THE VOICE OF INTERNATIONAL LITHUANIA

|

VilNews has its own Google archive! Type a word in the above search box to find any article.

You can also follow us on Facebook. We have two different pages. Click to open and join.

|

Featured black

- Posted by - (0) Comment

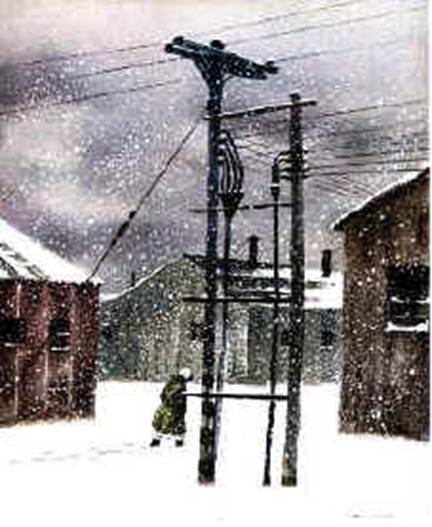

CHRISTMAS IN SIBERIA

A story about a Lithuanian family deported to the Lena River delta.

North Siberia, year 1942

Text: Leona T. Gustaff

“The tents were freezing cold, harsh, and distressing; so, the adults decided to build better living conditions. "We can build barracks," said one Lithuanian, "We can catch the logs in the Lena River." The men waded barefoot into the icy water, caught floating logs, brought them to shore, and built the barracks. They covered the outside walls with snow and ice which they learned would help keep out the frigid temperature. They also found a large iron stove, which they placed in the middle of the building.”

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - (2) Comment

CHRISTMAS IN SIBERIA

A story about a Lithuanian family

deported to the Lena River delta.

North Siberia, year 1942

Text: Leona T. Gustaff

“The tents were freezing cold, harsh, and distressing; so, the adults decided to build better living conditions. "We can build barracks," said one Lithuanian, "We can catch the logs in the Lena River." The men waded barefoot into the icy water, caught floating logs, brought them to shore, and built the barracks. They covered the outside walls with snow and ice which they learned would help keep out the frigid temperature. They also found a large iron stove, which they placed in the middle of the building.”

|

Laima's Story

The house was warm, secure, peaceful. The window drapes had been closed tight to shut out the rising sun. On June 14th in 1941 we were not aware of the tragedy about to enter our lives. A thick, fluffy comforter covered me and kept me safe. Tėtė and Mama slept quietly in the adjacent room. Algis, my three-year-old brother, was in sound slumber in his trundle bed. Suddenly, at 5 a.m., sharp staccato raps at the entrance of our home aroused us. "Guzevičius, wake up! Let us in! We are the militia!"

Tėtė grabbed his robe and slippers and rushed to the front entrance with my Mama, brother and me running close behind. When he opened the door he encountered two men standing on the steps leading into the house. One was dressed in a Russian military outfit; the second was a friend, Dabulavičius, who lived nearby in the village of Brazavo. "Labas," Tėtė, startled and not prepared for what was to follow, greeted the men. The military man, a member of the Russian armed forces, grabbed him by the shoulders, pushed him back into the room, swung him around quickly, clasped his hands to his back, and shackled him with metal hand-cuffs. My brother and I were frightened and bewildered. We were sobbing aloud as Mama pulled at the arms of the soldier and begged him to tell her of what my father was guilty.

"Dabulavičius," she pleaded, "Please tell them not to do this. Stasys has never hurt anyone. He is a good man and does not deserve this kind of treatment. He has even lent you a large sum of money recently so that you could build an addition to your home." Dabulavičius stood by silently and turned his head away so that he would not have to look at my mother.

"Tylėk!" The soldier, pushing Mama aside, ordered her to be silent. "Pack whatever you think the entire family will need for a long journey. Your baggage must be less than 120 kilograms."

In the first year of Soviet occupation, from June 1940 to June 1941, the number confirmed executed, conscripted, or deported is minimally estimated at 124,467: 59,732 in Estonia, 34,250 in Latvia, and 30,485 in Lithuania.

The Times At that time the Soviet Union was in total control of Lithuania. Russian military leaders were aware that 175 divisions of the Third Reich's Wermacht were advancing toward the Soviet Union's western frontier. The soldiers would have to travel through Lithuania.

There had been rumors that Bolshevik militia was gathering educated Lithuanian men and army leaders to incarcerate them in prison or exile them to a foreign land. In order to receive gifts from the military or, in some instances, to save their own lives, neighbors had been approaching the Soviet officers and volunteering evidence of conversations that they had witnessed of discontent with the political regime in power. These were generally trumped up falsehoods. Tėtė then realized that his friend had conjured up treacherous untrue charges about him. Only eight days later, on June 22, the Germans attacked the Soviet Union forcing the Red Army to withdraw from Lithuania. Unfortunately, we were already on a desperate journey to an unknown destination.

Tėtė, my father, was a teacher in the Kalvarijas district. He was born in 1894 in Suvalkija, not far from the town of Punskas, the third in a family of eighteen children, nine of whom were either still born or died soon after birth. He had attended Primary and Secondary schools in Lithuania, received his university education in Russia and returned to Lithuania to teach in Kalvarija. He spoke six languages -- Polish, German, Russian, French, Jewish, Lithuanian -- was the owner of an extensive library with thousands of books, and had founded and promoted new elementary schools in the Marijampolė district.

Active in the community, a leader in the Kalvarija area, he had organized and taught both children and teenagers many different traditional dances. He enjoyed farming, fertilizing the land, and planting seeds to grow potatoes, carrots, and cabbage. He also propagated apple trees. He never imbibed liquor, despised alcoholics, and launched programs against alcoholism.

Tėtė was 33 years old when he married my mother, who was only seventeen years of age. But Mama possessed great physical strength, loved to read, and had lively intelligent conversations with him. She and Tėtė together had purchased a home in Trakėnai from a German nationalist who was returning to his country.

Trakėnai is located about five kilometers south of Kalvarija. It initially had been a large German estate, but eventually was divided into small parcels of land for German families. They bought the property, which consisted of a home and barn with land for farming. Each month they sent a sum of money to the original proprietor, who according to country laws, was the true owner until the entire amount of the sale was paid.

The Beginning of the Journey Mama quickly gathered warm clothing and made small bundles for my brother and me to carry. She snatched the feather comforters from the beds and collected coats, sweaters, socks, and boots. She packed potatoes, cheese, sugar and flour, which she and my father carried. Soon, a truck filled with other Lithuanian families roared to a stop in front of our home. Mama, Tėtė, Algis, and I climbed into the back of the vehicle and searched for an area to put our hurriedly collected bags. My parents held us tight and comforted us as they wiped away our tears. The truck continued on its route until we reached Kalvarijos Railroad Station.

When we arrived at the station we were surprised to see a large group of people who also carried bundles of hastily collected clothing, food, and bedding. There was noise and considerable agitation. Children cried, sobbing aloud. People talked incessantly, looked for friends, made sure certain family members were not separated, and asked each other if they knew where they were going. Everyone was frightened. No one knew the answers.

Tėtė met a friend. "Ulevičius, what is happening here?" "I'm not sure, but haven't you heard the rumors?" "That educated Lithuanian men would be put into prison or exiled to Siberia? Yes, I had heard but it is difficult to believe that Communists would be so cruel." "Speak softly, my friend, so as not to be overheard. We must be careful. We cannot trust anyone." We were pushed into straight lines and commandeered into freight cars -- actually into cattle cars -- that formerly had carried farm animals from the villages to the cities. People were jammed together. Soldiers shoved more men, women, and children into already overcrowded cars. Everyone looked for an area on the floor where they could put their belongings and perhaps sit down. My parents found a small spot where we could huddle together and keep our bundles of clothing and blankets close to us.

Cattle wagon used for deportation.

The Train of Horrors The train began to move slowly and then picked up speed. Trapped in boxes with boarded up windows we moved through our beloved nation quickly. We could only imagine the clear natural lakes, boggy swamps, small working farms, and forests of birch, pine, and spruce trees that we passed. I don't believe any of us realized that this would be our last journey through the Lithuanian countryside for many years. How could we possibly know that some of us would never see this land again but would die and be buried in strange, inhospitable territory where we would suffer bitter cold, hunger, and absence of the ordinary needs and comforts of our existence?

We were thirsty when we made our first stop at Kaunas. Crying children begged for something to drink. "Look, they're bringing water," a woman on the train shouted. She had noticed a soldier carrying a pail of water and walking towards our train. Everyone rushed to the door that was a little ajar.

Mama reached out to take the pail of precious water from the soldier but he, fearing she wished to escape, angrily banged shut the door, which hit her on the head and knocked her down. She fell to the hard floor into a dead faint. "She did not awaken from this unconscious state for the next five hours." my father told me years later. Until the end of her life she had very painful headaches.

From Kaunas the train began to move slowly towards the Russian border where for the first time we were given food: watery gruel and a small piece of black bread. Traveling in a daze suspended by time, we learned we were on the Trans-Siberian railway and feared we were on the way to Siberia.

Years later Onutė Garbštienė, who was also deported in 1941, published her diary, which described some of the difficulties we had encountered:

"Suddenly the hammering of axes echoed down the length of the train. We shuddered as if hit by a charge of electricity! They were boarding up the windows, so the "wild beasts" wouldn't escape from their cages. Some other people climbed inside. They made holes in the walls, to the outside, and also cut a hole in the floor, for our toilet. Everything was so degrading, horrifying, and shameful. Who has ever heard that men and women, crowded into this single area, had to take care of their personal needs in front of each other!

We got used to the shame but not to the stench. The stench was unbearable because many, especially the children, were suffering from diarrhea caused by drinking contaminated water. Not everyone was able to make it directly into the hole. Soon the edges became encrusted with excrement. We couldn't even sit down. We started using a chamber pot, but the stench was even worse. Later we begged and were given permission to take care of this matter wherever we stopped. All shame evaporated! Everyone would squat under the cars and relieve themselves. Constipation was a problem. Suddenly: "Hurry up! Get back inside!" Everyone would run back to their assigned cars with their clothing in disarray! And this went on for the duration of the trip."

Our journey lasted three weeks. Parents were exhausted. Children were tired, moody, and restless. Everyone slept on whatever makeshift accommodation they could make on the floor. Some slept on their baggage. Some were fortunate to have blankets or feather comforters. The daily ration of watery gruel and small slice of rye bread was not enough to satisfy hunger, and many were ill. The perilous trip posed severe difficulty for infants and some died in their grieving mother's arms. Soviet guards tossed them into the woods without benefit of a burial.

The First Stop Eventually we reached the Altay, a sparsely populated mountainous territory in South Siberia, close to Northwest Mongolia, China, and Northeast Kazakhstan. About three times the size of Lithuania, it contains a dense pine forest, which extends into the Altay Mountains. We lived there for the entire winter.

Mama and Tėtė were forced to walk about five kilometers through dark forests to the trees they were ordered to cut. The soles of their boots were worn through, and they covered their feet with rags to help them suffer the ice, twigs, and other debris they walked through on their tortuous journeys. Tėtė was not accustomed to such labor, and each evening his body was filled with pain; his fingers so frozen that he could not bend them. He longed for his library of books. Newspapers, journals, or written materials of any kind did not exist among these people. The only news we received was by word of mouth -- sometimes hopeful, sometimes sad, but always difficult to believe since the source was unknown. We were still fed only bread and watery soup.

We Move On In 1942, at the first signs of summer, we were gathered into trucks and transported to the Lena River, where we were forced to clamber into large barges, heavy wired cages that had been built to transport prisoners. Armed guards patrolled us constantly.

The adults again began to wonder where we were going. "Perhaps we are going to America," said Mr. Abramaičius, the father of a family we had befriended while living in Altay. We were not taken to America but instead, we entered a hellish situation; recollections of which sicken our hearts and spirits and we don't want to remember.

Slowly we sailed down the Lena River. We passed 'taiga' -- forests of pine, larch, spruce, and birch. We fought legions of biting insects, mosquitoes, and gnats. At times we caught sight of reindeer. "Those woods must be full of mushrooms," Abramaičius mentioned to my father. The thought of this delicacy that flourished in the birch woods in our native land brought a sense of sorrow and longing.

We traveled until we reached Trofimovska, a fishing village on the river near the Arctic ocean, not far from the Laptev Sea. We settled in the town of Tiksi. The adults were ordered to pitch tents, the only shelter available. Winter temperature dipped down to minus 40 degree F; summers seldom reached plus 50 degree F. Our bodies were not conditioned to live in severely cold climate.

From Trakėnai, Lithuania to Tiksi, Siberia, a journey of 8.000 km (5,000 miles).

We were fortunate that Mama had taken feather comforters so that we were able to weather the cold somewhat. Others did not even have blankets. Many became ill and quite a few passed away from malnutrition and the frigid environment. Entire families died. The dead were interred in the unfriendly foreign soil. We hoped that someday their bodies might be returned to their beloved Lithuania.

Daily Life Continues The tents were freezing cold, harsh, and distressing; so, the adults decided to build better living conditions. "We can build barracks," said one Lithuanian, "We can catch the logs in the Lena River." The men waded barefoot into the icy water, caught floating logs, brought them to shore, and built the barracks. They covered the outside walls with snow and ice which they learned would help keep out the frigid temperature. They also found a large iron stove, which they placed in the middle of the building.

About 10 or 15 families moved with us into the barracks, but we were not destined to be comfortable very long. Soon, we were attacked by a common enemy found all over the world -- lice! We found them everywhere -- in our beds, on the floors, in our clothing. They attacked our hands, our faces, and our legs. We found them in our hair and all over our bodies. No one was safe from the lice. In Trofimovska there was nothing available to help us get rid of them. We had to kill them with our own hands.

The only food available was fish from the frozen Lena River. Mama and Tėtė organized a group of Lithuanians into a fishing brigade. After drilling a few holes in the ice, they'd put bait on lines, which they lowered into the openings. They sat for hours waiting for signs that fish had snatched the bait, and we had more substantial food to add to our meager supply of bread.

During the second winter in Trofimovska, weak from hunger, I was not able to walk, and I lay in bed for two months. My brother Algis was also in poor health. His teeth began to decay. More Lithuanians died from the hunger and cold. I don't know how we were saved from death.

I remember that Mama sold her wrist watch to a Jakutian native for 30 kilos of black rye flour. She made 'lepioskas', and as we ate the mealy pancake we became stronger. Sometimes Tėtė still caught some fish, but eventually the Russian brigadier leader did not permit him to bring the fish home. This was our most difficult winter. We never had enough to eat, and we were always cold. Lithuanian settlement in Siberia.

Lithuanians deported to Trofimovsk in the region of the Laptev Sea, an area with permafrost north of the Polar Circle. The photo is from 1949. These deportations took place in 1941. In 1942-43, a third of the deported people died, mainly children and elderly people. Photo: The Museum of Genocide Victims, Vilnius, Lithuania.

Uprooted Again In the spring, we were taken to the Siberian Islands to fish for the Communist regime. At first we lived together with the Abramaičius family in a 'yurta', a collapsible shelter built from logs and canvas. The next year Tėtė and I built a 'yurta' for our family to live in separately and alone.

Tėtė began to barter the fish he caught for flour, and mama continued to make 'lepioskas'. Tėtė and Mama fished every day but they caught very few fish. Tėtė's health was failing, and he got tired very quickly. He had been diagnosed with a hernia in Lithuania. Since he was unaccustomed to the rigors of this difficult life, he suffered more intensely each day.

We lived on the islands for two years when suddenly we noticed that the Jakutian native brigades were leaving the area. Fish were also disappearing; they swam elsewhere. The Jakutians had the inner sense to know when the fish would leave the islands, and they followed the fish to their new destination.

The Lithuanians also began to look for ways to leave the islands. Widows with children were given permission by the Communists to go to Jakutsk, a major city almost a thousand miles south on the Lena River. Tėtė and Mama decided to travel to the Baluno region and settle in the village of Tit-Ary. We were still not far from the Laptev Sea. Tėtė spoke Russian very well, and he was fortunate to receive employment as a school manager in Tit-Ary. Native teachers taught writing poorly, and he helped many students formulate good notebooks. For the first time in our exile to Siberia I could go to school. I was so happy that I finished two years of classes in one year.

We Say Goodbye In 1945, we heard that the war had ended. Tėtė wrote a letter to his brother, Joseph, who had emigrated many years earlier to America and lived in a suburb of Boston, Massachusetts. He was delivering it to the post office when he was accosted and beaten severely by Communist Commandos who resented the fact that he had a brother in the United States. Tėtė became seriously ill. He needed major surgery but the only medical assistance available to the exiles was an apprentice to a veterinarian.

We made plans to search for a surgeon. Tėtė and I boarded a barge that was returning to Jakutsk after unloading food and other provisions. We sailed up the Lena River to our destination. The journey lasted one week. Since Tėtė was a Lithuanian 'tremtinys' (exile), he didn't have the necessary papers for permission to enter. When we arrived at Jakutsk, we were too frightened to go into the city. We were forced to return to Tit-Ary without the benefit of seeing a skilled physician.

Tėtė's health became weaker each day. The medication given to him by the veterinarian's assistant would not relieve the pain. His concern that he was not strong enough to gather provisions for his family hastened the end of his life. Mama was devastated. Each day they conversed and planned about where she would go should his life be terminated. Although his health had deteriorated, he was a comfort to us and we looked to him for moral support. He died in Tit-Ary in 1948 and was interred there in the deep icy tundra. He was fifty four years old.

Lithuanian funeral in Siberia.

We Escape After the death of my father, Mama, Algis, and I escaped to Jakutsk, as my parents had planned. Seven years previous, when I had been seven years of age, we had been forced by the Communists to leave our comfortable home in Lithuania and travel to Siberia -- seven difficult, miserable, unhappy years for which we questioned the unfortunate circumstances which propelled us into this strange life.

We reached the city of Jakutsk and were compelled to register our arrival. The general was not inclined to let us stay, and he told Mama, "If you do not find a job within seven days you must return to Tit-Ary."

Jakutsk is the capital and major city of the Jakutia region. Similar to a large Soviet city, it had many schools, the Luovo Cooperative Institute, a theater, and industry that had developed during the war. Its great distance from Moscow gave it the ability to make crucial weapons and military supplies far from the impact of bombs and other artillery. The weather is the coldest in the world, and buildings are built on piles driven into the permafrost. In 1948 the majority of the population was Russian, many of which were exiles, including some from East European countries.

We searched and found Lithuanian exiles who had settled in Jakutsk earlier. Willing to help us, they informed Mama about a manager at a glass factory who would hire her. Shortly after mama began to work in the factory, I was also given employment in the same building.

I wanted to continue my education; so, I returned to school and finished the Tenth Form at the Middle School after completing two grades in one year. We learned to speak Russian in school and on the streets, but we always spoke Lithuanian in our home.

I loved to sing and wished to study music but I couldn't get a piano; so, I entered the Jakutsk Technical Cooperative School and studied accounting. I was a good student and worked diligently. The administration advised me that I was one of two graduates with the highest scholastic marks, and I would receive a scholarship to Luovo Cooperative Institute. But Communist Security Officials informed me that I could not take advantage of the education given at the Institute. The honor was not available to Lithuanian exiles.

Lithuanian forestry workers in Siberia.

Hoping to See Lithuania In 1953, Stalin died and the Communists began to slowly allow children and teachers to return to Lithuania, but I was ordered to work as a bookkeeper in the city of Jakutsk. After two years I was awarded a vacation and permission to travel to Lithuania.

I wrote to my father's brother, Pranas, who resided in Kaunas to tell him the good news. My Uncle Pranas was a respected Chemical Engineer who had been incarcerated in jail by the Communists for two years but never had to leave for Siberia. He invited me to stay with him and sent me the money I needed for the journey.

In 1956 I was in Kaunas. I traveled on the same Trans-Siberian Railway route I had taken from Lithuania to Siberia fifteen years ago. But this time I saw the clear natural lakes, boggy swamps, small working farms, and forests of birch, pine, and spruce trees that I could only imagine on my first and only trip from the country of my birthplace. I cannot begin to explain the immense joy and pain I felt; joy that I lived to enter Lithuania again and pain that my father would never return to see his homestead, his apple trees, or the schools where he taught.

If Tėtė were with me, he would not have recognized his beloved Lithuania. The ruling Soviet party dictated and controlled all public and private actions in the land. Politics, the radio, accounting, education were conducted in Russian. In the schools the Russian language was predominant. No Lithuanian was heard on the radio. Religious education was forbidden, and free expression of our native tongue, songs, and holiday celebrations was not allowed. Lithuanians worked within the Communist system in order to survive.

The family home in Trakėnai had been leveled and rebuilt twice. Tėtė had given his important documents to his brother Pranas to retain in his possession when we were forcefully sent to Siberia. Unfortunately, Pranas’ home was also damaged during the war and all papers had been burned or destroyed. I wondered what would happen with our house and land. Strangers had taken residency there.

Still, I preferred to remain in Lithuania. I didn’t want to return to Siberia, but my documents were only for a three-month sojourn. It was a difficult and terrifying time. A friend suggested that I lose my pass but I was afraid. I was fortunate. Uncle Pranas' wife's sister was married to a Russian General, and she urged him to petition the Chairman of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet in Lithuania, Justas Paleckis, to give me leave to stay in my country.

All the documents had to be issued in Vilnius; so, I traveled there to stay with the General. He felt sorry for me, and indicated that he himself would go to Moscow to get permission for me to remain in Lithuania if Justas Paleckis refused. To my joy, I was awarded an extension of my vacation for one entire year.

At the end of the year I was allowed to remain in Lithuania, but I was asked to leave Vilnius. I didn't leave Vilnius and concealed my residency by omitting to register my presence. Kipras Petrauskas, a renowned composer of music with important influential friends, admitted me into his home. I resided with his family and was warned to hide when men of the militia came to visit. Eventually, after some time, I ventured into the market place and found work as an accountant in a ‘prekyba’ (business shop). Gradually I began to work with other 'prekybas' and after thirty-six years I was the accountant for all the ‘prekybas’ in Vilnius.

Didzioji g. in Vilnius, 1953.

A Family Reunited

Three years after I had returned to Lithuania, I saved enough rubles to send for my mother. She traveled on the same Trans-Siberian railway that had taken us to Siberia. Her delight in her return to her native land was the ability to buy fresh fruits and vegetables that were difficult to purchase in the tundra. Since she learned to speak Russian in the country of her exile, she had no difficulty communicating with the language demanded by the Communist regime. But we still spoke Lithuanian in our home.

Three years later my mother and I welcomed my brother to Lithuania. We all recognized that it was not the same country we had been forced to leave many years earlier. But we were in the land of our birth, the land of our ancestors. We were home among friends and relatives.

Lithuanian cemetery - Irkutsk Region.

|

The face of cruelty –

Lithuania’s quisling

Antanas Sniečkus, leader of Lithuania’s Communist Party for the period 1940-1974 sent tens of

thousands of his own countrymen to inhuman suffering and death in Siberian labour camps.

Antanas Sniečkus, the first secretary of the Communist Party of Lithuania (from 15 August 1940 until his death in 1974), is said to have been the initiator of the first mass deportations of Lithuanians in June 1941. He even had his own brother, with his family, deported to Siberia, where his brother died.

Antanas Sniečkus was born in 1903, in the village of Būbleliai, 60 km west of Kaunas. During the First World War, his family fled to Russia where he observed the Russian revolution of 1917. In 1919, his family returned to Lithuania; by 1920 he was already a member of the Bolshevik Party. In the same year, he was arrested for anti-governmental activities. He was released from prison on bail, but fled to Moscow, and became an agent of the Comintern. In Moscow, he earned the trust of Zigmas Angarietis, and Vincas Mickevičius-Kapsukas, and became a member of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Lithuania. In 1926, the Comintern sent Sniečkus to Lithuania to replace the recently-executed Karolis Požėla as head of the banned and underground Communist Party of Lithuania.

From 1926 to 1930, he engaged in subversive activities in Lithuania, and was again arrested and imprisoned for them in the Kaunas Prison in 1930. In 1933, Sniečkus was released in exchange for Lithuanian political prisoners held in the USSR. In 1936, he returned to Lithuania. In 1939, he was arrested again, and sentenced to eight years in prison.

After the Soviets invaded and occupied Lithuania, Sniečkus was released from prison on 18 June 1940, and became the head of the Department of National Security. Foreign Affairs Commissar Vladimir Dekanozov, arrived in Lithuania a few days earlier on June 15, 1940, to organize the incorporation of Lithuania into the Soviet Union. As party secretary, Sniečkus issued Vladimir Dekanozov’s orders in the party’s name.

Sniečkus helped create an atmosphere of terror prior to the elections of the newly established, by the Soviet authorities, People's Seimas in July 1940. Only the Communist Party of Lithuania and its collaborators could nominate candidates. People were threatened in various ways to participate in the elections, but the results were falsified anyway. 21 July 1940 the People's Parliament, declared that the Lithuanian "people" wanted to join the Soviet Union, and 3 August 3 1940, the Supreme Soviet of the USSR incorporated Lithuania into the Soviet Union.

The process of annexation was formally over and the Lithuanian Soviet Socialist Republic was created. From 15 August 1940, until his death in 1974, Sniečkus remained the First Secretary of the Lithuanian Communist Party.

34 years of terror and atrocities against his own people had finally come to an end.

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

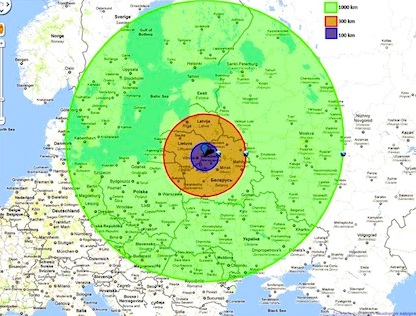

Kaliningrad and Belarus nuclear power plants. (NPP1 and 2)

on the border of Lithuania.

Prepared by:

Dr. Stan (Stasys) Backaitis, P.E., SAE Fellow1

Lithuanian American Council

One NPP containing two reactors, will be situated in Astravets, Belarus, approximately 20 km (12 miles) east of Lithuania and about 50 km (31 miles) from its capital city of Vilnius. The other set of two reactors will be constructed in the Kaliningrad enclave approximately 10 km (6 miles) south and west of Lithuania’s border. (The Kaliningrad enclave is a small patch of Russian-administered land wedged between the European Union nations of Poland and Lithuania.) In case of a nuclear disaster, the two NPPs pose a grave danger to Lithuania and other North-European countries.

Zones of nuclear endangerment by the Kaliningrad nuclear power plant.

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

Kaliningrad and Belarus nuclear power plants. (NPP1 and 2)

on the border of Lithuania.

One NPP containing two reactors, will be situated in Astravets, Belarus, approximately 20 km (12 miles) east of Lithuania and about 50 km (31 miles) from its capital city of Vilnius. The other set of two reactors will be constructed in the Kaliningrad enclave approximately 10 km (6 miles) south and west of Lithuania’s border. (The Kaliningrad enclave is a small patch of Russian-administered land wedged between the European Union nations of Poland and Lithuania.) In case of a nuclear disaster, the two NPPs pose a grave danger to Lithuania and other North-European countries.

The Kaliningrad and the Belarus NPPs, by being built on the borders of Lithuania, place the entire country in a ominous nuclear vise (Figure 1). A nuclear failure at either plant would expose large and densely populated areas of Lithuania to deadly radiation and nuclear poisoning. The NPP in Belarus would impact the entire metropolitan Vilnius region and thus more than a third of Lithuania’s population (Figure 2). A failure in the Kaliningrad NPP would place approximately a fourth of Lithuania’s population at risk. (Figure 3). In total, more than half of Lithuania’s population would be subjected to nuclear-based devastation in the event that both plants experience concurrent nuclear disasters. While such simultaneous NPP failures may at first appear to be remote, they are not beyond the realm of the possible. One need only consider Chernobyl and the 9/11 attack as well as human error, negligence, defects in planning and construction, acts of terror, war, seismic activity and aircraft crashes.

Lithuania is deeply concerned in that Russia and Belarus have not coordinated or reconciled the site selection with Lithuania from a safety standpoint. Lithuania deems the proposed sites as major and unnecessary risks to its survival not only in terms of potential radiation poisoning of its population, but also the consequent devas¬tation of its land and urban areas. Any new nuclear plant construction must consider the consequences of the meltdowns in Chernobyl in 1986 and Fukushima in 2011. According to Gregory Yaczko, Chairman of the Nuclear Regulatory Commission, in his report to the American Association for the dvancement of Science Symposium in 2011, the area affected by the Fukushima nuclear disaster covers an 80 km radius, and at present it cannot be established when the displaced inhabitants could return to their homes.

Nuclear incidents do not recognize state or country borders, or even great bodies of water. As a case in point, Sweden suffered radioactive cesium contamination from the Chernobyl disaster even though it was some 500 miles distant from the site, including 200 miles over the Baltic Sea. It stands to reason that such volatile objects should not be constructed on the borders of a neighboring country exposing it to a risk of mortal danger. To preclude such an occurrence,

international conventions on nuclear safety require transparency, bilateral and multilateral review, and due process leading to a resolution of disputed issues. The parties of origin, in this case Russia and Belarus, are mandated to adhere to internationally established nuclear safety standards as established by the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA).

Notwithstanding Lithuania’s numerous requests directed to Russia and Belarus for the site selection criteria as to both NPPs, neither Russian and Belarusan authorities have produced any substantive data but for self-serving conclusory assertions that they are in compliance with safety standards. In contrast, IAEA and Espoo conventions require that there be compliance with clearly stated processes before the construction of new NPPs. They include: justification, generic design assessment, strategic siting assessment, national policy statement, licensing and planning. The sequence of these internationally established procedures are logical and necessary, and should be strictly adhered to and not be preemptively dismissed by the parties of origin.

Figure 2. Zones of nuclear endangerment by the Belarus nuclear power plant.

Figure 3. Zones of nuclear endangerment by the Kaliningrad nuclear power plant.

Summary of Issues

The Lithuanian American Council (LAC) is concerned that once the construction of the Belarus and Kaliningrad NPPs has commenced, Lithuania will be confronted with an irreversible situation. LAC agrees with Lithuania’s authorities that NPPs planned at the currently designated Belarus and Kaliningrad sites, constitute a threat to Lithuania’s existence. The following considerations summarize our concerns:

1.Consequences from structural damage to the reactors caused by seismic disturbances, external impacts, and acts of terrorism;

2.Questionable structural, electrical and mechanical integrities of subject NPPs;

3.Sufficiency of water and other physical resources needed to contain the effects of a nuclear disaster;

4.Safety of Lithuania’s population in the event of minor and major NPP failures;

5.Provisions for notification of emergencies and evacuation of the populace;

6.Effects on water, vegetation and habitat over the entire land area of Lithuania, and Kaliningrad and Belarus regions;

7.Availability of funds to cover shelter and subsistence for evacuees;

8.Plans and provisions to resolve long term contamination effects;

9.Short term and long term storage and removal of spent nuclear fuel;

10.Consent of the populations at risk

1. Consequences from structural damage to the reactors caused by seismic effects, external impacts, and acts of terrorism

The recent Fukushima nuclear accident has focused the international community on the need to evaluate the risks and consequences of all possible scenarios potentially placing nuclear reactors at risk. Notwithstanding this international consensus, Belarusan and Russian authorities continue to ignore, or at best minimize, the risks of earthquakes on the reactors at the proposed NPP sites.

Belarus in the EIA states that:

There is a zone in the southwest part of the region (…) In 1908, according to the archives and literary sources, a big earthquake took place in Ostrovetsky district with the epicentre being near the settlement of Gudoai. It measured 6-7 on the MSK-64 scale and the effects were substantial in magnitude.

However, in the following sentence, Belarus authorities assert that the “….maximum probable earthquake magnitude would not be expected to exceed a level of 5,” based on their own self-serving and unsubstantiated evaluation that there exists a “…low probability of stronger earthquake.”

Russia has not made any public earthquake assessments in the Kaliningrad region, even though in the immediate vicinity of the proposed NPP a Richter 5 level earthquake was recorded as late as 2004.

Furthermore, Ivan Grabelnikov, the chief engineer overseeing the Kaliningrad NPP project, in the course of a technical conference conceded that neither the VVER-1200 reactors nor its buildings have undergone simulation testing with respect to potential aircraft crashes at the site. On the other hand, nuclear facilities operating in Western Europe are currently required to substantiate that new reactors will be able to withstand such impacts. A direct plane crash into a reactor containment building would not only destabilize the reactor, but would also jeopardize the integrity of the onsite storage facilities housing the spent but still radioactive nuclear fuel. To the best of LAC’s knowledge, no protection is provided against such incidents at either the Kaliningrad or Belarus sites. This is especially disconcerting as there exists a major north-south flight corridor over the planned NPP site in Belarus. It is also a matter of record that in 2005, a Russian fighter jet actually crashed in Lithuania near the planned Kaliningrad NPP site.

2. Questionable structural, electrical and mechanical integrities of subject NPPs

Recently Russian authorities claimed that comprehensive stress tests (allegedly applying standards beyond those adopted by the EU) were performed on all NPPs in the Russian Federation with positive results. However, the structural collapse of the Leningrad-2 NPP containment building in the summer of 2011 raises questions about the veracity of such claims and the validity of the tests. Russia’s own internal reports confirm that equipment failures at nuclear power plants are fairly frequent because of “…such underlying causes as mismanagement, flaws in maintenance organization, manufacturing and design defects.”

Furthermore, the VVER-1200 reactors belong to a completely new Russian reactor series, dubbed as AES-2006. They are touted by Rosatom as the latest and safest technological achievement. But the fact is, this reactor model has no extensive history of operation to substantiate such safety or reliability claims. During the construction of a similar reactor in China, the Russian contractor received repeated complaints from the Chinese concerning the quality of materials used and equipment employed. These concerns eventually led to a significant delay in the NPP construction. During the first year of operation, the reactor in China had to be stopped twice to deal with unplanned maintenance procedures.

Both, the Russian Federation and Belarus ought conduct risk and safety assessments for these particular reactors applying IAEA test and evaluation protocols and provide documented assessments for review by the European Commission as well as to the Republic of Lithuania, as the principle affected and aggrieving party.

3. Sufficiency of water and other physical resources needed to contain the effects of a nuclear disaster

Sufficient water resources are needed at NPPs not only to cool reactors in the course of normal operation, but also to contain nuclear fires and reduce the escape of nuclear contaminants into the atmosphere in the case of an accident. The Fukushima nuclear disaster required several million cubic meters of water merely to limit the spread of fire. During the nuclear fire, even the quantity of water in the large Fukushima cooling basin was insufficient. A significant quantity of water had be pumped directly from the ocean to the site.

Limited water supplies at the Belarus NPP are a particularly critical issue. There are no significant water resources in the region. The nearest sizeable stream that is to provide and fill the cooling basin is several miles away. It is approximately the size of the Rock Creek in Washington, D.C., flowing more in the rainy season and nearly dry during summer droughts. Furthermore, the stream’s water level is some 42 m. lower than the plateau of the terrain of the NPP. This further limits water availability to contain critical reactor events. While the size of the proposed cooling basin is not known, it is obvious that short of creating a very large lake, a limited size cooling basin would not be sufficient to contain a reactor meltdown.

It also needs to be pointed out that down-flowing waters from the nearby creeks merge into the Neris River which is less than 30 miles downstream and meanders through the center of the city of Vilnius. The river, before reaching Vilnius, becomes the principal source of potable water for nearly a million people living in the metropolitan Vilnius area. In the event of leakage or fallout of nuclear contaminants into the area’s waterways, Vilnius and the surrounding area would become uninhabitable and the land unsuitable for agricultural use. It would decimate the wildlife in the region, and for many miles would poison the entire downstream river basin that is situated entirely within Lithuania’s borders.

With regard to water resources for the Kaliningrad NPP, Russia is planning to divert part of the sizeable Nemunas River to fill the cooling basin. The river, 6 miles north of the NPP, constitutes a common border between Lithuania and the Kaliningrad oblast, until it reaches the delta area, some 40 miles to the west. LAC has no knowledge of how much water would be diverted to accommodate the Kaliningrad NPP, the size of the proposed cooling basin, and whether the volume of water would be sufficient to contain a nuclear meltdown. However, it is certain that any down-flowing return of contaminated water from the NPP into the river Nemunas would seriously endanger the downstream part of the entire river basin and the inhabitants living along its shores. Of even greater concern is the ecological impact on the Nemunas river delta, merely 40 miles downstream from the NPP site. The delta area is located entirely within the territory of Lithuania, with water flowing extremely slowly or not at all. Atomic residue from the Kaliningrad NPP would accumulate in significant quantities, creating a cesspool of irradiated nuclear waste. The delta area is not only densely populated, but it is also a major wildlife sanctuary, particularly as a stopover point for migratory birds between Europe’s northern nesting grounds in summer and southern grounds in Africa during the winter season. In case of nuclear poisoning of the delta waters, the entire ecosystem of central Europe would be jeopardized.

4. Safety of Lithuania’s population in the event of minor and major NPP failures

Radioactive materials escaping from a nuclear power plant can have varying effects depending on the type of failure and the distance of populated areas from the failure site. In the case of the Chernobyl disaster, 30 workers died within a month after being exposed to high levels of radiation at that site. Many others, in the thousands, sustained serious injuries from radioactive exposure. Some of them died later, but many suffered ongoing illnesses, traumatized for the remainder of their lives. In the Fukushima radiation zone in the wake of the meltdowns high death rates were recorded among the abandoned livestock. Of the 3,500 cattle that remained in the radiation zone, 2,500 died, and the remaining appear terminally ill.

Large doses of ionizing radiation can cause cell death, while lower doses may interfere with cellular proliferation. Response to radiation depends on rapidity and the portion of the body exposed. Significant illness is certain, and death is possible, when a whole-body dose exceeds 4.5 Gy delivered over a short time interval.

Children and pregnant women are more susceptible to radiation injury because of their higher rate of cellular proliferation. After the Chernobyl meltdown, over the period of 1990-1998, 60% of children tested were found suffering from radiation effects; 1,981 of them were diagnosed with thyroid cancer.

Victims subjected to a high level of radiation either die shortly after exposure (cerebrovascular syndrome) or, if they survive, will sustain incurable longer term damage to their intestines, suffering vomiting and diarrhea, and to their bone marrow resulting in weakened red cell production and eventual onset of cancer.

Lower dose damage in the first thirty days rarely cause immediate danger to human life (GI syndrome), but symptoms of radiation can be felt as chronic fatigue, headache, fever, nausea, vomiting, anorexia, incurable sores, loss of hair, and eventually may develop into leukemia or other forms of cancer. Other effects could include genetic mutation, premature aging, and disorders of the nervous and mental systems.

The toxins and long term effect of radiation poisoning make it imperative that the impacted populace be immediately evacuated from the affected area to assure minimal exposure to radiation. It is also essential that needed medical assistance including medications be held in readiness and be made available to counteract the effects of radiation exposure.

Neither Russia nor Belarus has offered to discuss preparation and provision for such eventualities, and to date, the potential radiological impact of a nuclear accident on Lithuania’s population has not been properly addressed, let alone evaluated, by either of the project sponsors.

5. Provisions for notification of emergencies and evacuation of the populace

Early warning and extensive emergency evacuation provisions need to be established in bilateral discussions and treaties. Lithuania currently has a bilateral treaty with Belarus on early notification of nuclear accidents. Lithuania has also proposed such a treaty with the Russian Federation, but so far it has failed to respond. Furthermore, there are no discussions on how Russia and Belarus would facilitate, in the event of a nuclear disaster, the evacuation of Lithuania’s capital Vilnius and other densely populated areas. In the case of the Chernobyl accident, immediate evacuation of some 120,000 people during the first 24 hours had to be effected. Similarly, the Fukushima accident resulted in the evacuation of 170,000 people within a similar period. Since any Belarus and/or Kaliningrad NPP failures would affect mostly the people of Lithuania numbering in many hundreds of thousands, clear evacuation plans and adequate means to do so must be developed in bilateral agreements as required by the Espoo Convention.

6. Effects on water, vegetation and habitat over the entire land of Lithuania, and Kaliningrad and Belarus regions

In the Chernobyl and Fukushima nuclear disasters, large tracts of land were found to be contaminated. None of the agricultural products, be it vegetation or livestock, were suitable for human consumption. Even now several decades after the Chernobyl meltdown, the soil remains unsuitable for growing vegetation and raising animals.

Inasmuch as a significant nuclear leakage would involve contamination of major parts of Lithuania’s territory, bilateral agreements must be concluded, before any construction work is to commence, on procedures to avoid or minimize damage, and, on methods of compensation, including restitution of contaminated sites to their original condition. A model fund for restitution of contaminated areas has been developed by the United States. It is known as Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation and Liability Act (CERCLA) or Superfund. The model could be used as a basis for negotiation between Lithuania and Russia/Belarus. The statute assures that parties or organizations responsible for contamination are held accountable for costly cleanup and restitution of the contaminated sites.

7. Availability of funds to cover shelter and subsistence for long term evacuees

The Chernobyl accident resulted in some 330,000 people being permanently displaced, sustaining loss of their homes, places of business, and employment. The Chernobyl accident and the measures taken to deal with its consequences have cost the Soviet Union at that time – and later Belarus, the Russian Federation and Ukraine – hundreds of billions of dollars. Today, social benefits are paid to some 7 million people who have sustained harm from by the Chernobyl accident. Such payments are a huge burden on national budgets and, because of their size, in the long run, may not be sustainable.

Similar experience is facing the people of the Fukushima region. Of the 170,000 evacuated, some 70,000 people are unable to return to their former living areas as they are deemed too dangerous for habitation.

Any significant Belarus and Kaliningrad NPP failures involving a major radiation leakage or meltdown, would predominantly impact the people of Lithuania. Accordingly, adequate funds or insurance must be set aside by owners of the reactors and escrowed by a third party to pay for possible long term losses. Considering past experience, reluctance to acknowledge such events and even their severities, and refusal to honor agreements and promises, verbal assurances by the governments of Belarus and Russia to assume financial responsibility are inadequate. This question can only be resolved through ironclad commitments before any NPP construction is started.

8. Plans and provisions to resolve long term contamination effects

The Chernobyl accident involved the discharge of substantial quantities of radioactive substances into the environment. An area of 76,100 km2 was contaminated mostly with high concentrations of radioactive nuclides such as iodine 131, cesium-137 and strontium 90. The contaminations required mass evacuations of people. It disrupted the way of life and economic activity in various parts of Russia, Ukraine and Belarus. In just the first year after the accident, 144,000 hectares of farm land were taken out of use, forestry work was stopped in an area of 492,000 hectares, and most industrial and agricultural enterprises ceased operations in the affected area.

Assuming a uniform circular dispersion pattern within a radius of 70 km., a Chernobyl level accident at the Belarus NPP could contaminate approximately 6,000 km2 (approx. 10%) of Lithuania’s territory by high concentrations of nuclides. The affected area would include the entire city of Vilnius with some 600,000 inhabitants. A Chernobyl level meltdown at the Kaliningrad NPP could affect more than 10,000 km2 or about 16% of Lithuania’s area. Since radiation contamination of buildings and land would have long term effects and prevent their use, agreements must be reached on how the contaminated objects would be restored to their pre-damage state, or what other type of remedies need to be considered. While the likelihood of a Chernobyl-type accident is small, nevertheless, Lithuania’s concerns must be addressed and consideration given to alternative sites.

Minimal acceptable distances from the NPP to Lithuania’s borders must be established and assurances given that drainage and down-flow of any contaminated waters into its territory will be prevented. This all must be determined by mutual agreement between parties before construction of the NPPs commences.

9. Short and long term storage and removal of spent nuclear fuel

Used nuclear fuel is a solid material that is initially securely stored at nuclear plant sites. This temporary storage is one component of an integrated spent fuel management system that addresses all facets of intermediate and long term storing of radioactive nuclear fuel.

Spent nuclear fuel that remains stored at nuclear power plants, is normally contained in steel-lined, concrete pools or basins filled with water. Upon initial cool-off period of some 5 to 10 years, it is transferred to massive, airtight steel or concrete-and-steel containers. Eventually, after several decades the spent fuel rods may be transferred to a permanent geologic repository unless recycled for reuse, or a new technology is discovered for their use in other applications.

The stored spent material, similar to virgin nuclear material used by the NPP, is subject to terrorist attacks, natural disasters such as power failures, overheating due to coolant leakage, destruction by acts of war, and accidental or targeted plane crashes. Any damage to containers and their content can result in a dangerous release of radioactive contaminants. While it may be assumed that eventually spent nuclear materials would be transferred from the Belarus NPP by way of safely packaged railroad containers to some permanent storage sites in Russia, LAC has no information confirming that such will occur.

Of equal concern is the handling and storage of radioactive materials at the Kaliningrad site, since it is less than six miles from Lithuania. LAC has no information as to Russia’s plans concerning the storing of the spent radioactive materials at the NPP site. Neither is there any information on the transportation provisions which will be employed to transfer the spent nuclear waste for permanent storage. Russia’s EIA report on the Kaliningrad NPP provides a statement that a route of transporting the spent materials from the NPP in Kaliningrad to a burial site will be defined in the working documentation. In as much as railroad transport of such materials through Lithuania might not be admissible, the only other way to remove the materials would be either by sea transport or air. Some Russian publications imply that spent nuclear fuel would be transported from the Kaliningrad NPP by the Baltic Sea to the nuclear waste repository in Sosnovy Bor, near Saint Petersburg. However, if such a transport mode would be employed, Russia’s current EIA is silent on possible perils to all of the Baltic sea countries in case of a shipwreck or partial cargo loss.

Even though Lithuania has posed questions to Russia and Belarus on methods of disposal of the spent fuel, the LAC notes that Russia to date has failed to address or even seriously acknowledge this critical issue.

10 Consent of affected public, alternative sites, bilateral agreements

Russia and Belarus are disregarding Lithuania’s objections to the proposed construction of nuclear plants adjacent to Lithuania’s border. The site locations for the nuclear reactors pose a threat to Lithuania’s survival as a nation. Accordingly, the construction of both NPPs are in violation of the Espoo and IAEA conventions.

The Espoo Convention on Environmental Impact Assessment in a Transboundary Context of 1991 addresses the responsibilities of the Parties of origin (project initiators).

The Espoo Convention in Article 2 requires that:

1) The Parties shall, either individually or jointly, take all appropriate and effective measures to prevent, reduce and control significant adverse transboundary environmental impact from proposed activities, and

2) the Party of origin shall provide, in accordance with the provisions of this Convention, an opportunity to the public in the areas likely to be affected to participate in relevant environmental impact assessment procedures regarding proposed activities and shall ensure that the opportunity provided to the public of the affected Party is equivalent to that provided to the public of the Party of origin.

Article 5 notes that:

The Party of origin shall, after completion of the environmental impact assessment documentation, without undue delay enter into consultations with the affected Party concerning possible alternatives to the proposed activity, including the no-action alternative and possible measures to mitigate significant adverse transboundary impact and to monitor the effects of such measures at the expense of the Party of origin.

Article 6 states that:

The Party of origin shall provide to the affected Party the final decision on the proposed activity along with the reasons and considerations on which the decision was based.

Furthermore, the IAEA Commission decision, 1999/819/Euratom, of November 16, 1999, concerning the accession to the 1994 Convention on Nuclear Safety by the European Atomic Energy Community (Euratom) notes that “In choosing the site, one must consider, inter alia, its effect on the safety of the installation and the effects of the installation on individuals and the environment.” It notes further that other contracting parties in the vicinity of the site must also be consulted if the installation is likely to have consequences for them.

While Belarus claims to have presented Lithuania with an environmental impact assessment regarding its NPP, LAC is informed that the Lithuanian government has rejected the assessment saying that questions submitted to Belarus have not been responded to properly, and that claimed public hearings in Vilnius were either a sham or fabrication, and that actually no substantive consultations have taken place.

There was even less consultation with Russia regarding the Kaliningrad NPP. Russia has neither held public hearings nor offered to participate in bilateral consultations despite Lithuania’s request to do so.

It is noted that Constituents in Belarus and Kaliningrad as well as in Lithuania in a series of public demonstrations have repeatedly voiced their opposition to the construction of subject NPPs.

LAC is concerned that the NPPs’ site selections were based on political considerations rather than on Espoo and IAEA established criteria requiring that the selection be grounded on sound environmental criteria and particularly by addressing the safety of the population situated near the site.

Lithuania has filed a complaint with the secretariat of the Espoo Convention stating that Belarus, contrary to its assertion, has not complied with mandated procedures of the environment impact assessment process, as is required by the Espoo Convention. Lithuania has also submitted a similar note to the secretariat of the Espoo Convention on the deficiencies in Russia’s response regarding the proposed NPP in Kaliningrad. Russian authorities blatantly assert that they are in compliance with Espoo and are following its provisions, notwithstanding its failure to enter into any consultations with Lithuania.

Conclusion

Based on the analysis presented here regarding the two proposed NPP sites, it is amply clear that the EIA process has not been satisfactorily completed and that the requirements of the Espoo Convention have not been fulfilled by Russia and Belarus. Considering the potentially severe consequences for Lithuania in the event of a nuclear failure at either the Belarus or the Kaliningrad reactors, the international community must respond and insist that established nuclear standards be adhered to. LAC urges the United States legislative and executive branches to address Belarus and Russia’s governments insisting that they cease any further activity on these projects until the EIA process is accomplished and all issues are resolved in accordance with international nuclear safety standards, principles, and conventions.

Prepared by:

Dr. Stan (Stasys) Backaitis, P.E., SAE Fellow1

Lithuanian American Council

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - (0) Comment

CHRISTMAS IN LITHUANIA

It‘s the most wonderful

time of the year...

Twelve different dishes are served on the table because Jesus had twelve apostles. All the dishes are strictly meatless: fish, herring, slizikai with poppy seed milk, kisielius (cranberry pudding), a dried fruit soup or compote, a salad of winter and dried vegetables, mushrooms, boiled or baked potatoes, sauerkraut (cooked, of course, without meat) and bread. Gero apetito! Skanaus!

Photo from: http://www.thebluegrassspecial.com

Text: Saulene Valskyte

Christmas is probably the most important celebration in the whole Christian world, but Lithuanian Christmas traditions are outstanding, even in this context. Lithuania has a very rich history and the many historical events have influenced our traditions – starting with hints of paganism, followed up by remains from the Soviet occupation, and finishing up with an intervention of the modern world. In this article I will tell you a little bit about our Christmas traditions – how they should be and what are still very much are also today. Gero apetito! Skanaus! Linksmu Kalėdų!

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - (1) Comment

CHRISTMAS IN LITHUANIA

It‘s the most wonderful

time of the year...

Twelve different dishes are served on the table because Jesus had twelve apostles. All the dishes are strictly meatless: fish, herring, slizikai with poppy seed milk, kisielius (cranberry pudding), a dried fruit soup or compote, a salad of winter and dried vegetables, mushrooms, boiled or baked potatoes, sauerkraut (cooked, of course, without meat) and bread. Gero apetito! Skanaus!

Photo from: http://www.thebluegrassspecial.com

Text: Saulene Valskyte

Christmas is probably the most important celebration in the whole Christian world, but Lithuanian Christmas traditions are outstanding, even in this context. Lithuania has a very rich history and the many historical events have influenced our traditions – starting with hints of paganism, followed up by remains from the Soviet occupation, and finishing up with an intervention of the modern world. In this article I will tell you a little bit about our Christmas traditions – how they should be and what are still very much are also today. Gero apetito! Skanaus! Linksmu Kalėdų!

First of all I have to point out that in Lithuania Christmas Eve (Kūčios) supper is the most important part, normally celebrated at home with family and close relatives. Also lonely people are invited to the Christmas eve supper, because nobody should be alone at Christmas. Another important thing to say is that during Soviet occupation not everyone celebrated Christmas. For example my mother didn't celebrate as a child, because my grandma was afraid that if children said something at school they might get in to trouble and since my grandma, being a doctor, was already watched by authorities (everyone could be tracked by the authorities for all kinds of reasons, especially medical staff as they were working with what was considered criminals against the nation, and had possibilities to help them) she didn't want to risk.

Preparation for Christmas starts at the beginning of Advent. According to the folk calendar Advent is the peace, spiritual purification time, in this time farm work is completed. Advent begins with St. Andrew's day, lasts four weeks and ends on Christmas Eve. Advent means not only peace, but also a mysterious, mystical time, when the spirits of the spirit-world is trying to interfere in people's lives. The elders believed that this dark time the spirits are creeping around, trying to cause harm to people and their jobs, winter crops, livestock etc. Therefore, various prohibitions were abundant. That included household works, nutrition and entertainment. There were certain works forbidden at this time: deforestation, sheep shearing and other noisy activities. It was forbidden to dance, sing and party, also to stay up late in the evenings. People couldn't eat meat and fat food (with an exception for children and sick people). From all that there are only a few things left these days – some of people don't party as much and there are some that don't eat meat, but not during all Advent, usually just the last week before Christmas. One more tradition is to make Advent wreaths – a wreath with four candles (one candle per Advent week), it usually stands in the window and every week there is one more candle burning.

At the day of Christmas Eve all noisy works were strictly forbidden, because that would bring thunderstorms the upcoming summer. People washed themselves according to rituals. Then they were preparing the table for the supper. In Lithuania Christmas eve day is a national celebration, so no one has to work (shouldn't work, but all supermarkets and shops are usually open, just close a bit earlier).

Preparing a Christmas Eve table was very important. Now not so many people do it by the rules, but the right kind of preparation makes the Christmas Eve supper more special and fun. First of all there should be some straw put under the white tablecloth (after supper straws are used for some magic when each person draw a straw without looking, the length of a straw symbolizes length of the person’s life).

There is always one empty place at the table, for the spirits of dead relatives. Also, some food must be left in that plate for the following night. The Christmas Eve table is decorated with candles, that also are used for some magic after the supper. Pouring wax is another Christmas Eve ritual, the rules are: take a candle from table (the ones that were burning all night long) and pour the wax from them in to the water bowl without moving your hand around (the hand has to remain steady while pouring the wax). After the wax has become hard take it from the bowl and turn it, and you will see a strangely shaped figure. Hand that figure over to the oldest member of the family, who then will explain for you what he/she sees in it and what is waiting for you in the future.

The Christmas Eve supper should be eaten when the evening star rises, always including twelve dishes. Everyone has to try each dish.

Plotkelė – Christmas wafers.

Breaking plotkelė.

There is also a special white pastry that people can get in the church. Lithuanians call it "plotkelė" (Christmas wafer). There should be one for each member of the family. In the very beginning of the Kūčios supper starts everybody prays and then breaks plotkelė and tell what they wish for each others. The lotkelė is also known as kalėdaitis, paplotėlis, plokštainėlis or Dievo pyragai depending on the region of Lithuania a family is from.

Meat is forbidden until Christmas Day morning, the meatless supper is probably the one tradition that everyone in Lithuania still follows.

Some Christmas Eve games to play after the supper:

Draw Kūčiukai

This is game for single girls. Put your hand in to the bowl of Kučiukai and grab as many as you can, then put them on the table. If the number is even you will find a guy, if not you will remain single the coming year.

Kūčiukai

Pick up firewoods

It's very similar to Draw Kūčiukai. Go to the place where you are keeping the fire wood and take as many logs as you can. Than count them, if the number is even you won't be single next year if not you will remain single.

Glass of water

Before going to sleep eat as much herring or just fish as you can, and put a glass of water next to your bed. In your dream, a guy will hand you that water and he will became yours husband one day.

Throw a shoe

This is a game for those who still lives with their parents. Stand in the room so that your back would be facing the door and throw a shoe over your head or shoulder. Then look which way shoe has landed. If the shoe is facing the doors this year you will be leaving home, if it's facing into the room you will stay at your parents.

As I mentioned earlier, the Christmas Eve supper includes twelve dishes. There are some dishes that are "musts" and some optional. "Must" dishes on Christmas Eve table are Kūčiukai (It's very simple Christmas eve pastry with poppy seeds, it's not very sweet, but very delicious. It's made by mixing 0.5 kg of flour, a bit less than 200 ml of milk (water), 50 grams of oil, a pinch of salt, 20-30 g of yeast, a quarter cup of poppy,100 grams of sugar. Raise a dough a bit and form little kūčiukai, then bake it).

Another very traditional dish is cranberry pap. Pap can be served as a dessert or a drink, depending on the consistency of the pap (it's a berry drink or dessert made from water, berry juice, sugar and starch).

Because meat is strictly forbidden there are a lot of fish dishes on the table. Most popular are herring dishes. Herring with carrots, or red beets, are most common. Also all kinds of mushrooms are used for Christmas food.

Typical herring dish.

Now for a lot of people Christmas is associated with mandarins. This came from the times of Soviet occupation. There were mandarins appearing in shops all around Lithuania during Christmas time, so people were spending hours standing in huge lines outside the groceries, to get some fresh fruits in the middle of the winter. Of course because of communistic regime there were set certain amounts per person to buy, so fruits in wintertime were especially valued. Even now, and even for the younger generatio,n the smell of mandarins reminds us about Christmas.

Christmas is the time to celebrate and spend magical time with our families, and although we live in the modern world and have less and less time for ourselves, let’s stop for a minute, for Christmas, for ourselves, for our families and let’s make this celebration special, remembering our heritage, who we really are and what makes us special. Have a merry and very Lithuanian Christmas!

Linksmu Kalėdų from Saulene!

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - (0) Comment

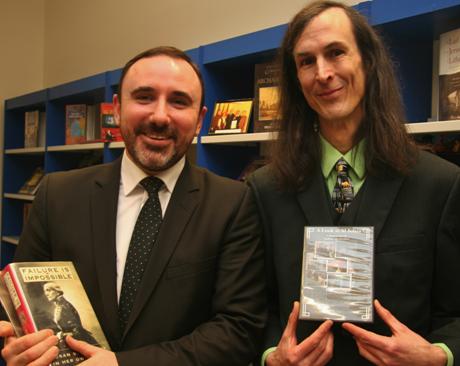

OPENED TODAY, FRIDAY 16 DECEMBER 2011

First Jewish library in

Lithuania since WWII

“Failure is impossible,” is the title of the book that was held by Lithuania’s Minister of Culture, Arūnas Gelūnas (left), at the opening of the Vilnius Jewish Public Library Friday 16 December. Wyman Brent, the Californian book collector behind the amazing collection of more than 5.000 books, plus videos and CDs, says today is one of the happiest days in his life.

Photos: Aage Myhre.

Friday 16 December 2011 the new Vilnius Jewish Public Library, located at Gedimino Avenue 24, 2nd floor, in Vilnius was officially opened. Guests from USA, Israel, European Parliament, Seimas (Lithuania’s parliament) of the Republic of Lithuania, Government of the Republic of Lithuania, Lithuanian Ministry of Culture, Lithuanian Ministry of Foreign Affairs and others were participating.

On Saturday 17 December 2011, from 11:00 to 17:00 the library will be open to the general public, giving everyone an opportunity to view the premises, the collection of books and photographs, the exhibits, and a presentation of a slide-show giving a retrospective of the establishment of the library. Visitors will be greeted and will have the opportunity to speak with the initiators of the library.

Panel at the press conference (l/r): Davia Kiminaite, Wyman Brent,

Miša Jakobas, Petras Zurlys, Arūnas Gelūnas and Petras Austrevičius.

Daiva Kiminaite is now Head of the Vilnius Jewish Public Library |

The composer Anatolijus Šenderovas with Wyman Brent. |

Žilvinas Beliauskas (left) and Petras Zurlys have both done a great job

for the realization of the library.

Read also:

The California Baptist who collected 5000 Jewish books and brought them all to Lithuania

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - (10) Comment

OPENED TODAY, FRIDAY 16 DECEMBER 2011

First Jewish library in Lithuania

since WWII

“Failure is impossible,” is the title of the book that was held by Lithuania’s Minister of Culture, Arūnas Gelūnas (left), at the opening of the Vilnius Jewish Public Library Friday 16 December. Wyman Brent, the Californian book collector behind the amazing collection of more than 5.000 books, plus videos and CDs, says today is one of the happiest days in his life.

Photo: Aage Myhre.

Friday 16 December 2011 the new Vilnius Jewish Public Library, located at Gedimino Avenue 24, 2nd floor, in Vilnius was officially opened. Guests from USA, Israel, European Parliament, Seimas (Lithuania’s parliament) of the Republic of Lithuania, Government of the Republic of Lithuania, Lithuanian Ministry of Culture, Lithuanian Ministry of Foreign Affairs and others were participating.

On Saturday 17 December 2011, from 11:00 to 17:00 the library will be open to the general public, giving everyone an opportunity to view the premises, the collection of books and photographs, the exhibits, and a presentation of a slide-show giving a retrospective of the establishment of the library. Visitors will be greeted and will have the opportunity to speak with the initiators of the library.

The impetus for the library was from a private collector, humanitarian, and visitor from the USA -- Mr. Wyman Brent. His initiative was to bring to Vilnius, and thereby to pass to Lithuania, a collection containing more than 5,000 valuable books. The collection consists of books by Jewish authors, as well as books on Judaism by non-Jewish authors.

Wyman Brent first came to Vilnius in 1994, telling that he fell in love with Vilnius already by then. Over the course of several years, he become interested in Jewish culture, history, and heritage, and came to follow the path towards his dream -- to establish a Jewish Library in Vilnius.

Wyman Brent is convinced that as soon as the library officially opens its doors, then the love of Litvaks (i.e., Lithuanian Jews) and their longing for their old motherland of Lithuania will encourage a continuous flow of literary, artistic, and informational valuables to The Northern Jerusalem, as Vilnius was once called. Moreover, the library will urge many peoples to visit Lithuania in attempts to rebuild devastated human and cultural treasures, and to re-establish internal and international bridges.

Activities of the Vilnius Jewish Public Library will encourage visitors to revive the traditions of Jewish book culture and community libraries, offering a public space to encourage knowledge of the capital’s cultural diversity and history, and will become a cultural center with a variety of continuing exhibitions, events, meetings, and concerts.

Vilnius Jewish Public Library is founded as a structural sub-division of the Vilnius County Adomas Mickevicius Public Library.

Panel at the press conference (l/r): Head of the library Davia Kiminaite, book collector Wyman Brent,

Rector of the Vilnius Jewish School Miša Jakobas, Director of the Lithuanian Librarians’ Association Petras Zurlys,

Minister of Cultre Arūnas Gelūnas and Member of Parliament Petras Austrevičius.

Daiva Kiminaite is now Head of the Vilnius Jewish Public Library.

If questions or requests, please write Daiva at

daiva.kiminaite@amb.lt

Žilvinas Beliauskas and Director of the Lithuanian Librarians’ Association, Petras Zurlys, have both done a great job

for the realization of the library.

This couple has played a major role in supporting and contributing to the library from their Helsinki location,

Inna Rogatchi and Michael Rogatchi of the ‘Inna & Michael Rogatchi Foundation’.

Rector of the Vilnius Jewish School Miša Jakobas with Wyman Brent.

Composer Anatolijus Šenderovas with Wyman Brent.

Lithuania’s Minister of Culture, Arūnas Gelūnas interviewed by Lithuanian Radio’s correspondent Olga Ugriumova.

Tenor Mindaugas Zimkus with Wyman Brent.

Also Lithuania’s Prime Minister, Andrius Kubilius (centre), came to participate in the opening ceremony.

Photo: William Adan Pahl (Billy Pahl)

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - (0) Comment

A LETTER FROM MASHA KAMENETSKAYA, ONE OF MANY

PROTESTERS IN ST. PETERSBURG, RUSSIA, LAST SATURDAY

When you feel that you have done the right thing in the right place

This is a letter from Masha Kamenetskaya, a young journalist and writer from St. Petersburg, Russia. She is describing her participation in the evening after the 10 December protest for fair elections in the city on the Neva.

SATURDAY 10 DECEMBER 2011: Finally I am home -- after a good and such a... real day. Even a romantic one, in some sense, when you feel that you have done the right thing in the right place.

I spent the day with my friends and loved ones -- who would have thought that a meeting of protest can be such a great occasion to see friends and to catch up with them? And I spent the day with the people living in the same city as I do. The people who smiled and who cared.