THE VOICE OF INTERNATIONAL LITHUANIA

|

VilNews has its own Google archive! Type a word in the above search box to find any article.

You can also follow us on Facebook. We have two different pages. Click to open and join.

|

Featured black

- Posted by - (0) Comment

The Polish-Lithuanian

War 1919-1920

Part 3 of 4 - STRUGGLES for the VILNIUS REGION

Map of the (Polish) Republic of Central Lithuania (in green).

By Vincas Karnila, Associate editor

vin.karnila@VilNews.com

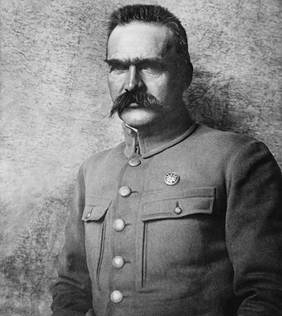

ZELIGOWSKI’S MUTINY

Polish chief of state Jozef Pilsudski ordered his subordinate, General Lucjan Zeligowski, to stage a mutiny with his 1st Lithuanian–Belarusian Division (16 battalions with 14,000 soldiers) in Lida and capture Vilnius in fait accompli.

The rebellion had two main goals, capture Vilnius and preserve Polish international reputation. The League of Nations was mediating other Polish disputes, notably over the Free City of Danzig and Upper Silesia, and direct aggression against Lithuania could have hampered Polish bargaining positions. While the Polish side officially stated Żeligowski to be a deserter and did not support him, Poland provided logistic support, including munitions and food rations, to his units. Żeligowski also received reinforcements when, according to the official version, the mutiny spread further among the Polish troops. His initial attack was secured on both sides by two Polish Armies.

The Żeligowski's Mutiny, in planning since mid-September, began in the early morning on October 8, 1920, just few hours after the signing of the Suwałki Agreement. A provisional agreement was made in the Polish–Soviet War, which freed up Polish units for the attack on Lithuania. As part of the rouse, Żeligowski wrote a note to Polish command announcing his mutiny and expressing his disappointment with the Suwałki Agreement. He claimed that his troops marched to defend the right of self-determination of the local Polish population.

READ TODAY’S ARTICLE – PART 3 OF 4

To read previous articles – GO TO OUR SECTION 10

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - (0) Comment

The Polish-Lithuanian

War 1919-1920

Part 2 of 4 - ADVANCES and RETREATS

The Battle of the Niemen River was the second-greatest battle of the Polish-Soviet War. It took place near the Neman River between the cities of Suwałki, Grodno and Białystok in today’s Poland and Belarus.

Su pagarbe Vincas Karnila, Associate editor

vin.karnila@VilNews.com

DIPLOMATIC DEVELOPMENTS

In April 1920 Poland launched the large-scale Kiev Offensive in hopes to capture Ukraine. Initially successful, the Polish Army started retreating after Russian counterattacks in early June 1920. Soon the Soviet forces began to threaten Poland's independence as they reached and crossed the Polish borders. On July 9, Polish Prime Minister Wladyslaw Grabski asked the Allied Powers in the Spa Conference (The Spa Conference was a meeting between the Supreme War Council and Weimar Republic in Spa, Belgium on 5–16 July 1920).

READ TODAY’S ARTICLE – PART 2 OF 4

To read previous articles – GO TO OUR SECTION 10

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - (2) Comment

The Polish-Lithuanian

War 1919-1920

Part 2 of 4 - ADVANCES and RETREATS

The Battle of the Niemen River was the second-greatest battle of the Polish-Soviet War. It took place near the Neman River between the cities of Suwałki, Grodno and Białystok in today’s Poland and Belarus.

Su pagarbe Vincas Karnila, Associate editor

vin.karnila@VilNews.com

DIPLOMATIC DEVELOPMENTS

In April 1920 Poland launched the large-scale Kiev Offensive in hopes to capture Ukraine. Initially successful, the Polish Army started retreating after Russian counterattacks in early June 1920. Soon the Soviet forces began to threaten Poland's independence as they reached and crossed the Polish borders. On July 9, Polish Prime Minister Wladyslaw Grabski asked the Allied Powers in the Spa Conference (The Spa Conference was a meeting between the Supreme War Council and Weimar Republic in Spa, Belgium on 5–16 July 1920).

It was the first post-war conference to include German representatives. The attendees included British and French Prime Ministers Lloyd George and Alexandre Millerand, German Chancellor Constatin Fehrenbach. The Conference mainly discussed disarmament of Germany and war reparations required by the Treaty of Versailles) for military assistance in the war with the Soviets. The conference proposed that the Polish forces would withdraw behind the Curzon Line, the Soviet forces would stop 50 km (31 mi) to the east of the line, the Lithuanian forces would take control of Vilnius, and all other disputes would be settled via negotiations in London. Grabski opposed the transfer of Vilnius, but under pressure of British Prime Minister Lloyd George, agreed to the resolution on July 10.

Advance of Soviet forces (red arrows) against Polish troops in June–August 1920

At the same time the Soviets and Lithuania negotiated the Soviet–Lithuanian Peace Treaty, which was signed on July 12, 1920. Russia recognized Lithuanian independence and withdrew any territorial claims. The treaty drew the eastern border of Lithuania, which the Lithuanians continued to claim as their de jure state border until World War II. The Vilnius Region, including Braslau, Hrodna, Lida and Vilnius, was recognized to Lithuania. On August 6, after long and heated negotiations, Lithuania and Soviet Russia signed a convention regarding withdrawal of Russian troops from the recognized Lithuanian territory. However, the troops began to retreat only after the Red Army suffered a heavy defeat in Poland.

TERRITORIAL CHANGES

The Bolshevik forces reached the Lithuanian territory on July 7, 1920, and continued to push back the Polish troops and subsequently the Lithuanian Army moved to secure territories abandoned by the retreating Polish forces. They took Turmantas on July 7, Tauragnai and Alanta on July 9, Širvintos and Musninkai on July 10, Kernavė, Molėtai and Giedraičiai on July 11, Maišiagala and Pabradė on July 13. On July 13 the Polish command decided to transfer Vilnius to the Lithuanians in accordance with the resolution of the Spa Conference. Lithuanians tried to move in but their trains were stopped by Polish soldiers near Kazimieriškės. This delay meant that the Bolsheviks were the first to enter Vilnius on July 14. By the time the first Lithuanian troops entered the city on July 15, it was already secured by the Soviets. Poland sought to have Russians in the city as it would create much less complications when Polish Army counterattacked. Despite the Peace Treaty, the Soviets did not intend to transfer the city to the Lithuanians. Indeed there were indications that the Soviets planned a coup against the Lithuanian government in hopes to establish the Lithuanian SSR (Lithuanian Soviet Socialist Republic)

Despite the setback in Vilnius, the Lithuanians continued to secure territories in the Suwałki Region. Lithuanian forces took Druskininkai on July 17, Vištytis, Punsk, Giby, and Sejny on July 19, Suwałki on July 29 and Augustów on August 8. The Polish units, afraid of being surrounded and cut off from the main Polish forces, retreated towards Lomza. The Lithuanian authorities started to organize themselves in the regained areas.

LITHUANIAN NEUTRALITY

Poland claimed that Lithuania violated its claim to neutrality in the Polish–Soviet War and in effect became a Soviet ally. A secret clause of the Soviet–Lithuanian Peace Treaty allowed Soviet forces unrestricted movement within the Soviet-recognized Lithuanian territory for the duration of Soviet hostilities with Poland. This clause was more of a practical matter since Soviet troops already occupied much of the assigned territory and could not and would not withdraw while hostilities with Poland continued. Lithuanians were also simply unable to resist the Soviets and their troops. For example, when Lithuanians refused a permission to use a road, the Soviets ignored Lithuanian protests and transported their troops and equipment regardless. At the same time Polish soldiers were disarmed and interned bt Lithuania. The largest group, a brigade under colonel Pasławski, was interned on July 18, 1920, near Kruonis. On August 10, Lithuanians held 103 Polish officers and 3,520 private soldiers. Poland also claimed that the Lithuanian troops actively participated in military operations of the Red Army. This charge, based on memoirs of Soviet officials, lacks evidence. Further military clashes between Polish and Lithuanian troops in the Suwałki Region were interpreted by Poland to show that "the Lithuanian government has become an instrument of the Soviet government." Lithuania responded that it was defending its borders.

AUGUST to OCTOBER 1920 – STRUGGLES FOR THE SUWALKI REGION

POLISH ADAVANCE AND SOVIETS RETREAT

The Russians suffered a great defeat AT the Battle of Warsaw in mid-August 1920 and started withdrawing. They handed over Vilnius to the Lithuanians on August 26. The Lithuanians hastily made preparations to secure the border, as determined by the Soviet–Lithuanian Peace Treaty. The soldiers were ordered to maintain neutrality: avoid hostilities and intern any Soviet or Polish troops that would cross the border. On August 26, a Polish delegation, led by colonel Mieczyslaw Mackiewicz, arrived in Kaunas to negotiate the situation. The Poles, lacking authority to discuss political issues, were concerned with military aspects.

They sought permission to transport Polish troops through the territory of Lithuania, wanted access to a portion of the Warsaw–Saint Petersburg Railway and demanded that the Lithuanian troops would withdraw from the Suwałki Region behind the Curzon Line. The Lithuanians refused to discuss military matters without a clear political Polish–Lithuanian border that would be respected after the war. Due to these fundamental disagreements and Polish attacks, the negotiations broke down on August 30.

Map of the Suwałki Region. Its many forests and lakes complicated the military actions.

The Suwałki Region had strategic importance in the Polish–Soviet War. Following orders of Edward Rydz-Śmigły, Polish forces took Augustów from Lithuanians in a surprise attack on August 28. Confused and disoriented Lithuanians retreated from Suwałki and Sejny on August 30 and 31. The Lithuanians reorganized, gathered their forces (11 battalions with 7,000 soldiers) and organized a counterattack to "defend their border" on September 2. The goal was to take and secure the Augustów–Lipsk-Hrodna line. The Lithuanians succeeded in taking Sejny and Lipsk and by September 4 reached the outskirts of Augustów. On September 5, the Poles counterattacked and forced the Lithuanians to retreat. On September 9, the Polish forces recaptured Sejny but the Lithuanians pushed back and regained Sejny and Giby on September 13 and 14. Pending direct negotiations, hostilities were ceased on both sides.

DIRECT NEGOTIATIONS and the LEAGUE OF NATIONS

On September 6, Lithuanian Foreign Minister Juozas Purickis proposed direct negotiations in Marijampolė. On September 8, during a planning meeting of the Battle of the Niemen River, the Poles decided to maneuver through the Lithuanian territory to the rear of the Soviet Army, stationed in Hrodna In an attempt to conceal the planned attack, Polish diplomats accepted the proposal to negotiate. The negotiations started on September 16 in Kalvarija but collapsed just two days later.

Juozas Purickis

On September 5, 1920, Polish Foreign Minister Eustachy Sapieha delivered a diplomatic note to the League of Nations alleging that Lithuania violated its neutrality and asking to intervene in the Polish–Lithuanian War.

The League agreed to mediate and began its session on September 16. The resolution, adopted on September 20, urged both states to cease hostilities and adhere to the Curzon Line. Poland was asked to respect Lithuanian neutrality if Soviet Russia agreed to do the same. Also a special Control Commission was to be dispatched into the conflict zone to oversee implementation of the resolution. It was clear that the League had only a narrow goal to prevent armed hostilities and not to resolve the underlying territorial dispute. The Lithuanian government accepted the resolution, while Poland reserved full freedom of action in preparation for the attack on the Soviets.

BATTLE of the NIEMAN RIVER

On September 22, 1920, Poland attacked Lithuanian units in the Suwałki Region on a wide front. Overwhelmed by 4–5 times larger enemy forces, some 1,700–2,000 Lithuanian troops surrendered and were taken prisoners. Polish forces then marched, as planned on September 8, across the Neman River near Druskininkai and Merkinė to the rear of the Soviet forces near Hrodna and Lida. The Red Army hastily retreated. The Lithuanians had limited intelligence warnings about such attack and as a result chose an inadequate defensive strategy and spread their forces too thinly along the entire Polish–Lithuanian front without sufficient forces to protect bridges across the Neman.

Map of the Battle of the Niemen river. Polish forces maneuvered through the Lithuanian territory (front line in red) to the rear of Soviet troops despite the resolution by the League of Nations to cease hostilities

This attack, just two days after the resolution by the League of Nations to cease hostilities, put more pressure on Poland to settle the dispute peacefully. On September 26, Poles captured Hrodna and Polish Foreign Minister Sapieha proposed new negotiations in Suwałki. The Battle of the Niemen River drastically altered the balance of power. Vilnius, in Lithuanian hands since August 26, was exposed to a Polish attack. Indeed Poles had already decided to capture the city and used the negotiations in Suwałki to stall and buy time for necessary preparations. The Lithuanian side was ready to give up the Suwałki Region in exchange for Poland's recognition of the Lithuanian claims to Vilnius.

SUWALKI AGREEMENT

The negotiations between Poles, led by colonel Mieczyslaw Mackiewicz and Lithuanians led by general Maksimas Katche, began in the evening of September 29, 1920. Both sides agreed to an armistice, but only to the east of the Neman River (the Suwałki Region).

Fighting to the west on the river continued around Marcinkonys, Zervynos, Perloja and Eišiškės. A major point of contention, both diplomatic and military, was the train station in rėna (Orany) on the Warsaw – Saint Petersburg Railway. Major Lithuanian forces were still concentrated in the Suwałki Region and moving them to protect Vilnius without the railway would be extremely difficult. Fighting west of the Neman River ceased only on October 6, when Polish troops had already captured the train station in Varėna.

Selected demarcation lines between Poland and Lithuania. Line drawn by the Suwałki Agreement is in yellow; the final interwar border is in orange. The current borders of Lithuania, Poland and Balta Rusija that were established after the Second World War are indicated by the purple lines

Negotiations regarding the demarcation line were difficult. In essence, the Lithuanians wanted a longer demarcation line to provide better protection for Vilnius. The Poles agreed only to a short line in order to provide the planned attack on Vilnius with space for operation. The Polish delegation was also stalling to buy time for necessary preparations for an attack on Vilnius. While Vilnius was not a topic of debate, it was on everybody's mind. On October 4, the Control Commission, sent by the League according to its resolution of September 20, arrived to Suwałki. The Commission, led by French colonel Pierre Chardigny, re-energized the negotiations. On October 7, at midnight, the final agreement was signed. The treaty made not a single reference to Vilnius or the Vilnius Region. The ceasefire was effective only along the demarcation line, which ran through the Suwałki Region to the train station in Bastuny. Thus the line was incomplete, did not provide protection to the Vilnius Region, but indicated it would be left on the Lithuanian side.

In Part 3

OCTOBER to NOVEMBER 1920 – STRUGGLES for the VILNIUS REGION

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - (0) Comment

The Polish-Lithuanian

War 1919-1920

South-eastern Lithuania, Vilnius included, was occupied by Poland

during the interwar period. Picture: Celebration of the incorporation

of Vilnius Region to Poland, 1922.

The Polish–Lithuanian War was an armed conflict between Lithuania and Poland in the aftermath of World War I and Lithuania's declaration of independence 16 February 1918.

VilNews' Associate Editor Vincas Karnila today introduces our readers to a series with a total of four articles about this war and the consequences it had for the relationship between the once good neighbours Poland and Lithuania.

The conflict primarily concerned territorial control of the Vilnius Region, including Vilnius, and the Suwałki Region, including the towns of Suwałki, Augustów, and Sejny. According to Lithuanian historians, the war was part of the Lithuanian Wars of Independence and spanned from spring 1919 to November 1920. According to Poland, the war included only fighting over the Suwałki Region in September–October 1920 and was part of the Polish–Soviet War.

After Vilnius was occupied by the Russian Bolsheviks in 1919, the government of the Republic of Lithuania established its main base in Kaunas. When Vilnius was forcibly annexed by Poland, Kaunas became the temporary capital of Lithuania, a position it held until 28 October 1939, when the Red Army handed Vilnius back to Lithuania. The Constituent Assembly of Lithuania first met in Kaunas on 15 May 1920. There were no diplomatic relations between Poland and Lithuania until 1938.

Introduction

As usually happens, the end of one hostility often results in the beginning of other hostilities. This was the case between Lithuania and Poland after the end of the First World War. With both countries in a state of war with Bolshevik Russia, defending themselves against Russia’s attempt to recapture and occupy the two countries that had just recently regained their independence, this helped to set the stage for armed conflict between the two neighbors. This combined with one country’s plan to control part of Europe, claims to land based on its population and the continued “carving up” of smaller countries by larger countries all helped to create what was known as the Polish – Lithuanian War which resulted in Lithuania losing its capital of Vilnius and other parts of its country to Polish occupation during the interim war period.

Dear readers we would like to invite you review this series which will offer insight as to what led to the conflict, the reasons and justifications, the participants, the areas of action and some of the key events. As always we warmly welcome any additional information and any comments you would like to share.

Su pagarbe Vincas Karnila, Associate editor

vin.karnila@VilNews.com

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - (4) Comment

|

War 1919-1920

The Polish–Lithuanian War was an armed conflict between Lithuania and Poland in the aftermath of World War I and Lithuania's declaration of independence 16 February 1918. VilNews' Associate Editor Vincas Karnila today introduces our readers to a series with a total of four articles about this war and the consequences it had for the relationship between the once good neighbours Poland and Lithuania. The conflict primarily concerned territorial control of the Vilnius Region, including Vilnius, and the Suwałki Region, including the towns of Suwałki, Augustów, and Sejny. According to Lithuanian historians, the war was part of the Lithuanian Wars of Independence and spanned from spring 1919 to November 1920. According to Poland, the war included only fighting over the Suwałki Region in September–October 1920 and was part of the Polish–Soviet War. After Vilnius was occupied by the Russian Bolsheviks in 1919, the government of the Republic of Lithuania established its main base in Kaunas. When Vilnius was forcibly annexed by Poland, Kaunas became the temporary capital of Lithuania, a position it held until 28 October 1939, when the Red Army handed Vilnius back to Lithuania. The Constituent Assembly of Lithuania first met in Kaunas on 15 May 1920. There were no diplomatic relations between Poland and Lithuania until 1938.

|

Introduction

As

usually happens, the end of one hostility often results in the beginning of

other hostilities. This was the case between Lithuania and Poland after the end

of the First World War. With both countries in a state of war with Bolshevik

Russia, defending themselves against Russia’s attempt to recapture and occupy

the two countries that had just recently regained their independence, this

helped to set the stage for armed conflict between the two neighbors. This

combined with one country’s plan to control part of Europe, claims to land

based on its population and the continued “carving up” of smaller countries by

larger countries all helped to create what was known as the Polish – Lithuanian

War which resulted in Lithuania losing its capital of Vilnius and other parts

of its country to Polish occupation during the interim war period.

Dear readers we would like to invite you review this series which will offer insight as to what led to the conflict, the reasons and justifications, the participants, the areas of action and some of the key events. As always we warmly welcome any additional information and any comments you would like to share.

Su pagarbe Vincas Karnila, Associate editor

vin.karnila@VilNews.com

Part 1 of 4 - THE BUILD UP

MILITARY DEVELOPMENTS

World War I ended on November 11, 1918 when Germany signed the Compiègne Armistice. On November 13, Soviet Russia renounced the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk (After signing the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk March 3 1918, Bolshevik Russia lost the European lands it annexed in the 18th century and 19th century. Most of today's Poland, Belarus, Ukraine and the Baltic States were passed to the government of Germany, which in turn decided to grant these states limited independence as buffer states) and began the Soviet westward offensive of 1918–1919. The Bolsheviks followed retreating German troops and attacked Lithuania and Poland from the east trying to prevent their independence. They attempted to spread the global proletarian revolution, establish Soviet republics in the region, and join the German and the Hungarian Revolutions. The Soviet offensive sparked a series of local wars, including the Polish–Soviet War and the Lithuanian–Soviet War. At first the Soviets were successful, but came to a halt in February 1919. In March–April both Lithuanians and Poles began their offensives against the Soviets. The three armies met in the Vilnius Region. The Polish–Lithuanian relations were not immediately hostile, but grew worse as each side refused to compromise. On April 19, 1919, the Polish Army captured Vilnius.

The

advance of Polish (blue arrows), Lithuanian/German (dark purple arrows) against

the Soviet forces in early 1919. The blue line shows the Polish front in May

1920. The red line shows the Soviet front in February 1919

At first, both Poles and Lithuanians cooperated in their offensive against the Soviets, but soon the cooperation gave way to increasing hostility. Lithuania claimed neutrality in the Polish–Soviet War. As the Polish Army forced its way further into Lithuania, the first clashes between Polish and Lithuanian soldiers occurred on April 26 and May 8, 1919, near the village of Vievis. Though there was no formal state of war and few casualties, by July newspapers reported increasing clashes between Poles and Lithuanians, primarily around the towns of Merkinė and Širvintos. Direct negotiations in Kaunas between May 28 and June 11, 1919, collapsed as neither side agreed to compromise. Lithuania tried to avoid direct military conflict and submitted its case for mediation to the Conference of Ambassadors (The Conference was formed to enforce peace treaties and to mediate various territorial disputes among European states. The Conference consisted of ambassadors of Great Britain, Italy, and Japan accredited in Paris and the French minister of foreign affairs. The ambassador of the United States attended as an observer because the U.S. was not an official party to the Treaty of Versailles).

DIPLOMATIC DEVELOPMENTS

Poland did not recognize the independence of Lithuania as Polish leader Józef Piłsudski hoped to revive the old Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth and campaigned for some kind of Polish–Lithuanian union in the Paris Peace Conference. Poland also did not intend to make any territorial concessions, justifying its actions not only as part of a military campaign against the Soviets but also as the right of self-determination of local Poles. According to the 1897 Russian census, the disputed city of Vilnius had an ethnic breakdown of 30% Poles, 40% Jews, and 2% Lithuanians; however the percentage of Lithuanians was much higher in the surrounding countryside. According to the 1916 German census, Poles constituted 50% of city's population. The Lithuanians claimed Vilnius as their historical capital and refused any federation with Poland, desiring an independent Lithuanian state.

They regarded Polish federalism as recreation of Polish cultural and political dominance. The Lithuanian government in Kaunas, designated as the temporary capital, saw the Polish presence in Vilnius as an occupation. In addition to the Vilnius Region, the Suwałki Region was also disputed due to the fact it had a mixed Polish and Lithuanian population. In effect what Poland was saying was that if many Poles lived in an area, the area should be/is a part of Poland regardless of the fact that the area was in another country.

At the time the international situations of newly independent Poland and Lithuania were unequal. Poland, much larger in territory and population, was dedicated point 13 in Woodrow Wilson's Fourteen Points (The Fourteen Points was a speech given by United States President Woodrow Wilson to a joint session of Congress on January 8, 1918. The address was intended to assure the country that the Great War was being fought for a moral cause and for postwar peace in Europe. Point 13 was – “An independent Polish state should be erected which should include the territories inhabited by indisputably Polish populations, which should be assured a free and secure access to the sea, and whose political and economic independence and territorial integrity should be guaranteed by international covenant”).

Poland was recognized by all nations of the Entente, officially invited to the Paris Peace Conference and became one of the founding members of the League of Nations. Poland also enjoyed a close alliance with France. Lithuania did not receive international recognition (it was first recognized formally in July 1920 by Soviet Russia) as the Entente hoped to revive the Russian Empire within its former territory, which included Lithuania. Lithuania was not invited to any post-war diplomatic conferences. It also had to battle negative propaganda that the Council of Lithuania was a German puppet, that Lithuanians harbored pro-Bolshevik attitudes or that Lithuania was too small and weak to survive without a union with Poland.

MAY to SEPTEMBER 1919 – RISING TENSIONS

DEMARCATION LINES

Map of

demarcation lines of June 18 (light green) and July 26 (dark green) between

Poland and Lithuania. Poland ignored both lines and continued to advance up to

the orange line. Railroads are marked by black stitched lines.

The Conference of Ambassadors drew the first demarcation line on June 18. The line, drawn about 5 km (3.1 mi) west of the Warsaw – Saint Petersburg Railway, was based on the military situation on the ground at that time rather than ethnic composition. Neither Poles nor Lithuanians were content with the line. The Polish Ministry of Foreign Affairs rejected the line as it would require the Polish forces to retreat up to 35 km (22 mi). The Lithuanians protested leaving Vilnius and Hronda under Polish control. As German volunteers were departing from Lithuania and Lithuanian forces were preoccupied with battles against the Soviets in northern Lithuania, Poland mounted an offensive on a 100 km (62 mi) wide front moving 20–30 km (12–19 mi) deeper into the Lithuanian territory and Lithuania could not organize an effective defense to counteract this offensive.

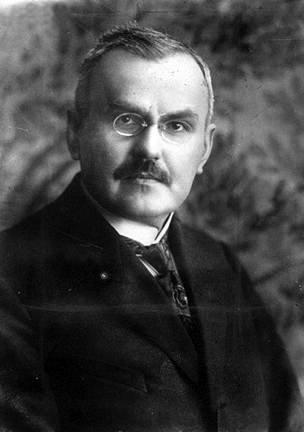

Ferdinand Foch

On July 18, Ferdinand Foch proposed the second demarcation line, known as the Foch Line. It was approved by the Entente on July 26. The Lithuanians were informed about the new line only on August 3. Two major modifications favorable to the Poles were made: the Suwałki Region was assigned to Poland and the entire line was moved about 7 km (4.3 mi) west. Again, both Poles and Lithuanians protested the line as it would require them to withdraw their armies from the Vilnius and Suwałki Regions respectively. The German administration, which had not yet retreated from the Suwałki Region, also opposed the Foch Line. The new line did not immediately halt the hostilities. After a couple of Polish attacks on July 29 and August 2, the front stabilized.

THE SEJNY UPRISING

The Lithuanians obeyed the Foch Line and retreated from Suwałki on August 7, 1919. However, they stopped in ethnically mixed Sejny and formed a line on the Czarna Hancza river – Wigry Lake. They showed their intention to stay there permanently, which caused concern among the local Poles. On August 12, the Poles of that area organized a rally of about 100 people demanding incorporation into Poland. The Sejny branch of Polish Military Organization (PMO) began preparing for an uprising, scheduled for the night of August 22 to 23, 1919 and between 900 and 1,200 partisans joined PMO forces. On August 23, the Poles captured Sejny and attacked the towns of Lazdijai and Kapčiamiestis on the Lithuanian side of the Foch Line. The insurgents planned to march as far as Simnas (located 23 km west of Alytus). Lithuanians recaptured Sejny on August 25 for a few hours. On August 26, Polish regular forces – the 41st Infantry Regiment – joined the PMO volunteers. On September 5, the Lithuanians agreed to withdraw behind the Foch Line by September 7. Poland secured Sejny and repressed Lithuanian cultural life: the Sejny Priest Seminary was expelled, Lithuanian schools and cultural organizations closed. After the uprising, the mistrust of Poles prompted Lithuanian intelligence to intensify its investigations of Polish activities in Lithuania. This helped to detect and prevent a planned coup d'état in Kaunas to overthrow the government of Lithuania.

Polish cavalry parade

in Sejny

THE PLOISH COUP ATTEMPT

Sometime in mid-July 1919, PMO forces in Vilnius began planning a coup to replace the Lithuanian government with a pro-Polish cabinet, which would agree to a union with Poland of the proposed Miedzymorzr federation, also known as Intermarium was a plan, pursued by Polish leader Jozef Pilsudski, for a federation, under Poland's control of Central and Eastern European countries, invited to join the proposed federation were the Baltic states of Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia, Finland, Belarus, Ukraine, Hungary, Romania, Yugoslavia and Czechoslovalia. The proposed federation was meant to emulate the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, stretching from the Baltic Sea to the Black Sea that, from the end of the 16th century to the end of the 18th, had united the Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. Intermarium complemented Piłsudski's other geopolitical vision of Prometheism, whose goal was the dismemberment of the Russian Empire and that Empire's divestment of its territorial conquests into Polish control. Intermarium was, however, perceived by some Lithuanians as a threat to their newly established independence, and by some Ukrainians as a threat to their aspirations for independence and was opposed by most Western powers.

Leon Wasilewski

Polish leader Jozeph Pilsudski believed there were enough Polish sympathizers in Lithuania to carry out the coup. On August 3, a Polish diplomatic mission led by Leon Wasilewski, in Kaunas had a double purpose: propose a plebiscite (common people’s law) in the contested territories and assess preparedness for the coup. On August 6, the Lithuanian government rejected the plebiscite proposal, stating that the disputed territories constitute ethnographic Lithuania. PMO planned to capture and hold Kaunas for a few hours until arrival of the regular Polish troops, situated only some 40–50 km (25–31 mi) east from the city. The coup would be portrayed as an initiative of the local population to "free Lithuania from German influence" while denouncing any involvement of the Polish government. Polish newspapers ran a propaganda campaign claiming that the Council of Lithuania was simply a German puppet. The coup was initially scheduled for the night of August 27 to 28, but was postponed to September 1. Lithuanian intelligence discovered the coup, but did not have a list of PMO members. Lithuanian authorities began mass arrests of some 200 Polish activists, including some officers of the Lithuanian Army. Kaunas was declared under a state of siege. Polish press saw the mass arrests of Polish activists "to whom no charge can be ascribed other than being Poles" as proof of systematic anti-Polish policies of the German-ridden Lithuanian government”. PMO was little affected by the arrests and scheduled another coup attempt for the end of September. However, Lithuanians obtained a full PMO membership list and liquidated the organization in Lithuania.

SEPTEMBER 1919 to JUNE 1920 - MORE POLISH ATTACKS

After the failure of the coup in Kaunas there were numerous incidents. On September 19, 1919, Polish troops attacked Gelvonai and continued towards Ukmergė. On several occasions fights broke out regarding a strategically important bridge over the Šventoji River near Verpriai. In October, when the main Lithuanian forces were deployed against the Bermontians (The West Russian Volunteer Army or Bermontians was an army in the Baltic provinces of the former Russian Empire during the Russian Civil War of 1918-1920) in northwestern Lithuania, the attacks intensified and Poles captured Salakas on October 5 and attacked Kapčiamiestis on October 12. The front stabilized, but harassment of border guards and local villagers continued throughout late 1919 and early 1920. In March 1920, the Poles attacked along the railroad stations in Kalkūni and Turmantas. The situation was investigated by British and French observers and reported to the Entente. The situation somewhat improved only in late spring of 1920 when most Polish troops were deployed to Ukraine during the Polish–Soviet War.

At the time Lithuania faced a severe budget crisis – in 1919 its revenue was 72 million while expenses reached 190 million German marks. While the government was struggling to obtain financial assistance and loans, deep cuts affected the army. Instead of increasing its armed forces to 40,000 men, Lithuania was forced to cut them to about 25,000.

In part 2 of 4 - ADAVANCES and RETEATS

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - (0) Comment

The pride of

being Lithuanian

Illustration from: http://www.cafepress.com

Text: Aage Myhre

aage.myhre@VilNews.com

I've been asked why VilNews puts relatively much emphasis on articles with historical content. I've also been asked whether our journey around Europe in January should be presented in a publication that otherwise focuses on Lithuania.

My response is as follows:

Sooner or later the history knocks

at the door of the present

Lithuania’s Foreign Minister Audronius Ažubalis recently said this about the still latent conflict between Armenia and Turkey on the mass killing that took place during the First World War. He is of course right, and the statement is valid for us all, also Lithuania.

The Lithuanian people have for 200 years largely been deprived of the opportunity to know their own nation's history presented in an objective and outspoken way. Those who published historical documentation here were often people who deliberately swept some parts of Lithuania's history under the carpet, exaggerated on other aspects and deliberately misinformed the people. During the years when Lithuania was under Tsarist Russia, Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union, truth and authentic information was often forbidden or falsified. Today it is no longer so, but I still feel that the knowledge about own history among the people here is not very deep or comprehensive in many cases.

Lithuania is a country that more than many others should be seen and understood in the light of historical perspectives...

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - (1) Comment

The pride of being Lithuanian

Illustration

from: http://www.cafepress.com

Text: Aage Myhre

aage.myhre@VilNews.com

I've been asked why VilNews puts relatively much emphasis on articles with historical content. I've also been asked whether our journey around Europe in January should be presented in a publication that otherwise focuses on Lithuania.

My response is as follows:

Sooner or later the history knocks at the

door of the present

Lithuania’s Foreign Minister Audronius Ažubalis recently said this about the still latent conflict between Armenia and Turkey on the mass killing that

took place during

the First World War. He is of course right, and the statement is valid for us

all, also Lithuania.

The Lithuanian people have for 200 years largely been deprived of the opportunity to know their own nation's history presented in an objective and outspoken way. Those who published historical documentation here were often people who deliberately swept some parts of Lithuania's history under the carpet, exaggerated on other aspects and deliberately misinformed the people. During the years when Lithuania was under Tsarist Russia, Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union, truth and authentic information was often forbidden or falsified. Today it is no longer so, but I still feel that the knowledge about own history among the people here is not very deep or comprehensive in many cases.

Lithuania is a country that more than many others should be seen and understood in the light of historical perspectives. It is only when one becomes familiar with this nation's dramatic background that one can begin to understand more about the nation’s values and qualities. And it is this perspective we want to have as a backdrop for our articles in VilNews.

We want our readers to have access to deep knowledge of what has happened of good and bad here. Also in cases when this enforces tough confrontations with the past. For example what happened during the Holocaust, the guerrilla warfare that took place in the post-war years, as well as the many abuses carried out by Soviet and its henchmen during WWII and the 50 years that followed.

But Lithuania has also an infinite amount of history to be proud of. Take as an example the 300 years when the country was a world superpower, known as the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. It was the wise leaders of this period who caused the British historian Norman Davies to describe Lithuania as "a haven of tolerance".

Lithuania’s dramatic, bloody history during the period 1919 – 1991

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Lithuania is back in the European family

Lithuania is back in good old Europe. A Europe that has seen dramatic changes through century after century, but that will forever remain "home & castle" for us Europeans. Lithuania played once a very significant role for this continent, but is now to be considered a newcomer into its former neighbourhood. It is, however, in this neighbourhood Lithuania belongs. And now it's time to get to know the neighbours and find the nation’s rightful place in this context.

You who have followed us on our journey through Europe in January, may have learned a little more about the different countries we visited. You may have also seen that there are prominent Lithuanian footprints in pretty much every European country.

Lithuania is now free to revive friendships and relations with its neighbours. Border crossings are open as never before. Despite the differences, it is here in the European family that Lithuania belongs.

But family and neighbourhood also represents commitments. This must be taken seriously.

Lithuanians have many good reasons to feel pride in their homeland. Having knowledge of historical and geographical context is an important prerequisite for the emergence of modern Lithuania, and our VilNews will therefore also in the future focus on bringing information that sheds light on these aspects.

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - (0) Comment

11 – 13 January 1991

days the world should never forget

The 1991 January events took place in Lithuania between January 11 and 13, in the aftermath of the Act of the re-establishment of the State of Lithuania. As a result of Soviet military actions, 14 civilians were killed and more than 1000 injured. The events were centered in Vilnius, along with related actions in the cities of Alytus, Šiauliai, Varėna, and Kaunas.

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - (0) Comment

![]()

EUROPE – MY HOME & MY CASTLE (2 of 10)

Switzerland & Italy

Today we start our little tour of Europe. Over the next few weeks, I invite you on a journey from north to south, from east to west. Some sections will dwell with history. Some with Lithuanian contact points in various countries. I have travelled across here with camera and notepad for nearly 40 years, and hope you will enjoy seeing and reading about some of my experiences. We start today's tour in Switzerland, and then continue to the south of Italy. Enjoy your trip!

Text and photos: Aage Myhre

aage.myhre@VilNews.com

To join the trip, go to our Section 11

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - (0) Comment

EUROPE

my home & my castle

Text and photos: Aage Myhre

aage.myhre@VilNews.com

The more I travel around the world the more I realize that I am European. Although I have had good, close friends and have experienced extraordinary things in all corners of the world. Maybe my mind is not sufficiently exotic. That's ok. I have grown older now. Europe does not lose lustre. Driving a car is the best way to experience Europe. Lithuania's border crossings to Latvia and Poland is no problem anymore. Within a day's drive you can reach most of the northern and central European countries. One more day and you can already stand and look out over the warm, slow waves of the Mediterranean Sea...

Over the next few weeks VilNews will present some glimpses of Europe ... A Europe that is now so close to everyone... The Iron Curtain is gone, forever!

|

1 |

|

Exploring Europe |

|

2 |

|

Switzerland & Italy |

|

3 |

|

Along the Riviera |

|

4 |

|

From Strasbourg to London |

|

5 |

|

Austria & Germany |

|

6 |

|

Finland & Scandinavia |

|

7 |

|

En route Warsaw - Budapest |

|

8 |

|

Moscow and further east |

|

9 |

|

The Baltic Hanseatic route |

|

10 |

|

Istanbul |

1 of 10: Exploring Europe

I love old towns. No matter how good a new suburb is. I, and many with me, prefer the old towns. It has something to do with the atmosphere. Details, ornaments. Human life. Sound and smell. Warmth. Joy.

Europe is the 'old town' for the entire world!

I think it primarily is about culture and history. All that Europe is so infinitely rich on. It is something about that feeling. The idea and the knowledge of the Roman Empire every time I'm in Rome. Recognition every time I visit a museum or gallery and see the many art treasures I feel is a part of my European self.

It is more to Europe I never get tired of. For example, being able to walk, touch, feel, smell. Being a tourist here is like walking on the world stage as it has provided the basis for so much over thousands of years. Fortunately, European leaders long ago realized that the human being is more important than cars. Take Strøget in Copenhagen, bike paths in Holland and promenades along pretty much all The Mediterranean sea-coast as good examples of this.

Europe means walking around on cobbled streets. Between historic buildings.

To see. Listen. Experience. Feel. Smell.

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

Nida tranquility

- Posted by - (0) Comment

Text and photos: Aage Myhre

aage.myhre@VilNews.com

The quiet resort village Nida is based at the Curonian Spit (Neringa) near the Kaliningrad border, less than one hour’s drive from Klaipeda at Lithuania’s seacoast. With beautiful Baltic Sea beaches on the west side, the large Curonian Lagoon on the east side and the largest sand dunes of Northern Europe on the southern side, this is a truly unique place for a relaxed vacation. You should spend one or two weeks in a self catering fisherman's cottage or a few days in a guest house or hotel. Nida is the place to take it easy!

Here is what a visiting family wrote after their visit:

"We have never visited anywhere that had such a relaxing effect on us as the view from the sun clock on the Great Dune in Nida. The silky-smooth lagoon to one side of the golden spit and the sparkling waves of the Baltic Sea to the other side was breath-takingly beautiful. We did lots of walking, running and cycling including a walk along the Baltic Sea beach from west of Preila back to Nida”.

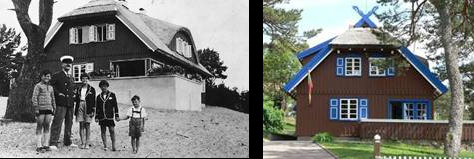

The Nida home of the German writer Thomas Mann,

today the Thomas Mann Museum.

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

Nida tranquility

- Posted by - (1) Comment

Text and photos: Aage Myhre

aage.myhre@VilNews.com

The quiet resort village Nida is based at the Curonian Spit (Neringa) near the Kaliningrad border, less than one hour’s drive from Klaipeda at Lithuania’s seacoast. With beautiful Baltic Sea beaches on the west side, the large Curonian Lagoon on the east side and the largest sand dunes of Northern Europe on the southern side, this is a truly unique place for a relaxed vacation. You should spend one or two weeks in a self catering fisherman's cottage or a few days in a guest house or hotel. Nida is the place to take it easy!

Here is what a visiting family wrote after their visit:

"We have never visited anywhere that had such a relaxing effect on us as the view from the sun clock on the Great Dune in Nida. The silky-smooth lagoon to one side of the golden spit and the sparkling waves of the Baltic Sea to the other side was breath-takingly beautiful. We did lots of walking, running and cycling including a walk along the Baltic Sea beach from west of Preila back to Nida”.

|

|

|

The Nida home of the German writer Thomas Mann, today the Thomas Mann Museum.

The Curonian Lagoon

|

The Curonian Lagoon is separated from the Baltic Sea by the Curonian Spit. Its surface area is 1,619 square kilometres. The Nemunas River supplies about 90% of its inflows; its watershed consists of 100,450 square kilometres in Lithuania, Belarus, and the Kaliningrad Oblast. At the northern end of the Spit, there is a passage to the Baltic Sea, and the place was chosen by the Teutonic Knights in 1252 to found Memelburg castle and the city of Memel (today’s Klaipeda). The Lagoon, formed about 7,000 years BC, is classified as brackish. Water depths average is 3.8 meters. Nida is very beautifully situated on the west bank of the lagoon. It is from here the fishermen go out on the lagoon in the early morning hours to find the catch of the day. This is where sailing boats gather in late summer evenings. It is in the small streets and on the promenade along the lagoon that the good life in Nida takes place. |

|

|

I

took this picture on a warm late summer evening. I had had a very

enjoyable evening with family and friends, and decided afterwards to go for a

walk along the Curonian Lagoon. The silence, peace, and the slow whisper of the

waves from this large lagoon makes an unforgettable impression. The faint

moonlight and the last sailing boats that were heading towards the Nida harbour

made the impression no less impressive. Nida is a place on earth that

simply MUST be experienced...

The local fishermen are still going strong!

Colourful fishermen homes

A sailors’ paradise

A children’s paradise

The Nida sand dunes are high as mountains

|

Nida is located in the middle of the Curonian Spit (Neringa), half way between Klaipeda and Kalininigrad. The Curonian Spit is a long and narrow sand peninsula that separates the Curonian Lagoon from the Baltic Sea. The huge sand dunes here are the largest in North Europe. A walk on the sand-hills on the outskirts of Nida is an absolute must when you're here. You climb up the steep stairs, take off your shoes. Kilometers of hot desert sand lies ahead. To the east you overview the huge lagoon between the Curonian Spit and the Lithuanian mainland. To the west you can see out over the glassy Baltic Sea almost to Sweden. Fantastic!

|

|

The fantastic Nida beaches – at the Baltic Sea

The Curonian Spit is around 3 km wide here at Nida, and it’s very easy to walk from east to west, over the hilltop, through beautiful pine forests, to some of the finest beaches existing at the Baltic Sea. Probably the best in Northern Europe!

|

|

|

Nida tranquillity awaits you!

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - (0) Comment

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - (0) Comment

LITHUANIAN SSR

COAT OF ARMS

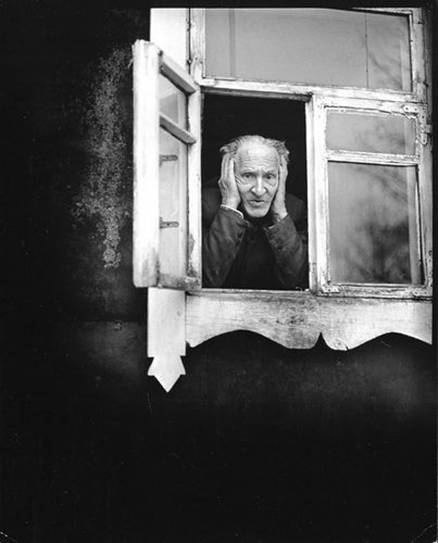

Returning ‘home’ to Lithuania from Siberia

The Last Summer. Zarasai 1968.

PHOTO: ANTANAS SUTKUS.

It must have been quite a shock for the surviving deportees to return ‘home’ from Siberia to Lithuania in the 1950s and 1960s. The country they had loved and cared so much about was now ruled, mismanaged, by Moscow-believing Communists.

Since 1941 more than 300.000 persons had been deported to Siberia, with tens of thousands dying en route to or on the permafrost. Tens of thousands of the country's leading women and men had fled to America and other nations in the west.

The 1950s was the decade when Lithuania's 10-year guerrilla war against the superior Soviet forces had finally come to an end, with the result that 22.000 Lithuanian forest brothers and about 70.000 Soviet soldiers had lost their lives, thus the longest and bloodiest guerrilla war of modern Europe.

Lithuanian daily life during the 1950s and 1960s was characterized by terrifying KGB activities, denunciations, imprisonments and executions without trial, widespread corruption and mismanagement in which most of the good, democratic principles many fine people had fought so hard for during the interwar period were totally forgotten and disregarded.

People felt despair, discouragement, fear ... But also a vain hope - that Western countries would come to liberate their dear homeland from the Soviet tyranny...

Village street, Dzūkija 1969.

PHOTO: ANTANAS SUTKUS.

To see more Antanas Sutkus photos, go to:

http://www.ananasamiami.com/2011/04/photography-by-antanas-sutkus.html

http://www.retronaut.co/2010/05/soviet-lithuania-1960s-1970s/

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

The tragic story of how one third of Lithuania’s population became victims of Soviet terror

- Posted by - (0) Comment

Dalia Kuodyte.

This article is based on a speech manuscript by Dalia Kuodyte, Member of the Parliament, former Director General of the Centre of Genocide and Resistance (LGGRTC).

“In the trains’ cattle cars the passengers were hardly given any food except from a little water and some inedible soup. There was scarcely any air to breathe as everyone was jammed together and the cars had only a few small windows covered with bars. A hole in the floor served as a toilet. Some of the people, especially the infants became sick immediately and died. The bodies of those who died on the journey were left on the side of the tracks.”

The string of tragedies began in August 1939, when Hitler and Stalin concluded a cynical agreement that divided up Central Europe between the two totalitarian countries. According to the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact, Lithuania was to fall into the Soviet zone of influence.

After the outbreak of the Second World War, Lithuania was occupied three times: first by the USSR in 1940, then by Nazi Germany in 1941, and finally by the USSR again in 1944.

Pre-war Lithuania’s position of neutrality on the eve of WWII did not protect the country from its sad fate. According to Lithuanian state institutions, the damage caused by the USSR‘s occupation to the Republic of Lithuania in financial terms is $278 billion. During Nazi and Soviet occupations, including 200,000 Holocaust victims, the losses of the population of Lithuania amounted to 33 percent of the total number of the country's population in 1940. Lithuania lost 1 million people to deportations, executions, incarceration, the murder of the political opposition and forced emigration.

The total number of persons registered as “anti-Soviet elements” reached 320,000 entries. There were teachers and professors, school and college students, farmers, industry workers and craftsmen among them.

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

The tragic story of how one third of Lithuania’s population became victims of Soviet terror

- Posted by - (3) Comment

Dalia Kuodyte.

This article is based on a speech manuscript by Dalia Kuodyte, Member of the Parliament, former Director General of the Centre of Genocide and Resistance (LGGRTC).

“In the trains’ cattle cars the passengers were hardly given any food except from a little water and some inedible soup. There was scarcely any air to breathe as everyone was jammed together and the cars had only a few small windows covered with bars. A hole in the floor served as a toilet. Some of the people, especially the infants became sick immediately and died. The bodies of those who died on the journey were left on the side of the tracks.”

The string of tragedies began in August 1939, when Hitler and Stalin concluded a cynical agreement that divided up Central Europe between the two totalitarian countries. According to the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact, Lithuania was to fall into the Soviet zone of influence.

After the outbreak of the Second World War, Lithuania was occupied three times: first by the USSR in 1940, then by Nazi Germany in 1941, and finally by the USSR again in 1944.

Pre-war Lithuania’s position of neutrality on the eve of WWII did not protect the country from its sad fate. According to Lithuanian state institutions, the damage caused by the USSR‘s occupation to the Republic of Lithuania in financial terms is $278 billion. During Nazi and Soviet occupations, including 200,000 Holocaust victims, the losses of the population of Lithuania amounted to 33 percent of the total number of the country's population in 1940. Lithuania lost 1 million people to deportations, executions, incarceration, the murder of the political opposition and forced emigration.

The total number of persons registered as “anti-Soviet elements” reached 320,000 entries. There were teachers and professors, school and college students, farmers, industry workers and craftsmen among them.

A cargo of 16.246 people were crammed into cattle cars

June 14-18, 1941 were the dark days of the first massive arrest and deportation of the Lithuanian population. A cargo of 16,246 people were crammed into cattle cars. Moscow’s instruction required separate men from their families. So, 3,915 men were separated and transported to concentration camps in the Krasnoyarsk territory while 12,331 women, children and elderly people were transported to the Altai Mountains territory, the Komi republic and to the Tomsk region.

Forty percent these deportees were children below 16 years old. More than half of the deported died quickly. Pregnant women and babies born in the cattle cars were the first victims – they died in the trains. The deportation process was interrupted by the German-Soviet war.

The Soviets resumed mass deportations to Siberia and other eastern regions of the USSR after recapturing Lithuania from Nazi Germany in 1944. The partisan anti-Soviet war for democratic and independent Lithuania began in 1944. Some 22,000 Lithuanian partisans lost their lives in unequal war against the Soviet regular army and NKVD units. From 1949 the armed resistance started to wane. This guerilla war continued until 1953. The last resistance fighter refused to surrender and shot himself in 1965.

Partisans, their supporters and non-armed opposition made up a big group among those who were deported in 1945 – 1947. Another big group of deportees was those who tried to escape service in the Red Army. Ethnic Germans and members of their families, who did not leave Lithuania, were deported as well.

22-23 May 1948: 41.000 Lithuanians seized in their homes and deported

The situation changed in 1948. The most extensive deportation from Lithuania was held on May 22 and 23, 1948. Over these two days 12,100 families, numbering over 41,000 people, were seized from their homes and exiled. In 1948, 50 percent of deportees were accused not of their relations with the armed guerillas. Their official guilt was their social class – they were owners of private farms. In 1949, already two-thirds of the deportees belonged to this category while in 1951 they absolutely dominated the Soviet secret police‘s statistics.

Such change was due to the collectivization campaign in the Lithuania’s countryside. In 1948, the Soviets started to implement mass collectivization, appropriating land and livestock. This resulted in establishment of kolkhozes. In 1950, some 90 percent of land was given to kolkhozes. Mass deportations continued until the death of Josef Stalin in 1953.

How did the typical deportation look? The NKVD broke into an apartment or house and arrested all the family members. The NKVD marched them onto the back of a truck. In the railway station as far as the eye could see there were men and women clutching suitcases and bundles of hastily gathered clothing, the elderly and the disabled searching for places to sit and mothers holding their children, all surrounded by Red Army soldiers brandishing weapons.

Usually, the men were put on separate trains. They usually were transported to prisons and the Gulags (concentration camps) while females, kids and the elderly were deported to live in God-forsaken settlements in Siberia.

In the cattle cars the passengers were given hardly any food except a little water and some inedible soup. There was scarcely any air to breathe as everyone was jammed together and the cars had only a few small windows covered with bars. A hole in the floor served as a toilet. Some of the people, especially the infants became sick immediately and died. The bodies of those who died on the journey were left on the side of the tracks.

After one month the train reached some Siberian center - for example, Novosibirsk. In this case, scores of wagons were transferred onto enormous barges and sent up the River Ob to some remote settlement to live in a bug-infested hut.

The Soviets forced all to work, even as temperatures plunged to -45°C (-49°F)

The Soviets immediately put their prisoners to work. They forced women and teenage girls to march into the forest to cut trees. They worked in deep snow, even as temperatures plunged to minus 45 degrees Celsius. Prisoners cut up trees and later lived in huts made from those tree branches. Sometimes it was so cold they awoke frozen to the ground.

Some deportees collapsed while the guards pushed the others along to another day of work. The collapsed prisoners were then left for dead somewhere behind in the wilderness.

In exchange for their efforts, prisoners received a small amount of hard bread. They were working for food. A full day of hard work was equal to 500 grams of bread. Physically weaker prisoners could only earn 100 grams of bread.

Working prisoners shared their meager rations with those who could not work – the little children, the old and the infirm. Much of the time people had virtually nothing to eat and everyone suffered from constant hunger. Their bodies were swollen and covered with boils caused by malnutrition. Their skin was inflamed by mosquito bites.

The youngest children were affected the most by the harsh conditions and almost all of them were sick. Many of them died from starvation and disease. The elderly followed the children. Those who remained could only struggle to dig graves in the frozen earth.

Gradually, the survivors tried to adjust to life in Siberia. Deportees were permitted to use a patch of ground on which to grow potatoes.

In 1956, Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev decided that deportees should be released. In late 1950s, the survivors started to return to Lithuania.

Deaths of the deportees began to make headlines only in late the 1980s

There is an old and cynical saying that one death is a tragedy, but a thousand are just a front-page headline. Well, of course, deaths of thousands of deportees began to make headlines only in late the 1980s. Let’s look to personal tragedies.

The Šiauliai Aušros Museum has 234 letters of political prisoners, deportees and partisans addressed to their family members and loved ones who managed to escape the Soviet terror in Lithuania.

Lawyer Ignas Urbaitis from town of Šiauliai was arrested on October 6, 1944. He was sentenced for 15 years of slavery work in concentration camps. He died in the Taishet concentration camp in the Irkutsk region in 1952.

He wrote letters to his wife Elena Urbaitienė. In 1947, he wrote, “I’m always walking in the room. Sometimes there is very little room left for it. Sometimes I can make just one step or even less because the room is covered by sleeping or lying bodies. I walk anyway. Other people find it strange. If you can imagine me, imagine me walking backwards and forwards like an animal in the zoo cage. Walking gives comfort to my nerves and heart.”

Urbaitis, like all prisoners of concentration camps, was allowed to write only two letters per year. These letters should be written in Russian because all letters were read by the censors. So, prisoners avoided to write about their sufferings directly because of this censorship.

They found out later that they were eating a friend of theirs who had just died

The survivors of the Gulags and deportations can speak openly now. Former deportee Janė Meškauskaitė says that she and her family was kidnapped by the NKVD one night because her father was member of the ruling Tautininkų Party in the pre-war Lithuania. Her family was put on a train and dropped off at a remote village in the Tomsk region many days later.

They were among the more fortunate deportees, as Russian farmers from Kazakhstan who were exiled in the early 1930s for being to wealthy inhabited the village. They understood her family‘s plight and welcomed them into society. Nevertheless, food was scarce.

“My father once bought some meat from a local crook. He and a friend hid in the woods to cook and eat it so that thugs wouldn’t steal it. They found out later that they were eating a friend of theirs who had just died,” said Meškauskaitė.

Bread was also strictly rationed. “People in our village were allotted 300 grams of flour a day. One time the flourmill broke down so we were simply given whole grains. People were so hungry that they would just eat them uncooked. Of course, most had bad teeth and couldn’t chew them so they would end up undigested in the latrines. Many people would go and collect them, wash them, and make porridge,” she said.

Vytautas Stašaitis was a son of an air force major in pre-World War II independent Lithuania. The family’s spacious house was commandeered by Soviets troops in 1945. His family was exiled to Siberia but he managed to go underground as part of the resistance movement.

Shortly thereafter a supposed friend lured him into a trap. He was asked to supply ammunition for an assassination attempt on the head of the local NKVD. His “friend” gave him up and he was mercilessly beaten during his interrogation.

“I wanted to hang myself in my cell but they prevented me. They gave me 10 years forced labor for sedition and shipped me to Krasnoyarsk to cut trees. They marched us for six days with barely any food and water. Those who couldn’t keep up were shot. When we got to the labor camp they clothed us in the uniforms of dead soldiers. They still had bullet holes and blood stains,” Stašaitis said adding that political prisoners were forced to live together with aggressive Russian criminals who were sentenced for murders and robbery.

We killed the dog with our axes...The dog meat meals were some of the best of my life

Life in Stalin-era labor camps was a dehumanizing experience. The diet allocated to prisoners was less than that required for survival. “As inmates we were chained in pairs. Once my partner and I thought a wolf was attacking us. It turned out to be a guard dog that had broken loose from its chain. We killed it with our axes and buried it in the snow. We returned many times to cook and eat it. Those were some of the best meals of my life,” he said.

Life was not easy for those who survived and returned to Lithuania. Meškauskaitė returned to Lithuania in 1958. “We were placed in an impossible situation. The government required us to register with the local municipality or face renewed deportation. In order to register, we needed an employer, but no one would have courage to give a work to former deportee. I lived and worked illegally for many years with the help of relatives,” she said.

Now former political prisoners, deportees and partisans receive an additional pension, which Lithuanian state finances can manage. Russia, which officially proclaimed inheritance of all international rights and obligations of the USSR, shows no will to pay compensation to them. The Russian state has never said a word asking for forgiveness for the Soviet terror in the occupied Baltic states. However, it was done by Russian dissidents.

Russian Duma MP Sergey Kovalev did it in the Lithuanian parliament in June, 2000. By the way, it is symbolic that in 1974-1975, Kovalev was jailed in the Vilnius KGB prison, which is the Museum of Genocide Victims now, for cooperation with the underground magazine The Chronicle of the Lithuanian Catholic Church.

Kovalev said in his address to the Lithuanian parliament, “It is not true that nations do not commit crimes. The Germans and we should understand it. If we don’t understand our guilt, we can’t expect victory over cannibalistic ideologies. We went to demonstrations in the 1930s supporting mass killings. We are guilty, our Western neighbors. It is my nation that occupied the Baltic countries. Please, forgive us.”

Felix Krasavin, a former Soviet-time political prisoner now living in Israel, spoke to the forum of some 5,000 former Lithuanian political prisoners and deportees in the Vilnius Sport Arena in June, 2000. “Soviet fascism killed many more people than its German brother. The lies of Soviet fascism were much bigger than those of German fascism,” he said.

During their nearly five decades of occupation, the Soviets killed or deported hundreds of thousands Lithuanian, Latvian and Estonian men, women and children. However, this was only a fraction of the tens of millions of people in the USSR and Central Europe whom communists subjected to the midnight knock on the door, arrest, intentionally created famine and starvation, torture, slave labor, or execution.

Communists killed at least 100 million people

Nicolas Werth, French historian and one of the authors of “Livre noir du communisme (The Black Book of Communism)” say the communists killed at least 100 million people in the world. During his lecture in Vilnius University in 2000, he said communism was born in Russia because this country had no democratic experience. During 80 years, one-third of the planet’s population lived under communist regimes. "The closer the country was to the center of repression [Moscow], the more the models of repression were similar to the Soviet ones: public trials, tortures, killings, deportations,” he said.

Virtually no one has been called to account for what was done. The West has chosen to forget these horrors. Nothing of these horrors is taught in their schools. There is no grand museum in Washington, D.C., dedicated to those whose lives were destroyed by the communists.

No Communist Party bosses in Russia have ever been made to pay for their transgressions. Not one labor camp commandant has been forced to answer for his inhumanity. There is no talk of reparations. The Kremlin objects whenever anyone raises questions about the injustice of the past.

The great crimes of Soviet communism are mostly just remembered in the hearts and souls of the victims.

Lithuanians are considering the Soviet terror corresponded to genocide. Most of those deported were doomed - a third of them to a speedy death and the rest to a life of misery in Siberia. One only had to be an honest Lithuanian citizen to face deportation. A lot of work has to be done to clarify world opinion.

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

VilNews e-magazine is published in Vilnius, Lithuania. Editor-in-Chief: Mr. Aage Myhre. Inquires to the editors: editor@VilNews.com.

Code of Ethics: See Section 2 – about VilNews. VilNews is not responsible for content on external links/web pages.

HOW TO ADVERTISE IN VILNEWS.

All content is copyrighted © 2011. UAB ‘VilNews’.

Click on the buttons to open and read each of VilNews' 18 sub-sections

Click on the buttons to open and read each of VilNews' 18 sub-sections

.jpg)