THE VOICE OF INTERNATIONAL LITHUANIA

|

VilNews has its own Google archive! Type a word in the above search box to find any article.

You can also follow us on Facebook. We have two different pages. Click to open and join.

|

Featured black

- Posted by - (0) Comment

Lithuanians

in the World

VilNews will from time to time present Lithuanians who have left the home country and made some kind of career abroad. We are this time not so much looking for celebrity articles, more for some unusual life stories describing Lithuanians who have settled somewhere in the world. Send us your story!From Vilnius University

to modeling in Milan

Giedrė Jotautaitė, Milan, Italy

I'm from Vilnius, born and raised here. I finished school in Vilnius and afterwards I studied Business Information Management at the University of Vilnius. Two years ago, the university required us to have practice from a business, and as I have always wanted to travel more, I decided to practice outside Lithuania. I had a friend in Italy who helped me to find a company where I could do this. So I filled in all the papers and participated in an Erasmus practice competition, and won! Afterwards I came to live in Milan. I chose Italy for many reasons: Milan has always been the centre of fashion, attracting many people from all over the world. I love Italian climate, food, their basic outlook on life and ability to do less than what is needed and not be punished. Italy has everything – mountains, sea, culture and architecture, beautiful history ... They have very good taste for living, which includes everything: from clothes to where to go on vacation.

When I participated in the Erasmus programme I fell in love with an Italian guy, at first I thought it would be just a game, but after that it became a really beautiful, lasting thing.

I came back to Lithuania after Erasmus to pass exams in Vilnius University and after I finished I thought I would go back to Italy just for the summer, but time goes very fast and I'm still here…

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - (0) Comment

Has the spirit of

January 1991 returned?

Is there a new Lithuanian awakening in the making?

What do you, dear reader, think?

By Aage Myhre, editor-in-chief

aage.myhre@VilNews.com

The 22 years that have passed since January 1991, when the Lithuanian people in an exemplary, peaceful manner stood up against the violent Soviet re-occupation, have only rarely lived up to the expectations I and many with me had by then.

Neither Landsbergis, Brazauskas, nor later leaders delivered when the new statehood was to be developed during the 1990s.

The country's newfound freedom did not lead to the type of growth and better living conditions for the broad masses, that had been expected. Also, the warmer, friendlier and more human society we all waited for never occurred. When the people who had shown their support for the new won independence from the Soviet Union returned to their towns and villages in the spring of 1991, much of the community spirit was gone and did not appear since.

Different leaders have since those days made some half-hearted attempts to regain team feeling, cooperation and community spirit within groups of the Lithuanian people. These attempts have largely been met with shrug and distrust, and few politicians have gained genuine respect of their own people.

The EU membership in 2004 did not become the boost that had been expected. Certainly, the economy enjoyed a positive step forward, but not much positive happened for the broad masses of the people.

Therefore, the most striking result of the membership and the open borders to the West, was a mass exodus unparalleled in and for any other country of today.

The enormous crisis that began in 2008 made the situation even worse, almost unbearable for many, and one felt that it was only a matter of time before the country would collapse, emptied of inhabitants.

Then, a year or two ago, I felt that something was happening down in the grassroots of business people and others. I discovered more and more young professionals who began to define their own paths, no longer waiting for the older generations of leaders to show the way.

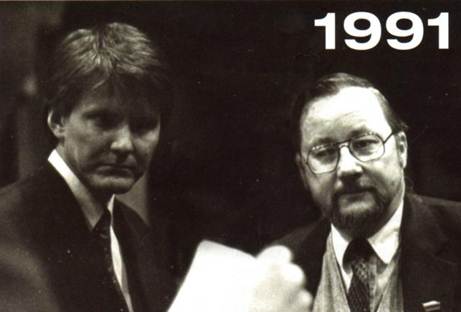

When I this year marked 13 January in the Lithuanian Parliament Building, 22 years after I in 1991 stood there with Professor Landsbergis looking out the window at the bonfires, barricades and the huge crowd of unarmed people who had gathered to protect their president and the country's future as a free nation, I saw something completely new to me…

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - (0) Comment

Has the spirit of

January 1991 returned?

Is there a new Lithuanian awakening in the making?

What do you, dear reader, think?

By Aage Myhre, editor-in-chief

aage.myhre@VilNews.com

The 22 years that have passed since January 1991, when the Lithuanian people in an exemplary, peaceful manner stood up against the violent Soviet re-occupation, have only rarely lived up to the expectations I and many with me had by then.

Neither Landsbergis, Brazauskas, nor later leaders delivered when the new statehood was to be developed during the 1990s.

The country's newfound freedom did not lead to the type of growth and better living conditions for the broad masses, that had been expected. Also, the warmer, friendlier and more human society we all waited for never occurred. When the people who had shown their support for the new won independence from the Soviet Union returned to their towns and villages in the spring of 1991, much of the community spirit was gone and did not appear since.

Different leaders have since those days made some half-hearted attempts to regain team feeling, cooperation and community spirit within groups of the Lithuanian people. These attempts have largely been met with shrug and distrust, and few politicians have gained genuine respect of their own people.

The EU membership in 2004 did not become the boost that had been expected. Certainly, the economy enjoyed a positive step forward, but not much positive happened for the broad masses of the people.

Therefore, the most striking result of the membership and the open borders to the West, was a mass exodus unparalleled in and for any other country of today.

The enormous crisis that began in 2008 made the situation even worse, almost unbearable for many, and one felt that it was only a matter of time before the country would collapse, emptied of inhabitants.

Then, a year or two ago, I felt that something was happening down in the grassroots of business people and others. I discovered more and more young professionals who began to define their own paths, no longer waiting for the older generations of leaders to show the way.

When I this year marked 13 January in the Lithuanian Parliament Building, 22 years after I in 1991 stood there with Professor Landsbergis looking out the window at the bonfires, barricades and the huge crowd of unarmed people who had gathered to protect their president and the country's future as a free nation, I saw something completely new to me.

I was, now in 2013, there with a group of young Lithuanians, most of them so young that they do not have their own memories of what happened there 22 years ago. Yet the memories of the sad events in January 1991 were obviously alive and present for them. They wanted to underline that freedom and independence is not something one can take for granted. I was there with some of Lithuania's future politicians – young, well-educated, smart leaders that this country a few years ago could only dream about.

I walked around with them in the Parliament this 13th January. I saw their interests, and their pride in belonging to a great nation like this.

I also saw large photographs on the walls, with Lithuania's parliamentary history of the interwar time and from the years after the Declaration of Independence 11 March 1990. The sadness I felt when I walked around in these corridors 22 years was gone, now I felt only joy, and optimism regarding the country's future and its political leaders for the years to soon come.

I had, before this visit, seen young Lithuanian business people in full swing building up more professional structures and attitudes. That I now saw the same happen among young politicians was very gratifying.

Both of these groups feel to some extent that our brand new government is a step backwards, back to the "nomenclature times", but their young, Western-type way of thinking is certainly very encouraging and I think we are facing a crossroads which bodes well for Lithuania!

It is precisely such attitudes I now see more and more of among young Lithuanians. And this time, it appears that they are ready to take matters into their own hands, no longer waiting for the older politicians and leaders to show the way. It almost feels as if the spirit of January 1991 is back, now in a structured, pragmatic and professional manner.

What do you, dear reader, think? Is there a new awakening in the making? Has the spirit of 1991 returned?

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - (0) Comment

|

Commemorating January 1991

|

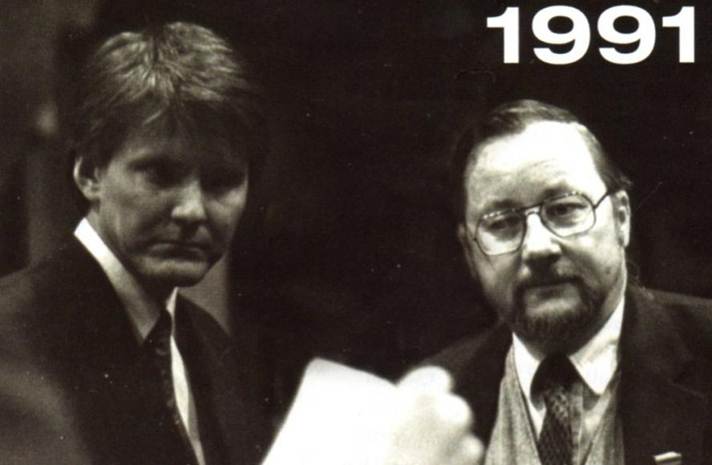

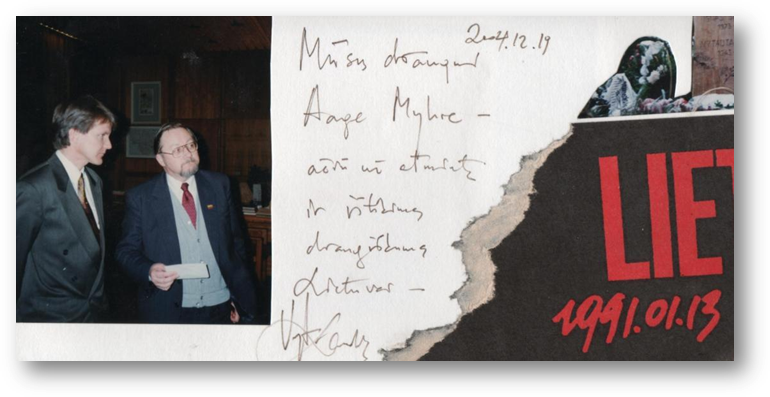

21 January 1991: Soviet military vehicles dominated the streets of Vilnius. Dag Andersen and I presented a letter from Oslo Municipality, signed by Mayor Michael Tetzschner. Oslo offered Vilnius to become its first friendship city in the West. The letter was enthusiastically received by the Vilnius Mayor Arunas Grumadas and Deputy Mayor Regimantas Ciupaila.

Photo: Aftenposten, Norway.

Aage Myhre, VilNews Editor-in-Chief

aage.myhre@VilNews.com

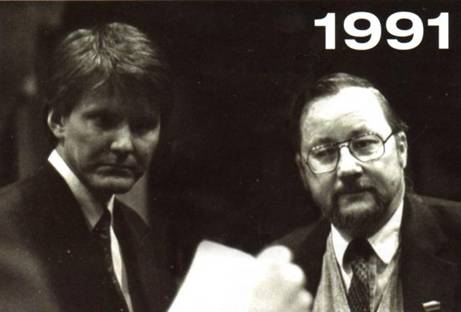

We were two Norwegians working very much with Lithuanian affairs during autumn/winter of 1990-91, Dag Andersen and me. During our visit to Vilnius in January 1991, we showed our respect to President Vytautas Landsbergis in his Parliament office and worked with journalists to spread the message about the Soviet assault to the world.

We also brought with us a letter from the City Council Leader of Oslo, Michael Tetzschner inviting the Mayor of Vilnius to sign a sister city agreement. We handed the letter over to Mayor Arunas Grumadas on 21 January while Soviet troops were standing around in the streets and armoured vehicles roared around us.

The twin city agreement was signed a few months later, and Oslo became thus the first Western city to enter into such an agreement with Vilnius. I saw it as an important symbol of friendship and solidarity at a difficult time for a country under tremendous pressure and terrible abuse from Lithuania’s power loving neighbour to the east.

We came via Riga

We were a small group of Norwegians who travelled from Oslo to Vilnius a few days after the infamous Soviet attack and its killings on the 13th of January 1991. It was originally planned as a larger delegation, with parliamentarians, but they had to postpone their trip due to the death of our Norwegian King Olav.

We came to Vilnius via Copenhagen and Riga, whereto Scandinavian Airlines as the first western airline had established a route a few months earlier. Travel insurance cover was 400% higher than normal. The Baltic States were now defined as a war zone.

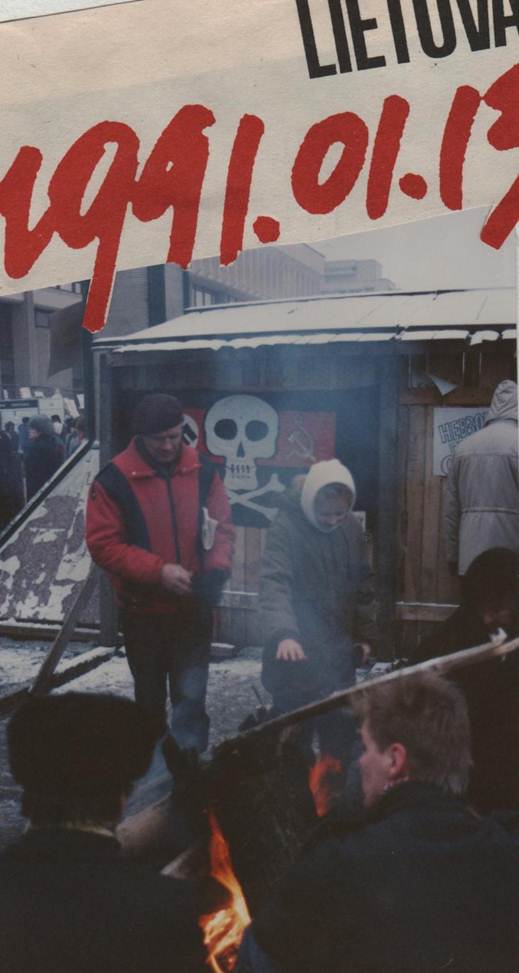

In Riga we first visited the Radio and Television House. The smoke from the many bonfires around the building lay like a blanket over the area, with a penetrating but good smell of firewood. It was an impressive sight to see the thousands of Latvians who camped around the territory in tents and primitive shelters to protect the freedom of peaceful broadcast against the Soviet perpetrators.

We, our Norwegian team, together with journalists travelled to Latvia and Lithuania as soon as we could after the Soviet attack in January 1991. The Balts refused to accept the Soviet invasion. They did their utmost to protect their governments and media. Here we are with 'activists' in Riga. For several weeks they made bonfires, staying here in tents night after night to demonstrate against the new Soviet assault.

Photo: Aage Myhre, January 1991.

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - (2) Comment

|

Commemorating January 1991

|

21 January 1991: Soviet military vehicles dominated the streets of Vilnius. Dag Andersen and I presented a letter from Oslo Municipality, signed by Mayor Michael Tetzschner. Oslo offered Vilnius to become its first friendship city in the West. The letter was enthusiastically received by the Vilnius Mayor Arunas Grumadas and Deputy Mayor

Regimantas Ciupaila. Photo: Aftenposten, Norway.

Aage Myhre, VilNews Editor-in-Chief

aage.myhre@VilNews.com

We were two Norwegians working very much with Lithuanian affairs during autumn/winter of 1990-91, Dag Andersen and me. During our visit to Vilnius in January 1991, we showed our respect to President Vytautas Landsbergis in his Parliament office and worked with journalists to spread the message about the Soviet assault to the world.

We also brought with us a letter from the City Council Leader of Oslo, Michael Tetzschner inviting the Mayor of Vilnius to sign a sister city agreement. We handed the letter over to Mayor Arunas Grumadas on 21 January while Soviet troops were standing around in the streets and armoured vehicles roared around us.

The twin city agreement was signed a few months later, and Oslo became thus the first Western city to enter into such an agreement with Vilnius. I saw it as an important symbol of friendship and solidarity at a difficult time for a country under tremendous pressure and terrible abuse from Lithuania’s power loving neighbour to the east.

|

OSLO

The Oslo coat of arms is almost 700 years old. It shows the patron saint, of Oslo, St. Hallvard, sitting on a throne decorated with two lions' heads with a halo around his head. In front of the throne lies the woman whom he tried to protect. In one hand he holds the three arrows which killed both him and the woman. |

VILNIUS

In pagan times, until the end of the 14th century, the Vilnius coat of arms featured Titan Alkis, hero of Lithuanian ancient tales, carrying his wife Janteryte on his shoulders across the river.

|

During 1991 I came back to Lithuania several times. I saw more, understood more. The country began in earnest to fascinate me. I was also in Vilnius during the failed coup in Moscow in August 1991, again thrilling days. On the morning of 30 August 1991 I was probably the first person in modern times who got a Lithuanian visa that was legally accepted internationally, stamped into my Norwegian passport. Early morning the 30th of August 1991, the day when the Lithuanian migration authorities finally could do so in accordance with international rules.

The Soviet Union was finally a horror of the past. Also formally, Lithuania was once again a free and independent country. 50 years of abuse and oppression was over!

Vilnius images, winter 1990-91

|

|

Heavy tanks were used by the Soviet forces when they attacked the TV tower and the Parliament building in Vilnius on 13 January 1991 (left). They were met by a wall of unarmed people who refused to allow the intruders to again take control of their homeland. Inside the city they used armoured vehicles on rubber wheels (below). It was a bizarre, almost surreal experience to always hear the noise, feel the ground tremble when we were in meetings or trying to get a meal in one of the city's few restaurants. |

|

|

|

We often did our eating and drinking in Hotel Lietuva, in the so-called 'Black Bar', where only western, hard currencies were accepted. This bar was the centre for international media those January days. Every night we heard stories about how television crews and journalists had experienced rather harsh confrontations with the Soviet military units. |

|

||

Windows all over Vilnius were taped like this those

January days, in order not to break when the heavy

Soviet vehicles passed by.

|

|

|

|

|

ABOVE: During my first visit to Lithuania, in November 1990, I took this picture at Rotušes Square (Town Hall Square) in Vilnius. This was probably the very last picture ever made of the statue of Vincas Mickevičius-Kapsukas here. Next morning he had been knocked down by local activists... After the WWII Soviet occupation of Lithuania, his student Antanas Sniečkus (see our article https://vilnews.com/?p=6598) propagated Mickevičius' personality cult. In his honour the city of Marijampolė was renamed Kapsukas (1956–1989) and Vilnius University (1955–1990) bore his name. Two large sculptures of Mickevičius were erected in Vilnius: one here, in front of the Vilnius Town Hall (1962) and another, depicting Mickevičius with Lenin, in Antakalnis (1979). LEFT: You can today find the statue of Mickevičius-Kapsukas in the Grutas Park in Southern Lithuania. The park is the repository of old Soviet era statues and artefacts that were removed from public places when Soviet occupation of Lithuania ended.

|

Delivery of coal to properties in Pilies g. right in the centre of Vilnius, with horses, 22 years ago.

People picked the coal up in burlap sacks. Other times the horse driver was simply shovelling

the coal out on the sidewalk in front of the buildings on his ordering list.

Photo: Aage Myhre.

One of the few shop windows in Vilnius in 1990-91.

Photo: Aage Myhre.

We came via Riga

We were a small group of Norwegians who travelled from Oslo to Vilnius a few days after the infamous Soviet attack and its killings on the 13th of January 1991. It was originally planned as a larger delegation, with parliamentarians, but they had to postpone their trip due to the death of our Norwegian King Olav.

We came to Vilnius via Copenhagen and Riga, whereto Scandinavian Airlines as the first western airline had established a route a few months earlier. Travel insurance cover was 400% higher than normal. The Baltic States were now defined as a war zone.

In Riga we first visited the Radio and Television House. The smoke from the many bonfires around the building lay like a blanket over the area, with a penetrating but good smell of firewood. It was an impressive sight to see the thousands of Latvians who camped around the territory in tents and primitive shelters to protect the freedom of peaceful broadcast against the Soviet perpetrators.

Inside Riga's Old Town there were equally many bonfires and barricades, especially around the Latvian parliament building. Our delegation was given entrance passes, and that night we stood inside the building to show our support and talking to MPs and others who stayed there, many of them around the clock.

In the evening we experienced a rather startling example of the Soviet propaganda machinery when there on the TV news from Moscow was informed that Soviet soldiers had just moved in and taken control of the Parliament and Riga city. Not a single soldier was to see, neither inside nor outside the building, but this was a stunning reminder of how disinformation and propaganda are important parts of any war or conflict.

It was dangerous to embark on the road those days, but the Latvian Customs agreed to drive us, in their red jeeps, to the Lithuanian border next morning. On the Lithuanian side of the border, which still was not established with checkpoints, we were picked up by Lithuanian Lada cars, and not long after we were on the way to Vilnius. We passed convoys of Soviet military vehicles, but arrived without being stopped or subjected to interrogation of any kind.

Our main mission of the trip began…

We, our Norwegian team, together with journalists travelled to Latvia and Lithuania as soon as we could after the Soviet attack in January 1991. The Balts refused to accept the Soviet invasion. They did their utmost to protect their governments and media. Here we are with 'activists' in Riga. For several weeks they made bonfires, staying here in tents night after night to demonstrate against the new Soviet assault.

Photo: Aage Myhre, January 1991.

Without the intense media coverage that took place in January 1991, the outcome could well have become different. The Soviet occupiers could have re-taken control of the Baltic States. Here a journalist from Norwegian Aftenposten interviewing the leader of the Latvian border guards. The international press made a huge effort to make the world know about the Soviet atrocities.

Photo: Aage Myhre, January 1991.

Lithuania – Norway, a strong alliance also today!

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - (0) Comment

Visit to the Lithuanian

Parliament (Seimas)

22 years later

Lithuanian Foreign Ministry issued primitive passes for us,

and we managed to get through a long maze of controls,

barbed wire, concrete blocks and barricades that surrounded

the Lithuanian Parliament those January days in 1991. We got

the opportunity to visit this brave Parliament President,

Professor Vytautas Landsbergis, in his office. Here he

lived day and night for weeks while the Soviets

surrounded the building with troops and tanks.

Text and photos: Aage Myhre, Editor-in-Chief

aage.myhre@VilNews.com

This year I marked 13 January in the Lithuanian Parliament Building, 22 years after I in 1991 stood here in this building, along with Professor Landsbergis and looked out the window at the bonfires, barricades and the huge crowd of unarmed people who had gathered to protect their president and the country's future as a free nation.

I came here today with a group of young Lithuanians, most of them so young that they do not have their own memories of what happened here 22 years ago. Yet the memories of the sad events in January 1991 are very much alive and present for them. They want to remember that freedom and independence is not something you can take for granted, and they want to pursue a political career. They are Lithuania's future politicians. They are the future of young, well-educated, smart leaders that this country a few years ago could only dream about.

I walked around with them in the Parliament this 13th January. I saw their interests, and their pride in belonging to a great nation like this.

I also saw large photographs on the walls, with Lithuania's parliamentary history of the interwar time and from the years after the Declaration of Independence 11 March 1990. The sadness I felt when I walked around in these corridors 22 years was gone, now I felt only joy, and optimism regarding the country's future and its political leaders for the years to soon come.

Entrance to the old part of the Parliament.

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - (1) Comment

Visit to the Lithuanian

Parliament (Seimas)

22 years later

Lithuanian Foreign Ministry issued primitive passes for us,

and we managed to get through a long maze of controls,

barbed wire, concrete blocks and barricades that surrounded

the Lithuanian Parliament those January days in 1991. We got

the opportunity to visit this brave Parliament President,

Professor Vytautas Landsbergis, in his office. Here he

lived day and night for weeks while the Soviets

surrounded the building with troops and tanks.

Text and photos: Aage Myhre, Editor-in-Chief

aage.myhre@VilNews.com

This year I marked 13 January in the Lithuanian Parliament Building, 22 years after I in 1991 stood here in this building, along with Professor Landsbergis and looked out the window at the bonfires, barricades and the huge crowd of unarmed people who had gathered to protect their president and the country's future as a free nation.

I came here today with a group of young Lithuanians, most of them so young that they do not have their own memories of what happened here 22 years ago. Yet the memories of the sad events in January 1991 are very much alive and present for them. They want to remember that freedom and independence is not something you can take for granted, and they want to pursue a political career. They are Lithuania's future politicians. They are the future of young, well-educated, smart leaders that this country a few years ago could only dream about.

I walked around with them in the Parliament this 13th January. I saw their interests, and their pride in belonging to a great nation like this.

I also saw large photographs on the walls, with Lithuania's parliamentary history of the interwar time and from the years after the Declaration of Independence 11 March 1990. The sadness I felt when I walked around in these corridors 22 years was gone, now I felt only joy, and optimism regarding the country's future and its political leaders for the years to soon come.

Entrance to the old part of the Parliament.

HISTORY OF TODAY’S PARLIAMENT BUILDING (SEIMAS)

The construction of the new Seimas building began in April 1976, on the site of a former stadium. By then, the Parliament was still directly depended on the Communist Party. The legal acts passed by the Supreme Council of the USSR was just a “decoration” of the Soviet order. Selected by sex, nationality, education, professions, membership in Communist or Young Communist organisations, the local trade union, so-called deputies used to convene two or three times per year and voted on the draft legal acts already submitted. Undoubtedly, this was an imitation of government, a spectacle. Indeed, the main lobby could remind one of a theatre.

Today’s democratic parliamentarian system got its first test on 11 March 1990, when the Lithuanian Supreme Soviet elected Vytautas Landsbergis president and formally declared Lithuania to be an independent nation. The Soviet President M. Gorbachev rejected the action, insisting that a separation had to be negotiated. In April same year he ordered an economic blockade of Lithuania, cutting off all oil supplies and reducing natural gas flow to one-quarter of the normal level. The blockade ended on 30 June after the Lithuanian Parliament voted to freeze the declaration of independence for 100 days in order to permit negotiations between Moscow and Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania.

Then came 13 January 1991. That was the day when Soviet troops cracked down in Vilnius and the resulting bloodshed made headlines around the world. The action was apparently a bid to stop Lithuania’s independence drive in its tracks. But President Landsbergis and other political leaders wanted it all very differently, making the Parliament building a fortress for democracy and freedom those winter days, with thousands and thousands of unarmed Lithuanians surrounding the building and thereby stopping the Soviet troops from attacking.

ABOVE: The Lithuanian Parliament building as it looks today.

BELOW: Pictures on the Parliament walls, describing Lithuania’s parliamentarian events in 1990-1991.

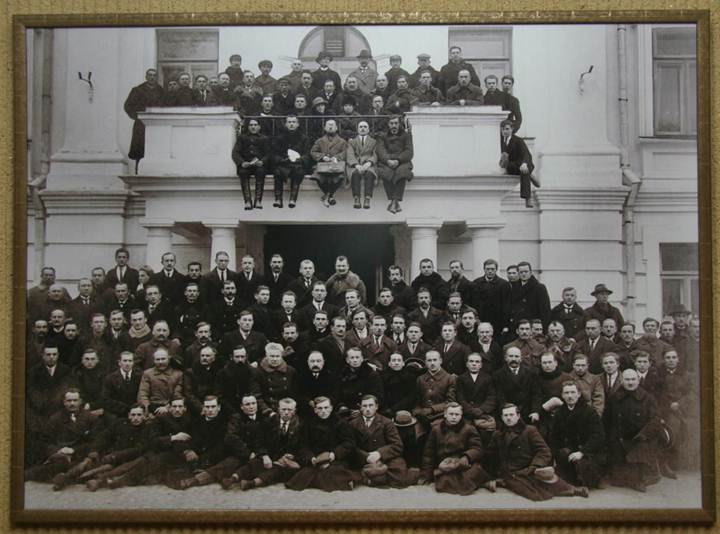

ABOVE: Seimas, 11 March 1990, the day Lithuania re-claimed its independence.

BELOW: The same Parliament Hall today.

Today’s top modern Parliament Hall.

|

|

On the 11th of March 1990 the Lithuanian Supreme Council (today’s Parliament) decided to change the Soviet Coat of Arms hanging behind the chair of the parliament president (above), to Vytis, the symbol of genuine Lithuania (left). The coat of arms of Lithuania, consists of an armour-clad knight on horseback holding an olden sword and shield, also known as Vytis ("the Chaser"). The Lithuanian coat of arms is one of the oldest national coats of arms in Europe. It is one of very few containing symbolism adopted from ducal portrait seals rather than from coats of arms of dynasties, which is the case for most European countries.

|

ABOVE: Barricades and bonfires outside the Parliament in January 1991.

BELOW: This is what is left of the barricades today, covered by a modern glass structure.

BELOW: The Parliament’s entrance hall on 13 January 2013, filled with activities in memory of 13 January 1991.

80 year old Liuda Komarovskaja lost her health by defending the Vilnius TV Tower in the 13 January 1991 events.

She was beaten unconscious by the Soviet soldiers and rushed to the Santariškių Hospital in the outskirts of Vilnius. Here in conversation with Parliamentarian Petras Austrevicius in the Parliament last Sunday.

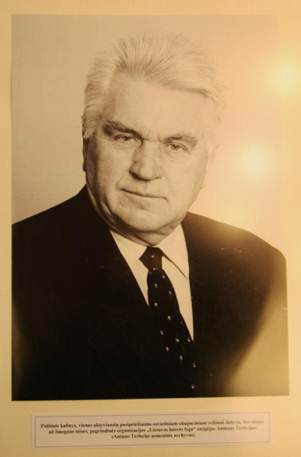

ABOVE: Antanas Terleckas, founder and leader of the Lithuanian Freedom League, was awarded the 2012 Freedom Prize at a solemn event at the Lithuanian Parliament on Sunday 13 January. Read more at http://www.15min.lt/en/article/culture-society/freedom-prize-awarded-to-lithuanian-freedom-league-leader-antanas-terleckas-528-296400

BELOW: A special exhibition about Antanas Terleckas’ life was presented in the Parliament during the13 January commemoration days.

BELOW: Pictures on the Parliament walls, from interwar sessions.

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - (0) Comment

The bonfires and

The bonfires and

barricades that

saved Lithuania

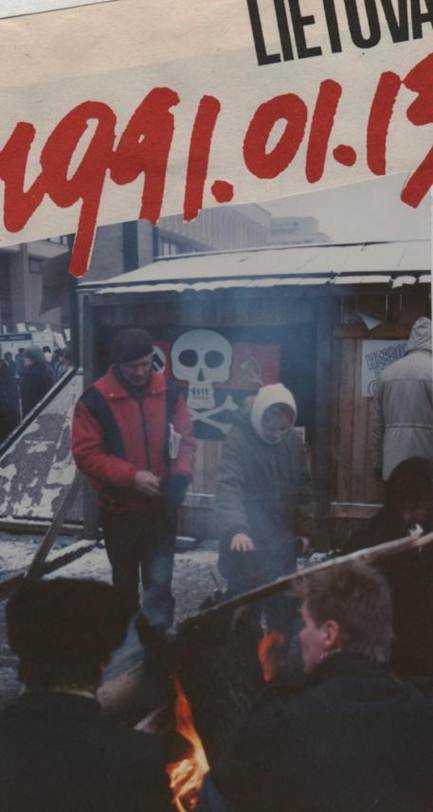

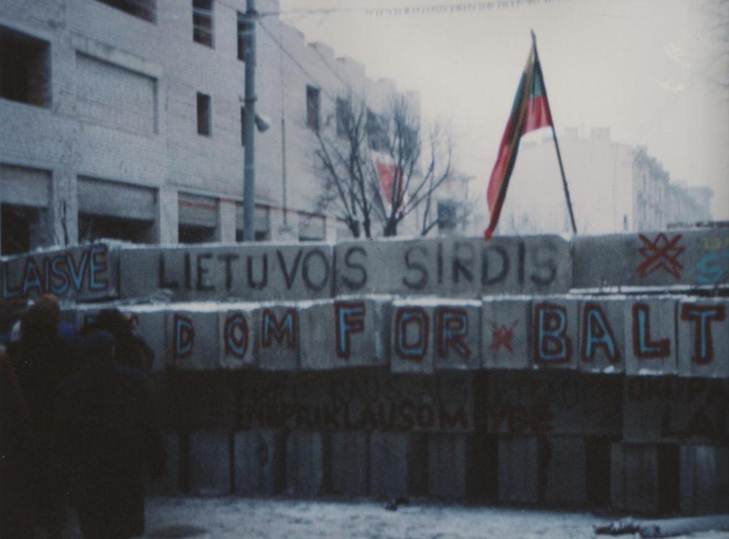

In January 1991, the Lithuanian Parliament was for weeks surrounded by hordes of people, bonfires, concrete blocks and vehicles that the Lithuanian people had brought there to protect their leader and their elected representatives against the Soviet atrocities against innocent

people. Today, exactly 22 years later, the Parliament is

surrounded by peaceful, quiet winter streets.

Top photo: Zenono Nekrošiaus

Text and photos: Aage Myhre, Editor-in-Chief

aage.myhre@VilNews.com

It was not bonfires, concrete blocks, steel beams, barbed wire or tractors which in themselves rescued Lithuania in January 1991. But it was these simple remedies, not weapons, that came to represent the peaceful resistance Lithuanians showed towards their powerful opponent from the east.

I'll never forget the sight of the flames and the large crowd that met me the day I was walking down the Gedimino prospekto towards the Parliament an icy winter day in January 1991. I read a combination of hope and despair in the faces, but first of all I saw determination. This time we will not surrender! The Soviet Union shall not again be allowed to trample us down under its iron heel!

The tactics succeeded. The Lithuanian people united as never before, or since, and the assailants had to withdraw in favour of a free and democratic Lithuania. Some of the symbols of this defining moment in our country's history can still be seen outside the Parliament.

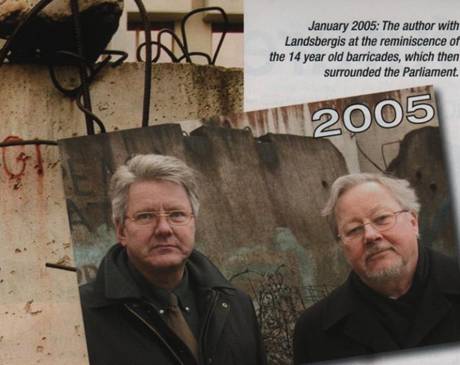

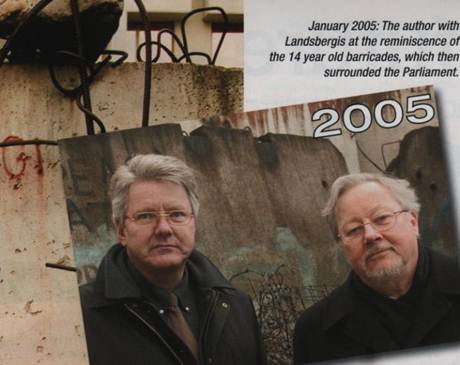

In January 1991 I crossed the barricades to visit President Vytautas Landsbergis in his Lithuanian Parliament office, while the Soviet troops and tanks continued to surround the building. 14 years later we visited together what was left of the concrete barricades from that time. These are now protected by a glass structure.

1991

2013

1991

2013

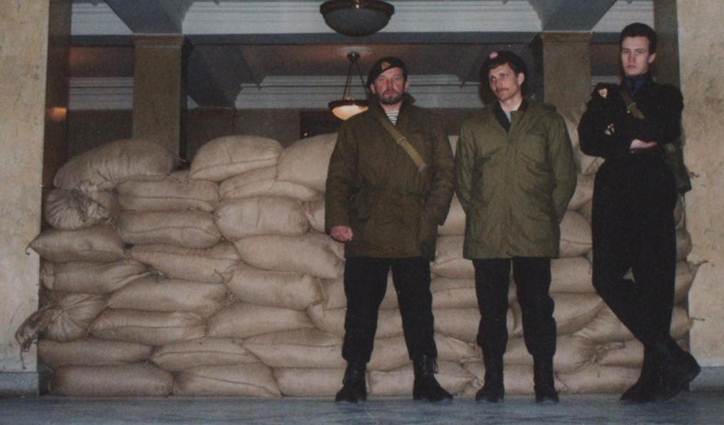

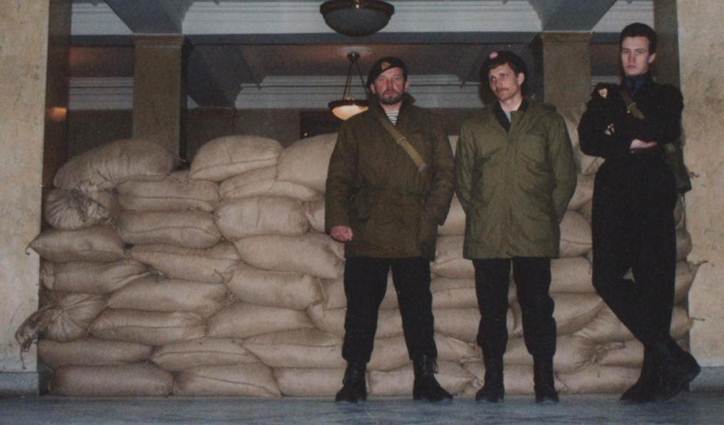

It was very touching to see how the Balts acted to keep their newfound freedom and protect their home country during the very difficult January days of 1991. Here, at the entrance to the Lithuanian Foreign Ministry, the young men have put on homemade clothes that are meant to look like uniforms. They carry rifles and other weapons they have found in their homes. Sand bags have an important symbolic effect. Brave guys!

Photo: Aage Myhre, 18 January 1991.

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - (0) Comment

The bonfires and

The bonfires and barricades that

saved Lithuania

In

January 1991, the Lithuanian Parliament was for weeks surrounded by hordes of people,

bonfires, concrete blocks and vehicles that the Lithuanian people had brought

there to protect their leader and their elected representatives against the

Soviet atrocities against innocent people. Today, exactly 22 years later,

the

Parliament is surrounded by peaceful, quiet winter streets.

Top

photo: Zenono Nekrošiaus

Text

and photos: Aage Myhre, Editor-in-Chief

aage.myhre@VilNews.com

It was not bonfires, concrete blocks, steel beams, barbed wire or tractors which in themselves rescued Lithuania in January 1991. But it was these simple remedies, not weapons, that came to represent the peaceful resistance Lithuanians showed towards their powerful opponent from the east.

I'll never forget the sight of the flames and the large crowd that met me the day I was walking down the Gedimino prospekto towards the Parliament an icy winter day in January 1991. I read a combination of hope and despair in the faces, but first of all I saw determination. This time we will not surrender! The Soviet Union shall not again be allowed to trample us down under its iron heel!

The tactics succeeded. The Lithuanian people united as never before, or since, and the assailants had to withdraw in favour of a free and democratic Lithuania. Some of the symbols of this defining moment in our country's history can still be seen outside the Parliament.

In

January 1991 I crossed the barricades to visit President Vytautas Landsbergis

in

his Lithuanian Parliament office, while the Soviet troops and tanks continued

to

surround the building. 14 years later we visited together what was left of the

concrete

barricades from that time. These are now protected by a glass structure.

1991

2013

1991

2013

It

was very touching to see how the Balts acted to keep their newfound freedom and

protect their home country during the very difficult January days of 1991. Here, at the entrance to the Lithuanian Foreign Ministry,

the young men have put on homemade clothes that are meant to look like

uniforms. They carry rifles and other

weapons they have found in their homes. Sand

bags have an important symbolic effect. Brave guys!

Photo:

Aage Myhre, 18 January 1991.

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - (0) Comment

If there were those in the West who had not heard of Lithuania before, they almost certainly had by the end of the day

13 January 1991

Heavy tanks were used by the Soviet forces when they attacked the Vilnius TV tower and the Parliament building on 13 January 1991. They were met by a wall of unarmed people who refused to allow the intruders to again take control of their homeland.

Text: Aage Myhre, editor-in-chief

aage.myhre@VilNews.com

"Lithuanians, do not resist, your government has betrayed you. Go home to your families and children."

This was the repeated announcement from the Soviet military vehicles with loudspeakers on the roofs, so-called sound trucks that rolled through the streets of Vilnius in January 1991. But fortunately for Lithuania and the United Europe that we now take more or less for granted, there was a music professor and a complete small nation that wanted it all differently.

Had it not been for this peaceful struggle of recovered freedom against an invasion and occupation, the people of the Baltic States never wanted or agreed to, the map of Europe would most likely have looked quite different today.

If there were those in the West who had not heard of Lithuania before, they almost certainly had by the end of the day 13 January 1991. It was the day that Soviet troops struck in Vilnius. The bloodshed that followed made headlines around the world. The attack was apparently an attempt to stop the Lithuanian independence movement in its very beginning.

When the smoke of the Soviet weapons ceased, more than a dozen people had been killed, hundreds injured. Soviet’s attack, and especially the killings at the TV tower, brought not only fame and sympathy for Lithuania from around the world, it was also a defining moment for the Lithuanians themselves.

The bloodshed meant that a point of no return had been crossed. If there was someone who until now had believed that a peaceful settlement with Moscow was possible, it was now clear to everyone that such a thing was unthinkable.

VIDEO FROM 13 JANUARY 1991

The 1991 January events took place in Lithuania between January 11 and 13, in the aftermath of the Act of the re-establishment of the State of Lithuania. As a result of Soviet military actions, 14 civilians were killed and more than 1000 injured. The events were centered in Vilnius, along with related actions in the cities of Alytus, Šiauliai, Varėna, and Kaunas.

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - (6) Comment

If there were those in the West who had not heard of Lithuania before, they almost certainly had by the end of the day 13 January 1991

Heavy tanks were used by the Soviet forces when they attacked the Vilnius TV tower and the Parliament building on 13 January 1991. They were met by a wall of unarmed people who refused to allow the intruders to again take control of their homeland.

Text: Aage Myhre, editor-in-chief

aage.myhre@VilNews.com

"Lithuanians, do not resist, your government has betrayed you. Go home to your families and children."

This was the repeated announcement from the Soviet military vehicles with loudspeakers on the roofs, so-called sound trucks that rolled through the streets of Vilnius in January 1991. But fortunately for Lithuania and the United Europe that we now take more or less for granted, there was a music professor and a complete small nation that wanted it all differently.

Had it not been for this peaceful struggle of recovered freedom against an invasion and occupation, the people of the Baltic States never wanted or agreed to, the map of Europe would most likely have looked quite different today.

If there were those in the West who had not heard of Lithuania before, they almost certainly had by the end of the day 13 January 1991. It was the day that Soviet troops struck in Vilnius. The bloodshed that followed made headlines around the world. The attack was apparently an attempt to stop the Lithuanian independence movement in its very beginning.

When the smoke of the Soviet weapons ceased, more than a dozen people had been killed, hundreds injured. Soviet’s attack, and especially the killings at the TV tower, brought not only fame and sympathy for Lithuania from around the world, it was also a defining moment for the Lithuanians themselves.

The bloodshed meant that a point of no return had been crossed. If there was someone who until now had believed that a peaceful settlement with Moscow was possible, it was now clear to everyone that such a thing was unthinkable.

The 1991 January events took place in Lithuania between January 11 and 13, in the aftermath of the Act of the re-establishment of the State of Lithuania. As a result of Soviet military actions, 14 civilians were killed and more than 1000 injured. The events were centered in Vilnius, along with related actions in the cities of Alytus, Šiauliai, Varėna, and Kaunas.

Professor Vytautas Landsbergis was the central actor in the drama that took place . The colourful, sometimes tempered music professor who was elected Lithuania's president (chairman of the parliament) in March 1990, and from then on become the symbol of the Lithuanian liberation movement. Before the attack in January 1991, his constant talks about breaking free from the Soviet Union, and Lithuania's moral right to do just that, alarmed observers in the West almost as much as in the Kremlin. When the rage was taken completely out of hand in January 1991, Gorbachev seemed as if he did not understand what was happening right in front of him.

Our little Norwegian delegation met with Landsbergis in the parliament on the 19th of January 1991. He lived there, entrenched, protected by his own people. Tens of thousands were ‘camping’ outside the building, inside homemade barricades of concrete blocks and barbed wire. Trucks and tractors were also part of the barricades. In a circle further out stood the Soviet forces, ready to attack when the command word would be given. Fortunately it didn’t happen. The pressure had become strong from all around the world.

We got through the barricades. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs had provided us with appropriate admission papers. It was a moving encounter with a brave man we experienced inside. The little stroke that fell the huge oak. World history was created there and then. In front of our eyes. We were the eye witnesses.

The editor with President Vytautas Landsbergis in the Lithuanian Parliament (Seimas), while the

Soviet troops and tanks continued to surround the building in January 1991.

Bonfires, day and night, outside the Parliament, January 1991.

Photo: Aage Myhre.

Bonfires outside the Parliament, January 1991.

Photo: Aage Myhre.

A human barricade surrounding the Parliament, January 1991.

Photo: Aage Myhre.

With Landsbergis inside the Parliament, 19 January 1991, and his handwritten greeting to the editor.

Homemade barricades of concrete blocks around the Parliament.

Photo: Aage Myhre.

It was very touching to see how the Balts acted to keep their newfound freedom and protect their home country during the very difficult January days of 1991. Here, at the entrance to the Lithuanian Foreign Ministry, the young men have put on homemade clothes that are meant to look like uniforms. They carry rifles and other weapons they have found in their homes. Sand bags have an important symbolic effect. Brave guys!

Photo: Aage Myhre, 18 January 1991.

Inside the city armoured vehicles on rubber wheels were used. It was a bizarre, almost surreal experience to always be spotting, hearing the noise, feel the ground tremble when we were in meetings or trying to get a meal in one of the city's few restaurants.

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - (0) Comment

Lithuania’s Hill of Crosses

without equal in the world

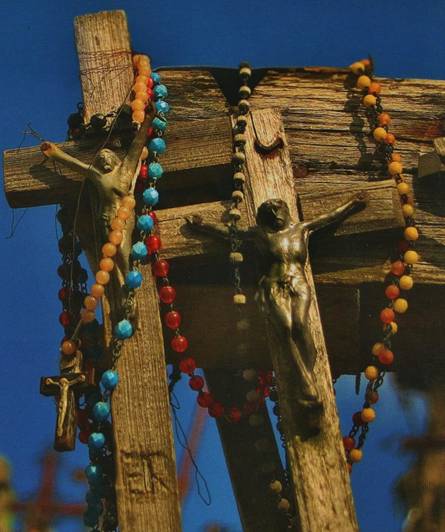

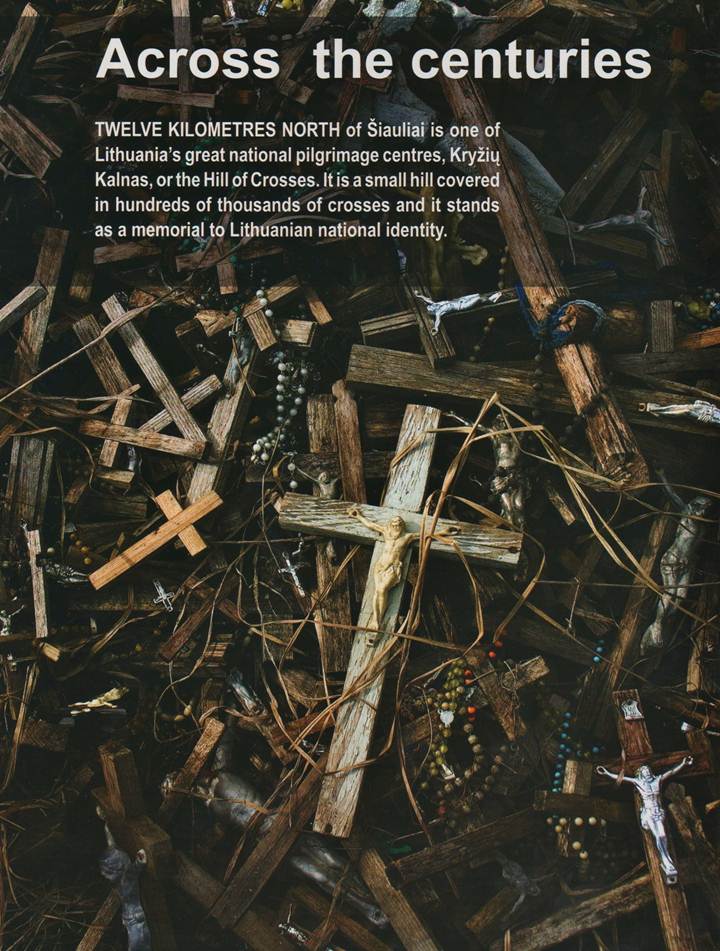

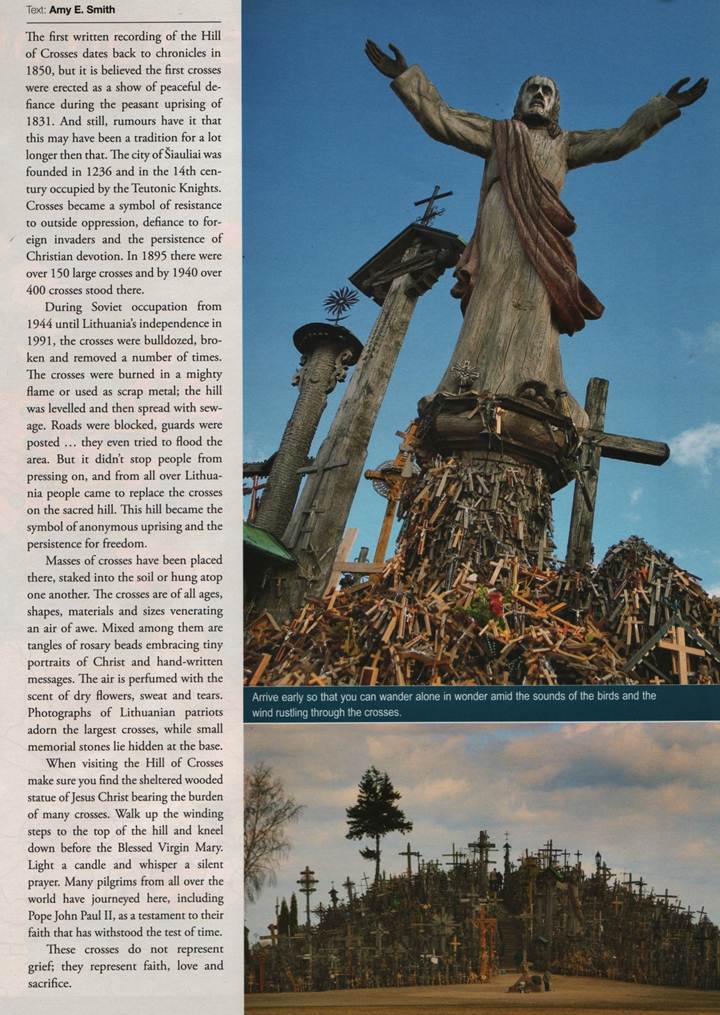

The Hill of Crosses (Lithuanian: Kryžių kalnas) is a site of pilgrimage about 12 km north of the city of Šiauliai, in northern Lithuania. The precise origin of the practice of leaving crosses on the hill is uncertain, but it is believed that the first crosses were placed on the former Jurgaičiai or Domantai hill fort after the 1831 Uprising. Over the centuries, not only crosses, but giant crucifixes, carvings of Lithuanian patriots, statues of the Virgin Mary and thousands of tiny effigies and rosaries have been brought here by Catholic pilgrims. The exact number of crosses is unknown, but estimates put it at about 100,000 in 2006.

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - (1) Comment

Lithuania’s Hill of Crosses

without equal in the world

The Hill of Crosses (Lithuanian: Kryžių kalnas) is a site of pilgrimage about 12 km north of the city of Šiauliai, in northern Lithuania. The precise origin of the practice of leaving crosses on the hill is uncertain, but it is believed that the first crosses were placed on the former Jurgaičiai or Domantai hill fort after the 1831 Uprising. Over the centuries, not only crosses, but giant crucifixes, carvings of Lithuanian patriots, statues of the Virgin Mary and thousands of tiny effigies and rosaries have been brought here by Catholic pilgrims. The exact number of crosses is unknown, but estimates put it at about 100,000 in 2006.

|

Number of crosses

|

|

Over the centuries, the place has come to signify the peaceful endurance of Lithuanian Catholicism despite the threats it faced throughout history. After the 3rd partition of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth in 1795, Lithuania became part of the Russian Empire. Poles and Lithuanians unsuccessfully rebelled against Russian authorities in 1831 and 1863. These two uprisings are connected with the beginnings of the hill: as families could not locate bodies of perished rebels, they started putting up symbolic crosses in place of a former hill fort.

When the old political structure of Eastern Europe fell apart in 1918, Lithuania once again declared its independence. Throughout this time, the Hill of Crosses was used as a place for Lithuanians to pray for peace, for their country, and for the loved ones they had lost during the Wars of Independence.

Most recently, the site took on a special significance during the years 1944–1990, when Lithuania was occupied by the Soviet Union. Continuing to travel to the Hill and leave their tributes, Lithuanians used it to demonstrate their allegiance to their original identity, religion and heritage. It was a venue of peaceful resistance, although the Soviets worked hard to remove new crosses, and bulldozed the site at least three times (including attempts in 1963 and 1973). There were even rumors that the authorities planned to build a dam on the nearby Kulvė River, a tributary to Mūša, so that the hill would end up under water.

On September 7, 1993, Pope John Paul II visited the Hill of Crosses, declaring it a place for hope, peace, love and sacrifice. In 2000 a Franciscan hermitage was opened nearby. The interior decoration draws links with La Verna, the mountain where St. Francis received his stigmata. The hill remains under nobody's jurisdiction; therefore people are free to build crosses as they see fit.

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - (0) Comment

|

IN MEMORY OF JEWISH KAUNAS |

Kaunas Ghetto (1941-1944):

An entire urban district turned into a merciless death camp

Two children in the Kaunas (Kovno) Ghetto, Lithuania.

Yad Vashem Photo Archive, 4789

What happened to the Jews in Lithuania during World War II is a matter of grim record. Of the 250.000 Jews in 1939, only between 12.500 and 17.500 survived; of those, only about 200 remain today.

It has been estimated that of the 265.000 Jews living in Lithuania in June 1941, 254.000 or 95% were murdered during the German occupation. No other Jewish community in Nazi-occupied Europe was so comprehensively destroyed.

The Red Army occupied Lithuania in June 1940, and the country remained under Soviet control until June 1941, when it fell to the invading German Army (Wehrmacht). On 8 July 1941 an order was issued stating that all Jews had to wear a special patch on their back; subsequently they were ordered to wear the patch on their chest. In addition Jews were forbidden to walk along the main streets of the city, and shops were ordered to sell them food in limited amounts. Jewish people were fired from their jobs, deprived of the means of personal transportation and radios, forbidden to use public transport, and prohibited from public places. Jews were arrested on the streets, at their work places, and in their houses.

The Kaunas (Kovno) Ghetto

Between 1920 and 1940, Kaunas (Kovno) was Lithuania's capital and largest city. It had a Jewish population of 35.000-40.000, about one-fourth of the city's total population. Jews were concentrated in the city's commercial, artisan, and professional sectors.

Kaunas was also a centre of Jewish learning. The yeshiva in Slobodka, an impoverished district of the city, was one of Europe's most prestigious institutions of higher Jewish learning, with a rich and varied Jewish culture. The city had almost 100 Jewish organizations, 40 synagogues, many Yiddish schools, 4 Hebrew high schools, a Jewish hospital, and scores of Jewish-owned businesses. It was also an important Zionist center.

Kaunas‘ Jewish life was disrupted when the Soviet Union occupied Lithuania in June 1940. The occupation was accompanied by arrests, confiscations, and the elimination of all free institutions. Jewish communal organizations disappeared almost overnight. Soviet authorities confiscated the property of many Jews. Meanwhile, the Lithuanian Activist Front, founded by Lithuanian nationalist emigres in Berlin, clandestinely disseminated antisemitic literature in Lithuania. Among other themes, the literature blamed Jews for the Soviet occupation. Hundreds of Jews were exiled to Siberia.

Following Germany's invasion of the Soviet Union on 22 June 1941, Soviet forces fled Kaunas. Immediately before and following the German occupation of the city on June 24, anti-Communist, pro-German Lithuanian mobs began to attack Jews (whom they unfairly blamed for Soviet repression), especially along Jurbarko and Krisciukaicio streets. These right-wing vigilantes murdered hundreds of Jews and took dozens more Jews to the Lietukis Garage, in the city center, and killed them there.

Moving into the Kovno Ghetto.

George Kadish, photographer, George Kadish, Florida.

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - (1) Comment

Kaunas Ghetto (1941-1944):

An entire urban district turned into a merciless death camp

Two children in the Kaunas (Kovno) Ghetto, Lithuania.

Yad Vashem Photo Archive, 4789

What happened to the Jews in Lithuania during World War II is a matter of grim record. Of the 250.000 Jews in 1939, only between 12.500 and 17.500 survived; of those, only about 200 remain today.

It has been estimated that of the 265.000 Jews living in Lithuania in June 1941, 254.000 or 95% were murdered during the German occupation. No other Jewish community in Nazi-occupied Europe was so comprehensively destroyed.

The Red Army occupied Lithuania in June 1940, and the country remained under Soviet control until June 1941, when it fell to the invading German Army (Wehrmacht). On 8 July 1941 an order was issued stating that all Jews had to wear a special patch on their back; subsequently they were ordered to wear the patch on their chest. In addition Jews were forbidden to walk along the main streets of the city, and shops were ordered to sell them food in limited amounts. Jewish people were fired from their jobs, deprived of the means of personal transportation and radios, forbidden to use public transport, and prohibited from public places. Jews were arrested on the streets, at their work places, and in their houses.

The Kaunas (Kovno) Ghetto

Between 1920 and 1940, Kaunas (Kovno) was Lithuania's capital and largest city. It had a Jewish population of 35.000-40.000, about one-fourth of the city's total population. Jews were concentrated in the city's commercial, artisan, and professional sectors.

Kaunas was also a centre of Jewish learning. The yeshiva in Slobodka, an impoverished district of the city, was one of Europe's most prestigious institutions of higher Jewish learning, with a rich and varied Jewish culture. The city had almost 100 Jewish organizations, 40 synagogues, many Yiddish schools, 4 Hebrew high schools, a Jewish hospital, and scores of Jewish-owned businesses. It was also an important Zionist center.

Kaunas‘ Jewish life was disrupted when the Soviet Union occupied Lithuania in June 1940. The occupation was accompanied by arrests, confiscations, and the elimination of all free institutions. Jewish communal organizations disappeared almost overnight. Soviet authorities confiscated the property of many Jews. Meanwhile, the Lithuanian Activist Front, founded by Lithuanian nationalist emigres in Berlin, clandestinely disseminated antisemitic literature in Lithuania. Among other themes, the literature blamed Jews for the Soviet occupation. Hundreds of Jews were exiled to Siberia.

Following Germany's invasion of the Soviet Union on 22 June 1941, Soviet forces fled Kaunas. Immediately before and following the German occupation of the city on June 24, anti-Communist, pro-German Lithuanian mobs began to attack Jews (whom they unfairly blamed for Soviet repression), especially along Jurbarko and Krisciukaicio streets. These right-wing vigilantes murdered hundreds of Jews and took dozens more Jews to the Lietukis Garage, in the city center, and killed them there.

Moving into the Kovno ghetto.

George Kadish, photographer, George Kadish, Florida.

Entrance gate to the Kaunas (Kovno) Ghetto (1941-1944).

Etching dated 1943, by Esther Lurie.

Street corner in the Kaunas Ghetto.

In early July 1941, German Einsatzgruppe (mobile killing unit) detachments and their Lithuanian auxiliaries began systematic massacres of Jews in several of the forts around Kaunas. These forts had been constructed by the Russian tsars in the nineteenth century for the defense of the city. Einsatzgruppe detachments and Lithuanian auxiliaries shot thousands of Jewish men, women, and children, primarily in the Ninth Fort, but also in the Fourth and Seventh forts. Within six months of the German occupation of the city, the Germans and their Lithuanian collaborators had murdered half of all Jews in Kaunas.

Ghetto street, November 1943.

Footbridge connecting the large and the small ghetto.

The Nazis established a civilian administration under SA Major General Hans Kramer. Between July and 15 August 1941, the Germans concentrated the remaining Jews, some 29.000 people, in a ghetto established in Slobodka. It was an area of small primitive houses and no running water. The ghetto had two parts, called the "small" and "large" ghetto, separated by Paneriu Street. In the autumn of 1943, the SS assumed control of the ghetto and converted it into the Kauen concentration camp. On 8 July 1944, the Germans evacuated the camp, deporting most of the remaining Jews to the Dachau concentration camp in Germany or to the Stutthof camp, near Danzig, on the Baltic coast. Three weeks before the Soviet army arrived in Kaunas, the German razed the ghetto to the ground with grenades and dynamite. As many as 2.000 people burned to death or were shot while trying to escape.

At its peak, the Ghetto held 40,000 people, most of whom were later sent to concentration and extermination camps, or were shot at the Ninth Fort. About 500 Jews escaped from work details and directly from the Ghetto, and joined Soviet partisan forces in the distant forests of southeast Lithuania and Belarus.

Youth in line for distribution of soup in the workers' kitchen in the Kaunas Ghetto.

The ghetto fire brigade with their chief Abramovitz (in front), August 1943.

Organization

The ghetto had two parts, called the "small" and "large" ghetto, separated by Paneriai Street and connected by a small wooden bridge over the street. Each ghetto was enclosed by barbed wire and closely guarded. Both were overcrowded, with each person allocated less than ten square feet of living space. The Germans continually reduced the ghetto's size, forcing Jews to relocate several times. The Germans and Lithuanians destroyed the small ghetto on October 4, 1941, and killed almost all of its inhabitants at the Ninth Fort. Later that same month, on 29 October 1941, the Germans staged what became known as the "Great Action." In a single day, they shot around 10,000 Jews at the Ninth Fort (see below).

The ghetto in Kovno provided forced labor for the German military. Jews were employed primarily as forced laborers at various sites outside the ghetto, especially in the construction of a military airbase in Aleksotas. The Jewish council (Aeltestenrat; Council of Elders), headed by Dr. Elkhanan Elkes, also created workshops inside the ghetto for those women, children, and elderly who could not participate in the labor brigades. Eventually, these workshops employed almost 6,500 people. The council hoped the Germans would not kill Jews who were producing for the army.

Jewish workers on their way back to the Ghetto after a day of forced labour.

|

The Underground School As an act of defiance an underground school was conducted in the Kovno Ghetto when such education was banned in 1942. A remarkable photo of one of the classes of that school features in the US Holocaust publication, "The Hidden History of the Kovno Ghetto". Identification of the teacher visible in that photo is given in a website that deals with the hidden school. However almost all of the children in the Ghetto, approximately 2,500, were removed in the Kinder Aktion of 27–28 March 1944. |

|

Unidentified child in the Kaunas Ghetto, 1943.

www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/jsource/Holocaust/finkelsteinkovno.html

Smuggling Babies out of the Ghetto

From 1942 births were not permitted in the ghetto and pregnant women faced death. However a number of babies of ages from about 9 months to 15 months were smuggled out of the Kovno Ghetto to willing Lithuanian foster mothers.

Final days

In the autumn of 1943, the SS assumed control of the ghetto and converted it into the Kovno concentration camp. The Jewish council's role was drastically curtailed. The Nazis dispersed more than 3,500 Jews to subcamps where strict discipline governed all aspects of daily life. On October 26, 1943, the SS deported more than 2,700 people from the main camp. The SS sent those deemed fit to work to Vaivara concentration camp in Estonia, and deported surviving children and the elderly to Auschwitz.

On 8 July 1944, the Germans evacuated the camp, deporting most of the remaining Jews to the Dachau concentration camp in Germany or to the Stutthof camp, near Danzig, on the Baltic coast. Three weeks before the Soviet army arrived in Kovno, the Germans razed the ghetto to the ground with grenades and dynamite. As many as 2,000 people burned to death or were shot while trying to escape the burning ghetto. The Red Army occupied Kaunas on 1 August 1944. Of Kaunas‘ few Jewish survivors, 500 had survived in forests or in a single bunker which had escaped detection during the final liquidation; the Germans evacuated an additional 2,500 to concentration camps in Germany.

Jewish women standby murdered corpses outside

the Seventh Fort in Kaunas.

Resistance

Throughout the years of hardship and horror, the Jewish community in Kaunas documented its story in secret archives, diaries, drawings and photographs. Many of these artifacts lay buried in the ground when the ghetto was destroyed. Discovered after the war, these few written remnants of a once thriving community provide evidence of the Jewish community's defiance, oppression, resistance, and death. George Kadish (Hirsh Kadushin), for example, secretly photographed the trials of daily life within the ghetto with a hidden camera through the buttonhole of his overcoat.

Monument of the Kaunas Ghetto

The Kovno ghetto had several Jewish resistance groups. The resistance acquired arms, developed secret training areas in the ghetto, and established contact with Soviet partisans in the forests around Kaunas.

In 1943, the General Jewish Fighting Organization (Yidishe Algemeyne Kamfs Organizatsye) was established, uniting the major resistance groups in the ghetto. Under this organization's direction, some 300 ghetto fighters escaped from the Kovno ghetto to join Jewish partisan groups. About 70 died in action.

The Jewish council in Kaunas actively supported the ghetto underground. Moreover, a number of the ghetto's Jewish police participated in resistance activities. The Germans executed 34 members of the Jewish police for refusing to reveal specially constructed hiding places used by Jews in the ghetto.

The completely destroyed Kaunas Ghetto. In July 1944, the Germans blew up and

burned down the ghetto in search of Jews in hiding there.

Read more…

http://www.ushmm.org/museum/exhibit/online/kovno/intro/intro.htm

http://www.ushmm.org/wlc/en/article.php?ModuleId=10005174

http://www.holocaustresearchproject.org/ghettos/kovno.html

http://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/jsource/Holocaust/kovnotoc.html

http://www.fold3.com/page/286123943_the_kovno_ghetto_partisans_chaim_yelin/

http://www.lithuanianjews.org.il/HTMLs/article_list4.aspx?C2014=14287&BSP=14432&BSS59=14432

http://www.aish.com/ho/p/48949791.html

Books:

http://jewishhistoryaustralia.net/TheHistoryOfNow/Kovno/resource.php

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - (0) Comment

|

IN MEMORY OF JEWISH KAUNAS |

Chiune Sugihara:

The Japanese diplomat/

spy who became a hero of the Holocaust

By Boris Bakunas, PhD

In the Year of Shame 1940, while the bulk of the German military machine was consolidating its grip on Poland, 110 French and British divisions sat idly on the Western Front, facing a token German force a fraction its size.

In the Year of Shame 1940, the People’s Commissariat for Internal Affairs, the dreaded NKVD, massacred 22,000 captured members of the Polish Officer Corps, turning the Katyn Forest into a vast mass grave.

In that same Year of Shame 1940, Chiune Sugihara, a Japanese diplomat and spy stationed in Kaunas, Lithuania – along with his wife Yukiko – made a joint decision in defiance of direct orders from their government, and together they lit a beacon of hope for thousands of Polish and Lithuanian Jews. From 19 July to 28 August, 1940, the two-storey, white stucco building on 30 Vaizgantas Street that housed the Japanese Consulate, became the moral capital of the world.

Chiune and Yukiko Sugihara with their two children had arrived in Kaunas from Helsinki in 1939 not long after Nazi and Soviet troops sliced Poland into two zones of terror. Chiune’s ostensible mission was to serve as the Japanese Vice-Consul in Kaunas. His real assignment was to gather intelligence on the strength of the Soviet military in the West.

But a chance encounter at a delicatessen with an eleven-year-old Lithuanian-Jewish boy named Solly Ganor intervened, transforming the suave foreign-service officer renowned in diplomatic circles for throwing lavish parties into a hero of the Holocaust.

Jewish refugees at the gate of the Japanese Consulate in Kaunas,

July 1940. Thousands of Jews lined up here, hoping to receive transit visas allowing them to escape to the Far East and to America or Palestine.

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

VilNews e-magazine is published in Vilnius, Lithuania. Editor-in-Chief: Mr. Aage Myhre. Inquires to the editors: editor@VilNews.com.

Code of Ethics: See Section 2 – about VilNews. VilNews is not responsible for content on external links/web pages.

HOW TO ADVERTISE IN VILNEWS.

All content is copyrighted © 2011. UAB ‘VilNews’.

Click on the buttons to open and read each of VilNews' 18 sub-sections

Click on the buttons to open and read each of VilNews' 18 sub-sections

.jpg)