THE VOICE OF INTERNATIONAL LITHUANIA

|

VilNews has its own Google archive! Type a word in the above search box to find any article.

You can also follow us on Facebook. We have two different pages. Click to open and join.

|

Historical Lithuania

- Posted by - (1) Comment

Main events in

Lithuania’s history

(based on “The official gateway of Lithuania”, Government of

Lithuania website, adopted and modified by dr. S. Backaitis)

PRE-HISTORY OF LITHUANIA

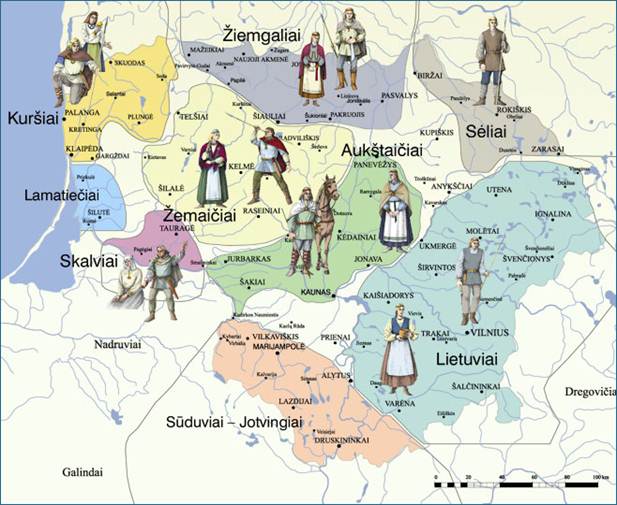

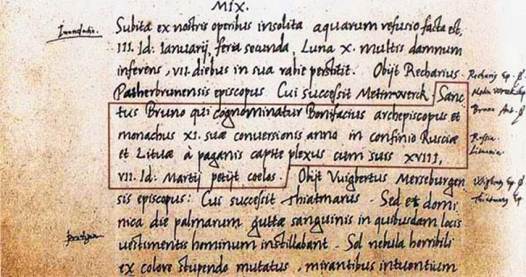

The first settlers arrived at the eastern shore region of the Baltic Sea in approximately 12, 000 B. C. In 3,000–500 B. C., the Indo-European Balts came to live here. Between the 5th and 8th centuries tribal groupings in the western territories included: Prussians, Yotvingians, Curronians, Zemgalians, Lithuanians and Latgalians. In the 10th century the pagan Baltic tribes became the target of christianization by Western Europe. In 1009, the name of Lithuania was mentioned for the first time in the written account of the mission of St. Bruno in Quedlinburg Annals.

Baltic tribes - circa 1200 AD

Lithuania (Litua) mentioned in the Quedlinburg Annals in 1009

CONSOLIDATION AND CHRISTINIZATION

Early Second Millenium

The first major battle known in Lithuanian as Saulės mūšis was fought on September 22, 1236 between the Livonian Brothers of the Sword and pagan Samogitians. The Sword-Brothers, the first Christian military order established in the Baltic lands, were soundly defeated and its Grand Master, Volkwin killed. The remnants of the Order incorporated into the Teutonic Knights Order in 1237. The defeat ended forever some thirty years' worth of conquests by the Livonian brothers of the Sword on the south bank of the river Daugava. The defeat inspired rebellions among the Curonians, Semigallians, Selonians, and Oeselians tribes previously conquered by the Sword-Brothers.

Lithuania, as the Grand Duchy (Magnus Ducatus Lithuaniae), was first noted in documents, with Mindaugas coronation as the king. He consolidated a number of Lithuanian related tribes and was crowned on July 6,1253. The Papal Bull granted Lithuania the highest title of monarchy, which meant that the pagan country was recognized and accepted into the family of Europe’s Christian nations as kingdom. However, Mindaugas was assassinated in 1263, the monarchy disintegrated and the people reverted to paganism.

Upon several decades of internal feuding, Gediminas (1316-1341) emerges as king of pagan Lithuanians and many Russians and as Duke of Zemgalians. Under his rule Lithuania grew strong. He chose Vilnius as Lithuania’s capital, and invited artisans and learned people from other parts of Europe to come and build the city. With the campaign of Gediminas into the lands of Kiev and Volhynia (1320–1321), the Jewish inhabitants of these territories were invited to come and bring their skills to the northern provinces of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania.

While Gediminas was in power, Lithuania expanded east and south into what are now the lands of Belarus and Ukraine. However, Lithuania as a pagan nation was facing a growing threat from the Teutonic Order, a military organization of German knights, who crusaded by sword to christianize the pagan population of the eastern Baltic region.

In 1363 Gediminas' son Grand Duke Algirdas soundly defeated the Golden Horde in the Battle of Blue Waters liberating Kiev from the rule of Tatars and ending their threat to Western Europe.

In 1377 Jogaila, the grandson of Gediminas and the son of Algirdas, became the Grand Duke of Lithuania. In 1381 he was forced by his uncle Duke Kestutis to flee Vilnius, declaring himself as the Grand Duke of Lithuania. However, in 1382 Jogaila seized power in Vilnius while Kestutis was away. He captured Kestutis, who was subsequently assassinated in captivity. His son Vytautas escaped.

In 1386 Grand Duke Jogaila married Jadwiga the teenage queen princess of Poland. The Polish Sejm (parliament) elected Jogaila as the king of Poland. Jogaila accepted Christianity, and most of his subjects in Lithuania were induced, many times by threat of death, to convert to the king’s religion.

Inasmuch as Jogaila was based in Poland and was too distant to rule Lithuania effectively, he made peace with Vytautas in 1392. Vytautas (1350-1430) assumed the title of the Grand Duke of Lithuania on the condition of his allegiance to and support of Jogaila.

With the official adoption of Christianity in 1387, Lithuania followed the Western path of development. In the years following, Lithuania saw the spread of written language, opening of schools, and Lithuanian students travelling to study at European universities.

MIDDLE AGES

From the Baltic to the Black Sea

An important victory in the Battle of Žalgiris (Grünwald-Tannenberg) in 1410 was achieved by the allied forces of Lithuania and Poland. The Order of Teutonic Knights was decisively defeated. After the war, the Grand Duchy of Lithuania under Grand Duke Vytautas reached the peak of power, with its territory stretching from the Baltic to the Black Seas and from the borders of Poland to Smolensk. It emerged for the next century and a half as an important political power in Eastern and Central Europe, thwarting the expansion of the Muscovites from the east and the Tatars from south.. The success of the expansion of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania was essentially based on ethnic and religious tolerance and protection from external enemies. A charter of privileges, which was momentous in the subsequent history of the Jews of Lithuania, was granted by Grand Duke Vytautas, first to the Jews of Brest (July 1, 1388) and later to those of Trakai, Grodno (1389),

Lutsk, Vladimir, and other large towns.

Grand Duchy of Lithuania in the 13th-15th Centuries

Lithuanian Statutes and First Constitutional Document in Europe

The Lithuanian Statutes were developed in early 16th century to serve as the legal framework for the Grand Duchy. The legal thought reached further heights at the end of the 18th century when a Constitution of the Commonwealth was adopted on 3 May 1791. It was the first constitution in Europe (preceding the French Constitution), and the second in the entire world.

The Oldest University in Eastern Europe

The beginnings of higher education in Lithuania go back to 1579, the year of founding of the Vilnius University as the Jesuit academy. Its foundation was the most significant event in the cultural life of the 16th century Lithuanian Grand Duchy, bearing high political importance. Vilnius University was the first higher school of education not only in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, but also in the whole of Eastern Europe

The Vilnius powers university

The Demise of the Commonwealth

To thwart the threats from rising powers of Sweden and the Duchy of Moscow, Lithuania entered in 1569 into a commonwealth union with Poland, which lasted until the very end of the 18th century. As a member of the Commonwealth, Lithuania retained its institutions, including a separate army, currency, and statutory laws. The Commonwealth up to the end of the 16th century was one of the largest kingdoms in Europe. However, the ruling Jagiellonian dynasty gradually lost control over the affairs of state to the more and more power seeking and self-serving nobility. After the death of king Zygimantas Augustas in 1573, the last of the Jagiello dynasty, the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth became an elective monarchy, a quasi-democratized nearly an ungovernable state.

The once powerful Commonwealth, incapable of controlling the feuding regional nobility, gradually lost the ability fight off the growing power and destructive invasions of neighboring kings. The demise was further amplified by a nearly a century lasting black plaque which wiped out more than half of the Commonwealth’s population. The Commonwealth began to seriously disintegrate in the latter part of the 17th century and was finally partitioned by Prussia, Russia and Austria in 1795.

LATTER PART of the SECOND MILLENIUM

Lithuania Under the Czarist Rule

Upon the third and final partition in 1795, the Commonwealth of Poland and Lithuania ceased to exist. Lithuania was annexed by Russia. In 1830, the Poles rebelled against the Russian rule and in 1831 the uprising spread to Lithuania. However, the Russians crushed the uprising within a year. In 1863 the Poles and the Lithuanians rose once more against the occupiers, but again they were defeated and brutally dealt with. Each rebellion was followed by severe repressive measures such as mass hangings, deportations, prohibition of Lithuanian schools and Latin print, as well as prohibition of public use of Lithuanian language. Russian orthodox religion was given preference over the Catholic Church in all walks of public life. Lithuanians, in hundreds of thousands, escaped Russian repression by emigrating to North America. Similarly, many thousands of Jews of the former Grand Duchy of Lithuania, calling themselves Litvaks, left for South Africa, North America, Australia, Brazil, Zimbabwe, Israel, etc. They formed strong communities around the world and hold top positions in politics, economy, arts and sciences, culture and society in general. They often lead in creativity and innovations that affect and influence the world we live. Their names are frequently found among the Nobel laureates and in many other honorable contexts.

Inspite of these oppressive Russian measures, there was a growing interest in Lithuania in its culture and history and the quest to be free of foreign intrusion. At that time nationalism was a growing force in Europe, and there was little the Russians could do to impede this development.

Book Smuggling – the Nineteen Century Phenomenon

Book smuggling emerged as resistance to the repressive actions of tsarist Russia authorities against the use in public of the Lithuanian language, the ban of Lithuanian books in Latin script and encouraging the population to accept the Russian Orthodox faith. Book smuggling activities involved the printing of books, mostly in the then Prussia (Lithuania Minor) and the United States of America, carrying them illegally into the occupied country and distributing them to the population. Though book smuggling was done mostly by ordinary peasants, this cultural movement, which was a reflection of the national quest for freedom, paved the way for the restoration of Lithuania‘s independence in 1918. This quest of preserving national identity, has retained great importance to this day. Inasmuch as book smuggling is often regarded to be Lithuania’s unique historical phenomenon of the 19th century, the UNESCO named it in 2004 as unique and unprecedented phenomenon in the world.

1918–1940: Period of Independence and Nation Building

On 16 February 1918, twenty courageous, determined and trusted representatives of the Lithuanian nation signed the Act of Independence “re-establishing an independent state, based on democratic principles, with Vilnius as its capital city, severing all previous links with other states.” Having withstood the fight for independence against Bolshevik and Polish invaders, Lithuania adopted parliamentary democracy in the Constituent Assembly (Steigiamasis Seimas) on May 15, 1920. Poles, breaking political and military agreements, seized on October 9, 1920, Vilnius and a sizeable part of eastern Lithuania. Kaunas became Lithuania’s provisional capital. In 1923 Lithuania exercised its claim over the Klaipeda (Lithuania minor) region by expelling the French military administration.

The historical tragic flight by American Lithuanians Steponas Darius and Stasys Girėnas, who were among the first ones in the world to fly a propeller plane in 1933 across the Atlantic from the New York city to the middle of Europe, and Lithuania’s win of the basketball championship of Europe in 1939, became national symbols of patriotism and pride in the young nation’s great achievements. The principles developed during this period such as the rule of law, civic society, cultural and historical values, national solidarity, drive for scholastic excellence and flourishing agriculture, helped Lithuania survive as a nation the subsequent 50 years of Soviet Russian occupation. In subsequent years of communist rule, these values served as ideological basis for resistance and restoration of Lithuania’s independence in 1990.

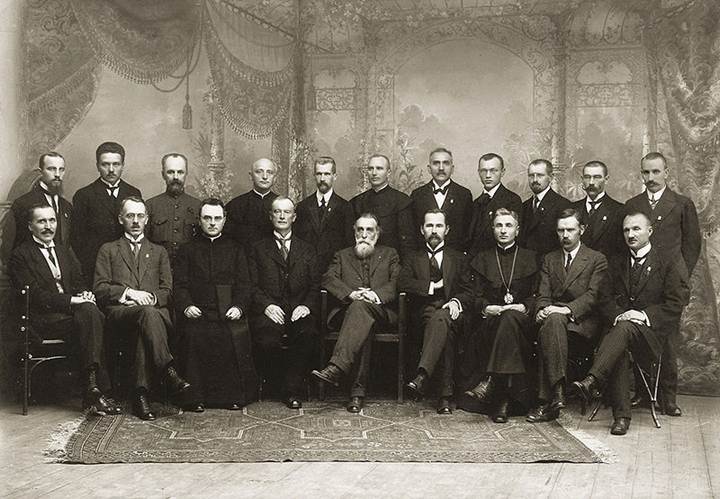

The signatories of Lithuania’s independence in 1918

Nazi Germany and Lithuania

Lithuania conducted in 1934-5 the first NAZI trial in Europe and defied Hitler’s threats of vengeance. In March 1939, a long-running dispute between Lithuania and Germany over the jurisdiction of the Klaipeda region came to a head when Hitler demanded that Lithuania gives up the region or face Nazi Germany invasion. Lithuania, failing to receive support from either USSR or Western European powers, gave in to the ultimatum. On March 22, 1939, Hitler triumphantly arrived in Klaipeda and declared victory.

Soviet Occupation and Annexation into USSR

In August 1939, under the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact, Hitler and Stalin agreed to carve up Central and Eastern part of Europe. The Baltic states were relegated under this agreement to the Soviet sphere of influence. Upon Soviet occupation of eastern part of Poland, Moscow returned Vilnius to Lithuania as a condition of stationing several isolated military garrisons on Lithuania’s territory. However, eight months later, USSR forcibly occupied Lithuania in June 1940 and formally annexed it as a Soviet republic in August 1940. Lithuania’s state structure was dismantled, followed by mass arrests, killing of politically unreliable, and began large scale deportations of the population to Siberia.

World War II and Subsequent Period June 1941

On June 22, 1941 Germany invaded USSR and as a result, it occupied all of the Baltic states. It imposed a military rule and political governance by Nazi powers from Berlin. Attempts by Lithuanians to restore their independent state was squashed within several weeks of occupation and their principal proponents were arrested and sent to concentration camps. The occupying Nazis and their local henchmen killed most of the 240 000 Lithuanian Jews.

Upon defeat of Nazi Germany in 1945, the Soviet Union reoccupied the Baltic states. Lithuania was restored as a Soviet Socialist Republic of the USSR. From 1945 through 1950s the Soviet authorities implemented deportations of several hundred thousands Lithuanians to remote areas of the USSR, mostly to northern Siberia slave labor camps (gulags). While more than half of the deportees perished, a number of survivers after enduring inhuman hardships in forced labor camps for some 20 and more years, returned to their homelands. During these turbulent years, thousands of the younger Lithuanians joined resistance groups to fight the communist occupiers for the country‘s independence. The period of the fight for freedom resulted in more than 30,000 deaths. It is one of the most dramatic, tragic but heroic events in Lithuania‘s history.

The Singing Revolution

The Initiative Group of Sąjūdis (Lithuanian Reform Movement), established in June 1988, inspired the nation with faith to quest for independence. Subsequently in 1989, the Lithuanian Communist party broke away from the Central Communist Party in Moscow, which was an unprecedented and very dangerous move at the time.

On August 23, 1989, the Estonians, Latvians and Lithuanians in a mass rally joined hands to form a human chain stretching some 650 kilometers from Vilnius through Riga to Tallinn The event marked the 50th anniversary of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, as a result of which the Baltic nations lost their independence. The Baltic Way was a symbolic expression of final separation of the people of the Baltic States from the Soviet Union. Seeing this danger, the Soviet leader Gorbachev came to Vilnius to persuade the Lithuanians to stay within the USSR. The nation refused. On March 11, 1990, the independence of the Republic of Lithuania was officially restored.

On January 13, 1991, Moscow sent to Vilnius its well trained and heavily armed OMON paratrooper units to quell the peaceful quest of the people for freedom. But even under armed attack, the Lithuanian people as well as the Latvians and Estonians responded to aggression peacefully - without use of arms, singing songs of freedom in mass gatherings with an endless and persistent faith in victory. During the military’s crackdown, 13 peacefully protesting civilians were killed in Vilnius. On February 4, 1991, Iceland became the first country to recognise Lithuanian independence. However, only after the old communist coup in Kremlin failed, the Soviet Union recognized the independence of the Baltic states on September 6, 1991, followed by world wide recognition and acceptance of Lithuania as member of the United Nations on September 17, 1991. As the Soviet Union began to disintegrate, Russia agreed to withdraw former Soviet occupation troops from Lithuania's territory in September 1992.

The Baltic Way - Human Chain 600 km Long Linking the

Three Baltic States in Their Drive for Freedom

EU AND NATO MEMBERSHIP

Following its EU and NATO membership in 2004, Lithuania was again reintegrated into the European family of nations. Once an EU member, Lithuania has become an official contributor country giving aid in the quest for freedom to Belarus, Ukraine, Moldova, South Caucasus, Afghanistan and Iraq while also fulfilling its multilateral obligations within the EU and NATO structures.

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - (0) Comment

Gediminas – King of

Lithuania & Russians

Gediminas' Tower (Gedimino pilies bokštas) is the only remaining part of the

Upper Castle in Vilnius. The first fortifications were built of wood by King Gediminas.

Later the first brick castle was completed in 1409 by Vytautas the Great.

Gediminas (1275 - 1341) was the one founding Vilnius as the capital of Lithuania. In works of history Gediminas is referred to as the Grand Duke of Lithuania, but he called himself, and was titled in all official documents, the King of Lithuania, or the King of Lithuania and of Russians. He ruled in the years 1316-1341. Gediminas was lauded as one of the greatest rulers of Lithuania. He established diplomatic and economic links with Europe and invited many artisans and merchants to Lithuania. His reign was marked with tolerance, open-mindedness and fairness. He extended his invitations to all peoples to come and settle in his capital, including Jews and Christians. As a result, many synagogues, temples and yeshivas were built and flourished in Vilnius (for centuries known as "Jerusalem of the North"). During the rule of Gediminas was consolidated authority of the Grand Duke, strengthened the whole system of state institutions, were created conditions for development of agriculture and growth of the cities, expansion of trade and commerce, advance of culture. Gediminas turned Vilnius into a permanent capital of the state and a city of European significance. During the years of his reign Gediminas was the most honoured ruler in Eastern Europe. In his time the aggressions from the West, of European knights, and from the East, of the Golden Horde, were warded off, and many Russian lands were incorporated into Great Duchy of Lithuania.

On receiving a favorable reply from the Holy See, Gediminas issued circular letters, dated 25th of January 1325, to the principal Hansa towns, offering a free access into his domains to men of every order and profession from nobles and knights to tillers of the soil. The immigrants were to choose their own settlements and be governed by their own laws. Priests and monks were also invited to come and build churches at Vilnius and Novogrodek. In October 1323 representatives of the archbishop of Riga, the bishop of Dorpat, the king of Denmark, the Dominican and Franciscan orders, and the Grand Master of the Teutonic Order assembled at Vilnius, when Gediminas confirmed his promises and undertook to be baptized as soon as the papal legates arrived. A compact was then signed at Vilnius, in the name of the whole Christian World, between Gediminas and the delegates, confirming the promised privileges.

But the christianizing of Lithuania was by no means to the liking of the Teutonic Knights, and they used every effort to nullify Gediminas' far-reaching design. This, unfortunately, it was easy to do. Gediminas' chief object was to save Lithuania from destruction at the hands of the Germans. But he was still a pagan reigning over semi-pagan lands; he was equally bound to his pagan kinsmen in Samogitia, to his Orthodox subjects in Belarus, and to his Catholic allies in Masovia. His policy, therefore, was necessarily tentative and ambiguous, and, might very readily be misinterpreted.

Thus his raid upon Dobrzyn, the latest acquisition of the knights on Polish soil, speedily gave them a ready weapon against him. The Prussian bishops, who were devoted to the knights, at a synod at Elbing questioned the authority of Gediminas‘ letters and denounced him as an enemy of the faith; his Orthodox subjects reproached him with leaning towards the Latin heresy; while the pagan Lithuanians accused him of abandoning the ancient gods. Gediminas disentangled himself from his difficulties by repudiating his former promises; by refusing to receive the papal legates who arrived at Riga in September 1323; and by dismissing the Franciscans from his territories. These apparently retrogressive measures simply amounted to a statesmanlike recognition of the fact that the pagan element was still the strongest force in Lithuania, and could not yet be dispensed with in the coming struggle for nationality.

At the same time Gediminas through his ambassadors privately informed the papal legates at Riga that his difficult position, compelled him for a time to postpone his steadfast resolve of being baptized, and the legates showed their confidence in him by forbidding the neighboring states to war against Lithuania for the next four years, besides ratifying the treaty made between Gediminas and the archbishop of Riga. Nevertheless in 1325 the Order, disregarding the censures of the church, resumed the war with Gediminas, who had in the meantime improved his position by an alliance with Wladislaus Lokietek, king of Poland, whose son Casimir now married Gediminas‘ daughter Aldona.

While on his guard against his northern foes, Gediminas from 1316 to 1340 was aggrandizing himself at the expense of the numerous Slavonic principalities in the south and east, whose incessant conflicts with each other wrought the ruin of them all. Here Gediminas‘ triumphal progress was irresistible; but the various stages of it are impossible to follow, the sources of its history being few and conflicting, and the date of every salient event exceedingly doubtful. One of his most important territorial accretions, the principality of Halych-Volynia; was obtained by the marriage of his son Lubart with the daughter of the Galician prince; the other, Kiev, apparently by conquest.

While exploiting Slavic weakness in the wake of the Mongol invasion, Gediminas wisely avoided war with the Golden Horde, a great regional power at the time, while expanding Lithuania's border towards the Black Sea. He also secured an alliance with the nascent grand duchy of Muscovy by marrying his daughter, Anastasia, to the grand duke Simeon. But he was strong enough to counterpoise the influence of Muscovy in northern Russia, and assisted the republic of Pskov, which acknowledged his overlordship, to break away from Great Novgorod.

His internal administration bears all the marks of a wise ruler. He protected the Catholic as well as the Orthodox clergy, encouraging them both to civilize his subjects; he raised the Lithuanian army to the highest state of efficiency then attainable; defended his borders with a chain of strong fortresses; and built numerous towns including Vilnius, the capital (first mentioned ca 1321). At first he moved the capital city to the newly built city of Trakai, but in 1323 re-established a permanent capital in Vilnius, on the site of the capital of King Mindaugas, formerly called Voruta.

Gediminas died in the winter of 1342 of a wound received at the siege of Bayerburg castle. He was married three times, and left seven sons and six daughters. Two of his sons perished in battle. Jaunutis initially ruled Vilnius after the death of his father and was formally Grand Duke of Lithuania until his elder brothers Algirdas and Kęstutis returned from military campaigns in Ruthenia and forced him to abdicate his throne in their favor.

After Gediminas, Vilnius emerged over hundreds of years, expanding, changing, and embodying the creative imagination and experience of many generations of architects and builders from Lithuania and abroad; under the care of generous and perceptive benefactors, it became a city rich in architectural treasures and urban harmony.

Following the craftsmen in other European towns at the end of the 15th century, Vilnius craftsmen began to join together by professions into guilds. Many Catholic churches and monasteries appeared in the town. Stone buildings sprang up inside the Lower Castle. The new Cathedral was among them. Crafts and trade continued to develop in the 16th century. Many beautiful new buildings in the late Gothic and Renaissance style appeared in the town. The most significant event in the cultural life of 16th century Lithuania was the founding of the Vilnius Academy in 1579, which was endowed with the rights and privileges of a university.

Gediminas as depicted in the Sapieha Genealogy in Kodeń, 1709

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - (1) Comment

NEW VIDEOS:

Cold War eyewitnesses

come forward

Eyewitnesses at the Lithuanian Parliament in Janaury 1991.

Photo by Albinas Kentra.

The main objective of the new BALTIC INITIATIVE and NETWORK is to strengthen mutual understanding between the countries around the Baltic Sea through an exchange of information on the Cold War period. The idea is that history should be told from the historically valuable sites at which events took place. Relevant sites include, for example: military installations and towns, prisons and prison camps, partisan bunkers, execution sites, secret police offices, sculptures and architecture or simple squares or buildings where memorable events took place.

While this information is normally handled by museums, they believe that recent history can be told effectively from these sites from the prospective of – it happened here - with the significant help of eye witnesses. Their main task up until now has been to initiate and participate in concrete, international activities and co-operation projects that can improve this mutual understanding. Their main activity thus far has been to support and participate in international cooperation projects that strengthen these activities.

“LISTEN TO THE EYE WITNESSES”

A part of the Baltic Initiative and Network’s sharing of information process is to publish videos based on eyewitness accounts. One special feature of recent history is that many eye witnesses are still alive and can provide important information on the history of events and on valuable historical sites. These are people who were present at the sites as prisoners, partisans, participants in demonstrations, dissidents, military staff etc.

Dear readers, we would like to share with you some of their very informative videos about Lithuania during the Soviet Russian occupation. All of these videos were produced by Algis Kuzmickas of Lithuania in 2011 for the Baltic Initiative and Network.

Jonas Kadzionis - The Partisan in the Forest.

Restored and reconstructed partisan Bunkers, Lithuania.

Jonas Kadzionis was a former partisan, GULAG prisoner and deportee. He has reconstructed the former underground bunker in which he hid throughout his partisan life.

Juozas Aleksiejunas - Prisoner in the KGB prison

The KGB prison

The Museum of Genocide Victims, Aukų gatvė. 2A, Vilnius.

Juozas Aleksiejunas is a former partisan who was arrested by the Soviet occupation forces in 1945. He was interrogated in the KGB prison in Vilnius.

Tomas Sernas - Survivor of the Border Massacre.

The Medininkai Memorial. Lithuania

At 4 o’clock in the morning on July 31, 1991, eight Lithuanian policemen and customs officers were executed in Medininkai, on the Lithuanian border with Belarus. They were killed by shots to the back of the head. The executers were Soviet OMON forces from Riga (Special armed police units). One of the border officers, Tomas Sernas, miraculously survived, albeit disabled. He had been working as a biologist in Kaunas Zoo at the time and felt that he had to do something for his newly independent country so he volunteered as a customs officer.

Vytautis Andziulis - Underground Printer

The secret Printing House. Kaunas, Lithuania

The secret “ab” Printing House was set up in 1979 by Vytautis Andziulis, a professional printer, and Juozas Bacevičius. The printing activities took place in the home of the Andziulis family, north of Kaunas. The printing house produced 138,000 copies of 23 different books, covering Lithuanian history, religion, philosophy and poetry. The printing house was never found by the secret police although there were some close calls.

Albinas Kentra - The camera as a weapon

The Sites of the Freedom Demonstrations. Vilnius. Lithuania

Albinas Kentra was a former partisan, GULAG prisoner and deportee. He is mostly known for his unique video footage of the bloody January events of 1991 in Vilnius when hundreds of thousands of Lithuanian people took to the streets in their newly independent country to protect key institutions from the Soviet military forces.

Gintautas Kazlauskas - Deported twice to Siberia.

Druskininkai Museum of Resistance and Deportations.

Gintautas Kazlauskas was deported to Siberia with his mother and little sister. His sister died because of the hard living conditions. Gintautas and his mother fled back to Lithuania but were arrested and deported once more. Following Lithuania’s independence, he returned to his fatherland after 42 years in exile. He is the founder and current director of and guide at the Druskininkai Museum of Resistance and Deportations.

Irene Spakauskiene - Deported children of the ice

Reconstructed Siberian Yurt. Rumsiskes, Lithuania

Irene Spakauskiene was deported to the Laptev Sea region with her family when she was a little girl. It was a region with permafrost and a temperature of up to minus 50 degrees. The stay was marked by cold, hunger, disease and death, which hit the old and the children first and foremost. The deportees lived in peat huts, so-called yurts. The windows were made of pieces of ice and the inside temperature never rose above freezing.

We would highly recommend you visit their web site http://coldwarsites.net/

It has a wealth of information about not only Lithuania and its Baltic neighbors Estonia and Latvia but also Denmark, Germany, Finland, Iceland, Norway, Poland, Russia and Sweden. This is a very informative site about a very worthwhile project.

Su pagarbe

Vincas Karnila

Associate editor

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - (0) Comment

Timothy Snyder, author of Bloodlands: Europe between Hitler and Stalin:

Perhaps we can find

ways to talk to each other

A rough definition of Snyder's "Bloodlands" (by Timothy Nunan).

By Ellen Cassedy

“Even if all you want to do is understand your own group, you have no choice but to understand the history of others.”

That’s what Timothy Snyder, a professor at Yale University and the author of Bloodlands: Europe between Hitler and Stalin (Basic Books, 2010), had to say at a recent roundtable at the Tolerance Center in Vilnius.

I watched a webcast of the session – and welcomed the opportunity to revisit Snyder’s book, which I’d found challenging on two accounts.

First, immersing myself in the atrocities of the mid-20th century was no easy task. Between 1933 and 1945, in the region Snyder dubs the bloodlands – the Baltics, Belarus, most of Poland, Western Russia, and Ukraine – an unprecedented 16 million people were killed.

Second, Bloodlands required me to consider, simultaneously, the fate not only of my own group, as Snyder puts it, but also the history of others. That wasn’t easy either.

Timothy Snyder

As I watched the webcast, I was reminded of a beautiful summer evening at an outdoor restaurant on Pilies gatve (Castle Street) in Vilnius.

I’d traveled from my home in the U.S. to the land of my forebears in search of answers about my own Jewish family history. I wanted to understand, too, how Lithuania as a country was engaging with its Jewish family history, especially with the Holocaust. My dinner companion was a woman I’ll call Violeta, a friend of a friend, who’d volunteered to help me learn.

We sat down at a checkered tablecloth and ordered a decidedly un-Jewish meal of shrimp salad, then raised our wine glasses.

“L’chaim!” I said, offering the traditional Jewish toast. To life!

“I sveikata!” Violeta responded in Lithuanian. To health!

Growing up in the Soviet period, I asked her, what had she learned about the fate of Lithuania’s Jews during the war?

She furrowed her brow. “We learned in school that many Jews died,” she answered.

“Did you learn about the pits in the forests” – I made a digging motion with my hand – “where the Jews were shot and buried? The mass graves?”

Yes, she said, she had learned about this, too.

She looked away, then met my eyes. “But,” she said, “no one taught us in school how many Lithuanians were sent to Siberia by the Soviet power.”

Her voice grew louder. “Pregnant women and children,” she said heatedly, “they died in Siberia!” I saw that she was glaring at me, with more than a hint of accusation in her eyes.

Now it was my turn to look away. It was hard for me to listen, I found, as Violeta placed the massacre of my people alongside the suffering of hers. It was hard for me to hold in my head the reality of non-Jewish suffering side by side with Jewish suffering.

But if the conversation was not easy, I was glad to be having it.

“Each catastrophe was different,” Snyder said at the Vilnius roundtable. And “we have to accept that our memories are never going to be the same.” But studying the catastrophes that occurred in the bloodlands, and the interactions among those catastrophes, “permits us different ways, from our own different perspectives, to understand.”

If we are truly to understand history, he stressed, we cannot confine ourselves to the study of one people or one nation alone.

Instead, he said, “we have to go to the highest level, starting and ending with human beings.” Then, perhaps, we can “find ways to talk to each other in ways we haven’t before.”

ELLEN CASSEDY

Ellen Cassedy traces her Jewish family roots to Rokiskis and Siauliai. Her new book, We Are Here: Memories of the Lithuanian Holocaust, was published in March and will appear in Lithuanian soon. She lives in Washington, D.C. Visit her website at www.ellencassedy.com.

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

200 years since Napoleon arrived in Lithuania

- Posted by - (0) Comment

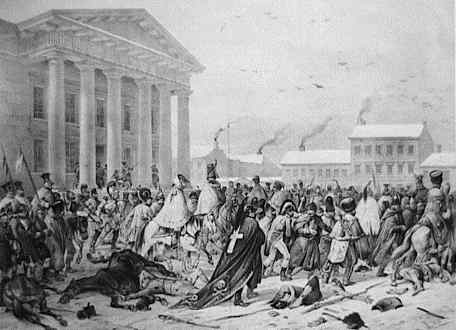

French Army in the Town Hall Square of Vilnius, Lithuania, 1812

By Jonas Damelis (1780—1840), a neoclassicist artist

associated with the School of Art at Vilnius University

By Vytautas J. Šliūpas

Two hundred years ago – on June 24, 1812, the French Grande Armée, led by Emperor Napoleon Boneparte, crossed the Nemunas River near Kaunas and invaded Czar Alexander I's Russia. I will not attempt to delineate the historical facts that are well known, but will present several episodes which deal with Lithuania and Lithuanians. Readers may be interested to know these facts, because Napoleon's first and last steps of the Russian campaign were taken in Lithuania.

War was inevitable

In April of 1812 thousands of orders were dispatched to various corners of the French Empire and Napoleon's Grande Armee was formed. 200.000 men were left in Germany and in the Duchy of Warsaw. The main body , consisting of nine Army Corps – 450,000 soldiers – marched toward the Russian frontier. Among the French, Dutch, Belgian, German, Italian and other not so very loyal mobilized allies (29,000 Prussians and 34,000 Austrians), was a Spanish regiment and 130 battalions of reservists scattered in the vastness of the Empire.

...Ignoring the approaching war, extravagant parties and banquets were held at the Tulleries.

***********

Czar Alexander I was already in Vilnius anticipating Napoleon's attack, which from April 8 was unavoidable. At that date the Russian government sent an ultimatum to the French Emperor demanding withdrawal of his Army from Prussia and other occupied locations east of the Elbe River. The Emperor thus had no other choice but to fight a war.

...In Vilnius, magnificent daily banquets were also in full swing in honor of the Czar. Preparations for war were all but forgotten.

************

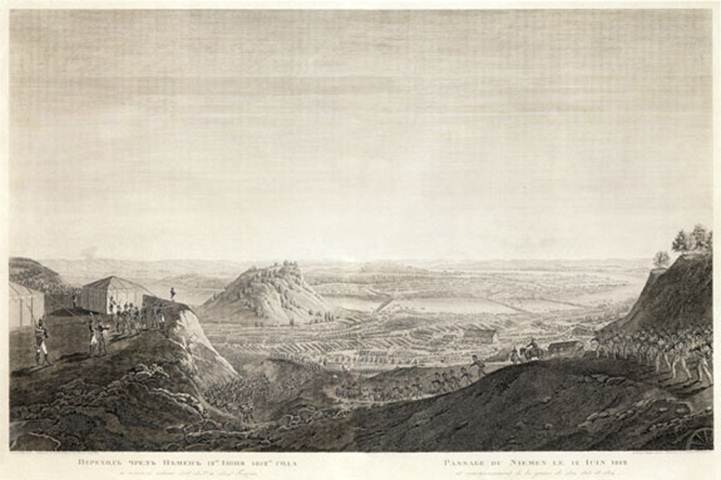

On June 23, the Grande Armee – 400,000 strong and speaking some ten different languages - „a Tower of Babel on the march“ - was preparing to ford the Nemunas River near Kaunas. The river was hidden from view by steep valleys and the Pilviskiai forest. On that day, Major Count Roman Soltys, commander of the Polish cavalry squadron stationed near the Nemunas, noticed a large carriage pulled by six horses galloping towards him. When it halted nearby, Napoleon himself emerged, in deep thought and quite tired after a long journey.

Napoleon's Army Crossing the Nemunas in Kaunas. June 24, 1812

Wood carving. Artist: Dž. Bagetti. Carver: I. Klauberis

The Emperor and his retinue, not wanting to be recognized by the Russian scouts, donned Polish officer's uniforms and walked toward the Nemunas to reconnoiter... That same night, closer to midnight, Napoleon galloped his horse again toward the Nemunas. In the darkness it was difficult to see the other bank of the river. Suddenly his horse reared – frightened by a hare – and the Emperor fell down. Rapidly jumping up he remounted his horse. One of his staff remarked:”This is a very bad omen! A true Roman would withdraw!”

But Napoleon was not one to believe in bad omens...

Next day, June 24, Napoleon was greeted by a marvelous view, all the surrounding hills and valleys were full of troops and horses. When the sun rose and lit the entire moving mass and their shining weapons, an order was given to march. Soldiers, formed in three columns, started toward three bridges, which materialized at night as if by magic...

There was no resistance. The Russians had already retreated.

Suddenly the skies darkened. Thunder and lightning roared like the enemy's artillery. The rain came down in torrents and flooded the entire area. Many horses were lost. Some saw in this violent outburst of nature another bad omen of impending doom.

On the heels of the fleeing Czar Alexander I, Napoleon entered Vilnius on June 28 and remained there for twenty days. Then he resumed his march to Moscow...

The die was cast!

The retreat from Russia started on October 19, 1812 when Napoleon and his Grand Armee, now only 100,000 strong, abandoned the Kremlin. About this exit the Russian commanding general Kutuzov learned only on October 23. However, during the 32 days of Napoleon's stay in Moscow, Kutuzov was able to deploy against him 85,000 infantry, 35,000 cavalry and some 200,000 reservists. Kutuzov had already cut the retreat route near Jaroslavets which was reached by Napoleon on October 24. After a battle at Kaluga, where the French lost some 700 men, Napoleon decided to retreat toward Smolensk. The bitter Russian winter, which started with a snowstorm on November 6, was having its effect on the – even though not yet defeated – French Grande Armee. General Platov's Cossack cavalry was harassing its flanks without respite. When Napoleon reached Smolensk on November 10, his Grande Armee had shrunk to 12,000 men and 40,000 camp followers. In Smolensk they only stayed 4 days. Then on November 25 they reached the Berezina River, where bridges were already blown up by the Russians. The French retreat was cut off! But luck was with Napoleon. Here he met with 20,000 of Marshal Victor's soldiers who were kept behind in reserve.

Napoleon rested on a farm in the mansion of Baron Korsach, the caretaker of the Radvilas family estates.

Napoleon's withdrawal from Russia,

a painting by Adolph Northen.

The Berezina River was half frozen, all bridges had been destroyed. The French troops had to get across it at all costs. They had to find a ford nearby, because at Borisovo, directly across from where they were camping, the Russians had assembled 120,000 soldiers... They had to find that ford very quickly. Time and the Russians were relentlessly pressing without mercy. While the Russian Admiral Chichakov was happy just watching the French movements from across the river, General Wittgenstein could attack Marshal Victor's Corps at any time. Kutuzov itself was in a position to attack Napoleon's rear guard and the left flank of his Grande Armee, or whatever was left of it.

At this crucial moment a real miracle or luck happened for the French. General J. B. Corbineau, finding the river crossing at the Borisovo village blocked by the Russians, led his decimated brigade up the river through overgrown bushes and very dense forest. Suddenly, he came upon a Lithuanian villager, whose horse was wet up to the breast. That meat the villager and his horse had come across, and a ford had to be nearby. The Lithuanian agreed to take the General to a point some five leagues upstream from Borisovo – to the Studyanka village whose log houses were on the river bank just across from the Bychi hamlet. At this location the river divided into several branches dotted with swampy islands, and was flowing between low wooded hills.

Napoleon's crossing of the Berezina

an 1866 painting by January Suchodolski

oil on canvas, National Museum in Poznań

Everyone realized that this was the place one could wade across, as the water reached only to the armpits. General Corbineau and his soldiers jumped without hesitation into the icy water, which drowned and swept away 70 of the men downstream. But the majority of his soldiers reached the right bank. It was proven that a temporary bridge could be built at this location.

Napoleon ordered his engineers to start working on the bridge immediately, while the remainder of his Grande Armee continued to face the Russians at Borisovo.

During the night of November 25, 400 French engineers came to the location and completely naked, standing in the water up to their armpits, started building a wooden trestle bridge. They drove logs into the muddy Berezina ignoring the floating ice sheets all around them. “Some of them” - remembers grenadier Pils - “died on the spot from exposure and were carried downstream frozen into ice blocks. But the tragic end of their comrades did not stop others from their urgent task.”

Across the river one could see the campfires of a Russian Army unit. It was General Chuplitz's division, some 6,000 strong. When the dawn broke, the French were surprised to find that the Russians had abandoned their camp. At a distance they saw30 Russian cannons being towed toward Borisovo. Segur, who saw this with his own eyes, noted: “It required only one cannon shot to destroy this bridge of our salvation, which we had built during the night from river bank to river bank. But the Russian artillery retreated at the moment when we ourselves were just bringing up our own guns into position”.

To the great amazement of the French soldiers, the Russians retreated at the most critical moment,believing that the French were coming over to trap them. They were concentrating all their forces at Borisovo.

The first bridge was completed in the morning of November 26 and 9,300 men of the Oudinot's Corps crossed the Berezina.

Napoleon's life in the hands of a Lithuanian

After suffering great losses but nevertheless successfully crossing the Berezina River, Napoleon divided its forces into several groups, so they all would not be retreating through the same previously depleted areas. The surviving Lithuanian and Polish units were ordered to separate themselves from the Grande Armee at Molodecno. They were to retreat toward Warsaw via Alytus and Gardinas. The cavalry units were to cross the Namunas River at Merkine.

The main French column continued to retreat toward Vilnius. However, because of the continuous extreme winter cold, with temperatures down to -20 degrees below zero, and the collapse of discipline, Napoleon decided to abandon his demoralized troops at Smurgonys. After turning the command to King Murat, on December 5, 1812, Napoleon turned his carriage toward Paris. At first, Napoleon was escorted by his own light cavalry, but after a few leagues he continued his flight alone accompanied only by his trusted Lithuanian aide-de-campe Count Dunin-Vancevičius (Wonsowiczius).

It is known that, right at the start of his flight, Napoleon handed to Count Vancevičius two loaded pistols and ordered to shoot him whenever there was danger of Napoleon falling into the enemy's hands. Napoleons life at the crucial moments of his flight to Paris was entrusted to a Lithuanian officer.

Before Napoleon reached Paris on December 18, 1812, he was overtaken by a military dispatcher from Lithuania telling him some very grim news...

After leaving Vilnius for Kaunas, the French Guards artillery and the surviving Imperial field wagons with boxes of collected loot were unable to negotiate the steep icy slopes of a narrow road at Paneriai. Soldiers threw down their guns, abandoned their cannons, and started emptying the supply wagons. The looting frenzy was so great that the French soldiers failed to notice flying bullets of the encircling Cossack cavalry shooting at them. The rout of what was left of the Grande Armee was complete – the final blow was delivered just outside Vilnius at Paneriai.

From that moment on there was no longer any French artillery left. Marshal Ney, who desperately tried to save the last units of his artillery, rapidly gave up the effort. Marshall Victor was last seen walking on foot toward Kaunas. He was alone because his once loyal soldiers of the rear guard abandoned him.

The last report to Napoleon by Marshal Berthier vividly describes these final hours: “I have to report to Your Imperial Highness, that there is no more any discipline left in the regular army, or in the Guard units, which at this moment consist of 400, perhaps 500 men. Generals and other officers have lost everything they had: many of them have frozen limbs. Many corpses litter the roadways, and houses are full with dying men. At this moment the Army consists of a column only a few leagues long. Receiving no orders, this column starts walking in the morning and stops at night. The Marshals are walking on foot along with all other commoners. The Army has ceased to exist.”

Thus ended Napoleon's dream of conquering the Czarist Russian Empire.

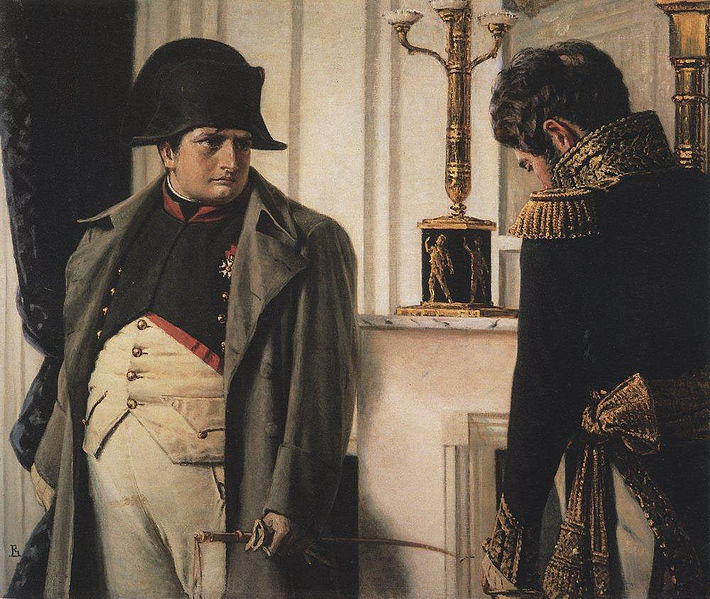

Napoléon and General Lauriston — Peace at all costs!

By Vasily Vereshchagin (1899-1900). Oil on canvas. Historical Museum, Moscow, Russia.

References: Philippe Segur “History of Napoleon's Russian Campaign”, Houghton Mifflin Co., Boston, 1958, presented by Henry L. Gaidys in “Lituanus”, Spring 1984, p. 30-31; Lietuvių Enciklopedija, vol XIX, p.520, Boston, 1959; and Andre Castelot “Napoleon”, The Easton Press, Norwalk, CT, 1991.

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - (0) Comment

Vilnius – the city built

on human bones

Remains of a Grand Armée Soldier buried in Vilnius.

The skull of a Napoleonic soldier, who died during the French army's

1812 retreat from Moscow, discovered on a Vilnius construction site.

Picture: AFP/CNRS/Universite de la Mediterranee/Pascal Adalian

Vilnius, venerable capital of Lithuania, is sometimes called 'the city built on human bones'. It stands in the main Berlin to Moscow corridor, which for over 200 years has been the battlefields of the armies of Napoleon, the Tsars of Russia, Hitler and Stalin, as well as Poles and Prussians - hence its sinister description.

Early in 2002, while bulldozing some ugly Soviet barracks on the outskirts of Vilnius, municipal workers uncovered a mass grave. Thousands of skeletons were discovered there, laid out neatly in layers. Where did these bones come from? Were they those of Jews, massacred by the Nazis? No. For here's a metal button, with '61' stamped on it. Here's another, stamped '29'. And here's a patch of an ancient uniform, once blue. Also to be seen is a gold 20-franc coin from Napoleonic times, and a 'shako' (a French infantryman's helmet), squashed flat.

The drivers of the bulldozers stopped in their work. This was news - archaeological news - and these were the remains of some of the men that Napoleon had led into Russia in his pursuit of world supremacy in 1812.

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - (1) Comment

Antanas Smetona

Lithuania's famous

president who ended

his days in the U.S.

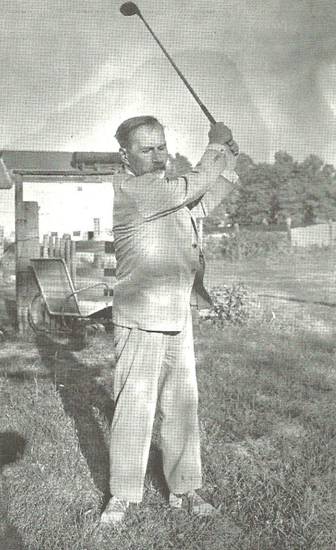

Antanas Smetona golfing in Michigan at the Tabor Farm after he came to the U.S. in 1941, escaping from the Soviet invasion of Lithuania in June 1940 |

||

|

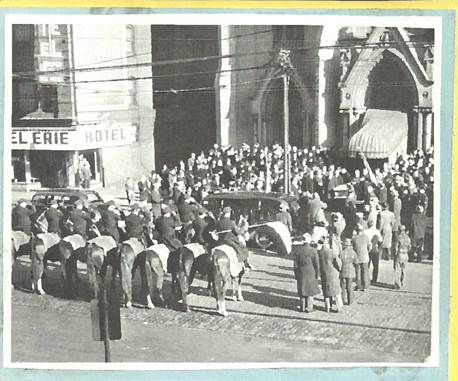

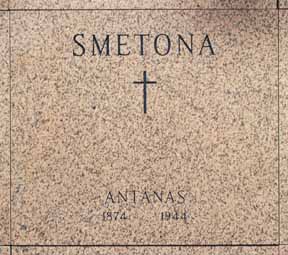

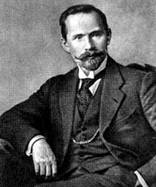

Antanas Smetona (August 10, 1874 – January 9, 1944) was the most important Lithuanian political figure between World War I and World War II. He served as the first President of Lithuania from April 4, 1919 to June 19, 1920. He again served as the last President of the country from December 19, 1926 to June 15, 1940, before its occupation by the Soviet Union. He was also one of the famous ideologists of nationalism in Lithuania.

Lithuania was occupied by Soviet troops in 1940. After the USSR presented an ultimatum to Lithuania in June of that year, Smetona proposed armed resistance against the Soviets. The majority of the government and the commanders of the army did not concur with this proposal, and Smetona turned over the duties of President to Prime Minister Antanas Merkys, and on June 15 he and his family fled to Germany, and then on to Switzerland without surrendering his powers.

In 1941, Smetona emigrated to the United States, and lived in Pittsburgh and Chicago before settling in Cleveland, Ohio in May 1942 with his son Julius' family. While in exile, he began work on a history of Lithuania and on his memoirs. Smetona died in a fire at his son's house in Cleveland, on January 9, 1944, and was buried there. His wife Sofija died in Cleveland, on December 28, 1968, and he also had a daughter, Birutė.

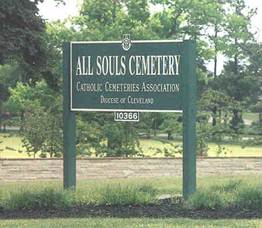

In 1975, his remains were moved from Cleveland's Knollwood Cemetery mausoleum to All Souls Cemetery in Chardon, Ohio.

Early life

Born in the village of Užulėnis, Taujėnai rural district of Ukmergė district municipality, Antanas Smetona was sent to the primary school in Taujėnai. Graduating from the Palanga Pre-Gymnasium in 1893, he passed his entrance examinations into the Samogitian Diocesan Seminary in Kaunas, with thoughts of becoming a Catholic priest, but various circumstances soon thereafter changed these plans, and he enrolled at Jelgava Gymnasium (high school) in Latvia. Here, together with Jonas Jablonskis, Vincas Kudirka and others, he belonged to a secret Lithuanian students' organization. This organization was nationalistic, and anti-Czarist in nature. In the autumn of 1896, he organized the resistance of students against obligatory attendance of the Russian Orthodox Church, and was expelled from the Gymnasium, but was later allowed to study at the Gymnasium No.9, in Saint Petersburg.

After graduating from this Gymnasium in 1897, Smetona entered the Faculty of Law of the University of Saint Petersburg. He joined the activities of the secret Lithuanian Student Organization at the University, and was made its chairman. He became involved with the publishing and dissemination of Lithuanian books. On two occasions he faced the threat of being expelled from the University, and experienced being arrested and a short imprisonment. After his graduation from the University in 1902, he worked at the Agricultural Bank of Vilnius. Two years later he married Sofija Chodakauskaitė.

Early activities

From his very first days in Vilnius, Smetona became involved in the activities of various Lithuanian nationalist groups, and joined the Lithuanian Democratic Party, which he represented in the Great Seimas of Vilnius. He was later elected into its Presidium. In 1904 and 1907, he was on the staff of the Lithuanian newspapers, Vilniaus Žinios (The Vilnius News), and in 1905-1906, edited the weekly Lietuvos Ūkininkas (The Lithuanian Farmer). In 1907, Smetona and the Rev. Juozas Tumas-Vaižgantas established a venture to print the newspaper Viltis (The Hope), and started publishing and circulating it. In Viltis, Smetona advocated national unity; he was also one of the incorporators of the Aušra (Dawn) company for the publishing of Lithuanian books, a member of the Lithuanian Mutual Aid Society of Vilnius, the Lithuanian Learned Society, the Vilniaus aušra (The Dawn of Vilnius), and Rytas (The Morning) education societies, the Rūta Art Society and many other societies, taught the Lithuanian language at Vilnius schools. In 1914, he started publishing Vairas (The Rudder), a new bi-weekly magazine. Also he worked with the writer Liudvikas Jakavicius.

Politics

During the First World War, he was the 1st Vice-Chairman, and later Chairman, of the Central Committee of the Lithuanian Relief Society for helping victims of the war. In the summer of 1916, Antanas Smetona, together with other Lithuanians from Vilnius, presented a memorandum to the German Chief Commander of the Eastern Front, in which he demanded the right of the Lithuanian nation to have an independent State. On September 6, 1917 he started printing the newspaper Lietuvos Aidas (Lithuania's Echo), worked as its publisher and its editor-in-chief. In the first issue of the newspaper, Smetona wrote that the most important goal of the Lithuanian nation was the re-establishment of an independent Lithuanian state.

Between September 18 and 22, 1917, he participated in the Lithuanian Conference in Vilnius, and was elected Chairman (1917–1919), of the Council of Lithuania (later Council of the State). On February 16, 1918, Antanas Smetona signed the Act of Independence of Lithuania.

Smetona

(first right from centre) in the Council of Lithuania, February 16, 1918, the

day Lithuanian declared independence after more than hundred years of Tsarist

occupation.

Between December 1918 and March 1919, he lived primarily in Germany and the Scandinavian countries, soliciting loans for the cause of Lithuanian independence. On April 4, 1919, the State Council of Lithuania elected Smetona the first President of the Republic of Lithuania. On April 19, 1920, the Constituent Assembly elected Aleksandras Stulginskis President. Not re-elected to the Seimas, from 1921 throughout 1924 he edited several periodicals, as Lietuvos balsas ("Voice of the Lithuania"), Lietuviškas balsas ("Lithuanian Voice") and Vairas ("The Steering Wheel").

After the Klaipėda Revolt of January 1923, in the Memelland, which had been separated from Germany, he was made commissioner there on February 20, but due to disagreements with Prime Minister Ernestas Galvanauskas, he resigned from his post.

In November 1923, authorities imprisoned Smetona for several days for publishing an article by Augustinas Voldemaras, in Vairas. Between 1923 and 1927, he was an assistant Professor at the University of Lithuania - at first at the Chair of Art Theory and History and later at the department of Philosophy. He lectured on ethics, antique philosophy, and gave lectures on Lithuanian linguistics. In 1932, he was awarded an honorary Ph.D. at the Vytautas Magnus University.

Smetona participated in the activity of the Lithuanian Riflemen's Union that had staged the Klaipėda Revolt, which gave him greater name-recognition. More than once, he was elected to its central board. Between 1924 and 1940, he was the vice-Chairman of the Board of the International Bank, and one of the members of a number of societies and companies.

Authoritarian president

Antanas Smetona was one of the leaders of the coup d'état of 1926, which deposed President Kazys Grinius, and Smetona once again became President on December 19 of that year (two others briefly held the office during the coup, which began on December 17, before Smetona was formally restored to the Presidency.

See also our VilNews article https://vilnews.com/?p=3545, “The man who declined the Presidency.”

After the coup, Smetona designated Augustinas Voldemaras, as Prime Minister. One year later he suppressed the parliament, and on May 15, 1928, with the approval of the government, he promulgated a new Constitution of the Lithuanian State with more extensive presidential powers. In 1929, he removed Voldemaras and became authoritarian head of state. He was re-elected President in 1931 and 1938, and remained in office until June 15, 1940, when Lithuania was occupied by the Soviet Union.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Why President Smetona's wife smoked Russian cigarettes and refused to talk to Polish ambassador in their native tongue

By: Alfonsas Eidintas / 15min.lt

President Antanas Smetona

and his family: wife Sofija Smetonienė, son Julius, daughter

Marytė

Smetonaitė-Valušienė, and son-in-law Aloyzas Valušis

The following three articles are from VilNews’

collaborative e-publication http://www.15min.lt/en

Alfonsas Eidintas, historian and Lithuania's former ambassador to the USA, Canada, Mexico, Israel, and Norway, has recently published a second book on Lithuania's inter-war president Antanas Smetona. The book is called "Antanas Smetona and His Environment" and the author has kindly agreed to let 15min.lt share some of its chapters. The following is an extract from a chapter on Smetona's wife, Lithuania's first First Lady, Sofija Smetonienė.

Unlike her reserved husband Antanas Smetona, Sofija was talkative and full of energy, partial to good company, a woman of action and resolution. Chodkauskai, a noble family of Antanas Chodkauskas, Sofia's father, who married his cousin Marijona Chodkauskaitė, lived in Gavenonys estate (Šiauliai region) and used Polish among themselves, speaking Lithuanian to peasants only, yet Sofija had sympathized with the Lithuanian national movement from her early days.

Her father would invite Lithuanian students, recommended by the linguist Jonas Jablonskis, to teach his children. During the summer of 1895, a young student from the University of Saint Petersburg, Antanas Smetona, stayed in Chodkauskas' house, teaching his elder son Romanas Lithuanian. Besides Sofija, the family included her sister Jadvyga, their elder brother Romanas and younger Tadas.

Sofija had a talent for learning languages – she picked up German from her German governess that she later improved even more while living in a German boarding school in Mitau, where she graduated from a gymnasium. Sofia's grandmother on her mother's side was a Curonian German, so even her mother spoke better German than Polish.

Sofija, born on 13 January 1885, was 11 years Smetona's junior – which at the time was considered a rather sharp age difference between spouses – and met him, still a student, in Gavenonys.

Young, pretty, lively and talkative 19-year-old, freshly graduated from Mitau Gymnasium, married 30-year-old bank employee Smetona in 1904 and the two moved to Vilnius. It wasn't long before Sofija joined the local Lithuanian society, exhibiting her fairly good voice in choirs and operettas, playing in amateur theater productions, actively participating in charity work. Speaking fluent German, she assisted as interpreter and mediator during the German occupation in World War One.

The Smetona family soon became the centre of Lithuanian cultural life in Vilnius, their home was frequented by the likes of Antanas' university mate J.Tūbelis, reverend V.Mironas, author Kazys Puida with his wife Ona Pleirytė-Puidienė, L.Gira, Mikas and Kipras Petraukas, painter A.Žmuidzinavičius, sometimes even by M.K.Čiurlionis and Petras Klimas. Sofija was a good expert on all the policies of her husband and participated in their making without the slightest sign of ennui (unlike many politicians' spouses who would and still do invest most of their time into updating their wardrobes).

Sofija Smetonienė was reputed as a steadily pleasant hostess who would always invite new acquaintance for a visit at her home. Priest and author M.Vaitkus wrote after a visit at Smetona's in Kaunas: “I found Mrs Sofija at home. Tall, slim. Elongated and slightly dark face. Eyes vaguely Mogul. Slight swelling and shading under the eyes. In general, features quite distinctive and uncommon. One can see a good race. The lady often holds a lit cigarette in between her right-hand fingers which makes them sallow. The cigarette owner, moreover, often touches it with her lips, savors it more fully, leaving marks on lip corners. She received me very simply, almost amiably. We started conversing about routine facts of life, as if we were old acquaintances. By the way, is Mr Smetona home? Yes, she said. And then the lady showed me where to go.”

Vacationing in Palanga in 1925, Antanas Vireliūnas, a known linguist who was very ill at the time, felt his health deteriorating (liver inflammation), his lips and tongue turning black and face yellow. Prof. Iz.Tamošaitis visited the patient, accompanied by S.Smetonienė. She told Tamošaitis, who seemed out of his depth: Vireliūnas would not last long. Indeed, he passed away on 23 July.

Friends talked his family out of transporting the body to cemetery in Kaunas – it was summertime, long distance. They agreed to bury the departed in Palanga. Coffin had to be bought in Klaipėda and brought to Palanga. But how to transport it, by what means, where to get it? While men were discussing it, S.Smetonienė procured a car. All that remained for A.Smetona, reverend Šniukšta, Iz.Tamošaitis, and Parlamentarian Kvieska to do was to say homage speeches in the funeral, silently thanking S.Smetonienė for solving all the practical problems.

Experienced diplomats from the US and Germany were often delighted by her liveliness, ability to quickly find mutual understanding, find their favor, maintain conversations with foreigners. Harry Carlson, American consul in Kaunas 1924-1926, characterized Sofija in one of his wires thus: “Mrs Smetonienė is a highly educated woman of Polish origin, there are indications that her family belongs to Polish nobility. She is exceptionally charming and can be said to be one of the three most important Lithuanian women at the moment. She takes great interest in her husband's politics, although she shows no open interest in any sort of social work, she has not been observed paying any particular attention to education or charity. She is certainly a delightful conversationalist, although her talks always contain certain sharpness and irony when she discusses people and events. Mrs Smetonienė is an ardent gambler and it is well known that she plays rather large sums.”

And here is what Soviet diplomat Sobolevsky though of S.Smetonienė: “Smetonienė is sensible, always in the loop, shows lively interest in everything, well-informed.”

Sofija Smetonienė was ready to sacrifice any prior engagement for the sake of her dearest friends. She instantly accepted an invitation to a dinner party held by US diplomats in the honor of Frederick Coleman, head of the American mission in the Baltic states, but shortly afterwards remembered that, unfortunately, she and the President had already been invited to the USSR embassy (as Smetonienė herself put it, she was invited by the “Bolscheviken”).

However, came 12 October and Smetonienė arrived to the American dinner party, declaring that she had withdrawn her promises to the soviets because she prefered present company, even though she’d got into trouble with the Foreign Ministry for not accompanying the President to the Soviets' event. She recounted how she’d spent half an hour arguing with Prime Minister Voldemaras. She did not leave the party before 1 AM, when the President's adjutant came to fetch her, as usual.

Smetonienė was exceptionally fond of the company of F.Coleman – who would occasionally come to Kaunas on business – because he'd gladly play cards with her.

On 27 October, American Consul Heingartner became witness of the following scene at the President's palace: the guests who arrived for 5 o'clock tea were greeted by the President, descending down the stairs in seemingly good humor. After Smetonienė arrived, everyone drank coffee and started to play a new game (a game of dice called golf), getting instructions on its finer points from one of the guests. Smetonienė had never seen the game, yet she cracked it instantly – faster than any of the gentlemen in the room – and played it with great zest, inviting everyone for another round the following day. “She is a born gambler,” Consul Heingartner noted in his diary.

Upon Sofija's becoming the First Lady again (1926), diplomats noted, somewhat surprised, that the new status made not the slightest change in her attitudes – she remained just as cheerful, honest, frank and slightly mocking of those she did not like. Smetonienė mostly smoked Russian cigarettes. She complained that since her husband became President, he had been smoking too much. He had much on his mind and was smoking to calm his nerves.

On 9 September 1927, an armed uprising erupted in Tauragė and other towns, mostly instigated by the social democrats, but by the evening it got stamped out, culprits arrested. Quite unpleasant for the Smetona family – and on the eve of their daughter Marytė's wedding...

Even though developments of the uprising aupset the family a great deal, they hardly could cancel all the wedding arrangements.

At 7 PM, 10 September 1927, a smart-dressed crowd of Kaunas society and foreign diplomats congregated in the town's Arch-Cathedral. Marytė Smetonaitė was marrying President's adjutant, captain of the hussars Aloyzas Valušis. The Cathedral was full of people from all sections of society, most of them standing as all seats were taken. Sofija Smetonienė led captain Valušis to the altar, the President with Marytė following behind.

Photographers' flashes and buzzing of movie cameras constantly disturbed the ceremony. Archbishop declared the couple husband and wife and read a letter from the Pope. The newlyweds left through the side door while all the diplomats were shaking hands with the President and his wife. Only one foreign diplomat got invited to the wedding ball – the US vice-consul Ch.Gerrity, a personal friend of the Smetona family. Gerrity later told his consul that 75 people attended the wedding, raising champagne glasses on the arrival of the newlyweds to the Pressident's palace.

Each of the newlyweds received a glass of champagne and the young captain threw the emptied glass to the floor – such was the custom here. High clergy and military officers in full-dress uniforms surrounded the tables. After dinner, the bride danced with every one of the guests. Members of Sofija Smetonienė's bridge group sent the young couple an antique silver plate as a present.

***

Both sisters – Sofija and Jadvyga Chodkauskaitė – were true patriots and would always maintain Lithuanian pride. Sofija Smetonienė was wife of President Antanas Smetona and Jadvyga – spouse to Prime Minister Juozas Tūbelis. Both were famous for their passionate patriotism. Poland's envoy in Kaunas Franciszek Charvat has reported that in his meetings with the Smetonas, the President would talk to him in fluent Polish, while his wife Sofija would not use her native tongue and insist on talking to the Pole in French, a language that she spoke rather poorly.

The Smetonas usually spent their vacations in Palanga – upon arrival, the President's family would be greeted by burgomaster Jonas Šliūpas and other distinctive town citizens, after which the President would go to his summerhouse. The Smetonas spent their holidays swimming, sunbathing, and resting. After 1934 – the year of Smetona's 60th anniversary – the family found a new holiday spot, Užugiris Court near the President's home village.

The Smetona family spent their holidays in Užugiris differently than in Palanga – Smetonienė would take care of the house, the President's sister Julija oversee the fields. Cooking was Sofija's responsibility.

One evening, A.Smetona agreed to visit duke Konstantinas Radvila who was one year Smetona's senior and a widower with three grown-up children.

In his youth, the duke had been renown for his great physical strength, his passion for hunting and a collection of over 70 rifles. His residence, Taujėnai manor, was a splendid building, but upon closer look appeared to be rather neglected. After the land reform (1922), the duke was left with merely 80 ha of his formerly gigantic estate, not quite enough to maintain his wide lifestyle.

As the President's car stopped outside the manor, two uniformed footmen came instantly and the duke, attired in beautiful antique clothes, emerged from an antechamber to greet the guest.

This was a symbolic meeting – after all, Smetona's forefathers once slavishly toiled in the fields of the duke's ancestry. His younger sister Taida Radvilaitė escorted them to a tastefully arranged table. As she spoke no Lithuanian, the party communicated mostly in Polish, even though the duke was fluent in Lithuanian, with a slight regional accent.

Duke Konstantinas was a well-educated man, graduate of Riga Polytechnics with a degree in forestry from a German university. After the meal, Radvila conducted Smetona around the manor, showing rooms furnished with Louis XIV furniture, paintings, vases and sculptures, presents and prizes for excellent shooting. The guests were also shown into a glasshouse filled with tropical plants.

When footmen closed the car door and saluted the out-bound President, the duke remained in his manor and prospectless life, while Smetona returned to his wife in Užugiris Court – this is how the family preferred to call their new property, avoiding the more traditional “Užugiris Manor.”

Next week, what were Smetona's attitudes towards Polish national minority and the Vilnius question and why his adversaries would call him "King of Jews."

Lithuanian Poles and Antanas Smetona, “King of Jews“ (I)

By: Alfonsas Eidintas / 15min.lt

President

Smetona is sworn in 1938.

Alfonsas Eidintas, historian and Lithuania's former ambassador to the USA, Canada, Mexico, Israel, and Norway, has recently published a second book on Lithuania's inter-war president Antanas Smetona. The book is called "Antanas Smetona and His Environment" and the author has kindly agreed to let 15min.lt share some of its chapters. The following is an extract from a chapter on Smetona's views on national minorities in inter-war Lithuania.

As people started to build an independent Lithuania, they likewise set out to lithuanianize her. The process of lithuanianization did not escape its excesses – attacks against foreign citizens. It was not only the Holly See delegate A.Zecchini who voiced great indignation in his reports to Vatican, but also President Antanas Smetona, who never approved of attacks against Jews and Poles.

***

In the beginning of 1923, non-Lithuanian signs and plates in Kaunas and across the entire country would get an occasional tarring. People would find notes of proclamation glued to walls of their houses, signed by “patriots” and fascist groups that came to be called “smearers” (murzintojai).

While the smearers' actions were being hotly debated in the press, Augustinas Voldemaras (Prime Minister at the time) denounced the tarring of signs, stressing that “every Lithuanian passing through these tarred signs must lower his eyes in shame” and that it gave the country great dishonor abroad. Gradually, nationalistic attacks against Jews (they were being accused of distrusting the recently-introduced national currency, litas, and of demanding privileges) and the smearers' adventures lost momentum.

In regimes run by one man, the latter's personal attitude to racial and national minorities becomes a significant factor in state politics.

In regimes run by one man, the latter's personal attitude to racial and national minorities becomes a significant factor in state politics; therefore, Smetona's policies in Lithuania say much about him as a person. Authoritarian regimes (and such was Lithuania under Smetona 1926-1940) usually oppress their national minorities, turning a blind eye on their needs. The more radical among Smetona's opponents have repeatedly called him “King of Jews,” thus voicing their discontent with the President's tolerant position regarding Jews, Lithuania's most important and populous national minority at the time. But what about local Poles? What policies did Smetona's regime adopt regarding national minorities?

On March 24, 1936, Smetona gave probably the most comprehensive account of his views on Vilnius question (Lithuania's old capital was at the time under Polish rule, tensing relations between the two neighboring countries) and Lithuanian-Polish relations in a lecture called “The Lithuanian Nation and Its Purpose.” The importance of Vilnius he described thus: “Lithuania without Vilnius is missing one wing in her flight upwards, to the future. It is a moderate position: In want of a third of her land, she cannot have a full plan of her tasks, she does not have the importance in the eyes of her neighbors that she could have. Getting it back would add weight on international plane and internal life would be more spacious, management work would be done more purposefully.”

Poles, according to Smetona, must, too, grant Lithuanians their right to self-determination, must renounce their imperial nationalism, since the Lithuanian-Pole type that once had historical existence, was no longer possible. In the olden days, Poles would call conscious Lithuanians “litvomans,” unfaithfull to the common Polish-Lithuanian cause, but today, when Lithuania was free, they quit doing so, yet still sought to maintain the obsolete origine lituanus, natione polonus type and grant it the right to determine Lithuania's lot.

The late Marshall Pilsudski loved throwing the term around whenever it suited him, like in Paris in 1927, yet this dual national type became shaky with the rise of the Lithuanian nation. Even families would break up because of it: “Professor Ivanauskas of our university, nobleman, Lithuanian from Lyda in origin, had one brother who thought himself Belorussian and another – Polish. A whole lot of our noblemen – Biržiškai, Mongirdai, Landbergiai, Pečkauskaitė, Pšibiliauskienė, Putvinskiai and many more – come from families whose fathers or grandfathers regarded themselves as Lithuanian Poles.

Finally, late Narutavičius from Telšiai, a nobleman of Polish nurturing, was a member of the Council of Lithuania and signed the declaration of independent Lithuania. And his real brother, Narutavičius, champion of Pilsudski, was elected Poland's President. Polonized Lithuanians, who support Poland, would like to see the common folk that are still nationally unconscious to follow their suit; those recalling their Lithuanian origin stand in support of the resurgent Lithuania.”

That is why Poland allegedly cries about how Lithuanians persecute Poles and, in return, persecute Lithuanians of Vilnius. “Do we not have Polish gymnasiums and other Polish schools, founded on our common laws? We do, so the Poles are not being wronged, but they seek to have more rights than is their due, in order to influence the resurgent Lithuanian people. After all, these schools are meant for the polonized Lithuanians, not some newcomers from Poland. We seek national revival of our people, while Poles think it's their right to use them as ethnographic material. We would be happy if Poles allowed Lithuanians of Vilnius region to remain Lithuanians. This is where our views clash. Today, language is the most important mark ofr a nation, but not the only one.”

Smetona specified his views even further in LTS assembly of November 1939, probably in an attempt to curb his own radical supporters from the younger generation: “To persecute foreigners is not only dishonorable, it is unwise. The flood of nationalistic currents will have to go on the ebb. Life will make nations break free of a narrow shell of nationalism, look for contacts in culture instead of differences and return to a universal human basis of morality.”

In November 1939, Lithuania got Vilnius back, but – contrary to what was being said – Smetona was not excited about it for several reasons. Garrisons of the Red Army were stationed there and, besides, by its population Vilnius was – even though quite Jewish – predominantly Polish, with Polish language dominating the city. Old myths – that the denationalized Lithuanians of Vilnius region were waiting for mother Lithuania to come, whereby they'd burst into speaking publicly in their native tongue – appeared to be mere fables, while Poles with resolutely Polish identity met the coming of Lithuanians – the new invaders, as they saw it – to Vilnius with hostility.

Vilnius was a prism to reflect on spiritual capacities of the Lithuanian nation – it was being claimed that the existence of the Lithuanian state depended on national resistivity, yet the question arose – how far should the nationalism go. V.Alantas (Jakševičius) raised a point that nationality should not be considered as something extreme, one should not feared to become nationalist in the true sense of the word. He was critical of Lithuanians' hospitality and welcoming nature, as it was harmful to Lithuania's interests.