THE VOICE OF INTERNATIONAL LITHUANIA

|

VilNews has its own Google archive! Type a word in the above search box to find any article.

You can also follow us on Facebook. We have two different pages. Click to open and join.

|

Featured

- Posted by - (7) Comment

Two new

VilNews editors!

Today, we are pleased to announce that VilNews has got two new skilled Associate Editors, Dalia Cidzikaite and Daiva Repečkaitė. We can say with certainty that they are going to mean a lot for our worldwide, online e-publication and the accompanying wonderful network of global readers with Lithuania in their hearts. Please welcome them! See also our Section 2 and Section 3.

Associate Editor

DALIA CIDZIKAITE

Dalia is the former editor in chief of the Chicago-based Lithuanian newspaper Draugas. She holds a PhD from the University of Illinois at Chicago. She is the board member of the journal Lituanus, Santara-Šviesa Federation, also the member of the Lithuanian American Community, Inc. Archives Committee and Association for the Advancement of Baltic Studies. Dalia is the author of a book The Other in Lithuanian Prose (Vilnius: Lietuvių literatūros ir tautosakos institutas, 2007). She was born

Dalia is the former editor in chief of the Chicago-based Lithuanian newspaper Draugas. She holds a PhD from the University of Illinois at Chicago. She is the board member of the journal Lituanus, Santara-Šviesa Federation, also the member of the Lithuanian American Community, Inc. Archives Committee and Association for the Advancement of Baltic Studies. Dalia is the author of a book The Other in Lithuanian Prose (Vilnius: Lietuvių literatūros ir tautosakos institutas, 2007). She was born

and grew up in Vilnius.

dalia.cidzikaite@VilNews.com

Associate Editor

DAIVA REPEČKAITĖ

Daiva is a former journalist of Atgimimas weekly, the Baltic correspondent of the Equal Times, and a freelance reporter. She has published articles in IQ magazine, news sites Delfi, lrytas.lt and Bernardinai.lt, as well as Cafe Babel, Göteborgske Spionen and Grads.co.uk. In 2008 she won the European Young Journalist Award "Enlarge your vision" in the Lithuanian language category and later was awarded a Japan Foundation grant for young researchers and journalists. In addition to Lithuanian and English, she speaks German, Russian and Hebrew, as well as some Swedish, French and Japanese.

Daiva is a former journalist of Atgimimas weekly, the Baltic correspondent of the Equal Times, and a freelance reporter. She has published articles in IQ magazine, news sites Delfi, lrytas.lt and Bernardinai.lt, as well as Cafe Babel, Göteborgske Spionen and Grads.co.uk. In 2008 she won the European Young Journalist Award "Enlarge your vision" in the Lithuanian language category and later was awarded a Japan Foundation grant for young researchers and journalists. In addition to Lithuanian and English, she speaks German, Russian and Hebrew, as well as some Swedish, French and Japanese.

daiva.repeckaite@VilNews.com

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - (0) Comment

LITHUANIA’S BEST RESTAURANTS

TripAdvisor chooses Druskos Namai

TripAdvisor.com has selected Lithuania’s best restaurants.

Druskos Namai in Užupis, Vilnius, tops the list!

TripAdvisor is a travel website that assists customers in gathering travel information, posting reviews and opinions of travel related content and engaging in interactive travel forums. TripAdvisor was an early adopter of user-generated content. The website services are free to users, who provide most of the content, and the website is supported by an advertising business model.

THE DRUSKOS NAMAI PHILOSOPHY

We prepare our food in accordance with the principles of modern European cuisine using the best quality Lithuanian products.Preference is given to products supplied by farms located close to Vilnius. Menu changes often - dishes of depends on what kind of fresh produce on a daily basis we receive from manufacturers and what's available at the time of the year.

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - (0) Comment

Searching for the Holy Grail?

Come to Vilnius!

Forget Rosslyn Chapel in Scotland. Forget the Louvre Museum in Paris. If you're among the millions who have read Dan Brown's book 'The Da Vinci Code', you have probably also made some reflections on how the Holy Grail disappeared, virtually without a trace, after Leonardo da Vinci died in 1519. In that case I will now give you some hints and clues that you can begin to investigate.

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - (0) Comment

NEW!!

VilNews section 7:

VILNEWS E-SHOP FOR

LITHUANIAN PRODUCTS

We in VilNews want you who read us to feel connected to Lithuania, wherever in the world you live. We have now decided to expand our offerings to include various Lithuanian products that we think many can enjoy and benefit from.Lithuanian music, literature, art, linen, food-related products and more are now for sale via our VilNews E-Shop. Welcome to what we hope will bring you even closer to Lithuanian traditions and specialties!

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - (0) Comment

While we shelled

beans with him

an interview of Myra Sklarew

By Ellen Cassedy

ellen@ellencassedy.com

Myra Sklarew is the author of numerous books of poetry, including The Witness Trees, a powerful account of how she forged – and is still forging – a connection to her Jewish heritage in Lithuania. VilNews correspondent Ellen Cassedy spoke with Sklarew in Washington, D.C.

Myra, you have visited Lithuania twelve times in 18 years. What first drew you to the land of your ancestors?

In 1993, it occurred to me that with the end of the Soviet occupation, I could walk freely. I went with no knowledge. I didn’t know a soul and didn’t know the language. I just started walking.

Let’s listen to how you put it in The Witness Trees, your book-length poem with a Yiddish translation by the noted late Yiddish poet David Wolpe (a member of your Lithuanian Jewish family who immigrated to South Africa):

I wanted to go there

by feel, to see if Lithuania would tell me

its secrets, to see if I would

recognize myself in Lithuania, to marry the myth

of who I am with the myth of place. To find more

than the signs of the dead. To find evidence

of the lives of those I have come from.

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - (1) Comment

While we shelled beans with him

an interview of Myra Sklarew

by Ellen Cassedy

Myra Sklarew is the author of numerous books of poetry, including The Witness Trees, a powerful account of how she forged – and is still forging – a connection to her Jewish heritage in Lithuania. VilNews correspondent Ellen Cassedy spoke with Sklarew in Washington, D.C.

Myra, you have visited Lithuania twelve times in 18 years. What first drew you to the land of your ancestors?

In 1993, it occurred to me that with the end of the Soviet occupation, I could walk freely. I went with no knowledge. I didn’t know a soul and didn’t know the language. I just started walking.

Let’s listen to how you put it in The Witness Trees, your book-length poem with a Yiddish translation by the noted late Yiddish poet David Wolpe (a member of your Lithuanian Jewish family who immigrated to South Africa):

I wanted to go there

by feel, to see if Lithuania would tell me

its secrets, to see if I would

recognize myself in Lithuania, to marry the myth

of who I am with the myth of place. To find more

than the signs of the dead. To find evidence

of the lives of those I have come from.

Your family lived in the Kedainiai region?

Yes – in the town of Kedainiai itself, and also in 15 different villages, including tiny hamlets that are not even on the map. I was most curious about these little villages.

In Datnuva, where my family was once more than half the town, an elderly woman called out to me – she cried out – as we drove in. She looked very intently at my face and told me I looked exactly like someone she once knew. It turned out she’d known my whole family. I visited with her every year and took my granddaughter to meet her and her family.

Do you have advice for others who are considering a visit?

The most important things happen by happenstance, by walking. Save time to walk in the villages your family came from. Take chances, take risks. Don’t be afraid to talk to elderly people on the street. Remarkable guides and friends have made this possible for me.

Once on a very cold day in October, my guide and I came upon an elderly man shelling dried beans to store for winter. We sat down beside him, and while we shelled beans with him we asked – “How do you feel about Jewish people? What happened when the Jews were taken away? What did your children make of it?”

September 25, you plan to go to Kedainiai to attend a commemorative event at the site where more than two thousand Jews were shot in the summer of 1941 – including dozens of your own family members. New plaques will be unveiled, listing names of the victims. Why do you want to be there?

If you want to love where you come from, you can’t omit the sorrow. I never cease to discover things in Lithuania. There are lessons I am still learning about the cruelty we’re all capable of, and lessons about other ways of behaving. I always try to visit people who rescued Jews during the Holocaust, to figure out how they had the courage.

I’m particularly touched that not only Jewish descendants but the people of Kedainiai today, especially the Kedainiai Regional Museum, will bring this new memorial into being.

These lines from The Witness Trees (Dora Teitelboim Center for Yiddish Culture/Cornwall Books: 2000) speak eloquently about what you’ve found in Lithuania – and why you will continue to go back. Thank you for sharing your story with us.

Here in America, if you rise early enough, in the dark,

if you go out of doors, you can smell autumn

though it is still August. Here and there, leaves are beginning

to fall, a few under the dogwood tree, oak leaves, poplar. And just

after dusk, when the earth passes through the dust stream of old

comets, if you look up you will see

meteor showers, the Perseids. Are these burning songs

striking at our atmosphere, like the hearts

of those who met their deaths untimely in Lithuania?

I tell you, once we have found our dead, though we cannot hear their

answering voices among the sounds of this world, we will tear

open the skin of the earth

to admit them. We will not lose them again.

Ellen Cassedy traces her Jewish family roots to Rokiskis and Siauliai. Her book, We Are Here: Memories of the Lithuanian Holocaust, will be published in March of 2012. She lives in Washington, D.C. Visit her website at www.ellencassedy.com.

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

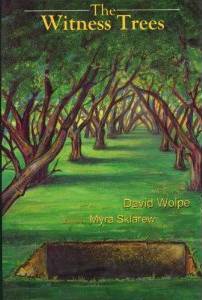

Back cover of Laima Vince’s book

“Forest Brothers: The Account Of An Anti-Soviet Freedom Fighter - Juozas Lukša.”

I have travelled in several former Warsaw Pact countries. In Hungary I met a person who participated in their 1956 uproar. In Slovakia and the Czech Republic I talked to people about their ‘Prague Spring’ of 1968. The people I talked to were rightfully proud of the uproars their countries performed against the mighty USSR, but when I asked them about the revolts that took place here in Lithuania and the other two Baltic states during the period of 1944-53, they all lacked concrete answers and knowledge. “We simply didn’t know,” they told me...

And they are not alone. I believe very few in the entire world have ever heard about the guerrilla war that took place here in the very centre of Europe after World War II, even if the number of victims in fact can be compared to the Vietnam War (1960-75).

It has been estimated that the losses of the Lithuanian partisan war’ amounted to 70,000 Soviet soldiers and 22,000 Lithuanian ‘Forest Brothers’, making this war one of the longest and bloodiest guerrilla wars in the history of the world.

For comparison, the United States lost 58,000 soldiers in Vietnam.

The outcome of this uneven war became an extremely sad and gruesome chapter in Lithuania’s history. Some 132,000 individuals were captured and deported to the Arctic areas of Siberia, 70% of them children and women, and more than 50,000 of these fine people died under the extremely harsh conditions up north, never able to return to their homeland alive.

During the same period, another 200,000 people were thrown into prisons. Over 150,000 of them were sent to the Gulags, the USSR’s concentration camps. These mass deportations continued until the death of Josef Stalin in 1953, but many prisoners remained in the camps also during the time of Nikita Khrushchev.

In a book by Anatol Marchenko published in Germany in 1973, he tells about his experiences from Soviet prisons and concentration camps in the early 1960s. One of his stories is about three Lithuanian prisoners who tried to escape from the convoy in a forest. Two of them were quickly caught, then shot many times in the legs, then ordered to get up which they could not do, then kicked and trampled by guards, then bitten and torn up by police dogs and only then stabbed to death with bayonets. All this with witty remarks by the officer, of the kind; "Now, free Lithuania, crawl, you'll get your independence straight off!"

This is one of thousand stories you can read in many now available books about the Soviet horrors. From 1917 to 1991, politics in the USSR started and finished with the Communist Party; it was the only game in town.

What passed for elections were a contest between members of the same political party - no candidates other than communists were allowed to run. The people who ruled the country were dictators; some more brutal than others. The Communist Party owned everything - land, factories, housing, and farms. The masses went about their daily lives under the direction of the Party. They were told where to live, where to work, and where to travel. There was very little freedom of choice in anything. The ideal behind this system was that everyone lived and worked for the good of the community.

But, the power of the Soviet Union, under the domination of Russia, was built on sand not rock. Under communism, individuals learned to lie back and do nothing and the idea of everything being owned by the community instead of individuals meant that nobody felt responsible for upkeep and maintenance; or as it is expressed in a Spanish proverb: "The cow of many is well milked and badly fed."

But even if there existed both humor and good days for people during those years, the extreme sufferings the USSR meant for this part of Europe should never be forgotten, and the Lithuanian partisan war is certainly one of the most important stories to tell our posterities along with the stories about Czechoslovakia in 1968 and Hungary in 1956.

I suggest you to read the books of Laima Vince (Forest Brothers: The Account Of An Anti-Soviet Freedom Fighter -Juozas Lukša), Ruta Sepetys (Between shades of gray) and Antanas Sileika (Underground).

Have a look at their web pages:

LAIMA VINCE – http://www.laimavince.com/forestbrothers.html

RUTA SEPETYS – http://www.betweenshadesofgray.com/

ANTANAS SILEIKA – http://antanassileika.ca/

Aage Myhre,

Editor-in-Chief

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - (1) Comment

Antanas Sileika

Stories from behind

the iron curtain

I sit outside and drink coffee with Antanas Sileika this beautiful summer

morning in Vilnius, as he tells me about his latest novel, Underground.

By Aage Myhre

aage.myhre@VilNews.com

I sit outside and drink coffee with Antanas Sileika this beautiful summer morning in Vilnius. The award-winning Canadian-Lithuanian writer is visiting the country his parents fled during the Second World War. He is here to promote his latest book, Underground, which probably also comes in Lithuanian edition this autumn. The novel, which can be bought through Amazon Canada, tells the problematic love story of Luke and Elena, two members of the Lithuanian partisan revolt against the Soviet Union in the middle of the 1940s.

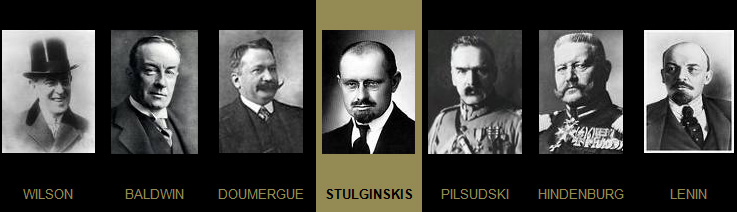

His visit to the fatherland has also another purpose, namely to gather information for his next book, and he tells me that the new novel will have the early 1920's as backdrop, the years when Lithuania just had begun to re-develop the country after more than 100 years of occupation by Tsar Russia.

But this summer morning, we focus on the period after World War II. The below 5-chapter essay speaks for itself…

|

Below an essay Antanas Sileika has written about himself, his novel, |

1) Love and Loss Among the Ruins

In 1946, Winston Churchill’s created a powerful metaphor when he said that an “Iron Curtain” had descended over Eastern Europe, and that political metaphor seemed to hold longer than most, until 1991, when the Soviet Union collapsed and the captive republics flew away like birds escaping from an unlatched cage.

So much for the curtain. Or so it seemed.

The metaphor of the iron curtain actually remained as strong as ever for almost twenty years longer because we in the West remained ignorant of the stories that had unfolded behind it, what it meant to live there. It was only after 1991 that memoirists began to write and historians began to work in the newly opened archives both in Russia and among the various former Soviet republics.

It’s only now that their stories are coming out.

In Western Europe and North America, we laid down our arms after WW2 and set about making a baby boom, and then building the suburban houses to put the children in. Later, we filled those houses with televisions and refrigerators with the help of Mad Men who told us what brands to purchase. We built garages for our cars and paved roads for them to drive upon.

But in Eastern Europe, particularly in the Baltics and Ukraine and to a certain extent in Poland, terror set in. Farmers were dispossessed of their land, businesses were taken away, and teachers, policemen, journalists and former government bureaucrats were shipped out to the gulag where many of them died of hunger or exposure.

An underground resistance sprang up by 1944 and it fought the Soviets for another nine years. At first, pitched battles took place in forests and swamps. Whole towns were seized by the partisans. The fight eventually settled down into a guerilla war during which the partisans owned the countryside by night.

And they fought while waiting for the West, believing that if the war was started because of Poland, surely the West would not forget that country or the others nearby.

For those interested in the history of the period, the last decade and a half have been illuminating, beginning with the appearance of Norman Davies’s Europe, followed by the late Tony Judt’s Postwar, and culminating in the recent Bloodlands, by Timothy Snyder. And there are many more histories now on the subject of Eastern Europe, so many that there is a danger of narratives in collision, particularly for the way the Holocaust fits in among the other crimes of that time.

But I’m not interested in the facts themselves. I’m interested in what they mean, and I am interested in the lives of people under great stress during those times.

In 1942, in the film Casablanca, Humphrey Bogart said to Ingrid Bergman as he sacrificed himself by giving up his flight to safety to another, more worthy man, “I’m no good at being noble, but it doesn’t take much to see that the problems of three little people don’t amount to a hill of beans in this crazy world.”

That was what people believed then. We don’t believe that any more. In our time, we believe the personal is more important than the political.

I take this insight and then I wonder: what was it like to be in love under impossible political conditions behind the newly-created iron curtain in the forties and early fifties?

Although the revelations about Eastern Europe are new, I wanted to tell a very old story of a man who goes to war and after much killing, and nearly being killed himself, wants nothing but to return to the women he loves, the woman he made promises to.

It’s the story of a man who wants to go home, even if that place is no longer the home he left.

I’m interested in a story of love and the loss of it among the ruins.

* * * * * *

2) John Le Carre Territory

I did not set out in my writing life intending to write about the postwar period and I did particularly did not want to write about Lithuania. My parents came from that part of the world and they gave me the language, but English is still my strongest language and I have been an anglophile since my childhood, when I imagined myself Sherlock Holmes, or someone slightly more complex, like Lord Jim. I imagined myself a character out of Kipling, an inhabitant of the British Commonwealth whose pink-coloured countries dominated the maps of the world that were found in schoolrooms into the sixties.

On top of that, in the sixties and seventies, everyone was loose left and I was too, and I found the anti-Soviets of that time, including my parents, embarrassing for their squareness. In my callow youth, I imagined the people with right attitudes about the world did not wear bad suits, or have funny accents.

But against my intentions, I was eventually lured into fascination with the stories of Eastern Europe in general and Lithuania in particular. After all, if one can see the universe in a grain of sand, one can see the whole world through the events in a small country.

The language, one of the gifts of my deceased parents, gave me a window into the happenings on the other side of the iron curtain. At the same time, life in Canada gave me the distance to reflect on the happenings from afar. And the stories that came out of there were so dramatic, so compelling, that I would have been a fool to look somewhere else for my material.

Eastern Europe is John le Carre territory. The British masterminded spy missions into postwar Lithuania, running a former German torpedo boat off Sweden in order to dump spies on the Lithuanian beaches. As late as 1953, Estonians, Latvians, and Lithuanians took their small arms and their radios and their cyanide tablets from the British handlers at MI6 and went inland to decipher the enigma of Soviet intentions.

A good quarter of the men the British used were actually double agents, and they sold out the rest to the KGB. Kim Philby, the English turncoat who spied for the Soviets, might have been involved. These doomed operations are exquisitely described in Liutas Mockunas’s Pavarges Herojus (luckily, I can read Lithuanian and have access to this title).

And the true-life stories are more varied than the grey of Le Carre. They even have tragicomic moments. For example, the British/Lithuanian agent, Anicetas Dukevicius, was promised ten pounds a week in pay by MI6. He was captured and imprisoned by the KGB on a mission inside Lithuania in 1953, but he was not executed. After Lithuania’s independence in 1991, he apparently went to the British embassy to ask for back pay plus accumulated interest. I don’t know if he received it.

The Americans were slow to get started, but they played in this game as well. In 1951, they sent Juozas Luksa and his fellow partisans into Lithuania in a low-flying plane from which they parachuted. He, too, was betrayed a year later, and lured into a trap and shot.

He had left behind him a wife in Paris who did not receive certain news of his death for six years. Four decades later, she published “Laiskai Mylimosioms”, a collection of their love letters.

As if all these stories were not compelling enough to get my fingers tapping on the keyboard, there’s also a personal element to the stories above. Because Lithuania, with only three million inhabitants, is such a small country, there are fewer degrees of separation among people, more coincidences.

Adolfas Ramanauskas, the man who wrote the most dramatic stories of anti-Soviet resistance and then was captured in 1956, tortured for a year and executed, had worked in an office with my mother and probably sat in the lunchroom with her. A paternal uncle of mine was a farmer who supported the partisans, and he was exiled to the gulag and died there for his trouble.

These stories, and not just the personal ones, are irresistible for their drama and pathos. Why would I bother to look anywhere else?

* * * *

3) The Past is Slippery

I once asked an audience at a talk at the Goethe Institute in Toronto if Germans were opposed to historical novels in the same way that some Canadian critics are. They looked at me as if I were a fool. What German writer could leave history unexamined? For that matter, what European could live ignorant of the past?

I have often heard it said that Europeans remember everything and learn nothing, but if that is true, it is also true most Canadians remember nothing and learn nothing.

The past is complicated. The past is slippery. We think one thing of it now and another thing of it tomorrow. Is it because we have changed or the past has changed? In her recent history, The Ghosts of Europe, Anna Porter quotes Faulkner who said, “The Past is never dead. It’s not even past.”

Some people believe all history is polemic, but I am not of that school. I believe the truth is down there somewhere among the shards of the past, and some of us need to be patient archeologists, piecing the shards together until they form a recognizable whole. That is the job of both the archeologist and the historian.

The job of the historical novelist is somewhat different. We writers in the past have to decide not only what the object was, but also the importance of it, the meaning of it. The writer of historical fiction imagines into the past. What was it like to be there? What did it mean to love then, and did it mean something different from what it means now?

The British historian and art critic, Simon Schama, says that the greatcoat buttons of six generations of soldiers can be found in certain parts of Eastern Europe. In my last visit to Merkine, a small town in South-East Lithuania, I saw monuments to German soldiers who fell in WW1, to Red Army soldiers who fought the Germans in 1944, to Red partisans who were killed in the forest and to Lithuanian partisans who fought the Reds until they were annihilated in the fifties.

Each one of these monuments represents a narrative, a version of history. If I add to the monuments above those alarming highway signs found throughout Lithuania, like tourist indicators, that point the way to the many sites where the Jews were massacred in the Holocaust, then we have layer and layer of sediment in our archeology of the past.

The patient sifter of the past might find one narrative or another, or he might find that one narrative collides with another. The Soviets saved what remained of the Jews of Eastern Europe, but the Soviets were the enemies of non-Jewish farmers, business owners, teachers, and lawyers and bureaucrats of the old order. Therefore each group remembers them differently.

What is the correct interpretation? We still need to struggle with the past.

* * * * *

4) The Minefield in Historical Fiction

Mine is an old-fashioned view of literature. I believe it has to be about something important, something moving, something illuminating about the human condition. Otherwise, I’d rather watch movies or read the New Yorker, skipping the fiction.

Which is not to say that a good thriller, a family melodrama, or a comic confection does not have its place.

Historical writing is arguably harder to write than fiction about the present.

First, there’s the problem of language. I’m always wondering if certain words can be used in a historical setting. When did we adopt the words deck, porch, and verandah, and which is the appropriate word for the period I am writing in? How do I make my characters speak as if they were in the past when the actual way people spoke in the past is intrusive in contemporary writing? How do I do this without sounding stiff or corny? I read the word scoot in a piece of historical writing and it feels too modern. But I cringe if I read words such as these: don (a cloak), lo (and it came to pass), behold (thine enemies). Language is a minefield in historical writing (mine fields were in use in sixteenth century Europe, earlier in China - thank God for Wikipedia and damn the way it wastes my time).

Second, there’s the problem of the way people thought then. If characters in the past were racists or sexists, or homophobic or anti-Semitic, should I “correct” their attitudes by introducing a forward-thinking character who points out the error? That’s much, much too corny. On the other hand, to depict the sins of the past straight up feels wrong too.

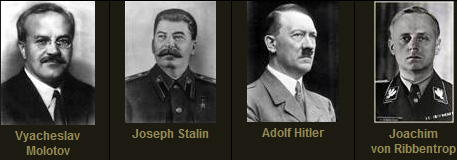

Third, there is the danger of using our superior knowledge to condescend to the past. Everyone in the past was somewhat less informed than any of us because we know how things turned out and characters in the past did not. We know that the Molotov - Ribbentrop pact split Eastern Europe between Germany and the Soviet Union, but at the time, the Baltics, Poles and Ukrainians did not. People in the past always seem slightly dumb (as we will appear to those who know how our current political turmoil in North Africa will play out in the long run.)

Fourth, fifth and sixth, there are the dangers of nostalgia, kitsch, and excessive enthusiasm for obsolete technologies (Who really needs to know how to use a scythe properly when harvesting wheat?).

As any historian knows, there are surprises in the past, and the same is true of writing historical fiction. I’m not religious, but it only occurred to me much later that “Underground”, the title of my novel, has meaning beyond the physical and the political. People kept burying their supposed dead in the novel, as well as their stories and feelings, but these kept returning, breaking back out of the clay in the novel, rising again and again. Sometimes, the obvious only becomes clear after the fact. I was writing about resurrection, it seems, but in a social sense, fired by memory and determination.

The dead soldiers, partisans, and victims were rising up from beneath their monuments.

* * * * *

5) Forever Stories

It’s not so much old stories that I look for in historical fiction as the forever stories.

A man flees a burning city and tries to find a new life. A woman chooses to kill to avenge her brother. Another woman, a long time ago, stands before her husband inside the breached walls of Troy and begs him not to go out to meet the Greeks who will surely kill him and make her a widow and a slave and her son an orphan. But her husband responds that no man escapes his fate; he must go out into battle, where he promises he will not give up his life so easily.

A few short years ago, as a parent, I stood before a young man and beseeched him not to go to war in Afghanistan, but nothing I said could stop him, and if his particular fate was luckier than that of many other soldiers, my anguish before the outcome was surely an echo of what Andromache said to her husband, Hector, in the Iliad.

This was a forever moment, one that was historical and forever present. The best of historical fiction gives us these kinds of moments:

Mark Helprin did it for adventure in A Soldier of the Great War; Annabel Lyon did it for Aristotle’s thought in The Golden Mean; Wayne Johnston did it for mixed motivations in Joey Smallwood in The Colony of Unrequited Dreams; Nino Ricci did it for a reconsideration of Jesus Christ in Testament.

Sometimes writers need to be explorers of the human heart, and sometimes explorers of geography; sometimes they need to be chroniclers of manners; they need to be the best craftsmen they can with the evasive and even fugitive meanings of language.

So why shouldn’t they be time travelers as well?

|

Antanas Sileika (Antanas Šileika) is a Canadian novelist and critic. He was born in Weston, Ontario - the son of Lithuanian-born parents. After completing an English degree at the University of Toronto, he moved to Paris for two years and there married his wife, Snaige Sileika (nee Valiunas), an art student at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts. While in Paris, he studied French, taught English in Versailles, and worked as part of the editorial collective of the expatriate literary journal, Paris Voices, run from the upstairs room of the bookstore, Shakespeare and Company. Upon his return to Canada in 1979, Antanas began teaching at Humber College and working as a co-editor of the Canadian literary journal, Descant, where he remained until 1988. After writing for newspapers and magazines, Antanas Sileika published his first novel, Dinner at the End of the World (1994): a speculative story set in the aftermath of global warming. His second book, a collection of linked short stories, Buying On Time (1997) was nominated for both the City of Toronto Book Award and the Stephen Leacock Award for Humour, and was serialized on CBC Radio's Between the Covers. The book traces the lives of a family of immigrants to a Canadian suburb between the fifties and seventies. Some of these stories were anthologized in Dreaming Home, Canadian Short Stories, and the Penguin Anthology of Canadian Humour. Antanas Sileika appears occasionally on Canadian television and radio as a free-lance broadcaster. His third book, Woman in Bronze (2004), compared the seasonal life of a young man in Czarist Lithuania with his subsequent attempts to succeed as a prominent sculptor in Paris in the twenties. His latest novel, Underground was released by Thomas Allen & Son in spring of 2011. The new novel is a love story set in the underground resistance to the Soviet Union in the late 1940s. He is the director for the Humber School for Writers in Toronto, Canada, and is a past winner of a National Magazine Award. |

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - (1) Comment

Underground:

A Novel by Antanas Sileika

Book review by DONNA BAILEY NURSE

in Canadian ‘The Globe & Mail’ http://www.theglobeandmail.com

“How are we going to survive unless we turn our hearts to stone?” a comrade warns the hero of Antanas Sileika’s

Underground. The question is an example of the elegant thinking that characterizes this rare and compelling chronicle of Lithuanian partisans and their violent struggle against Soviet occupation. Sileika’s third novel follows the military career of Lukas Petronis, whose bravery and commitment to the cause elevate him to legendary status within the resistance movement. Despite his heroism, Lukas keeps his heart from growing hard by falling in love with Elena, the sister of a partisan.

Underground, by Antanas Sileika, Thomas Allen, 305 pages, $24.95 Buy from: Amazon.ca Chapters Indigo

The story begins in 1944 with the Germans in retreat from Lithuania. With their departure, the dream of an education seems viable again, and Lukas and his younger brother, Vincentas, abandon the family farm on the edge of the Jewish Pine Forest for university in the city. Lukas studies literature while his brother enrolls at the nearby seminary. The buildings are dilapidated and the resources limited, but Lukas exhilarates in learning and the lively company of the students.

Unfortunately, the good times don’t last. The Russians have returned; and for the third time in a half-dozen years, Lithuania finds itself an occupied nation. Cattle cars rumble across the tracks – did they ever really stop? – packed with men, women and children exiled to Siberia. The secret police hound those citizens who remain; torture is commonplace, as is execution. Farmers must hand over to the government impossible portions of their modest crops.

Fed up with feeling powerless, Lukas and Vincentas head into the forest to join the freedom fighters. Whereas Vincentas’s spiritual, otherworldly nature could never adapt to harsh partisan life, Lukas takes to it easily. He turns out to be fearless, an excellent shot. In addition, his composition skills are put to good use. He is given the job of gathering international news and writing articles for the resistance papers.

From its opening lines, the novel strikes a haunting note. Some of this has to do with a ghostly presence: the hundreds of thousands dead, more than half of them Jews; a vast Jewish nation disappeared. The strange winter woodland setting also contributes to the tone. A formal military force, 30,000 strong, is scattered throughout the forests where the Russians fear to tread. Fighters reside in lean-tos or deep bunkers. Larger units emerge to engage the army in significant battles, while smaller groups ambush government officials and target organizations. It is in the woods that Lukas meets Elena, the sister of a comrade. The two eventually marry, but only after they massacre several Russian bureaucrats at their engagement party. They become folk heroes.

Sileika evokes the couple’s relationship with tender realism. His depiction of Elena, one of only a few female characters, also impresses. While she possesses curly brown hair and soulful eyes, it is her inner loveliness and determined nature that attract both Lukas and the reader.

We encounter Elena mostly through conversation, and through Lukas’s eyes. It would be nice to know her a little better, to get inside her head. Though dialogue in the novel is generally strong, spoken word never completely conveys a character’s thoughts and motivations.

Sileika’s portrayal of Vincentas suffers from a similar weakness: We see him mostly from Lukas’s perspective. That’s too bad, as Vincentas, who dreams of becoming a priest, represents a major theme in the novel: He embodies the deep-rooted presence of religion in the culture. Government disapproval means priests live in fear for their lives. Nevertheless, ordinary people cling to their prayer books, refer to their beliefs and continue to embrace the sacraments.

The debate surrounding partisan tactics derives from the Bible. “Harden not your hearts,” reads Hebrews 3:8. In one dark, ironic passage, Vincentas encourages a group of students to love one another: “How can you love the country if you don’t love the people in it?” He recoils from killing the enemy, preferring the path of passive resistance.

After a deadly grenade attack, a grief-stricken Lukas is sent away to the West to heal and to drum up support for the movement. The West is an important character in the story. The partisans expect anti-communist America to save them. In Stockholm, Lukas is infuriated by the unruffled neutrality of the Swedes. Blatant British self-interest equally aggrieves him. In Paris, his political sentiments seem out of fashion. Lukas cannot understand why Western governments worry about placating Stalin when Lithuanian people are being brutalized. Déjà vu all over again.

This story picks up speed as it goes along, hurtling into the future and an unanticipated conclusion. On occasion the prose is a little wooden, but often, too, it is full of poetry and wisdom gorgeously expressed. In addition, Sileika elucidates the socio-political context of occupied Lithuania with astounding ease. He gives us a brilliant, highly accessible military history, one that remains largely repressed – underground – in the East and in the West.

Donna Bailey Nurse is a Toronto editor and writer and a frequent contributor to Globe Books.

Here are some review highlights:

How are we going to survive unless we turn our hearts to stone?” a comrade warns the hero of Antanas Sileika’s Underground. The question is an example of the elegant thinking that characterizes this rare and compelling chronicle … From its opening lines, the novel strikes a haunting note … This story picks up speed as it goes along, hurtling into the future and an unanticipated conclusion.

- Toronto Globe and Mail

Sileika’s novel is a gripping tale, and the fate of Lukas – how long his luck runs – engages the reader to the last page.

- National Post

Sileika writes with a spare style that suits the action sequences as well as the rare moments of tenderness or humour. Entertaining and sometimes shocking, the book describes a little-known period of European history that has been kept underground far too long.

- Montreal Gazette

Sileika vividly brings this little-known (to us) and very sad chapter of European history alive…..

- Toronto Star

… the drama is exciting, haunting and instructional in turn. It opens with an explosive scene of startling violence, moves through episodes of mounting tension and dread, and concludes in a kind of lyricism.

- Edmonton Journal

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

Eva Stachniak interviews Antanas Sileika

- Posted by - (1) Comment

Eva Stachniak is a Canadian and Polish novelist and short story writer. Her new novel "The Winter Palace" based on the life of Catherine the Great will be published in the fall of 2011. Her web site is: http://www.evastachniak.com

By Eva Stachniak

Antanas Sileika, a Canadian novelist and critic, a son of Lithuanian-born parents, is the author of two novels and one collection of linked short stories Buying on Time (nominated for both the City of Toronto Book Award and the Stephen Leacock Award for Humour). Underground, his newest novel, was published in March of 2011 by Thomas Allen. In the words of its publisher Underground “explores the narrow range of options open to men and women in desperate situations, when history crashes into personal desires and private life.” For me Underground is also one of the still rare Canadian novels which delve into the stories from behind the former Iron Curtain, a tempting topic of conversation with its author.

E.S. “Underground” begins with the poetic evocation of the borderline that “weaves around the middle of Europe.” How significant is this borderline for you, a Canadian writer with Lithuanian roots?

A.S.: The borderline at the center of Europe has been critical for me for most of my life. I felt for decades until the late eighties that I did not exist at all because I came from a place that did not exist at all.

In effect, there were two borderlines in Europe - first there were countries such as Poland and Hungary, which existed in the "other" Europe, and then there were places such as the Baltics or Ukraine which did not seem to exist at all. They were on no map of the time (unless the map displayed Soviet provinces). In my childhood, this was extremely confusing because my parents were filled with the melancholy of loss that their generation of refugees suffered from. Yet the site of their loss existed only in stories that they told, and these stories were a cross between fairy tales and the Aeneid, as if they had fled from burning Troy.

In my adolescence, I was embarrassed by my origins because I came from a pre-multicultural generation, one whose ethnicity was complicated by invisibility. But in my first year of university I underwent some kind of dramatic transformation and I refused to answer to the name "Tony", which I had used until then. Everyone had to call me "Antanas."

In my youth, the strongest resonance I ever found in my reading came from English translations of Czeslaw Milosz, whose Issa Valley and Native Realm I read and reread. Since the collapse of the Soviet Union, I have become more and more interested in the region that the historian Timothy Snyder calls, in his new book, Bloodlands. It's no accident that these bloodlands cover the approximate geography of the old Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth at its height.

I am fascinated about what Snyder, and others such as Norman Davies and the late Tony Judt have to say about this place, and I have discovered that the richness of stories I have at my disposal, rising out of my ability to read and speak Lithuanian, is huge. There is no other part of the world I want to write about any longer. A writer is somewhat merciless, and I can see that this region has had the most dramatic history in the twentieth century. What a source of material! And in the old days, no one in the West as interested, but now they are. Much remains to be told about the other side of Europe.

E.S.: From the Lithuanian perspective The Underground is a haunting tale of doomed love, tragic choices forced by history, and ultimate sacrifice. From the Canadian perspective it is also a story of a legacy that arrives at our doorstep and demands that we do something with it. Your publisher calls it and “untold story of the battle that continued long after Second World War.” When did you become aware of this particular “untold story” and how?

A.S.: Some of the early partisan material appeared long ago in the fifties, in particular the story of Juozas Luksa who fought, fled through Poland to Paris, married, and flew back into Lithuania with the help of the CIA in 1950, and was betrayed and killed in 1951. His story is the rough superstructure of my novel. But to be aware of a story is not the same as to know it.

The partisan story was complex and long, with boats sent in through the Baltic by the British, double-agents infiltrated into the movement, and many, many terrible personal stories, some of whose details I introduced into my novel. This information has only appeared over the last twenty years after the collapse of the Soviet Union, the opening of archives, and the publication of many memoirs. I learned, for example, that the Lithuanian equivalent of Dr. Seuss, a major children's writer named Kostas Kubilinskas, had betrayed and shot partisans because he wanted to ingratiate himself with the rulers. I think again of Czeslaw Milosz - Kubilinskas could have been a character out of Captive Mind. The particular grotesquerie of WW2 and afterwards is especially acute in the east, and this is a perspective I wanted to introduce here, in Canada, where we look at the war and postwar through a Churchillian framework of fighting the good war and winning it.

I am trying to enlarge our sense of that event and the postwar, to make more complex the good versus evil picture of stories such as Saving Private Ryan. I am trying to do something like showing the scene on the bridge at the beginning of the film, Katyn, in which you have civilians fleeing from two attackers. That event was something we were aware of in Canada before the film, but the film made us know it.

In America in particular, people are encouraged to think of their destinies as if they were masters of them, but Europe, and Eastern Europe in particular, teaches that your personal destiny exists at the whim of history, which might just as easily crush you as elevate you. That's a little pessimistic. Also, I have to admit that somewhat against my will, a certain theme of resurrection has crept in. Memory is a seed that may bloom again as a weed or a flower. Sometimes the dead do rise again, or if not the dead themselves, those who remember them.

E.S.:This is not your first novel that evokes the lands beyond the Iron Curtain. Woman in Bronze also dipped into the same well. Was writing of these two novels very different? And if yes, how so?

A.S.: One novel led to the next novel, but the story begins before that. In 1997, after I wrote a collection of stories called Buying on Time about immigrants in the Canadian suburbs, I realized I had found a method of writing about the twentieth century through a strange kind of window, Lithuania was far enough away to be remote - very remote from me in my everyday life - but dramatic things happened there as they happen everywhere in the world. And I had access to that world because I had some of the language (I read it and speak it passably well but cannot write it without many errors). I decided that if all the universe can be seen in a handful of dust, then I can deal with the twentieth century through a trilogy of works of fiction seen through my window into Lithuania. I know about that place, but I am not of that place. I am close and I am far.

The first book, as I mentioned, spoke of the suburban experience and the birth of consumer culture. The second, Woman in Bronze, attempted to speak to certain aspects of modernity. I was interested in how one creates morality in the absence of God, or how one creates a modern image that has moral weight, or seriousness within it. One has a choice in the twentieth century - does a modern artist create sensation and novelty, the golden calf that Moses finds when he comes down from the mountain, or does he create an icon in a different way, a symbol of a new reality, a new morality, or a new way of thinking?

There are also contradictions in modernity. I was struck that modern images were very often created by "primitive" people - Constantine Brancusi was the first to take sculpture into pure abstraction, and he used Romanian folk motifs to do it. Jazz dance came to us from the poor train conductor's daughter, Josephine Baker.

That describes the first two books - now let's move to Underground. If one is to speak of the twentieth century, one must speak of war. I struggled with this for a long time, trying to write war stories or holocaust stories. But none of this felt true to me - I was repeating what we already knew and had read about or seen in movies. Instead, I thought I would write about what we did not know, at least in the west: the war after the war, the grinding partisan war that dragged on for many years after the war ended in the west. And in all these three works I am comparing one life and another, measuring loss and gain.

E.S.: Toward the end of the novel Lukas and other characters are very bitter about being forgotten, swept under the carpet of post-war history. There are so many betrayals in the novel, including the hovering betrayal from Kim Philby and others like him. When I closed your novel I wanted to think about Luke Zolynas. I wanted to know what he makes out of this story of a half brother he now has to acknowledge. I wanted to know what impact this discovery will have on him… Can you speculate on this a bit, in the best tradition of gossiping on our characters???

A.S.: I think Luke Zolynas is a stand-in for me and others like me who only become aware of the past accidentally, because there are things in the past other generations have wanted to hide. In my own case, I stumbled across some family surprises while doing research for this novel. I discovered, dramatically, that one of my late uncles strangled his lover and threw her body down a drainage well in 1931, and then hoped to use acid to dissolve the body with material from a laboratory set up to make bombs to kill the Lithuanian president. Nobody had ever told me about this. He died in Chicago in 1952. As well, the photograph that was in the magazine article was not of my uncle, but, mistakenly, of my father. The historian told me it was my father's prison photo. Prison? My father never told me about that. It turns out he too was trying to overthrow the Lithuanian president (who came to power in a coup in 1926). The past holds all kinds of surprises, good and bad, but most of us walk over the past like barbarians walking over the ruins of Rome. On the other hand, you might consider the past a trap, and you might consider forgetting to be absolutely necessary for us to live out lives. Many Canadian writers despise historical novels. I think of Milan Kundera's Book of Laughter and Forgetting. Perhaps if you cannot forget, there can be no laughter.

But as for me, I have belonged to a transition generation. I was the only one of my three brothers born here, but I still feel as if I am the survivor of the shipwreck that was my parents' lives upended by WW2. I belong nowhere. My job is to consider my parents' past in Lithuania and my children's future here. Obsession with the past only leads to problems, but I cannot seem to let those problems go. Luke Zolynas will find his life become more complicated. He will find that the past as he understood it was sand, not stone. He will find this new information not so much redemptive as complicating, including a whole new set of relatives who will look upon him as the lucky one. But there will be some happiness too. He and his half brother survived because of the actions of their father, whose own life was tragic but whose children's lives became somewhat normal, even if one son was luckier than the other.

E.S.: This is a question I find very important, for I struggle with the same issue myself. You write in English while most of the events you write about happen in Lithuanian. You have to give your characters an English voice, English expressions. Since language always shapes the way you can tell a story what were some of your victories and some of your frustrations in this process?

A.S.: My difficulties with writing about Lithuania in English come in various ways. First comes the problem of ignorance of the place. I must tread very quickly and clearly over background information because English speakers who have no difficulty distinguishing Irish North and south, Scottish, English and Welsh and all the tensions among them cannot tell the difference among a Russian, Soviet, Byelorussian, Pole, Ukrainian, and Lithuanian, to name just a few. To them, all except Poles were Soviets and all Soviets were Russians. Most people I know think Prussians are types of Russians. Therefore I must compress very, very quickly and move the story forward. No professorial paragraphs on history are permitted. And yet I must give some background, so I tend to do it in a fairy-tale way. In my last book, I have paragraphs about a mythical "Rainy Land" and in this one the voice occasionally rises high to look at the Atlantic Charter or Yalta, but I hope to make that voice lyrical or ironic - certainly not professorial.

The next problem looks simple, but isn't, and that's the problem of Lithuanian names, in particular men's names, almost all of which end in –as: Antanas, Juozas, Kazimieras, Jonas, Petras, etc. This uniformity is boring, but I hate to make all the above into Anthony, Joseph, Kazimir, John, and Peter. Therefore I take an uneven approach. In this novel, Lukas is easily understandable to the English ear, although it was practically never used as a first name in Lithuanian. I stuck with the code name Lakstingala because I thought is sounded like something out of Lord of the Rings. Women's names are a little easier, but not much.

When it comes to atmosphere, I rely a lot on food, but Lithuanian food is very simple and not evocative to most people. In this book, I used black currant as the flavour of home - the flavour is mildly exotic here. My English tends to be as simple as possible in this novel. I don't like mixing in the odd foreign word, as they do in movies - ("Hey, tovarich, let's escape this camp together."). But diction is very hard to get right. No one can "scoot" in my novel, nor "take a hike", nor "beat it". It is very hard to comb out the modern turns of phrase and the particularly American ones and still sound fluid. One critic claimed my last novel sounded stiff, whereas I was trying to make the English limpid. Lithuanian is more romantic at times, more sentimental and by turns much rougher than English is. I need to "translate" this language into some semblance of English that sounds real, yet is not an imitation of English lords or Chicago gangsters speaking. It's a real struggle!

E.S.: There are also the complications of telling a story from an external, "other" point of view...the conflict between the romantic national myth and attempt to see a more universal story in it.

A.S.: The superstructure of my novel follows the true story of Juozas Luksa, who fought, went out to Paris, fell in love and married, and returned to fight for Lithuania, which he called, as a metaphor, his "first wife." This is the most romantic of Lithuanian true stories: the man who gave up peace to fight for his country. But when I came to the story, I realized we live in different times. We no longer believe in big causes as much as small ones. Therefore in my novel, Lukas goes back not to the metaphor of his first wife, but to his actual first wife. And before that, he went into the partisans not because of his patriotism but because of his useless, frightened brother, in order to protect him. It all becomes personal in my novel. Real Lithuanian patriots are going to hate me for this change to an iconic story.

As to the issue of complex stories, yes, modern stories are complex, and we realize that more clearly about the past now too. But there is a danger of revisionism through claims of complexity. One might say, for example, that a man died for his country because he had no life worth living and thus he identified with nation more than he should have. This is exactly the kind of thing Jews must worry about in further developments in thought about the Holocaust. The next thing you know, we'll be sympathizing with Nazis, and that would be a mistake. That would be a sort of revisionism. We should not vote in favour of complexity merely because it suits our times. On the other hand, in Marijampole, I spoke with a partisan museum director who said to me, "I know what you novelists do. You make everyone seem sympathetic. But please, do not make slayers into sympathetic characters. They are the ones who killed the partisans." But I could not follow his direction. The slayer who walks above the bunker where Elena is almost killed does not like his life and wishes he could do something else. He has been forced into becoming a slayer. I had to make him more complex than a simple enemy.

E.S.: In Polish literature Lukas’s generation was called the Columbus generation, those whose youth was shaped by WWII, the Nazis and the Soviets, the doomed battles, the breakdown of values they were brought up in. Bitter, tragic, they had to find humanity in a cruel, ruthless world filled with brutality and betrayal. What do they have to tell us that is still important?

A.S.: That generation can be further splintered into sub-groups. One of them includes many of the postwar partisans who only came of military age in 1944 -1948, meaning they were born in 1925 - 1929, too young to have acted during the war but old enough to have seen everything and been formed by it. I am incredibly impressed by those who fought because they were trying to push back in spite of the horrors they had seen. But I am more touched by the generations before them, the aspiring artists, engineers, teachers; the newlyweds, those expecting to retire and enjoy life, those who lived and loved in their circle of family and clan. They were like us because we have dreams too. But their dreams were destroyed by the crush of history on the aspirations of individuals.

We who live here, and especially those with not much Eastern European background, are easy moralizers about the past because we are either ignorant or we have not been tested. That generation is an example of what might happen to us under the same circumstances - some would be broken and some would survive. Some would be lucky and others not. We need to remember the indifference of history, which is a little like the elements that might sweep us away. We need a little humility. The good times always come to an end - war or drought, ecological disaster or disease. How will we face the next disaster?

One final lesson is the lesson of love. What impressed me were wives who waited years to reconnect with husbands, parents who searched for their children, men and women who went to hell to save the ones they cared for - all the small personal impulses during the apocalypse. Somehow love survived - not always, not undamaged, but sometimes.

As a child I remember long, boring afternoons at a shop on Roncesvalles where my mother had fabric measured out, filled out forms, and paid outrageous duty to make up packages for her relatives. She knew we were lucky. She was trying to do something to compensate for some of the bad luck that had fallen on the shoulders of the ones she loved.

E. S.: Thank you.

Eva Stachniak’s newest novel The Winter Palace, set at the court of Elizabeth Petrovna and Catherine the Great will be published by Doubleday (Canada) and Bantam Books (U.S.) in September of 2011.

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

The Lithuanian language – past, present, future

- Posted by - (9) Comment

Vin Karnila, Associate editor

vin.karnila@VilNews.com

There are many articles written about the Lithuanian language. Some of them focus on the Indo-European / Old Sanskrit origins of the language, some delve into the complexities of the language and some are written for the understanding of the linguists. What attracted my attention to this article was that this is one of the best articles I have come across that gives a clear and easy to understand report on how the Lithuanian language evolved into what it is today.

This article was written by Giedrius Subačius, who is a member of the Institute of the Lithuanian Language located in Vilnius. The Institute of the Lithuanian Language itself is something to take note of. The institute holds the high status of a state research institution of the Republic of Lithuania. It is the center for scientific research of the Lithuanian language. Currently it has over 100 employees with over 70 of them taking research positions.

The main activities of which are the following:

1. Lexicology, lexicography, and research into the grammatical structure of the Lithuanian language;

2. Research into the history and dialects of the Lithuanian language, and sociolinguistic research;

3. Research into the operation of the Lithuanian language in society, and into terminology;

4. Research into Lithuanian onomastics.

The main work of the Institute of the Lithuanian Language:

1. The preparation of the Dictionary of the Lithuanian Language (in 20 volumes) and its computerised version, the accumulation of a computerised database of the Lithuanian lexicon.

2. The preparation of the Dictionary of the Standard Lithuanian Language.

3. The compilation of an academic grammar of the Lithuanian language, research into the evolution of Lithuanian syntax.

4. The gathering of data on and research into Lithuanian dialects, the preparation of an atlas of European languages.

5. The evolution and development of the written Lithuanian language, and the compilation of a database of old Lithuanian writings.

6. The analysis of the development of the norms and terminology of the Lithuanian language, and the compilation of a database of linguistic phenomena and their assessment.

7. The preparation of an etymological dictionary of Lithuanian toponyms, and research into toponyms and personal names in Lithuania.

Quite impressive!!!

For more information about the Institute of the Lithuanian Language please visit

http://www.lki.lt/LKI_EN/

So now let us share with you this very interesting and informative article written by a person from an institution that is highly qualified in this subject.

The Lithuanian Language

By Giedrius Subačius

Due to their similar political situations 20th historical development in the 20th century, the three Baltic States - Estonia, Latvia and. Lithuania - are often treated as sisters, and referred to as Baltic countries. This name is even applied to the entire region. But professional linguists have always pointed out that this is not an appropriate designation. The term Balt was coined in the 19th century by the German linguist Ferdinand Nesselman to name one of the branches of the Indo-European languages spoken on the eastern shores of the Baltic Sea. Linguists had already known Indo-European groups such as Germanic, Romance and Slavic; now they discovered another group of Indo-European languages, the Baltic languages. Since then, in linguistics, the term has been applied only in reference to the true Baltic languages: the living Lithuanian and Latvian languages, and dead languages such as Curonian, Semigallian, Selonian, Yotvingian and Galindan. For the Balts, the early 13th century was when they emerged from oblivion to enter European history and become permanent participants in it. This was the time when the two German orders, the Teutonic and the Livonian Order, first appeared on the territories inhabited by the Balts and slowly settled in the areas of the old Prussian and Latvian tribes. It was the time when the pre-Christian Lithuanian state emerged, capable of defending itself against the militant neighbouring orders. The present-day Lithuanian nation was formed mainly from the Lithuanian and Samogitian tribes, but included Semigallians, Curonians, Sudovians and Yotvingians. The Lithuanian state, which emerged in the middle of the 13th century, has retained to this day these lands as the core of its territory, although the history of Lithuanianstatehood has been very volatile. In the 13th to the 16th centuries it stretched over large areas inhabited not only by Balts but also by Slavs. From the mid-16th century to the end of the 18th century it was in a union with Poland. From the end of the 18th century to the early 20th century the Russian Empire occupied it. From 1944 to 1990 it was occupied by the Soviet Union. Since 1990, Lithuania has again been a democratic independent republic, like Latvia and Estonia.

Lithuanians make up about 80 per cent of the population of Lithuania. This means that more than three million people (perhaps three and a half million) consider Lithuanian to be their mother tongue. It is spoken by the autochthon Lithuanian populations in some border areas of Poland and Belarus, and by numerous Lithuanian émigrés in other countries. The largest émigré groups are to be found in the United States.

People have long been curious to know what makes languages similar, and why people speak different languages in different countries. Linguistic similarity could be evidence of a tribal or national affinity, or even prove the place closest to God. For instance, during the Renaissance one similarity theory held that Lithuanian was simply a debased Latin, and we know that Latin was the most sacred language in the Catholic world. Genealogical studies of languages took on a scientific approach only in the 19th century. Traditionally, it was based on the history of sounds: that is, it was a history of the spoken language, which people learn in some mysterious way in early childhood without any apparent effort, as if the sounds of the language overwhelmed them like a swollen river.

Latvian is the only living language with sounds and endings similar to those of Lithuanian, but a Latvian and a Lithuanian who do not speak each other's tongue cannot communicate, unlike a Dane who can communicate with a Norwegian, an Italian who can communicate with a Spaniard, or a Ukrainian who can communicate with a Russian. A Lithuanian and a Latvian can only recognise a few words in each other's speech, and this is not enough to hold a conversation. Therefore, we can say that Lithuanian is a language that cannot be understood by a speaker of any other language who has not learnt it. More than that, even users of different Lithuanian dialects (such as Samogitians and Aukštaitians) cannot understand each other unless they communicate in standard Lithuanian, which they, have to learn.

Since the 19th century, when the similarity between Lithuanian and Sanskrit was discovered, Lithuanians have taken a particular pride in their mother tongue as the oldest living Indo-European language. To this day, to some Lithuanians their understanding of their nationality is based on their linguistic identity. It is no surprise then that they proudly quote the French linguist Antoine Meillet, who said, that anyone who wanted to hear old Indo-European should go and listen to a Lithuanian farmer. The 19th century maxim - the older the language the better - is still alive in Lithuania.

The history of sounds explains how the Lithuanian word sūnus and the German Sohn, English son, and Polish syn are not loanwords from one language to another, but have the same origin. The same is true of the Lithuanian duktė, German Tochter, English daughter, and Polish corka.

This genealogical history of sounds is like a biological science: tracing DNA sequences is like tracing and reconstructing sound sequences. Thus, we can say that throughout the centuries, the changes in Lithuanian "DNA sequences" have been less numerous than in other languages, and that is the reason why it is considered to be a very old language.

The social history of the Lithuanian language can be considered in the context of its relations and contacts with other languages. For a number of centuries, contacts were especially close with two living languages, German and Polish (in addition to Latin and the East Slavic written languages).

Lithuanian has come into contact also with Yiddish, Russian and other languages, but these contacts have left fewer traces.

Lithuanian culture in East Prussia was strongly influenced by German culture. From the 16th century until the middle of the 20th century, East Prussia produced a large number of Lithuanian books: translations of the Bible, psalm books, grammars, dictionaries and primers, including the first Lithuanian translation of the Bible (by Jonas Bretkūnas [Bretke] in around 1590-1602) and the first Lithuanian grammar (by Danielius Kleinas in 1653). In all of these activities, Lithuanian was in close contact with German. The first Lithuanian manuscript of the Bible was mostly a translation of Luther's translation; the second Lithuanian grammar was written and published in German (in 1654); a large number of psalms in the 16th century were translated from the German; and all or almost all of the bilingual dictionaries (there were no monolingual Lithuanian dictionaries) known since the 17th century were either German-Lithuanian or Lithuanian-German.

At the time that Lithuania formed a commonwealth (federation) with Poland (1569 to 1795) and when it was occupied by the Russian Empire (1795 to 1914), the Lithuanian language in Lithuania proper was under the influence of the Polish language. In the middle Ages, Lithuanian dukes and gentry spoke Lithuanian; but during the Renaissance they switched to Polish. Gradually, Polish became the language of culture. It is for this reason that nowadays Lithuanians sometimes take more pride in their, older dukes, who spoke Lithuanian, and cannot fully accept the later ones who could not. The dominance of the Polish language meant the introduction and use of Polish letters: the digraphs sz and cz for š is and č respectively in modern Lithuanian, and the letters 1, z, i and s.

At the end of the 19th century, however, neither of the two written traditions (Prussian or Polish) would form the foundations of modern standard Lithuanian. The national movement wanted to standardize the language in such a way that it would be different from other languages in the area. The Lithuanians rejected the Polish letter 1, refused, to accept the German and Polish w, and replaced cz and sz with the Czech č and š. In the end, standard Lithuanian became established in Lithuania; while in East Prussia the language has disappeared, together with German, to give way to Russian in the newly emerged Kaliningrad Region. Still, some elements of the writing from East Prussia were transferred into standard Lithuanian, such as the letter ė, the use of the letters i and y, and the majority of the case endings.

It is interesting that these letters became an, integral part of the spelling at the same time as the, Lithuanian (or Latin) letters were prohibited by the Russian authorities. The late development of standard Lithuanian has been responsible for some of its modern features. For instance, ą, ę, į, ų, ė, č, š, ž, ū are relatively new additions to the Latin alphabet.

Modern though they are, all these additions to the Latin alphabet are a nuisance to foreigners. These diacritical marks, or accents, to them are like background noise in a recording of music, or a spot of fat on a clean tablecloth: an unavoidable nuisance, to be ignored in order to avoid irritation. Foreigners have to study long and hard to understand why in Lithuanian dictionaries the word cinikas (a cynic) comes before čekistas (a Chekist).

Another problem is that with the advent of the Internet the old Latin alphabet, which has been preserved and used in almost its original form by the English language, is seen as the most modem alphabet.

It is true that, in the last few years, the developers of universal fonts, Internet browsers and e-mail programs have made great efforts to show more respect to these letters, to make them convenient to use and safe against discrimination in any way.

Lithuanians are always pleasantly surprised and glad to meet a foreigner who has learnt some of their language and is familiar with their special letters. It is gratifying to hear a foreigner speaking Lithuanian, because that is not a skill commonly found beyond the country's borders, and Lithuanian has never been widely taught as a foreign language.

To a person who is familiar with old Indo-European languages such as Latin or Ancient Greek, Lithuanian grammar will come more easily than to a person who can speak modem "English, Spanish, Italian, French or German. Due to the old features of Lithuanian grammar, most foreign students find it a very difficult language to learn. It is frustrating to have to learn five declensions, each with seven cases, both in the singular and the plural. The very concept of an ending is difficult to grasp if a person speaks only English. Some learners are frustrated by the mobile stress in different forms of the same word, which sometimes outwits even the native speakers.

On the other hand, the late development of standard Lithuanian offers certain advantages to learners of it. Even native speakers believe that the pronunciation is almost entirely consistent with the spelling: that is, that the words are pronounced exactly as they are spelt. One letter usually corresponds to one sound. In this respect, Lithuanian is more modern than French or English, where the same letters do not always represent the same sound.

Due to the structural peculiarities of their language, Lithuanians themselves experience various difficulties in learning other ones. For example, they find it difficult to master the use of articles in English, German, Italian, and French, because in Lithuanian there are none. The concept is rendered by other means, such as definite or indefinite adjectives: The White House is Baltieji Rūmai: The word order in a Lithuanian sentence is quite free, and is a convenient means to express a variety of nuances. Therefore, when learning English or German, Lithuanians are inclined to 'improve' the syntactic constructions of these languages by 'liberating' the word order.

Everybody knows that Lithuanian has a variety of colourful swearwords: for example, rupūžė! (toad), rupūs miltai! (coarse flour), kad tave sutrauktų) (I wish you were contracted). But when a Lithuanian is truly angry, a foreigner may be surprised to hear Russian or English swearwords escaping his lips. In the speech of town dwellers, probably the most popular Lithuanian swearword is velnias! (Devil), but in a Catholic country the reasons for its being a swearword should be evident.

In contrast to Soviet times, the Lithuanian Constitution stipulates that "the Lithuanian language is the official language of the Republic of Lithuania.” This means that it must be used in all areas of public life. The country has a National Commission for the Lithuanian Language, responsible for monitoring and correcting the use of it. It even has the right to impose fines for certain mistakes in public advertisements. On the other hand, efforts are still being made to preserve the languages of minorities, Russian, Polish, Belarusian, etc.

What do Lithuanians think is the future of their language? Some believe that with the disappearance of Soviet unifying policies, the area of use of the language has expanded and they are happy about this. They are also aware of the dangers posed to the survival of the language by the country's integration into Europe. On the other hand, the number of Lithuanians learning foreign languages is constantly increasing, because everybody understands that Lithuanian alone is not sufficient for effective communication in the world.

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

Coronation of King Mindaugas (Adomas Varnas, 1952 m.)

6 July is Lithuania’s State Day and a national holiday. On this day, Lithuanians honour the coronation of Mindaugas, who became the first and only king of a unified Lithuania in 1253.

By Tomas Venclova, historian