THE VOICE OF INTERNATIONAL LITHUANIA

|

VilNews has its own Google archive! Type a word in the above search box to find any article.

You can also follow us on Facebook. We have two different pages. Click to open and join.

|

Archive for February, 2012

- Posted by - Comments (0)

The Polish-Lithuanian

War 1919-1920

Part 3 of 4 - STRUGGLES for the VILNIUS REGION

Map of the (Polish) Republic of Central Lithuania (in green).

By Vincas Karnila, Associate editor

vin.karnila@VilNews.com

ZELIGOWSKI’S MUTINY

Polish chief of state Jozef Pilsudski ordered his subordinate, General Lucjan Zeligowski, to stage a mutiny with his 1st Lithuanian–Belarusian Division (16 battalions with 14,000 soldiers) in Lida and capture Vilnius in fait accompli.

The rebellion had two main goals, capture Vilnius and preserve Polish international reputation. The League of Nations was mediating other Polish disputes, notably over the Free City of Danzig and Upper Silesia, and direct aggression against Lithuania could have hampered Polish bargaining positions. While the Polish side officially stated Żeligowski to be a deserter and did not support him, Poland provided logistic support, including munitions and food rations, to his units. Żeligowski also received reinforcements when, according to the official version, the mutiny spread further among the Polish troops. His initial attack was secured on both sides by two Polish Armies.

The Żeligowski's Mutiny, in planning since mid-September, began in the early morning on October 8, 1920, just few hours after the signing of the Suwałki Agreement. A provisional agreement was made in the Polish–Soviet War, which freed up Polish units for the attack on Lithuania. As part of the rouse, Żeligowski wrote a note to Polish command announcing his mutiny and expressing his disappointment with the Suwałki Agreement. He claimed that his troops marched to defend the right of self-determination of the local Polish population.

READ TODAY’S ARTICLE – PART 3 OF 4

To read previous articles – GO TO OUR SECTION 10

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - Comments (0)

The Polish-Lithuanian

War 1919-1920

Part 3 of 4 – STRUGGLES for the VILNIUS REGION

Map of

the (Polish) Republic of Central Lithuania (in green).

Su pagarbe Vincas Karnila, Associate editor

vin.karnila@VilNews.com

ZELIGOWSKI’S MUTINY

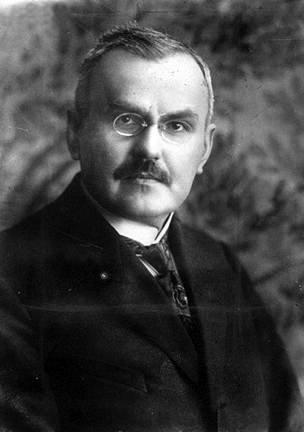

Polish chief of state Jozef Pilsudski ordered his subordinate, General Lucjan Zeligowski, to stage a mutiny with his 1st Lithuanian–Belarusian Division (16 battalions with 14,000 soldiers) in Lida and capture Vilnius in fait accompli.

Lucjan

Zeligowski

The rebellion had two main goals, capture Vilnius and preserve Polish international reputation. The League of Nations was mediating other Polish disputes, notably over the Free City of Danzig and Upper Silesia, and direct aggression against Lithuania could have hampered Polish bargaining positions. While the Polish side officially stated Żeligowski to be a deserter and did not support him, Poland provided logistic support, including munitions and food rations, to his units. Żeligowski also received reinforcements when, according to the official version, the mutiny spread further among the Polish troops. His initial attack was secured on both sides by two Polish Armies.

The Żeligowski's Mutiny, in planning since mid-September, began in the early morning on October 8, 1920, just few hours after the signing of the Suwałki Agreement. A provisional agreement was made in the Polish–Soviet War, which freed up Polish units for the attack on Lithuania. As part of the rouse, Żeligowski wrote a note to Polish command announcing his mutiny and expressing his disappointment with the Suwałki Agreement. He claimed that his troops marched to defend the right of self-determination of the local Polish population.

CAPTURE of VILNIUS and other MILITARY ATTACKS

Lithuanians were not prepared for the assault. They had only two battalions, stationed near Jašiūnai and Rūdninkai along the Merkys River, shielding the city from Poland’s troops. Their main forces were still in the Suwałki Region and to the west from Druskininkai and Varėna. Without the railway, Lithuanian units could not be easily redeployed to protect Vilnius. After it became clear that Żeligowski would not stop in Vilnius, Commander of the Lithuanian Army Silvestras Žukauskas, who took the position only on October 6, ordered to evacuate the city in the afternoon on October 8.

Silvestras

Žukauskas

They left the city's administration to Entente official Constantin Reboul. Żeligowski entered Vilnius the following evening. He did not recognize Reboul's authority and Entente officials left the city in protest. On October 12, Żeligowski proclaimed the independence of the (Polish) Republic of Central Lithuania, with Vilnius as its capital. The name was inline with Piłsudski's vision of historical Lithuania, divided into three cantons: Lithuanian-inhabited Western Lithuania with its capital in Kaunas, Polish-inhabited Central Lithuania with its capital in Vilnius, and Belarusian-inhabited Eastern Lithuania with its capital in Minsk. Further developments of other cantons was prevented by the Polish National Democracy, a party opposed to Piłsudski's federalist ideas.

Żeligowski's units continued to advance. Territories east of the city were taken without resistance while Lithuanians defended in the west. Żeligowski took Švenčionys and Rūdiškės on October 10, Nemenčinė on October 11, Lentvaris on October 13 and Rykantai on October 15. The front somewhat stabilized on the southern (left) side of the Neris River, but fighting continued on the northern (right) side of Neris. When Polish cavalry maneuvered towards Riešė, it learned from the local population the location of the command of the Lithuanian 1st Riflemen Regiment. On October 21, the cavalry raided the village and took the entire command prisoners. Left without their commanders, the Lithuanians retreated and Poles took Maišiagala and Paberšė. On October 26, another cavalry raid captured Dubingiai, Giedraičiai, Želva and threatened Ukmergė. However, Lithuanians counterattacked and took back Želva on October 30 and Giedraičiai on November 1. For a while the front stabilized.

On November 17, the mutineers began a major attack. They planned to capture Kaunas, thus threatening Lithuanian independence, by encircling the city from north through Širvintos-Ukmergė-Jonava and Giedraičiai –Kavarskas–Kėdainiai. Żeligowski's forces were about three times larger, 15 Polish battalions against 5 Lithuanian battalions. One cavalry brigade managed to break through the Lithuanian defense lines near Dubingiai, reached Kavarskas, and continued towards Kėdainiai. However, Lithuanians were successful in stopping an attack towards Ukmergė near Širvintos on November 19. About 200 Lithuanians maneuvered through swaps to the rear of three Polish battalions. Attacked from front and rear, some 200 Poles were taken prisoners while others retreated. Lithuanians continued to attack and captured Giedraičiai on November 21. On the same day a ceasefire was signed under pressure from the League of Nations. The Polish cavalry brigade, pushed from Kėdainiai and cut off from its main forces, retreated through Ramygala–Troškūnai–Andrioniškis–Lėliūnai and rejoined other Żeligowski units on November 24. These were the last military movements in the Polish–Lithuanian conflict.

MEDIATION and DIPLOMATIC MEASURES

On October 11, 1920, Lithuanian envoy in Paris Oscar Milosz asked the League of Nations to intervene in the renewed conflict with Poland. On October 14, Chairman of the League Léon Bourgeois issued a note condemning the aggression and asking Polish units to retreat. Politicians in London even considered expelling Poland from the League.

When the League heard both arguments on October 26–28, Polish envoy Szymon Askenazy claimed that there was no conflict between Poland and Lithuania to mediate. He maintained that the old conflict ended with signing ceasefires with Lithuania on October 7 and with Soviet Russia on October 12 and the new conflict was caused by Żeligowski, who acted without approval from the Polish command, but with moral support of the entire Polish nation. Lithuanian envoy Augustinas Voldemaras argued that Poland orchestrated the mutiny and demanded strict sanctions against Poland. The League refused to validate Żeligowski's action. It suggested to hold a referendum vote in the contested areas. On November 6 and 7, both sides agreed and Lithuanians began preparatory work.

On November 19, Żeligowski proposed the Control Commission, led by Chardigny, to cease hostilities. Lithuanians agreed and a ceasefire was signed on November 21. Later this episode was criticized by Lithuanian commentators as at the time the Lithuanian Army had initiative in the front and had a chance of marching on Vilnius. However, the Lithuanians trusted the League of Nations would resolve the dispute in their favor and were also afraid that in the case of their attack on Vilnius regular Polish forces would arrive to reinforce Żeligowski's units.

Negotiations for a more permanent armistice, under mediation of the Control Commission, began on November 27 in Kaunas. Lithuania did not agree to negotiate directly with Żeligowski and thus legitimizing his actions therefore, Poland stepped in as a mediator. Lithuania agreed as it hoped to put the talks back into the context of the Suwałki Agreement. Poles rejected any withdrawal of Żeligowski's forces. No agreement could be reached regarding a demarcation line and on November 29, 1920, it was agreed only to cease hostilities on November 30, to entrust the Control Commission with establishment of a 6 km (3.7 mi) wide neutral zone and to exchange prisoners. This neutral zone existed until February 1923.

In part 4 of 4 - The Aftermath

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

![]()

Just to confirm that she does get her challenging work done, check out Barbara's popular online magazine Indulged Traveler at http://www.indulgedtraveler.com and find the best destinations, jewellery, hotels, food and fashion, wine regions and cooking lessons. Her email address is barbara3@rogers.com

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

Barbra Kingstone finds Lithuania increasingly cosmopolitan – but not easy to read and walk…

- Posted by - Comments (0)

![]()

BARBARA KINGSTONE: Charming as the Vilnius cobblestone streets are, if you're walking, these uneven surfaces are a hazard so sensible shoes. As I traversed the ancient streets, it boggled my mind to see svelte young women in sky-high stilettos rush by without a wobble.

Photo: Aage Myhre.

An article by BARBARA KINGSTONE,

Special to QMI Agency

Some countries can be read like a manageable road map. It's easy to figure out where you are, learn about the history and politics, and navigate from one dot to another. Lithuania is not one of these.

With its history of political twists and turns, domination by various countries, shifting borders, and imposed ideologies, connecting the dots in Lithuania is complex. When likened to reading a map, even the most directionally adept person would beg for aspirin.

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

The fairy tale forests of the Gauja Valley in Latvia, the beauty of Saaremaa Island in Estonia and the 170-foot-high Parnidis Dune in Lithuania were waiting for author Patricia Schultz to discover them

- Posted by - Comments (0)

![]()

Patricia Schultz’s world bestselling travel book is back in a more informative, more experiential, more budget-friendly full-color edition. A #1 "New York Times" bestseller, "1,000 Places" reinvented the idea of travel book as both wish list and practical guide. As Newsweek wrote, it "tells you what's beautiful, what's fun, and what's just unforgettable-- everywhere on earth." And now the best is better. There are 600 full-color photographs. Over 200 entirely new entries, including visits to 28 countries like Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia, that were not in the original edition.

On top of the Parnidis Dune,

Neringa, Lithuania.

Photo: Aage Myhre.

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - Comments (0)

Kazimiera Prunskiene:

Russian direction is necessity, not a threat

By Linas Jegelevicius. Baltic Times

Twenty years ago she was called the Baltics’ Amber Lady, who led Lithuania to its independence, but today the KGB collaboration shadow haunts Kazimiera Danute Prunskiene, even though she has successfully fought off this accusation in court. Out of the Lithuanian Parliament and ousted from the chairwomanship of the Lithuanian Peasant Popular Union, in 2009, instead of enjoying life out of politics, she established the pro-Russian Lithuanian Populace Party (LPP), which is said to be of increased interest to Lithuania’s State Security Department. Though the party was doomed to defeat in the municipality elections in 2011, it was among the parties to have gained the biggest financial contributions from electoral campaign donors. The first prime minister of independent Lithuania and, currently, chairwoman of the controversial Lithuanian Populace Party, sat down with The Baltic Times for this interview.

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

![]()

BY NIKOLAJ NIELSEN

BRUSSELS - The number of unemployed people in Europe is reaching record highs as the economic crisis unfolds into one with significant social consequences.

In eight member states alone, over 30 percent of young people under 25 are out of jobs. The worst affected continues to be Spain where half its young are jobless.

UNEMPOLYMENT IN LITHUANIA:

Youth unemployment: 31.1%

Overall unemployment: 15.3%

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - Comments (1)

The Polish-Lithuanian

War 1919-1920

A series of articles in 4 parts

By Vincas Karnila, Associate editor

vin.karnila@VilNews.com

South-eastern Lithuania, Vilnius included, was occupied by Poland during the interwar period.

Picture: Celebration of the incorporation of Vilnius Region to Poland, 1922.

The Polish–Lithuanian War was an armed conflict between Lithuania and Poland in the aftermath of World War I and Lithuania's declaration of independence 16 February 1918.

The conflict primarily concerned territorial control of the Vilnius Region, including Vilnius, and the Suwałki Region, including the towns of Suwałki, Augustów, and Sejny. According to Lithuanian historians, the war was part of the Lithuanian Wars of Independence and spanned from spring 1919 to November 1920. According to Poland, the war included only fighting over the Suwałki Region in September–October 1920 and was part of the Polish–Soviet War.

After Vilnius was occupied by the Russian Bolsheviks in 1919, the government of the Republic of Lithuania established its main base in Kaunas. When Vilnius was forcibly annexed by Poland, Kaunas became the temporary capital of Lithuania, a position it held until 28 October 1939, when the Red Army handed Vilnius back to Lithuania. The Constituent Assembly of Lithuania first met in Kaunas on 15 May 1920. There were no diplomatic relations between Poland and Lithuania until 1938.

|

Part 1 – THE BUILD UP World War I ended on November 11, 1918 when Germany signed the Compiègne Armistice. On November 13, Soviet Russia renounced the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk. Most of today's Poland, Belarus, Ukraine and the Baltic States were passed to the government of Germany, which in turn decided to grant these states limited independence as buffer states) and began the Soviet westward offensive of 1918–1919. |

|

Part 2 – ADVANCES and RETREATS In April 1920 Poland launched the large-scale Kiev Offensive in hopes to capture Ukraine. Initially successful, the Polish Army started retreating after Russian counterattacks in early June 1920. Soon the Soviet forces began to threaten Poland's independence as they reached and crossed the Polish borders. |

|

Part 3 – STRUGGLES for the VILNIUS REGION Polish chief of state Jozef Pilsudski ordered his subordinate, General Lucjan Zeligowski, to stage a mutiny with his 1st Lithuanian–Belarusian Division (16 battalions with 14,000 soldiers) in Lida and capture Vilnius in fait accompli. |

|

Part 4 – THE AFTERMATH In March 1921, the plans for a referendum vote were abandoned. Neither Lithuania, which was afraid of a negative result, nor Poland, which saw no reason to change status quo, wanted it. The parties could not agree in which territory to carry out the vote and how Żeligowski's forces should be replaced by the League's forces. The League of Nations then moved on from trying to solve the narrow territorial dispute in the Vilnius Region to shaping the fundamental relationship between Poland and Lithuania. |

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - Comments (0)

The Polish-Lithuanian

War 1919-1920

Part 2 of 4 - ADVANCES and RETREATS

The Battle of the Niemen River was the second-greatest battle of the Polish-Soviet War. It took place near the Neman River between the cities of Suwałki, Grodno and Białystok in today’s Poland and Belarus.

Su pagarbe Vincas Karnila, Associate editor

vin.karnila@VilNews.com

DIPLOMATIC DEVELOPMENTS

In April 1920 Poland launched the large-scale Kiev Offensive in hopes to capture Ukraine. Initially successful, the Polish Army started retreating after Russian counterattacks in early June 1920. Soon the Soviet forces began to threaten Poland's independence as they reached and crossed the Polish borders. On July 9, Polish Prime Minister Wladyslaw Grabski asked the Allied Powers in the Spa Conference (The Spa Conference was a meeting between the Supreme War Council and Weimar Republic in Spa, Belgium on 5–16 July 1920).

READ TODAY’S ARTICLE – PART 2 OF 4

To read previous articles – GO TO OUR SECTION 10

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - Comments (0)

The Polish-Lithuanian

War 1919-1920

Part 2 of 4 - ADVANCES and RETREATS

The Battle of the Niemen River was the second-greatest battle of the Polish-Soviet War. It took place near the Neman River between the cities of Suwałki, Grodno and Białystok in today’s Poland and Belarus.

Su pagarbe Vincas Karnila, Associate editor

vin.karnila@VilNews.com

DIPLOMATIC DEVELOPMENTS

In April 1920 Poland launched the large-scale Kiev Offensive in hopes to capture Ukraine. Initially successful, the Polish Army started retreating after Russian counterattacks in early June 1920. Soon the Soviet forces began to threaten Poland's independence as they reached and crossed the Polish borders. On July 9, Polish Prime Minister Wladyslaw Grabski asked the Allied Powers in the Spa Conference (The Spa Conference was a meeting between the Supreme War Council and Weimar Republic in Spa, Belgium on 5–16 July 1920).

It was the first post-war conference to include German representatives. The attendees included British and French Prime Ministers Lloyd George and Alexandre Millerand, German Chancellor Constatin Fehrenbach. The Conference mainly discussed disarmament of Germany and war reparations required by the Treaty of Versailles) for military assistance in the war with the Soviets. The conference proposed that the Polish forces would withdraw behind the Curzon Line, the Soviet forces would stop 50 km (31 mi) to the east of the line, the Lithuanian forces would take control of Vilnius, and all other disputes would be settled via negotiations in London. Grabski opposed the transfer of Vilnius, but under pressure of British Prime Minister Lloyd George, agreed to the resolution on July 10.

Advance of Soviet forces (red arrows) against Polish troops in June–August 1920

At the same time the Soviets and Lithuania negotiated the Soviet–Lithuanian Peace Treaty, which was signed on July 12, 1920. Russia recognized Lithuanian independence and withdrew any territorial claims. The treaty drew the eastern border of Lithuania, which the Lithuanians continued to claim as their de jure state border until World War II. The Vilnius Region, including Braslau, Hrodna, Lida and Vilnius, was recognized to Lithuania. On August 6, after long and heated negotiations, Lithuania and Soviet Russia signed a convention regarding withdrawal of Russian troops from the recognized Lithuanian territory. However, the troops began to retreat only after the Red Army suffered a heavy defeat in Poland.

TERRITORIAL CHANGES

The Bolshevik forces reached the Lithuanian territory on July 7, 1920, and continued to push back the Polish troops and subsequently the Lithuanian Army moved to secure territories abandoned by the retreating Polish forces. They took Turmantas on July 7, Tauragnai and Alanta on July 9, Širvintos and Musninkai on July 10, Kernavė, Molėtai and Giedraičiai on July 11, Maišiagala and Pabradė on July 13. On July 13 the Polish command decided to transfer Vilnius to the Lithuanians in accordance with the resolution of the Spa Conference. Lithuanians tried to move in but their trains were stopped by Polish soldiers near Kazimieriškės. This delay meant that the Bolsheviks were the first to enter Vilnius on July 14. By the time the first Lithuanian troops entered the city on July 15, it was already secured by the Soviets. Poland sought to have Russians in the city as it would create much less complications when Polish Army counterattacked. Despite the Peace Treaty, the Soviets did not intend to transfer the city to the Lithuanians. Indeed there were indications that the Soviets planned a coup against the Lithuanian government in hopes to establish the Lithuanian SSR (Lithuanian Soviet Socialist Republic)

Despite the setback in Vilnius, the Lithuanians continued to secure territories in the Suwałki Region. Lithuanian forces took Druskininkai on July 17, Vištytis, Punsk, Giby, and Sejny on July 19, Suwałki on July 29 and Augustów on August 8. The Polish units, afraid of being surrounded and cut off from the main Polish forces, retreated towards Lomza. The Lithuanian authorities started to organize themselves in the regained areas.

LITHUANIAN NEUTRALITY

Poland claimed that Lithuania violated its claim to neutrality in the Polish–Soviet War and in effect became a Soviet ally. A secret clause of the Soviet–Lithuanian Peace Treaty allowed Soviet forces unrestricted movement within the Soviet-recognized Lithuanian territory for the duration of Soviet hostilities with Poland. This clause was more of a practical matter since Soviet troops already occupied much of the assigned territory and could not and would not withdraw while hostilities with Poland continued. Lithuanians were also simply unable to resist the Soviets and their troops. For example, when Lithuanians refused a permission to use a road, the Soviets ignored Lithuanian protests and transported their troops and equipment regardless. At the same time Polish soldiers were disarmed and interned bt Lithuania. The largest group, a brigade under colonel Pasławski, was interned on July 18, 1920, near Kruonis. On August 10, Lithuanians held 103 Polish officers and 3,520 private soldiers. Poland also claimed that the Lithuanian troops actively participated in military operations of the Red Army. This charge, based on memoirs of Soviet officials, lacks evidence. Further military clashes between Polish and Lithuanian troops in the Suwałki Region were interpreted by Poland to show that "the Lithuanian government has become an instrument of the Soviet government." Lithuania responded that it was defending its borders.

AUGUST to OCTOBER 1920 – STRUGGLES FOR THE SUWALKI REGION

POLISH ADAVANCE AND SOVIETS RETREAT

The Russians suffered a great defeat AT the Battle of Warsaw in mid-August 1920 and started withdrawing. They handed over Vilnius to the Lithuanians on August 26. The Lithuanians hastily made preparations to secure the border, as determined by the Soviet–Lithuanian Peace Treaty. The soldiers were ordered to maintain neutrality: avoid hostilities and intern any Soviet or Polish troops that would cross the border. On August 26, a Polish delegation, led by colonel Mieczyslaw Mackiewicz, arrived in Kaunas to negotiate the situation. The Poles, lacking authority to discuss political issues, were concerned with military aspects.

They sought permission to transport Polish troops through the territory of Lithuania, wanted access to a portion of the Warsaw–Saint Petersburg Railway and demanded that the Lithuanian troops would withdraw from the Suwałki Region behind the Curzon Line. The Lithuanians refused to discuss military matters without a clear political Polish–Lithuanian border that would be respected after the war. Due to these fundamental disagreements and Polish attacks, the negotiations broke down on August 30.

Map of the Suwałki Region. Its many forests and lakes complicated the military actions.

The Suwałki Region had strategic importance in the Polish–Soviet War. Following orders of Edward Rydz-Śmigły, Polish forces took Augustów from Lithuanians in a surprise attack on August 28. Confused and disoriented Lithuanians retreated from Suwałki and Sejny on August 30 and 31. The Lithuanians reorganized, gathered their forces (11 battalions with 7,000 soldiers) and organized a counterattack to "defend their border" on September 2. The goal was to take and secure the Augustów–Lipsk-Hrodna line. The Lithuanians succeeded in taking Sejny and Lipsk and by September 4 reached the outskirts of Augustów. On September 5, the Poles counterattacked and forced the Lithuanians to retreat. On September 9, the Polish forces recaptured Sejny but the Lithuanians pushed back and regained Sejny and Giby on September 13 and 14. Pending direct negotiations, hostilities were ceased on both sides.

DIRECT NEGOTIATIONS and the LEAGUE OF NATIONS

On September 6, Lithuanian Foreign Minister Juozas Purickis proposed direct negotiations in Marijampolė. On September 8, during a planning meeting of the Battle of the Niemen River, the Poles decided to maneuver through the Lithuanian territory to the rear of the Soviet Army, stationed in Hrodna In an attempt to conceal the planned attack, Polish diplomats accepted the proposal to negotiate. The negotiations started on September 16 in Kalvarija but collapsed just two days later.

Juozas Purickis

On September 5, 1920, Polish Foreign Minister Eustachy Sapieha delivered a diplomatic note to the League of Nations alleging that Lithuania violated its neutrality and asking to intervene in the Polish–Lithuanian War.

The League agreed to mediate and began its session on September 16. The resolution, adopted on September 20, urged both states to cease hostilities and adhere to the Curzon Line. Poland was asked to respect Lithuanian neutrality if Soviet Russia agreed to do the same. Also a special Control Commission was to be dispatched into the conflict zone to oversee implementation of the resolution. It was clear that the League had only a narrow goal to prevent armed hostilities and not to resolve the underlying territorial dispute. The Lithuanian government accepted the resolution, while Poland reserved full freedom of action in preparation for the attack on the Soviets.

BATTLE of the NIEMAN RIVER

On September 22, 1920, Poland attacked Lithuanian units in the Suwałki Region on a wide front. Overwhelmed by 4–5 times larger enemy forces, some 1,700–2,000 Lithuanian troops surrendered and were taken prisoners. Polish forces then marched, as planned on September 8, across the Neman River near Druskininkai and Merkinė to the rear of the Soviet forces near Hrodna and Lida. The Red Army hastily retreated. The Lithuanians had limited intelligence warnings about such attack and as a result chose an inadequate defensive strategy and spread their forces too thinly along the entire Polish–Lithuanian front without sufficient forces to protect bridges across the Neman.

Map of the Battle of the Niemen river. Polish forces maneuvered through the Lithuanian territory (front line in red) to the rear of Soviet troops despite the resolution by the League of Nations to cease hostilities

This attack, just two days after the resolution by the League of Nations to cease hostilities, put more pressure on Poland to settle the dispute peacefully. On September 26, Poles captured Hrodna and Polish Foreign Minister Sapieha proposed new negotiations in Suwałki. The Battle of the Niemen River drastically altered the balance of power. Vilnius, in Lithuanian hands since August 26, was exposed to a Polish attack. Indeed Poles had already decided to capture the city and used the negotiations in Suwałki to stall and buy time for necessary preparations. The Lithuanian side was ready to give up the Suwałki Region in exchange for Poland's recognition of the Lithuanian claims to Vilnius.

SUWALKI AGREEMENT

The negotiations between Poles, led by colonel Mieczyslaw Mackiewicz and Lithuanians led by general Maksimas Katche, began in the evening of September 29, 1920. Both sides agreed to an armistice, but only to the east of the Neman River (the Suwałki Region).

Fighting to the west on the river continued around Marcinkonys, Zervynos, Perloja and Eišiškės. A major point of contention, both diplomatic and military, was the train station in rėna (Orany) on the Warsaw – Saint Petersburg Railway. Major Lithuanian forces were still concentrated in the Suwałki Region and moving them to protect Vilnius without the railway would be extremely difficult. Fighting west of the Neman River ceased only on October 6, when Polish troops had already captured the train station in Varėna.

Selected demarcation lines between Poland and Lithuania. Line drawn by the Suwałki Agreement is in yellow; the final interwar border is in orange. The current borders of Lithuania, Poland and Balta Rusija that were established after the Second World War are indicated by the purple lines

Negotiations regarding the demarcation line were difficult. In essence, the Lithuanians wanted a longer demarcation line to provide better protection for Vilnius. The Poles agreed only to a short line in order to provide the planned attack on Vilnius with space for operation. The Polish delegation was also stalling to buy time for necessary preparations for an attack on Vilnius. While Vilnius was not a topic of debate, it was on everybody's mind. On October 4, the Control Commission, sent by the League according to its resolution of September 20, arrived to Suwałki. The Commission, led by French colonel Pierre Chardigny, re-energized the negotiations. On October 7, at midnight, the final agreement was signed. The treaty made not a single reference to Vilnius or the Vilnius Region. The ceasefire was effective only along the demarcation line, which ran through the Suwałki Region to the train station in Bastuny. Thus the line was incomplete, did not provide protection to the Vilnius Region, but indicated it would be left on the Lithuanian side.

In Part 3

OCTOBER to NOVEMBER 1920 – STRUGGLES for the VILNIUS REGION

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - Comments (0)

Re. Polish-Lithuanian War 1919-1920:

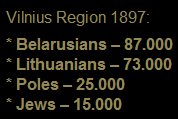

Thank you for the very interesting post. The demographics in 1897 is provided here

Interestingly in the areas around Vilnius, excluding the city ("Vilenskij ujezd bez goroda") Belarusians constituted around 87 000, Poles 25 000, Lithuanians 73 000, and Jews 15 000. So it was a very mixed area, and I wonder if "Belarusians" became "Poles" in later censuses.

Tautietis

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

VilNews e-magazine is published in Vilnius, Lithuania. Editor-in-Chief: Mr. Aage Myhre. Inquires to the editors: editor@VilNews.com.

Code of Ethics: See Section 2 – about VilNews. VilNews is not responsible for content on external links/web pages.

HOW TO ADVERTISE IN VILNEWS.

All content is copyrighted © 2011. UAB ‘VilNews’.

Click on the buttons to open and read each of VilNews' 18 sub-sections

Click on the buttons to open and read each of VilNews' 18 sub-sections

.jpg)