THE VOICE OF INTERNATIONAL LITHUANIA

|

VilNews has its own Google archive! Type a word in the above search box to find any article.

You can also follow us on Facebook. We have two different pages. Click to open and join.

|

Author Archive

- Posted by - (0) Comment

Ars longa, vita brevis

Art is long, Life is short.

Professor of Creative Writing and American Short Story at Concordia University, Canada,

the founder and main organizer of the SLS, and author Mikhail Iossel.

Photo: Kestutis Pleita

Professor Mikhail Iossel interviewed by Eglė Kačkutė

This summer, July 15-28 and August 29-12, the 14th edition of Summer Literary Festivals known as the SLS will be held in Vilnius for the 3rd time running. Literary workshops will be conducted by experienced and well known North American writers; famous photographers, artists and researchers will be taking part in the program. SLS is the biggest independent creative writing program in the world that brings together an impressive number of talented teachers and writers to be. The creative writing phenomenon is rife in Europe, too. The first British Creative Writing course graduate in the UK is legendary Ian McEwan who continues to reap the plentiful fruit of his studies at East Anglia University thirty odd years ago. Creative studies are known to be more that just a means to get better at writing, they also serve as an initiation into complex and competitive world of publishing, providing writers to be with much needed references.

Eglė Kačkutė is talking to professor of Creative Writing and American Short Story at Concordia University, Canada, the founder and main organizer of the SLS, and author Mikhail Iossel.

This year for the fourteenth time running, you’ll be organizing the biggest international creative writing program featuring North American and Canadian writers. You teach creative writing at Concordia University and are a writer yourself. What’s your story? How did you come to writing in English and especially teaching writing in English?

I came to the US in 1986, after five years of having my application for émigré visa turned down by the competent organs. Back in Leningrad, which is where I was born and raised, I was trained and for a few years worked (poorly and lackadaisically) as an electrical engineer, in the employ of the research institute charged with the task of lowering the electromagnetic fields radiated in the ocean by the outmoded Soviet submarines, so as to make the latter less detectable by the enemy radars (it was a hopeless enterprise, of course); and I also – especially since the beginning of the 80s -- was active in the city’s burgeoning underground (“samizdat”) literary community.

(Once I had become a “refusenik,” however, my line of occupation had changed quite drastically, and for the last couple of years of my “Soviet” life I worked as an alternate night-guard at Leningrad’s Central Park of Culture and Leisure, tasked with the responsibility of keeping an eye on the city’s only roller-coaster. I loved that job.)

My original “Plan-A” idea, before arriving in America, had been to make a living in the new world by continuing to write in Russian; and when, within the first day or two of my post-Soviet life, it was explained to me how and why that wouldn’t work, I found myself at a loss as to what to do next, for I had no Plan B. One thing I did know for certain, though: I didn’t want to be an engineer again – and in general, I had resolved for myself never to try and make a living by doing anything that, to me, felt like a waste of life.

I could read English well enough, at that point – back in Leningrad, I had translated some contemporary American prose and poetry for “samizdat” journals, including the one I co-published myself – and my spoken English was rather passable; but my oral comprehension, in the absence of any prior practice, was pretty abysmal, not to mention my ability to write in English, which was non-existent, for all intents and purposes.

In an effort to improve the quality of my English quickly – and because the idea of being surrounded by books was soothing and appealing to me, in my discombobulated state just then – I undertook a string of part-time jobs with some terrific bookstores: first around the Harvard Square and other parts of larger-Boston area – and then in Northern California, where my relatives on my father’s side lived.

Unfortunately, I was unable to keep any of those jobs for long. I was, at that point -- not atypically for many Soviet émigrés in those days (when one left the country, and one’s friends and family, forever, in the firm knowledge he would never be able to go back and see them again) -- in a fairly sorry state of mind and spirit: confused, depressed; in a word, sick. I had no clear personal strategy for survival. It was purely a day-by-day kind of existence.

I watched television for hours on end, cooped up in my tiny, overheated sixth-floor, rooftop room on the outskirts of Boston, in a large rambling walk-up apartment owned by a Russian émigré, where seven or eight other people (mostly, from Columbia, for some reason) lived; but my old, rabbit-ears TV, which I’d found on sitting on the sidewalk one day, only allowed me to watch one channel -- and it was the Boston Celtics, basketball channel. So I was mainly learning the basketball-related part of the language.

At some point during those months, in order to distract myself from the sheer uncertainty and sadness of my circumstances, sleepless and homebound and unemployable, I started trying to write sentences in English. Not stories, at that point, just yet – just the competent, authentic-looking sentences. It was, at first, a purely mechanical, self-therapeutic exercise: putting together the small blocks of short, direct sentences, one after another. It was indeed a comforting exercise for me: I was overwhelmed with nostalgia, you see, and my native language, Russian, would not allow me to write about my life objectively and dispassionately, with any degree of calm remove, for it was as natural to me as the very air I breathed and therefore offered no resistance in the process of writing; and as soon as I started writing in Russian, I immediately succumbed to sadness and depression and commenced to wallow in misery and self-pity. The very foreignness of a foreign language – English – afforded me the distance I needed to put between myself and my own life, my present circumstances and my memories. A foreign language one knows well enough to know he doesn’t know it well serve as a natur4al obstacle every writer needs to come up with for the purposes of his or her writing. I could not wax emotional in English, could not feel sorry for myself, could not write soulfully and beautifully about my nostalgia, about the friends I would never see again. I could do nothing but be adequate to the words I was trying to put on paper. English, then, served as a sort of Plexiglas wall standing between myself and my past, my very life. I only could be adequate, as I said, to any English sentence at hand.

One sentence, then another one, and another and soon enough, you have a paragraph. Then another paragraph, and then another. Every sentence had to make direct narrative sense, and every single paragraph had to work towards the telling of the story under writing. It was like walking a narrow path through the swampland: you don’t want to deviate from it at any point, or else you’ll get bogged down without a trace.

Incidentally, and a propos of what I am describing right now: when Samuel Beckett – perhaps the most linguistically gifted and prodigiously verbose (in his youth) writer in all of the 20th-century literature, was asked why, at the age of 46, he switched to writing in French (a language he was not perfect in)< he replied: “I know too many words in English.”

So it went. By that point – early 1987 – a friend at one of those bookstores I’d worked at had told me about the phenomenon of graduate creative writing programs in the US: you could apply there and, if accepted, you would get two year’s worth of time unobstructed by any other practical worries and considerations; they’d give you a place to live, if they liked your writing, and they might even waive your tuition, or you could apply for a student loan. All you had to do there was write.

So I applied to one of those programs – at the University of New Hampshire – and I was subsequently accepted, even despite the fact that I had not a single story in English finished by that time.

The rest was more or less clear sailing: I kept on writing in English, gradually getting better at it (as you get better at anything you do stubbornly and consistently and with passion); and eventually, one story got accepted for publication in a literary journal, and then another – and I was on my way, by and large.

Within a few months, an editor with a large publishing house had contacted me and asked if I might have enough stories for a collection, so I told her I’d have the needed number of stories by the time she needed them.¨

In due time, the book of my stories got published, I went to Stanford University on a post-graduate writing fellowship (the Wallace Stegner Fellowship); then I applied for a teaching job at the University of Minnesota, where there was an opening; I was hired by it for a two-year stint. Then I was lucky enough to have been awarded the prestigious Guggenheim fellowship in writing, which indeed is a coveted distinction to get, and one that makes getting jobs easier. I subsequently went on to teach at a number of colleges and universities, in the graduate and undergraduate writing programs (New York University, St. Lawrence University, Union College), before settling permanently in Montreal, which is home now.

That’s the whole story, in a nutshell.

As an émigré and especially as a native Russian language speaker writing in English you probably have to do a lot of cultural translation and adapting from one culture to another. How do you go about it? How do you feel about it?

I don’t think I do much of any such translation anymore, be it in the metaphoric or literal sense. (This, quite apart from the fact that the two languages are not compatible enough structurally to lend themselves easily to the process of instantaneous translation by the translation engine of one’s mind. To me, the oft-asked question, “What language do you think in?” – doesn’t really make much sense, since I don’t really think in words, as most people do not, either. The language of thought is separate from the language of words, thought made word.) I believe -- which is to say, I feel – I have found a place of balance for myself -- or rather, the process of my life itself has found such a place of psychological and intellectual balance for me.

I may, fancifully speaking, be suspended between two worlds, the old and the new one: the world of my past and that of my present, with one foot planted in the present and one in the past; and the past, of course, is also the present.

I feel that my first several years in the new world, which were quite hard and difficult, filled with doubt and nostalgia and despair – those were the years when this process of dividing myself into two selves was taking place. Which, basically, may be a way of me saying that there are two people cohabitating inside me: one belonging in the world of Russia, the other -- citizen of the larger, broader world.

I am very plugged in to the current developments in Russia, I follow them closely, I spend quite a bit of time every day on the Russian websites, I read the new literary publications in Russia, I speak to some very close friends from Russia, both living there and abroad; I still feel that Russia is home for me, in some esoteric way: and when I’m back in Russia, I understand the code of people’s living there, I feel that I belong there – although I no longer live and could never live there again. But my life’s center of gravity has long shifted towards the broader, larger world of my post-Soviet existence, my home is the world outside Russia. I am a citizen of the US and a permanent resident of Canada, but I feel that I live in a larger world than just that of North America.

That having been said, I am a professor of English who teaches the university-level creative writing and American short story; I read lots of contemporary American literature (albeit not as much as I would like perhaps), as well as my students and other young writers’ stories – hundreds of stories every year. Somehow, I manage to stay in one piece and not feel torn or conflicted within my own head and my own heart – but, again, this did not happen quickly or easily; as nothing really good ever happens in life quickly and easily, without some serious work one does, often unbeknownst to himself, to prepare himself for the kind of life that he feels makes sense.

Who are the star participants among this year’s faculty members?

All of them are stars in my book, as well as by the lights of great many readers in north America and abroad – although not in the same sense or scope as, say, Brad Pitt or Jennifer Lopez or the authors of mega-bestsellers on The New York Times bestseller list are stars. The literary world, at least in North America, is not about starship – there’re not enough readers of serious literature in modern world to make them stars in the commonplace meaning of the term – but it is, rather, about being consistently interesting and thoughtful and contemporary and doing meaningful things with one’s writing, charting new literary routes, taking reader to the place where serious questions about the serious life’s issues get asked… and not necessarily answered, because life itself is an open-ended proposition, with no ready-made answers or recipes for happiness on the offer.

One of the great advantages of being an independent literary program run by writers is that we’re free in our choice of invited faculty. Over the fourteen years of SLS’s existence, we’ve brought to our programs the veritable Who’s Who of the North American and international letters: people who are innately curious about the different paradigms of life in various places and who – although they easily could afford to come to those places on their own – Russia, Lithuania, Kenya -- wouldn’t be content with status of the mere tourists, which they inevitably would be without the familiarity with and immersion in the local literary and arts scene.

Another very distinct feature of SLS separating it from any other program of its kind: we draw no dividing lines between the well-known, famous and accomplished writers on the faculty -- and the beginning writers constituting the bulk of the program participants. Everyone’s in the same boat on the SLS programs; everyone’s in on the same type of discovery. Our programs are about shifting and accelerating the paradigm of one’s literary practice, and so we put people in highly unfamiliar (although on the surface recognizable) settings – and everyone is lost there in the company of other writers; everyone is lost within a findable context. Everyone is brought together by the pressure of the sheer strangeness, unfamiliarity of the surroundings. A very famous writer therefore can drink beer till two in the morning in the company of twenty-year-old undergraduate students of creative writing and talk to them as equals about literature… or whatever else people talk about at two in the morning while drinking beer Writing is an enterprise where the rank has no meaning. A famous writer is nothing but yesterday’s novice. Over the course of my teaching career, I’ve seen enough talented but not necessarily hard-working people, and enough not too brightly gifted (on the surface) yet extremely ambitious and serious and diligent your writers, to know that in writing, dedication to the process and practice of literature inevitably trumps the bright but sometimes shallow flame of natural talent. Talent is not always to be found on the surface of one’s early writing. People come into the possession of their talent, their true literary voices, over the long period of hard work.

This is the third time that you run the program in Vilnius. Why?

I am very glad we’re holding SLS programs in Lithuania now,. The idea to open one came after we had decided to suspend our sessions in St. Petersburg, which we ran for 10 years straight and brought roughly a thousand students to the city on the Neva. The constraints of available space would preclude me at this point from talking about the reasons why I’ve always found Lithuania fascinating – going back to the early years of my Soviet adolescence. But those reasons were indeed numerous, and memorable.

So I decided to see if we could hold a program in a place which, unlike St. Petersburg, Russia, is not that easily and readily recognizable to the North American literary community; does not hold the same kind of raw mystique perhaps that Russia possesses – not to mention Kenya, which is the site of another one of our long-running programs.

Lithuania, of course, is the geographic heart of Europe – but more than that, it is the spot where the tectonic plates of European history have clashed over the centuries, and currently are clashing as well; it is a place of transition from the old, divided Europe, to the new, unified yet still painfully unequal one.

To me, of course, it matters a great deal that this is a post-Soviet space – and of course, and very meaningfully, it is of essential importance to me that Lithuania was the place of the greatest concentration of Jewish people in Europe relative to the native population, for centuries and immediately prior to the WWII, and then became the site of the greatest tragedy in the history of the Jewish people. My ancestry, originally, is from the larger Litvak area: Belarussian border with Lithuania, and Latvia. There is a large agglomeration of factor that have caused me to want to hold the program here, both personal and intensely objective ones

One of the aims of the program is to set in motion a cultural, literary and, most importantly, creative exchange between the visiting established authors and writers to be and the local literary community. Based on previous SLS Vilnius, how does that work, does that collaboration bare any fruit?

We’re working on it. SLS, basically, over the years, without setting this as a major goal expressly, has positioned itself as a moveable platform of sorts upon which the North American and the international literary communities can meet. Over time, we have had lots of former SLS participants collaborating on literary projects with their counterparts from Russia and Kenya and Canada; and we‘re intent on seeing the same happen in the case of the Lithuanian literary community. There have already been some poetry translations of contemporary Lithuanian poetry done by our program participants, on a fairly significant scale, and some work already has been published. We’re looking to expand that effort further still, and on a considerable scale. We are bringing to Lithuania some of the leading publishing-house and literary-magazine editors, who always are interested in discovering the new voices from a variety of places. Ask me the same question in a year: after all, we have only just started our program in Lithuania: three years is a short time. Ars longa, vita brevis.

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - (0) Comment

How can Lithuania break out of the vicious circle?

Our article “Message to all U.S.-Lithuanians: Come home, your country needs you!”, has resulted in many reactions. Read the article HERE, and see some of the comments below.

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - (0) Comment

Viktorija Ruškulienė,

New Jersey, USA

I live with hope, that there will be a day, when I'll return home to Lithuania to stay there forever, and I still will be welcomed by some remaining friends and family.

Viktorija Ruškulienė

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - (0) Comment

Founded in Minsk in 1992, the European Humanities University (EHU) celebrates its 20th anniversary this year—its seventh in Vilnius—with a series of special events in Lithuania and several other countries, including Belgium, Denmark, Germany, Sweden, the United Kingdom, and the United States.

Belarusian European Humanities University, which is in exile in Vilnius, is preparing the next generation of Belarus, thus giving hope for an open society in the country based on liberal and democratic values

This was stated by Foreign Minister Audronius Azubalis on an annual Assembly of the EHU Trust Fund donors on June 5, dedicated to the 20th anniversary of the university.

"We believe that these young people will be able to properly participate in the development of the Belarusian society and will contribute to the country’s openness to the values of the Western world," said the Foreign Minister of Lithuania.

According to him, it is necessary to continue providing support to the EHU until it could be allowed in Minsk. Audronius Azubalis says the university is based on respect for the traditions of liberal education and combines the best ideas of East and West, as one of the most important transatlantic projects for the European future of Belarus.

"We are engaged in positive changes in Belarus through support of the EHU. This is our solid contribution to the future of the Belarusian society," said the Minister of Lithuania.

EHU was founded in 1992 in Minsk, but in 2005 it was forced to move into Vilnius under pressure of the country’s authorities. Today, the university has 1.800 students, mostly citizens of Belarus.

Source: http://telegraf.by/en

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

Kęstutis J. Eidukonis

Opinion: Kestutis J. Eidukonis, LTC USAR (ret)

As an experienced former Military FAO (Foreign Area Officer) I would like to make the following observations on the state of economic, political and social affairs in Lithuania. I have been coming here since 1992 and spend considerable time living here and observing the population, politics, social and economic situation in the country. I spend my time living in Vilnius and out in the countryside near Uzuguostis where I have gotten a priceless education on the views of the "kaimiečiai". I have family and friends in Klaipeda, Kaunas and Panevezys, I have talked to numerous Lithuanians who have emigrated to the US and other countries. I have a great love for Lithuania and its people and carry dual citizenship and firmly believe that if Lithuania gets its house in order it will become a wonderful country to live in. Its citizens will stop fleeing the country and actually start returning. But before this can occur we have to identify and solve some major problems.

1. The country is overtaxed

Because of the size of the governmental work force, the country is overtaxed. The 21% PVM, the Income Tax on companies and individuals, the Capital gains tax, the SODRA (Social Security Tax) and other hidden taxes and governmental subsidies cause the cost of goods and services to soar. Contrary to popular myth all these taxes are ultimately paid by the citizen consumer. Rough calculations indicate that 60 to 70% of the cost of any product or service is paid to the government by the consumer. This factor inhibits capital formation and job creation and impoverishes the citizenry and makes Lithuania uncompetitive in the world!

2. Because of these high taxes most small firms and individuals in Lithuania cheat and lie

Because of these high taxes most small firms and individuals in Lithuania cheat and lie on their taxes and in the sale of goods and services. I estimate that 50 to 60 % of the economy of Lithuania operates "under the table". This makes scofflaws out of most citizens in the country, thereby diminishing the respect for all organs of the government. It is also a widely accepted fact that if these firms and individuals operated "honestly" they would not survive. The government cannot arrest and prosecute 50 to 60% of the population and thus bribery and corruption become an endemic way of life. Only the politicians in their quest for more and more funds to feed this insatiable monster, seem totally ignorant of this factor. As this article is being written a Euro parliamentarian is proposing taxing ALL real estate and automobiles "because the rest of the EU does it and they have been urging Lithuania to also do it." The French are also proposing a "financial transaction tax". Lets see - taxes on smoking, drinking, financial transactions, sales of goods and services, real estate, cars, income, capital gains - my wise "kaimiečiai" acquaintances are quietly bemoaning the fact that if the government could they would soon be collecting a tax on peeing and defecating, and that the only reason there is no tax on sexual intercourse is because the government needs more tax payers-but let’s not give them any ideas!

3. One cannot hold accountable the various organs of government either

Because most citizens in the country cheat and lie on their obligations to the government, they cannot hold accountable the various organs of government either. "How can I complain about someone stealing from the government if I am doing the same thing?" Thus we tend to tolerate corruption in government and actually normalize it. This leads to a decline in the moral underpinnings of society as well as demoralization of the citizenry. It also leads to a lack of shame and further immorality. "It cannot be bad if everyone does it!" It discourages love of country, and fellow citizens. How can one love a country of crooks and cheats? Honest people are made to feel hopeless and powerless and thereby become apathetic. Those who feel like this become prime candidates for emigration. The drain on the country is palpable.

4. The lack of accountability in the government.

141 members of the Seimas makes for an unruly and unaccountable government. The election of the Seimas by parties makes the members of Parliament indebted to the party hierarchy rather than responsive to the electorate. The parties need funds to exist and thus become captives to special interests, oligarchs, and even other countries. This causes if not de-facto corruption, then the appearance of corruption. In proportion to the size of the country the size of the parliament is too large. 3 + million people do not need 141 parliamentarians and their entourage feeding at the public trough. Each parliamentarian represents about 22,000 inhabitants and thus 22,000 people have to support one parliamentarian and their entourage. The size of the parliament is too large in relation to the size of the population. The size of the government in relation to the size of the population is also too large. Lithuania is about the size of a large city and yet it has to support the infrastructure of a country - an army, diplomatic corps, roads, bridges, administration medical care for the population pensions as well as the infrastructure of numerous cities and counties. etc. It is impossible for such a small population to support such a large infrastructure and still expand capital and job formation. There will never be enough funds generate to feed this large apparatus. The infusion of funds from the EU is the only reason Lithuania has not gone the way of Greece. This situation cannot continue and sooner or later will have tragic consequences for the country. We cannot tax ourselves out of this.

5. We have adapted all the bad attributes of Greece

We have adapted all the bad attributes of Greece without the infrastructure and work underpinnings of Germany. Our government is as effective as Italy's and Greece's and we will sooner or later follow them into the same kettle.

The European Union's funds have come with strings attached that have further debilitated our economy and moral fiber. We have paralyzed our farms and woodlands with subsidies, false economies, bureaucratic red tape and socialistic policies which favor French and German farm interests over Lithuanian interests. While the Germans got in bed with Russia at our expense with the Baltic Sea pipe line, we have closed down our nuclear power plant before replacing it with a new one leaving us dependent on Russia for our energy needs. Our defiance of Russia is being punished with higher gas, oil and electric prices.

It is fine to find fault and criticize, but ultimately we need to find solutions for our problems. Lets analyze our strengths and overcome our weaknesses.

1. Lithuanian's geographic location has been one source of our misfortune.

We are located between two great powers - Russia and Germany. Earlier in history they have fought each other by rampaging through our country. Now they are economic allies, ignore us and bypass us, and punish us economically when we do not do their bidding. This geographic reality is inescapable, but we need to use it to our advantage. We need to become the Hong Kong of Russia without being swallowed up by it. We have a great seaport - good rail. We are the rail transfer point. All this needs to be exploited for our advantage.

2. We need to become energy independent.

The Ignalina power plant needs to be built. The gas liquefaction terminal and storage area needs to be completed and set up - the quicker the better. The pipeline to Klaipeda from Mazeikiai needs to be set up to work both ways both for the import of oil and the export of refined product.

3. We need to keep the Litas - do not adopt the Euro.

If we do, we loose control of our economy, but we need to let the Litas float against the Euro. Fix the price of the Litas to gold if possible. It will make the Litas a currency as sought after as the Swiss Franc and keep inflation in check.

4. Cut the size of Government.

Everything that can be needs to be privatized. The government is not the best manager of anything. Privatization will not solve government bloat. We also need to drastically cut the government's payroll, starting with the parliament. Cut parliamentarian's pay in half and cut the number of parliamentarians to about 45-50 to correspond with administrative and municipal districts. Have direct election of parliamentarians - no more voting for parties. Fractions will hopefully form to form governments and work for the good of their home regions as well as the welfare of the country. Have term limits. We do not need to have professional politicians. The politicians also need to go back and live under the laws and taxes they have passed.

5. Re-constitute the government to be incorruptible, functional and accountable.

This is a whole chapter in itself and needs to be covered separately, but it desperately needs to be done.

6. Cap all corporate and private income tax at 5%

7. Lithuania should have only one tax

Lithuania should have only one tax - easy to calculate 10 to 15 % tax on consumption only. This would fix the maximum rate of taxation at 15%.

8. Privatize the Social Security system aka Chile.

9. Make available private Health Insurance for the upcoming generation.

10. Root out corrupt individuals from all branches of government

Root out corrupt individuals from all branches of government - the citizenry will be glad to assist in this endeavor.

11. Reeducate the citizenry and youth in citizenship, patriotism and the judeo-christian ethics.

Last but not least reeducate the citizenry and youth in citizenship, patriotism and the judeo-christian ethics. Lithuania should declare itself a christian country which is also tolerant. The EU has become a secularly focused institution without a moral anchor. As anyone who has tried, can tell you, the search for strictly material well being is by itself an exercise in futility. Having worked with the Mennonites and Amish communities in the US, I can tell you that there is something to be said for the simple life. The most important values of God, Family and Country need to be reemphasized in our media, and educational system.

Lastly, nothing I have mentioned here is very original or insightful, but putting them all together to work together is essential. None of the suggestion can work on their own. It is a systems approach that has to be instituted to make it work.

Kestutis J. Eidukonis

LTC USAR (ret)

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - (0) Comment

If Lithuania gets its house

in order it will become a

wonderful country

Kęstutis J. Eidukonis

Opinion: Kestutis J. Eidukonis, LTC USAR (ret)

As an experienced former Military FAO (Foreign Area Officer) I would like to make the following observations on the state of economic, political and social affairs in Lithuania. I have been coming here since 1992 and spend considerable time living here and observing the population, politics, social and economic situation in the country. I spend my time living in Vilnius and out in the countryside near Uzuguostis where I have gotten a priceless education on the views of the "kaimiečiai". I have family and friends in Klaipeda, Kaunas and Panevezys, I have talked to numerous Lithuanians who have emigrated to the US and other countries. I have a great love for Lithuania and its people and carry dual citizenship and firmly believe that if Lithuania gets its house in order it will become a wonderful country to live in. Its citizens will stop fleeing the country and actually start returning. But before this can occur we have to identify and solve some major problems.

1. The country is overtaxed

2. Because of these high taxes most small firms and individuals in Lithuania cheat and lie

3. One cannot hold accountable the various organs of government either

4. The lack of accountability in the government.

5. We have adapted all the bad attributes of Greece

It is fine to find fault and criticize, but ultimately we need to find solutions for our problems. Lets analyze our strengths and overcome our weaknesses.

1. Lithuanian's geographic location has been one source of our misfortune.

2. We need to become energy independent.

3. We need to keep the Litas - do not adopt the Euro.

4. Cut the size of Government.

5. Re-constitute the government to be incorruptible, functional and accountable.

6. Cap all corporate and private income tax at 5%

7. Lithuania should have only one tax

8. Privatize the Social Security system aka Chile.

9. Make available private Health Insurance for the upcoming generation.

10. Root out corrupt individuals from all branches of government

11. Reeducate the citizenry and youth in citizenship, patriotism and the judeo-christian ethics.

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - (0) Comment

The medals of

Petras Rimsa

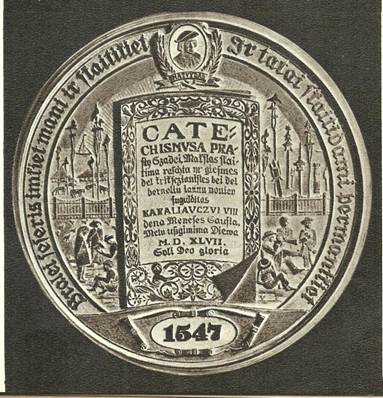

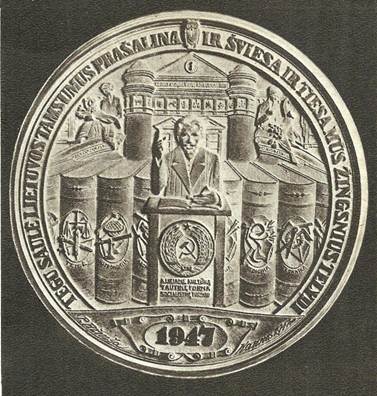

Lithuanian medallic art is an especially interesting area of study in the numismatic hobby. Individual medals struck by various persons or groups convey the specifics of the history of Lithuania and its people.

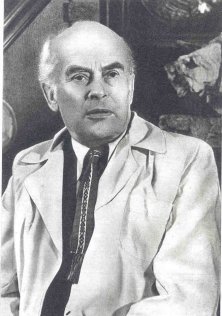

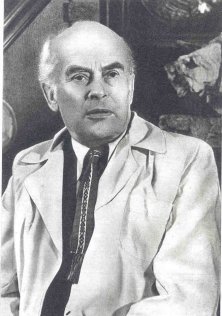

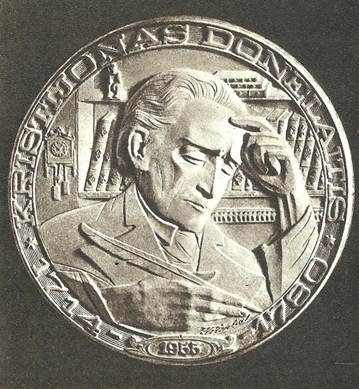

Petras Rimsa in 1957

By Frank Passic, Albion, Michigan

Lithuania’s most outstanding medalist was sculptor Petras Rimsa (1881-1961), a contemporary of Germany’s medalist Karl Goetz. Many of Rimsa’s designs reflect Lithuania’s patriotic themes and range from religious subject matter to sarcastic political commentary. Since the reestablishment of Lithuanian independence in the 1990s, Rimsa’s medals have again become popular and highly sought after by Lithuanian collectors. To meet the demand, there are even contemporary reproductions of Rimsa’s early 20th century medals.

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - (0) Comment

The medals of

Petras Rimsa

Lithuanian medallic art is an especially interesting area of study in the numismatic hobby. Individual medals struck by various persons or groups convey the specifics of the history of Lithuania and its people.

Petras Rimsa in 1957

|

By Frank Passic, Albion, Michigan Lithuania’s most outstanding medalist was sculptor Petras Rimsa (1881-1961), a contemporary of Germany’s medalist Karl Goetz. Many of Rimsa’s designs reflect Lithuania’s patriotic themes and range from religious subject matter to sarcastic political commentary. Since the reestablishment of Lithuanian independence in the 1990s, Rimsa’s medals have again become popular and highly sought after by Lithuanian collectors. To meet the demand, there are even contemporary reproductions of Rimsa’s early 20th century medals. Petras Rimsa was born November 11, 1881, in the Lithuanian village of Naudziai. His parents were farmers of the Suvalkai Province under Czarist rule, and in this rural setting young Petras aspired to be an artist. He was especially talented and showed a marked tendency for work that required skill, accuracy and patience. As a young boy he spent much of his leisure time whittling and decorating household articles and farm implements. Before long he had acquired the name of “Master” in his village in recognition of his artistic work. At the age of 17, Petras left his village for Warsaw, Poland, to study art under the tutelage of Polish sculpture Welonski. He then traveled to France to further study at the Ecole des Beaux Arts under Professor Antoin Mercie. After completing his courses there, Rimsa traveled to various European centers of art and culture, continually increasing his knowledge and skill.

Upon his return to Lithuania in 1906, Rimsa immersed himself in local Lithuanian cultural activities, helped to establish the Lithuanian Art Association and participated in the first Lithuanian Art Exhibit in 1907. Here he exhibited his most famous sculptural work, “The Lithuanian School,” (also known as the “School of Misery”) which received much critical acclaim. This masterpiece represents the Lithuanian school between the years 1864 and 1904 when the Russian government placed the strictest ban on Lithuanian literature. The sculpture shows a mother secretly teaching her child the Lithuanian language. The alert and watchful dog beside the child shows the constant fear with which the school operated. In 1993 the Bank of Lithuania illustrated Rimsa’s “Lithuanian School” on the back side of the 5 litai banknote designed by artist Gedrius Jonaitis and printed by the Thomas De La Rue printing company. Ironically, Rimsa had submitted sketches to the Bank of Lithuania for a proposed 50 litas banknote design during the 1920s in which he illustrated the “Lithuanian School” on the face. That design however was rejected at the time by bank officials.

P-55 1993 Lithuania 5 Litas banknote back side featuring the “Lithuanian School.”

In 1907 Rimsa exhibited his other famous work, Artojas (The Ploughman) which expressed Lithuania’s utter misery under Russian occupation. The piece depicts the ploughman with his beast of burden and the plough made by his own hands as they together force the hard and weedy soil to yield a crop. The Ploughman associated Rimsa’s name with Lithuania’s struggle for national independence. In 1911, the Russian Imperial Society of Arts awarded him a large cash prize for this work. Rimsa’s work THE PLOUGHMAN, created in 1922, graphically depicts the country’s misery under Russian occupation.

The outbreak of World War I brought severe hardships to Rimsa and his countrymen, and Rimsa was forced to labor in munitions factories and as a merchant. After Lithuanian independence was restored in 1918, he returned to his home in the Lithuanian capital of Vilnius and continued his artwork.

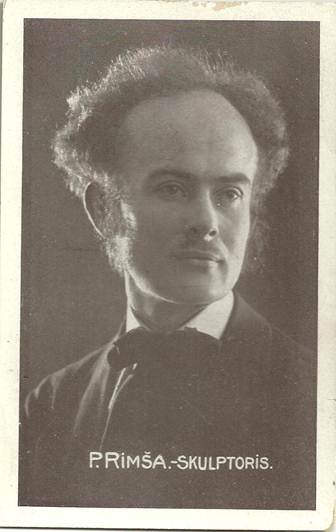

Petras Rimsa in the 1920s

His return to Vilnius, however, was short-lived. In 1920 the military invasion of Lithuania by Poland and occupation of Vilnius by Polish troops forced Rimsa to flee the city. His studio was lost and a lasting bitterness about the situation was implanted, a passion that was later reflected in his medallic work. After losing his studio in Vilnius, Rimsa journeyed to Berlin and other European cities. He finally returned to Lithuania and made his home in Kaunas, the temporary capital of the country.

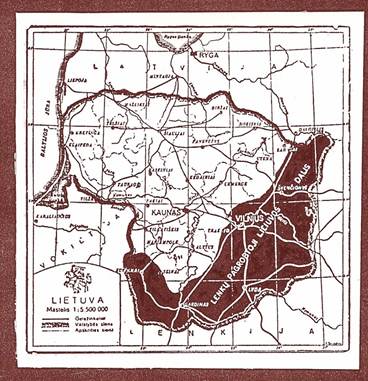

The portion of Lithuania occupied by Poland 1920-1939. Accordingly, when the subject of the Polish occupation of Lithuania’s capital came up in conversation, Rimsa suddenly became very eloquent and spoke as an expert on the subject. Rimsa toured the United States in 1936 and 1937, exhibiting his works in Boston, Chicago, Cleveland, Detroit, Pittsburg, New York and other cities. Critics marveled at his artistic abilities. Paul Bird of The Art Digest commented, “An artist of unusual graphic power, he also produces ornate linear sculptures, decorated from head to foot with fantastic designs.” Carlyle Burrows of the New York Herald Tribune wrote, “Medals like these celebrating the Congress of Vilnius, and the establishment of the first ecclesiastical province of Lithuania are forcefully modeled in their essential details, while showing meticulous elaboration of the backgrounds.” Eleanor Jewett of the Chicago Daily Tribune remarked, “There seems, in fact, no end to the genius of this artist. He cannot be classified as a modern or non-modern, but ranks with the unticketed immortals.” In the introduction to the official programs at the exhibition held at the International Institute in Boston, January 30 through February 12, 1937, the Consul General of Lithuania, Jonas Budrys, remarked: “Petras Rimsa is one of the most prominent sculptors of Lithuania. His creations are valued very highly not only in Lithuania, but also elsewhere. They portray the spirit of national Lithuanian art, they carry one into the realms of the unknown, unexplored futurism...His numerous medallions disclose the finesse of an accomplished artist. In appreciation of this recognition, and in appreciation of the talents of the sculptor, we offer this exhibit to art lovers, and we hope that it will tend to bring the American public closer to Lithuanian talents, and to the Lithuanian people as a whole.” 1 Rimsa’s success in the United States was due largely to the efforts of the noted Lithuanian-American numismatist, Dr. Alexander M. Rackus (1893-1965). An avid collector, Rackus belonged to the American Numismatist Association and wrote numerous articles for the Numismatist in the 1920s and 1930s. In his recollections, Rimsa remarked:

Dr. Aleksandras M. Rackus (1893-1965) “Aleksandras Rackus was the first collector with such a strong passion that I had met and knew. Of course, he had set his heart on my medals. They were items which, if was said, could be shown anywhere in the world. And Dr. Rackus took my medals to coin shows everywhere in the world. They were discussed quite often in American numismatic conventions. And it was worthwhile ... My medals apparently attracted the notice of Americans. Rackus wrote, “Visitors to numismatic shows, passing indifferently by other exhibits, would always stop at those cases in which were displayed Petras Rimsa medals, and enjoying themselves would remain by the half-hour.” Even American sculptors eyed them approvingly. As an example, the sculptor-medalist J. Henris Ripstra wrote me on April 18, 1931, as follows: “I recently viewed your medal collection, exhibited by Dr. Al. Rackus as the Chicago Coin Club. They pleased me very much, and I congratulate you upon your style and technique. If possible, I would like to acquire a collection of those medals.” And thus my medals found their way into the world.” 2 Following World War II, Rimsa stayed in Soviet-occupied Lithuania, where the communists gave him a large studio to replace his cramped one in Kaunas. Rimsa continued to illustrate books, write and design medals. Unhappy with the Soviet system, he frequently refused work in his later years, officially blaming his “old age,” as his personal letters to the West revealed. Rimsa died in Vilnius on October 2, 1961. His recollections were published in 1964, Rimsa’s pre-World War II medals were struck by Huguenin Freres & Company of Le Locle, Switzerland. This firm also manufactured Lithuanian military orders and decorations. Rimsa’s medals were struck in bronze, in various sizes of 100, 75, 60, 35 and 25 millimeters in diameter. Personal editions presented to close friends or dignitaries were often of silver or gold wash, and Huguenin Freres & Company customarily presented Rimsa with a 150-gram gold striking of each of his designs. On a personal note, in 1979, this writer was able to view various Rimsa medals on public display inside the “Stained Glass Museum” (The Church of Saint Michael the Archangel) in Kaunas, during my visit to Soviet-occupied Lithuania. I was also able to view Rimsa medals in private collections. Later I learned that my maternal great-grandmother was a Rimsa, although probably not related to the sculptor. Although I have only been able to obtain just a couple of his medals for my collection, I have still been fascinated about the details found on these medals, and the diversity of themes that the sculptor tackled. In May, 1983 the American Numismatic Association published my listing of Rimsa medals in their magazine The Numismatist. A close-up of the Congress of Vilnius medal was featured on the front cover. Cover of The Numismatist, May 1983 featuring Petras Rimsa medal detail.

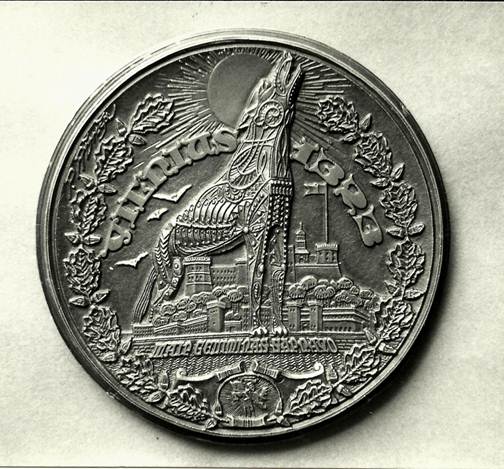

The following is a listing and description of the medals of the famous Lithuanian medalist, Petras Rimsa. 1. Vilnius, Capital of Lithuania This medal commemorates the 600th anniversary of the founding of the Lithuanian capital city of Vilnius. The anniversary occurred in 1923 when the city was under Polish occupation. VILNIUS, CAPITAL OF LITHUANIA Known Mintages: 35 centimeter medal, private issue, only a few struck; 75-millimeter medal—300 struck; 20 100mm personal specimens cast in bronze. Obverse: Featured is Grand Duke Gediminas, dressed in chain mail and holding a downward pointing sword in his right hand. On his left shoulder is a decorative mask of a lion’s head, symbolic of Gediminas reputation as the “Lithuanian Lion.” Gediminas began the dynasty of Lithuanian rules that lasted almost 300 years. Ruling from 1316 to 1341, Gediminas completed the unification of the Lithuanian tribes and expanded the territory of the nation. The inscription reads GEDIMINAS DIDYSIS LIETUVOS KUNIGAIKSTIS MCCCXVI-MCCCXLI, which translates “Gediminas the Great, Grand Duke of Lithuania 1316-1341.” Reverse: Shown is Gediminas castle, the ruins of which are still found in Vilnius today. The inscription reads VILNIUS LIETUVOS SOSTINE, meaning “Vilnius, Capital of Lithuania.” At the bottom is Vytis (the knight), Lithuania’s national emblem, and the anniversary dates, MCCCXXIII-MCMXXIII (1323-1923). Rimsa also produced a plaque featuring the Gediminas design.

Gediminas plaque 2. Regaining Klaipeda In 1252 the Livonian Order invaded western Lithuania, reached the Courish Lagoon and erected a stronghold on the site of a native Lithuanian village. Pope Innocent IV noted in 1253 that the stronghold had clearly been built in Lithuanian territory. Renamed “Memelburg”, the city was a source of boundary conflicts between Lithuania and the Teutonic knights and other warring factions for many centuries. After World War I, the Klaipeda region was placed under Allied control and Lithuanians feared the city would be returned to the Germans or taken over by Poland. In January 1923, the Lithuanians staged an insurrection and successfully regained the city. Known Mintages: 10,000 specimens were struck in 1927, some 60 millimeters in diameter and the remainder 35 millimeters. In addition, two personal editions were issued.

Obverse: Shown is a Lithuanian of the Klaipeda district (right) calling to arms a volunteer of independent Lithuania (left). The center depicts the defender of Lithuania receiving a sword from a patriotic woman, with the city in the background. Surrounding this is the inscription, KAS MUSU KOVA IGYSIM, which translates “that which is ours we shall fight to retain.” In the left oval is the Vytis emblem, opposite is the coat-of-arms of the city. The bottom contain a sword pointed upward, with the words, I-9 KLAIPEDA 1923, referring to January 9, 1923, when the call for help went out. A wreath of oak leaves surrounds the design, and the emblem of the Lithuanian Riflemen’s Union, the double-barred cross, appears above.

Obverse Reverse: Shown is Klaipeda after reunification. Major Lithuania (left) joins hands with Minor Lithuania (right), representing unity of the land and waters of Lithuania. In the center, the defender has returned, and is being bestowed with the laurel wreath of victory and honor. At the bottom is a downward pointed sword with the inscription 1-19 KLAIPEDA 1923, signifying the day of the insurrection. Below are twigs from the Lithuanian national flower, the ruta (rue). In the let oval is a sailboat, symbolic of the recreation of the area; opposite is placed a rake and a plow, symbolic of the industry and agriculture of the area. At the top of the medal is the Order of the Cross of Vytis, Lithuania’s highest military order for honorable service at that time. The legend reads ISKOVOTA-MYLET MOKESIM, which means “That which we have regained, we will know how to cherish.” Rimsa later issued another version of the medal with the inscription AMZIUS BUDEJE LAISVE LAIMEJOM, which translates “having waited for ages, we won freedom.” Specimens with the alternate inscription also bear the date 1-20 on the bottom, signifying the day victory was achieved. The obverse of the later version bears the inscription VADOUKIS PATS, IR BUSI LAISVAS which means “Save Yourself and you Will be Free.”

Reverse

Rimsa’s Signature on the Klaipeda Medal.

3. Congress of Vilnius Following the Revolt of 1905 in the Russian Empire, Lithuanian nationalists, concerned with the question of autonomy for Lithuania, gathered in Vilnius on November 21-22, 1905. Headed by Jonas Basanavicius, the 2000 member assembly resolved that the Czar was the enemy of Lithuania, that Lithuania should be autonomous, that Russian influences in Lithuania must be removed and that the Lithuanian language and culture should reign supreme in the country. Within a few weeks after the assembly dispersed, Lithuanians held elections, ousting Russian officials. However, the Russian government soon enacted repressive measures against those who had been active in carrying out the resolutions. This medal commemorates the 20th anniversary of the Congress of Vilnius.

Obverse: The design focuses on the outline of the city of Vilnius, with the Hill of Gediminas in the background. The inscription reads, DIDYSIS VILNIAUS SEIMAS, which means “The Great Congress of Vilnius.” At the top is the phrase from the Lithuanian national anthem: IS PRAEITIES TAVE SUNUS TE STUORTBE SEMIA, which translates “may your sons draw strength from the past.”

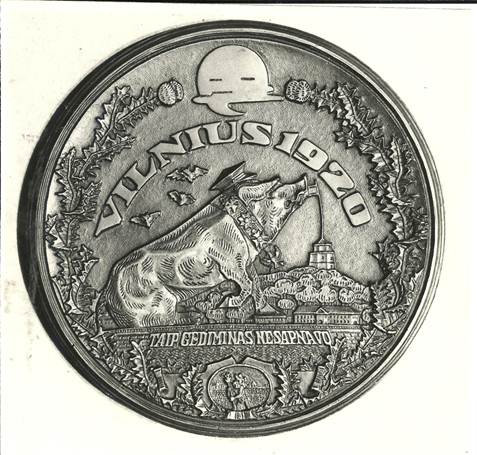

Reverse: At the top is the date 1925. Depicted is independent Lithuania standing before her throne, holding the national emblem Vytis. The chain of slavery is at her feet, and the lion at her side represents strength. Her left arm rests upon the shield with the double-barred cross, the emblem of the Lithuanian Riflemen’s Union (Lietuvos Sauliu Sajunga), and bears its initials, “L.S.S.” 4. Vilnius in 1323; Vilnius in 1920 This is the first of several anti-Polish medals issued in protest of the Polish occupation of Vilnius.

Reverse

Reverse: In sharp contrast with the obverse, the scene depicts Vilnius in 1920 after it was seized by Poland. At the base of the castle ruins is inscribed TAIP GEDIMINAS NESAPNAVO, which means “this was not Gediminas’s dream.” The center is dominated by a large pig furiously devouring the Lithuanian flag. The collar of the pig is adorned with Polish military symbols. The pig is wearing a militaristic-style hat, representing the treaty violation and method used to seize the city. To the left, instead of three birds, hover three bats, signifying the evilness of the pig’s presence. The legend reads VILNIUS 1920. The sun has been replaced by a dark moon, and the design is surrounded by a wreath of thistles and thorns. At the bottom is the coat-of-arms of Vilnius. Rimsa also printed and circulated postcards with this same theme, and one is illustrated here.

Rimsa postcard

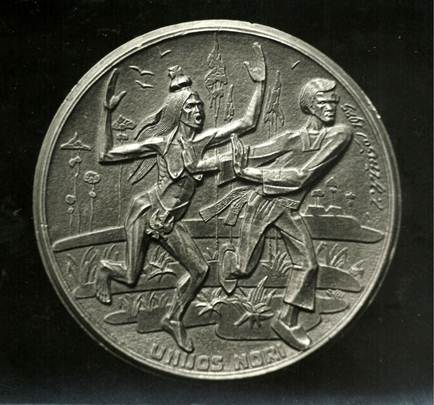

5. Unity and War This medal, entitled Unity and War (Unija ir Kova), resurrects Lithuanian numismatic history as a theme of conflict between the Lithuanians and the Poles when referring to the occupation of Vilnius by Poland.

Obverse: Depicted is the Lithuanian 3 grosz coin of 1565, minted during the reign of Grand Duke Sigismund August. This coin is one of the most famous in Lithuanian numismatic history. When minted, it was an international embarrassment to the Poles, and a strong expression of Lithuanian autonomy. On this coin, the Vytis emblem was transferred to the obverse side of the coin, and the monogram of Sigismund August (where formerly the bust of the ruler was displayed) was transferred to the reverse between the date numerals at the bottom. In Latin on the reverse is the biting sentence from the Psalm of David: QUI HABITAT IN COELIS IRRIDEBIT EOS (Psalm 2:4), which means “He who sits in the heavens laughs at them.” This passage was purposely included on the coin by officials at the Lithuanian Mint as a response to Polish clamoring about the Lithuanian 3 grosz having twenty percent more intrinsic value than it’s Polish counterpart, and for placing Lithuanian symbols and inscriptions in prominent positions on coins minted in Vilnius. Jonas K. Karys, director of the Lithuanian Mint from 1936-1939 wrote on the subject by stating: “So the leadership of the Mint and eminent Lithuanians standing in back of it in Vilnius, on at least one occasion gave the Poles what was coming to them. The Poles, full of outrage, descended upon Sigismund August, who in this case was least at fault. When those 3-grosz coins appeared in Polish provinces, the storm boiled over. The bishop of Cracow, F. Krasinski supported the indignation of the Polish boyars, and sent a special letter addressed to Sigismund August. Having received that letter, the ruler personally investigated the case and at the beginning of 1566, totally banned further striking of that coin.” 3 The coin depicted on this medal bears the Gumowski number G-623 and was minted in 1565 and 1566.

1566 3-grosz, satirical side.

The image of the coin appears in the center of the medal. At the top of the medal is a favorite Polish proverb WOLNIZ WOLNYMI; ROWNIZ ROWNYMI, which translates “the free with the free, equal with equals.” Accordingly, the phrase is separated by a mask, signifying the hypocrisy of the Polish words. Instead of the two nationalities being equals, the Polonization of Lithuania subsequently occurred. This was especially true during the period of the occupation of Vilnius by Poland, when Lithuanian schools, customs, and organizations were squelched, and leaders imprisoned. At the bottom is shown a dog and a cat, which represent the incompatibility of the union. The word UNIJA appears at the very bottom of the edge. To the left in an oval space is found the Polish eagle; opposite is the Lithuanian emblem, Vytis. Reverse: Entitled KOVA (war) on the bottom rim, this scene depicts Vytis in combat with the Polish eagle. It is the prophecy of the minters of 1565 fulfilled. The dog and cat, represented only by heads on the side rims, are incompatible and far apart. Rimsa’s signature appears at the three o’clock position, and the date 1925 appears at the two o’clock position.

UNITY AND WAR, Reverse.

1566 3-grosz, Vytis side.

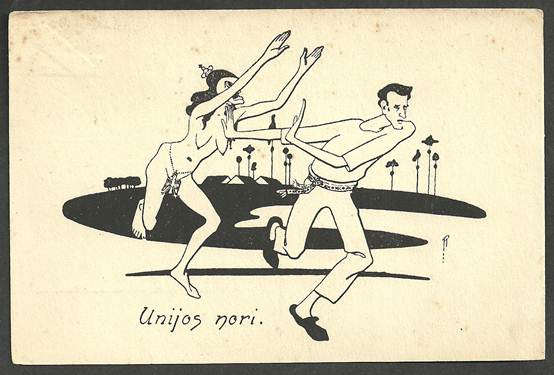

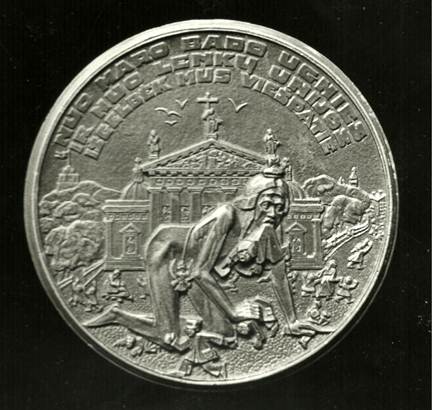

6. Union Desired

Known Mintage: Only 12 specimens are estimated to have been struck, all 100 millimeters in diameter. Bronze plaques are also known to exist. Obverse: Entitled UNIJOS NORI (Union Desired), this extremely grotesque theme represents a naked and prostitute Poland offering herself forcibly to a fleeing Lithuanian male in national costume. Rimsa’s signature and the date 1925 are located at the two o’clock position. This same scene was also circulated on postcards produced by Rimsa, one of which is illustrated here.

“Union Desired” postcard produced by Rimsa.

Reverse: Depicted is the Union rejected, with Poland exterminating all that is Lithuanian in Vilnius. In 1925, the Polish occupational regime began an assault on Lithuanian school children for their outspoken nationalism. As a protest, Rimsa graphically portrayed the same deranged Polish figure devouring innocent Lithuanian school children in front of the famous Cathedral of Vilnius. The children are shown fleeing from the Polish terror. The legend reads NUO MARO BADO UGINIES IR NUO LENKU UNIJOS ISGELBEK MUS VIESPATIE, which translates “from pestilence, famine, fire and union with Poland, Deliver us O Lord!”

Reverse

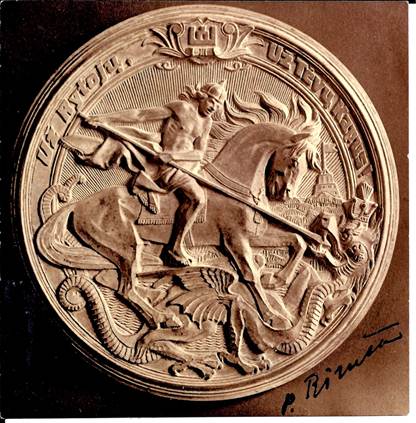

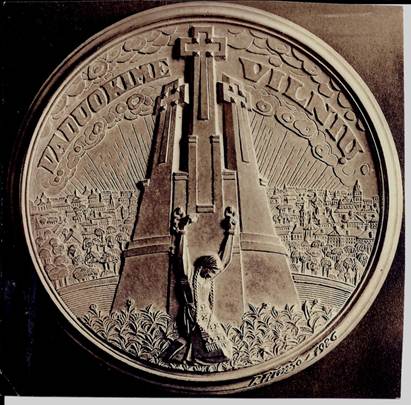

7. Let us Liberate Vilnius Obverse: Vytis is shown in violent combat, spearing the Polish dragon, with the Hill of Gediminas on the right. The top inscription is separated from the Columns of Gediminas emblem, and reads UZ RYTOJU – UZ TEVU KAPUS! which translates “For the Future – for the Graves of our Ancestors!”

Obverse

Reverse: Portrayed is the monument Three Crosses, which stands on the high Bare Mountain on the steep right bank of the Vilnia River. This monument was erected in the early 17th century and remained a permanent feature of the cityscape until 1869, when it was destroyed. After World War I, artist Anton Wiwulski designed a new monument that was painted in white. This monument was blown up by the communists in 1950. It has since been recreated. The legend VADUOKIME VILNIU, which translates “Let us Liberate Vilnius,” appears at the top, with Vilnius in the background. Below is maiden Lithuania, who is chained to the monument amidst a bed of ruta. She is awaiting Vytis to save her from Poland. At the five o’clock position appears Rimsa’s signature and the date 1926.

Reverse

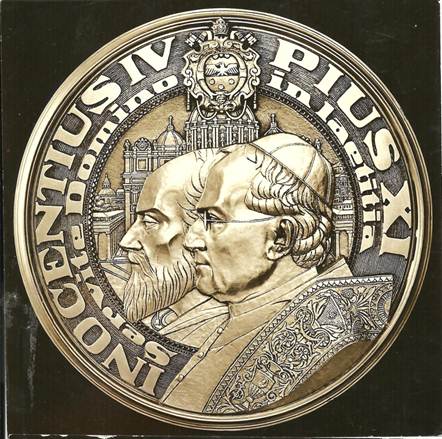

8. First Ecclesiastical Province of Lithuania During the era of the Republic of Lithuania, not all the Lithuanian-inhabited areas were included because of the large areas occupied by Poland. Roman Catholic Lithuanians sought to prevent the Holy See in Rome from recognizing Polish military conquests, but were unsuccessful. The archdiocese of Vilnius was transferred to Poland, and the Poles forced Lithuanian Bishop Jurgis Matulaitis to resign. In order to appease the Lithuanian church, Pope Pius XI raised Matulaitis to the office of titular archbishop and named him apostolic visitation to Lithuania, with the Metropolitan See located in the temporary capital of Kaunas. The ecclesiastical province of Lithuania received an official blessing from Pope Pius XI on April 26, 1926. Rimsa’s medal was issued in commemoration of the first ecclesiastical province of Lithuania. Lithuania first became a Christian nation in 1251 when Lithuania’s Mindaugas entered into relations with the Holy See, and Pope Innocent IV established the diocese of Lithuania. In 1252 Mindaugas was crowned King of Lithuania, in the name of Pope Innocent IV, who declared him to be a “special son of the Holy Roman Church.” Obverse: In the center of the medal are the images of Pope Innocent IV (left) and Pope Pius XI (right) who founded respectively, the first Bishopric and the first Metropolitan See in Lithuania. In the background is the Bascilica of St. Peter in Rome, and at the top of the personal insignia of Pope Pius XI.

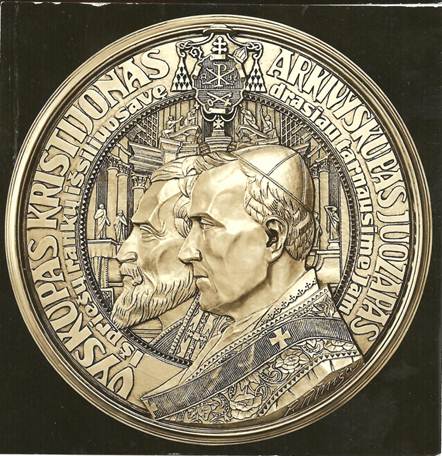

Obverse Reverse: Featured is the image of Bishop Kristijonas (Christian) (left), the first Lithuanian bishop, who received his appointment from Pope Innocent IV on July 17, 1251. Prior to his appointment Kristijonas was a priest of the Teutonic Order under the German archbishop of Riga. Kristijonas established his See in the pagan Samogitian region of Lithuania, but only remained until 1259 when he left for Germany and ended his days in 1270 as a suffragan bishop of Mainz.

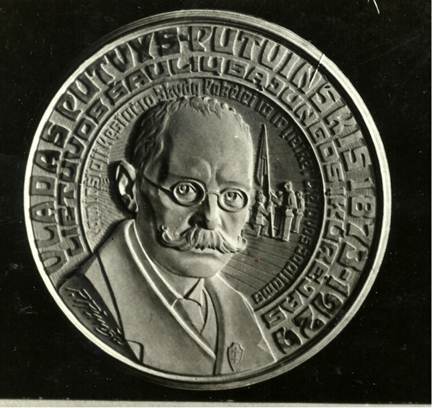

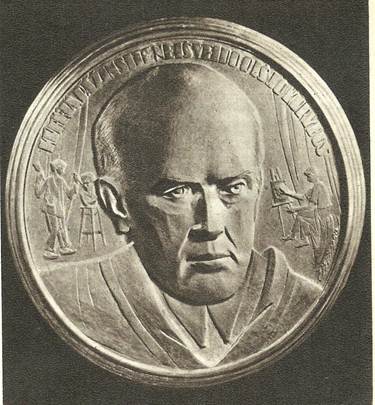

On the right is the image of Archbishop Juozapas Skvireckas (1873-1959), the first Archbishop of Lithuania. Skvireckas was a well-known scholar and the theologian who translated the Bible into the Lithuanian language. He governed the Kaunas archdiocese for almost the entire period of Lithuanian independence. He fled Soviet-occupied Lithuania in 1944 and went to a convent in the Austrian Alps, where he lived until his death. The arms of Bishop Juozapas disappear at the top of the medal. The inscription reads, IS PRIESU RANKU ISSILIUSAVE DRASIAU TARNAUSIME JAM, which translates “having liberated ourselves from the enemy’s hands, we shall serve with more courage.” The names of the two men appear around the perimeter of the medal. 9. In Honor of Vladas Putvys-Putvinskis This medal was issued in honor of the founder of the Lithuanian Riflemen’s Union (Lietuvos Sauliu Sajunga), Vladas Gerardas Putvinskis-Putvys (1873-1959). Putvys was descended from an old Lithuanian noble family, and his estates became important centers for secret Lithuanian activities in the late 19th century. He founded the Riflemen’s Union in 1919 and was elected its first president and commander-in-chief. Obverse: Shown is the image of the late organizer. In the background is depicted the ceremony of the presentation of the colors. The legend reads VLADAS PUTVYS-PUTVINSKIS 1873-1929, LIETUVOS SAULIU SAJUNGOS I KUREJAS, which translates “Vladas Putvys-Putvinskis 1873-1929, founder of the Lithuanian Riflemen’s Union.” A smaller inscription in the center circular area translates, “thou has raised the forgotten shield of Kestutis and presented it to the Lithuanian Riflemen’s Union.”

Obverse Reverse: At the top is the Vytis emblem, opposite of which is the Columns of Gediminas. In the center is the insignia of the Riflemen’s Union, which was designated by Rimsa. The inscription reads IR SIRDI IR PROTA TEVYNES RYTOJUI, which translates “both heart and mind for the nation’s future.”

Reverse 10. Vytautas the Great Lithuania’s greatest patriarch, Vytautas the Great, reigned as Grand Duke of Lithuania from 1392 to 1430. Vytautas expanded Lithuanian territory and made it one of the leading European powers of his day. He led the Lithuanian army and allies to a spectacular victory over the Teutonic Knights at the epoch-making battle of Zalgiris/Tannenberg/Grunwald in 1410. This event stopped the advance of the Knights, assuring independence for Lithuania and other eastern European nations. The Vytautas the Great medal is Rimsa’s most well known. Struck in many sizes (the original was 35 millimeters), this medal has the largest mintage of all Rimsa’s medals: 17,000 total. The obverse design became the emblem for the 500th anniversary celebration of the patriarch’s death. During Rimsa’s 1936-1937 tour of the United States, he presented a specimen of the Vytautas medal to the American Numismatic Association. Obverse: Shown is the image of Vytautas the Great. The legend reads VYTAUTAS DIDYSIS 1430-1930, which translates “Vytautas the Great 1430-1930.” In the background is depicted the Battle of Zalgiris/Tannenberg/Grunwald, similar to that which is found on Polish artist Jan Matejko’s famous rendition of the battle painted in 1878.

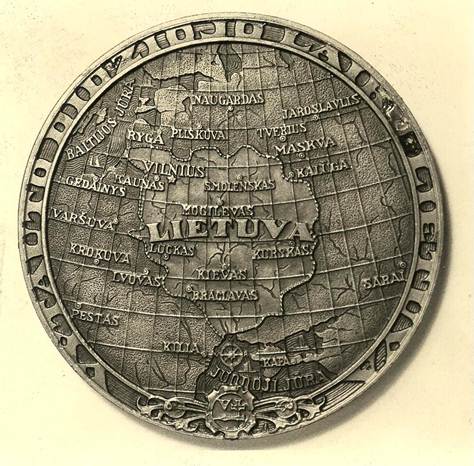

Reverse: Featured on the reverse is a map of Lithuania in the time of Vytautas. During the 15th century Lithuania stretched from the Baltic to the Black Sea, covering 350,000 square miles. Names of the cities are in Lithuanian. At the bottom appears the “Vytautas Symbol,” a popular emblem in 1930 based upon supposed ancient denars struck during Vytautas’s reign. The legend reads VYTAUTAS DIDZIO LAIKU LIETUVA, which means “Lithuania in the time of Vytautas the Great.”

Reverse

11. Riflemen’s Union Star Medal The Riflemen’s Union Star Medal was issued in 1939 as a decoration for the Lithuanian Riflemen’s Union. Each medal was presented with a blue/green ribbon with two white stripes. Accompanying each medal was a presentation certificate that included a likeness of the medal. The certificate presented to Dr. Alexander M. Rackus, translates: “Republic of Lithuania. Riflemen’s Union Star Medal. By the act of the Minister of Defense and in the name of the President of the Republic of Lithuania. Dr. Alexander Rackus is awarded the Riflemen’s Union Star Medal. Established in 1939 on the twentieth anniversary of the founding of the Riflemen’s Union. Signed, Brig. General S. Rastikis, Commander-in-Chief of the Army; Signed, Colonel Saladzious, Chief of the Riflemen’s Union Association. Kaunas, 1939, June 24, No. 8367.” Obverse: The emblem of the National Guard, designing by Rimsa, is featured. At the top is depicted a miniature Riflemen’s Union Star, the main order of the Riflemen’s Union. A wreath of oak leaves surrounds the sides, with Rimsa’s “Wise Owl” emblem perched atop an open book.

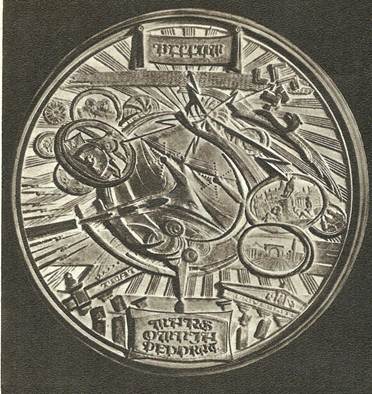

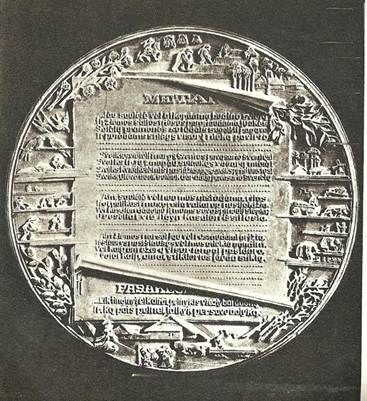

Reverse 12. War and Peace This is the first of Rimsa’s post-World War II medals, designed with the approval of the communist occupational regime in Lithuania. Struck in bronze, this medal measures 34.5 millimeters in diameter. Obverse: Entitled BELLUM (war), this medal shows an intense conflict. The loops of Rimsa’s design contain scenes from major European cities. Bayonets point upward, and a broken swastika appears at the one o’clock position under which is a dead German eagle. In the center a ghost emerges, symbolizing man, the initiator of wars. The lower cartouche bears the inscription MARS OMNIA DEVORAT, which translates “War Destroys Everything.” The “death loops” was an artistic technique that Rimsa had previously used in a bas-relief to depict the ill-fated flight of the Lituanica in 1933, in which various depictions were presented. A 1937 Rimsa exhibition program stated: “There is neither top nor bottom, neither right side nor left, as the view is good from all sides.” This appears to be the case with the obverse of the “War and Peace” medal.

Reverse: Entitled PAX (peace), the dove of peace appears, observing the nation at work in harmony, with a girl trumpeting the victory flag above. Rays of the sun shine brightly in the background. The bottom inscription reads LABOR OMNIA CREAT, which means “Labor Creates Everything.”

Reverse

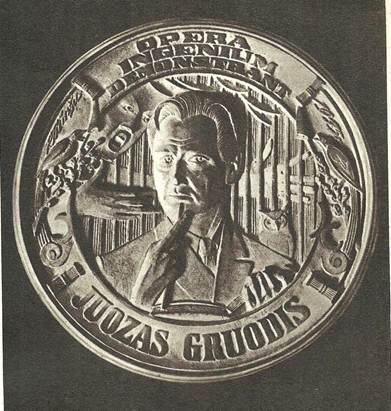

13. In Honor of Juozas Gruodis This medal was struck in bronze in 1945, is a 23.5 millimeters in diameter, and honors the then-living Lithuanian composer, Juozas Groudis. Born in Rakenai on December 20, 1884, Gruodis studies musical composition in Moscow from 1914 to 1916, and in Leipzig from 1920 to 1924. Upon his return from Germany, he became director and professor of composition at the Kaunas School of Music until his death in 1948. Obverse: Featured is the image of Gruodis, with musical and operatic symbols in the background. Included above Gruodis’ left shoulder is Rimsa’s “Wise Owl” emblem. The legend reads OPERA INGENIUM DEMONSTRANT, which translates “his work show ingenuity.” Rimsa’s signature appears in the upper left with the date 1945 opposite. JUOZAS GRUODIS appears under the bust.

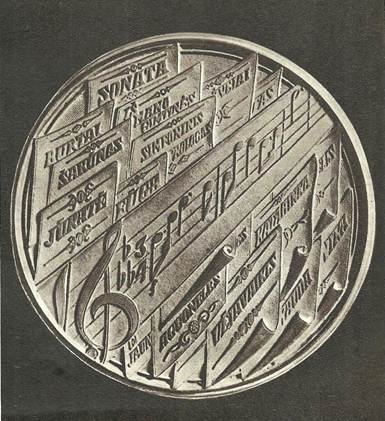

Obverse Reverse: Shown are several titled score sheets of Gruodis’ works.

Reverse

14. First book in the Lithuanian Language Struck in bronze, this 35-millimeter medal commemorates the 400th anniversary of the first Lithuanian language book. The design reflects the communist ideology of post-World War II Lithuania, yet shows Rimsa’s determination for artistic freedom. This is Rimsa’s most well-known medal of the post-War period. Obverse: The design depicts the first Lithuanian language book: a Protestant catechism by Lutheran priest and author Martynas Mazvydas. Apparently the communists permitted Rimsa to reproduce the catechism on his medal for historic documentation and overlooked the religious implications. In the center is the title page of the book, CATECHISMUSA PRASTY SZADEI. This book was originally printed by the Hans Weinreich Press in Koenigsberg, East Prussia (Lithuania Minor), in 1547. The appearance of the book was closely associated with the reform movement. Mazvydas was a well-educated man, and a student at the University of Koenisberg. He encouraged Lithuanians to read and write in their own language. A small bust of Mazvydas appears at the top of the medal. A Lutheran pastor in Ragaine (German: Ragnit, Russian: Neman), Mazvydas was raised to the rank of archdeacon in 1554. He died in 1563. In the background are Lithuanians sitting near a fenced area. The date 1547 appears at the bottom. The Gothic inscription is taken from the first page of the introduction of the catechism, which has become known as the first Lithuanian poem. The famous lines read BRALEI SESERIS IMKIET MANI IR SKAITKIET IR TATAI SKAITIDAMI PERMANIKIET. In modern Lithuanian this reads Broliai, seservys, imkit mane ir skaitykit, which translates “brothers, sisters, take me and read.”

Obverse Reverse: With the University of Vilnius in the background (old observatory building), a professor is shown teaching on a podium with a book below. He is raising his right hand, surrounded by gigantic books, all with corresponding symbols. Represented (left to right) are law, astronomy, architecture, medicine, and technology. Noticeably absent of course, is religion. Displaying the communist hammer and sickle emblem, the podium’s legend reads KURIAME KULTURA TAUTINE FORMA SOCIALISTINE TURINU, which translates “we are creating our country according to the socialistic system.” At the bottom appears the date 1947. Rimsa’s signature appears on the right. The inscription below reads: TEGU SAULE LIETUVOS TAMSUMUS PRASALINA IR SVIESA IR TIESA MUS ZINGSNIUS TELYDI, which means “may the sun of Lithuania banish all darkness, may light and truth guide our steps.”

Reverse

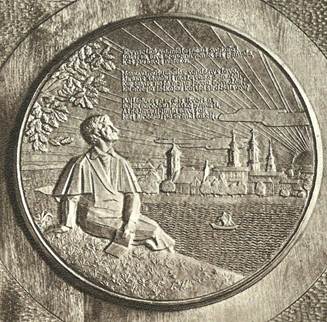

15. Adomas Mickevicius-Rimvydas

This 40-millimeter bronze medal honors the poet Adam Bernard Mickevicius. The medal was begun in 1948 on the 150th anniversary of the poet’s birthday, but was not completed until 1959. Mickevicius was descended from the Lithuanian gentry family Rimvydas. Born in Zaosie on December 25, 1798, Mickevicius received his education at the University of Vilnius. A poet of the traditional classical style, one of his most famous works is a drama entitled Dziady, or “Fore-father’s Eve,” which dealt with the customs of the peasants and their suffering under serfdom. This class struggle theme was encouraged by the communists when they occupied Lithuania in 1940. Mickevicius expressed his deep longing for Lithuania through his writings. 4 He grew up in an ancient Lithuanian city, studied in Vilnius, taught in the heart of the country, considered himself a descendant of the Rimvydas family, counted himself a Lithuanian, and called Lithuania the land of his fathers. Unfortunately, outside of Lithuania Mickevicius was erroneously known as a Polish patriot and writer. He died September 26, 1855, in Constantinople. Obverse: Featured is a bust of Mickevicius with the Cathedral of Vilnius, and the Hill/Tower in the background. This obverse was sculptured by Rimsa in 1948, before communists removed the statues of St. Stanislaus, St. Helen with the Cross, and Lithuanian Patron Saint Casimir from atop the structure (they have since been restored). The legend reads ADOMAS MICKEVICIUS—RIMVYDAS, with the dates 1798-1855 at the bottom. The Vilnius area was familiar to Mickevicius, who, although he is recognized internationally as Polish, spent little of his life in Poland itself. In front of the cathedral stands a Lithuanian girl, clothed in national costume.

Obverse Reverse: Contained are the lines of the poem by Pan Tadeusz, which begins, “Oh, Lithuania, my Fatherland! Thou art like unto health; He only knows thy worth who loses thee.” The city of Kaunas appears in the background, with the Nemunas River flowing by an embankment; the poet sits looking at the city.

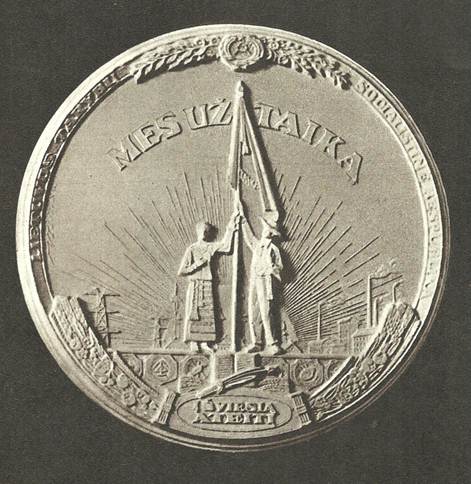

Reverse 16. We are for Peace Obverse: Struck in bronze, this 28-millimeter medal depicts a male and female in native garb with the Lithuanian flag raised, and symbols of industry, architecture, music and art in the background. The title states MES UZ TAIKA, which translates “We are For Peace.” In a small oval at the bottom is the phrase I SVIRSA ATEITI, meaning “into a bright future.” In the top circle appears the communist hammer and sickle emblem. The legend reads LIETUVOS TARYBU SOCIALISTINE RESPUBLIKA, which translates “Lithuanian Soviet Socialistic Republic.”

Obverse

Reverse: Shown is a glorified map of post-World War II Lithuania, containing the names of the country’s major cities: Klaipeda, Siauliai, Panevezys, Kaunas and Vilnius. The date 1949 appears at the bottom. The obverse legend is repeated on this side.

Reverse

17. Kristijonas Donelaitis Struck in bronze, this 36-millimeter medal honors the 175th anniversary of the death of the classical poet. Kristijonas Donelaitis, the first Lithuanian poet to be translated and recognized in histories of European literature. Born January 1, 1714, in Lazdyneliai, Donelaitis studied at the University of Koenigsberg. He was appointed pastor in Tolminkiemis, and in his spare time composed verses in Lithuanian. His most famous work, The Seasons, followed the literacy tendency of the day by portraying the natural setting of the village and its inhabitants rather than cities and/or aristocrats. Donelaitis died on February 18, 1780, in Tolminkiemis, which is now 15 kilometers southwest of the present Lithuanian border. After World War II, the Russians changed the name of the town to Chystye Prudy, and destroyed Donelaitis’ church. Under its ruins were found Donelaitis’ remains. Based upon skull structure, the appearance of the poet has been reconstructed, as Rimsa’s rendering depicts. Obverse: Shown is Donelaitis holding a quill pen, with a library shelf behind him. The inscription reads KRISTIJONAS DONELAITIS 1714-1780. The date 1955 appears at the bottom.

Obverse

Reverse: Depicted is a manuscript of Doneliatis’ most famous work, The Seasons. Consisting of four parts, the medal shows the joys of spring, summer toils, autumn wealth and winter cares. Rimsa features the various seasonal peasant activities aside the manuscript. The poem reveals the class structure that existed during the 18th century.

Reverse

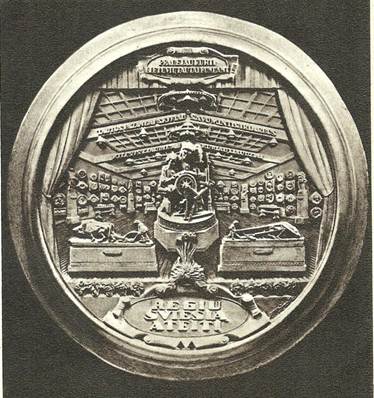

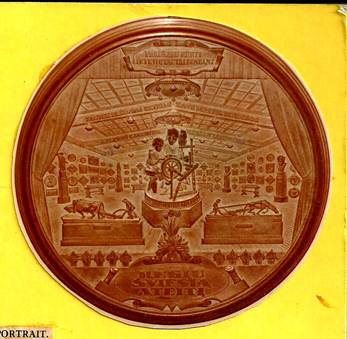

18. Self Portrait A most unusual work and Rimsa’s last medal, this piece was created in the last decade of the sculpture’s life. The obverse was begun in 1950, as Rimsa approaches his 70th birthday. The reverse was completed in 1959. Plaster models, 61 millimeters in diameter, are known to exist, plus one large bronze personal edition. Obverse: The aged sculptor is shown facing forward. The legend reads KUREJA PAZINSITE NE IS VEIDO O IS JO KURYBOS, which translates “the creator will be recognized not by his face, but by his works.” Two versions of the obverse are known. One depicts the artist wearing his favorite wide-brimmed hat, obtained in London in 1924. The other version features a bald-headed portrait of the sculptor.

Obverse

Reverse: Shown is an exhibition of Rimsa’s works, centering around The Lithuanian School and The Ploughman. The walls are filled with medals and plaster models. The legend reads PRADEJAU KURTI LIETUVIU TAUTAI BUNDIANT, which means “I started to work at the time of the awakening of the Lithuanian nation.” At the bottom in an oval cartouche are the words REGIU SVIESIA ATEITI, which translate “I am seeing a bright future.”

Reverse

Acknowledgements

The Balzekas Museum of Lithuanian Culture in Chicago, Illinois, serves as an archival repository for Lithuanian cultural materials. Its numismatic department contains numerous rare Rimsa medals acquired by Dr. Aleksandras M. Rackus. About

the Author

Notes 2. J. Rimantas, Petras Rimsa Pasakoja (Vilnius: Valstybine Grozines Literaturos Leidykla, 1964), pp. 260, 261 3. Jonas K. Karys, Senoves Lietuviu Pinigai (Ancient Lithuanian Money) (Immaculata Press, Bridgeport, Connecticut, 1959), p. 276 4. Encyclopedia Lituanica, 1973 ed. Vol. III (K-M). p. 520 Bibliography Encyclopedia Lituanica. 1973 edition (Vol. III), s.v. “Mickiewicz, Adam Bernard,” by Vincas Maciunas. Ibid. 1975 edition (Vol. IV), “Rimsa, Petras.” Karys, Jonas Kareckas. Senoves Lietuviu Pinigai (Ancient Lithuanian Money). Putnam, Connecticut: Aukselia/Immaculata Press, 1959. Rimantas, J. Petras Rimsa Pasakoja (The Story of Peter Rimsa). Vilnius: Valstybine Groziens Literaturos Leidykla, 1964 Works of Petras Rimsa. Official program for Petras Rimsa’s American shows, January 30 – February 12, 1937. International Institute, Boston, Massachusetts. Zitkus, K., ed. Petras Rimsa. Kaunas: Kauno Valstybinis M. K. Ciurlionio V. Dailes Muziejus, 1966 |

||||||||||||||||

|

|

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

Evaldas Zvinys I believe this is a self-reinforcing circle. The more one talks about the same thing, the more he or she believes in it - and eventually starts acting accordingly. The problem is that the media does not help - oftentimes it is too negative - it focuses too much on the bad and ignores the good. And there definitely are good things - a lot of them. The question is - how to break out of this circle?

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

Nobody needs us there. It is being proven to us every time one of us attempts to come back and be a normal human being

- Posted by - (0) Comment

![]()

Meecolas Goudialis Nobody needs us there. It is being proven to us every time one of us attempts to come back and be a normal human being....It is impossible....

And you can have as many concerts as you want, as many "kulturos sostines" as you want, as many 3 milijonai, Lithuanians come back, Pasaulio Lietuviai, Misija Sibiras projects....it DOES NOT MATTER!!! Unless LT is able to grasp the very heart of the problem. This country is dying....amids all its glory of the "Baltic Tiger", legends of economic stability, best lasers, fastest internet in the world, and all other pr crap....It was sad to see the country enslaved for 50 years, but it is outright shocking to see its soul torn apart in 20!!!!!!!!!!

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

![]()

Bernard Terway You must have had a really bad experience there. I was only there for a short time, so that may be why I enjoyed it so much and would love to go back for an extended period.

Drink a lot of medaus alus when in

Vilnius and Kaunas. It is amazing what a few drinks will do for your mental vision :-) Just being facetious there, but one must look for the good and, if one does, he/she will find it.

- Bookmark :

- Digg