THE VOICE OF INTERNATIONAL LITHUANIA

|

VilNews has its own Google archive! Type a word in the above search box to find any article.

You can also follow us on Facebook. We have two different pages. Click to open and join.

|

Historical Lithuania

- Posted by - (2) Comment

|

Commemorating January 1991

|

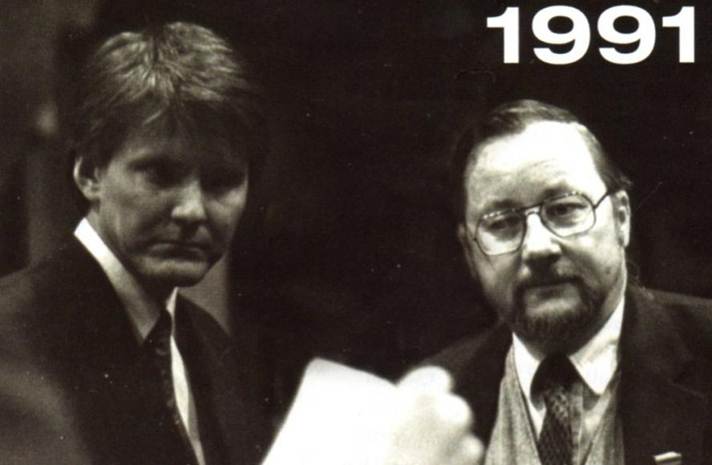

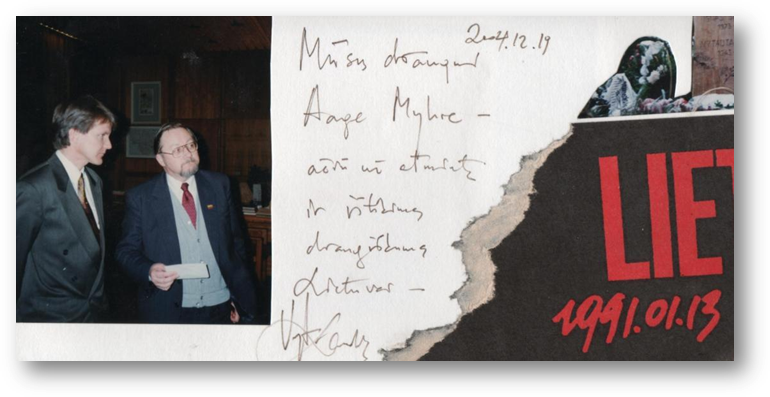

21 January 1991: Soviet military vehicles dominated the streets of Vilnius. Dag Andersen and I presented a letter from Oslo Municipality, signed by Mayor Michael Tetzschner. Oslo offered Vilnius to become its first friendship city in the West. The letter was enthusiastically received by the Vilnius Mayor Arunas Grumadas and Deputy Mayor

Regimantas Ciupaila. Photo: Aftenposten, Norway.

Aage Myhre, VilNews Editor-in-Chief

aage.myhre@VilNews.com

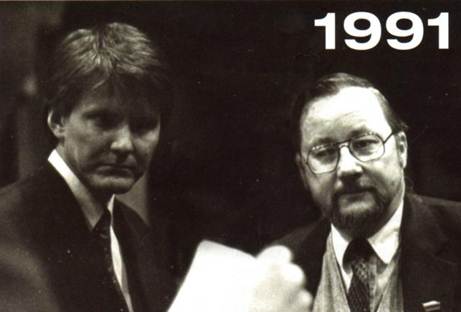

We were two Norwegians working very much with Lithuanian affairs during autumn/winter of 1990-91, Dag Andersen and me. During our visit to Vilnius in January 1991, we showed our respect to President Vytautas Landsbergis in his Parliament office and worked with journalists to spread the message about the Soviet assault to the world.

We also brought with us a letter from the City Council Leader of Oslo, Michael Tetzschner inviting the Mayor of Vilnius to sign a sister city agreement. We handed the letter over to Mayor Arunas Grumadas on 21 January while Soviet troops were standing around in the streets and armoured vehicles roared around us.

The twin city agreement was signed a few months later, and Oslo became thus the first Western city to enter into such an agreement with Vilnius. I saw it as an important symbol of friendship and solidarity at a difficult time for a country under tremendous pressure and terrible abuse from Lithuania’s power loving neighbour to the east.

|

OSLO

The Oslo coat of arms is almost 700 years old. It shows the patron saint, of Oslo, St. Hallvard, sitting on a throne decorated with two lions' heads with a halo around his head. In front of the throne lies the woman whom he tried to protect. In one hand he holds the three arrows which killed both him and the woman. |

VILNIUS

In pagan times, until the end of the 14th century, the Vilnius coat of arms featured Titan Alkis, hero of Lithuanian ancient tales, carrying his wife Janteryte on his shoulders across the river.

|

During 1991 I came back to Lithuania several times. I saw more, understood more. The country began in earnest to fascinate me. I was also in Vilnius during the failed coup in Moscow in August 1991, again thrilling days. On the morning of 30 August 1991 I was probably the first person in modern times who got a Lithuanian visa that was legally accepted internationally, stamped into my Norwegian passport. Early morning the 30th of August 1991, the day when the Lithuanian migration authorities finally could do so in accordance with international rules.

The Soviet Union was finally a horror of the past. Also formally, Lithuania was once again a free and independent country. 50 years of abuse and oppression was over!

Vilnius images, winter 1990-91

|

|

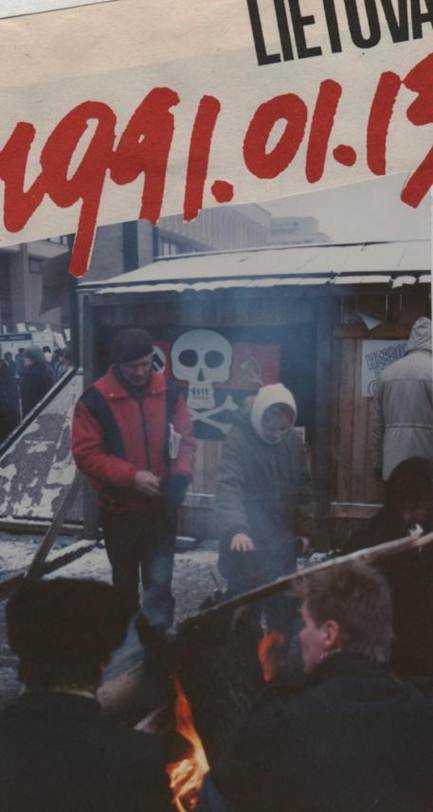

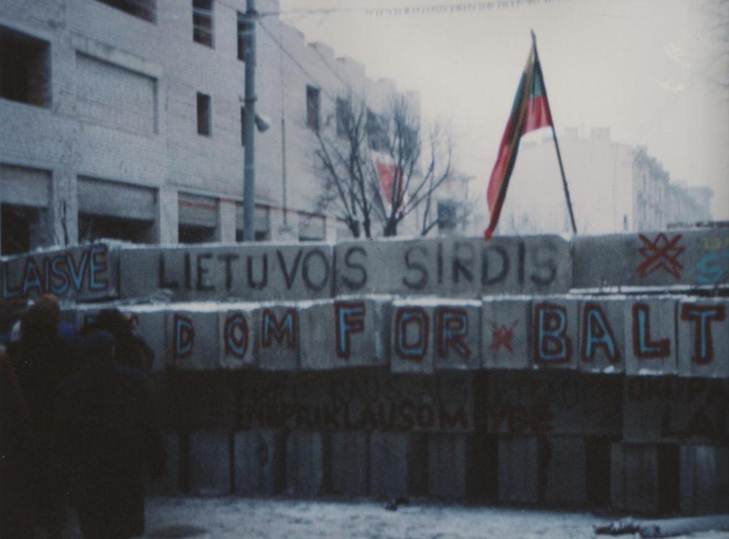

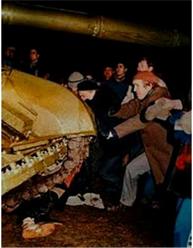

Heavy tanks were used by the Soviet forces when they attacked the TV tower and the Parliament building in Vilnius on 13 January 1991 (left). They were met by a wall of unarmed people who refused to allow the intruders to again take control of their homeland. Inside the city they used armoured vehicles on rubber wheels (below). It was a bizarre, almost surreal experience to always hear the noise, feel the ground tremble when we were in meetings or trying to get a meal in one of the city's few restaurants. |

|

|

|

We often did our eating and drinking in Hotel Lietuva, in the so-called 'Black Bar', where only western, hard currencies were accepted. This bar was the centre for international media those January days. Every night we heard stories about how television crews and journalists had experienced rather harsh confrontations with the Soviet military units. |

|

||

Windows all over Vilnius were taped like this those

January days, in order not to break when the heavy

Soviet vehicles passed by.

|

|

|

|

|

ABOVE: During my first visit to Lithuania, in November 1990, I took this picture at Rotušes Square (Town Hall Square) in Vilnius. This was probably the very last picture ever made of the statue of Vincas Mickevičius-Kapsukas here. Next morning he had been knocked down by local activists... After the WWII Soviet occupation of Lithuania, his student Antanas Sniečkus (see our article https://vilnews.com/?p=6598) propagated Mickevičius' personality cult. In his honour the city of Marijampolė was renamed Kapsukas (1956–1989) and Vilnius University (1955–1990) bore his name. Two large sculptures of Mickevičius were erected in Vilnius: one here, in front of the Vilnius Town Hall (1962) and another, depicting Mickevičius with Lenin, in Antakalnis (1979). LEFT: You can today find the statue of Mickevičius-Kapsukas in the Grutas Park in Southern Lithuania. The park is the repository of old Soviet era statues and artefacts that were removed from public places when Soviet occupation of Lithuania ended.

|

Delivery of coal to properties in Pilies g. right in the centre of Vilnius, with horses, 22 years ago.

People picked the coal up in burlap sacks. Other times the horse driver was simply shovelling

the coal out on the sidewalk in front of the buildings on his ordering list.

Photo: Aage Myhre.

One of the few shop windows in Vilnius in 1990-91.

Photo: Aage Myhre.

We came via Riga

We were a small group of Norwegians who travelled from Oslo to Vilnius a few days after the infamous Soviet attack and its killings on the 13th of January 1991. It was originally planned as a larger delegation, with parliamentarians, but they had to postpone their trip due to the death of our Norwegian King Olav.

We came to Vilnius via Copenhagen and Riga, whereto Scandinavian Airlines as the first western airline had established a route a few months earlier. Travel insurance cover was 400% higher than normal. The Baltic States were now defined as a war zone.

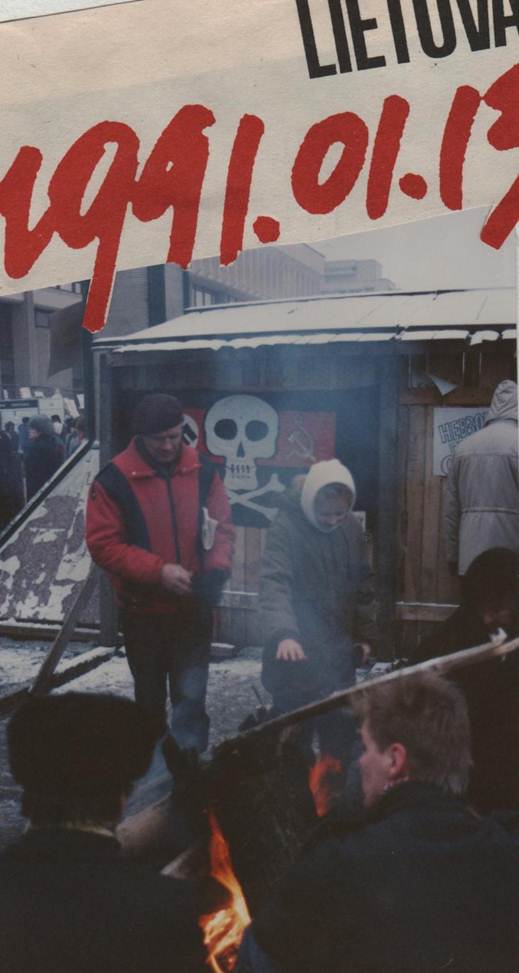

In Riga we first visited the Radio and Television House. The smoke from the many bonfires around the building lay like a blanket over the area, with a penetrating but good smell of firewood. It was an impressive sight to see the thousands of Latvians who camped around the territory in tents and primitive shelters to protect the freedom of peaceful broadcast against the Soviet perpetrators.

Inside Riga's Old Town there were equally many bonfires and barricades, especially around the Latvian parliament building. Our delegation was given entrance passes, and that night we stood inside the building to show our support and talking to MPs and others who stayed there, many of them around the clock.

In the evening we experienced a rather startling example of the Soviet propaganda machinery when there on the TV news from Moscow was informed that Soviet soldiers had just moved in and taken control of the Parliament and Riga city. Not a single soldier was to see, neither inside nor outside the building, but this was a stunning reminder of how disinformation and propaganda are important parts of any war or conflict.

It was dangerous to embark on the road those days, but the Latvian Customs agreed to drive us, in their red jeeps, to the Lithuanian border next morning. On the Lithuanian side of the border, which still was not established with checkpoints, we were picked up by Lithuanian Lada cars, and not long after we were on the way to Vilnius. We passed convoys of Soviet military vehicles, but arrived without being stopped or subjected to interrogation of any kind.

Our main mission of the trip began…

We, our Norwegian team, together with journalists travelled to Latvia and Lithuania as soon as we could after the Soviet attack in January 1991. The Balts refused to accept the Soviet invasion. They did their utmost to protect their governments and media. Here we are with 'activists' in Riga. For several weeks they made bonfires, staying here in tents night after night to demonstrate against the new Soviet assault.

Photo: Aage Myhre, January 1991.

Without the intense media coverage that took place in January 1991, the outcome could well have become different. The Soviet occupiers could have re-taken control of the Baltic States. Here a journalist from Norwegian Aftenposten interviewing the leader of the Latvian border guards. The international press made a huge effort to make the world know about the Soviet atrocities.

Photo: Aage Myhre, January 1991.

Lithuania – Norway, a strong alliance also today!

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - (1) Comment

Visit to the Lithuanian

Parliament (Seimas)

22 years later

Lithuanian Foreign Ministry issued primitive passes for us,

and we managed to get through a long maze of controls,

barbed wire, concrete blocks and barricades that surrounded

the Lithuanian Parliament those January days in 1991. We got

the opportunity to visit this brave Parliament President,

Professor Vytautas Landsbergis, in his office. Here he

lived day and night for weeks while the Soviets

surrounded the building with troops and tanks.

Text and photos: Aage Myhre, Editor-in-Chief

aage.myhre@VilNews.com

This year I marked 13 January in the Lithuanian Parliament Building, 22 years after I in 1991 stood here in this building, along with Professor Landsbergis and looked out the window at the bonfires, barricades and the huge crowd of unarmed people who had gathered to protect their president and the country's future as a free nation.

I came here today with a group of young Lithuanians, most of them so young that they do not have their own memories of what happened here 22 years ago. Yet the memories of the sad events in January 1991 are very much alive and present for them. They want to remember that freedom and independence is not something you can take for granted, and they want to pursue a political career. They are Lithuania's future politicians. They are the future of young, well-educated, smart leaders that this country a few years ago could only dream about.

I walked around with them in the Parliament this 13th January. I saw their interests, and their pride in belonging to a great nation like this.

I also saw large photographs on the walls, with Lithuania's parliamentary history of the interwar time and from the years after the Declaration of Independence 11 March 1990. The sadness I felt when I walked around in these corridors 22 years was gone, now I felt only joy, and optimism regarding the country's future and its political leaders for the years to soon come.

Entrance to the old part of the Parliament.

HISTORY OF TODAY’S PARLIAMENT BUILDING (SEIMAS)

The construction of the new Seimas building began in April 1976, on the site of a former stadium. By then, the Parliament was still directly depended on the Communist Party. The legal acts passed by the Supreme Council of the USSR was just a “decoration” of the Soviet order. Selected by sex, nationality, education, professions, membership in Communist or Young Communist organisations, the local trade union, so-called deputies used to convene two or three times per year and voted on the draft legal acts already submitted. Undoubtedly, this was an imitation of government, a spectacle. Indeed, the main lobby could remind one of a theatre.

Today’s democratic parliamentarian system got its first test on 11 March 1990, when the Lithuanian Supreme Soviet elected Vytautas Landsbergis president and formally declared Lithuania to be an independent nation. The Soviet President M. Gorbachev rejected the action, insisting that a separation had to be negotiated. In April same year he ordered an economic blockade of Lithuania, cutting off all oil supplies and reducing natural gas flow to one-quarter of the normal level. The blockade ended on 30 June after the Lithuanian Parliament voted to freeze the declaration of independence for 100 days in order to permit negotiations between Moscow and Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania.

Then came 13 January 1991. That was the day when Soviet troops cracked down in Vilnius and the resulting bloodshed made headlines around the world. The action was apparently a bid to stop Lithuania’s independence drive in its tracks. But President Landsbergis and other political leaders wanted it all very differently, making the Parliament building a fortress for democracy and freedom those winter days, with thousands and thousands of unarmed Lithuanians surrounding the building and thereby stopping the Soviet troops from attacking.

ABOVE: The Lithuanian Parliament building as it looks today.

BELOW: Pictures on the Parliament walls, describing Lithuania’s parliamentarian events in 1990-1991.

ABOVE: Seimas, 11 March 1990, the day Lithuania re-claimed its independence.

BELOW: The same Parliament Hall today.

Today’s top modern Parliament Hall.

|

|

On the 11th of March 1990 the Lithuanian Supreme Council (today’s Parliament) decided to change the Soviet Coat of Arms hanging behind the chair of the parliament president (above), to Vytis, the symbol of genuine Lithuania (left). The coat of arms of Lithuania, consists of an armour-clad knight on horseback holding an olden sword and shield, also known as Vytis ("the Chaser"). The Lithuanian coat of arms is one of the oldest national coats of arms in Europe. It is one of very few containing symbolism adopted from ducal portrait seals rather than from coats of arms of dynasties, which is the case for most European countries.

|

ABOVE: Barricades and bonfires outside the Parliament in January 1991.

BELOW: This is what is left of the barricades today, covered by a modern glass structure.

BELOW: The Parliament’s entrance hall on 13 January 2013, filled with activities in memory of 13 January 1991.

80 year old Liuda Komarovskaja lost her health by defending the Vilnius TV Tower in the 13 January 1991 events.

She was beaten unconscious by the Soviet soldiers and rushed to the Santariškių Hospital in the outskirts of Vilnius. Here in conversation with Parliamentarian Petras Austrevicius in the Parliament last Sunday.

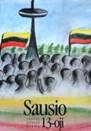

ABOVE: Antanas Terleckas, founder and leader of the Lithuanian Freedom League, was awarded the 2012 Freedom Prize at a solemn event at the Lithuanian Parliament on Sunday 13 January. Read more at http://www.15min.lt/en/article/culture-society/freedom-prize-awarded-to-lithuanian-freedom-league-leader-antanas-terleckas-528-296400

BELOW: A special exhibition about Antanas Terleckas’ life was presented in the Parliament during the13 January commemoration days.

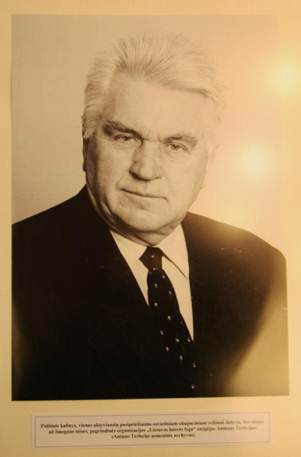

BELOW: Pictures on the Parliament walls, from interwar sessions.

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - (0) Comment

The bonfires and

The bonfires and barricades that

saved Lithuania

In

January 1991, the Lithuanian Parliament was for weeks surrounded by hordes of people,

bonfires, concrete blocks and vehicles that the Lithuanian people had brought

there to protect their leader and their elected representatives against the

Soviet atrocities against innocent people. Today, exactly 22 years later,

the

Parliament is surrounded by peaceful, quiet winter streets.

Top

photo: Zenono Nekrošiaus

Text

and photos: Aage Myhre, Editor-in-Chief

aage.myhre@VilNews.com

It was not bonfires, concrete blocks, steel beams, barbed wire or tractors which in themselves rescued Lithuania in January 1991. But it was these simple remedies, not weapons, that came to represent the peaceful resistance Lithuanians showed towards their powerful opponent from the east.

I'll never forget the sight of the flames and the large crowd that met me the day I was walking down the Gedimino prospekto towards the Parliament an icy winter day in January 1991. I read a combination of hope and despair in the faces, but first of all I saw determination. This time we will not surrender! The Soviet Union shall not again be allowed to trample us down under its iron heel!

The tactics succeeded. The Lithuanian people united as never before, or since, and the assailants had to withdraw in favour of a free and democratic Lithuania. Some of the symbols of this defining moment in our country's history can still be seen outside the Parliament.

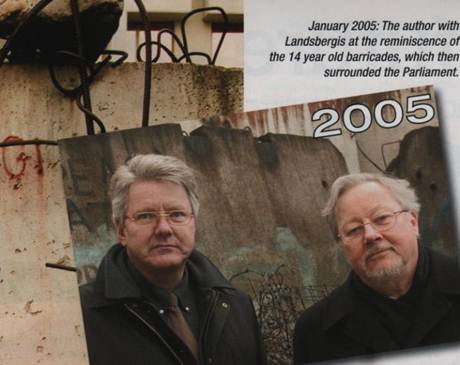

In

January 1991 I crossed the barricades to visit President Vytautas Landsbergis

in

his Lithuanian Parliament office, while the Soviet troops and tanks continued

to

surround the building. 14 years later we visited together what was left of the

concrete

barricades from that time. These are now protected by a glass structure.

1991

2013

1991

2013

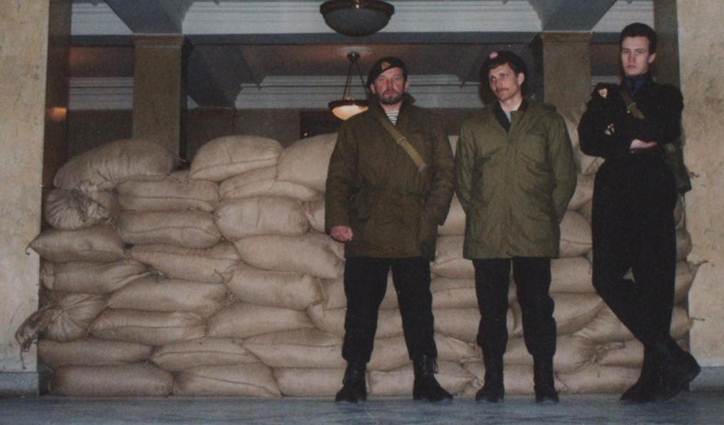

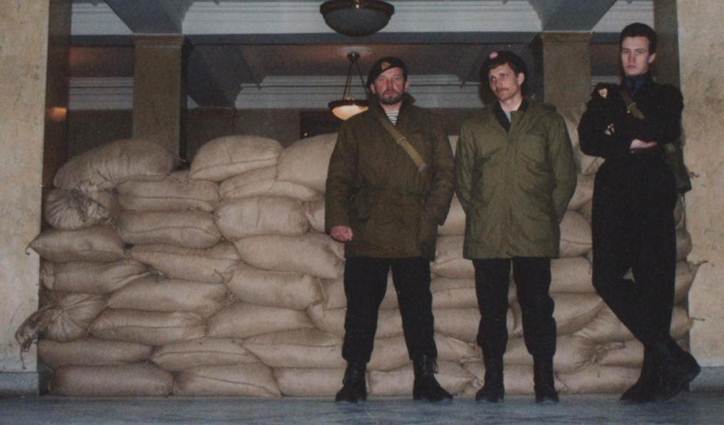

It

was very touching to see how the Balts acted to keep their newfound freedom and

protect their home country during the very difficult January days of 1991. Here, at the entrance to the Lithuanian Foreign Ministry,

the young men have put on homemade clothes that are meant to look like

uniforms. They carry rifles and other

weapons they have found in their homes. Sand

bags have an important symbolic effect. Brave guys!

Photo:

Aage Myhre, 18 January 1991.

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - (0) Comment

How a Lithuanian from America

ended up in the middle of historic

Jan. 13 events in Vilnius

By: Linas Johansonas LTnews.net

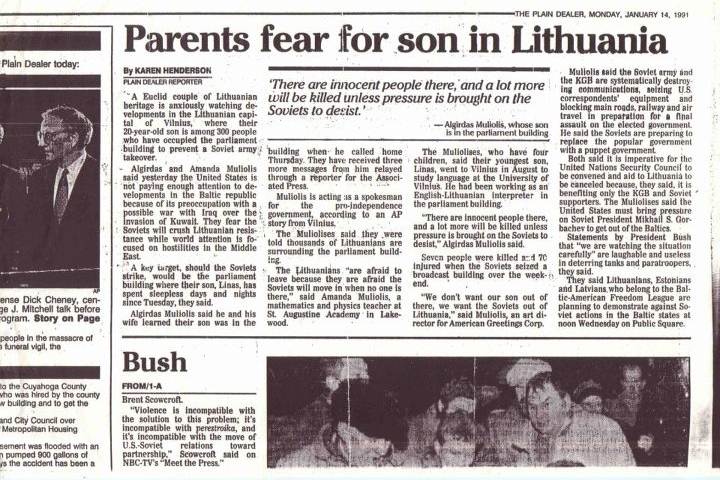

(Cleveland) Linas Muliolis was your average young Lithuanian born in the USA. The son of World War II refugees, Linas grew up in Cleveland's Lithuanian community. In January 1991, he was just a month away from turning 21 years old & was in Vilnius during the historic Jan. 13 events. Earlier this week, LTnews.net talked with Linas about his experiences 22 years ago.

HOW DID A YOUNG MAN FROM CLEVELAND END UP IN VILNIUS DURING A 'REVOLUTION'? "I went there (Lithuania) to live for a year, to study language at Vilnius University. Things were heating up and in the beginning of January, I went there (parliament building) and volunteered to be an interpreter. I worked in the information bureau with Rita Dapkute".

WERE YOU AT THE PARLIAMENT BUILDING ON JAN. 13? "Yes. I was there for four days with only two, four-hour breaks of sleep ..... Had my own gasmask issued to me". (it was 108 hours with 2 four-hour naps)

WERE THERE ANY OTHER "VOLUNTEERS" FROM ABROAD THERE? "From America, I think Rita Dapkute, Darius Suziedelis & I were the only 3. There was a group from Moldova. There was about a half dozen of them, in case of attack, they were there mostly for moral support but it was nice to have them there... very well received".

SO THE MOLDOVANS WERE THERE TO DEFEND THE PARLIAMENT BUILDING? "Basically yes... I can't remember if they were armed... I think I only remember seeing guns once ..... on the main floor..."

DID YOU EVER WORRY ABOUT WHAT WOULD HAPPEN TO YOU IF THE SOVIETS TRIED TO OR DID TAKE OVER THE PARLIAMENT BUILDING? "No, not at all, why would I worry about that? (he answered jokingly). I made sure I kept my passport with me at all times, in case.. who knows if it would have helped, though. I always said the rest of my life would be anti-climactic".

WERE YOU EVER TOLD WHAT TO DO IF THE BUILDING WAS ATTACKED? WERE YOU GIVEN A GUN? "No - there were practically no guns to be seen, this was primarily a peaceful protest... I WAS issued a gasmask though, because there were rumours of attack by gas".

WAS THERE EVER A TIME YOU THOUGHT TO YOURSELF 'WHAT AM I DOING HERE? AM I GOING TO DIE'? Yes, the whole time!

WHAT WAS THE MOOD LIKE INSIDE THE PARLIAMENT BUILDING ON JAN. 13? "STRESS! Pretty much what you would expect, desperation, frustration with the rest of the world, stress, worry, fear... etc".

WHAT WAS THE FRUSTATION WITH THE REST OF THE WORLD?

About non action. I remember one newspaper cartoon, for example, a rear view of Landsbergis facing a window, you see from the back that he is holding a phone, the view out the window shows a new oil well spraying oil in the air.. He says "President Bush? Guess what!"

The world was focused on the first Iraqi war, but yet on Jan 13th, we still made the top headline

DID YOU EVER CROSS PATHS WITH VYTAUTAS LANDSBERGIS DURING THIS TIME? "Yes. I was in his office once or twice, I was called in to help translate one night.. but I didn't do a great job, though, I have to admit. Once you get technical in some subject, you know how hard it can get".

WHAT WAS LANDSBERGIS LIKE? "He was calm, focused, definitely calm and reserved".

WHEN DID THOSE OF YOU IN THE PARLIAMENT BUILDING HEAR ABOUT THE CIVILIAN DEATHS? We heard about the deaths as they were happening. I remember the death count rising. I was surprised how accurate the news reports were in the US and in the UK, everything was pretty accurate, sometimes the number of deaths was off, but considering how confusing the time was overall, the news articles I saw were close to reality.

DID YOU HAVE ANY CONTACT WITH YOUR FAMILY BACK IN CLEVELAND? Yes. After I took the photo of the Soviet tanks (posted below) I was on the phone with my mother at the time, "Mom, don't be scared, but there is a column of tanks going by" probably was not a good thing to say to my mom. She turned gray that year.

BEING AN AMERICAN-BORN LITHUANIAN, HOW WERE YOU TREATED BY THE NATIVE LITHUANIANS IN THE PARLIAMENT BUILDING? "People were grateful for me being there. I was generally well accepted By that time I had learned to look and act local, gotten rid of most of my American accent, though"

WAS THERE ANY SINGLE MOMENT THAT STANDS OUT FOR YOU? "The single most amazing thing I saw happened late at night, I believe it was on the night of January 12th, I may be wrong. Do you remember the photo of the lone Chinese man standing in front of a column of tanks at Tiananmen Square? The Parliament Building is right next to the river, and there was a bridge over it leading to the square where hundreds of thousands of people were protesting and guarding our fledgling government. That night, suddenly someone in the room called out, said there were reports of a column of tanks racing towards us.. Hearts pounding, we raced to the windows. I was on the fourth floor so had a great view. A long column of tanks came racing towards us. The most amazing thing I have ever seen in my entire life, was the mass of people simply rush in to block the way. Those tanks would EASILY have crushed hundreds of people in seconds if the continued through. I have never witnessed such bravery and selflessness in my entire life. Luckily, however, at the last seconds, those tanks and APC's slowed down and turned right, away from the Parliament Building ".

WHEN DID YOU FEEL EVERYTHING WAS GOING TO BE OK? "When most of the tanks left".

ANY FINAL THOUGHTS? "This was definitely one of the most memorable times of my life, something I will never forget! My whole life I had been taught that someday Lithuania will again be free, that we needed to keep the language and culture alive.. Then, when I was 20, turning 21 - It happened and I was a part of it!"

Cleveland Plain Dealer - Jan. 1991

Photo by Linas Muliolis taken from parliament building - Jan. 1991

Photo by Linas Muliolis taken from parliament buikding - Jan. 1991

Linas Muliolis - Cleveland, Ohio - 2012

Jenifer C. Dillis Simply heart-stopping...

Linas K Muliolis I have to add something to this, I don't know how I forgot.. You caught me during an extremely busy week for this interview and I did not get enough chance to rehash all of the events. The single most amazing thing I saw happened late at night, I bel...See More

Jean-Paul Le Clercq Go Linas Go! The Soviets had no idea what was waiting for them behind Parliament walls!

Sam Salerno I feel shameful that I've never heard of this. Makes me wonder what else is going on in the world today that I don't know about. You're an Awesome man Linus.

Jūra Liaukonytė Thank you LT news for this interesting interview.

Dana Baltutis Yeah...its an event I wont forget. I still have the videos that my close friend Monika, her mum and I smuggled out via the Australian embassy in Moscow a few weeks later.

Rita Kova Murnane I was there in August of 91...

Jurate Grigonis Dana Baltutis from Australia was also there.

Tony Geraci Wow!

Ruta Rusinas Tomas Zizys from Toronto was also there.

Mardell Ward awesome! that was really interesting.

Dana Baltutis We were standing outside the television station when the tanks came and the soldiers started to jump out of the tanks with their guns.. Ill never forget the rumble and confusion. A friend who I was with got shot in the leg. We had to crouch down and run from the gunfire. People were so brave that night and next morning going to the Parliament knowing what had happened the night before.

Mindaugas Petrauskas Another unsung hero.. The majority of Lithuanian people do not know anything about stories like this.

Giedrius Pavardenis Hey guys, you're all awesome

Roberta Zarnauskaite We can only admire the unity and bravery of people at that time!

I wish nation still has it in the blood!!

Peace to all!

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - (6) Comment

If there were those in the West who had not heard of Lithuania before, they almost certainly had by the end of the day 13 January 1991

Heavy tanks were used by the Soviet forces when they attacked the Vilnius TV tower and the Parliament building on 13 January 1991. They were met by a wall of unarmed people who refused to allow the intruders to again take control of their homeland.

Text: Aage Myhre, editor-in-chief

aage.myhre@VilNews.com

"Lithuanians, do not resist, your government has betrayed you. Go home to your families and children."

This was the repeated announcement from the Soviet military vehicles with loudspeakers on the roofs, so-called sound trucks that rolled through the streets of Vilnius in January 1991. But fortunately for Lithuania and the United Europe that we now take more or less for granted, there was a music professor and a complete small nation that wanted it all differently.

Had it not been for this peaceful struggle of recovered freedom against an invasion and occupation, the people of the Baltic States never wanted or agreed to, the map of Europe would most likely have looked quite different today.

If there were those in the West who had not heard of Lithuania before, they almost certainly had by the end of the day 13 January 1991. It was the day that Soviet troops struck in Vilnius. The bloodshed that followed made headlines around the world. The attack was apparently an attempt to stop the Lithuanian independence movement in its very beginning.

When the smoke of the Soviet weapons ceased, more than a dozen people had been killed, hundreds injured. Soviet’s attack, and especially the killings at the TV tower, brought not only fame and sympathy for Lithuania from around the world, it was also a defining moment for the Lithuanians themselves.

The bloodshed meant that a point of no return had been crossed. If there was someone who until now had believed that a peaceful settlement with Moscow was possible, it was now clear to everyone that such a thing was unthinkable.

The 1991 January events took place in Lithuania between January 11 and 13, in the aftermath of the Act of the re-establishment of the State of Lithuania. As a result of Soviet military actions, 14 civilians were killed and more than 1000 injured. The events were centered in Vilnius, along with related actions in the cities of Alytus, Šiauliai, Varėna, and Kaunas.

Professor Vytautas Landsbergis was the central actor in the drama that took place . The colourful, sometimes tempered music professor who was elected Lithuania's president (chairman of the parliament) in March 1990, and from then on become the symbol of the Lithuanian liberation movement. Before the attack in January 1991, his constant talks about breaking free from the Soviet Union, and Lithuania's moral right to do just that, alarmed observers in the West almost as much as in the Kremlin. When the rage was taken completely out of hand in January 1991, Gorbachev seemed as if he did not understand what was happening right in front of him.

Our little Norwegian delegation met with Landsbergis in the parliament on the 19th of January 1991. He lived there, entrenched, protected by his own people. Tens of thousands were ‘camping’ outside the building, inside homemade barricades of concrete blocks and barbed wire. Trucks and tractors were also part of the barricades. In a circle further out stood the Soviet forces, ready to attack when the command word would be given. Fortunately it didn’t happen. The pressure had become strong from all around the world.

We got through the barricades. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs had provided us with appropriate admission papers. It was a moving encounter with a brave man we experienced inside. The little stroke that fell the huge oak. World history was created there and then. In front of our eyes. We were the eye witnesses.

The editor with President Vytautas Landsbergis in the Lithuanian Parliament (Seimas), while the

Soviet troops and tanks continued to surround the building in January 1991.

Bonfires, day and night, outside the Parliament, January 1991.

Photo: Aage Myhre.

Bonfires outside the Parliament, January 1991.

Photo: Aage Myhre.

A human barricade surrounding the Parliament, January 1991.

Photo: Aage Myhre.

With Landsbergis inside the Parliament, 19 January 1991, and his handwritten greeting to the editor.

Homemade barricades of concrete blocks around the Parliament.

Photo: Aage Myhre.

It was very touching to see how the Balts acted to keep their newfound freedom and protect their home country during the very difficult January days of 1991. Here, at the entrance to the Lithuanian Foreign Ministry, the young men have put on homemade clothes that are meant to look like uniforms. They carry rifles and other weapons they have found in their homes. Sand bags have an important symbolic effect. Brave guys!

Photo: Aage Myhre, 18 January 1991.

Inside the city armoured vehicles on rubber wheels were used. It was a bizarre, almost surreal experience to always be spotting, hearing the noise, feel the ground tremble when we were in meetings or trying to get a meal in one of the city's few restaurants.

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - (0) Comment

13 January 1991

through an artist’s eyes

The photo. |

Artist Ruta Brazis-Velasco: This painting was done as an exercise in college of a trauma painting, done in oil with a pallet knife in 5 minutes. I used a Magazine type book that documented the truth.” |

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - (0) Comment

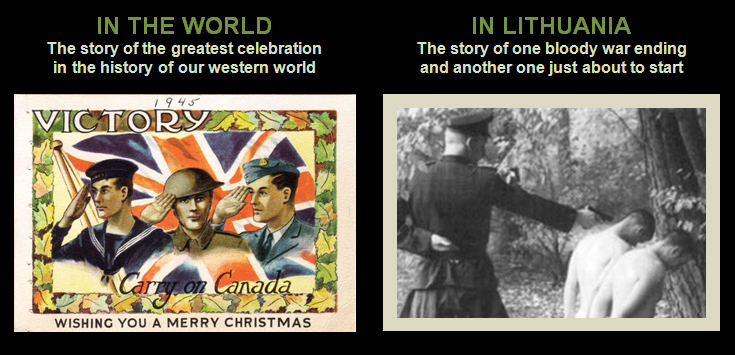

2nd World War was over

- though not in Lithuania

Christmas of 1945 was over most of the world celebrated with a joy and delight almost never before seen. Young and old gathered in homes, on streets and in churches. An endless series of victory ceremonies took place in almost every corner of the world. With a deep sense of joy and gratitude all wanted each other warm, comfortable and relaxing Christmas holidays, knowing that the Nazi era was over and that the world now more than ever could look forward to a future of peace and prosperity. The war had finally released the grip, forgotten was the economic recession of the 1930s. Forgotten was also our Western World’s close friends and neighbours - the Baltic States.

On a small farm in northern Lithuania, in the outskirts of the village Šilagalis, Christmas 1945 is nearing. It is the 22nd of December, and the mother of the house feels very happy that her 21 year old son Povilas has finally come home to visit after having been away for many months.

He has come to change into dry clothes to keep him warm through the cold winter days waiting. His mother is infinitely happy to have her son home this one day, and she does everything she can to treat him with all the good food and drink their little farm can produce. You never know how long it will be till next time.

Povilas had joined a local partisan group earlier in 1945, and now spends all time in the North Lithuanian forests where the local "forest brothers" have established their hideouts. It is from these caches, usually at night, that they conduct their operations against military installations and forces of the Soviet Red Army and NKVD (the secret Soviet police that later changed name to KGB).

The Soviet occupation of Lithuania has lasted for more than a year now, but Povilas and other forest brothers still hope that their constant needle sticks can get Josef Stalin to pull his troops out of Lithuania and the other two Baltic countries.

Povilas is pleased to finally have got a day off, not least is he happy to eat real Christmas food and enjoy some Christmas cheer with the family. A small fly in the ointment is the fact that his father, little sister and little brother are not home.

Both the brother and the sister go to a boarding school in the nearest town, Panevežys, and his father had early in the morning that same day left for the town to bring them home for Christmas. But his mother is here, and when she and he, with arms around each other, go out in the barn to feed the animals, he sings with joy a song he so often has sung in the partisan camp in recent months:

"Dying young is difficult, but not for my country. For my country, Lithuania, I am ready to sacrifice my young life. "

His mother scolds him motherly strictly that he sings: "You know it is not proper to sing now that it's Advent," she says. Lithuania's Roman Catholic Church is strict when it comes to how to behave through the various festive times of the year, and his mother admonishes her son, therefore, while at the same time feeling proud and happy that he makes such an honourable service to the home country.

Back in the farmhouse they suddenly hear that the dog starts to bark. Through the window they see a group of soldiers approaching. The soldiers are still on some distance, so Povilas has time to hide in a small cellar room they have made beneath the living room floor, and the mother has time to cover the cellar hatch as best she can.

The cellar room has also previously been used to hide partisans, and both think this is a safe hiding place until the soldiers have left again.

The mother walks out into the yard to meet the soldiers from the Soviet Red Army. They ask if her son is home, and if he, in case, is alone. Without waiting for an answer, they storm into the house and begin to turn upside down on furniture and fixtures. Then they start shooting down to the floor to see if it can be cavities under the floorboards. It takes some time before they discover the cellar hatch, but as soon as they find and open it, they fire a machinegun volley into the hole. It does not take long before they pull the now perforated and lifeless body of Povilas out of the basement. The whole operation has taken them five hours, but they have found what they sought. One more young Lithuanian life has been lost in the desperate struggle against the overwhelming odds.

The distance from the farm to the road is over 500 meters, so the soldiers find a chain in the barn so they can tow the corpse of Povilas across the fields over to the military vehicle waiting. The mother is forced to follow, and soon they are on their way to the NKVD headquarters in Panevezys, where the body of Povilas is thrown out in the middle of the courtyard. His mother is brought to a prison cell in the basement.

Early next morning, Christmas Eve 1945, the mother is brutally dragged up from the wooden bench she has laid sleepless on during the night. Today, and every subsequent day for two weeks, she is brought up to ever-new interrogations, walking across the courtyard where the mutilated body of her son still is lying.

Christmas and New Year holiday season in 1945 passes with this terrible routine for a mother in tears and sorrow. Early in January, she is released and can finally go home and tell the family what has happened.

In thousands of homes around the world happy families walk around their Christmas trees. They celebrate that Jesus is born and the world's evil is overcome. 1946 is the beginning of the new and bright times for the human kind…

In northern Lithuania the parents of Povilas and other parents finally find out where the bodies of their killed young partisan sons have been dumped. Under the cover of dark nights in early January 1946, they manage to bring the bodies of their children home to secret burials in their hometown cemeteries.

Christmas 1945 is over. Most of the world looks forward to many good years of peace, freedom and economic growth. The Baltic States' ten-year guerrilla war against the occupiers has just begun.

* * *![]()

The story of Povilas is real. It is based on a passage from the book "Lithuania's struggle for freedom" (Lithuanian Partisans' War Chronicles).

Povilas Peleckas was born on 24 January 1924 into a farming family in the village of Šilagalis in the Panevežys district north in Lithuania. He attended Šilagalis primary school. Later he helped his parents on the farm. In 1944 when the USSR invaded and occupied Lithuania for the second time (first time was in 1940), Povilas was due for conscription into the Red Army. He refused to go. When a local partisan unit was formed, led by Major Januškevičius, Povilas joined the fighters. In September 1945 many of the members of the unit were killed in battle, and another three were killed at the beginning of December. Those who remained alive determined to join a larger partisan unit. But fate was against them.

|

“Across America, people crowd churches praying with gratitude for the peace in place, and reach out to wounded veterans, children who lost fathers, and neighbors who lost sons. Americans in big cities and small, participate in displays of the intrinsic love so indicative of the American spirit.” |

In 1944-45 Lithuanians were forced to realize that the bloody World War II had been replaced by a new war, the longest and bloodiest guerrilla war in modern European history, lasting from 1944 to at least 1953. |

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

The West ignored all Soviet abuses!

- Posted by - (4) Comment

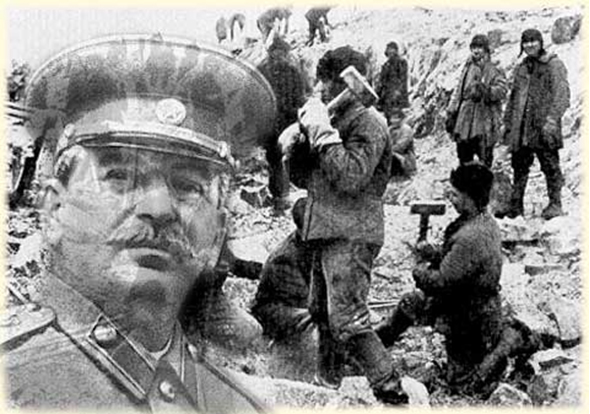

Joseph Stalin (1878 – 1953) One of the most powerful and murderous dictators in history, Stalin was the supreme ruler of the Soviet Union for a quarter of a century. His regime of terror caused the death and suffering of tens of millions, but he also oversaw the war machine that played a key role in the defeat of Nazism.

Illustration: http://sspurlock.wordpress.com

By Tony Olsson, North Devon, UK (guest blogger)

How could the western nations ignore the abuse by its wartime ally the USSR of all of the countries it had conquered during WW2?

Why didn’t America and Britain declare war on the USSR as its tanks and troops invaded Hungary, Czechoslovakia, and Poland?

Why was the attempt by Gorbachev to bring the Baltic States countries to heel by armed force ignored by the British press?

Why do western arms manufacturers sell guns and tanks and war planes to corrupt regimes that they know cannot act responsibly?

Why did the western nations not only not take punitive action against China for the Tiananmen Square massacre and on-going human rights abuses, but have put their countries in hock to China by closing down and moving the bulk of their manufacturing capacity to that country?

Why did NATO take so long to decide to act against Libya, and why hasn’t it acted against the rulers of Syria, Yemen, Zimbabwe and ... ? I could go on and on; the list is endless.

And why hasn’t action been taken against the rulers of Israel and Russia for the atrocities they are inflicting against other nations in the support of their own vested interests?

If Russia did invade in order to bring “its” Baltic republics back into the fold, would NATO come to their aid?

I was born the day President Roosevelt of America died a couple of weeks before the end of WW2, so have lived through, but mercifully have not been involved in any of the above conflicts. I can remember as an eleven year old, being very angry that Britain and America did not go to the aid of Hungary in 1956. The invasion of Czechoslovakia produced the same reaction, but was tempered by the bizarre coincidence that on the day the USSR invaded, I was at a concert in Norwich, England, given by the USSR State Symphony Orchestra conducted by Maxim Shostakovich. I think his father’s 5th Symphony was one of the works performed.

Sadly the answers to the questions boil down to VESTED INTERESTS.

A fear of WW3 is always at the back of the mind, but none of the major conflicts since 1945 has gone that far. It can’t be ruled out though..

So ultimately it comes down to smaller scale vested interests, all of which revolve around money: the arms manufacturers who don’t care who gets killed as long as they make a profit; the financiers who make money by investing money with firms who do business with corrupt regimes; the manufacturing bosses who put thousands out of work because they will make bigger profits if they move production to other countries (and I’m not talking just about China here); the politicians who will not act against a corrupt regime because that could result in reprisals against the organisations doing business with the corrupt regime; the group of countries that will not support a member that wants to act out of line, or even an enlightened politician who has ideas out of line with the prevailing majority (as a former USSR republic you know only too well what I am referring to).

Sorry to be a pessimist, but I see no end to the suffering. But to Aage Myhre and everyone who has suffered and is suffering pain because of past and present injustices, all I can say is the problems were too big to be dealt with at the time, and many are too big to be dealt with now. But be reassured by the fact that the tyranny of Stalin and his neo-Nazi version of Communism came to an end eventually. Patience rather than mental agonising and reprisals can win, even though it will be painful at the time. Wisdom to judge when a course of action can achieve the desired result is useful, as is the bravery needed to take a stand against injustice.

Tony Olsson

10 Oxford Grove, Ilfracombe, North Devon, EX34 9HQ, UK

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - (11) Comment

The longest and bloodiest

partisan war in modern Europe

LITHUANIA, LATVIA & ESTONIA 1944 – 1953

Text: Aage Myhre, VilNews Editor-in-Chief

Lithuanian 'forest brothers' from the so-called "Vytis" military district.

Pictures: Mostly from the KGB Museum in Vilnius

Tell a Lithuanian that his country was liberated and that peace after WWII was restored on the 9th of May 1945, as the Russians claim. Tell him that this May 2011 it is 66 years since the Soviet Union and the Western world defeated Hitler's Nazi regime, and that Lithuania since then has been a free, happy country in line with what other European countries experienced after they were occupied in 1939 – 1940 and liberated in 1945. Do not be surprised if you get an angry and annoyed look back. For while we in the Western world, in Russia and in other parts of the world joyfully could celebrate the liberation and the recovered freedom after the World War, Lithuania, the other two Baltic states, and Ukraine were forced to realize that one war had been replaced by a new, much bloodier and more protracted war, lasting from 1944 to at least 1953. What we in the west celebrated in May 1945 was by Lithuanians and the other occupied countries experienced only in 1990 –1991.

The end of World War II saw a Germany dramatically reduced in size. Before long it was also divided into East and West. Germany's defeat meant that Poland and Czechoslovakia returned to the map of Europe after a six-year absence. But not so for Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Ukraine and northern East Prussia (Kaliningrad) that all remained occupied by the USSR.

Western radio stations told us, who were lucky enough to grow up on the western side of the iron curtain, thoroughly about the Hungarian uprising against the Soviet intervention in 1956, an uprising that resulted in 2,500 Hungarians and 700 Soviet soldiers losing their lives.

Western television stations showed us in detail what happened when Czechoslovakia was invaded in 1968 by more than 200,000 troops from the Warsaw Pact countries Soviet Union, Poland, East Germany, Hungary and Bulgaria - with the outcome that 72 Czechs and Slovaks were killed when they tried to resist.

However, we got almost nothing to know about the many, many times bloodier uprising against the Soviet that was happening right outside our own front door, in the Baltic States, through nine long years from 1944 to 1953.

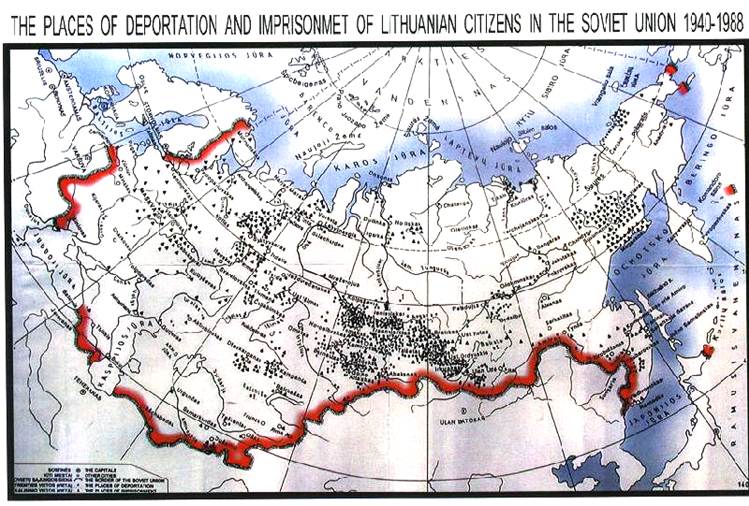

It is estimated that approximately 30,000 Balts and 100,000 Soviet soldiers died in this bloody guerrilla war when Estonians, Latvians and Lithuanians withdrew into the woods to organize its powerful armed partisan resistance after the Soviet Union at the end of the second World War, in 1944, pushed the German forces out, and Stalin decided to incorporate the Baltic States into his powerful autocracy instead of giving these countries their freedom and independence back. Today we know that this tragic, involuntary occupation and oppression was to last the whole 47 years, from 1944 to 1991.

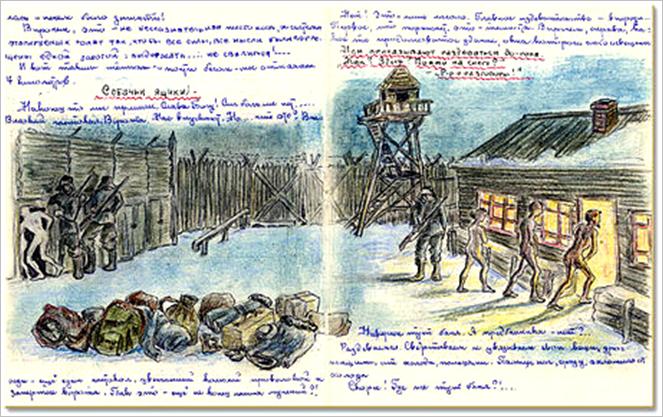

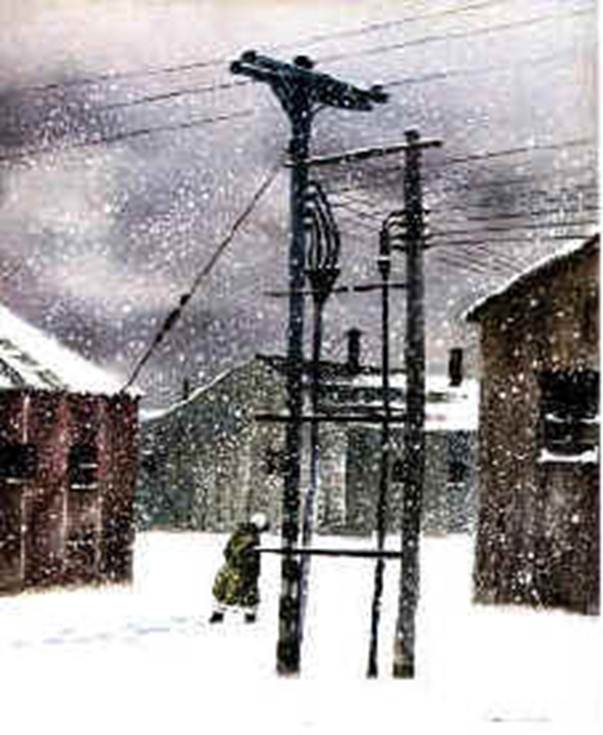

Entering a Siberian Gulag (leaf from Eufrosinia Kersnovskaya's notebook). During the period 1940 – 1953 Stalin’s Soviet deported approximately 600,000 individuals from the Baltic States to Siberia. Around 100,000 of them never returned to their homelands.

In addition to the 30,000 Balts who died in direct combats with the Red Army during this nine-year guerrilla war, comes all those who died in or on their way to Siberia, all because of their resistance to the Soviet raids home in the Baltics. It is considered that Josef Stalin was responsible for the deportation of not less than 600,000 Baltic people to the permafrost concentration camps and the gulag prisons during these years, and that probably as many as 100,000 of them died during the stay or during the three-month journey where they were stuffed into icy cold, miserable cattle wagons with thin straw mats as mattresses, and very limited food rations to survive on during the long way to the cold hell, thousands of kilometres north and east.

We speak, in other words, about an almost unimaginable and too little known purges of totally 130,000 people from the Baltic States during the very first years after the Second World War. But let us not forget that also the approximately 100,000 Soviet soldiers who died were victims of the same madness that almost a quarter million people were exposed to by an inhuman despot, still by many is regarded as a hero in Russia, Georgia and other former Soviet republics. The despot Adolf Hitler almost pales in comparison.

In comparison, 58,000 Americans died during the Vietnam War in the years 1960-75, and we were all fed with regular updates on how the war evolved, almost minute by minute.

The distance between the free, western country of Sweden and Lithuania is less than 300 kilometres, shorter than the distance between Vilnius and Klaipeda. But despite the short distance, there was remarkable little information that reached the West about the tragic carnage that took place so close to our own front doors after the war.

We probably had enough to lick our wounds after five years of occupation and the World War II. Even today there are very few people who know much about the bloody Baltic guerrilla war. This is, for example all my Norwegian Encyclopaedia gives of information:

"The armed resistance against the Soviet regime took the form of guerrilla groups in the forests (forest brothers) and had a large scope. Only in 1953 the armed resistance ebbed out. "

Lithuania’s WWII: Torn apart by two super powers.

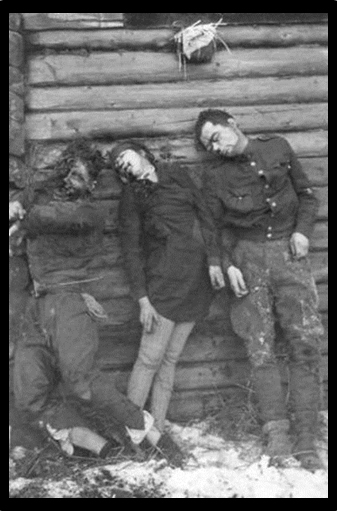

Many of the partisans were young men returning to Lithuania from the West after WWII to fight for their beloved home country. Here are three of them, with their official and nick names: K. Sirvys - "Sakalas", J. Luksa - "Skirmantas", B. Trumpys - "Rytis". Very few ‘Western partisans’ returned to the West. Almost all of them were killed by the Soviets.

Partisans, or "forest brothers" as they called themselves, were found in all three Baltic countries, but it was in Lithuania that the major groupings were found. It was also here that the really huge death tolls came. It is considered that 22,000 partisans and 70,000 soldiers from the Red Army and NKVD were killed in Lithuania alone, this in addition to the approximately 60,000 Lithuanians who died in Siberia during the early post war years.

The Lithuanian partisans usually appeared in uniforms, with national insignias and identification of rank as like other nations' armies. It is said that the Lithuanian soldiers always saved the last bullet for themselves; they knew all too well that torture, a symbolic trial and execution by hanging, head shot or group execution awaited them if they were captured.

The post war Guerrilla War in Lithuania is normally divided into three different phases:

- The first phase lasted from July 1944 to May 1946, with violent skirmishes and casualties on both sides. More than 10,000 forest brothers lost their lives in battles and skirmishes during these two years. Partisans captured during this period small towns from the Soviet forces, local quisling units were disarmed and the occupants’ offices were destroyed. But the big losses meant that tactics had to be changed.

- The second phase lasted from May 1946 until November 1948. The Lithuanian units were then divided into smaller groups that hid in well-camouflaged bunkers. During this period a joint command was established for all Lithuanian forces fighting against the occupying army. Contacts were also made contacts with the West in this period, but no help arrived.

- The final phase lasted until May 1953. And despite the brutal oppression and forced collectivization, around 2,000 partisans were still active with their armed resistance against the occupation. During this period, they also worked extensively with informing the Lithuanian people by publishing newspapers, books and leaflets. Circulation varied from a few hundred to 5,000. Such publications lasted until 1959.

There were also parallel battles against Soviet forces in Estonia and in Latvia, but in much smaller scale. Only in Western Ukraine, there was fighting in the same scale as in Lithuania.

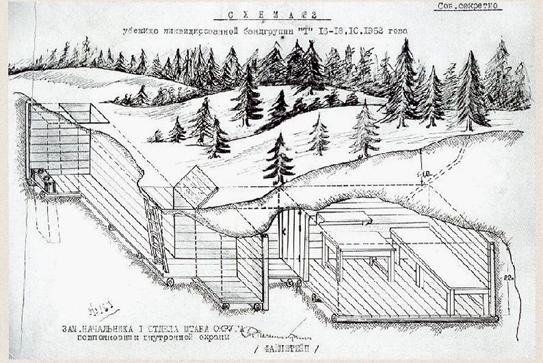

The Forest Brothers often used cellars, tunnels or more complex underground bunkers as their hideouts, such as the one depicted here.

The Baltic Partisan War came mostly to an end by May 1953, two months after Joseph Stalin died. But the last active resistance man in Lithuania shot himself, rather than surrender, as late as 1965, and the last partisan did not come out from his hiding place before 1986, 42 years after the guerrilla war in the Baltics started.

In 1955, the Soviet-controlled 'Radio Vilnius’ offered amnesty to all the partisans who were still hiding in Lithuania's deep forests, and in 1956 the KGB repeated a similar provision. Such amnesty-deals were of course meant only to lure the last forest brothers, so when the famous partisan leader 'Hawk' was taken that the same year, he was immediately given a symbolic trial and executed. Hawk was an American-born Lithuanian who had returned to his home country to fight the Soviet occupation.

Instead of giving themselves over to the Soviet occupiers, many chose to commit suicide, often by exploding a grenade right in their own faces in order to destroy them so much that they would not be identifiable and thereby create a risk to their relatives' lives. Such suicides occurred until around 1960. Many also managed to obtain false identity and get back into society without being detected.

Many of the Soviet Union's atrocities against the Baltic States have only come to light in earnest after 1991 when these countries regained their freedom and independence. A large part of the archives that mentioned the said matters were, however, brought to Moscow to prevent the World from having access to these highly revealing documents.

But, strangely, in 1994 a former KGB officer decided to go to the Lithuanian authorities with detailed information about how torture and executions had taken place at the KGB headquarters in the Vilnius city centre. He told that there had been secret burials for the victims, just on the outskirts of Vilnius. When the huge mass grave he had told about was found and opened, several hundred corpses of partisans were discovered, all in Lithuanian uniforms, and all obviously tortured to death.

One can ask whether it was a fatal mistake for a small country like Lithuania to so aggressively a predominance they had to understand they would not be able to defeat. Admittedly, there is a general perception that Lithuania thereby was avoiding most of the ‘russification’ that Stalin and later leaders implemented in all other Soviet republics. The Russians were simply too afraid of the Lithuanians as a result of the strong opposition during the post-war years, hence the proportion of Russians in Lithuania today represents only 6% of the population, compared to more than 30% in Latvia and around 25% in Estonia.

But the bloodshed in the Baltics, and the incredibly extensive deportations to Siberia, as a result of the partisan opposition, made that these three countries lost too many of their best men and women. The hero status they may have achieved around the world never became significantly large. We in the West did not know what really happened, and when we finally learned, far too many decades have passed to achieve a proper attention for the heroes, the very guerrilla war, the deportations and the unbelievable sufferings the Baltic people underwent on the Siberian permafrost during the 1940s and 1950s.

Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia have paid an extremely high price for their rebellion behaviours, and are unlikely ever to receive the honour and the redress they deserve for their courage to fight the injustice they were subjected to during the ruthless Soviet period.

When World War II ended, the West chose to forget Lithuania

The historic meeting near the end of World War II, the Yalta Conference, became fatal for Lithuania. It involved three key allied leaders. Left to right: Winston Churchill, Prime Minister of the United Kingdom; Franklin D. Roosevelt, President of the United States; and Joseph Stalin, Premier of the Soviet Union.

For several years after World War the Balts believed that the U.S. and other Allied powers would come to their rescue and help to free them from the Soviet occupation. This was fatal.

The partisan leaders were familiar with the Atlantic Charter, which was signed by Churchill and Roosevelt 12 August 1941 aboard the U.S. cruiser Augusta in Newfoundland, a charter later acceded to on 1 January 1942 by all countries involved in the war against Germany and Japan - including the Soviet Union. This declaration stated that all territorial changes resulting from the war would only take place after the population's own desires, and that any people should have the right freely to choose their form of government.

What the Baltic people did not know, was that their case head was not at all discussed when the British Prime Minister, Winston Churchill, the U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt and the Soviet leader Josef Stalin in February 1945 met in the city of Yalta on the Black Sea to lay the conditions for peace and the post-war period. The Baltic States were totally forgotten; but they did not know about it, and therefore continued the impossible fight against the evil superior force until 1953.

It has been speculated that Roosevelt's failing health may have been the reason why Stalin so easily got the upper hand at the Yalta Conference. The outcome was, in any case, very tragic for the Baltic States, and only in 2005 the American president, George W. Bush came here to apologise on behalf of the United States. Russia’s President, Vladimir Putin, was also asked to apologise for the atrocities against the Baltic States in the years after Yalta. But Russia still considers that they 'liberated' the Baltics and sees no reason to excuse themselves. It went even so far that Putin declared Lithuania's President Valdas Adamkus 'persona non grata' after the latter refused to come to Moscow to participate in Russia’s anniversary celebration of the Soviet victory over Nazi Germany on 9 May 2005.

In the years after WWII a number of Lithuanian agents were amazingly capable of getting in and out of the country several times, and in December 1947 a full delegation travelled to Western Europe to present their case to the Pope and to Western governments. But no countries or leaders dared go into conflict with Stalin's Soviet Union, and Lithuanians call for help was largely met with deaf ears.

Though not quite. Both U.S. and UK intelligence agencies gave their orders to see what might be done to create secret anti-communist organizations and operations behind the Iron Curtain. They also helped to organise the radio stations 'Radio Liberty' and 'Radio Free Europe', which for many years thereafter conveyed useful information to the Baltics. In 1951 came the 'Voice of America' on air, and thus gave hundreds of thousands of Baltic war refugees in the United States a voice back to their home countries at the Baltic Sea.

Unfortunately, the success of the Western intelligence services and their 'relief efforts' very much failed, which in retrospect largely is attributed to the British intelligence officer Kim Philby, the man who in reality was a Soviet spy who unfortunately contributed so actively to the killing of tens of thousands of Baltic people.

The intelligence organizations' attempts to help the Baltic States irritated Stalin violently, and he therefore imposed increasingly tough measures against the uprisings. His NKVD (later renamed the KGB) had more or less free hands to exercise extensive torture against individuals and groups believed being in league with the partisans. Vague suspicions were enough to allow use of cruel torture methods. Many were hanged or shot without any real form of litigation. A huge number of relatives and family members of the partisans were sent to slave labour camps in Siberia. All private farms were incorporated into collective farms to prevent them from continuing to provide food to the partisans, and many farmers were deported to Siberia. The West's attempts to help got quite the reverse effect. Tyranny had triumphed, and our close neighbours on the Baltic Sea's south coast were once again suffering in a most cruel way.

One of the many killed Lithuanian partisans,

Juozas Luksa – "Skirmantas", "Daumantas",

after his death on the 4th of September 1951.

Photo: KGB

Few in the West know that Lithuania 500 years ago was considered Europe's largest country, stretching from the Baltic to the Black Sea. Few in our today's West know the proud and honourable cultural history of the Baltic countries, or that these countries were economically fully on par with Scandinavia until World War II, and few know about the heroic guerrilla war these three nations fought against the mighty Soviet Union after WWII.

During five world war years, the Baltic area became the incredibly bloody and sad battlefield where Stalin and Hitler pushed each other back and forth, with fatal and almost incomprehensible destruction and murders of hundreds of thousands innocent people as result. It was here that the Holocaust saw its very worst outcome on Earth, when 95% of the large Jewish population of Lithuania was exterminated. It was here that Europe's longest and bloodiest guerrilla war and the ensuing mass deportations to Siberia took place through more than a decade during and after WWII.

Hundreds of thousands of our closest neighbours died just outside our own front door (or were deported to the gulag camps in the permafrost of Siberia). These terrible things happened only 300 kilometres away from Lithuania’s closest Western coast, at the same time as we westerners celebrated our new freedom and the beginning of the new era we today know as the proud, free Western World.

Didn’t we in the West know, or did we prefer not to know?

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - (2) Comment

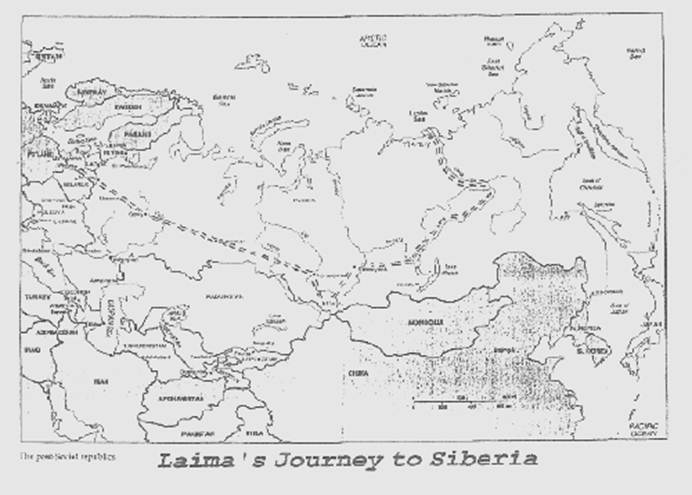

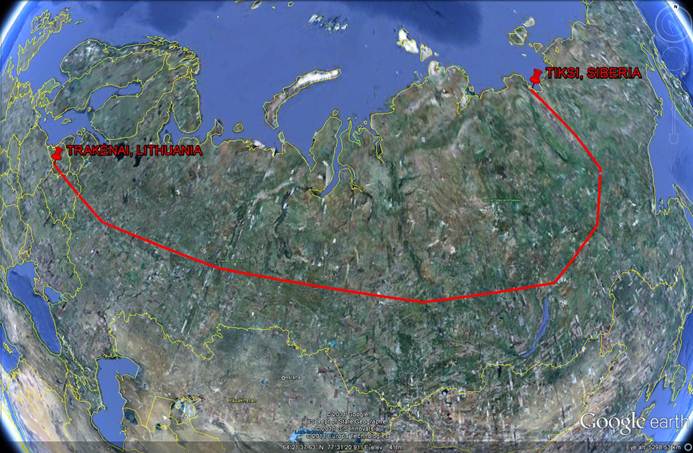

CHRISTMAS IN SIBERIA

A story about a Lithuanian family

deported to the Lena River delta.

North Siberia, year 1942

Text: Leona T. Gustaff

“The tents were freezing cold, harsh, and distressing; so, the adults decided to build better living conditions. "We can build barracks," said one Lithuanian, "We can catch the logs in the Lena River." The men waded barefoot into the icy water, caught floating logs, brought them to shore, and built the barracks. They covered the outside walls with snow and ice which they learned would help keep out the frigid temperature. They also found a large iron stove, which they placed in the middle of the building.”

|

Laima's Story The house was warm, secure, peaceful. The window drapes had been closed tight to shut out the rising sun. On June 14th in 1941 we were not aware of the tragedy about to enter our lives. A thick, fluffy comforter covered me and kept me safe. Tėtė and Mama slept quietly in the adjacent room. Algis, my three-year-old brother, was in sound slumber in his trundle bed. Suddenly, at 5 a.m., sharp staccato raps at the entrance of our home aroused us. "Guzevičius, wake up! Let us in! We are the militia!" Tėtė grabbed his robe and slippers and rushed to the front entrance with my Mama, brother and me running close behind. When he opened the door he encountered two men standing on the steps leading into the house. One was dressed in a Russian military outfit; the second was a friend, Dabulavičius, who lived nearby in the village of Brazavo. "Labas," Tėtė, startled and not prepared for what was to follow, greeted the men. The military man, a member of the Russian armed forces, grabbed him by the shoulders, pushed him back into the room, swung him around quickly, clasped his hands to his back, and shackled him with metal hand-cuffs. My brother and I were frightened and bewildered. We were sobbing aloud as Mama pulled at the arms of the soldier and begged him to tell her of what my father was guilty. "Dabulavičius," she pleaded, "Please tell them not to do this. Stasys has never hurt anyone. He is a good man and does not deserve this kind of treatment. He has even lent you a large sum of money recently so that you could build an addition to your home." Dabulavičius stood by silently and turned his head away so that he would not have to look at my mother. "Tylėk!" The soldier, pushing Mama aside, ordered her to be silent. "Pack whatever you think the entire family will need for a long journey. Your baggage must be less than 120 kilograms."

The Times At that time the Soviet Union was in total control of Lithuania. Russian military leaders were aware that 175 divisions of the Third Reich's Wermacht were advancing toward the Soviet Union's western frontier. The soldiers would have to travel through Lithuania. There had been rumors that Bolshevik militia was gathering educated Lithuanian men and army leaders to incarcerate them in prison or exile them to a foreign land. In order to receive gifts from the military or, in some instances, to save their own lives, neighbors had been approaching the Soviet officers and volunteering evidence of conversations that they had witnessed of discontent with the political regime in power. These were generally trumped up falsehoods. Tėtė then realized that his friend had conjured up treacherous untrue charges about him. Only eight days later, on June 22, the Germans attacked the Soviet Union forcing the Red Army to withdraw from Lithuania. Unfortunately, we were already on a desperate journey to an unknown destination. Tėtė, my father, was a teacher in the Kalvarijas district. He was born in 1894 in Suvalkija, not far from the town of Punskas, the third in a family of eighteen children, nine of whom were either still born or died soon after birth. He had attended Primary and Secondary schools in Lithuania, received his university education in Russia and returned to Lithuania to teach in Kalvarija. He spoke six languages -- Polish, German, Russian, French, Jewish, Lithuanian -- was the owner of an extensive library with thousands of books, and had founded and promoted new elementary schools in the Marijampolė district. Active in the community, a leader in the Kalvarija area, he had organized and taught both children and teenagers many different traditional dances. He enjoyed farming, fertilizing the land, and planting seeds to grow potatoes, carrots, and cabbage. He also propagated apple trees. He never imbibed liquor, despised alcoholics, and launched programs against alcoholism. Tėtė was 33 years old when he married my mother, who was only seventeen years of age. But Mama possessed great physical strength, loved to read, and had lively intelligent conversations with him. She and Tėtė together had purchased a home in Trakėnai from a German nationalist who was returning to his country. Trakėnai is located about five kilometers south of Kalvarija. It initially had been a large German estate, but eventually was divided into small parcels of land for German families. They bought the property, which consisted of a home and barn with land for farming. Each month they sent a sum of money to the original proprietor, who according to country laws, was the true owner until the entire amount of the sale was paid. The Beginning of the Journey Mama quickly gathered warm clothing and made small bundles for my brother and me to carry. She snatched the feather comforters from the beds and collected coats, sweaters, socks, and boots. She packed potatoes, cheese, sugar and flour, which she and my father carried. Soon, a truck filled with other Lithuanian families roared to a stop in front of our home. Mama, Tėtė, Algis, and I climbed into the back of the vehicle and searched for an area to put our hurriedly collected bags. My parents held us tight and comforted us as they wiped away our tears. The truck continued on its route until we reached Kalvarijos Railroad Station. When we arrived at the station we were surprised to see a large group of people who also carried bundles of hastily collected clothing, food, and bedding. There was noise and considerable agitation. Children cried, sobbing aloud. People talked incessantly, looked for friends, made sure certain family members were not separated, and asked each other if they knew where they were going. Everyone was frightened. No one knew the answers. Tėtė met a friend. "Ulevičius, what is happening here?" "I'm not sure, but haven't you heard the rumors?" "That educated Lithuanian men would be put into prison or exiled to Siberia? Yes, I had heard but it is difficult to believe that Communists would be so cruel." "Speak softly, my friend, so as not to be overheard. We must be careful. We cannot trust anyone." We were pushed into straight lines and commandeered into freight cars -- actually into cattle cars -- that formerly had carried farm animals from the villages to the cities. People were jammed together. Soldiers shoved more men, women, and children into already overcrowded cars. Everyone looked for an area on the floor where they could put their belongings and perhaps sit down. My parents found a small spot where we could huddle together and keep our bundles of clothing and blankets close to us.

The Train of Horrors The train began to move slowly and then picked up speed. Trapped in boxes with boarded up windows we moved through our beloved nation quickly. We could only imagine the clear natural lakes, boggy swamps, small working farms, and forests of birch, pine, and spruce trees that we passed. I don't believe any of us realized that this would be our last journey through the Lithuanian countryside for many years. How could we possibly know that some of us would never see this land again but would die and be buried in strange, inhospitable territory where we would suffer bitter cold, hunger, and absence of the ordinary needs and comforts of our existence? We were thirsty when we made our first stop at Kaunas. Crying children begged for something to drink. "Look, they're bringing water," a woman on the train shouted. She had noticed a soldier carrying a pail of water and walking towards our train. Everyone rushed to the door that was a little ajar. Mama reached out to take the pail of precious water from the soldier but he, fearing she wished to escape, angrily banged shut the door, which hit her on the head and knocked her down. She fell to the hard floor into a dead faint. "She did not awaken from this unconscious state for the next five hours." my father told me years later. Until the end of her life she had very painful headaches. From Kaunas the train began to move slowly towards the Russian border where for the first time we were given food: watery gruel and a small piece of black bread. Traveling in a daze suspended by time, we learned we were on the Trans-Siberian railway and feared we were on the way to Siberia. Years later Onutė Garbštienė, who was also deported in 1941, published her diary, which described some of the difficulties we had encountered: "Suddenly the hammering of axes echoed down the length of the train. We shuddered as if hit by a charge of electricity! They were boarding up the windows, so the "wild beasts" wouldn't escape from their cages. Some other people climbed inside. They made holes in the walls, to the outside, and also cut a hole in the floor, for our toilet. Everything was so degrading, horrifying, and shameful. Who has ever heard that men and women, crowded into this single area, had to take care of their personal needs in front of each other! We got used to the shame but not to the stench. The stench was unbearable because many, especially the children, were suffering from diarrhea caused by drinking contaminated water. Not everyone was able to make it directly into the hole. Soon the edges became encrusted with excrement. We couldn't even sit down. We started using a chamber pot, but the stench was even worse. Later we begged and were given permission to take care of this matter wherever we stopped. All shame evaporated! Everyone would squat under the cars and relieve themselves. Constipation was a problem. Suddenly: "Hurry up! Get back inside!" Everyone would run back to their assigned cars with their clothing in disarray! And this went on for the duration of the trip." Our journey lasted three weeks. Parents were exhausted. Children were tired, moody, and restless. Everyone slept on whatever makeshift accommodation they could make on the floor. Some slept on their baggage. Some were fortunate to have blankets or feather comforters. The daily ration of watery gruel and small slice of rye bread was not enough to satisfy hunger, and many were ill. The perilous trip posed severe difficulty for infants and some died in their grieving mother's arms. Soviet guards tossed them into the woods without benefit of a burial. The First Stop Eventually we reached the Altay, a sparsely populated mountainous territory in South Siberia, close to Northwest Mongolia, China, and Northeast Kazakhstan. About three times the size of Lithuania, it contains a dense pine forest, which extends into the Altay Mountains. We lived there for the entire winter. Mama and Tėtė were forced to walk about five kilometers through dark forests to the trees they were ordered to cut. The soles of their boots were worn through, and they covered their feet with rags to help them suffer the ice, twigs, and other debris they walked through on their tortuous journeys. Tėtė was not accustomed to such labor, and each evening his body was filled with pain; his fingers so frozen that he could not bend them. He longed for his library of books. Newspapers, journals, or written materials of any kind did not exist among these people. The only news we received was by word of mouth -- sometimes hopeful, sometimes sad, but always difficult to believe since the source was unknown. We were still fed only bread and watery soup. We Move On In 1942, at the first signs of summer, we were gathered into trucks and transported to the Lena River, where we were forced to clamber into large barges, heavy wired cages that had been built to transport prisoners. Armed guards patrolled us constantly. The adults again began to wonder where we were going. "Perhaps we are going to America," said Mr. Abramaičius, the father of a family we had befriended while living in Altay. We were not taken to America but instead, we entered a hellish situation; recollections of which sicken our hearts and spirits and we don't want to remember.

Slowly we sailed down the Lena River. We passed 'taiga' -- forests of pine, larch, spruce, and birch. We fought legions of biting insects, mosquitoes, and gnats. At times we caught sight of reindeer. "Those woods must be full of mushrooms," Abramaičius mentioned to my father. The thought of this delicacy that flourished in the birch woods in our native land brought a sense of sorrow and longing. We traveled until we reached Trofimovska, a fishing village on the river near the Arctic ocean, not far from the Laptev Sea. We settled in the town of Tiksi. The adults were ordered to pitch tents, the only shelter available. Winter temperature dipped down to minus 40 degree F; summers seldom reached plus 50 degree F. Our bodies were not conditioned to live in severely cold climate.

We were fortunate that Mama had taken feather comforters so that we were able to weather the cold somewhat. Others did not even have blankets. Many became ill and quite a few passed away from malnutrition and the frigid environment. Entire families died. The dead were interred in the unfriendly foreign soil. We hoped that someday their bodies might be returned to their beloved Lithuania. Daily Life Continues The tents were freezing cold, harsh, and distressing; so, the adults decided to build better living conditions. "We can build barracks," said one Lithuanian, "We can catch the logs in the Lena River." The men waded barefoot into the icy water, caught floating logs, brought them to shore, and built the barracks. They covered the outside walls with snow and ice which they learned would help keep out the frigid temperature. They also found a large iron stove, which they placed in the middle of the building. About 10 or 15 families moved with us into the barracks, but we were not destined to be comfortable very long. Soon, we were attacked by a common enemy found all over the world -- lice! We found them everywhere -- in our beds, on the floors, in our clothing. They attacked our hands, our faces, and our legs. We found them in our hair and all over our bodies. No one was safe from the lice. In Trofimovska there was nothing available to help us get rid of them. We had to kill them with our own hands. The only food available was fish from the frozen Lena River. Mama and Tėtė organized a group of Lithuanians into a fishing brigade. After drilling a few holes in the ice, they'd put bait on lines, which they lowered into the openings. They sat for hours waiting for signs that fish had snatched the bait, and we had more substantial food to add to our meager supply of bread. During the second winter in Trofimovska, weak from hunger, I was not able to walk, and I lay in bed for two months. My brother Algis was also in poor health. His teeth began to decay. More Lithuanians died from the hunger and cold. I don't know how we were saved from death. I remember that Mama sold her wrist watch to a Jakutian native for 30 kilos of black rye flour. She made 'lepioskas', and as we ate the mealy pancake we became stronger. Sometimes Tėtė still caught some fish, but eventually the Russian brigadier leader did not permit him to bring the fish home. This was our most difficult winter. We never had enough to eat, and we were always cold.