THE VOICE OF INTERNATIONAL LITHUANIA

|

VilNews has its own Google archive! Type a word in the above search box to find any article.

You can also follow us on Facebook. We have two different pages. Click to open and join.

|

Historical Lithuania

A sad 70th anniversary

- Posted by - (8) Comment

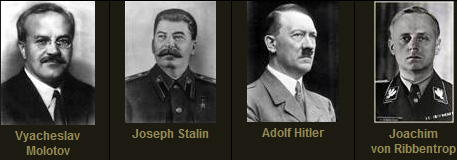

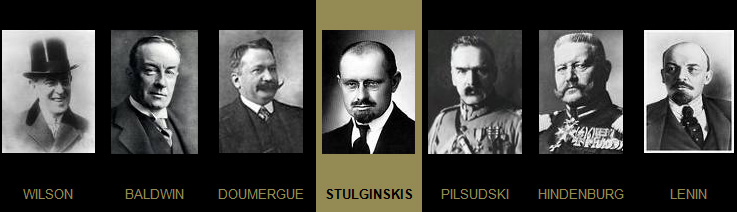

In June 1941, the first massive arrest and deportation of the Lithuanian population was perpetrated. A cargo of 17.500 people were crammed into cattle cars. Moscow’s instruction often required separation of men from their families: some 4.000 men were separated and transported to concentration camps in the Krasnoyarsk territory while 13.500 women, children and elderly people were transported mostly to Kazakhstan, the Altai Mountains territory, Russia’s republic of Komi, the Tomsk region, and the Arctic zone.

As far back as in the first days of the Soviet occupation the searches for "people's enemies" commenced: only in July 12-16, 1940 more than 500 people were arrested - most of them were public men and politicians, army officers, office employees of the independent Lithuania. In the short run, among the dangerous enemies of the Soviet system were reckoned ordinary members of legal parties, organizations that existed in independent Lithuania, police officers, teachers and even Esperantists and philatelists. The repressive departments established pursuing the example of the Soviet Union took into their disposition Lithuanian archives and looked for the "anti-Soviet elements".

At the beginning of the Soviet period, Lithuanian people most of all suffered from deportations - forced mass removal from the domicile to the remote regions of the Soviet Union. The first mass deportation began on June 14, 1941, at night. People realizing nothing were woken up, sat into lorries and conveyed to the nearest railroad station. Thousands of people woken up from sleep (women, children and old people) were told to leave their homes in a hurry. Frightened, not realizing where and why they were taken, most of them failed to take with them even that formally permitted standard of 100 kg of necessities of life. Crammed into the goods wagons, choking from stuffiness without water and hot meal people were kept for several days in obscurity. Only completely formed trains moved to the East - women, old people and children were sent to deportation, the heads of the families - to prisons and camps. Over few days of June, more than 18 thousand people were taken out from Lithuania. This number would have been even larger but the war between Germany and the USSR started on June 22

People deported in 1941 experienced especially difficult fate. Though the war suspended the further deportation, the conditions of the deported became even harder. Upon arrival at the country impoverished by the nationalization and collectivization, allotting the last stock to the front, the deported interested Soviet authorities only as the charge free labour force. Most of the deported were accommodated in joint barracks and dug-outs. People got ill from the epidemics caused by the starvation and anti-sanitary conditions, many of them died, children first of all. In June, 1942, as soon as they began to accustom to their fate, almost half of Lithuanians were taken from Altai territory for real perish to the north of Yakut.

There Lithuanians were distributed to the isle of Tit Ari (at the mouth of the river Lena), Bykov peninsula (at the Laptev Sea), mouth of the river Jana, other places. Debarked from the barges and left in severe polar conditions without lodging, food, warm clothes they died from starvation and diseases. Less than a half of people deported in 1941 returned to Lithuania after 15 or more years. The condition of prisoners and men separated from their families was even more difficult. When the war ended, many of the camps were liquidated, and the prisoners were for hundreds of kilometers driven on foot to other camps. Hundreds of prisoners died on the way and did not reach new places of imprisonment. NKVD camps were enormous cemeteries, in which almost 8 thousand Lithuanians were buried during 1941-1944.

When the Soviet Union occupied Lithuania for the second time in the autumn of 1944, the number of people reckoned among the "anti-Soviet elements" even increased. Not only members of resistance, but also members of their families, partisans' supporters, etc. were reckoned among them. Arrests and deportations of Lithuanian people were renewed.

People were taken to deportation by goods (cattle) wagons with as many people and things stuffed as it were possible. There were no even most necessary sanitary and hygiene conditions in the wagons, while the journey took several weeks or even a month. Sometimes people did not receive food for several days. Babies and elderly people died failing to undergo long and hard journey via the wide expanses of the USSR.

|

|

|

Special agents appointed from Moscow arranged Mass deportations. The lists of the families and individual persons subject to deportation - the main one and reserve (in case the fulfillment of the plan failed) were formed by the district's sections of repressive departments. The inclusion file was made for every deported family or person. The property of the deported family was seized and distributed. The deportations were prepared in advance and with great secrecy in order people would not skulk. |

The local authorities were notified about the prospect deportation only on the eve.

The greatest deportations were masked by very innocent, poetic names - codes used in the correspondence of Soviet departments, radio and telephone conversations. For example, the deportation of May 1948 was named "Vesna" ("Spring"), March 1949 - "Priboj" ("Surf"), October 1951 - "Osen" ("Autumn"). By the amount of the deported people the largest were deportations of May 1948, March, 1949 and October 1951. All of them were fulfilled following the resolutions of the Council of Ministers of the USSR detailed by the puppet Council of Ministers of LSSR and the local MGB.

On May 22-27, 1948 more than 40 thousand people were deported from Lithuania (11 thousand children were among them). On March 25-28, 1949, almost 30 thousand people with more than 8 thousand children among them were deported. During the operation, third by the number of deported people, on October 2-3, 1951, almost 17 thousand people and more than 5 thousand children among them were taken away from Lithuania.

People were deported for various periods of time: for 20 years (in June 1941), for 10 years (1947 - April 1948), for unlimited period of time (in 1949 - 1953). Large penalties menaced for escaping from deportation.

People were deported for various periods of time: for 20 years (in June 1941), for 10 years (1947 - April 1948), for unlimited period of time (in 1949 - 1953). Large penalties menaced for escaping from deportation.

The total number of Lithuanian people deported in 1940-1941, 1945-1952 exceeded 132 thousand. The major part of them was brought to Krasnoyarsk territory, Irkutsk and Tomsk regions

28 thousand from 132 thousand deported people perished from starvation, diseases and unbearable work. About 50 thousand of them could not return to Lithuania for a long time. The last Lithuanians were released from deportation only upon announcement of the order of the Presidium of Supreme Soviet of the USSR, dated January 7, 1960.

|

|

The conditions of Lithuanian people kept in prisons or camps were even more difficult. In 1950, 12 prisons, 8 subunits of concentration camps and 23 inner prisons functioned in Lithuania. It made only small part of the GULAG system. Annually thousands and tens of thousands of prisoners from Lithuania were sent to the prisons and camps scattered in the vast territory of the USSR. The prisoners were transported by stages - from one prison to another or directly to the specified camp. In 1944-1952, more than 142 thousand of Lithuanian people got into the camps of GULAG. As a rule, healthy people several years after getting into the camps became ailing. The death caused by the tortures while interrogating, difficult conditions of imprisonment, continuous starving, hard work was not an exception. In Far Siberia, Kazakhstan, other localities of the USSR, a great deal of graves of Lithuanians were left. By the data of KGB, about 17 thousand people returned to Lithuania from deportation and camps in 1955-1956. |

Lithuanian deportees and prisoners were made a cheap labour force deprived of all rights. People deported to Tomsk region or those who were in Tomsk's camps stung by gnats and blood sucking flies, in winter walking through the deepest snowdrifts, worked in taiga, prepared and floated rafts, gathered resin. In 1942, people deported to the frosty Frigid Zone fished and the rest of them left in the first place of deportation worked in sovkhozs of Altai territory. People exhausted by heat and thirst built roads in Kazakhstan deserts, worked at the cotton plantations of Tajikistan. Many Lithuanian deportees and prisoners worked in Ural Bauxite mines, Kuzbas and Vorkuta coal pits, Bodaib gold mines (Irkutsk region), gigantic sawmills of Igarka. The deportees were paid a little for their work, meanwhile the prisoners worked just for daily food ration which was cut for those who did not succeed to fulfill their quotas.

Source: http://www.travel-lithuania.com

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - (2) Comment

Advent 1945:

|

IN THE WORLD

“Across America, people crowd churches praying with gratitude for the peace in place, and reach out to wounded veterans, children who lost fathers, and neighbors who lost sons. Americans in big cities and small, participate in displays of the intrinsic love so indicative of the American spirit.” |

IN LITHUANIA

In 1944-45 Lithuanians were forced to realize that the bloody World War II had been replaced by a new war, the longest and bloodiest guerrilla war in modern European history, lasting from 1944 to at least 1953. |

Advent and Christmas of 1945 was over most of the world celebrated with a joy and delight almost never before seen. Young and old gathered in homes, on streets and in churches. An endless series of victory ceremonies took place in almost every corner of the world. With a deep sense of joy and gratitude all wanted each other warm, comfortable and relaxing Christmas holidays, knowing that the Nazi era was over and that the world now more than ever could look forward to a future of peace and prosperity. The war had finally released the grip, forgotten was the economic recession of the 1930s. Forgotten was also our Western World’s close friends and neighbours - the Baltic States.

On a small farm in northern Lithuania, in the outskirts of the village Šilagalis, Christmas 1945 is nearing. It is the 22nd of December, and the mother of the house feels very happy that her 21 year old son Povilas has finally come home to visit after having been away for many months.

He has come to change into dry clothes to keep him warm through the cold winter days waiting. His mother is infinitely happy to have her son home this one day, and she does everything she can to treat him with all the good food and drink their little farm can produce. You never know how long it will be till next time.

Povilas had joined a local partisan group earlier in 1945, and now spends all time in the North Lithuanian forests where the local "forest brothers" have established their hideouts. It is from these caches, usually at night, that they conduct their operations against military installations and forces of the Soviet Red Army and NKVD (the secret Soviet police that later changed name to KGB).

The Soviet occupation of Lithuania has lasted for more than a year now, but Povilas and other forest brothers still hope that their constant needle sticks can get Josef Stalin to pull his troops out of Lithuania and the other two Baltic countries.

Povilas is pleased to finally have got a day off, not least is he happy to eat real Christmas food and enjoy some Christmas cheer with the family. A small fly in the ointment is the fact that his father, little sister and little brother are not home.

Both the brother and the sister go to a boarding school in the nearest town, Panevežys, and his father had early in the morning that same day left for the town to bring them home for Christmas. But his mother is here, and when she and he, with arms around each other, go out in the barn to feed the animals, he sings with joy a song he so often has sung in the partisan camp in recent months:

"Dying young is difficult, but not for my country. For my country, Lithuania, I am ready to sacrifice my young life. "

His mother scolds him motherly strictly that he sings: "You know it is not proper to sing now that it's Advent," she says. Lithuania's Roman Catholic Church is strict when it comes to how to behave through the various festive times of the year, and his mother admonishes her son, therefore, while at the same time feeling proud and happy that he makes such an honourable service to the home country.

Back in the farmhouse they suddenly hear that the dog starts to bark. Through the window they see a group of soldiers approaching. The soldiers are still on some distance, so Povilas has time to hide in a small cellar room they have made beneath the living room floor, and the mother has time to cover the cellar hatch as best she can.

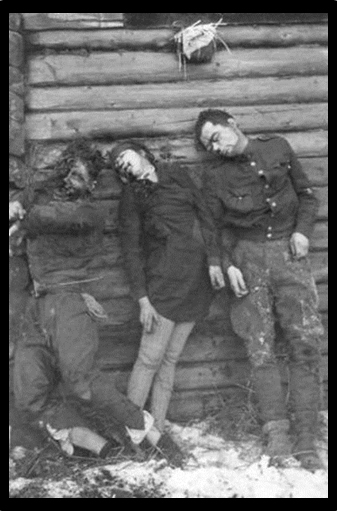

The cellar room has also previously been used to hide partisans, and both think this is a safe hiding place until the soldiers have left again.

The mother walks out into the yard to meet the soldiers from the Soviet Red Army. They ask if her son is home, and if he, in case, is alone. Without waiting for an answer, they storm into the house and begin to turn upside down on furniture and fixtures. Then they start shooting down to the floor to see if it can be cavities under the floorboards. It takes some time before they discover the cellar hatch, but as soon as they find and open it, they fire a machinegun volley into the hole. It does not take long before they pull the now perforated and lifeless body of Povilas out of the basement. The whole operation has taken them five hours, but they have found what they sought. One more young Lithuanian life has been lost in the desperate struggle against the overwhelming odds.

The distance from the farm to the road is over 500 meters, so the soldiers find a chain in the barn so they can tow the corpse of Povilas across the fields over to the military vehicle waiting. The mother is forced to follow, and soon they are on their way to the NKVD headquarters in Panevezys, where the body of Povilas is thrown out in the middle of the courtyard. His mother is brought to a prison cell in the basement.

Early next morning, Christmas Eve 1945, the mother is brutally dragged up from the wooden bench she has laid sleepless on during the night. Today, and every subsequent day for two weeks, she is brought up to ever-new interrogations, walking across the courtyard where the mutilated body of her son still is lying.

Christmas and New Year holiday season in 1945 passes with this terrible routine for a mother in tears and sorrow. Early in January, she is released and can finally go home and tell the family what has happened.

In thousands of homes around the world happy families walk around their Christmas trees. They celebrate that Jesus is born and the world's evil is overcome. 1946 is the beginning of the new and bright times for the human kind…

In northern Lithuania the parents of Povilas and other parents finally find out where the bodies of their killed young partisan sons have been dumped. Under the cover of dark nights in early January 1946, they manage to bring the bodies of their children home to secret burials in their hometown cemeteries.

Christmas 1945 is over. Most of the world looks forward to many good years of peace, freedom and economic growth. The Baltic States' ten-year guerrilla war against the occupiers has just begun.

* * *

The story of Povilas is real. It is based on a passage from the book "Lithuania's struggle for freedom" (Lithuanian Partisans' War Chronicles).

Povilas Peleckas was born on 24 January 1924 into a farming family in the village of Šilagalis in the Panevežys district north in Lithuania. He attended Šilagalis primary school. Later he helped his parents on the farm. In 1944 when the USSR invaded and occupied Lithuania for the second time (first time was in 1940), Povilas was due for conscription into the Red Army. He refused to go. When a local partisan unit was formed, led by Major Januškevičius, Povilas joined the fighters. In September 1945 many of the members of the unit were killed in battle, and another three were killed at the beginning of December. Those who remained alive determined to join a larger partisan unit. But fate was against them.

See also: https://vilnews.com/?p=1739

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

Dates regarding the fall of Soviet communism

- Posted by - (1) Comment

11-13 January 1990 -- one-half of Vilnius’ 600,000 population

demonstrate for pro-independence, to ‘welcome’ visiting

Soviet President Mikhail Gorbachev. Here with the local

communist party leader Algirdas Brazauskas.

By KR Slade

- 1980’s -- economic problems in the USSR; rise of ‘Solidarity’ in Poland

- 1985 -- Soviet President Mikhail Gorbachev announces new Soviet policies of ‘glastnost’ (i.e., ‘political openness’) and ‘perestroika’ (i.e., ‘political and economic restructuring’)

- 3 June 1988 -- in Vilnius, the Lithuanian ‘Sajudis’ (i.e., ‘restructuring’) movement is founded; mostly artists; 17 of the 35 initial members were members of the Communist Party

- 22 October 1988 -- first Sajudis General Congress meets: first organised opposition to the Communist Party

- March-May 1989 -- Sajudis wins legislative seats in the USSR’s highest body of Soviet administration, the Congress of People's Deputies

- February 1989 -- Sąjudis declares Lithuanian ‘independence’, and that Lithuania had been forcibly annexed by the Soviet Union

- May 1989 -- Sajudis proclaims Lithuanian ‘sovereignty’; and declares that Lithuania's incorporation into the Soviet Union was illegal

- 23 August 1989 -- the “Baltic Way”: mass protest of two million people, linking hands in a ‘human chain’, of 650 kilometres: from Vilnius (Lithuania) to Riga (Latvia) to Tallinn (Estonia)

- 9 November 1989 -- ‘fall’ of the Berlin Wall

- December 1989 -- the Communist Party of Lithuania secedes from the Communist Party of the Soviet Union at the 20th Communist Congress

- 11-13 January 1990 -- one-half of Vilnius’ 600,000 population demonstrate for pro-independence, to ‘welcome’ visiting Soviet President Gorbechev

In January 1990, just a few days after the dramatic events

at the 20th Communist Congress, Mikhail Gorbachev came to

Vilnius for a final attempt to convince Brazauskas

to change his mind, but in vain.

- 7 February 1990 -- the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union agrees to give up its monopoly of power; during the next several weeks, the 15 constituent republics of the USSR hold their first competitive elections

- 24 February 1990 -- Sajudis wins 106 of 141 seats in the Lithuanian parliament; the Communist Party of Lithuania wins 23 seats

- 4 March 1990 -- pro-independence Sajudis candidates win an overall majority in the first free elections held in Lithuania since 1940

- 11 March 1990 -- the ‘Supreme Soviet’ (i.e., soon to become the ‘Supreme Council’, which later becomes the parliament) of the Republic of Lithuania unanimously declares the ‘restoration’ of Lithuania’s independence

- 30 March 1990 -- the Estonian Supreme Council declares Soviet power in the Estonian SSR since 1940 to have been illegal, and begins a process to re-establish Estonia as an independent state

- 17 April 1990 -- Moscow imposes economic blockade on Lithuania

- 4 May 1990 -- the Latvian Supreme Council begins the process of restoration of independence of the Latvian SSR, by voting to stipulate a transitional period to complete independence

- 13 January 1991 -- Soviet tanks and troops attempt to storm the parliament and the only television-station broadcasting tower; 14 dead and hundreds injured: all unarmed civilians

- 12 February 1991 -- Iceland is the first country to recognize the new (i.e., re-established) Republic of Lithuania

- 31 July 1991 -- Soviet special agents kill 7 Lithuanian border guards and policemen (at the Lithuania-Belarus border station)

- 21 August 1991 -- failure of the Moscow putsch/coup (since January) to remove Gorbechev

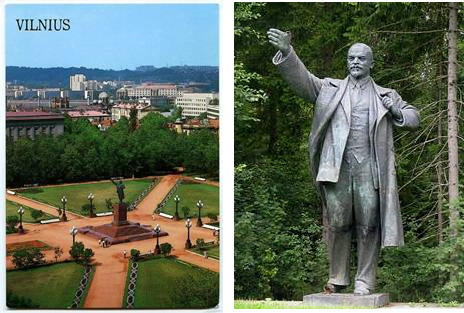

- 21 August 1991 -- Lenin’s statue is removed from the Vilnius square that faces the KGB building

- 29 August 1991 -- Sweden is first western country to open an embassy in Vilnius

- 2 September 1991 -- the United Nations and the USA recognize Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia

- 6 September 1991 -- the USSR recognizes Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia

- 17 September 1991 -- Lithuania joins the United Nations

- 8 December 1991 -- the leaders of the Russian, Ukrainian, and Belarusian republics signed the Belavezha Accords, declaring the Soviet Union dissolved and replacing it with the CIS (i.e., ‘Commonwealth of Independent States’)

- 12 December 1991 -- the Congress of People's Deputies of the Russian SFSR formally ratifies the Belavezha Accords, approving Russia's secession from the USSR, and denounces the 1922 Treaty on the creation of the Soviet Union

- 25 December 1991 -- President Gorbachev resigns as president of the USSR, declaring the office extinct, and ceding all the powers still vested in it to the president of Russia (i.e., Yeltsin); that night, the Soviet flag was lowered for the last time over the Kremlin

- 26 December 1991 -- the Council of Republics of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR recognized the dissolution of the Soviet Union, and dissolved itself

- 31 December 1991 -- all official Soviet institutions cease operations

- 31 August 1993 -- the last Russian soldier leaves Lithuania

- March 2004 -- Lithuania joins NATO

- May 2004 -- Lithuania becomes a member of the European Union

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - (5) Comment

Remembering

Darius and Girenas

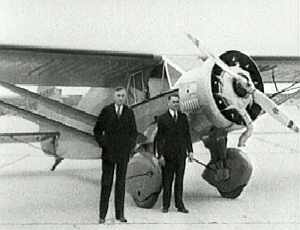

The American-Lithuanian pilots, Steponas Darius (1896-1933) and Stasys Girenas (1893-1933) attempted in the year 1933 to beat Charles Lindberg’s non-stop distance record across the Atlantic by flying from New York City to Kaunas, then the temporary capital of Lithuania.

Their plane, Lituanica, was an Bellanca CH-300 Pacemaker airplane. After successfully flying 6,411 km, it crashed, 650 km from its destination, Kaunas. Both pilots were killed.

Movie clip from the crash scene.

Steponas Darius was born at Rubiske, Lithuania in 1896 as Steponas Darasius. His father died while he was young; his mother remarried and the family moved to America in 1907. The family eventually settled in Bridgeport, a Lithuanian neighborhood in Chicago. While growing up, Steponas became quite the sportsman and played a variety of sports, including rugby, football, basketball, baseball, and boxing. In addition, he worked as an errand boy at an aviation store owned by famous aviation pioneer Wright brothers.

During World War I he shortened his surname to Darius, and joined the U.S. Army in 1917. He served valiantly in France and was awarded the “Purple Heart” and the “Great War for Civilization” medals. After returning to Chicago briefly after the War, Darius returned to his homeland Lithuania in 1920, which was fighting for its independence. He joined the Kaunas Military School and was promoted to the rank of lieutenant upon his graduation in 1921. He joined the training squadron of the Lithuaian Air Force in 1922, and participated in the 1923 liberation of Lithuania’s port city of Klaipeda. He served in the Lithuanian Air Force for 5 years, and was promoted to the ranks of flying officer, and flight lieutenant.

Having received a year’s leave from the Lithuanian army Darius left Lithuania in 1927 and returned to the United States to visit his friends and relatives there. On his journey home he witnessed the triumphant celebration for aviator Charles Lindbergh at Le Bourget Airport in Paris. Darius was inspired and determined that he would someday fly a plane from New York to Kaunas.

Upon his return to the United States, Darius earned various pilot’s licenses, including international and transport pilot. He began racing airplanes and also established an aviation company with an American pilot in Indiana. After some mechanical misfortunes, Darius left the firm in 1929 and returned to the Chicago area. He then began working for a Bellanca dealer at Palwaukee Airport north of Chicago. While there he became a pilot and instructor of Commercial aviation, and a master at flying all types of aircraft of his day.

The pilots and their aircraft, Lituanica.

Steponas Darius teamed up with aviator Stasys Girenas in 1932, and the pair formed a flying partnership dedicated to a well-publicized trans-Atlantic flight. Girenas also had a similar background as his partner, having been born in Lithuania, educated in Chicago, and serving in the U.S. Army in World War I. The duo purchased a used Bellanca Pacemaker plane from the Chicago Daily News in 1932, dubbed it the “Lituanica” and modified it for their flight. Money was raised from numerous Lithuanian clubs and organizations to finance their operation.

The duo left Floyd Bennett Airport in New York City headed for Kaunas on July 15, 1933, and crashed over Soldin, Germany (115 km. north of Berlin) on July 17 after 35 hours in flight. It was strongly suspected that they were shot down by the Nazi’s after they strayed well into German airspace. A thorough investigation however, pointed to stormy, rainy weather and fog as the most likely deadly factor in their flight. Autopsies revealed no signs of any bullets on their bodies whatsoever. The bodies of the pilots and their plane were taken to Kaunas, and over 60,000 persons attended the funeral there. The duo have since been memorialized on numerous Lithuanian stamps, coins, medals, and decorations. Numerous monuments have been erected in their memory both in the United States and in Lithuania.

When Lithuania regained its independence in 1990, plans were made for the reestablishment of the national monetary system, the litas. A design competition was held for the various denominations. The 10 litù banknote was designed in 1991 by 28-year-old artist Giedrius Jonaitis (born 1963), a graduate of the Vilnius Art Academy, and a member of the Lithuanian Artists Association. The note’s design features the theme of Darius and Girìnas. The images of the flyers were based upon official 1933 press photographs of the duo. The back of the note features their plane flying over the waves of the Atlantic, with an outline of North America and Europe in the background. No boundaries of countries were drawn on the map portion, to avoid any controversies that existed as the result of the occupation of the capital city of Vilnius by Poland from 1920 to 1939, and subsequent Soviet-imposed boundaries following World War II.

10 litu note showing face side

In 1934 Steponas Darius and Stasys Girėnas bodies were embalmed by professor Jurgis Zilinskas. In 1936 the Lithuanian government decided to build a mausoleum for them in Kaunas' old cemetery, that was destroyed after Soviet re-occupation. From then until the present day, the wreckage of Lituanica has been on display in the Vytautas the Great War Museum in Kaunas. At present the pilots' bodies rest in the Military Cemetery of Šančiai, Kaunas.

Pašto ženklas, 75th anniversary of

S. Darius and S. Girenas flight.

Chicago's Lithuanian community erected an Art Deco Monument commemorating the pilots in Chicago's Marquette Park in 1935 where it still stands to this day.

Feliksas Vaitkus flight was inspired by the flight and commemorated it with a flight of Lituanica II in 1935.

The flight is commemorated in a movie Skrydis per Atlantą (Flight over Atlantics - 1983). Kaunas's sports stadium, S.Darius and S.Girėnas Stadium where the Lithuanian national soccer team plays its home matches is also named in their honor. There is a tall stone monument near the stadium, the Lithuanian Academy of Sport and the Ąžuolynas Park dedicated to the pilots.

Sculptor Bronius Pundzius has made a relief of the pilots' faces on the Puntukas, then the largest known boulder in the territory of Lithuania in 1943.

Relief at the Puntukas boulder, 1943.

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - (1) Comment

Dénes Fejér |

Ruszkik, haza!

|

Text: Aage Myhre

aage.myhre@VilNews.com

“The Szeged initiative could be seen as the first crack on a dam where water is about to pour through. Of course, you don’t immediately realise when you see a small stream of water; that what follows it is going to overwhelm you. The Communist leadership did not see right away what actually was about to happen, as they did not expect such a massive force appearing in just a few days.”

Dénes Fejér, who was 23 when the revolt started, stands here in the Aula that looks more or less the same as it did in 1956, demonstrating how things started evolving exactly here that October evening 55 years ago.

Hungarians gather around the head of the toppled Stalin Monument in Budapest 1956.

I ask Dénes Fejér to explain more about the 1956 revolt that started here in Szeged:

You were yourself present in that Aula meeting, and if I understand you correctly, this meeting became a fateful event (among several other developments in those days) which led inevitably to the outbreak of the revolution. It was the first meeting after World War II where questions were not pre-arranged slogans glorifying the regime, but where - because of the insistence of the audience - everyone was allowed to speak, and raise questions. What would you say were the most significant things happened at that assembly?

For two years after the end of the war in 1945, there was a plural political system in Hungary. Different political parties existed, and in the 1945 general elections the Independent Smallholder and Civil Party received absolute majority with 54% of the votes and the Communist Party only received 17%. Stalin realised that the people of Hungary did not want to embrace its system. The 1947 elections were already fraudulent and the Communist forces won. In 1948 the Social democratic Party was forcibly incorporated into the Communist party. The general wave of terror appeared only after this time. Forced nationalisation was started with businesses, commercial institutions, industrial entities and later, even private property like houses. A terror organisation was created within the Internal Ministry, called the AVO (State Security Authority) which later became an independent entity, having its own rules and methods.

This was the background where the MEFESZ was established, as the very first independent organisation in Communist Hungary. The programme and its demands were summarised in twenty points of the there are a few that are interesting. These included the request for open and free debates, the open trial of guilty Communist functionaries, the abolishment of death penalty in political cases, democratic elections, freedom of speech, and the that the 15th of March, the Commemoration Day of the 1848 Revolution should become an official national day. As you can see, these conditions and demands are natural in a free country but were unknown and unthinkable in a dictatorship. Although not part of the twenty points, another demand was phrased by the participant of the meeting. This was later a key phrase of the revolution: Russians, go home! The most fundamental demand was for the truth, that is to say that the leaders of the country should not lie and should not make the young people and the population lie. Telling the truth in Hungary at that time meant sever prison sentences.

To my knowledge, the assembly started as a rather innocent gathering where the students simply asked: “Why are the Soviet troops still stationed in our country?”, but ended with a the clear demand: “Ruszkik, haza!” - “Russians, go home!” From such a radical manifestation of the demands, you must have known that this was about to become dangerous?

The whole meeting started as a regular Communist youth organisation meeting. The Communist youth leaders gathered before it and reviewed the demands of the MEFESZ leaders, like András Lejtényi. When they learn the radical nature of these, they became frightened and left immediately for higher authority, the Communist party representatives at the university. Then the MEFESZ leaders went to meet the gathered students, read their demands, and the MEFESZ had the day!

“There was a general feeling of freedom among the participants. Fear disappeared. Saying the truth was a standard, normal thing during the event that caused happiness and joy among the audience.”

Didn‘t you realise that, according the Soviet system of those days, your collective name was "Shut up!" Did you not know that the Aula microphones were only for the Party collaborators and that nobody else were supposed to talk?

Nobody thought of ‘Shut up!’ at that time. After the first few words, there was a general feeling of freedom among the participants. Fear disappeared. Saying the truth was a standard, normal thing during the event that caused happiness and joy among the audience. The principle of ‘Shut up!’ had accumulated an amount of pressure in everyone that just erupted then. The age of ‘sober thoughts’ ended and the demand of freedom and truth became prevalent for the university youth.

You were yourself working as a journalist those days, and on the 23rd of October the newspaper “Delmagyarorszag” published your article called “Az igazsag keresesenek utjan”. What was the essence of this article and what reactions did you get?

This article, titled the ways of finding the truth, summarised what I have just explained above. It is very typical that we were not even sure whether the article would appear at all. The official, Communist newspaper Délmagyarország reported the event but left out the most important aspect which was the break of the dam, the shedding of the Communist oppression!

The period of hope to win over the mighty Soviet Union by peaceful measures, however, did not last long, and soon fights started spreading all over Hungary and the revolution began before your eyes. How will you describe this outcome of your efforts from the Aula assembly?

The main fighting happened in Budapest. This was the obvious and visible sign of the revolution. The fighting, the combat on the streets. The AVO, the armed troops and the Soviet soldiers were all surprised that ‘here they shoot back’. It was believed that a demonstration of force with tanks on the street would frighten people and prevent the escalation of the events, thus helping the consolidation of the Communist dictatorship. It didn’t happen like that.

Probably the Hungarian national character contributed to this as well. The courage to start again, to love one’s country, the national tradition of not giving in to slavery.

The revolutionaries of Budapest used bottles filled with petrol against tanks. They had no heavy weapons or anti-tank artillery. They fixed a burning piece of rag on the bottle and tossed it to the moving vehicle. The burning liquid turned the steel monsters into burning coffins. When the Soviet soldiers were abandoning their vehicles, they became easy preys to the weapons of the fighters.

There was an interrelation between the demands of the Szeged students, the fighting in Budapest and the revolutionary state nation-wise. The mental preparation rallied the fighters. The machine guns and the words were equally weapons of the revolution. Words changed things without bloodshed. From the smallest villages in Hungary to any institution or organisation, everyone of them had revolutionary councils. They replaced the very often incompetent previous leadership whose only added value to the system was their loyalty to the oppressing regime. The highest authority in the Communist state, the Central Committee and the Political Committee was simply dismissed. Instead of them reliable and trustworthy people were elected by the population or members of institutions or organisations. With open or secrets ballots. I was elected by a secret ballot to be on the workers’ council of the press in Szeged, and on the city’s revolutionary council.

I think this was the real result of the revolution. Replacing the old, Soviet puppets, the Communist leadership, and raising new, honest people into the power. This was created by the synergy of the students’ wishes and of the fighting in Budapest.

“For those who have never lived in oppression, in fear and in deprivation, for those who, on a daily basis, enjoy freedom and the rights of liberty, they probably don’t really know what freedom means for a prisoner.”

It has been said that something nearly supernatural stirred the hearts, minds and consciousness of the Hungarian people those days. Those shared feelings with friends and strangers must have been very special?

This special, disturbing experience is not difficult to describe for those who lived through it. The beautiful memories must be recalled from the past half-century. For those who have never lived in oppression, in fear and in deprivation, for those who, on a daily basis, enjoy freedom and the rights of liberty, they probably don’t really know what freedom means for a prisoner. I believe that it was this everlasting desire for freedom that prevailed back then. It was as if we were not even walking on the face of the Earth, as if floating in air. The communication changed among people, they were smiling to each other. They were nice, understanding towards each other. We even believed that the ‘guards’, our oppressors could change because they would realise that it is, in fact, better to live like this, free. It is probably also true that the experience of freedom created delusions.

By mid November 1956, it became evident that your revolution was lost. Not only the street fights, but also the lengthy demands of the students, which were fully supported by the whole society, were not going to be met. Instead, more and more of reprisals and arrests happened and an air of bitter disillusionment began to replace the heady days of the victorious revolution. How would you describe these days?

In the first days of November, it became obvious that the revolution had failed. Not in its results, not in its memories, not in its principles but in its survival. It was not our weakness but the overwhelming Soviet military power that defeated it. The twelve days a freedom turned into a totally different direction. In a few days we suddenly had to realise that those who had pretended to be with us till the 4th of November in 1956, turned into bloodthirsty puppets of the occupying forces and lost their human faces, becoming willing executioners.

The new puppet regime with Soviet arms behind it could only gradually strengthen its own position. They were expecting results, agreements, and waiting for their supporters t show once again. This started very slowly with the dismissed Communist leaders and members appearing again and again. Once they were feeling safe, the brutal punishment started.

We were hoping that they might have learnt their lesson, that we could not be treated the same way as we had been treated for nine years before the revolution. This was not the case, they continued everything in much the same way as it had been before. Everything came back, the deportation camps, the beatings, the prisons, the torture. Hungary again became a prison and we again humiliated prisoners.

It took some time before the Soviet rulers of your country were able to close the borders completely, and Austria was very willingly letting thousands of refugees cross into their country. You decided not to leave, why was that?

It became obvious that for those who had participated in the revolution, there was no place in Hungary any more. And many of them indeed left the country. Maybe some left because of fear, some because of adventure or new possibilities. Almost 200.000 people left the country. One of my best friend left who is currently living in New York while I was kept in a Soviet military prison in Eastern Hungary. Another friend of mine, who was briefly arrested with me, was inviting me to go to France.

It had never occurred to me that I could or would leave. Never, for a moment. I knew that I had account for all my activities eventually, and I was hoping that my life would be spared. During the revolution I did not fight, did not kill anyone. In my captivity Major Zokov, the Russian officer was interrogating me about all these things. Ha was trying to convince me that we were counter-revolutionaries while I was trying to convince him that we were revolutionaries. We couldn’t convince each other of course. I do not recall any fear gripping me, when, together with seven of my colleagues, I was transported in an ambulance, escorted by two armed armoured personnel carriers. I was wearing a white shirt and, when we were disembarked at the main square of Csongrád to be taken to the nearby hills, I remember thinking that anyone could easily recognise the white on a corpse, and might be able to inform my mother about my fate. I was not executed, but taken to Debrecen to the Soviet military airfield.

After I was released from prison, I did not want to leave. I couldn’t leave my country. I would not replace Hungary for any other place. I have seen a few peaceful spots in the world where life could be different than here. Once a Hungarian poet has said that for a Hungarian patriot ‘whether your faith may be blessed or cursed, here [ie. in Hungary] you must either live or die’. This is a moral command for me.

Some of your fellow students were executed and the Soviet jails were filling up during the next few months. You were among them arrested, hence it would be interesting to hear your personal story from the time after the revolution was so brutally crushed?

In the spring of 1957 I was arrested again, this time by the Hungarian political police. But before that an interesting episode happened in my life. When I was released from the Soviet prison, in February I returned to Szeged where I was approached by the newly organising Communist party, through two veteran leaders, Vince Bite and Károly Csíszár. I used to know Uncle Vince, since when I was ten to twelve, I used to be his helper in playing bowling at the beach. They told me to become member of the MSZMP [the newly formed Communist party] because I had been selected to be chief editor of the Délmagyarország newspaper. I had three days to consider their offer. I turned it down. Have you given it enough thoughts? Uncle Vince asked me. I have, I told him. Well, I hope you won’t regret it, he answered.

In two months time, I was arrested. I was interned. The whole thing became only a little bit clearer when I was released after one year. The temporary imprisonment that required no court verdict, could be prolonged indefinitely after every six months. When I was released, I was only allowed to do manual labour, only as a non-qualified worker, despite having a university degree with a certificate that allowed me to teach. My driving license was withdrawn, my reserve officer rank of the army was taken away, I did not get a passport, and could not travel abroad. As I recall, it did not really effect me because after finishing secondary school, I went to work on the Tisza bridge and learnt the craftsmanship of carpenters. This enabled me to work with my own two hands, and solved my financial problems.

What was difficult was the social exclusion. When my friends saw me on the streets, they went to the other side. Nobody dared speaking to me, or to be seen in the company of a convicted ‘counter revolutionary’. I was living with my mother and with my elder sister because I had lost my elder brother who had died in Russian captivity in the war.

During the sixties the terror had waned a little bit. I was allowed to teach in elementary school, although only subjects that were practical based, handcrafts. On regular basis a political officer appeared to check on me, and to try to make me work with them as an agent. I refused, and eventually got fed up with it all, and I returned to the construction industry. In the end I became a foreman, then a project manager. I was applying for eight years to the Szeged university law faculty but was always turned down. In the late 80s I was invited to be as chief editor of one of the first independent publishers. This was already the end of the Kádár-regime [János Kádár was the leader of Communist Hungary after 1956, till 1989. The period between 1956 and 1989 was often referred as the Kádár-regime.]

“It was only after many years that we learnt that the USA and the Great Britain informed the USSR that they would not oppose their intervention in Hungary.”

The governments of the free world watched your Hungarian Revolution with deep admiration even if none of them seriously considered providing military support, nor condemnation strong enough to stop the brutal actions of the Soviet Union. How do you view the behaviours of the Western countries those days?

The Western world provided enormous help to those almost 200.000 Hungarians who left the country. Those who went not as adventurers were appreciated by their new countries. Among the refugees you can find people who still come back to Hungary and who in fact, have two countries now. They have no roots, and their children have departed from Hungary for good.

The Western influence that we had in the days of the revolution was deceiving. It was only after many years that we learnt that the USA and the Great Britain informed the USSR that they would not oppose their intervention in Hungary.

Radio Free Europe was continuously encouraging the fighters to carry on because they were promised foreign help. This has led me to conclude that if it succeeds, if we had national local government in Szeged, I would suggest to change the name of Roosevelt Square in Szeged (like it was changed from Stalin Square) as I cannot support a liar, a friend of Soviets, even if he had been once the President of the USA.

Roosevelt Square in Szeged. The inscription lauds Franklin for his stand against

Fascism. Dénes Fejér, however, wants to change the name of the square.

“I cannot support a liar, a friend of the Soviets, even if he had been once

President of the USA,” he tells me.

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

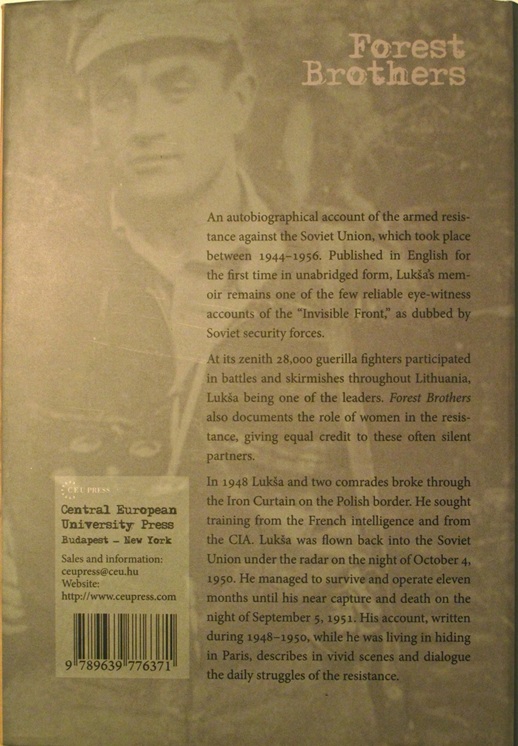

Back cover of Laima Vince’s book

“Forest Brothers: The Account Of An Anti-Soviet Freedom Fighter - Juozas Lukša.”

I have travelled in several former Warsaw Pact countries. In Hungary I met a person who participated in their 1956 uproar. In Slovakia and the Czech Republic I talked to people about their ‘Prague Spring’ of 1968. The people I talked to were rightfully proud of the uproars their countries performed against the mighty USSR, but when I asked them about the revolts that took place here in Lithuania and the other two Baltic states during the period of 1944-53, they all lacked concrete answers and knowledge. “We simply didn’t know,” they told me...

And they are not alone. I believe very few in the entire world have ever heard about the guerrilla war that took place here in the very centre of Europe after World War II, even if the number of victims in fact can be compared to the Vietnam War (1960-75).

It has been estimated that the losses of the Lithuanian partisan war’ amounted to 70,000 Soviet soldiers and 22,000 Lithuanian ‘Forest Brothers’, making this war one of the longest and bloodiest guerrilla wars in the history of the world.

For comparison, the United States lost 58,000 soldiers in Vietnam.

The outcome of this uneven war became an extremely sad and gruesome chapter in Lithuania’s history. Some 132,000 individuals were captured and deported to the Arctic areas of Siberia, 70% of them children and women, and more than 50,000 of these fine people died under the extremely harsh conditions up north, never able to return to their homeland alive.

During the same period, another 200,000 people were thrown into prisons. Over 150,000 of them were sent to the Gulags, the USSR’s concentration camps. These mass deportations continued until the death of Josef Stalin in 1953, but many prisoners remained in the camps also during the time of Nikita Khrushchev.

In a book by Anatol Marchenko published in Germany in 1973, he tells about his experiences from Soviet prisons and concentration camps in the early 1960s. One of his stories is about three Lithuanian prisoners who tried to escape from the convoy in a forest. Two of them were quickly caught, then shot many times in the legs, then ordered to get up which they could not do, then kicked and trampled by guards, then bitten and torn up by police dogs and only then stabbed to death with bayonets. All this with witty remarks by the officer, of the kind; "Now, free Lithuania, crawl, you'll get your independence straight off!"

This is one of thousand stories you can read in many now available books about the Soviet horrors. From 1917 to 1991, politics in the USSR started and finished with the Communist Party; it was the only game in town.

What passed for elections were a contest between members of the same political party - no candidates other than communists were allowed to run. The people who ruled the country were dictators; some more brutal than others. The Communist Party owned everything - land, factories, housing, and farms. The masses went about their daily lives under the direction of the Party. They were told where to live, where to work, and where to travel. There was very little freedom of choice in anything. The ideal behind this system was that everyone lived and worked for the good of the community.

But, the power of the Soviet Union, under the domination of Russia, was built on sand not rock. Under communism, individuals learned to lie back and do nothing and the idea of everything being owned by the community instead of individuals meant that nobody felt responsible for upkeep and maintenance; or as it is expressed in a Spanish proverb: "The cow of many is well milked and badly fed."

But even if there existed both humor and good days for people during those years, the extreme sufferings the USSR meant for this part of Europe should never be forgotten, and the Lithuanian partisan war is certainly one of the most important stories to tell our posterities along with the stories about Czechoslovakia in 1968 and Hungary in 1956.

I suggest you to read the books of Laima Vince (Forest Brothers: The Account Of An Anti-Soviet Freedom Fighter -Juozas Lukša), Ruta Sepetys (Between shades of gray) and Antanas Sileika (Underground).

Have a look at their web pages:

LAIMA VINCE – http://www.laimavince.com/forestbrothers.html

RUTA SEPETYS – http://www.betweenshadesofgray.com/

ANTANAS SILEIKA – http://antanassileika.ca/

Aage Myhre,

Editor-in-Chief

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - (1) Comment

Chronicle of Lithuania

in a global perspective

Lithuania is a country that cannot be understood if you don’t know at least

something about its exceptional past and its extraordinary global ties – with

Italy, India, South Africa, Israel, Poland, Belarus, Ukraine, Crimea/Turkey,

Sweden, Germany, Russia, Australia and America

LITHUANIA - IN A GLOBAL PERSPECTIVE

A Chronicle of historic and contemporary Lithuania and her relations to the world

See also: https://vilnews.com/?p=886

I have, over the years since I first came to Lithuania from my native Norway in 1990, often wondered why authorities or other institutions here haven’t published a chronicle describing the many ties and touching points this amazing country has to the rest of the world throughout historical and modern times.

Because Lithuania is a country that cannot be understood if you don’t know at least something about its exceptional past and its extraordinary ties with Italy, India, South Africa, Israel, Poland, Belarus, Ukraine, Crimea/Turkey, Sweden, Germany, Russia, Australia and America.

This was why I some years ago put together my own electronic ‘Chronicle of Lithuania in a global perspective’. that I often have used for presentations to guests and others with some interest in this little country that once was a ‘superpower’ of world class and for hundreds of years a thriving cradle for co-existence between people from many nations, cultures and religions. Or, as the British historian Norman Davies puts it: “Lithuania was a haven of tolerance”. Davies was not the only one who took notice of this. Erasmus of Rotterdam (1466 – 1536) is quoted as stating; “I congratulate this nation [Lithuania] which now, in sciences, jurisprudence, morals, and religion, and in all that separates us from barbarism, is so flourishing that it can rival the first and most glorious of nations.”

I know that foreign embassies and international companies, as well as many individuals, for many years have been using my ‘chronicle’ when they try to describe Lithuania to people and institutions in other countries, and I also urge you, dear readers, to pass on a link to this 'chronicle' to all your friends and acquaintances. That’s how we together can make Lithuania better known and understood for people around the globe...

Please keep in mind, however, that this is my personal collection of articles and impressions, not in chronological order, hence it might very well be that a historian would have chosen other articles and put together the information in a completely different manner. Nevertheless; have a good read. I believe afterwards you will agree with me that Lithuania is a truly amazing and far too little known spot on the world map!

Aage Myhre, Editor-in-Chief

TOPIC 1:

Lithuania’s peaceful fight for new freedom 1988 – 1991

The little stroke that fell the great bear and opened for the new era of a united Europe

|

|

|

|

Funeral of the victims of the 13 January 1991 Soviet attacks on Lithuania.

|

Professor Vytautas Landsbergis, January 1991. |

"Lithuanians, do not resist, your government has deceived you. Go home to your families and children."

This was the repeated announcement from the Soviet military ‘sound trucks’ rolling through the streets of Vilnius in January 1991. But luckily for Lithuania and for the new united Europe we today take more or less for granted, there was a music professor and a complete little nation that wanted it all differently. Hadn‘t it been for this peaceful fight for regained freedom against an occupation and a ruling the people of the Baltic States never wanted or agreed to, the map of Europe would most likely have looked very different today...

If there were those in the West who hadn’t heard about Lithuania before, they almost certainly had by the end of the day, 13 January 1991. That was the day Soviet troops cracked down in Vilnius and the resulting bloodshed made headlines around the world. The action was apparently a bid to stop Lithuania’s independence drive in its tracks. By the time the firing stopped and the smoke cleared, more than a dozen people lay dead, and hundreds more were injured. The crackdown, and particularly the killings at the TV tower, not only brought fame and sympathy to Lithuania from around the world, it was also a defining moment for Lithuanians themselves.

The bloodshed meant they had crossed a point of no return. If there was ever any notion of reconciling with Moscow, it was now unthinkable. For those watching from abroad, Vytautas Landsbergis was the central player in the drama unfolding in Vilnius. The colourful, quick-tempered music professor became Lithuania’s president (or chairman of the Lithuanian Supreme Council) in 1990 and, from that time on, his name became almost synonymous with the Lithuanian independence movement. His blunt talk about breaking free of the Soviet Union and about Lithuania’s moral right to be able to do so startled observers in the West almost as much as it infuriated the Kremlin.

See also: https://vilnews.com/?p=3642

TOPIC 2:

South Africa, home to 70.000 Lithuanian Jews

|

|

|

|

“This postcard was the last sign of life my father had from his father. It was sent from my grandfather’s home here in Kupiskes (North Lithuania) in March 1941 to my father’s new home in Pretoria (South Africa), but my grandfather was most probably already dead when the postcard reached Pretoria late summer 1941. He was killed by the Nazis”.

Attorney Ivor Feinberg, Lithuania’s consul in Pretoria, is obviously very touched when he visits his grandfather’s house in Kupiskes, telling us about the last memory of his grandfather – a memory not unlike many other stories related to the about 70.000 Jews of Lithuanian descent living in South Africa.

|

|

Lithuanians dominate the Jewish community in South Africa to an extent seen in no other country, even their former home. "We have around 80.000 to 90.000 Jews in South Africa, and about 80 percent of them are of Baltic descent, most of them from Lithuania," saYS David Saks, an historian and researcher at the Jewish Board of Deputies in Johannesburg. "We probably have the most 'Lithuanian' Jewish community in the world," said Saks, whose own grandparents came from Lithuania.

This ratio even exceeds that of Lithuania itself as most of the Baltic State's small Jewish community, now numbering a mere 5.000, is comprised mostly of immigrants who arrived from different parts of the Soviet Union after World War Two.The war devastated Lithuanian Jewry, once a leading centre of Jewish thought and culture. Historians estimate that 94 percent of the country's pre-war Jewish population of 220.000 perished in the Holocaust. The capital Vilnius, once known as the Jerusalem of the North, was home to a thriving community of 60.000 Jews, with more than 90 synagogues and the biggest Yiddish library in the world. Aside from one functioning synagogue, few traces of its rich Jewish past remain.

"South Africa is more Litvak than Lithuania itself...we see our culture and society have been preserved there," says playwright and novelist Mark Zingeris, one of the few Litvaks remaining in Lithuania.

See also: https://vilnews.com/?p=1703

TOPIC 3:

Italy’s extraordinary, little known role in Lithuania

|

|

|

|

|

Sigismund the Old |

Bona Sforza

|

The Royal Palace – once again being rebuilt |

When Lithuania’s Grand Duke Sigismund the Old in 1518 married the Italian Princess Bona Sforza, this became another outstanding manifestation of the already strong relationship between Italy and Lithuania.

The royal couple created together an Italian community within the court and Italian culture became the preoccupation of the Vilnius city elite. Macheroni, skryliai, and even the confection marcipanus became staples among the cogniscenti and life at court became a series of cultural events, with rich noblemen competing for extravagance. During the rule of Sigismund the Old the palace was greatly expanded, to meet the new needs of the Grand Duke and Duchess. Another wing was added, as well as a third floor and the gardens were also extended. The palace reconstruction plan was probably prepared by Italian architect Bartolomeo Berrecci da Pontassieve.

The Royal Palace – that now again is being rebuilt – was remodelled by Bona Sforza and Sigismund the Old in Renaissance style. The plans were prepared by Italian architects, including Giovanni Cini da Siena, Bernardino de Gianotis Zanobi, and others. Among the many visitors to the Palace was Ippolito Aldobrandini, who later became Pope Clement VIII, also this emphasizing the extraordinary connections between Italy and Lithuania that lasted for hundreds of years – also giving background for the saying that ‘Vilnius is the world’s most Italian city outside Italy’.

Throughout the Renaissance, when Italy was the leading trading centre and a melting pot for the world’s greatest civilizations, also Vilnius also became a leading Renaissance centre of world class, competing only with Florence and Milan.

See also: https://vilnews.com/?p=2927 and https://vilnews.com/?p=1652

TOPIC 4:

The Lithuanian-Americans, a nation outside the nation

|

|

|

|

Ex-President Valdas Adamkus is today’s most famous US-Lithuanian

|

Distribution of Lithuanian-Americans according to the 2000 census |

Many Lithuanians immigrated to the New World before the American Revolution. The first may have been a Lithuanian physician, Dr. Aleksandras Kursius, who is believed to have lived in New York as early as 1660. Most of the other Lithuanians who ventured to the Americas during this period were members of the noble class or practitioners of particular trades. But the first really significant wave of Lithuanian immigration to the United States began in the late 1860s, after the American Civil War. During the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, an estimated 300,000 Lithuanians journeyed to America. A flow that was later halted by the combined effects of World War I, the restriction of immigration into the United States and the achievement in 1918 of Lithuanian independence.

The second wave of immigration had a greater impact on U.S. census figures. Following World War II, a flood of displaced refugees fled west to escape the Russian reoccupation of Lithuania. Eventually 30,000 Dipukai (war refugees or displaced persons) settled in the United States, primarily in cities in the East and the Midwest. These immigrants included many trained and educated leaders and professionals who hoped to return someday to Lithuania. The heightening of tensions between the United States and the Soviet Union—known as the Cold War—dampened these expectations, and many Lithuanians sought to create a semi permanent life in the United States. By 1990 the U.S. Bureau of the Census listed 811,865 Americans claiming "Lithuanian" as a first or second ancestry.

The main areas of Lithuanian settlement in the United States included industrial towns of the Northeast, the larger cities of the Northeast and the Midwest, and the coal fields of Pennsylvania and southern Illinois. According to the 1930 census report, only about 13 percent of Lithuanians lived in rural areas, and even fewer—about two percent—were involved in agriculture. Nearly 20 percent of all Lithuanian immigrants settled in Chicago alone. Throughout the twentieth century, Lithuanian Americans began to climb up the economic ladder and gain an important place in their local communities. This mobility allowed them to enter the American mainstream.

Two important developments in Lithuania led to the growth of a strong Lithuanian American ethnic identity: the late nineteenth-century rise of Lithuanian national consciousness and the achievement of Lithuanian independence in 1918. Lithuanian Americans were staunch supporters of their newly independent homeland during the 1920s and 1930s, and some even returned to assist in the restructuring of the country's economy and government.

The post World War II wave of Lithuanian immigrants—the Dipukai—also experienced a surge of Lithuanian consciousness. These later immigrants saw themselves as an exiled community and clung to their memory of two decades of freedom in Lithuania. They developed an extensive network of schools, churches, and cultural institutions for the maintenance of Lithuanian identity in the United States.

|

FAMOUS AMERICAN-LITHUANIANS (there are many more) |

||||||

|

The very first FBI Director, 1912-1919 |

Al Jolson (1886-1950) Singer and Entertainer |

(1921 – 2003) Movie Star |

Marija Gimbutiene (1921-1994) Archeologist

|

Birute Galdikus (1946 - ) Anthropologist, world leading authority on orangutans |

Dr. Juozas P. Kazickas (1918 - ) Business entrepreneur |

|

See also:

TOPIC 5:

Lithuania and India - same language root and more…

|

|

|

Pictures: Aage Myhre

Pictures: Aage Myhre

It’s early morning in Delhi, India. I have been invited to the small, dark office of Professor Lokesh Chandra, one of India’s leading experts on Sanskrit and Buddhism. “The same year I was born, 1927, my father went to London to get a degree in Lithuanian language. He spoke the language fluently, but he never visited Lithuania”, tells the elderly professor, still with his Kashmir coat and cap on, despite the outside temperature of close to 300 Celsius. And I soon learn that the professor’s knowledge about the connections between Old Sanskrit and the Lithuanian language and ancient cultural ties between India and Lithuania is nothing but amazing…

It is a common belief that there is a close similarity between the Lithuanian and Sanskrit languages; Lithuanian being the European language grammatically closest to Sanskrit. It is not difficult to imagine the surprise of the scholarly world when they learned that even in their time somewhere on the Nemunas River lived a people who spoke a language as archaic in many of its forms as Sanskrit itself. Although it was not exactly true that a professor of Sanskrit could talk to Lithuanian farmers in their language, coincidences between these two languages were truly amazing, for example:

Sanskrit sunus - Lithuanian sunus; son Sanskrit viras - Lithuanian vyras; man

Sanskrit viras - Lithuanian vyras; man

Sanskrit avis - Lithuanian avis; sheep Sanskrit dhumas - Lithuanian dumas; smoke

Sanskrit dhumas - Lithuanian dumas; smoke

Sanskrit padas - Lithuanian padas; sole

We can assert that these Lihuanian words have not changed their forms for the last five thousand years!

Read also: https://vilnews.com/?p=4425 and https://vilnews.com/?p=4434

TOPIC 6:

Lithuania turned 1000 years in 2009!

"In 1009 St Bruno, who is called Boniface (Bonifatius), Archbishop and monk, in the second year of his conversion, on the border between Russia and Lithuania (Lituae), having been hit on the head by the pagans, and his 18 men went to heaven on the 23rd of February. "There are several sources that mention the event - the killing of the missionary but they refer to Prussia rather than Lithuania, which proves that both Germans and Poles did not know about the existence of Lithuanians then. They thought that Prussians were the only Balts (or the majority of Balts). Quedlinburg Annals mentioned Lithuania because they were keen on precision and the information was received from St Bruno's entourage. The story about St Bruno describes the political organisation of Lithuanians, which was peculiar and not characteristic of other Baltic tribes before the 13th century.

TOPIC 7:

Modern Lithuania in a new Europe

|

|

Lithuania has shown an impressive performance since its liberation from the USSR. The world recession was, however, hitting very hard, and there is now acutely necessary to search for new growth resources. A new growth cycle of the economy should focus on incentives and promotion of higher-quality high-tech industries, through R&D support, high-tech industry incubators, and appropriate educational focus.

The general strengths of Lithuanian national innovation system lies in the well developed and continuing its academic tradition higher education sector with strong science and technology research tradition and engineering orientation.

This results in a relatively high share of the population with tertiary education, high numbers of S&T graduates among them, and cultural orientation of the younger generation towards higher education. However, restricted resources for R&D and the higher education sector combined with the growing numbers of students at all higher education levels doubts the quality of education, especially in areas where technological based education is significantly important. Also low or non existing investments of businesses in vocational training lead to obsolete qualifications not suitable for high tech high skill work. The weak links between business and higher education and R&D communities result not only in obsolescing qualifications of the highly educated labour force, but also in low value added innovations, developed without input from the R&D sector.

TOPIC 8:

Karaims and Tatars - Turkish nationalities in Lithuania

|

|

|

|

Typical Karaim house in Trakai, 30 km from Vilnius city. |

A senior Tatar Muslim cleric (akhund) |

Since the 14th Century two Turkish nationalities – Tatars and Karaims – have been living in Lithuania. From linguistic and ethno genetic points of view they belong to the oldest Turkish tribes - Kipchaks. This ethnonym (Kipchak) for the first time was mentioned in historical chronicles of Central Asia in the 1st millennium BC. Anthropologically ancient Kipchaks were very close to Siberia inhabitants Dinlins, who lived on both sides of the Sajan Mountains in Tuva and the northern part of Gob. In the 5th century BC Kipchaks lived in the West of Mongolia, in the 3rd century BC they were conquered by Huns. Since the 6 - 8 centuries, when the first nomadic Turkish empires were founded, the Kipchak’s fate is closely connected with the history and migration of the Middle Asia tribes. In Turkish literature they are known as Kipchaks.

The history of Karaims is connected with Lithuania since 1397-1398. According to the tradition, The Great Duke of Lithuania, Vytautas, after one of the marches to the Golden Horde steppes, had to bring from the Crimea several hundred Karaims and settle them in the Great Duchy of Lithuania. Transference of several hundred Karaim families and several thousand Tatars was not done once. It was in connection with the state policy of The Great Duchy to inhabit the empty areas, build towns and castles and to develop trade and economic life.

Initially, Karaims were settled in Trakai between the two castles of The Great Duke, present Karaim Street. Later they were found living in Biržai, Naujamiestis, Pasvalys and Panevėžys. However, Trakai has always been the community's administrative and spiritual centre for Karaims in Lithuania, nowadays more and more also for Karaims throughout the world.

See also: https://vilnews.com/?p=2942

TOPIC 9:

Lithuania 500 years ago was Europe’s largest country

|

|

|

|

Vytautas the Great (1350-1430). |

The Grand Duchy of Lithuania, 13-16 centuries. |

|

|

|

“Lithuania was a superpower much longer than USA has been“. This is how I often tease my American friends arriving in Vilnius. But the teasing is in fact not so far away from reality, as the Grand Duchy of Lithuania (GDL) for 300 years was one of the leading and largest nations of the World – the largest in Europe – stretching from the Baltic Sea to the Black Sea.

It all started with King Mindaugas (1203-1263), Lithuania‘s first and only king, who in 1236 defeated the Livonian Brothers of the Sword and united the different Lithuanian tribes under his reign. But the real expansion began when Grand Duke Gediminas (1275 – 1341) came to power in 1316, and started a new dynasty of leaders.

Gediminas employed several forms of statesmanship to expand and strengthen the GDL. He invited members of religious orders to come to the Grand Duchy, announced his loyalty to the Pope and to his neighbouring Catholic countries and made political allies with dukes in Russia as well as with the Poles through marriage to women in his family.

Gediminas’ political skills are revealed in a series of letters written to Rome and nearby cities. He makes mention of the Franciscan and Dominican monks who had come to the GDL by invitation and were given the rights to preach, baptise and perform other religious services. He also included an open invitation to artisans and farmers to come and live in the GDL, promising support and reduced taxes to those who would come.

Grand Duke Gediminas is my personal favourite among all the Lithuanian nobles, and in my opinion, he was one of the greatest rulers of medieval Europe. He was a man of extraordinary knowledge and wisdom, understanding the importance and advantage of having a multicultural society as the foundation for his new city, more cleverly than most world rulers during the centuries after him. In October 1323, for example, representatives of the archbishop of Riga, the bishop of Dorpat, the king of Denmark, the Dominican and Franciscan orders, and the Grand Master of the Teutonic Order assembled in Vilnius when Gediminas confirmed his promises and undertook to be baptized as soon as the papal legates arrived. A compact was then signed in Vilnius, in the name of the whole Christian World, between Gediminas and the delegates, confirming the promised privileges. Fifteen months later, on the 25th of January 1325, Gediminas issued circular letters to the principal Hansa towns in Europe offering a free access into his domains to men of every order and profession from nobles and knights to tillers of the soil. The immigrants were to choose their own settlements and be governed by their own laws. After Gediminas, Vilnius emerged over hundreds of years, expanding, changing, and embodying the creative imagination and experience of many generations of architects and builders from Lithuania and abroad. Under the care of generous and perceptive benefactors, it became a city rich in architectural treasures and urban harmony.

Under Vytautas the Great (1350-1430), Lithuania‘s military and economy grew even stronger, and he was the one expanding the Grand Duchy‘s frontiers south to the Black Sea. The Grand Duchy was at its largest by the middle of the 15th Century. It existed in the very centre of Europe and comprised the entire territories of contemporary Lithuania, Belarus, Ukraine, a part of Poland and stretched from the Baltic Sea to the Black Sea. Both Belarus and Ukraine point back to the days when they were part of the thriving GDL as proof of their cultural and political distinction from Russia.

Successfully ruled by a dynastic line of dukes, the Grand Duchy of Lithuania (GDL) developed a highly advanced system of state administration and stove off invading Crusaders longer than any other Central European power. Its statesmen conducted effective foreign policy and military campaigns and created a multi-ethnic state. Though officially ended in 1795, the history of the GDL continues to influence modern-day nationalist thinking in the region. Not only Lithuania but also Belarus and Ukraine remember the days when they were part of the thriving GDL as proof of their cultural and political strength clearly distinguishing them from Russia.

See also: https://vilnews.com/?p=326

TOPIC 10:

Lithuania’s new international role:

A bridge at the crossroads of east-west-south-north

|

|

|

Today Lithuania is in a unique position to continue and expand its role as a significant transportation hub and meeting point for many neighbouring regions. Lithuania serves as a natural bridge for East - West (Europe-Asia) traffic with transport connections to the Trans-Siberian rail route and direct links with Russia and other countries of the former Soviet Union, as well as rapidly growing Baltic countries and even East Asia, including China. Nearly half or 45% of Russia’s total foreign trade passes through the Baltic Sea ports. A major advantage of Lithuania lies in its strategic location at the crossroads between Eastern and Western Europe as well as the Baltic Sea region. Lithuania has for centuries been on an important trade route, linking the Baltic Sea Region to the Black Sea. Klaipeda, the country’s sea coast city, has moved from having been an important port city in the Hanseatic League of trading cities around the Baltic and North Sea since the 13th century, to becoming a modern logistic hub for trade and transport between Western and Eastern Europe. Its unfrozen port is the best transportation centre between the east and west. Vilnius, the capital of Lithuania, is together with the country‘s second largest city, Kaunas, developing into a huge metropolis, showing all the potential of becoming a significant commercial, financial and transportation centre for the Baltic Sea region and Northern Europe. Traditions and experience gained during many centuries and historically strong presence of people from many nations and backgrounds are important for conducting economic relations nowadays. In addition, Lithuania is located in one of the most dynamic and competitive areas of the world representing 10 metropolitan areas with over 90 million inhabitants and being the home to well-established companies and product brands and the leading IT and telecom producing area of Europe with the highest cellular telephone penetration in the world.

TOPIC 11:

For hundreds of years Lithuania was home to amazingly thriving Jewish communities

|

|

|

|

|

LEFT: The Great Gaon of Vilnius - Elijahu ben Solomon Zalman (1720-1797) was the greatest luminary not only among the many Talmudical scholars of the 17th and 18th centuries, but also for many later generations.

RIGHT: A typical ‘Jewish’ Vilnius street, early 20th century.

|

||

Napoleon Bonaparte was the one who started calling Vilnius ‘Jerusalem of the North’, when he arrived here in June 1812. It was the first and only "Jewish city" Napoleon would ever see. It is said that he became very surprised on what met him in Vilnius, a city so far away from mainstream Europe and still with a lively Mediterranean mood and life.