THE VOICE OF INTERNATIONAL LITHUANIA

|

VilNews has its own Google archive! Type a word in the above search box to find any article.

You can also follow us on Facebook. We have two different pages. Click to open and join.

|

Author Archive

The village voice…

- Posted by - (0) Comment

VilNews will from time to time publish articles under the heading 'The Village Voice'. The articles will be written by a retired Englishman, David Holliday, who for the past fifteen years has lived with his wife Migle in the village Lapiai 30 km from Klaipeda. We think that you, dear reader, will come to appreciate David's many subtle tales and stories from his life out there – so far off the beaten track...

|

Wg Cdr David Holliday joined the British Royal Air Force in 1961. He trained as a pilot and his first operational tour from 1964 to 1968 was spent flying Victor nuclear bombers carrying the American Blue Steel stand-off missile. His Cold War targets were in the Baltic States, Belarus and Ukraine. In 1968 the British nuclear deterrent was handed over to the Royal Navy and the Blue Steel fleet was disbanded. After a tour as a flying instructor David returned to Victors, but this time in the Air-to Air refuelling role, again as an instructor. This was followed by a tour in Moscow as an assistant Air Attaché (74-77). In 1979 he was posted to France to be the Strike Command liaison officer with the French Air Defence Command. The next ten years was spent in staff appointments in Human Intelligence. David’s last tour (92-94) was as the first British Defence Attaché in Vilnius after Lithuania regained its independence. He retired in 1994 and remained in Lithuania with his wife Migle, who he married in 1993. |

|

Around the castle hill

How We Found Lapiai

Part one

July 1995

My life here in Lithuania revolves around my home in the country. To many it would be a bore, but for me it is the perfect life and I could wish for nothing better. This morning, as always, I walked the dogs around the valley and, as always, Blondie ran off into the woods. I stopped off by the river to see if the overnight rain had had any effect. It had, but not much and we need more. This spring of 1995 was abnormally hot and dry and they say that there has been nothing like it since records began. Farmers have been hard hit again this year and yields all round will be very low. There are still signs of beaver activity on the riverbank and there are several dams in our stretch of river, which runs for about a kilometre. Our neighbours have erected a fence in front of their cattle fodder to stop the beavers pinching it at night. It seems to have worked for there haven’t been any raids for the last few days. I want to put a sign up on the fence saying “Beavers! Food round the back of the fence”. But Migle says that it might not go down well with Povilas, because it might work and put our friendship in jeopardy!

I normally walk the dogs all around the valley, but at this time of year the grass is very high and I get soaked tramping through it. Tomorrow (or the next day) I will go round with the trimmer and cut a swathe through it. On the way back from the river I stop off at the alpinarium for a look. Actually it’s an enormous pile of rocks, which were pulled out when we excavated the pond last year. Some of them are nearly chest height and weigh several tonnes. Together they cover an area half the size of a tennis court. In England they would cost £100 each in the garden centres. Anyway, we call it an Alpinarium as we are working towards it. Migle has planted some flowers and shrubs and it is my job to weed and to water and it’s got to be done today! Yes dear. It’s going to be another exciting day and I can’t wait to get started. But first a cup of breakfast!

Before we go on, I’d better explain how I came to be here. My last appointment in the Service was as DA in Vilnius. That was from 1992-94 when the Russian troops were still here. I worked in the MOD in London and spent about a third of my time out here. I was single at the time and met Migle. She was wheeled in as the interpreter whenever a group of Englishmen appeared in Klaipeda. She had her own business and did it as a favour to one of her army friends here.

Migle and I married at the Registry Office in Ashford in front of the home crowd on New Year’s Eve 1993. I took early retirement in March 94 and made sure that we got married before I left, for reasons which you and I know, but which Migle remains blissfully unaware of! In the meantime we bought a three room flat in the centre of Klaipeda for £8,000 and had it refurbished and modernised for about another £2,500. The flat is comfortable and right in the centre of Klaipeda next to the old town. It overlooks the river Danes and between the river and us is a park with a decorative water fountain. All very comfortable, but not much to do in the winter.

We had an artist friend we met in town and from whom I used to buy the odd piece. One day in the summer of 1995 he invited us out to his country house about 30 km form Klaipeda in the village of Lapiai. It is a lovely situation on the side of a hill. The house was being built and the foundations were in place. Meanwhile, as is the way out here, he had built the outhouse first, so they could live there while the main house was being done. He has about a hectare of land (2.5 acres), just down the slope below the village school. It was a lovely day and we sat outside and chatted well into the night. In those days I had to communicate in Russian and that made it rather difficult for the locals who all wanted to lapse into Lithuanian. I remember during the course of the evening that Migle said that we were looking for a place in the country as well. We went home and thought no more about it.

A few weeks later in early summer, Migle had a phone call. It was Vytas our artist friend. He said that there was a small farm in the village, which had come up for sale. Did we want to have a look? Did we ever! We drove out again at the weekend and parked in his drive. Vytas explained that the farm was in the valley down the hill about a kilometre further on. It belonged to an old lady whose husband had died about three years ago and who wanted to sell up.

We walked down the hill and into the valley. At first we chatted in Russian so I could join in, but quickly changed to Lithuanian as Vytautas (Vytas for short), Eugenija his wife and Migle moved ahead slightly. The first farm at the bottom of the hill has a good position within a stone’s throw of the river. I knew it wasn’t the one for sale as it was too close to the hill. We followed the river around the bend and the next farm came into sight over the growing corn. I could see several out buildings, including the large barn, some beehives and the inevitable outside toilet painted “s” brown. Again, it looked attractive, but I didn’t really think it would be the one, so I didn’t fantasise too much. Sure enough, we kept on the little road and moved on round the corner and down another rise. And there in front of us about 300 m away in the distance was this beautiful sight. The house and farm buildings stood on a knoll in the centre. The river ran some 200 m to the right. Beyond the buildings were open fields and then the castle hill dating back to the 14th century. To the left more grassland before the ground began to rise up to the woods at the side of the valley. From where we stood the house was on the right and was painted pastel green. To the front and facing towards the river there was a rickety glass conservatory covered in ivy or vines. Standing a few yards from the verandah were two magnificent old spruces and perched on top of the furthest of them was the biggest stork’s nest you have ever seen! We walked closer along the lane, which led towards or past the house. All heads were turned to take in the unfolding view. Nobody wanted to stare, but everyone wanted to look. For it was certain sure that we were being watched.

But instead of turning up the track leading to the house, the three ahead continued past the house and turned right towards the river and left the house behind us. So, I must have been wrong. This wasn’t the farm. There must be another one beyond the Castle Hill and at the very end of the valley. I tried hard not to be disappointed, but I was. Desperately.

I followed a few paces behind Migle, Vytautas and Eugenija like a Russian-speaking leper. I could here them talking and discussing, but had no idea what they were saying. We arrived at the bend of the river. It is called the Zvelsa and at this point is about six to eight metres wide. It was mid-summer and the water was running low and slow. About a kilometre further on it joins the larger Minijos, which is one of the larger rivers flowing across eastern Lithuania.

Here we stopped for what seemed an age as they chatted and I began to move ahead, impatient to see what would lie round the next bend. But when I turned back, they were gone! I rushed back to the river and saw them a little way ahead and walking back the way we had come. I ran up to them and said in English “Migle, why are we going back?” She said, “This is the house. This is the one we are coming to see!” I said, “But why did we walk past it and down to the river?” She said, “Well, we just wanted to see the view from the river and get the feel of the place and see all the land that goes with it”.

I can’t explain how happy I felt then. It was a defining moment in my life. The first date, first solo and maiden century all rolled into one! Migle said, “You stay here and we’ll go in and talk to the old lady. If she knows you’re a foreigner the price will go through the roof!”

I went back to the bend in the river and sat down on a rock by the water and listened to the music of the river and the birds. They could talk for as long as they liked. I wasn’t going anywhere! This was where I was going to live!

July 1995: I wasn’t going anywhere! This was where I was going to live!

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - (3) Comment

![]()

90% of all Jews in South Africa are Litvaks

Text and photos: Aage Myhre

For the tens of thousands Litvaks who came to South Africa during the years 1860 –

1940, the Cape Town harbour was the first glimpse they had of their new homeland.

It is considered that around 90% of the approximately 80,000 Jews living in South Africa are of Lithuanian descent (the so-called Litvaks), which thus constitutes the largest pocket of Litvaks in the world! You are hereby invited to learn more about this unique Jewish community that still holds Lithuania alive in their hearts, museums and synagogues.

The Jewish Museum in Cape Town is more Lithuanian than Lithuania itself.

The Jewish Museum in Cape Town offers visitors a journey back in time. Most museums do. The striking feature of this museum, however, is that the journey to the past also brings us to a completely different part of our world, from Africa's southern tip to a seemingly modest little country far to the north, to a country where around 90% of South Africa's Jewish population has its roots (there are today about 80,000 Jews in South Africa).

The museum's basement is dominated by a village environment (shtetl) from the late 1800s. A few houses are reconstructed in full scale, and you can clearly see how people lived and co-existed at the time. The village is called Riteve. It was recreated in the museum on the basis of entries made in the 1990s by a group of experts who went from South Africa to Lithuania to find traces of the family of the museum's founder, Mendel Kaplan.

The village is called Rietavas in Lithuanian. It is there to this day, less than a half hour drive from Klaipeda, at the highway direction Kaunas and Vilnius. The Kaplan family emigrated from here in the 1920s, while the village's population was still 90% Jewish. Today, no Jews live in Rietavas.

A stroll among the house-models in the Cape Town museum's basement is like walking around in a part of Lithuania, almost more Lithuanian than Lithuania itself. This impression is becoming no less strong when I discover that the café that is a part of this comprehensive Jewish complex in Cape Town, is also named after the founder's home town in Lithuania, and that the older part of the museum is a replica of a Vilnius synagogue. This synagogue was built in 1863, and was the first ever built in South Africa.

The museum and Café Riteve are just two of the elements of an extensive complex of Jewish-related buildings here in Cape Town's incredibly beautiful botanical garden, so if you first come here, I recommend that you take your time. Worth a visit is the Great Synagogue from 1905, the Gitlin Library (including a large collection of books in Yiddish that the Litvaks brought with them on the long sea voyage from Lithuania to Cape Town), and the Cape Town Holocaust Centre (see below).

Lithuanians dominate the Jewish community in South Africa

Lithuanians dominate the Jewish community in South Africa to an extent seen in no other country. Casino magnate Sol Kerzner (1935 - ), communist leader Joe Slovo (1926 – 1995) and veteran anti-apartheid activist Helen Suzman (1917 – 2009) make an unlikely trio but have in common that they are all of Lithuanian descent.

Like their Lithuanian ancestors, whose political ranks included wealthy capitalists, zealous Zionists, prominent religious scholars and committed communists, South Africa's Litvaks, have spanned the political spectrum. On the left stands Slovo, the former head of the South African Communist Party, who was born in Lithuania in 1926 and came to South Africa at the age of nine. On the right stands Kerzner, a flamboyant businessman who built the famous casino resort Sun City (north of Johannesburg) and founded the entertainment and leisure giant Sun International.

Jewish emigrants from Tsar occupied Lithuania are generally thought of as having fled the persecution and poverty for the safe shores of America. A much less known story is that of the many Litvaks who travelled to South Africa. Many of these migrants came from the Kaunas region (Kovno in Yiddish), but many also came from towns such as Palanga, Panevėžys, Rietavas and Šiauliai.

Many travelled via the Liepāja port in Latvia on ships bound, via the Baltic Sea and (after its opening in 1895) the Kiel Canal shortcut, for English east coast ports. From there, they travelled overland, usually via London, to Southampton to embark for Cape Town.

This movement of people was not accidental: a whole business existed to cater for them, from the ticket agents in Kaunas or Vilnius, to shipping lines such as the Wilson Line shuttling between Liepāja and Hull, to the Poor Jews’ Temporary Shelter in London which housed and orientated many of the trans-migrants, to the Castle Line and the Union Line which specialised in the route to South Africa.

And like any successful movement of people, it became self-perpetuating, as the new South Africans sent home letters, and money, encouraging others to follow suit. The first countrywide Union of South African census in 1911 indicates a population of 46,919 Jews, a majority of whom were Litvaks. By 1921, the Jewish population had risen to 62,103, but with more of a shift in gravity towards the gold-mining and commercial centres of Witwatersrand in the Transvaal area (which accounted for 33,515).

What this means is that a great many of those North Americans and British with Litvak ancestors are likely to have kin in South Africa. There are many good sources for Jewish family history research in Lithuania and prospects of success are often favourable, as long as the place of origin within the country is known or can be identified.

The extraordinary story of Sammy Marks (1843 – 1910) from Taurage

The entrepreneur Samuel Marks was born in the Lithuanian district of Taurage in 1843. He was one of the very first Litvaks to arrive on African shores. He came here via England in 1868 and began his career by hawking cheap jewellery and cutlery in Cape Town. Later he moved on to Kimberley where he went into business with his brother-in-law Isaac Lewis and Jules Porges. Together they formed the French Diamond Mining Company.

Following this, Lewis and Marks decided to relocate to the Eastern Transvaal where they established the African and European Investment Company. This company proceeded to become a major Rand finance house with controlling interests in several gold mines. Mr. Marks had become a leading magnate and one of South Africa’s richest men.

An example of his many success stories is one of the companies he started, theZuid-Afrikaanscheen Oranje Vrystaatsche Mineralen en Mijnbouvereeniging, which became the basis of the town Vereeniging. Marks also developed the Viljoen’s Drift coal mine and encouraged the expansion of the Witbank coalfields.

Sammy Marks was also a close friend and admirer of South Africa’s State President Paul Kruger (who is often called the father of the Afrikaner nation) and a popular figure within the Transvaal business community. It was Marks who advised Kruger to build a railway line from Pretoria to Lorenco Marques. He served as a senator in the Union Parliament from 1910 until his death in 1920 in Johannesburg.

Worth a visit is the Sammy Marks Museum north of Pretoria and Johannesburg. The museum building, a splendid Victorian mansion dating from 1884, was the residence of Marks, whose significant contribution to the industrial, mining and agricultural development of the Zuid-Afrikaansche Republiek has given him an outstanding position in South African history, so very far away from his birthplace in Taurage, Lithuania…

|

Click here to read more about the exceptional history of the Litvaks in South Africa : http://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/jsource/vjw/South_Africa.html

|

Some of today’s Litvaks in South Africa

Let me introduce you to some of my good friends in South Africa. Most of them are second and third generation Litvaks (plus one single first-generation Litvak). There is also a small colony of Lithuanians who have moved down here the last 20 years. My conclusion is that Lithuania and the Lithuanian spirit is alive and present, even in modern South Africa.

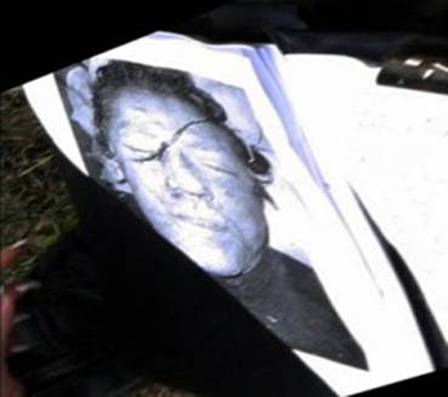

SAM (SHMUEL) KEREN

BORN IN PABRADE, LITHUANIA, IN 1934. A HOLOCAUST SURVIVOR

Sam's life story is worthy of a screenplay. His autobiographical book, 'Mulik the Zulik', says it all. Sam was the only person of his family able to escape the Holocaust in Lithuania. A Polish neighbour family acted as if he was their son and managed in this way to smuggle him out of Lithuania during the war. The rest of his family was executed. After WWII, Sam managed to get to Switzerland, and later to Israel. But it was South Africa that was to become his new homeland, in the 1960s. Here he has done well in business and private. Sam visits Lithuania and his home-place Pabradė every summer since the 1990s. He likes Lithuania, but is still sceptical of Lithuanians and their involvements in the killing of Jews during the Holocaust. I took the above photo of Sam in his office in downtown Cape Town. On the walls hangs many of the memories from his enormously challenging youth. The image he shows me is of the tombstone he installed on his mother's grave a few years ago. In Pabradė village, Lithuania.

JEANETTE JEGGER

FILM PRODUCER AND DIRECTOR. PREPARING A DOCUMENTARY ABOUT LITVAK LITHUANIA

|

|

Jeanette completed an MA in Film Production at the University of Bristol, UK, in 2000 and, upon returning to South Africa, realised that the only way to make a film was to get out there and do it. And so, with the support of friends and other grassroots filmmakers, she made Krisimesi, also exploring children’s unique perspectives, which has, in its different versions, screened at various international film festivals and won several awards. She teaches film and has a production company with Matthys Mocke. During my meeting with Jeanette she told me much about her so far only visit to Lithuania. She told me about when she came to Kaunas to try to find the house where her ancestors lived, and how nervous the woman who now lives in the house became when Jeanette knocked on the door, and the fantastic three days that followed when she and the woman, a known Lithuanian artist, afterwards sat down in mutual trust and dialogue… |

PROFESSOR MILTON SHAIN

DIRECTOR OF THE ISAAC AND JESSIE KAPLAN CENTRE FOR JEWISH STUDIES, UNIVERSITY OF CAPE TOWN

|

|

|

Professor Shain excuses himself, mildly and courteously, as he welcomes me in shorts this December day. "It's really all in the middle of summer here," he says as he leads me into the facilities he is the head of, here at the “Isaac and Jessie Kaplan Centre for Jewish Studies at the University of Cape Town”. And it is by his crowded desk that I get to know so much more about the amazing relationships between his ancestral homeland, Lithuania, and the intellectual South Africa he represents. So, dear reader, if you want to know more about Jews in South Africa, you should definitely read Milton's latest book “Jews in South Africa”.

RICHARD FREEDMAN

DIRECTOR OF THE SOUTH AFRICAN HOLOCAUST FOUNDATION, CAPE TOWN

Richard meets me at the entrance to the Holocaust Centre in Cape Town. I was expecting a man that would put the most emphasis on the many tragic events of the Holocaust in Lithuania and in Europe in general. Richard is, after all, a Litvak himself. But what he instead emphasizes, is that there are an infinite number of comparison points between the Holocaust in Europe and the apartheid in South Africa. "Whites who look down on blacks, Nazis who look down on Jews, people who think themselves better than others, aren’t they all of the same kind?", he asks…

KIM FEINBERG

THE ‘JEWISH TEA MOTHER’ AND HER RENTLESS FIGHTS AGAINST HIV-AIDS IN SOUTH AFRICA

The Christmas trees are beautifully decorated in the district of Rosebank, Johannesburg, this summer afternoon in December. I am slowly strolling around when I suddenly see an energetic white young lady in the middle of a crowd of black youths. It turns out that she is a genuine Litvak, and that she is the head of the organization 'Tomorrow's Trust', which in recent years has become a leading institution in the fight against AIDS-HIV in South Africa.

Kim is the one who some years ago walked out of the movie ‘Schindler’s List’ filled with a sense of purpose. “I just thought, ‘I have to do something. I spoke to my rabbi and then started my own oral history project,” she explains.

What an amazing person and determination. Her name is Kim Feinberg, soon 50 years old, still young forever.

RUTH RABINOVWITZ

THE LITVAK MEDICAL DOCTOR WHO REPRESENTS THE ZULUS IN THE SOUTH AFRICAN PARLIAMENT

An unlikely Zulu, Ruth Rabinowitz represents the Zulu Inkatha Freedom Party in the South African parliament!

I meet Ruth in the library of the Johannesburg Grace Hotel to talk about her unusual life and political career. And Ruth tells an almost incredible story. About how her Litvak family, many years ago, became close friends with the Zulu king and his family. She tells about her medical background, but first of all, she focuses on the circumstances for Africa's largest tribe, the Zulus, that today includes three million people, almost as many as the number of inhabitants in Lithuania, the country her ancestors came from (if to count only the present, local population of Lithuania, of course)…

THE HONORARY CONSULS OF LITHUANIA TO SOUTH AFRICA

THREE SUCCESSFUL ATTORNEYS - ALL LITVAKS

|

|

|

|

|

RAYMOND JOFFE Honorary Consul of Lithuania, Johannesburg |

ALAN B. SCHMIEDT Honorary Consul of Lithuania, Cape Town

|

IVOR FEINBERG Honorary Consul of Lithuania, Pretoria |

Here they are. Lithuania's three musketeers in South Africa: Raymond, Alan and Ivor. Three skilled lawyers, all of them genuine Lithuanian Jews. It is these three who make up the front line in terms of current relations between Lithuania and South Africa. It is these three who help facilitate Lithuanians arriving to Africa's southern areas, and they are also the ones constantly informing South Africans about the wonderful country called Lithuania.

They were, some years ago, recommended as consuls by the Lithuanian ambassadors to Israel. Israel? Yes, believe it or not, but the fact is that Lithuania does not have its own ambassador to the country having the largest pocket of Litvaks in the world… The Lithuanian ambassador in Tel Aviv must serve Israel, Cyprus and South Africa altogether. But then, in turn, the ambassadors we've had so far have done a good job. It was, as an exemplary example, the very capable Lithuanian ambassadors Romas Misiunas and Alfonsas Eidintas who recommended these three smart guys we today are naming Lithuania's three musketeers in South Africa.

I have had the pleasure of meeting all three of them several times, both here in Lithuania and in South Africa, and I know that they all burn for stronger ties between our two countries. But I've also heard them talk about how sad it was to experience the Lithuanian Constitutional Court rule that Lithuanian citizens around the globe could no longer be registered as Dual Citizens. They feel, as I do, that it is terribly sad to see nowadays Lithuania burn bridges instead of seeking renewed contact with its fantastic diasporas around the world. In this aspect, sadly, every day that passes is a day lost…

|

|

Rietavas and the

Kaplan family

|

The impressions from the Jewish Museum in Cape Town were as glued to my memory. So in August last year I decided to visit Rietavas, the village the Kaplan family emigrated from almost 100 years ago. I had expected to find proud traces of the family; a museum, a memorial, or maybe even something more sophisticated… But I got terribly disappointed. What struck me, then and there, was that this was almost like coming to Salzburg without seeing Mozart mentioned at all...

What a shame. I took some pictures and went from there with bowed head. Mendel Kaplan, by far the wealthiest and certainly one of the wisest Lithuanians ever, was not mentioned with a single word or symbol in the very home village of his own family...

When I came back to Vilnius from Rietavas that August evening, I sent my photos and comments to Dr. Kaplan in Cape Town. This is what he replied a few days later:

|

Dear Mr Myhre, I thank you for your correspondence on Riteve and your complimentary remarks about our family. When President Landsbergis was surrounded by tanks and holed up in parliament I visited him with my wife and friends in the building and established a very warm relationship. I hope he is still well and I remember the fact that his wife was responsible for saving a number of Jews during the Second World War. Yours sincerely Mendel Kaplan

|

Mendel Kaplan (1936-2009) died of a stroke three months after he sent me the above message. In the obituaries that followed, leading Jews stated that Dr. Kaplan was a man who could be termed “the father of the South African Jewish community.” They wrote that he had served as a leadership capacity in several Jewish organisations, that he was involved in the establishment of the South African Jewish Museum in Cape Town and was also one of the first founders of the ‘City of David Archaeological Excavation Project’ in Israel.

Born in Cape Town, Dr. Kaplan had qualified both in law and with an MBA, survived by his wife, four children and grandchildren.

I never met Mendel Kaplan face to face, but I was told that there had been much for him to celebrate in his 73 years of living: The steel company Cape Gate had been transformed from a modest business selling products like wrought iron and garden benches into a vast conglomerate producing its own steel; becoming one of the largest privately owned companies in South Africa, an expansion largely orchestrated by Mendel and his brother Robert.

Dr. Mendel Kaplan, a world leading Litvak philanthropist, lawyer, writer and business magnate passed away just four months ago. His ties to and care for Lithuania were strong and impressive. Isn’t it time for Lithuania to offer a proper response?

|

|

|

|

Rietavas at the time Mendel Kaplan's parents lived here (around 1900).

|

Old wooden buildings in today’s Rietavas (August 2009). |

|

Lithuanians settling in

South Africa

after1990 |

|

If to compare with the more than 70,000 Litvaks living in South Africa, the numbers of Lithuanian expatriates of today are very modest. But there are a few of them, and I want to tell you all a little bit about Jadvyga Kazlauskiene from the village Vievis between Vilnius and Kaunas. Jadvyga emigrated to South Africa mid 1990s with her daughter, now 20 years old. She started her career down under as a waitress in a Johannesburg restaurant, but began gradually to climb up the career ladder after she came in contact with the property industry in South Africa's main city and most densely populated area.

My personal impression is that Jadvyga's success started the day she met her current manager and boss, property queen Wendy Machanik (along-standing with Jadvyga in the above photo). Wendy is an amazing Litvak with phenomenal successes within real estate brokerage in the Johannesburg area for many years (hi Wendy, are the pictures still hanging there, in correct positions?).

Last time I saw Jadvyga and her family was at her home village Vievis, here in Lithuania, on a very cold winter day just a few weeks ago, when they all came here to bring their beloved mother to her final rest. The contrast between warm Johannesburg and freezing Lithuania must have been enormous. When the funeral was over, I thought that now one more link between Lithuania and South Africa had been cut. How often will Jadvyga come back up north now when her mother is gone?

But maybe there is something we can do to keep the ties and connections alive, all of us who love both Lithuania and South Africa? Please feel free to write me with your suggestions and ideas…

Aage Myhre

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - (1) Comment

Hi, I'm Kristina. I'll try to take you on a small journey. I will provide you with some links to music, poetry, films and more – expressions of art that I personally like and appreciate. Maybe not always so ‘off the beaten path’, but certainly a few times. I will sometimes also express my own thoughts and reflections. But this is also a club and a forum where you as reader and listener can present your own proposals and response. Write to me at kristina.sirvinskaite@VilNews.com These are my today’s suggestions for you:

Music

Poetry

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

Our news section will cover political events

- Posted by - (0) Comment

Lithuanian President Dalia Grybauskaite evaluated the year 2010 as financially and morally difficult, however, according to the head of the state, the most difficult period is almost over.

"The year 2010 was a difficult year for Lithuania, as for many European countries. I think we managed relatively painful, but well. Lithuania withstood the financial crisis, we managed to pay pensions, salaries, people were ensured they will have food and receive salaries. It was a financially and morally difficult year," Dalia Grybauskaite said.

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

We will give economy its fair coverage share

- Posted by - (0) Comment

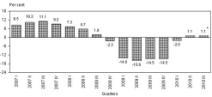

The Lithuanian economy expanded at a faster rate in the third quarter than previously estimated as construction output grew for the first time in almost two years, revised data showed.

The Lithuanian economy expanded at a faster rate in the third quarter than previously estimated as construction output grew for the first time in almost two years, revised data showed.

Gross domestic product grew 1.1 percent, compared with a preliminary estimate of 0.6 percent released on Oct. 28, the Vilnius-based statistics office said in an e-mail. The growth rate was unchanged from the previous quarter.

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

We will cover the energy sector

- Posted by - (0) Comment

Lithuanian President Dalia Grybauskaite praises the government’s efforts in reforming the energy sector but due to unfavourable international situation she iscalling for a pause in attempts of building a new nuclear power plant in Lithuania.

Lithuanian President Dalia Grybauskaite praises the government’s efforts in reforming the energy sector but due to unfavourable international situation she iscalling for a pause in attempts of building a new nuclear power plant in Lithuania.

‘I don’t mean in any way that nuclear energy should be put aside, but perhaps now we’ll have to make a certain pause, rethink and wait for a more favourable international situation without sitting and waiting.

“The fact that we practically haven’t received real proposals and the last investor refused to implement the project only shows the current international situation isn’t favourable,” the president continued. The President believes that the nuclear power should have alternatives and that Lithuania should do more in developing alternative energy.

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

Where are the new ideas for Lithuania?

- Posted by - (0) Comment

Where are the new ideas that could bring Lithuania forwards?

|

||||||||||

|

OLD AND NEW LITHUANIA Photo: Aage Myhre

|

||||||||||

|

Lithuania is a country built on ideas. In my opinion, creativity is this nation’s most fundamental natural resource. Through 800 years Lithuania has time after time been able to show the world that there is an underlying creativity and human power here that enables us to rise again after even the most dramatic defeat or tragedy, again and again to take initiatives that lead to glory, fame and new opportunities for Lithuanians and individuals from other nations and cultures living here. Lithuania needs today new ideas, and I want to challenge all of you who read VilNews to make your suggestions. I consider 2010 an excellent year to initiate a wave of creativity among all of us who want to contribute to this country's best interests. I have in my life invented only one new word. But in return this word was included in the Norwegian dictionaries and encyclopaedias already in the 1980s. The Norwegian Language Council even stated at the time that this was one of the best new Norwegian words they had seen in years, so it would be an understatement not to admit that I was a bit proud hearing this. The word was 'idédugnad', composed of the elements idea and dugnad. Dugnad is a well-known Norwegian word which in translation means something like 'voluntary communal work'. The American term ‘brainstorming’ is very similar, but ‘idédugnad’ somehow represents, at least for me, a more active and pragmatic following up of the ideas, into real action, after they have been put on the table. The reason for my 'invention' was that I 26 years ago initiated a rather huge session with top people from politics, business, culture, education, research, etc. in the Norwegian city of Trondheim, where I studied and lived for the years 1974-1985. As result, a large group of busy individuals met for an entire early spring Saturday to discuss and make proposals on how Trondheim best should be developed towards the city's 1000-year anniversary in 1997. It was a successful session that was later repeated and further developed, and what I think we all saw and experienced was that people from many different professions and cultures quite easily were able to sit together and agree on common objectives. ‘Team Trondheim’ became a real force that included a very broad cross section of people, and the results were quite impressive, as I see it - even today. My hope and desire is that we can get started with something similar here in Lithuania. I am convinced it is possible to also do this here which I think the following listing of some 14 top Lithuanian ideas represents excellent proof of, and I hope we all would be ready to join forces. Lithuania needs new ideas, of course followed by realistic implementation and the power to realise the best ones. I would also suggest for you to have a look at the web page http://www.ted.com/pages/view/id/5 The page represents an American organisation called TED (Technology, Entertainment, Design), with a very simple mission: SPREADING IDEAS. TED also explains: “We believe passionately in the power of ideas to change attitudes, lives and ultimately, the world. So we're building here a clearinghouse that offers free knowledge and inspiration from the world's most inspired thinkers, and also a community of curious souls to engage with ideas and each other.” And, if you can, please spend a few minutes on this one; “William Kamkwamba on building a windmill”. It’s an amazing story about the young boy who one day got the idea to start supplying electricity to his family… http://www.ted.com/talks/william_kamkwamba_on_building_a_windmill.html PS: He succeeded! So, if you don’t mind, send us YOUR ideas for Lithuania that we can share with the other VilNews readers. I also believe passionately; in the power of ideas to change attitudes, lives and ultimately, Lithuania.

Aage Myhre, Editor

|

||||||||||

|

Are these the top 14 Lithuanian ideas throughout history?

|

||||||||||

|

|

1200s King Mindaugas’ grand idea was to found the Lithuanian State! Lithuania’s only king is also credited with stopping the advance of the Tatars towards the Baltic Sea and Europe, establishing international recognition of Lithuania, and turning it towards Western civilization. |

|

||||||||

|

|

1300s Gediminas’ idea was to found Vilnius as one of the World’s most tolerant cities Grand Duke Gediminas was also the true founder of ‘The Grand Duchy of Lithuania’. He was a man of extraordinary knowledge and wisdom, offering free access into Lithuania to Europeans of every order and profession. |

|

||||||||

|

|

1400s Vytautas the Great’s idea was to expand ‘The Grand Duchy of Lithuania’ Vytautas the Great was the Grand Duke expanding the Grand Duchy‘s frontiers from the Baltic Sea south to the Black Sea and thereby creating the by then largest country in Europe. The Grand Duchy was at its largest by the middle of the 15th Century. |

|

||||||||

|

|

1500s Sigismund the Old’s idea was to connect Italy and Lithuania, with the help of Leonardo da Vinci!

When Lithuania’s Grand Duke, Sigismund the Old in 1518 married the Italian Princess Bona Sforza, this became an outstanding manifestation of the already strong relationship between Italy and Lithuania. The royal couple created together an Italian community within the court and Italian culture became the preoccupation of the Vilnius city elite.

|

|

||||||||

|

|

1700s The Gaon’s idea was to make Vilnius the intellectual cradle for world Jews The Great Gaon of Vilnius, Elijahu ben Solomon Zalman (1720-1797) was the greatest luminary not only among the many Talmudical scholars of the 17th and 18th centuries, but also for many later generations.

|

|

||||||||

|

|

1875-1911 Čiurlionis’ idea was to describe Lithuania’s soul in his art and music During his short life Lithuania’s national composer and painter, Mikalojus Konstantinas Čiurlionis, composed about 250 pieces of music and created about 300 paintings. His works have had a profound influence on modern Lithuanian culture.

|

|

||||||||

|

|

1918 Antanas Basanavičius’ grand idea was to reclaim independence for Lithuania

As a member of the Council of Lithuania he was a signer of the Act of Independence of Lithuania on the 16th of February 1918 (signed in the building at the picture to the left). Basanavičius is often given the unique informal honorific title of the "Patriarch of the Nation". |

|

||||||||

|

|

1918-1940 President Smetona had the idea of again making Lithuania a successful, remarkable nation

President Antanas Smetona was undoubtedly Lithuania’s most important political figure between the two wars. He served as President from 1919 to 1920, and again from 1926 to 1940. Smetona was also one of the famous ideologists of nationalists in Lithuania. The country was truly flourishing under his presidency.

|

|

||||||||

|

1940-1945 |

||||||||||

|

|

1945-1990 Lithuanians who were forced to leave their home country had the idea of keeping on fighting

The post World War II wave of Lithuanian immigrants experienced a surge of Lithuanian consciousness. They saw themselves as exiled communities and clung to their memory of two decades of freedom in Lithuania. They also made numerous efforts to support Lithuania’s freedom fight.

|

|

||||||||

|

|

1945-1990 Lithuania had the idea to improve its infrastructure even during Soviet years Despite huge post war difficulties, Lithuania managed to build around 450 km of four-lane motorways from Vilnius to Klaipėda and Panevėžys. Result? Lithuania got the best roads in East Europe! At the same time Klaipėda port was developed as a leading Baltic transport hub, connecting East and West..

|

|

||||||||

|

|

1960-1990 Despite the oppression, Lithuanian experts had the idea to make Lithuania the Soviet Silicon Valley Still today Lithuania is the world‘s leading exporter of femtosecond lasers. Among the clients is NASA, using Lithuanian laser technology for analyses of minerals on Mars! A country of 3.5 million people, Lithuania, has about 15 laser producers, employing about 300 laser specialists!

|

|

||||||||

|

|

1988 – 1991 Landsbergis had the idea that his masses of unarmed Lithuanians could win over the mighty Soviet army Hadn‘t it been for this peaceful fight by Professor Vytautas Landsbergis and his people for regained freedom against an occupation and a ruling the people of the Baltic States never wanted or agreed to, the map of Europe would most likely have looked very different today...

|

|

||||||||

|

|

1990 – 2010 Lithuania’s sport and culture had the idea to remain on world level I let two of the most prominent figures within these fields represent the fantastic flora of ideas and pure guts sport and culture is playing for Lithuania; Music Professor Donatas Katkus (left) and former basketball player Arvydas Sabonis. Remarkable!!

|

|

||||||||

|

|

2000 – 2010 Zuokas’ idea was to build Lithuania’s Manhattan Vilnius’ former Mayor, Arturas Zuokas, earned his place in Lithuania’s history with his energetic efforts to build a new skyscraper city within the city.

|

|

||||||||

|

|

|

2010 - ? Ms. President & Mr. Prime Minister,

Please let us know what are your ideas and visions for the future development of Lithuania. |

|

|||||||

|

|

||||||||||

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

We will follow Lithuania in the world

- Posted by - (0) Comment

During a visit to Washing last autumn, Lithuanian Prime Minister Andrius Kubilius explained that there were some doubts about the US intentions toward the Baltic States after the United States signed the treaty with Russia on reduction of the nuclear arsenal in spring. However, those doubts were cleared by the US administration itself, Lithuania’s Prime Minister said during his interview to the public radio on 7 September.

During a visit to Washing last autumn, Lithuanian Prime Minister Andrius Kubilius explained that there were some doubts about the US intentions toward the Baltic States after the United States signed the treaty with Russia on reduction of the nuclear arsenal in spring. However, those doubts were cleared by the US administration itself, Lithuania’s Prime Minister said during his interview to the public radio on 7 September.

‘When the US president and the Russian president signed the so-called nuclear munitions restriction treaty, there were some doubts over what Russia would get for it in return. The doubts were in connection to drafting of treaties on conventional forces but they were dispelled in a very efficient and proper manner by the US administration and its representatives,’ Kubilius said in the interview. The Prime Minster once again repeated that the US has been and will remain ‘among Lithuania’s most important strategic partners.’

Lithuanian President Dalia Grybauskaite that the main reason behind snubbing Obama’s invitation to join the dinner in Prague because, ‘Seeing that this (the US and Russia treaty) could conflict with the interests of at least Eastern Europe and the Baltic region, I did not want to drink champagne to this perspective.’

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

Lithuania in a world perspective

- Posted by - (0) Comment

A reader who responded to one of our VilNews issues last year argued that our publication had begun to go in the footsteps of local Lithuanian media in describing Lithuania in a rather negative way. I can well understand such a reaction, but it must also be said that unfortunately there has been a relatively large number of cases and circumstances in this country that deserve to be described in quite critical terms.

The bad

• The Lithuanian people, especially the weakest groups, are very hard hit by the economic crisis that continues to affect much of the world. The country's pensioners and other disadvantaged groups continue to live under very miserable conditions, and one must be allowed to make critical remarks on how this country's authorities have acted in the handling of the crisis. It seems to me that Lithuania's government has been more concerned with finding their own solutions, trying to ‘reinvent the wheel' rather than to learn from what other nations have made with regard to stimulus packages, lowered interest rates, etc. in these times of crisis, which in my view unnecessarily sets Lithuania several years back in time compared to many other countries. Fortunately, it appears that the immediate panic that came to characterize both the government and the banks in 2008-2010, seems to be slowly taken over by more mature attitudes now in 2011.

• There has still been far too little done for increased foreign investments in Lithuania, even if there were some good efforts made during 2010. Also the country's own industry has largely had to fend for themselves without the kind of facilitation and support one sees taking place in countries frequently compared with Lithuania.

• The country has been constantly ill-placed on Transparency International's statistics on corruption and transparency over many years, compared with other European countries, a situation which clearly has hindered economic growth and a better society for its own citizens. That corruption and bribery is still a part of the country's 'culture' in business and public institutions is nothing less than a big shame!

• The country's press must, unfortunately, largely be described as underdeveloped, with too much emphasis on celebrity and scandal reviews, and too little emphasis on constructive and investigative journalism that focuses on corruption and other undesirable conditions that continue to hold this country down. But many would also say that the media focus too much on the negative, too little on all the positive things going on here.

• A huge proportion of Lithuania's population has emigrated in recent years, including many of those with higher education, and one can rightly ask what is done to create new jobs and make necessary provisions to keep these groups remain in their home country.

• One of Lithuania's most prominent human resources is undoubtedly the country's large diasporas around the globe, groups of people and their descendants who left their mother country because of war, difficult economic conditions, political persecution, etc. These diaspora groups are in my view too little listened to or consulted from the Lithuanian authorities, which is very sad for a nation that so desperately needs all possible support and assistance from the hundreds of thousands who still have Lithuania in their hearts.

• When Lithuania's Constitutional Court in November 2006 ruled that the country's Law on Citizenship should be interpreted in disfavour of dual citizenship for large groups of Lithuanians and their descendants having citizenships in other countries, this became the start of a still heated debate around the world, as many within the country's numerous diaspora groups felt that their country of origin did not want them back or did not want to appreciate them as full Lithuanians. Many felt that the Court's decision in its interpretation of the law was more influenced by hidden motives and intentions rather than common sense. As previously stated, Lithuania desperately needs goodwill from all of its huge diasporas, and should be more eager than most other countries to allow dual citizenship. Lithuania’s welcome-back-door must be kept constantly open, never closed. We need everyone who is ready to contribute and make an effort for the mother country.

• The Lithuanian school system, especially at higher levels, is still dominated by Soviet-era thinking and there is good reason to ask what has been done the last 20 years to make it more conducive to more advanced and modern education, research and collaboration between education, businesses and government.

• Health Service has major and serious deficiencies, and also suffers under the fact that many of the nation's doctors and nurses have emigrated to Western countries.

• The focus on travel and tourism has largely been unsuccessful, partly because of the disproportionately high airport taxes (the good news is that this was finally understood and these taxes were drastically lowered in 2010), under-developed ports for ferries and other ships in the Baltic Sea city of Klaipeda, poorly developed infrastructure and promotional activities, as well as little support to hotels and other tourist industries.

• Vilnius as European Capital of Culture in 2009, must also be described as a flop due to the fact that the number of visitors to the city was sharply down instead of up as expected, not least because of the unstructured and poor planning, and as several flights were cancelled due to FlyLAL's bankruptcy, too high airport charges and poor decisions by authorities. The planned main symbol of the year of culture, the re-created royal palace at the cathedral in Vilnius that should have been completed in all its glory during the culture year, still stands there as a ghostlike skeleton surrounded by construction cranes.

• The statistics for suicide and violent crime in Lithuania is sad reading, and the country is among those on the very bottom of all these statistics compared to the rest of Europe.

• Lithuanians make up for a disproportionate share of criminal gangs in Western Europe and the United States, something which increasingly creates major problems for the police and the judiciary in many countries and also leads to frequent negative headlines about Lithuania in the Western media.

• Lithuania is still suffering under a lot of pending historic "dirt", for example with regard to its dealings with the Holocaust and the fact that relatively many Lithuanians collaborated with the Nazis in the extermination of the Jews here. There was also an extensive collaboration between the KGB and senior Lithuanian politicians through the Soviet time, and it is still missing a wide clarification of what actually took place in the post-war partisan war. Reconciliation must be the obvious target, but based on all the facts laid on the table in a most scientific, objective way so that whatever might have been of injustice or illegal actions come to light and can be reacted to. A firm and fair treatment of these historical conditions will provide Lithuania great honour both domestically and from the international community.

• Participation in voluntary organizations is record low in Lithuania compared to other EU countries, and it seems that people in this country has relatively little liking for and willingness to teamwork and to work jointly with others within their neighbourhoods, local communities or on a national level. Is it perhaps selfishness, greed and mistrust of other people behind this?

The good

But, then, there is so very much positive that can be said about this country that many of us have become so fond of during the years after the liberation from the Soviet Union in 1990/91.

Lithuania has in many areas undergone an admirable growth for several years until the economical crisis started, which I recently saw very nicely symbolized by the many great new buildings that have shot up in the outskirts of Vilnius since I first came the same road into town in November 1990 on tour from my native Norway. Vilnius was by then a city that I experienced as sad, dark and worn, but is now a modern metropolis on a European level. An important part of this picture is the incredibly beautiful Old Town in Vilnius, which has now been renovated and re-emerged as one of Europe's finest and most attractive tourist magnets.

Also, coastal areas have undergone phenomenal change for the better. A summer stroll through the newly renovated Palanga city or at Europe's largest sand dunes in Nida are good experiences fully on par with what one finds in other countries' tourism destinations. The spa-town Druskininkai in South Lithuania has similarly undergone great improvements, and stands today as one of Europe's most attractive for anyone who wants to 'recharge the batteries' and at the same time enjoy the truly wonderful sceneries of Lithuania’s forest and lake landscapes.

It pleases me very much every time I visit my in-laws lush garden outside Vilnius. The practice of garden-towns is still alive and well here, and represents, in my opinion some of the closest you can get to this country's soul. Worth a visit!

Let me also mention the fantastic cultural life that so much characterizes this country. Music festivals that mark the cities and towns every summer. Most professional theatre, ballet and singing performances that fill the country's many stages throughout the winter months. Art exhibitions of all kinds, and spontaneous performances of various theatre and music groups in courtyards, squares, settlements and villages across the country. One needs never get bored in Lithuania!

And, let me share with you what two late statistics say about Lithuania:

According to the “2010 Quality of Life Index” published by the “International Living” magazine http://www1.internationalliving.com/qofl2010/, Lithuania is among the 25 best countries in the world to live in, with better quality of life than most other countries of Central and Eastern Europe (even ahead of some West-European countries).

Vilnius can boast of the cleanest air in Europe according to the „Economist Intelligence Unit“ and „Siemens“ in a research study called “An Index of Green European Cities” in which 30 cities-capitals of Europe were participating. http://www.vilnius-tourism.lt/topic.php?tid=84&aid=2304

Conclusion

It is my hope that Lithuania's authorities, businesses and people in general seriously start to cope with the still remaining problems and negative conditions, so that we can put behind us the negative features and once again see and experience a Lithuania with similar positive guts, profile and multi-cultural constellations that this country was once so famous for.

The initial question was what we can do to improve Lithuania's reputation to the rest of our world.

Many would probably say that what we need is more positive attention in international media. And, in fact, over the years there have been spent large sums on advertising Lithuania and Vilnius on CNN and in other media. It has been printed countless brochures, and it has repeatedly been created commissions that should propose new logos, new slogans, new profiles and new ideas for international promotion of Lithuania. But I hardly exaggerate when I say that the usefulness of all this has been extremely limited.

My answer to the question would therefore rather be to open up for a broad process with the aim to overcome, and actively improve the problem areas I have outlined in my bullet points above. I believe this would be a far better starting point and professional platform for improving Lithuania's reputation. Such a process would in itself attract attention and recognition in international media, as well as among leaders and ordinary people around the world.

Nothing gives better reputation for a nation than when the country’s authorities and citizens join forces into a positive and determined development process based on openness, fairness, honesty, genuine concern for fellow human beings, true respect for law and order, hard work, and attempted professionalism on all levels.

Lithuania has the historical and contemporary power to again become a leading, prominent example nation for other developing countries and many others around the world. Let’s take the opportunity.

PS:

I am fully aware that I have embarked into a minefield by writing the above comments, but after living in Lithuania more or less continuously for 20 years now, I feel that I have some background to indicate an ever-so-small number of perceptions. Giving advice to others, however, is always a risk sport. To be a bit critical is even more risky. I have no roots in or from Lithuania, but I have my 'branches' here, and I would so dearly like my descendants and all other Lithuanians again to feel pride when they tell of their Lithuanian background. Therefore, I have written this, and I hope it will be well received as a constructive contribution with the best intentions and wishes for a brightest possible future in and for Lithuania.

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

Thank God I found Lithuania!

- Posted by - (0) Comment

A personal thank you note to Lithuania from David Telky, Scotland

David Telky, Managing Director of Scottish-Lithuanian manufacturing company Pentland, has over 35 years in the Clothing Manufacturing industry. David was born in Glasgow, Scotland where he has carried on the family business of 90 years to present.

Pentland is a Scottish based clothing manufacturing company headquartered in Glasgow with its production sites in Lithuania, Belarus and Moldova. Pentland has been manufacturing tailored clothing in Glasgow since 1973 and moved its production to Eastern Europe in 1985. Pentland produces for the European market for leading fashion retailers delivering tailored outerwear for men and women, with over 40 factories in Lithuania and neighbouring countries.

Thank you Lithuania!

Text: David Telky

The above quote took over 30 years to occur. It covers activities in 14 countries and many years of garment production around the globe.

My background was in accountancy, but when my father, a tailor, phoned me to return to Scotland to help him start a large factory, I needed no second request.

Accountancy could not stand up to the thought of working with my father, starting a new factory and working in a manufacturing environment that had been a family trade for generations.

Two years later, after my training was over, the factory we designed was completed and my theory was to be put into practice.

To finance the project, at a very stormy time in the British economy , took every penny that we could beg and borrow but the beautiful factory was ours (and the banks)and now we had to staff and provide orders for it's production.

10 eventful years later, sadly after my wonderful Father died, the factory had expanded to 450 people and was making 10,000 jackets a week, but customers were moving to overseas production, mainly from China!

This was when the stresses of running a large enterprise in Glasgow bore the health problems that many find the hardest part of business management. The long hours the mental strain of multiple problems, the financial pressures, the staff aggravations.

The answer was to do what all similar enterprises in UK were looking at and out source production, but where?

Over the next 5years,after successful forays into China, Indonesia, Sri Lanka, Turkey, Poland ,Portugal, Belarus Egypt and a few not so successful, I found the right place, Lithuania- my search was over!

The stress of all this had seen me in hospital with health problems, that linger to this day, so the expression "thank God for Lithuania ...without it I could be dead!" evolves from the joy of working with some of the best staff I have ever employed, combined with some of the finest and most loyal factories producing excellent products with an almost old fashioned loyalty and ethic that was so prevalent in the UK of my youth.

Altogether the move to Lithuania has not only been a work influenced move but the social aspect of the community of local and expats has opened my eyes to a life of harmony and peace that I thought was lost forever and fills me each day with happiness.

So Thank God for Lithuania in it's helping me develop not only a great company Pentland , a sum of it's fine employees ,but for giving me the chance to meet so many great and wonderful people not least the Editor of this fine Journal, Aage Myhre ,who I am honoured to count as my good friend .

May I say that the journal that Aage has developed tirelessly over many years is a fine demonstration of his love of Lithuania that I am proud to share with him!

Good luck to Vilnews and to you my friend Aage Myhre!

David Telky, Managing Director of Pentland – Scotland and Lithuania has over 35 years in the Clothing Manufacturing industry. David was born in Glasgow, Scotland where he has carried on the family business of 90 years to present. David participates hands on in his manufacturing companies from sales, production to delivery – producing fashion garments for the British and other western markets.

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

Some awful Lithuanian statistics

- Posted by - (1) Comment

Text: Diana Koval

According to some publications, Lithuania has been named the EU murder capital. According to the Eurostat agency Lithuania saw an average 8.76 murders per 100,000 heads of population every year during the period 2002-8. However, this information, which showed up in various world media publications seem to be not completely up to date.

Death rate in Lithuania is among the highest in Europe. The only “good” news is that Lithuania finally stopped being the “murder capital”. According to Eurostat, in 2009 deaths due to homicide and assaults got the highest rate in Latvia (5.9 person of 100.000), while Lithuania stays behind on the 2nd place with death rate 5.6 person. Unfortunately, due to other causes such as suicide (31.5 of 100.000 comparing to Greece’s 3.0), ischemic heart diseases (305.1 comparing to Netherlands’ 42.8) and various accidents (68.2 comparing to Germany’s 14.6) Lithuania has the highest death rates in EU.

Statistics Department of Lithuania recently claimed that every day approximately 100 people are being born and 115 are dying (among them 1-due to transport accidents, 3 – committed suicide)

Lithuania still has the highest rate of death due to suicide in Europe, which was 31.5 of 100.000 inhabitants and then goes Hungary (21.8) and Latvia (20.7). Majority of them are being committed in urban area - Vilnius and Kaunas counties. People are killing themselves from various psychological reasons, desperation, bullying at school, depression, unemployment, and finance debts.

One of the biggest problems that Lithuania faces today is violence against women. Statistics claims that 63% of all women in Lithuania suffered from physical and/or psychological violence, whereas world average is 33%. According to Police department in 2009 there were approx. 42.000 police calls due to family conflicts and more than 8.000 of them were women who suffered from their husbands, partners or even from their children domestic disputes. Yet statistics are just the tip of the iceberg so one may wonder what the true numbers of such incidents are. The majority of people are more likely to think that domestic violence is a private family matter. Although there are laws prohibiting family violence, sometimes they aren’t as effective as they should be.

Another topic that needs consideration is incredibly high unemployment rates. According to Eurostat in November, 2010 unemployment rate in EU was 9.6% while Lithuania’s was 18.3%. Higher rates were registered only in Spain (20.6%), while in Netherlands unemployment rates were just 4.4 %. By January 2011, about 311.300 job seekers were registered by the Lithuanian Labour Exchange which is 14.4% of people of working age. Mindaugas Petras Balašaitis (Head of Lithuanian Labour Exchange) considers the situation at the state job market as very unusual: the unemployment growth slows down but somehow there is lack of qualified employees on Lithuanian job market (due to emigration, which is another deep problem for a country).

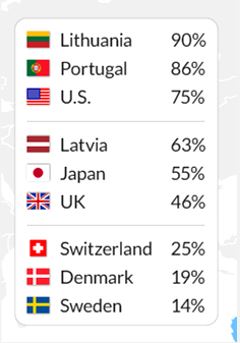

Furthermore, voluntarism rates in Lithuania are also incredibly low. Only 2% of population volunteered for some organizations comparing to Sweden’s 90%.

However, the situation in other Baltic states (especially Latvia) is also difficult. After the proclamation of Independence in 1991 Lithuanian society confronted sudden changes which were difficult to deal with. Psychologists claim that uncertainty and insecurity, worsening economic situation as well as rapid changes are the main reasons of this complicated status in Lithuania. Still it is merely (and mainly) a question of time when things will start improving.

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - (1) Comment

Venclova`s Vilnius

This article is from the book “VILNIUS a Personal History” written by Tomas Venclova.

From reading Mr. Venclova’s Bio you can understand why we are excited and honoured to have him as one of the contributing writers for VilNews. In the future we will continue to post excerpts from his book for your reading enjoyment. We thank the publisher, The Sheep Meadow Press for their gracious consent in allowing us to share Mr. Venclova’s book with you and we would like to direct you to The University Press of New England who is the book’s distributor.

Published at:

Sheep Meadow Press

http://sheepmeadowpress.com/

Distributed by:

University Press of New England

http://www.upne.com/index_new.html

Text: Tomas Venclova

Vilnius was founded by Lithuanians, and in the Middle Ages they presumably established the tone of the city. Later, this changed radically. In Bakhtin’s* day, only about two percent of the citizens of Vilnius spoke Lithuanian. After the Second World War, everything changed fundamentally. As the tanks of several occupying armies rolled through the city, half of its inhabitants were murdered, the other half driven out or deported. Lithuanians from villages and small towns, intellectuals (my parents among them) who had earlier been drawn to Kaunas, the second largest Lithuanian city, streamed into the de-populated Vilnius. In short, thousands of people were getting to know their nation’s legendary capital for the first time and had difficulty gaining a foothold in their new surroundings which, quite apart from everything else, were being subjected to the hand of Communist power. Only now, several generations later, do Lithuanians constitute a majority in Vilnius and feel at home there. Today, the Lithuanian language predominates in the streets and has supplanted other languages on signs and public notices. (Despite the protests of philologists, these signs are often printed in English.)

In the surrounding villages, Lithuanian is certainly not spoken everywhere. You have to drive at least thirty miles north or south to hear the old language again. Its dialects differ greatly from one another: for example, the Aukstaiciai, who live in the northern coastal region, have long been known for their sensitivity and imagination; the Dzukai, from the southern pine forests, have always struggled with their sandy soil and sell their berries and mushrooms in Vilnius. The villages of these two groups extend all the way to Belarus―and Belarusian settlements extend into present-day Lithuania. From an ethnic standpoint, the border east of Vilnius follows a completely arbitrary course―even though it separates the European Union from a country still under dictatorial rule. Lithuanians and Slavs have always lived together in the areas surrounding the city. One can probably say that Vilnius has always been on the European border―a sort of transit lounge.

The second historic people of Vilnius called themselves Ruthenians. In the Middle Ages, their language was probably heard as often on the wooden sidewalks of the city as Lithuanian. The Ruthenians were already building their Orthodox churches when the Lithuanians were still heathens. In governmental affairs, the Slavic language predominated because writing was connected with Orthodoxy. It is hard to say just when the East Slavic tribe of the Ruthenians became a separate people. At first, the only thing that differentiated them from the Muscovite Russians was their dialect, but later, when they developed a greater affinity with the West, their political orientation followed suit. Ruthenian churches did not belong to the Patriarchy of Moscow but rather to the Patriarchy of Constantinople, which did not always agree with Moscow.

With the passage of centuries marked by turmoil and religious wars, the Belarusian people gradually formed out of the Ruthenians in the Vilnius area and further east. Even today, having settled among Russians and Poles―Orthodox Christians and Catholics, respectively―Belarusians lack a distinctive identity. Moreover, their contact with the Lithuanians also had consequences. There are many Lithuanian words in the Belarusian language, and many Belarusian or Ruthenian words in Lithuanian, especially ecclesiastical words. The grammar of the Belarusian language was only codified by twentieth-century nationalists; the nationalist movement they triggered was the latest to occur in all of Europe. The Belarusians―like their neighbors the Dzukai―held on to their archaic mythology, folklore, and customs; they were long known not only for their generosity but also for their poverty and their inability to subsist on the barren soil of a region where there were practically no roads. Up until the First World War, four-fifths of the population were illiterate. Politics determined how they were classified in passports and statistics. Whatever nation happened to be in power at the time would count the Belarusians among its own people, even if it looked down on them. Today, some Belarusians describe their nationality with the word tutejszy—“local.” Another Ruthenian dialect goes back to the origins of the Ukrainian people, but that is another story. The Ukraine is far to the south of my country.

The third historic people, the Poles, had the greatest impact on Vilnius and its surroundings for several centuries. Catholicism came to Lithuania from Poland and brought with it a different way of life. Relatively few Poles actually came to Vilnius―most of them priests. The local Lithuanian and Ruthenian upper class viewed the Polish aristocracy with great mistrust and tried to keep them from settling in their territory in every imaginable way. But at the very same time this local upper class, captivated by Polish Renaissance customs and freedoms, quickly decided to adopt the Polish language. This is a paradox rarely encountered elsewhere in Europe: the upper strata of society were in all respects Polish, but they stubbornly called themselves Lithuanians―as opposed to the “genuine” Poles from Krakow and Warsaw.

In the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, city people primarily spoke Polish. Lithuanian and Belarusian were relegated to the rural regions and became a sign of peasant origin and backwardness. Actually, Belarusian is not very different from Polish and was considered one of its dialects. The Lithuanians faced a situation similar to that of the Irish: their language had about as much in common with Polish as Gaelic had with English, and therefore many people considered it just a historical curiosity―quaint, but doomed to oblivion. The Lithuanian intelligentsia managed to change this viewpoint (they were more successful than the Irish), but it was difficult and took a long time. In other words, there were two types of Lithuanians: the first type knew only Polish and couldn’t imagine a life without Poland, even though they were local patriots, whose forefathers spoke Lithuanian (or Ruthenian); the second type, who were less conspicuous, still spoke the old Lithuanian language and dreamed of an independent Lithuanian state. This social division resulted in considerable animosity. Later, it turned into armed conflict, which would determine the fate of the city.

Józef Piłsudski, who founded the independent Polish state after the First World War, saw himself as having Lithuanian origins, as did Adam Mickiewicz in the nineteenth century and Tadeusz Kósciuszko in the eighteenth. Piłsudski liked to say, “Poland is like a pretzel―everything that’s good about it is in the outer crusts, and inside there’s nothing.” Among these “outer crusts,” Piłsudski ranked Vilnius above all others. He had been educated in Vilnius, and it was there that he had first become interested in revolutionary ideas and was first arrested for taking part in a conspiracy. Another conspirator in that same plot, Lenin’s older brother Alexander, was hanged. But Piłsudski survived and eventually, weapon in hand, liberated his own country, brought Lenin’s Bolsheviks to a standstill at the Vistula, and marched into the city he had grown up in. For the next twenty years, Vilnius would remain a part of his country, Poland. Although Piłsudski’s heart is buried in a Vilnius cemetery, the Poles are today a minority in the city; they no longer form the upper class, nor even the educated class. For the most part, they are laborers, craftsmen, former peasants. The Polish language is still dominant in the surrounding villages, although it is difficult to establish precisely where it spills into Belarusian.

There are also genuine Russians in Vilnius. The first Russian probably came to Lithuania from Moscow as early as the sixteenth century: Prince Kurbsky, the patron of all Russian dissidents and political émigrés. After a dreadful falling-out with Tsar Ivan “the Terrible,” Kurbsky wrote letters to his former ruler from nearby Lithuania. The Tsar replied with angry, but impeccably literary outbursts. This was the start of a polemic between tyrants and their opponents that has continued in Russia ever since. About a century later, émigrés appeared who disagreed with the reform of the Orthodox Church and had decided to preserve the old liturgy and morality. These so-called “Old Believers” put down roots in Vilnius but continued to speak their own language, which is quite distinct from Belarusian and Polish―and not at all like Lithuanian. The Old Believers gained a reputation as quiet, hardworking people. Their churches are modest and do not resemble Orthodox churches at all. One of them, behind the train station in an out-of-the-way section of Vilnius, is surrounded by high walls that formerly protected it from attacks by followers of the New Orthodox Church who threw stones at the Old Believers.

When the city was under Tsarist occupation in the nineteenth century, these New Orthodox Russians came to Vilnius in great numbers. They built churches, usually in the most conspicuous locations: even today their threatening, onion-shaped cupolas loom high above the city―in sharp contrast to the graceful Baroque of the Catholic churches. During the Soviet era, Russians made up at least one third of the population. The majority had moved to Vilnius only after the end of the Second World War. At the time, all public notices and signs had to be printed in Cyrillic lettering as well as in the Roman alphabet. Lithuanian and Polish schools devoted considerable time to learning Russian. I wasn’t too upset about that because I was just beginning to love Alexander Pushkin, as well as the later Silver Age poets Anna Akhmatova and Osip Mandelstam, who were not listed in the syllabus or mentioned in school at all. But I was an exception; my classmates equated the Russians with the unbearable Soviet government. When it collapsed, the majority of Russian civil servants and military personnel left Lithuania, accompanied by their daughters, who had piqued my youthful interest. But quite a few intellectuals―who were, as a rule, closer to Kurbsky’s tradition than to that of Ivan the Terrible―remained, and this too is still noticeable in the city.