THE VOICE OF INTERNATIONAL LITHUANIA

|

VilNews has its own Google archive! Type a word in the above search box to find any article.

You can also follow us on Facebook. We have two different pages. Click to open and join.

|

Author Archive

- Posted by - (0) Comment

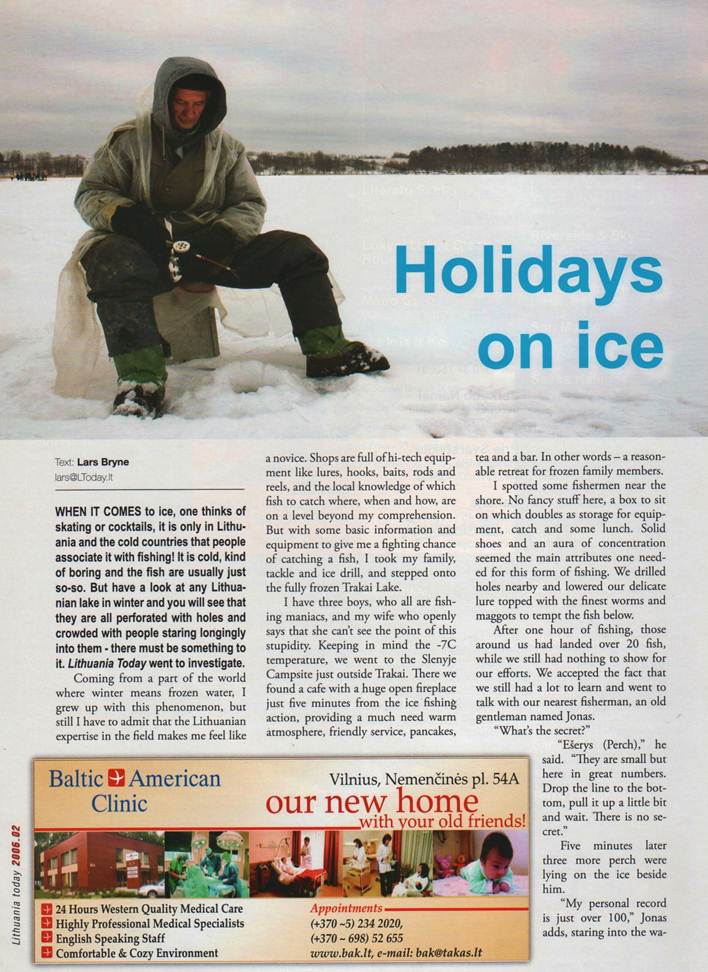

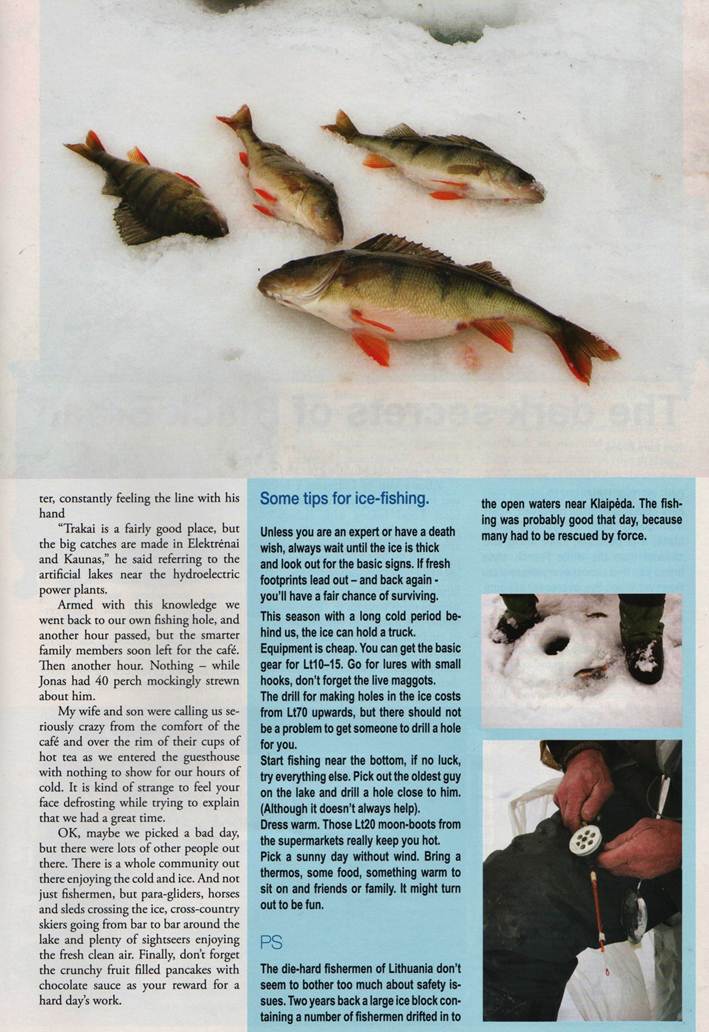

Holidays on ice

When it comes to ice, one thinks of skating or cocktails. It is only in Lithuania and other cold countries that people associate it with fishing!

It is cold, kind of boring and the fish are usually just so-so. But have a look at any Lithuanian lake in winter and you will see that they are all perforated with holes and crowded with people staring longingly into them – there must be something to it. Lars Bryne went to investigate.

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - (0) Comment

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - (0) Comment

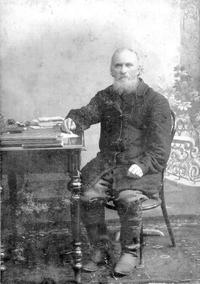

Jurgis Bielinis (1846-1918)

Lithuania’s book smugglers became a symbol of resistance to Russification

Jurgis Bielinis was one of the most famous Lithuanian book-smugglers. "Book smugglers (Lithuanian: knygnešys, or plural knygnešiai) were people who transported Lithuanian language books printed in the Latin alphabet into Lithuanian-speaking areas of the Russian Empire, defying a ban on such materials in force from 1866 to 1904. Opposing imperial Russian authorities' efforts to replace the traditional Latin orthography with Cyrillic, and transporting printed matter from as far away as the United States to do so, the book smugglers became a symbol of Lithuanians' resistance to Russification." (Wikipedia) Thank you for the post, National Lithuanian American Hall of Fame!

Boris Bakunas

__________________________

I forgot all about it till now. Thank you Boris Bakunas for this post

Irene Simanavicius

__________________________

The Lithuanians who helped save our language, our culture, and our history were remarkable people

With so much dirt slung around on the internet, I applaud the National Lithuanian American Hall of Fame for helping to inspire Lithuanians and people of Lithuanian descent with examples we can learn from.

Boris Bakunas

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - (0) Comment

|

IN MEMORY OF JEWISH KAUNAS |

Kaunas Ghetto (1941-1944):

An entire urban district turned into a merciless death camp

Two children in the Kaunas (Kovno) Ghetto, Lithuania.

Yad Vashem Photo Archive, 4789

What happened to the Jews in Lithuania during World War II is a matter of grim record. Of the 250.000 Jews in 1939, only between 12.500 and 17.500 survived; of those, only about 200 remain today.

It has been estimated that of the 265.000 Jews living in Lithuania in June 1941, 254.000 or 95% were murdered during the German occupation. No other Jewish community in Nazi-occupied Europe was so comprehensively destroyed.

The Red Army occupied Lithuania in June 1940, and the country remained under Soviet control until June 1941, when it fell to the invading German Army (Wehrmacht). On 8 July 1941 an order was issued stating that all Jews had to wear a special patch on their back; subsequently they were ordered to wear the patch on their chest. In addition Jews were forbidden to walk along the main streets of the city, and shops were ordered to sell them food in limited amounts. Jewish people were fired from their jobs, deprived of the means of personal transportation and radios, forbidden to use public transport, and prohibited from public places. Jews were arrested on the streets, at their work places, and in their houses.

The Kaunas (Kovno) Ghetto

Between 1920 and 1940, Kaunas (Kovno) was Lithuania's capital and largest city. It had a Jewish population of 35.000-40.000, about one-fourth of the city's total population. Jews were concentrated in the city's commercial, artisan, and professional sectors.

Kaunas was also a centre of Jewish learning. The yeshiva in Slobodka, an impoverished district of the city, was one of Europe's most prestigious institutions of higher Jewish learning, with a rich and varied Jewish culture. The city had almost 100 Jewish organizations, 40 synagogues, many Yiddish schools, 4 Hebrew high schools, a Jewish hospital, and scores of Jewish-owned businesses. It was also an important Zionist center.

Kaunas‘ Jewish life was disrupted when the Soviet Union occupied Lithuania in June 1940. The occupation was accompanied by arrests, confiscations, and the elimination of all free institutions. Jewish communal organizations disappeared almost overnight. Soviet authorities confiscated the property of many Jews. Meanwhile, the Lithuanian Activist Front, founded by Lithuanian nationalist emigres in Berlin, clandestinely disseminated antisemitic literature in Lithuania. Among other themes, the literature blamed Jews for the Soviet occupation. Hundreds of Jews were exiled to Siberia.

Following Germany's invasion of the Soviet Union on 22 June 1941, Soviet forces fled Kaunas. Immediately before and following the German occupation of the city on June 24, anti-Communist, pro-German Lithuanian mobs began to attack Jews (whom they unfairly blamed for Soviet repression), especially along Jurbarko and Krisciukaicio streets. These right-wing vigilantes murdered hundreds of Jews and took dozens more Jews to the Lietukis Garage, in the city center, and killed them there.

Moving into the Kovno Ghetto.

George Kadish, photographer, George Kadish, Florida.

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - (1) Comment

Kaunas Ghetto (1941-1944):

An entire urban district turned into a merciless death camp

Two children in the Kaunas (Kovno) Ghetto, Lithuania.

Yad Vashem Photo Archive, 4789

What happened to the Jews in Lithuania during World War II is a matter of grim record. Of the 250.000 Jews in 1939, only between 12.500 and 17.500 survived; of those, only about 200 remain today.

It has been estimated that of the 265.000 Jews living in Lithuania in June 1941, 254.000 or 95% were murdered during the German occupation. No other Jewish community in Nazi-occupied Europe was so comprehensively destroyed.

The Red Army occupied Lithuania in June 1940, and the country remained under Soviet control until June 1941, when it fell to the invading German Army (Wehrmacht). On 8 July 1941 an order was issued stating that all Jews had to wear a special patch on their back; subsequently they were ordered to wear the patch on their chest. In addition Jews were forbidden to walk along the main streets of the city, and shops were ordered to sell them food in limited amounts. Jewish people were fired from their jobs, deprived of the means of personal transportation and radios, forbidden to use public transport, and prohibited from public places. Jews were arrested on the streets, at their work places, and in their houses.

The Kaunas (Kovno) Ghetto

Between 1920 and 1940, Kaunas (Kovno) was Lithuania's capital and largest city. It had a Jewish population of 35.000-40.000, about one-fourth of the city's total population. Jews were concentrated in the city's commercial, artisan, and professional sectors.

Kaunas was also a centre of Jewish learning. The yeshiva in Slobodka, an impoverished district of the city, was one of Europe's most prestigious institutions of higher Jewish learning, with a rich and varied Jewish culture. The city had almost 100 Jewish organizations, 40 synagogues, many Yiddish schools, 4 Hebrew high schools, a Jewish hospital, and scores of Jewish-owned businesses. It was also an important Zionist center.

Kaunas‘ Jewish life was disrupted when the Soviet Union occupied Lithuania in June 1940. The occupation was accompanied by arrests, confiscations, and the elimination of all free institutions. Jewish communal organizations disappeared almost overnight. Soviet authorities confiscated the property of many Jews. Meanwhile, the Lithuanian Activist Front, founded by Lithuanian nationalist emigres in Berlin, clandestinely disseminated antisemitic literature in Lithuania. Among other themes, the literature blamed Jews for the Soviet occupation. Hundreds of Jews were exiled to Siberia.

Following Germany's invasion of the Soviet Union on 22 June 1941, Soviet forces fled Kaunas. Immediately before and following the German occupation of the city on June 24, anti-Communist, pro-German Lithuanian mobs began to attack Jews (whom they unfairly blamed for Soviet repression), especially along Jurbarko and Krisciukaicio streets. These right-wing vigilantes murdered hundreds of Jews and took dozens more Jews to the Lietukis Garage, in the city center, and killed them there.

Moving into the Kovno ghetto.

George Kadish, photographer, George Kadish, Florida.

Entrance gate to the Kaunas (Kovno) Ghetto (1941-1944).

Etching dated 1943, by Esther Lurie.

Street corner in the Kaunas Ghetto.

In early July 1941, German Einsatzgruppe (mobile killing unit) detachments and their Lithuanian auxiliaries began systematic massacres of Jews in several of the forts around Kaunas. These forts had been constructed by the Russian tsars in the nineteenth century for the defense of the city. Einsatzgruppe detachments and Lithuanian auxiliaries shot thousands of Jewish men, women, and children, primarily in the Ninth Fort, but also in the Fourth and Seventh forts. Within six months of the German occupation of the city, the Germans and their Lithuanian collaborators had murdered half of all Jews in Kaunas.

Ghetto street, November 1943.

Footbridge connecting the large and the small ghetto.

The Nazis established a civilian administration under SA Major General Hans Kramer. Between July and 15 August 1941, the Germans concentrated the remaining Jews, some 29.000 people, in a ghetto established in Slobodka. It was an area of small primitive houses and no running water. The ghetto had two parts, called the "small" and "large" ghetto, separated by Paneriu Street. In the autumn of 1943, the SS assumed control of the ghetto and converted it into the Kauen concentration camp. On 8 July 1944, the Germans evacuated the camp, deporting most of the remaining Jews to the Dachau concentration camp in Germany or to the Stutthof camp, near Danzig, on the Baltic coast. Three weeks before the Soviet army arrived in Kaunas, the German razed the ghetto to the ground with grenades and dynamite. As many as 2.000 people burned to death or were shot while trying to escape.

At its peak, the Ghetto held 40,000 people, most of whom were later sent to concentration and extermination camps, or were shot at the Ninth Fort. About 500 Jews escaped from work details and directly from the Ghetto, and joined Soviet partisan forces in the distant forests of southeast Lithuania and Belarus.

Youth in line for distribution of soup in the workers' kitchen in the Kaunas Ghetto.

The ghetto fire brigade with their chief Abramovitz (in front), August 1943.

Organization

The ghetto had two parts, called the "small" and "large" ghetto, separated by Paneriai Street and connected by a small wooden bridge over the street. Each ghetto was enclosed by barbed wire and closely guarded. Both were overcrowded, with each person allocated less than ten square feet of living space. The Germans continually reduced the ghetto's size, forcing Jews to relocate several times. The Germans and Lithuanians destroyed the small ghetto on October 4, 1941, and killed almost all of its inhabitants at the Ninth Fort. Later that same month, on 29 October 1941, the Germans staged what became known as the "Great Action." In a single day, they shot around 10,000 Jews at the Ninth Fort (see below).

The ghetto in Kovno provided forced labor for the German military. Jews were employed primarily as forced laborers at various sites outside the ghetto, especially in the construction of a military airbase in Aleksotas. The Jewish council (Aeltestenrat; Council of Elders), headed by Dr. Elkhanan Elkes, also created workshops inside the ghetto for those women, children, and elderly who could not participate in the labor brigades. Eventually, these workshops employed almost 6,500 people. The council hoped the Germans would not kill Jews who were producing for the army.

Jewish workers on their way back to the Ghetto after a day of forced labour.

|

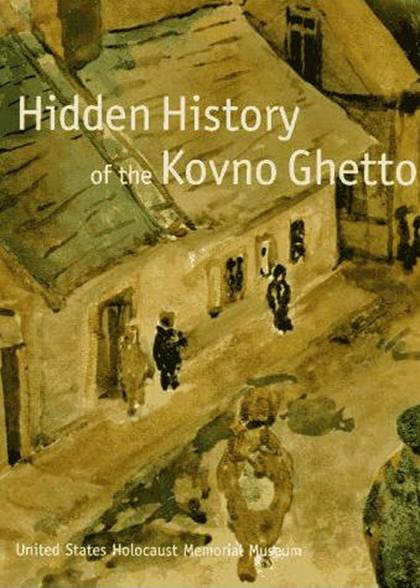

The Underground School As an act of defiance an underground school was conducted in the Kovno Ghetto when such education was banned in 1942. A remarkable photo of one of the classes of that school features in the US Holocaust publication, "The Hidden History of the Kovno Ghetto". Identification of the teacher visible in that photo is given in a website that deals with the hidden school. However almost all of the children in the Ghetto, approximately 2,500, were removed in the Kinder Aktion of 27–28 March 1944. |

|

Unidentified child in the Kaunas Ghetto, 1943.

www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/jsource/Holocaust/finkelsteinkovno.html

Smuggling Babies out of the Ghetto

From 1942 births were not permitted in the ghetto and pregnant women faced death. However a number of babies of ages from about 9 months to 15 months were smuggled out of the Kovno Ghetto to willing Lithuanian foster mothers.

Final days

In the autumn of 1943, the SS assumed control of the ghetto and converted it into the Kovno concentration camp. The Jewish council's role was drastically curtailed. The Nazis dispersed more than 3,500 Jews to subcamps where strict discipline governed all aspects of daily life. On October 26, 1943, the SS deported more than 2,700 people from the main camp. The SS sent those deemed fit to work to Vaivara concentration camp in Estonia, and deported surviving children and the elderly to Auschwitz.

On 8 July 1944, the Germans evacuated the camp, deporting most of the remaining Jews to the Dachau concentration camp in Germany or to the Stutthof camp, near Danzig, on the Baltic coast. Three weeks before the Soviet army arrived in Kovno, the Germans razed the ghetto to the ground with grenades and dynamite. As many as 2,000 people burned to death or were shot while trying to escape the burning ghetto. The Red Army occupied Kaunas on 1 August 1944. Of Kaunas‘ few Jewish survivors, 500 had survived in forests or in a single bunker which had escaped detection during the final liquidation; the Germans evacuated an additional 2,500 to concentration camps in Germany.

Jewish women standby murdered corpses outside

the Seventh Fort in Kaunas.

Resistance

Throughout the years of hardship and horror, the Jewish community in Kaunas documented its story in secret archives, diaries, drawings and photographs. Many of these artifacts lay buried in the ground when the ghetto was destroyed. Discovered after the war, these few written remnants of a once thriving community provide evidence of the Jewish community's defiance, oppression, resistance, and death. George Kadish (Hirsh Kadushin), for example, secretly photographed the trials of daily life within the ghetto with a hidden camera through the buttonhole of his overcoat.

Monument of the Kaunas Ghetto

The Kovno ghetto had several Jewish resistance groups. The resistance acquired arms, developed secret training areas in the ghetto, and established contact with Soviet partisans in the forests around Kaunas.

In 1943, the General Jewish Fighting Organization (Yidishe Algemeyne Kamfs Organizatsye) was established, uniting the major resistance groups in the ghetto. Under this organization's direction, some 300 ghetto fighters escaped from the Kovno ghetto to join Jewish partisan groups. About 70 died in action.

The Jewish council in Kaunas actively supported the ghetto underground. Moreover, a number of the ghetto's Jewish police participated in resistance activities. The Germans executed 34 members of the Jewish police for refusing to reveal specially constructed hiding places used by Jews in the ghetto.

The completely destroyed Kaunas Ghetto. In July 1944, the Germans blew up and

burned down the ghetto in search of Jews in hiding there.

Read more…

http://www.ushmm.org/museum/exhibit/online/kovno/intro/intro.htm

http://www.ushmm.org/wlc/en/article.php?ModuleId=10005174

http://www.holocaustresearchproject.org/ghettos/kovno.html

http://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/jsource/Holocaust/kovnotoc.html

http://www.fold3.com/page/286123943_the_kovno_ghetto_partisans_chaim_yelin/

http://www.lithuanianjews.org.il/HTMLs/article_list4.aspx?C2014=14287&BSP=14432&BSS59=14432

http://www.aish.com/ho/p/48949791.html

Books:

http://jewishhistoryaustralia.net/TheHistoryOfNow/Kovno/resource.php

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - (0) Comment

Kaunas massacre of 29 October 1941

The largest mass murder

of Lithuanian Jews

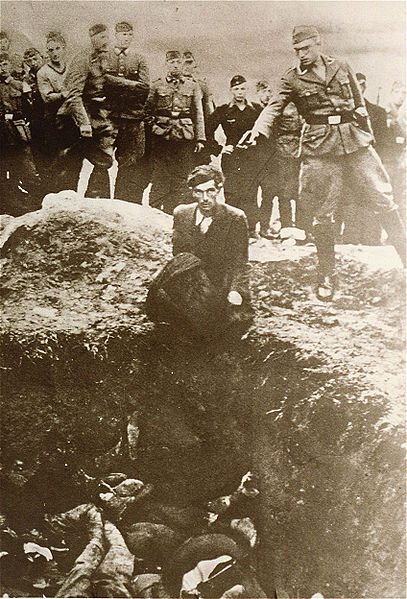

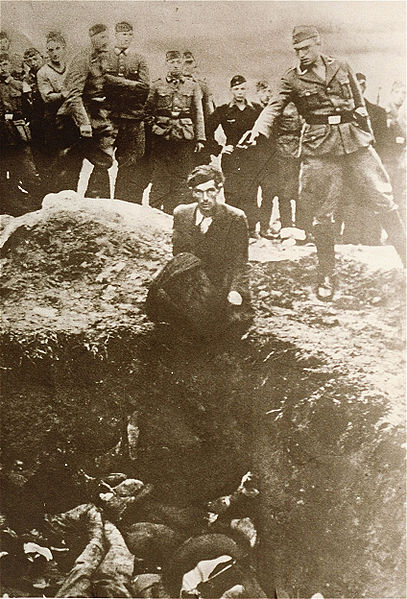

Thousands of Jews were killed to fall in pits like these.

Kaunas massacre of 29 October 1941, also known as the Great Action, was the largest mass murder of Lithuanian Jews.

By the order of SS-Standartenführer Karl Jäger and SS-Rottenführer Helmut Rauca, the Sonderkommando under the leadership of SS-Obersturmführer Joachim Hamann, and 8 to 10 men from Einsatzkommando 3, in collaboration with Lithuanian henchmen, murdered 2,007 Jewish men, 2,920 women, and 4,273 children in a single day at the Ninth Fort, Kaunas, Lithuania.

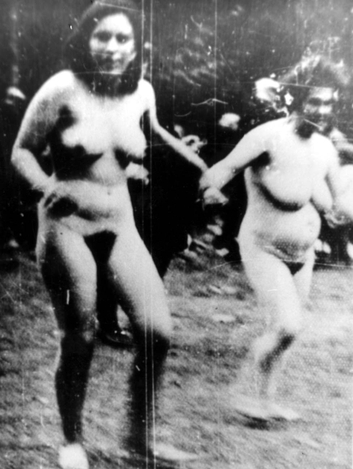

With the arrival of the SS Einsatzgruppen, the 'Great Action' began on October 28th. The Jewish inhabitants of the Ghetto were assembled on Democrats Square and all those fit for work were allowed back into the Ghetto. The others, over 9,000 men, women and children were marched to the SS execution centre in the Ninth Fort and there, stripped of their clothes and in the freezing cold, they awaited their fate. In groups of 200, they were stood on the edge of large pits, dug previously by Russian P.O.W.s, and were systematically machine-gunned to death.

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - (3) Comment

Kaunas massacre of 29 October 1941

The largest mass murder

of Lithuanian Jews

Thousands of Jews were killed to fall in pits like these.

Kaunas massacre of 29 October 1941, also known as the Great Action, was the largest mass murder of Lithuanian Jews.

By the order of SS-Standartenführer Karl Jäger and SS-Rottenführer Helmut Rauca, the Sonderkommando under the leadership of SS-Obersturmführer Joachim Hamann, and 8 to 10 men from Einsatzkommando 3, in collaboration with Lithuanian henchmen, murdered 2,007 Jewish men, 2,920 women, and 4,273 children in a single day at the Ninth Fort, Kaunas, Lithuania.

With the arrival of the SS Einsatzgruppen, the 'Great Action' began on October 28th. The Jewish inhabitants of the Ghetto were assembled on Democrats Square and all those fit for work were allowed back into the Ghetto. The others, over 9,000 men, women and children were marched to the SS execution centre in the Ninth Fort and there, stripped of their clothes and in the freezing cold, they awaited their fate. In groups of 200, they were stood on the edge of large pits, dug previously by Russian P.O.W.s, and were systematically machine-gunned to death.

These mass graves were later re-opened and all the bodies burned in an attempt to conceal the crime. This work was done by 72 men and women from the ghetto. While working, the prisoners were chained together to prevent escapes but all were later put to death when their work was finished.

In July, 1944, the Ghetto was burned down, blown apart and completely destroyed. The Germans and Lithuanians destroyed the small ghetto on October 4, 1941, and killed almost all of its inhabitants at the Ninth Fort. Later that same month, on October 28, SS-Rottenführer Helmut Rauca of the Kaunas Gestapo (secret state police) conducted the selection in the Kaunas Ghetto. All ghetto inhabitants were forced to assemble in a central square of the ghetto. Rauca selected 9,200 Jewish men, women, and children, about one-third of the ghetto population. The next day, 29 October, they shot these people at the Ninth Fort in huge pits dug in advance.

Jewish women, minutes before they are murdered by the

SS and their Lithuanian henchmen, Kaunas 1941.

KAUNAS’ NINTH FORT

At the end of 19th century, the city of Kaunas was fortified, and by 1890 it was encircled by eight forts and nine gun batteries. The construction of the Ninth Fort (its numerical designation having stuck as a proper noun) began in 1902 and was completed on the eve of World War I. From 1924 on, the Ninth Fort was used as the Kaunas City prison.

During the years of Soviet occupation, 1940-1941, the Ninth Fort was used by the NKVD to house political prisoners on their way to the labour camps in Siberia.

During the years of Nazi occupation, the Ninth Fort was put to use as a place of mass murder. At least 10,000 Jews, most of Kaunas, largely taken from the Kovno Ghetto, were transported to the Ninth Fort and killed by Nazis with the collaboration of some Lithuanians in what became known as the Kaunas massacre.

Notable among the victims was Rabbi Elchonon Wasserman of Baranovitch. In addition, Jews from as far as France, Austria and Germany were brought to Kaunas during the course of Nazi occupation and executed in the Ninth Fort. On 1943 the Germans operated special Jewish squads to open the massgraves and burn the remaining corpses. Such squad of 62 people managed to escape the fortress on the eve of 1944. In 1944, as the Soviets moved in, the Germans liquidated the ghetto and what had by then come to be known as the "Fort of Death", and the prisoners were dispersed to other camps. After World War II, the Soviets again used the Ninth Fort as a prison for several years. From 1948 to 1958, farm organizations were run out of the Ninth Fort.

In 1958, a museum was established in the Ninth Fort. In 1959, a first exposition was prepared in four cells telling about Nazi war crimes carried out in Lithuania. In 1960, the discovery, cataloguing, and forensic investigation of local mass murder sites began in an effort to gain knowledge regarding the scope of these crimes.

Through this door, 64 prisoners escaped on 25 December 1943.

TODAY A MUSEUM

The Ninth Fort museum contains collections of historical artifacts related both to Soviet atrocities and the Nazi genocide, as well as materials related to the earlier history of Kaunas and Ninth Fort.

The memorial to the victims of Nazism at the Ninth Fort in Kaunas, Lithuania, was designed by sculptor A. Ambraziunas. Erected in 1984, the monument is 105 feet (32 m) high. The mass burial place of the victims of the massacres carried out in the fort is a grass field, marked by a simple yet frankly worded memorial written in several languages. It reads, "This is the place where Nazis and their assistants killed more than 30,000 Jews from Lithuania and other European countries."

On April 11, 2011, the memorial to the victims of Nazism was vandalized - The memorial tombstones were knocked down, and white swastikas were sprayed on the memorial. On the adjacent sidewalk, the words “Juden raus” (German: Jews Out) were inscribed.

Kaunas – A sign saying “Jews out” and “Hitler was right” (Juden raus“„Hitleris buvo teisus“)

were hung in front of the synagogue on April 20th 2011, Hitler's day of birth.

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - (0) Comment

How I escaped from

How I escaped from

the Kaunas Ghetto

My coffee chat with Irena Veisaite (84) started here in the kitchen of her

cosy apartment in the outskirts of Vilnius Old Town. What a life story

hasn’t this gentle lady got to tell...

Text/photos: Aage Myhre

A room full of books. A desk covered with pamphlets, documents, newspaper clippings. Walls and bookshelves overcrowded with framed photographs of friends and relatives. Her today’s home in Vilnius is filled with warmth and wisdom.

Was this the way they lived? The Lithuanian Jews, often named as the Litvaks. Before the World War II horrific events so brutally took them and their culture here in Lithuania away forever? Or perhaps not forever?

Because here she lives, Irena Veisaite, born in this country in 1928. She is one of the few Litvaks who survived the Holocaust in Lithuania. A living evidence of cruelty and injustice. Yet with less bitterness and anger than you might think.

"Love," she says, "love is so much more important than hatred. Hatred is the most destructive feature that humanity possesses and even in the most difficult times I experienced a lot of kindness".

Irena was born in 1928 in Kaunas, the inter-war Lithuanian capital when Vilnius and the south-western part of the country was occupied by Poland. Her parents had a liberal European education and she grew up, as she describes, surrounded by very different people. She was playing with the neighbourhood children and never thought much of what nationality the other kids were. It was only when rumours of a potential war grew in strength that she began to feel a certain degree of insecurity.

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - (0) Comment

Abraham Sutzkever (1913-2010)

Poetry translation contest to be introduced at this year’s Summer Literary Seminars in Lithuania

Summer Literary Seminars has announced its Abraham Sutzkever Translation Prize, marking the centennial of the birth of one of the most acclaimed Yiddish poets of the 20th century.

“To me, he is the leading Yiddish poet, the epitome of Yiddish literature in the 20th century,” Mikhail Iossel said of Sutzkever. Iossel, a Soviet émigré and associate professor of English and Creative Writing at Concordia University in Montreal, is the founder and director of the literary, creative writing and historical workshops that have taken place in St. Petersburg, Montreal, Nairobi and Vilnius. The Sutzkever Prize is associated with the SLS Lithuania program for summer 2013.

The new prize is being added to a lineup of already existing ones that are given through the SLS Unified Literary Contest, awarding winners with tuition, stipends and publication assurances. The winner of the Sutzkever Prize will receive tuition to SLS Lithuania plus $500 toward travel expenses. In addition, the winning entry will be translated into Lithuanian, and read at a celebration in Vilnius on the centennial, on July 15, 2013. The deadline for submissions is February 28, 2013.

READ MORE…

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - (0) Comment

A poem by Abraham Sutzkever

How?

How will you fill your goblet

On the day of liberation? And with what?

Are you prepared, in your joy, to endure

The dark keeing you have heard

Where skulls of days glitter

In a bottomless pit?

You will search for a key to fit

You jammed locks. You will bite

The sidewalks like bread,

Thinking: It used to be better.

And time will gnaw at you like a cricket

Caught in a fist.

Then your memory will resemble

And ancient buried town

And your estranged eyes will burrow down

Like a mole, a mole….

Vilna Ghetto, February 14, 1943

Translated by Chana Bloch

SESSION 2: 27 July – 10 Aug

http://sumlitsem.org/Lithuania/

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - (7) Comment

How I escaped from

How I escaped from

the Kaunas Ghetto

My coffee chat with Irena Veisaite (84) started here in the kitchen of her cosy apartment in the outskirts of

Vilnius Old Town. What a life story hasn’t this gentle lady got to tell...

Text/photos: Aage Myhre

A room full of books. A desk covered with pamphlets, documents, newspaper clippings. Walls and bookshelves overcrowded with framed photographs of friends and relatives. Her today’s home in Vilnius is filled with warmth and wisdom. Was this the way they lived? The Lithuanian Jews, often named as the Litvaks. Before the World War II horrific events so brutally took them and their culture here in Lithuania away forever? Or perhaps not forever? Because here she lives, Irena Veisaite, born in this country in 1928. She is one of the few Litvaks who survived the Holocaust in Lithuania. A living evidence of cruelty and injustice. Yet with less bitterness and anger than you might think.

"Love," she says, "love is so much more important than hatred. Hatred is the most destructive feature that humanity possesses and even in the most difficult times I experienced a lot of kindness".

Irena was born in 1928 in Kaunas, the inter-war Lithuanian capital when Vilnius and the south-western part of the country was occupied by Poland. Her parents had a liberal European education and she grew up, as she describes, surrounded by very different people. She was playing with the neighbourhood children and never thought much of what nationality the other kids were. It was only when rumours of a potential war grew in strength that she began to feel a certain degree of insecurity.

"But," she says," my biggest fear in the early 1930's was that my parents would divorce. Not the potential war."

She also remembers with great pleasure that the house her father built in Kaunas in 1936 was named as Lithuania's top residential housing. However, insecurity began to make itself increasingly evident in the late thirties. More and more often her parents whispered among themselves. About Adolph Hitler. About growing fears of war. Eight-year-old Irena began to experience painful nightmares. She would often wake up at night because of frightening dreams of a deadly despot, a man who was now leading a country that she and her family had so many good memories about, a country named Germany.

"I learned a new phrase when I was eight years old," she tells me while we sit in her book-crowded apartment in Vilnius this early February day. "The word was 'Anti Semitism'. “But what this word really meant I understood only much later.”

Irena stands in her kitchen, making coffee for me while she talks about those first, painful childhood experiences.

"Unfortunately my greatest childhood fears came true when I was 10 years old and my parents decided to divorce. The agreement was that I should stay with my mother in Kaunas during the year but spend the summer vacations with my father. In the summer of 1938 my father took me on a wonderful European trip. We travelled through Berlin to Switzerland, Belgium and France”

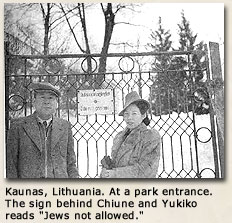

"It is very vivid in my memory how we walked along Berlin's famous street, Unter den Linden, and saw the yellow benches which were different from all others, meant only for the Jews. As foreigners, we could have sat down on any bench, but my father insisted that we should sit on a yellow bench out of solidarity with the German Jews and to get the feeling of what it meant to be excluded."

|

In German city parks by the end of the 1930s, there were yellow benches bearing the logo “for Jews only.” Jews were not permitted to sit on any other park benches nor use public transportation or drive a car. These measures made it easy to identify the stigmatized Jews so that they could then be transported to ghettos in the East and finally carted to their deaths in concentration camps such as Sobibor, Auschwitz, Neuengamme, Buchenwald etc. |

|

In 1939, Hitler's war machinery started to roll east. The infamous Molotov-Ribbentrop pact was signed that year, and it soon became clear that little Lithuania was about to be squeezed between two superpowers that were not to show any mercy to the Lithuanian people.

The Soviet Union's first WWII occupation of Lithuania took place in 1940. One year later they were driven back by the German troops and the country was suddenly under German domination. While the Soviet occupation was infinitely tragic for the ethnic Lithuanians, due to the memory of the Tsarist Russia's occupation of the country from late 1700's until well into the First World War and especially the deportations of the 14 June 1941, the Nazi occupation may have appeared as liberation from the Soviet dictatorship.

For the Jews deportation to Siberia was still a chance to survive, while the devastating Nazi occupation meant certain death. Jews and Lithuanians, who had lived in peace and harmony side by side for hundreds of years, became involuntary victims of a war none of them wanted.

Irena recalls the outbreak of the war as a very dark time. She remembers the overpowering Nazi propaganda which identified all the Jews with Communists who betrayed their homeland - Lithuania - to the Soviet Union. The Jews were apportioned the blame for carrying out the deportations of the Lithuanians to Siberia without any mention of the fact that many Jews were also deported. The mood of hatred and retaliation escalated, there were pogroms in Kaunas. Jewish people were arrested and shot in the streets.

Just a few days after the German occupation in June of 1941, Irena's mother was arrested in hospital where she was recovering after major kidney surgery. She was taken to a prison and it is estimated that she was executed in mid-July. 13-year old Irena became motherless in an unimaginably tragic way.

Irena's voice trembles when she talks about her Mother and what happened that July day.

After the brutal murder, Irena remained alone because her father then lived in Belgium (where he survived the war). They had no contact anymore.

During the war years that followed, there was substantial cooperation and collaboration between the German forces and some Lithuanians. The Lithuanian Activist Front volunteer police force, known as Tautinio Darbo Apsaugos Batalionas (TDA), that was hoping to be transformed into a regular army of independent Lithuania, became instead employed by the Germans as auxiliary in massacres of the Jews during the Holocaust that led to the tragic destruction of around 200 000 Jews, about 90- 95% of the country’s pre-war Jewish population.

In August 1941 all the Kaunas Jews were imprisoned in the ghetto which was located in the Kaunas suburb Vilijampole. Irena stayed in the ghetto with her grandparents and one aunt.

The 7th of November 1943 is a date Irena will never forget. Lithuanian friends of her parents, the Strimaitis family, had managed to convey a message to her in the ghetto, saying that she should follow one of the labour brigades out of the ghetto to the work place in town. They also had procured false documents for her. An agreement was reached with a Jewish policeman who was responsible for the list of workers that she should not be included on the list that day, but still follow the group out and then try to escape unnoticed into a side street as soon as they passed the ghetto gates. The moment of stepping out of the column of Jewish workers was the most horrifying and dangerous one in young Irena's life. But fortunately she made it without being detected.

Kaunas Ghetto street, November 1943.

She managed to get off the yellow stars that all Jews were obliged to bear on both the chest and back, and went unnoticed to the agreed meeting point on the Viljampole bridge across river Neris. The work brigade had been more than an hour late out of the ghetto that day, and her family friends had already gone home when Irena came to the meeting place, so she had to find her way alone, walking through the centre of town.

Irena knew the address to the Strimaitis family and managed to find their house in the centre of Kaunas. What she did not know was the number of their apartment, so she found herself ringing the caretaker's door bell. Both she and her friends knew, however, that caretakers were among the most eager informers for the Gestapo, and her contact with the caretaker made the friends so nervous that none of them could sleep that night.

Early next morning they travelled to Vilnius, hoping that the caretaker had not been able or wanted to alert the Gestapo. Irena's Lithuanian was luckily very good, so it was also possible that the caretaker had not realized that she was Jewish.

The Strimaitis family continued to take care of Irena and found a few places for her to stay in Vilnius. Finally, in March 1944, she was taken into a home of Stefanija Ladigiene who took her into her family and became her ‘second mother’. She stayed with this family also after the war had ended because she had no one else left. All her friends and family had perished in the Holocaust.

As Irena had identification papers (false, though) she was able to take a job. Marcele Kubiliute, a friend of the Strimaitis family, found her a job at an orphanage in Vilnius Old Town, where she worked in the laundry and as a cleaner until the summer of 1944.

When the Soviets re-occupied Lithuania the summer of 1944, Irena desperately wanted to rebuild her life. She entered a Lithuanian high school in Vilnius which she finished in record speed, taking only three years instead of the usual five, to get her final exam papers. She then applied to Vilnius University to study Lithuanian Language and Literature. Unfortunately at this time the KGB was after Irena and wanted to enlist her as an informant, to which she would never agree. Her ‘second mother’ was arrested in March 1946, and there was another complication: Irena's father lived abroad and was classified as a bourgeois, and for this reason she was in danger of being expelled from the University. With the help of her relatives in Moscow she left Vilnius and continued her education in Moscow, studying German language and literature.

In 1953, having graduated from the Moscow Lomonosov State University, Irena came back to Vilnius, determined to work in Lithuania. She became a lecturer at the Pedagogical University in Vilnius, where she taught the history of Western European and German literature. She later taught at other universities, and became involved in theatre and many other activities, although the pedagogical university remained her main employer, through 43 relatively good, happy years.

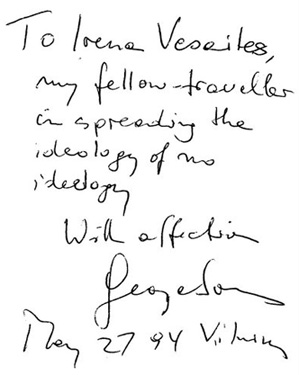

Soon after Lithuania's new process of liberation, in 1990, Irena, together with Professor Ceslovas Kudaba was invited by the philanthropist and billionaire George Soros to create the Open Society Fund in Lithuania.

"I was happy to accept the offer. I felt like I was getting new wings because this gave me the possibility to do on a much bigger scale what I was trying to do all my life - stimulating critical and creative thinking and bringing Lithuania back to Europe and basic European human values... To show an alternative to Soviet thinking. I accepted his invitation to lead the Fund for the years 1990-2000."

Today Irena is still working with George Soros and his Open Society Fund, and now acts as Ombudsman for his worldwide organization.

|

|

To Irena Veisaite, With affection

|

In spite of her tragic past Irena leads a very active life. She is appreciated for her positive thinking and tolerance, and was in 2002 awarded the prestigious title; "Person of Tolerance in Lithuania.” Irena is not affected by hatred or revenge.

As she puts it to me; “I do not remember the faces of any evil people from my past, but I do very well remember the faces of those that expressed goodness. We have to learn to love and to understand..."

Dr. Irena Veisaite (84) at her study desk in Vilnius, Lithuania.

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - (0) Comment

|

IN MEMORY OF JEWISH KAUNAS |

Chiune Sugihara:

The Japanese diplomat/

spy who became a hero of the Holocaust

By Boris Bakunas, PhD

In the Year of Shame 1940, while the bulk of the German military machine was consolidating its grip on Poland, 110 French and British divisions sat idly on the Western Front, facing a token German force a fraction its size.

In the Year of Shame 1940, the People’s Commissariat for Internal Affairs, the dreaded NKVD, massacred 22,000 captured members of the Polish Officer Corps, turning the Katyn Forest into a vast mass grave.

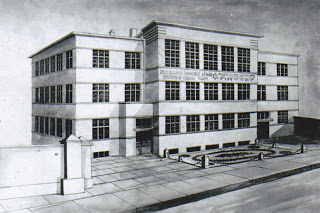

In that same Year of Shame 1940, Chiune Sugihara, a Japanese diplomat and spy stationed in Kaunas, Lithuania – along with his wife Yukiko – made a joint decision in defiance of direct orders from their government, and together they lit a beacon of hope for thousands of Polish and Lithuanian Jews. From 19 July to 28 August, 1940, the two-storey, white stucco building on 30 Vaizgantas Street that housed the Japanese Consulate, became the moral capital of the world.

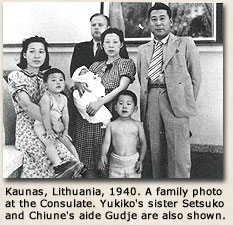

Chiune and Yukiko Sugihara with their two children had arrived in Kaunas from Helsinki in 1939 not long after Nazi and Soviet troops sliced Poland into two zones of terror. Chiune’s ostensible mission was to serve as the Japanese Vice-Consul in Kaunas. His real assignment was to gather intelligence on the strength of the Soviet military in the West.

But a chance encounter at a delicatessen with an eleven-year-old Lithuanian-Jewish boy named Solly Ganor intervened, transforming the suave foreign-service officer renowned in diplomatic circles for throwing lavish parties into a hero of the Holocaust.

Jewish refugees at the gate of the Japanese Consulate in Kaunas,

July 1940. Thousands of Jews lined up here, hoping to receive transit visas allowing them to escape to the Far East and to America or Palestine.

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - (11) Comment

|

IN MEMORY OF JEWISH KAUNAS |

Chiune Sugihara:

The Japanese diplomat/

spy who became a hero of the Holocaust

By Boris Bakunas, PhD

In the Year of Shame 1940, while the bulk of the German military machine was consolidating its grip on Poland, 110 French and British divisions sat idly on the Western Front, facing a token German force a fraction its size.

In the Year of Shame 1940, the People’s Commissariat for Internal Affairs, the dreaded NKVD, massacred 22,000 captured members of the Polish Officer Corps, turning the Katyn Forest into a vast mass grave.

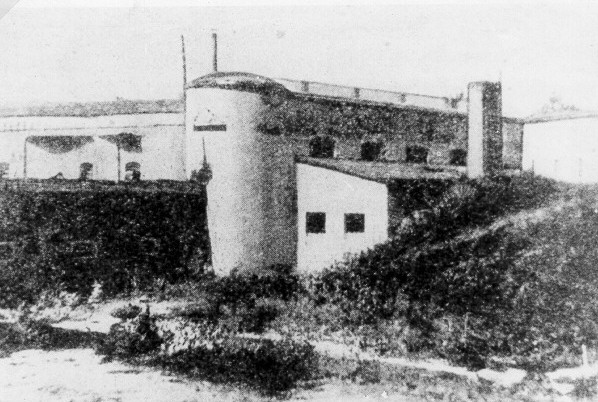

In that same Year of Shame 1940, Chiune Sugihara, a Japanese diplomat and spy stationed in Kaunas, Lithuania – along with his wife Yukiko – made a joint decision in defiance of direct orders from their government, and together they lit a beacon of hope for thousands of Polish and Lithuanian Jews. From 19 July to 28 August, 1940, the two-storey, white stucco building on 30 Vaizgantas Street that housed the Japanese Consulate, became the moral capital of the world.

Chiune and Yukiko Sugihara with their two children had arrived in Kaunas from Helsinki in 1939 not long after Nazi and Soviet troops sliced Poland into two zones of terror. Chiune’s ostensible mission was to serve as the Japanese Vice-Consul in Kaunas. His real assignment was to gather intelligence on the strength of the Soviet military in the West.

But a chance encounter at a delicatessen with an eleven-year-old Lithuanian-Jewish boy named Solly Ganor intervened, transforming the suave foreign-service officer renowned in diplomatic circles for throwing lavish parties into a hero of the Holocaust.

Jewish

refugees at the gate of the Japanese Consulate in Kaunas, July 1940.

Thousands

of Jews lined up here, hoping to receive transit visas allowing

them

to escape to the Far East and to America or Palestine.

“Now is the time to leave.”

Years later, an elderly, but healthy Solly Ganor recalled that fateful encounter.

As Solly, his hair flaked with snow, stepped through the door of his Aunt Anushka’s delicatessen in Kaunas, he saw her chatting amiably with “an elegantly-dressed man with strange, slanting eyes.”

“Ah, my dear nephew has come for his Hanukah money,” Aunt Anushka exclaimed. “Come here and meet his Excellency, the Consul of Japan, Mr. Sugihara.”

“How do you do, Sir?” Solly said.

The man shook Solly’s hand and smiled. Solly remembers taking an immediate liking to him. “There was humor and kindness in those strange eyes,” he later recalled.

Aunt Aunushka said to Solly, “You want to go to the movies, and you need a litas, right?” Solly nodded eagerly.

But before Aunt Anushka could get to the cash register, Mr. Sugihara reached into his pocket and handed Solly a shiny coin. “Since this is Hanukah, consider me your uncle.”

Solly hesitated. Then he impulsively blurted out an invitation. “Since you are my uncle, then you should come Saturday to our Hanukah party. The whole family will be there.”

The arrangements made, Solly went off to see a Laurel and Hardy film.

At six, Aunt Anushka arrived with Mr. and Mrs.Sugihara and Yukiko’s sister Setsuko at the Ganors’ apartment. Solly recalled that Mr. Sugihara wore a striped suit. His wife Yukiko, was dressed in an elegant black dress.

The Ganors had lived in Kaunas for generations. Solly’s father Chaim was a successful businessman. Among the many guests were two refugees from Warsaw, Mr. Rosenblatt and his little daughter, Lea.

The family and guests sat down at the long dinner table. Yukiko had never seen such a huge meal. There was even a duck, Japanese-style, which Aunt Anushka had specially prepared.

Mr. and Mrs.Sugihara attentively watched the Hanukkah rituals. Solly noticed that Mr. Sugihara was particularly interested in the story of Judah Maccabee, the leader of a successful Jewish revolt against foreign invaders in the second century B.C.E. He asked many questions about it.

Later, Mr. Sugihara asked Solly about his hobbies. When he learned that stamp collecting was one of them, he invited Solly to the consulate to see some Japanese stamps.

After dinner, Mr. Rosenblatt described his narrow escape from Poland and the things he had witnessed: his wife’s death during the bombings of Warsaw, Jews terrorized by Nazis and anti-Semites, arrested, and shipped off to camps. As he recounted the atrocities, Mr. Rosenblatt started to cry.

“It was painful to hear those horrible stories,” Solly recalled. “But Sugihara listened to every word.”

Later Solly overheard Mr. Rosenblatt pleading with Mr. Sugihara to issue him a visa so he could leave Kaunas. “Even a transit visa will help.”

Mr. Sugihara told Mr. Rosenblatt to come see him.

One day after school, Solly visited the consulate. Mr. Sugihara showed him into his office and pulled out an envelope from his desk drawer containing Japanese stamps. After showing him the stamps, Mr. Sugihara asked Solly a series of questions.

Had Mr. Rosenblatt and his daughter gotten their transit visas yet? How was Solly’s family faring? Solly knew that his father was hesitant about selling the family business. He couldn’t imagine Hitler invading Lithuania with Soviet troops in the country.

Mr. Sugihara’s voice suddenly sounded serious. Would Solly give his father an important message? Solly nodded. Mr. Sugihara spoke very quietly, as if he were telling a secret. “The time to leave is now,” he said.

|

|

|

|

“They all looked so sad.”

On the morning of July 27, 1940, as was his custom, Chiune rose early, ate breakfast, and climbed down the stairs to consular office below. What he saw outside his window caused him to rush back upstairs to show Yukiko.

Instead of the tranquil tree-lined street, she saw a crowd of about two hundred people, many of them dressed in bedraggled clothes.

“There were children, women, and young men,” Yukiko later said. “They were all hanging onto the fence. The young men were trying to climb over the fence. But the security of the consulate was pushing them back.”

Yukiko took several photographs. “They all looked so sad. Some women were looking right at me with great sorrow.”

To calm the throng, Chiune Sugihara agreed to meet with a delegation of five in his office. Zorach Warhaftig, a leader of Poland’s religious Zionists, was selected as head of the group. One by one the delegates described the terrible plight of the Jews. Mr. Warhaftig also told Mr. Sugihara that the Dutch consul had agreed to give Jewish refugees entrance visas for the Dutch Caribbean island of Curacao. But to get there, they would have to travel to Japan first. Would Mr. Sugihara issue transit visas for Japan?

Mr. Sugihara expressed his deep sympathy. However, he could issue only a few visas on his own authority. He told the Jewish delegates that he needed time to think. He asked them to come back the next day.

That night Chiune and Yukiko tossed and turned in a restless half-sleep. In the morning, they saw that the crowd had grown. Entire families were now sleeping on the ground, afraid that they might lose their place in line.

When Sugihara met with the Jewish delegates, the acting Dutch consul, Mr. Jan Zwartendijk, was also present.

Mr. Zwartendijk affirmed that he was willing to do all he could to help. Everybody now looked at Mr. Sugihara. Looking them straight in the eyes, Mr. Sugihara announced that he was willing to cable the Japanese Foreign Ministry for permission to grant transit visas, provided that his wife agreed.

The meeting adjourned. The first spark of hope had been struck. What had begun as a chance meeting between an eleven-year-old boy and a Japanese Consul was fast turning into a conspiracy.

Chiune

Sugihara with his wife Yukiko

“This request is a humanitarian plea.”

That evening Chiune and Yukiko descended the stairs to the consular office, where Chiune began the laborious process of encoding a cable to the Foreign Ministry. Yukiko transcribed the cable in triplicate by hand.

“I request permission to issue visas to hundreds of Jewish people who have come to the consulate here in Kaunas seeking transit visas. They are suffering terribly. As a fellow human being, I cannot refuse their requests. Please permit me to issue visas to them. This request is a humanitarian plea. The refugees’ request for visas should not be denied.”

Two days later, Chiune Sugihara decoded a cable from Japan. His urgent plea had been emphatically denied. The denial ended with the words. “No exceptions. STOP. No further inquiries expected. STOP. K. Tanaka, Foreign Ministry Tokyo.”

Undaunted, Sugihara sent a second request. The crowd of refugees, many with faces ashen from hunger and fatigue, continued to grow.

A second cable from Tokyo arrived. “Permission denied.”

Sugihara tried a third and final time. DENIED!

Wearily he went upstairs to share the bad news with Yukiko. They both knew they faced a grim, and possibly deadly choice.

If Chiune defied the Foreign Ministry’s orders, at the very least, his career would be ruined. At worst, he would be placing his life and the lives of his wife and children in peril. As Yukiko later said, “If we were in Germany, and we did something like that, my husband, myself, my children could all be taken away by the Nazis. I didn’t know what they would do to us. Maybe they’d kill us.”

Chiune looked into Yukiko’s eyes and told her that he had decided to issue visas under his own authority. Did she approve? Yes.

The next day, Chiune Sugihara had his chauffer drive him to the Soviet Embassy where he met with the Soviet consul. Sugihara spoke fluent Russian. After a brief period of negotiation, the Soviet consul agreed to allow the refugees to travel across the Soviet Union via to trans-Siberian railroad to ports along the Pacific coast where they could board ships for Japan, but at five times the standard price.

As the shiny black Buick with the Japanese flag slowly drove past the refugees outside the consulate, all eyes were trying to gauge the look on the diplomat’s face. But they saw no hint of what had transpired. The tension in the crowd grew.

Finally, Mr. Suhigara stepped out of the building and stood in front of the gate. In a calm, authoritative voice, he announced that he would issue a visa to every man, woman, and child. After a moment of stunned silence, the crowd erupted in cries of joy. Families and friends hugged and kissed.

Sugihara interviewed each refugee, asking probing questions in an attempt to find useful details to write on the visas. Each visa had to be written by hand, signed, stamped, and registered in a log containing its number and the name of the person or family who received it.

As

word spread among the Jewish community in Kaunas, the crowd in front of the

consulate mushroomed. To speed up the process Sugihara ordered his staff,

including his German assistant Wolfgang Gudze, to assist him.

“How can I handle a thousand visas?”

Among those who came to the consulate was Moses Zupnik, a yeshiva student who

looked barely out of his teens. His purpose? To obtain 300 visas for the Mir

Yeshiva, a Jewish school for religious education.

Zupnik later recalled: “I came in, and I was all excited. And I saw that he measured me. He was sitting at his desk and he was measuring me from the top to the bottom. Who I am? What I am? I said to him, ‘I am a representative of the Mir Yeshiva, and we want to go to Curacao. We just want to go through Japan.”’

Zupnik fidgeted nervously as he awaited Sugihara’s response. To his amazement, Sugihara agreed to write all 300 visas.

“I still remember when he looked at me, when he said, ‘Alright I’ll give you all the visas.’ I don’t forget these things, because they are still all alive in me. He saw people suffering, and he thought maybe he could help. And he helped.”

When Zupnik returned a few days later to pick up the visas, he found Wolfgang Gudze fraught with panic. “How can I handle a thousand visas?”

Zupnik said, “You know what? I will help you.”

When Sugihara heard about the offer, he said to Gudze, “Let him help you.”

For the next two weeks, Zupnik and Gudze worked side by side assisting Sugihara. During that time, Gudze made a deep impression on Zupnik. “He was a zaddik, a groyse zaddik” (a righteous man), Zupnik said years later.

But others reported that Gudze was a Gestapo agent

Then on 2 August, a cable from the Japanese Foreign Ministry arrived, ordering Sugihara to shut down the consulate immediately. Since the Soviets had forcibly “annexed” Lithuania into the U.S.S.R. in late July, they did not want any consulates in Kaunas. Sugihara fired off a passionate appeal to the Soviet Embassy for a delay. He was told that his request would be placed under consideration.

Sugihara speeded up the visa writing process again. Soon he was working 16 hours a day. By evening his hands ached so fiercely that Yukiko had to massage them before he could fall asleep.

On 10 August. Sugihara saw that the ever-swelling crowd now included the poorest of the poor, late-comers who lacked the connections to hear about the goings-on in the Japanese consulate. “They all seemed very tired and exhausted,” Sugihara wrote. “I did not know whether they had any place to sleep in Kaunas, maybe they just slept in the station or on the street.”

Sugihara told his staff that from now on he would issue visas even to those whose documents were obvious forgeries, even to those with no documents at all.

In mid-August, the long-dreaded reply for an extension from the Soviets arrived. Hands trembling, Sugihara slit the envelope open. Gudze heard him sigh with relief. Inexplicably, the Soviets had agreed to an extension until 28 August.

The unexpected news reinvigorated Chiune. Yukiko offered to help write visas, but he refused, firmly ordering her to stay as far away from the consular office as possible. Perhaps he didn’t trust Gudze. Most likely, he didn’t trust anybody. What he was sure of was that the responsibility for his actions should fall on his shoulders alone.

Former

Japanese consulate in Kaunas.

“Banzai Nippon!”

Then came a final warning from Japan. Close the consulate immediately and

leave. Chiune told Yukiko to start packing, while he, Gudze, and Zupnik

continued writing visas.

On 28 August, their suitcases packed and all documents burnt, the Sugihara family squeezed into the black Buick and drove off.

By this time Chiune Sugihara was worn out.

“He was so exhausted, like a sick person.” Yukiko recalled. “Even though he was ordered to go to Berlin, he said he couldn’t make it to Berlin and suggested we go to a hotel and rest before leaving.”

On the gate, Sugihara had left a note for the refugees. It said that he would be staying at the Metropolis Hotel.

Even before he could settle into his room, Sugihara got an urgent message from the hotel desk. He was needed downstairs. Having read the note on the gate, the refugees had followed him to the hotel. Sugihara wrote more visas. He wrote and he wrote until the family finally had to leave for the station and board the train for Berlin.

The refugees followed.

On the train, Sugihara continued to write visas on plain paper, signing them and flinging them indiscriminately to outstretched hands in the hope that the refugees would fill them in and find a way to outwit the Soviet and Japanese officials on their own.

As the train moved away from the station, Sugihara heard a voice shout, “Banzai Nippon!” Others joined the chorus. “Banzai Nippon! Banzai Nippon!’ These words meant “Long live Japan!” Sugihara had told some of the refugees to say this when they encountered Japanese officials.

Some witnesses reported they heard Sugihara say, “Please forgive me. I cannot write anymore. I wish you the best.”

Chiune

Sugihara memorial in Vilnius.

“I

may have disobeyed my government, but if I didn't I would be disobeying God."

Chaim Ganor never sold his business. He and dozens of other family

members, including Aunt Anushka, were sent to German concentration camps. Only

Chaim, Solly, and Solly’s sister survived.

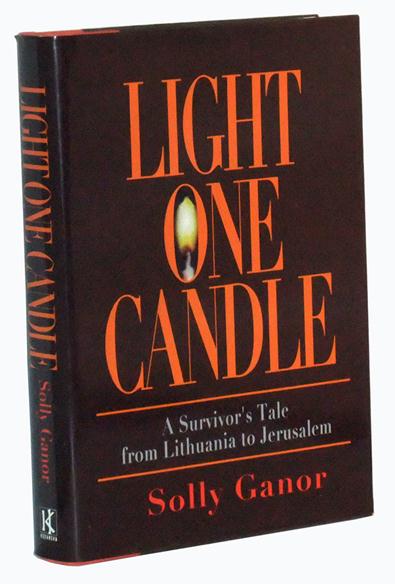

On May 2, 1945, Solly Ganor lay nearly

frozen under a blanket of snow. A four-man signal unit of the US 522th

artillery battalion was passing by, when one of the soldiers looked back and

said, “Hold it fellow, something strange is lying there in the snow.”

They found a whole group of people in striped clothing. The soldier picked

Solly up. Solly looked into his eyes and saw that they looked strangely

familiar – slanted. The soldier was Corporal Clarence Matsomura. Years later

Solly and Clarence met again in Jerusalem. In 2003, Solly Ganor’s book Light

One Candle: A Survivor’s Tale from Lithuania to Jerusalem was published.

Moses Zupnik, who came to ask Sugihara for 300 visas for the students of the Mir Yeshiva and stayed to help write visas during the two final weeks at the consulate, made it to Japan. The Japanese sent him and the other students to Shanghai, where they stayed until the war ended. Moses went to America and settled in New York City, where he became a rabbi.

Wolfgang Gudze is said to have reluctantly joined the German army. Once, when Moses Zupnik asked Gudze how he could thank him, Gudze replied. “You don’t have to thank me. But the world is a wheel. Today Hitler is on top. Tomorrow he may be down. Don’t forget what I did.” Zupnik never heard from Gudze again.

Although Mr. Rosenblatt and his little daughter Lea obtained their visas, I have not been able to learn if they survived the Holocaust.

Soon after arriving in Berlin, Chiune Sugihara was posted to Prague, where he and his family got a much-needed rest. Even so, he continued writing visas in Prague, and later in Koenigsburg, his last diplomatic post.

After the war, he and his family were detained by the Russians in one internment camp after another. The Soviet Union had declared war on Japan in August of 1945. When he returned to Japan, Chiune Sugihara was summarily dismissed from the Foreign Service in 1947. His youngest son Haruki died shortly after, but four years later a new son was born. To support his family, he worked at odd jobs, including selling light bulbs.

In 1960, because of his fluent command of the Russian language, Sugihara got a job for a trading company that did business with the Soviet Union that required him to live in Moscow. He visited his family from time to time for sixteen years until his retirement.

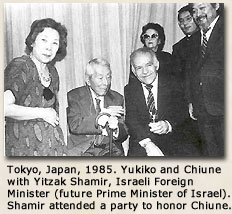

In 1968, Jehoshua Nishtri, an Israeli diplomat in Tokyo and one of the Jews Sugihara had helped save, finally tracked Sugihara down. Together with others, he lobbied the Israeli government for Chiune Sugihara’s inclusion in the Yad Vashem memorial, which was granted after extensive research, in 1985. By this time, Chiune was ill. Yukiko went to Israel and accepted the honor on his behalf. In gratitude for his deeds, Chiune Sugihara and his descendants were granted Israeli citizenship in perpetuity.

Nobody knows exactly how many visas Chiune Sugihara issued to Jewish refugees. He reported to the Japanese Foreign Ministry that he had issued 2,132 visas of which 1,500 were to Jews. It is estimated that he helped save anywhere from 6,000 to 10,000 Jews. At least 40,000 descendants of Sugihara visa-holders are alive today.

In Japan, Chiune Sugihara was honored in the year 2000 on the 100th anniversary of his birth. He had been born on January 1, 1900 – the first day of the 20th century. In 2002, a bronze statue of him was erected in the Little Tokyo district of Los Angeles in the United States.

The Polish Government posthumously awarded him the Commander’s Cross with the Star of the Order of Polonia in 2007.

In Kaunas, the Sugihara Museum now stands what used to be the Japanese Consulate at 30 Vaizgantas Street, which for a short time in the Year of Shame 1940 became the moral capital of the world.

References

Chiune Sugihara. In Wikipedia. Retrieved December 23, 2012, from http://en.wikipedia.org/Chiune_Sugihara.

Gold, Alison Leslie. A Special Fate: Chiune Sugihara, Hero of the Holocaust. New York: Scholastic Press, 2000.

A Japanese Holocaust Rescuer. Retrieved December 23, 2012, from http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=h0lizzqOxuI.

Levine, Hillel. In Search of Sugihara: The Elusive Japanese Diplomat who Risked his Life to Rescue 10,000 Jews From the Holocaust. New York: Free Press, 1996.

Paldiel, Mordecai. “Sempo Sugihara.” In The Path of the Righteous: Gentile Rescuers of Jews During the Holocaust, 252-257. Hoboken, N.J.: Ktav Publishing House, 1992.

Solly Ganor – Remembrance – Ron Greene.Com. Retrieved December 23, 2012, from www.rongreene.com/sollyintro.html.

Sugihara – The Conspiracy of Kindness. 4/6. Retrieved December 23, 2012, from http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ISsybs_89mQ.

Yad Vashem. “Visas to Japan: Chiune Sempo Sugihara.” Retrieved December 23, 2012 from http://www1.yadvashem.org/yv/en/righteous/stories/sugihara.asp.

Sugihara's widow with Lithuania's then president Valdas

Adamkus at

a tree planting ceremony in Vilnius, Lithuania in 2001.

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

Kaunas was an important centre of Jewish life

- Posted by - (4) Comment

Kaunas Synagogue is one of two operating choral synagogues in Lithuania.

Jews are first known to have lived in Kaunas (Kovno) as early as 1410 when they were brought forcibly as prisoners of war by the Grand Duke Vytautas. Many of those Jews were later active as traders between Kovno and Danzig (today's Gdansk, Poland). Living conditions for many Jews were squalid. In 1858, archaic living restrictions were relaxed and all but 6,000 of the city's 35,000 Jews flocked to the Old Town in search of something better. In July 1941, however, the Nazis expelled all the Jews from the town and sent them back to Slobodka. The Kovno Ghetto was thus established.

Kaunas became an important center of Jewish cultural life in the latter half of the 19th century. Distinguished Jewish leaders moved here from Vilnius, the capital, to establish yeshivas. Influential thinkers also moved to Kaunas.

When Vilnius was annexed by Poland during the interwar years, Kaunas became the provisional capital of Lithuania. In 1928, there were 1,000 Jewish students at the Vytautas Magnus University. There was even a Semitic studies program.

In 1931, the Jewish Ethnographic Museum was opened. Within only a few years, it had collected some 3,000 Jewish art works and artifacts. By the mid-1930s there were successful Jewish writers, poets, and artists residing in the city. By 1938, the Jewish population was nearly 40,000 and the area was a booming hub for Jewish businessmen, entrepreneurs, artisans, doctors, and lawyers. Five Jewish newspapers were published daily. There were schools for all ages, adult training centers, theatres, libraries, sports clubs, and political groups. Even the Central Jewish Bank of Lithuania was centered in Kaunas.

Kaunas Synagogue is one of two operating choral synagogues in Lithuania. It is located in Centras eldership, Kaunas. The Neo-Baroque synagogue was built in 1872. In 1902, before the Holocaust in Lithuania, the city had some 25 synagogues and prayer houses.

Dating from 1871, this radically designed synagogue, once one of over 35 synagogues and Jewish prayer houses in the city, claims to have one of the most beautiful altars in the entire Jewish world. A memorial to the estimated 50,000 Lithuanian Jewish children killed during the Holocaust can be found at the rear of the building, complete with 37 stone tablets showing in which towns and cities they lost their lives and just how many of them died in each one.

Kovno video:

Jewish bank in Kaunas

See also: https://vilnews.com/?p=12028

In pre-war Lithuania, many members of the Jewish middle class, especially the educated strata, who had already experienced to some extent the establishing of Jewish autonomy, mobilized their resources for the strengthening of the social economic basis of the Jewish masses and their livelihood. With the blessing and initiation of the Economics Committee at the Ministry for Jewish Affairs and with the assistance of the “Foundation”, a national financial system was established of co-operative credit societies. By the end of 1920, these were already active in 44 cities and towns and were named “Peoples Bank” (in Yiddish Folksbank). In addition to the positive local economic activity (extending loans etc) they were also of importance in the social and cultural sphere. In a number of places, the community organs and other organizations also used the bank building. There were also cases of the bank granting study scholarships and prizes for cultural activities.

In order to co-ordinate and regulate the activities of the Peoples Banks in time of need and crises and other difficulties, a central institution was established in 1921, formally called the “Central Jewish Bank for the Encouragement of Co-operation.” 71 Peoples Banks throughout the country linked to it, and the number of (dues paying) members reached 11,000. Over the years, the capital assets of the institutions increased, as did also the amount of deposits and savings. Thanks to that, the conditions were eased under which the loans were granted to members and public institutions. In 1930, 85 Peoples Banks existed in Lithuania with 22,262 members. In that year, 11,953 loans were granted to them and to others in a total amount of 10,249,159 Lit (approximately one million Dollars).

Although the Peoples Bank was open to non-Jews as well, this figure was no more than 5%. The work in the offices, the correspondence and the daily work routine was conducted in Yiddish, and this was also true of the national conventions and conferences, which took place every few years. This was therefore, a Jewish banking system spread throughout the cities and towns of Lithuania. At that time, the total deposits amounted to 14,113,413 Lit (approximately $1.4 million), of which 46% came from the members, 16% from institutions and 48% from non-members. If we take into consideration the members families and all others requiring the Peoples Banks' services, and that of its associates, then we can conclude that they served about two thirds of the Jewish population. Unlike the similar Lithuanian banks, which enjoyed cheap governmental credit, the Peoples Banks had to depend on deposits only. In 1933, a special bank was established to assist Jewish farmers (Yiddisher Landwirten Bank).

The central office was in Kaunas with 31 branches spread out in towns through the land.

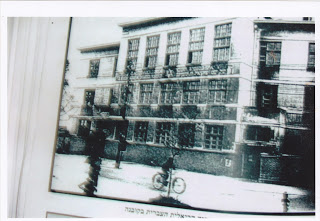

The Central Jewish Bank. Kaunas 1923.

Read more:

http://www.jewishencyclopedia.com/articles/9490-kovno

http://kehilalinks.jewishgen.org/kovno/kovno.html

http://www.northernjerusalem.com/objektai/locations/the-schwabe-hebrew-gymnasium-in-kaunas

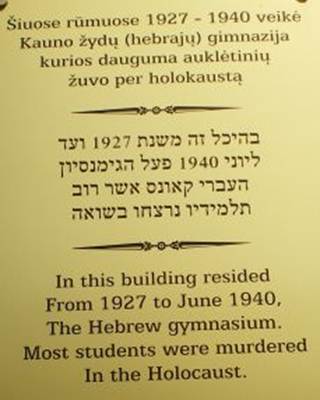

Hebrew Real ("Reali") Gymnasium in Kovno/Kaunas, Lithuania before WWII

From http://aaronrachovich.blogspot.com/2012/01/hebrew-real-gymnasium-in-kovnokaunas.html#.UNq2L-Ssh8E

My father Aaron Rachowitz attended the Hebrew Real/Reali Gymnasium (Kauno žydų realinė gimnazija, today Kęstučio g. 85 [1] formerly Kęstučio g. 59, in front of the theater/Valstybės teatras בית הריאל-גימנסיון העברי בקאונס) in Kovno/Kaunas for four years, i.e., completed four grades/classes: from 1936 to 1940 (the above pictures [2]show the gymnasium building then and today). His younger brother, Nathan Rachowitz, also attended this school. My father's good friend Eliyahu Stoupel (later to become a well known cardiologist in the world -- Professor Eliyahu Stoupel[3]), was his classmate. Most of their friends and classmates were killed during World War II in Kaunas, at Dachau and other locations. Hadassah Gorbulski (the sister of the famous Lithuanian composer Benjaminas Gorbulskis), Shura Katz, David Shein (former EL AL director in New York), Shlomo Yarmovski and Nissim Krakinovski were among those who survived the Holocaust. [4] The school's principal language of instruction was Hebrew but students communicated among themselves in Yiddish. They also studied Latin and Lithuanian. All courses -- except for Lithuanian language, literature and history -- were taught in Hebrew. According to my Dad, the gymnasium was a private institution. If parents do not pay their tuition fee on time (by the due date), the students will be reminded, in front of the whole class, to settle the debt. The gymnasium was on the name of Edward Azriel Chase (Eduardas Čais or Čaisas in Lithuanian), the famous Jewish philanthropist who was born (1874), grew up and spent the greater part of his youth in Tsarist Alytus/Alite (between the two World Wars and since the end of World War II, the town has been a part of Lithuania), but later immigrated to the United States and lived in Manchester, New Hampshire. With his financial help, a new building was erected for the Hebrew Real Gymnasium in 1930 (pictures above) in Kaunas (a formal inauguration dates from August 30, 1931, in the presence of the Lithuanian Minister of Education Konstantinas Šakenis, the mayor/burmistras of Kaunas, Juozas Vokietaitis, as well as Edward Chase and his wife, and many others---250 guests took part in the event), where thousands of Jewish children received their education and Jewish upbringing. The Hebrew Real/Reali Gymnasium had a good academic reputation all over the country (The roots of this gymnasium go back to 1915, i.e., the period of German occupation of Lithuania. Jüdische Realgymnasium was founded by Jewish-German Rabbi Dr. Joseph Hirsch Carlebach, who was charged by the German Occupation Authority in Lithuania with organizing a secondary school system. By the late 1920s, the gymnasium had earned good name but lacked adequate premises, i.e., had been housed in various locations/rented buildings). The total cost of the project, including Chase funding, was estimated in 1931 at 700,000 LT (approximately $70,000). The new gymnasium building (nauji žydų realinės gimnazijos rūmai)accommodated both girls' classes and boys' classes. It had two big halls: the gymnastics hall and the celebration hall; 19 classes; physics cabinet; a technical drawing hall; buffet; 4 wardrobes; 4 rooms with showers. Every floor had twocorridors and etc. [5] The Hebrew Real Gymnasium was designed by Baruch Kling who also supervised the construction. From an architectural point of view, the gymnasium has features derived from the German Bauhaus style or Dutch De Stijl style. [6] Edward Chase also established the Chase Fund that gave dozens of Jewish students the possibility of studying abroad or in Lithuanian universities. In addition, Chase established a scholarship fund to help outstanding students from different religious backgrounds. He contributed much for the development of his native town of Alytus (built houses, awarded scholarships to local students, etc). And his last dream during his visit to Lithuania in 1938 was to turn his former house in Alytus into a Jewish cultural center for Lithuanian youth. At its peak, the Hebrew Real Gymnasium had 40 teachers and 1,000 students. Dr. Zemach Feldstein had been the director of the gymnasium during 1922-1940. By the way, My Dad served as a goalkeeper on the school's football team, defended staunchly the goal and had been called (in Yiddish): "ארקה די הינדשה פלייש" ("Arke die hundische fleisch").

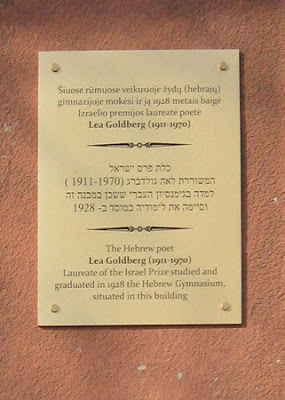

The Jews had enjoyed full cultural autonomy in prewar Kaunas, according to my Dad. In addition to the Hebrew Real/Reali Gymnasium, my Dad also mentioned frequently other Jewish gymnasia and schools that were established in the city: a "Yavne" Hebrew Gymnasium for girls; a "Yavne" Hebrew Gymnasium for boys. Yavne schools were well known for their strong religious education and were partially supported by religious-Zionist Mizrachi organization; a leftist "Commerce" Yiddish Gymnasium (named later after Shalom Aleichem); the Hebrew Gymnasium headed by Dr. Moshe Schwabe and thus called the "Schwabe" Gymnasium (In 1924, Dr. Schwabe immigrated to Eretz-Israel where he was a lecturer in the newly created Hebrew University of Jerusalem and later became its rector. A prolific Hebrew language poet, Leah Goldberg, studied at "Schwabe" Hebrew Gymnasium from 1920 to 1928---please see a commemorative plaque below. By the way, students of the "Schwabe" Gymnasium were sometimes called in Yiddish: "שוואבה די גרינע זשאבע" according to my Dad/"schwabe die grüne zhabe" which means: schwabe the green toad). The Schwabe Gymnasium (the picture of a new building inaugurated in 1927, below) had Revisionist Zionist orientatation; the Hebrew Tarbut Gymnasium affiliated with the Socialist Zionist party Mapai (my Dad's best friend, Dr. Semen Yakobson, at first studied at the Tarbut Gymnasium until 1940, but with the advent of Soviet rule moved to the Shalom Aleichem Gymnasium/previously known as "Commerce" Gymnasium, occupying since the Soviet era the former building of the Schwabe Gymnasium, located on the banks of the Nemunas River [7]---please see the building of the Schwabe Gymnasium, below); Hebrew "Tarbut" schools with strong secular nationalist Zionist orientation. There was also one Jewish gymnasium where students were taught in Lithuanian language. Hundreds of Jewish youth from all over country continued their education in the Lithuanian University of Kaunas (in 1930 the university was renamed to Vytautas Magnus University/Vytauto Didžiojo universitetas). Kaunas had many Jewish associations, organizations, student unions and sports unions, like Maccabi and Hapoel. The Jewish youth joined the Zionist movements like Hashomer Hatzair and Beitar---the Hebrew Real Gymnasium, where my Dad studied, was well known for its support for the Beitar movement, according to my Dad. The young Jews were trained for immigration to and life in Eretz Israel. "Kibbutz Hachshara" (Training Kibbutz) on behalf of "HeChalutz" Zionist youth movement acted in Kaunas. Many of these "Chalutzim" made "Aliyah" to Eretz Israel. The "Tarbut" association initiated public lectures in Hebrew. Throughout the interwar period a Yiddish theater operated in Kaunas. Also, the Jews of Kaunas were privileged to have had theater shows from Poland, the United States and Eretz Israel (the “Habima” theater, "Haohel" theater, etc. Ida Kaminska, for example, performed in Kaunas). A drama studio was run in Hebrew. In the interwar period, more than 100 books in Hebrew were published in Kaunas and etc. Professor Dov Levin wrote that Lithuania's Hebrew educational institutions in the interwar period "not only gave their pupils a solid education in Judaism and Hebrew culture, as well as in the sciences and the arts, but also encouraged them to be active in youth movements, sporting associations, student groups, and training groups preparing to emigrate to Palestine. In fact, Lithuania came to be known as the 'Second Eretz Israel,' in no small measure thanks to the varied and wide-ranging network of Hebrew schools, which was quite unparalled throughout the Jewish world." [8] On a visit to Kovno/Kaunas in the 1930s, the foremost Hebrew poet of modern time, Hayim Nahman Bialik said: "if Vilna is known as the Yerushalayim DeLita [Jerusalem of Lithuania], then Jewish Lithuania should be known as the Eretz-Israel deGaluta [The Land of Israel of the Exile].

____________________________

[1] The Hebrew Real/Reali Gymnasium building now serves as a music school (Kauno apskrities Juozo Naujalio muzikos gimnazija).Dr. Semen Yakobson drew my attention to the fact.

[2] The second photo, by courtesy of Prof. Eli Stoupel. The third photo was found on the web: KVB, Kaunas: Datos ir Faktai. Fotogr. R. Vaitilavičienė (2009 m.).

[3] Please see Prof Stoupel's new book: Space Weather and Timing of Cardiovascular Events, LAP Lambert Academic Publishing, 2012

[4] Information provided by Prof Eliyahu Stoupel.

[5] For further details, please see "Nauja Žydų Kultūrinė Įstaiga: Jos labdarys p. Čais," Rytas, Sept 7, 1931, p 2 viahttp://www.epaveldas.lt/vbspi/biRecord.do?biExemplarId=122209

[6] Northern Jerusalem website

[7] Information provided by Dr Semen Yakobson.

[8] Dov Levin, The Litvaks: A Short History of the Jews in Lithuania, Yad Vashem Publications, 2000

Description: In 1927-1940, this building housed Schwabe (Švabės) Hebrew Gymnasium