there. It may be that writing about Lithuania is a way for me to work through these conflicting sensations.

Now, my relationship to Lithuania and its language is increasingly textual. Like Šimaitė, I spend much of my time alone, with books, and conversing with the dead through their writings and in my imagination.

|

Ellen Cassedy |

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - (0) Comment

Jenifer C. Dillis article:

A visit to our Homeland

through the eyes of 12 American-Lithuanian women

____________________________

Jurate Norkunas

Jenifer, you have captured not only the spirit of Lithuania in your post, but the love we Lithuanians living apart from our Homeland all over the world feel. How wonderful our parents were to fill us with such love and appreciation for their homeland. Thank you for this lovely post. Jurate Norkunas-Aukstikalnis/Boston

____________________________

Roberta

How do I explain my teary eyes to my class of 2nd graders who just returned from PE class as I finished reading this???

There are no words....ok, maybe PRICELESS...but that still doesn't do the story, the photos, the memories…

____________________________

Linas Eitmanas

Love your story and pics!

____________________________

Debbie Kimball

Thank you for sharing your story! I too want to visit my homeland, both my grandparents were from Lithuania, my cousin has visited now i want too, I just need to find the right travel companion and just do it! someday SOON!

Thank you again.

Debbie Kimball-Morrow

(Kimbaldis) (Gregavilage) (sp)

____________________________

Gaile Jucenas Callo Nolan

One of my favorite places on earth!

____________________________

Joyce Kulikowski Wehrwein

I would love to make that trip, maybe 'someday!'

____________________________

Jenifer C. Dillis

I MUST return soon...2007 was so very long ago. The 3000+ photos I had taken need some updating! :)

If anyone would like to view ALL my photos from the Trip of A Lifetime, I have them all on KodakGallery...

Just let me know...:) Aciu for allowing me to revisit my favorite far away home.

Jenifer C. Dillis

There is no "if" only a "when" to describe my return to the home I love from far away...I miss my Baltic Sea...♥

Jenifer C. Dillis

I'm packing my bags right now! Ready to take the plunge into the calm, warm waters of The Baltic...heeeeheeee:)

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

History buffs gather in Lithuania to retrace Napoleon’s disastrous retreat

- Posted by - (0) Comment

![]()

Napoleon’s soldiers at the

Vilnius’ Old Town Hall, 1812.

History buffs from the Netherlands and other European countries have gathered in Lithuania to retrace Napoleon’s disastrous retreat from Russia 200 years ago.

The enthusiasts, decked in period costumes and strolling alongside Napoleon-era carriages, attracted large crowds of onlookers Friday in the Lithuanian capital of Vilnius.

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - (0) Comment

IT’S ALL ABOUT LT-MASSACHUSETTS TODAY…

A visit to our Homeland

through the eyes of 12 American-Lithuanian women

Text & Photos: Jenifer C. Dillis

Founder/Researcher at JCD Photography

Lives in East Bridgewater, Massachusetts

From Brockton, Massachusetts

Please join me and my eight biological sisters and three nieces, as we venture to The Homeland of our four grandparents. Having grown up as “purebred” Lithuanian-Americans, we 16 siblings are gifted to have parents who share their pride with us. (We sisters left our seven brothers back in The States, while we took our trip in June-July 2007).

Please join me and my eight biological sisters and three nieces, as we venture to The Homeland of our four grandparents. Having grown up as “purebred” Lithuanian-Americans, we 16 siblings are gifted to have parents who share their pride with us. (We sisters left our seven brothers back in The States, while we took our trip in June-July 2007).

Whether it was attending Lithuanian School to attempt to learn the beautiful language, dancing as members of folk dance groups, or learning to play the Kankles, we each have a level of that same pride in our heritage. Though some of us may own more “Lietuva” souvenirs than others, we all are strong, stubborn, determined, and addicted to Kugelis!

Our journey landed us in Vilnius, where the spirits of our ancestors met us warmly. How can I possibly describe the emotion of having landed in the capital of the country we had only ever heard, or dreamed about? We walked the cobblestone streets, window-shopped for Gintaras, and some of us even ventured down alleys. We felt nothing but safe and free in OUR homeland! From the powerful presence of the free-flying flags of Lietuva, to the steeple of St. Casimir’s Church, we were “home.” The locals were familiar faces. We had seen them in our own Lithuanian parish back home.

If being a Lithuanian-American or American-Lithuanian means anything to you, I suggest and recommend a visit to The Homeland. Go shove your feet into the sands of The Dunes, search for that one piece of amber along the rough shores. Pull up a chair at a local bar, and order a round of Svyturys for the crowd. Search the birth records of your ancestors. Touch the doorknob of the Church that your own grandmother may have touched. Look up while walking the cobblestones of Vilnius. Chances are there will be someone on a balcony. And that someone may be your own flesh and blood.

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - (14) Comment

A visit to our Homeland

through the eyes of 12 American-Lithuanian women

Text & Photos: Jenifer C. Dillis

Founder/Researcher at JCD Photography

Lives in East Bridgewater, Massachusetts

From Brockton, Massachusetts

Please join me and my eight biological sisters and three nieces, as we venture to The Homeland of our four grandparents. Having grown up as “purebred” Lithuanian-Americans, we 16 siblings are gifted to have parents who share their pride with us. (We sisters left our seven brothers back in The States, while we took our trip in June-July 2007).

Please join me and my eight biological sisters and three nieces, as we venture to The Homeland of our four grandparents. Having grown up as “purebred” Lithuanian-Americans, we 16 siblings are gifted to have parents who share their pride with us. (We sisters left our seven brothers back in The States, while we took our trip in June-July 2007).

Whether it was attending Lithuanian School to attempt to learn the beautiful language, dancing as members of folk dance groups, or learning to play the Kankles, we each have a level of that same pride in our heritage. Though some of us may own more “Lietuva” souvenirs than others, we all are strong, stubborn, determined, and addicted to Kugelis!

Our journey landed us in Vilnius, where the spirits of our ancestors met us warmly. How can I possibly describe the emotion of having landed in the capital of the country we had only ever heard, or dreamed about? We walked the cobblestone streets, window-shopped for Gintaras, and some of us even ventured down alleys. We felt nothing but safe and free in OUR homeland! From the powerful presence of the free-flying flags of Lietuva, to the steeple of St. Casimir’s Church, we were “home.” The locals were familiar faces. We had seen them in our own Lithuanian parish back home.

If being a Lithuanian-American or American-Lithuanian means anything to you, I suggest and recommend a visit to The Homeland. Go shove your feet into the sands of The Dunes, search for that one piece of amber along the rough shores. Pull up a chair at a local bar, and order a round of Svyturys for the crowd. Search the birth records of your ancestors. Touch the doorknob of the Church that your own grandmother may have touched. Look up while walking the cobblestones of Vilnius. Chances are there will be someone on a balcony. And that someone may be your own flesh and blood.

From faded wooden houses to the halls and courtyards of Vilnius University, the oldest university in Eastern Europe, we traveled as eager students for our guide.

We spent some time cringing as we walked the halls of the KGB “museum.” The most heart-breaking photos were those of the orphans. What shocked, and sickened me most, was the fact that up until August 1991, that building had been “in use.” I took many photos in there, but choose to not share such memories.

The Villagers of Zervynos preserve old traditions, and their own way of life. As we walked, we witnessed a gathering of the villagers. They were sadly heading toward the cemetery. What caught my eye was the woman carrying her purse!?! WHY would she need her purse in the cemetery, in the middle of the woods, in an isolated village?!? We spent a day there eating food prepared just for us. And we were entertained by our own private singers who had to endure the hottest of July afternoons while in full ethnic costume. One particular singer was so smiley with her direct eye contact. We did not understand a single spoken word, and we all got along wonderfully!

We toured Trakai Castle and Old Kaunas for some window shopping down medieval streets. The Gintaras shops caught our attention everywhere we went! Not one of us left Lietuva without a new piece of jewelry. The flower-draped balconies clung to the colorless buildings, and the people seemed to be neither rushed nor bothered by 12 American women taking over their quiet streets.

Yet another happening which struck a chord with me, was witnessing The Flag Women of Kaunas! I spotted a Lithuanian flag hanging in a non-traveled backside of buildings. I took a picture of it from my hotel room because THAT alone was very encouraging, moving, emotional to know SOMEBODY hung that there where no one would really even SEE it. It seemed done more for PRIDE! While walking that morning, we spotted The Flag Women actually going around with bundles of flags, and placing them up all over the buildings.

We asked our tour guide ahead of time, to help us find our grandparents’ places of birth. We DID find Zasliai, and felt the instant spirit of our departed grandmother. “The Church on The Lake” was still standing, as it had been in her stories to our Dad. We sisters stood on its huge steps, and touched its red bricks…for Dad.

We visited Church after Church, ate fabulous meals, drove kilometer after kilometer, and found ourselves thirsty for a beer!!! We discovered The Svyturys Brewery in Klaipeda, and indulged properly.

Neringa was our next destination. If I followed the story correctly, Neringa was a “giant” who carried sand in her apron to form the Curonian Spit to protect the Fisherman’s Village, etc from the waves of the crashing, rough waves of The Baltic Sea. There can be not the proper words written to express the sensations I felt just knowing I would soon be at The Baltic Sea. This was a dream trip come true! Who would be the first to find a washed-up piece of amber? The Curonian’s huge, blank sand dunes and forests make it a very unique and enchanting place to visit.

Somewhere in there, there MUST be at least one piece of amber…J

Off the beach, and up to The Dunes on the lagoon’s side of The Spit.

We visited Churches, shopped many more Gintaras shops, heard more stories of horror lived out by many Lithuanians, drank a few more glasses of Svyturys, cried a few more tears as we missed our loved ones back home, bonded as only sisters and nieces could, ate more delicious REAL Lithuanian foods, eventually figured out the conversion of Litas and American Dollars, had the rare opportunity to practice reciting The Lord’s Prayer IN LITHUANIAN during an impromptu Baptism invitation, visited MORE Churches, knocked on the workshop door of a local woodcarver, and arrived at The Hill of Crosses.

I remember the tears of sadness and ethnic pride in our Dad’s eyes, as we told him that we “Dillis Girls” left a cross on The Hill. Our Mother always used to admit being “a stubborn Lithuanian,” and no place proves the value and strength of stubbornness, more than the earlier days of The Hill. The courage of the Lithuanian rebels and pilgrims against the militia and KGB stood strong then.

May the future Lietuva hold for those, what it held for us 12 visitors: pride, hope, strength, determination, and a sense of bonding to see through struggles and obstacles.

If being a Lithuanian-American or American-Lithuanian means anything to you, I suggest and recommend a visit to The Homeland. Go shove your feet into the sands of The Dunes, search for that one piece of amber along the rough shores. Pull up a chair at a local bar, and order a round of Svyturys for the crowd. Search the birth records of your ancestors. Touch the doorknob of the Church that your own grandmother may have touched. Look up while walking the cobblestones of Vilnius. Chances are there will be someone on a balcony. And that someone may be your own flesh and blood.

|

Wish we could do it all again! |

|

|

|

|

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

Lithuania Hall, Brockton, Massachusetts, 1913

This article was written by JOHN BERNOTAVICZ, BS, MS, PhD (1913-2009) for Lituanus (Lithuanian quarterly journal of arts and sciences) in 1990

On Sunday, April 24, 1988, l drove from Hyannis to Plymouth to pick up Mrs. Florence Melevsky, my sister-in-law, so we could attend the 90th anniversary for St. Rocco-St. Casimir Parish in Brockton. Originally, all we had was a basement church, as l remember it. Now, over the basement towers a huge bell-towered edifice.

The following credentials will establish my family and my roots in this parish.

My father, Mykolas Juozas Bernotavicius from Marcinkonys, Lithuania, was married on June 1, 1905, to Ona Geceviciute from Varėna, Lithuania, by Father M. Peza in the old wooden church on Webster Street. Later, this building became our church hall. Although my parents had four children, l was the only one to survive beyond infancy. Because my birth occurred on St. John's Day, June 24,1913, l was baptized John. On June 11, 1939, l married Amelia Veronica Jermolaviciute (the youngest of seven sisters) in this basement church by Father John Svagzdys. Our two children, John (a graduate of Notre Dame University and Georgetown Law School) and Mary (a graduate of the Georgetown School of Nursing) were christened here in 1943 and 1946, respectively. In addition to the above data, my parents and my wife were buried from this church.

As we descended the steps to the hall, a flood of memories of long ago surged through my mind. Nowhere in sight did l see the confessionals, nor the organ or choir loft, nor any pews or stations of the cross, nor any main altar with two side altars—only a huge expansive area filled with long tables and chairs prepared for a family-style feast for the parishioners and friends of the parish. At one end we saw an hors d'hoeuvres table. Other tables along the sides of the building were lined with pictures, photos, newspaper clippings of past functions, mementoes of other activities and paraphenalia illustrating past history of its parish and people.

During the 1920-1935 era, Brockton, a bustling city of 55,000-65,000 inhabitants, was known as the world's largest shoe manufacturing center.

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

Lithuania Hall, Brockton, Massachusetts, 1913

This article was written by JOHN BERNOTAVICZ, BS, MS, PhD (1913-2009) for Lituanus (Lithuanian quarterly journal of arts and sciences) in 1990

MY SALUTE TO THE LITHUANIANS OF BROCKTON, MASSACHUSETTS

JOHN BERNOTAVICZ, BS, MS, PhD

On Sunday, April 24, 1988, l drove from Hyannis to Plymouth to pick up Mrs. Florence Melevsky, my sister-in-law, so we could attend the 90th anniversary for St. Rocco-St. Casimir Parish in Brockton. Originally, all we had was a basement church, as l remember it. Now, over the basement towers a huge bell-towered edifice.

The following credentials will establish my family and my roots in this parish.

My father, Mykolas Juozas Bernotavicius from Marcinkonys, Lithuania, was married on June 1, 1905, to Ona Geceviciute from Varėna, Lithuania, by Father M. Peza in the old wooden church on Webster Street. Later, this building became our church hall. Although my parents had four children, l was the only one to survive beyond infancy. Because my birth occurred on St. John's Day, June 24,1913, l was baptized John. On June 11, 1939, l married Amelia Veronica Jermolaviciute (the youngest of seven sisters) in this basement church by Father John Svagzdys. Our two children, John (a graduate of Notre Dame University and Georgetown Law School) and Mary (a graduate of the Georgetown School of Nursing) were christened here in 1943 and 1946, respectively. In addition to the above data, my parents and my wife were buried from this church.

As we descended the steps to the hall, a flood of memories of long ago surged through my mind. Nowhere in sight did l see the confessionals, nor the organ or choir loft, nor any pews or stations of the cross, nor any main altar with two side altars—only a huge expansive area filled with long tables and chairs prepared for a family-style feast for the parishioners and friends of the parish. At one end we saw an hors d'hoeuvres table. Other tables along the sides of the building were lined with pictures, photos, newspaper clippings of past functions, mementoes of other activities and paraphenalia illustrating past history of its parish and people.

During the 1920-1935 era, Brockton, a bustling city of 55,000-65,000 inhabitants, was known as the world's largest shoe manufacturing center. Most of the parishioners of St. Rocco worked in such factories as W.L. Douglas, E.E. Taylor, Geo. E. Keith, Diamond Shoe, Field and Flint, etc. Their buildings covered blocks and blocks of acreage and thousands and thousands of people were employed therein.

The Montello section of the city is located in the northeastern end of town. This "village" as we called it was the principal home of most of the parishioners. It was about two miles from the only high school we had and from the center of the downtown section.

All of my youthful activities centered around the church, the hall and the ward six playground next to the hall. l remember the beautiful religious processions, the festivals, the plays put on by the children of Mary, the choir participation, the musicals and the Saturday movies in the hall. The area around the hall seemed to be the starting point for parades, church festivals, for rides to the church owned Romuva Park, etc.

l recall the Franklin Grade School not far from the church where a tow-headed, blue-eyed youngster being led to Miss Clark's first grade room by his mother and being told "Būk geras vaikelis" (be a good child) in Lithuanian. Almost all of my classmates spoke Lithuanian only, except for what English we picked up at the playground from older kids.

My small world was filled with private homes and three-decker apartments, small businesses and stores of all types. Brockton was bisected by the South Shore Railroad to Boston (as was our village). The trolley line from downtown ran down Ames St., Intervale St, Bellevue Avenue and ended on Sawtelle Avenue to carry workers to the various shoe factories. Of course, the trolley was also our way of getting to high school. I recall how adept some of us got at opening the back door of the car to let non-paying students hop in.

One other point about our village was its proximity to the ward six playground with its swings, baseball diamond, etc. This was my entry to the sport of baseball. Years later, I became the playground supervisor during my college years.

The village seemed to be full of Lithuanian merchants catering to the tastes and needs of their compatriots. Those I remember with much affection are:

1. Bakers: Suppliers of rye and raisin breads, prepared food for weddings, Thanksgiving, Christmas and even for post-funeral affairs.

Radauskas, Kilkus, Duoba and Wallen Bakers.

2. Grocery stores-meat markets: Sold home made kilbasa and kopusta, pickled herring and horseradish, etc.

Abracinskas, Balchunas, Axtin, Belkis. Bellevue Ave. Bucys, Gaigal, Kaslauskas, Kodis, Moncevich, Sviokla, Uozis, Vismantas, Yukna and Zinkevicz Markets.

3. Pharmacies and drug stores: Kvaraceus, Miskinis, Visman and Walangevich.

4. Dry goods, furniture, shoes, post office: Kaseta, Paulauskiene, Pranaitiene and Stasys Grigus, Karzis, Mickevich, Mickevich.

5. Miscellaneous Businesses: Cafés and restaurants, candy stores, cobblers and plumbers, Godfrey coal and grain, Germanavicius Barber Shop, funeral home, Kasper's pool hall-bowling alleys, Matulis printing shop, several social clubs, Yakavonis bath house.

Certainly this is an impressive listing suggesting a rather self-contained and self-sufficient community.

Lithuanian was spoken and understood in any of these establishments. It occurs to me that Ed Cassidy, the patrolman on the beat, knew many basic Lithuanian phrases and terms. Many years later, Lithuanian names showed up on the rolls of the police dept., fire dept., as teachers in schools, in politics and also as small manufacturers.

As the banquet droned on with its splendid speeches and musical interludes and presentation by his honor the mayor of Brockton, Carl Pitaro, more memories flashed through my mind's eye.

In 1917, World War l was still raging in Europe and l recall a visit from my uncle Peter Chestnut to bid us farewell before being shipped to France. He arrived with a huge rifle and in uniform. For our edification, he fixed a bayonet to the rifle and proceeded to show us "present arms." Noting a child's interest in the rifle, he asked me whether l would like to perform the same maneuver. Naturally, my trial was a colossal and stupendous failure. The heavy rifle knocked me on my butt and fell across my little body. The result was a screaming, crying, frightened four-year-old child!

l was 10 years of age in 1923, and received my first communion from Father John Svagzdys in our basement church. Immediately after the service, we hurried across the street to the professional photographer to have my picture taken with my new knickers—and new Converse sneakers!

It was in this parish that l had my first exposure with death. My childhood buddy, Ralph Willen, had been shipped to Colorado to recover from tuberculosis. One year later, they returned him in a pine box. His grandmother asked me to be one of the pall bearers. She lived in a three-decker apartment and Ralph was waked there. This handsome giant, over six feet tall, had to be toted down three floors of rather narrow, winding stairs to the hearse on the ground floor. We arrived safely and were relieved that no accident had occurred!

How can I forget the cold Easter morning services when my family trudged through, down the Ames Street Hill, to the church. Occasionally we would have drifts of snow as high as the roof of our one-level church building.

Of course, I remember the church pageants in which parishioners dressed as Roman soldiers to guard the tomb of Jesus Christ. Nor can I fail to recall how frightening it was for a child to sit through the Lithuanian missions and listen to sermons filled with hell-fire and damnations being bellowed at me by Father Chaplickas from Chicago, III. No place to run and hide oneself except under the wing of one's parents.

Then I recall what a pleasant treat it was to go to the Saturday afternoon movies in the church hall. Here we saw all the silent stars like Tom Mix, Wm. S. Hart, Hoot Gibson, Charley Chaplin, Fatty Arbuckle, Tarzan, Pearl White, Mary Pickford, etc. During these shows, piano music was provided by Adolph Krush or Frances Kaseta. l considered it to be quite an honor to sit up front and turn their pages. Meanwhile, up in the balcony, the young generation was holding hands and smooching with their girl friends. 0, yes, we had proctors upstairs.

Each Saturday morning, we would go to Lithuanian classes to be able to read and write the language. I still have the certificate indicating that I had acquired these prerequisites.

The parish owned a lovely acreage a couple miles away which was called Romuva Park. Events here were quite varied from sports, to dancing, to huge picnics at which hundreds of Lithuanians from surrounding parishes would spend the day celebrating holidays and feast days. One of the outstanding features here was the clay tennis courts. Many a game did Brony Bartkevicz, Bennie Yezukevich, Ernie Yukna and I have here. Of course we played baseball here also. Not the least interesting was the fact that we learned Lithuanian and American dances here, under the tutelage of Frances Galinsky, Vincenta Treinavich, Florence and Amelia Jermolavich and others. I must mention that Paul Sakas and his brother John were two of the better New England tennis players in this era. Paul, of course, became our choir director.

Another treasured experience took place while Father Kneizys was our curate. He had a wonderful facility for translating and transposing American songs, operas, musicals, etc., into Lithuanian. After adequate practice and training, his cast would take these shows on the road to other parishes like Norwood, Stoughton, Cambridge, South Boston, Lowell, Lawrence, Hudson, etc.

Being asked to join the senior choir at the age of 16 was certainly a wonderful memory and honor. Our choir directors were all interesting people. Messrs. Banys, Burke and Sakas did yeoman service for this parish. They kept us a closely knit as a group at picnics to such places as Mayflower Grove in Bryantville and Nantasket Beach. Mr. Burke would hire a symphony orchestra and soloist to assist us when we performed "The Seven Last Words of Christ."

Paul Sakas, our local boy, entered our chorus in a New England songfest held at the symphony hall in Boston. Competition was against some of the best professional chorus groups around, something rather incredible occurred when the "kids" from the village came in first! l remember the phonetic melody "Dzimdzi Drimzi" did the trick as our final song. Wonder what ever became of the trophy?

Because our church hall was adjacent to ward six playground, we spent lots of time here. l played for the under-16-years-old team and we won our league many times. Years later, after passing an exam, l became a playground supervisor (as did Virginia Pekarski).

One day, Peter Couble asked me to play for St. Rocco's Baseball Team. Long before l joined, St. Rocco's had their own "Charley Hustle" or Ty Cobb in the person of Frank Couble. He fought for everything and anything whether it was a stolen base, close pitch or a fielding call. When he slid into a base, he came at you with spikes flying. He backed down to no one despite his small stature. This team had a great group of athletes. I recall pitchers like Dom Bartkus, Peter Pieski, Peter Chestnut and even me, catchers like J. Chestnut, J. Kvaraceus, W. Melesky, F. Svirsky, M. Yakavonis, J. Petkunas, A. Couple, J. Tamuleviches and A. Snyder. We would play anyone including, K. of C. teams and town teams from Hanson, Hanover, Whitman, Stoughton, Plymouth, Sandwich, and even Providence R.l. My highlight was pitching against the House of David from Benton Harbor, Michigan. Their team was composed of old timers from the major leagues. In spite of pitching an eight-hit game, we were beaten 2 to 0.

Education was a very important cog in my life and the life of my family. My dad got his sixth-grade certificate from Franklin School before he obtained his citizenship papers. Because he could read and write in Lithuanian, English, Polish and Russian, my mother would always tell me there was no need for her to acquire these talents. Much later, when her Mykolas died, with lots of sweat and tears and persistence, she learned to write her name at the age of 55.

My own Brockton High School Class of 1931 enrolled a total of 866 students in the freshman class and after four years, we graduated 433. In this graduating class, l found a total of 36 Lithuanian names on the final roll.

Realizing that these were the depression years, this was an outstanding honor for the parents of this parish.

To illustrate the esteem our folks had for knowledge and education, l will attempt to recall the people l knew who went to college, graduate schools, etc.

l beg the indulgence of those whom l may have missed, for any errors and omissions l have made, since memory often plays nasty tricks on one:

Amherst College: Julius Kastantin

Alabama, University Of: Joseph Mastovick, Joseph Miskinis

Bentley School of Finance: Walter Melevsky, Vincent Smalukas

Boston College: John Sakas, Paul Sakas, Charles Vaichulis

Boston University: Ed Abrachinskas, Dr., Elizabeth Belkis, Ann Duoba, Nellie Jermolavich, A. Mathews, Vincent Mazgelis, Emily Oksas, Julia Sviokla, Leonard Tamulevich, lawyer, John Williams

Bridgewater State College: Elaine Kamandulis, Florence Kamandulis, Julia Matulis, Lena Matulis, Virginia Pekarski, M.S. Mass State

Brown University: Adolph Sharkey, Harry Sharkey, Francisc Yukna

Burdett College: Ralph Stitilis

Canisius College: Peter Miskinis

Catholic University: Julius Stangis

Fordham University: Julius Miskinis, Michael Miskinis, Walter Uzdavinis

Harvard University: William Kvaraceus, PhD Holy Cross College: John Biaorunas, Hippolit Monkevich, Casimer Yakavonis

Georgetown University: Charles Vaichulis Northeastern University: Sylvester Sviokla

Mass. Inst. Technology: John Greze, Ed. Mickevich, Melvin Mickevich

Pierce Secretorial: Amelia Jermolavich, Alice Yakavonis

Providence College: john Bernotavicz, MS, PhD, Mass State

Rhode Island State College: Michael Grigas, John Roanowicz

School of Pharmacy: Al Miskinis, Len Vismantas, Al Walengevich

Simmons College: Ėlaine Pekarski, Bertha Bartkus

Suffolk Law: Julia Yakavonis

Tufts University: Al Budreski, doctor, Joseph Kvaraceus, doctor

Washington State College: Al Balchunas

Wentworth Institute: Joseph Ykasala

William and Mary College: Matthew Yakavonis

Yale University: Ramanauskas

U.S. Coast Guard Academy: Captain Walter Bakutis, Captain Peter Smenton (Smetonis)

U.S. Military Academy: Colonel Ralph Chesnauskas

U.S. Naval Academy: Admiral Alex Couble, Admiral Fred Bakutis, Admiral Peter Moncy (Moncevich)

In addition to the above, we had the following professional people whose affiliation I did not recall (at college or university); Dr. A. Mason, dentist; Dr. Al Waitkus, osteopathic surgeon; Dr. Al Glenn Gecevich), optometrist;

Peter Kvaraceus, lawyer,

A grand total of 30 schools from all over the United States— and all in my youthful years.

This parish was also blessed with the following children of parishioners who dedicated their lives to the religious vocations: Reverend A. Abracinskas, Reverend A. Baltrashunas, Reverend J. Kasmandulis, Reverend J. Long, Reverend J. Prusaitis, Reverend S. Saulenas, Reverend A. Sheputa, Reverend E. Sviokla, Sister M. Audyaitis, Sister A. Balberis, Sister M. Dambrauskas, Sister M. Grazevich, Sister A. Valentukevich, Sister M. Treinavich, Sister M. Tamulevich, Sister M. Zemeikis, Sister M. Jushkaitis, Sister C. Mazgelis, Sister E. Sakas.

I am certain that there were others who started college but for one reason or another did not have the opportunity to matriculate. To each and everyone, a grand huzzah! If, as one of the speakers stated in his remarks, the religious were the stars of this parish, it is my contention that the graduates were the nova of the parish and the parents should be classed as the super nova!!

It was these parents who were the backbone of the parish and were who scrimped, saved and suffered toward the education goals for their progeny and were the ones who contributed to the parish needs.

God was good then and continues to be forever.

At last I can set aside my emotional thoughts and memories and return to the enjoyment of the food and entertainment of this banquet.

I will always wonder how many other Lithuanian parishes can match what the people of St. Rocco's-St. Casimir's has accomplished.

St. Casimir Church in Brockton closed in 2008

Over the past years, six Catholic parishes in Brockton have closed or merged, making the city one of the hardest hit by the Boston Archdiocese's reconfiguration process. In 2008 St. Casimir Church, a 110-year-old Lithuanian parish held its final service…

Read more…

___________________________________________________________________________________________________

Lithuanian Brockton disappears

Nearly a century after she was born in Brockton’s Lithuanian Village, Helen Savilonis Giovanello still remembers the aroma of Lithuanian bread baking at Kilkus Bakery. She remembers the lush flower gardens grown by Lithuanian immigrants. She remembers her family’s well-tended home at 18 Albert St. and her days at the neighborhood’s Franklin Elementary School.

But most of all, she remembers the solidarity of the people who lived in that northeast section of Brockton. “It was a cluster of Lithuanian people that were all friendly with the church,” says Giovanello, now 98.Those days are over. The Lithuanian Village is but a shadow of the once-vibrant enclave, and the expected closing later this month of the venerable St. Casimir Church may mark the end of the Lithuanian community in Brockton.

Read more…

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - (0) Comment

“I will always wonder how many other Lithuanian parishes can match what

the people of St. Rocco's-St. Casimir's has accomplished.”

St. Casimir Church in Brockton closed in 2008

Over the past years, six Catholic parishes in Brockton have closed or merged, making the city one of the hardest hit by the Boston Archdiocese's reconfiguration process. In 2008 St. Casimir Church, a 110-year-old Lithuanian parish held its final service…

Read more…

____________________________________________________________________

Lithuanian Brockton disappears

Nearly a century after she was born in Brockton’s Lithuanian Village, Helen Savilonis Giovanello still remembers the aroma of Lithuanian bread baking at Kilkus Bakery. She remembers the lush flower gardens grown by Lithuanian immigrants. She remembers her family’s well-tended home at 18 Albert St. and her days at the neighborhood’s Franklin Elementary School.

But most of all, she remembers the solidarity of the people who lived in that northeast section of Brockton. “It was a cluster of Lithuanian people that were all friendly with the church,” says Giovanello, now 98.Those days are over. The Lithuanian Village is but a shadow of the once-vibrant enclave, and the expected closing later this month of the venerable St. Casimir Church may mark the end of the Lithuanian community in Brockton.

Read more…

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - (0) Comment

Boston, Massachusetts, July 1, 2012

The 14th Lithuanian Folk

Dance Festival!

Lithuanian folk dance group of Vilnius Gediminas technical university

The Boston Lithuanian American Community will be hosting as many as 47 Lithuanian folk dance groups from around the world. The dance festival is held every four years and for the first time will be coming to Boston. The festival begins with an entry march, as 1,800 dancers dressed in distinctive folk costumes fill the stadium floor, then together perform intricately choreographed dances, creating a kalaidescope of movement, music and color.

Come experience this celebration of Lithuanian dance and culture!

Learn more at: http://www.sokiusvente2012.org/

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

VilNews e-magazine is published in Vilnius, Lithuania. Editor-in-Chief: Mr. Aage Myhre. Inquires to the editors: editor@VilNews.com.

Code of Ethics: See Section 2 – about VilNews. VilNews is not responsible for content on external links/web pages.

HOW TO ADVERTISE IN VILNEWS.

All content is copyrighted © 2011. UAB ‘VilNews’.

Click on the buttons to open and read each of VilNews' 18 sub-sections

Click on the buttons to open and read each of VilNews' 18 sub-sections

.jpg)