THE VOICE OF INTERNATIONAL LITHUANIA

|

VilNews has its own Google archive! Type a word in the above search box to find any article.

You can also follow us on Facebook. We have two different pages. Click to open and join.

|

Historical Lithuania

Best-selling author Ruta Sepetys interviewed by Ellen Cassedy

Ruta Sepetys’ novel “Between shades of Gray” tells the story of the Soviet deportations of 1941. More at www.betweenshadesofgray.com

June 14 marks the 70th anniversary of mass deportation of Lithuanians to Siberia. On this date in 1941, as Nazi Germany prepared to invade Lithuania, Soviet authorities loaded tens of thousands of people – men, women and children – into cattle cars and transported them into exile. Some were sentenced to death; some died under harsh conditions of forced labor; some survived. With Stalin’s death in 1953, the Siberian camps began to empty out. But it was many years before the stories of the exile were openly told.

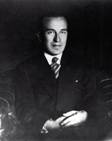

Author Ruta Sepetys

A new novel, Between Shades of Gray (Philomel/Penguin), brings the story of the 1941 deportations into vivid focus. It will be published in Lithuania under the name Tarp pilku debesu (Alma Littera), and in 23 other countries.

VilNews correspondent Ellen Cassedy interviewed author Ruta Sepetys Washington, D.C.

Growing up in America as the daughter of a Lithuanian refugee, you didn’t know that members of your own extended family were among the deported. How did you find out?

I visited Lithuania several years ago and met with some family members for the first time. They told me that after my grandfather left Lithuania in 1940 with his wife and son (my father), officials came looking for him. When they couldn’t find him, they deported other members of the family.

And once you learned what had happened…

I became passionate about telling the story. I went back to Lithuania and met with survivors, psychologists, historians, and government officials. Everyone I met had a connection to Siberia.

As a member of the second generation after the deportations, did you feel you had a special role to play?

Yes. I asked questions that the previous generation might find inappropriate. I wanted to get at the truth. I wanted to know.

Were these events difficult for people to talk about?

Sometimes, yes. At first I thought I would write the story as non-fiction, but people’s hands were trembling as they talked to me. “You can’t use my name,” they said. They wanted to talk, but not on the record. I wanted the story to be personal. I wanted characters that readers could root for, cry for. So I created Lina, the 15-year-old heroine of the book.

As the book opens, Lina is a lively teenage girl looking forward to summer vacation. Then the secret police arrive to take her and her mother and brother to Siberia. Lina’s efforts to survive in both body and soul make for a harrowing tale, but also, I found, an uplifting one.

What struck you about the survivors you met?

Their capacity for forgiveness. It seemed that those who suffered the worst found the most forgiveness. It was such a gift to meet with these people.

What does the title mean?

Over and over, survivors told me that what they went through was complex, not black and white. Not all of the NKVD officers were bad, for example. Some helped the prisoners with small acts of kindness, which made them feel human again and gave them strength.

Your book is winning great acclaim. You’re making two European tours. Why do you think people are open to hearing this story now, when in the past they might not have been?

People gravitate toward stories about the human spirit, about characters who are beautiful in their imperfection. Maybe people find something of themselves in these characters.

I hope we can use this story to study a tragic part of history and create more protection for the Baltics. Examining history creates hope for a more just future.

My own Jewish family suffered from the crimes of the Nazi era in Lithuania. How do you think the two eras should be examined today?

I think the crimes of Hitler and the crimes of Stalin should be studied and acknowledged separately, but I hope people will be open to conversations where both parts of history are examined and discussed respectfully. I hope we can celebrate our braveries and console our regrets together.

Last words?

For many years, Lithuania tried to get this story out there in the world, but our story was lost.

I wrote the book, but it’s not my story. The story belongs to Lithuania and the Baltics. I’m honored to tell it.

Read more about Between Shades of Gray at www.betweenshadesofgray.com.

|

Ellen Cassedy |

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

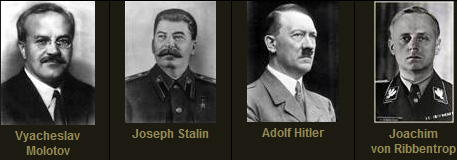

The Molotov – Ribbentrop Pact

- Posted by - (1) Comment

|

Part 1 of 2: |

THE MOLOTOV - RIBBENTROP PACT: THE DOCUMENTS

Dear Readers,

In this part 1 of 2 articles about the Molotov – Ribbentrop Pact and the Secret Protocols, you will get some insight as to when and why the Pact and Secret Protocols were made public and the work that has done to verify to authenticity of the copies of the documents now available.

INTRODUCTION by EDITOR SAULIUS SUŽIEDĖLIS

The day after the signing of the German-Soviet Nonaggression Pact of 23 August 1939, Soviet and German newspapers carried the news and text of the treaty to a stunned Europe. However, from the very beginning there was well-founded suspicion that the Pact contained more than met the eye. According to Richard Maasing, an officer in the Estonian general staff, the Estonian military had realized by 26 August that the Pact divided the Baltic States into German and Soviet spheres of interest and that Estonia had been assigned to the latter. It seems that the Latvian diplomatic service also learned of the contents of the Pact soon after the signing and that rumors about Germany turning over Latvia to Russia proliferated. Thus, while the exact contents of the secret protocol of 23 August and the subsequent secret arrangements of 28 September 1939 were unknown to the governments of the Baltic states, and knowledge of the texts was restricted to a small number of German and Soviet officials, the general outline of the agreements on "spheres of influence" was either known or strongly suspected very soon after they were concluded.

Moreover, despite the provisions on strict secrecy, Stalin and Molotov leaked the fact of their secret agreement with the Germans on the spheres of influence during negotiations with Baltic leaders in Moscow as part of the Soviet strategy of pressuring the Baltic governments into accepting the mutual defense pacts with the USSR. This is confirmed by a number of different sources, including the Lithuanian Foreign Minister Juozas Urbšys and Gen. Stasys Raštikis, the Commander of the Lithuanian Armed Forces during the negotiations in Moscow in early October 1939. The Soviets informed the Germans of their indiscretion; the leaks to the Baltic ministers irritated the Germans who clumsily attempted to diminish the importance of the secret Pact provisions in their replies to the astonished and perturbed Baltic representatives. It is inconceivable that news of the German-Soviet horsetrading concerning the Baltic States did not subsequently come to the attention of the Western powers.

The exact details of the secret territorial provisions of the German-Soviet Nonaggression Pact of 23 August 1939, the German-Soviet Boundaries and Friendship Treaty of 28 September, and the Secret Protocol of 10 January 1941 (concerning the so-called Suwalki Strip), were unknown until the appearance of copies of the secret protocols in the West after the Second World War. It came to the public's attention for the first time as a defense document in the Nuremberg Trials in 1946 and has since been quoted in numerous publications. The description of the secret protocol of 23 August 1939 in the Estonian-language CP daily Rahva Haal of 10 August 1988 (published a week later in Sovetskaya Estoniya) suggested that the original is held by the Foreign Ministry Archive of the German Federal Republic in Bonn. For his part, Valentin Falin, then head of TASS, reiterated at a Moscow press conference that no original of the secret protocol has ever been found.

In a strictly technical sense, Mr. Falin was right. According to American scholars who worked on the mammoth project of classifying and filming captured German records after the war, the originals of many of the most important documents of the Reich's Foreign Office (Auswaertigen Amt) were, in fact, never found. In 1943, as the archives of the German Foreign Office were being evacuated from Berlin because of the Allied air attacks, Reich Foreign Minister Joachim von Ribbentrop ordered the filming of the most important papers. The work was carried out by Paul Otto Schmidt, the chief interpreter of the Reich Foreign Office. Karl von Loesch, Schmidt's assistant, placed the films into boxes and buried them. Thus, these films survived the destruction of many important Foreign Office records carried out by the Nazis themselves at the close of the war. In late May 1945 Loesch met Lt. Col. R.C. Thomson, chief of the British documents team, and the so-called Loesch films became part of the Captured German Records project. The German-Russian treaties of 23 August 1939 and 28 September 1939, together with their secret protocols, were found in the films of Ribbentrop's working files. (These are contained in part of the series F1-F19 in the German Foreign Office collections).

Over the years, some East Bloc officials and scholars have either ignored the secret protocols of the German-Soviet treaties, or have presented them as Western forgeries. There are a number of reasons and circumstances that virtually eliminate the possibility that the secret protocols are fakes. As mentioned above, the existence of the protocols was revealed to Baltic statesmen in the autumn of 1939. The Germans, when confronted by indications that territorial arrangements had been worked out between the Reich and the Soviet Union, did not actually deny the existence of such agreements at the time. The behavior of both the Soviet and German governments during 1939-1941 indicates a basic understanding of each other's territorial prerogatives in Eastern Europe.

Of course, circumstantial evidence of the existence of an agreement does not address the possibility that understandings different from those described in the secret protocols had been undertaken. However, in addition to forensic testing of an actual original or authentic carbon copy, there are other ways of ascertaining the authenticity of a historic document. As medieval and early modern specialists know, few important historical documents have survived in the original. Often we deal with copies of copies made at a later date; sometimes, documents are excerpted in commentaries, that is, secondary works, and other texts written many years after the fact. In other words, we often learn about texts from references to them in other texts. Naturally, the situation is much better for the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Yet any overview of references to the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact contained in captured German correspondence makes the theory of a forgery extremely unlikely if downright impossible.

The number of references, partial quotes from, and allusions to the secret protocols in the available collections of diplomatic documents after the war is quite impressive. The various references can be grouped as follows:

(a) the preliminary diplomatic exchanges in July and August 1939 concerning German and Soviet diplomats;

(b) the correspondence between 23 August and the end of October 1939;

(c) the exchanges of views concerning the territorial changes of summer 1940 ending with Molotov's visit to Berlin in November 1940;

(d) the final period before the German attack on the Soviet Union, November 1940-June 1941. The evidence for the authenticity of the secret protocols is overwhelming, even if we ignored the memoir literature of the participants themselves.

The way in which the details of the various exchanges of correspondence concerning Poland, the Baltic States and Bessarabia, the territories explicitly named in the German-Soviet correspondence, dovetail with the provisions of the secret protocols, as well as with actual German and Soviet diplomacy, is striking. Any assumption that the secret protocols were a creation would lead to the conclusion that the hundreds of documents which refer to and quote the protocols would also have to be forgeries. That someone could succeed in such a task strains credibility. No forgerer will go out of his way to make a task unnecessarily complicated by increasing the number of factual variables, thus risking exposure. Certainly any creator of these numerous "supporting" documents would have to be aware of the probability that Soviet archives would contain records conflicting with the accounts of events contained in supposedly forged correspondence of the German Foreign Office.

It is important to remember that there is an immense difference between (a) documenting a nonexistent event or communication for propaganda purposes, a well-known disinformation stratagem, and (b) structuring a forged document, which distorts an otherwise real event in the more distant past, involving real personalities interacting within a complex bureaucracy. The first type of fabrication is relatively simple and risk-free; it normally requires the creation of only a single document and is a "one-shot" operation. From the forgerer's point of view, the fictitious event cannot be, and need not be, proven or disproven. It can always be affirmed as long as there are those willing to believe the lie.

However, the second type of creation is enormously difficult and, in fact, quite risky for the forger. The danger of discovery is particularly acute if the event in question, such as the negotiation and conclusion of the German-Soviet Nonaggression Pact, is some distance in the past and well-documented by voluminous primary sources. Physical expertise in document creation is of limited help here. Total control over all sources of documentation of the broader historical event in question is the only way to assure success in fabrication. Everything must fit perfectly; every additional fiction necessary to construct the lie considerably increases the number of variables to be taken into account and compounds the risk of detection. The fabricated structure must correspond exactly to the past, both the known and the yet-to-be-discovered. It must fit precisely within the continuum of historical time. The enterprise requires a domination of the past and present as thorough as that envisioned in Orwell's 1984. In real life, particularly in situations where documentation is abundant and scattered among different jurisdictions, this sort of total control over the sources is virtually impossible to achieve.

The fact is that none of the numerous supporting documents which confirm the existence of the secret protocols has been seriously questioned by competent scholars in the West. There seems little reason to doubt the authenticity of the texts of the secret protocols that partitioned Eastern Europe between Germany and the Soviet Union in 1939. However, even the hint of doubt could finally be laid to rest should the Soviet Union provide access to its archives on the 1939-1941 period for credible and independent scholars. There would be no lack of expert help in finding the important documents assuming they are still extant. As one of Lithuania's leading and most popular poets, Justinas Marcinkevičius, told the 23 August 1988 demonstration in Vilnius on the anniversary of the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact:

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

And so, these days Moscow's scholars have once again announced in the press that they still cannot, are unable, to find these (secret) protocols in Soviet archives. This is a joke, nothing else. It is entirely clear that Moscow does not locate that which it does not want to find, that which is unnecessary to find. One can search, but one doesn't need to find. I say, perhaps, Baltic historians and archivists could help them (in Moscow). This would truly constitute unselfish fraternal assistance for the sake of historical truth.

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

In part 2 of 2 of this series you will see the microfilm copies of the German-Soviet pacts housed in the National Archives in Washington, D.C. and the German and Russian-language facsimiles of the German-Soviet Nonaggression Pact of 23 August 1939 and the Secret Supplementary Protocol.

We would like to thank Lituanus for their kind permission to share this article with you.

LITUANUS

LITHUANIAN QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES

Volume 35 - Spring 1989

Editor of this issue: Saulius Sužiedėlis

THE MOLOTOV - RIBBENTROP PACT: THE DOCUMENTS

http://www.lituanus.org

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

Bloodlands – Europe between Hitler and Stalin

- Posted by - (1) Comment

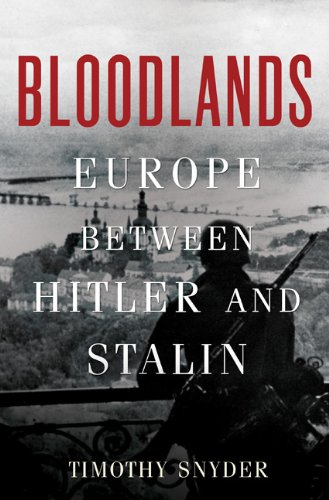

A book by history professor Anthony Snyder of Yale University

Hitler vs. Stalin: Who Killed More?

Who was worse, Hitler or Stalin?

Were these people victims of Stalin or of Hitler? Or both?

“Bloodlands makes clear that, if it hadn’t been for Hitler’s treachery in the spring of 1941, Stalin would have gladly remained a German ally. And it was not Germany alone that started the Second World War but Germany and the Soviets together, when they jointly invaded Poland, allowing the Nazis to finally catch up with a killing enterprise Stalin had already begun.”

- Charles Lewis, National Post, Canada

BLOODLANDS

Hitler vs. Stalin: Who Killed More?

Who was worse, Hitler or Stalin?

Were these people victims of Stalin or of Hitler? Or both?

A book by history professor, Anthony Snyder of Yale University has been brought to our attention and we think that the prospective this book gives on the enormous and tragic loss of life in Europe at the hands of Hitler and Stalin will be of interest to many of our readers.

Probably the best way to get you familiar with the book “BLOODLANDS” is to share with you some of the reviews.

To start with, here is a review by the author, Timothy Snyder, that appeared in THE NEW YORK REVIEW OF BOOKS.

http://www.nybooks.com/articles/archives/2011/mar/10/hitler-vs-stalin-who-killed-more/

He starts his review with the question - Hitler vs. Stalin: Who Killed More?

And ends his review with this question - Who was worse, Hitler or Stalin?

Were these people victims of Stalin or of Hitler? Or both?

Another review that appeared in THE NEW YORK REVIEW OF BOOKS is by Anne Applebaum. The review is titled - The Worst of the Madness

http://www.nybooks.com/articles/archives/2010/nov/11/worst-madness/?pagination=false

In her review she writes this comment:

“Snyder’s ambition is to persuade the West—and the rest of the world—to see the war in a broader perspective. He does so by disputing popular assumptions about victims, death tolls, and killing methods—of which more in a moment—but above all about dates and geography. The title of this book, Bloodlands, is not a metaphor. Snyder’s “bloodlands,” which others have called “borderlands,” run from Poznan in the West to Smolensk in the East, encompassing modern Poland, the Baltic states, Ukraine, Belarus, and the edge of western Russia. This is the region that experienced not one but two—and sometimes three—wartime occupations. This is also the region that suffered the most casualties and endured the worst physical destruction.”

From The New York Times Sunday Book Review is this review by Joshua Rubenstein who is the Northeast regional director of Amnesty International USA and a co-editor of “The Unknown Black Book: The Holocaust in the German-Occupied Soviet Territories.”

http://www.nytimes.com/2010/11/28/books/review/Rubenstein-t.html

His review which is titled “Europe Between Hitler and Stalin” begins with this statement:

“For most Americans, who remember World War II as beginning in 1941, it is necessary to recall that Europe had succumbed to an infatuation with violence long before the United States entered the conflict. Timothy Snyder, a professor of history at Yale, compels us to look squarely at the full range of destruction committed first by Stalin’s regime and then by Hitler’s Reich. Each fashioned a terrifying orgy of deliberate mass killing.”

And another review from Canada’s National Post’s, THEAFTERWORD literary section by Charles Lewis

http://arts.nationalpost.com/2011/01/28/bloodlands/

In his review Mr. Lewis writes:

“Bloodlands makes clear that, if it hadn’t been for Hitler’s treachery in the spring of 1941, Stalin would have gladly remained a German ally. And it was not Germany alone that started the Second World War but Germany and the Soviets together, when they jointly invaded Poland, allowing the Nazis to finally catch up with a killing enterprise Stalin had already begun.”

From the reviews you can see that this book is worth investigating. Professor Snyder casts a new perspective on the events of this period in this part of Europe. Another prospective is that this may be the first time that the total of all the tragic deaths of this period have been put in one book.

Vin Karnila, Associate Editor

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - (0) Comment

The Lithuanian partisan war 1944 – 1953:

A mistake to confuse resistance to occupation and WWII

The Second World War in Europe was a war fought against fascism – in particular the German variant exemplified by Nazism – and including also Italian fascism. The Second World War in Europe ended with the surrender of Germany; a surrender to which Russia was the major contributor because Germany was largely defeated at Stalingrad and Kursk and was always in retreat afterwards.

The Resistance in Lithuania against Soviet occupation was a heroic effort by some Lithuanians to obtain freedom for their country. In my opinion it is a mistake to confuse resistance to occupation and the Second World War. After the end of the Second World War there have been many occupations of many countries by Capitalist and Communist powers and each side has tried to characterise any resistance to its forces as an act of the 'Other' side.

Resistance to Occupation has a very long and courageous history in Europe and throughout the world and no 'side' has a right to claim the heroic activities of resistance fighters/activists to support its ideology. Inevitably that requires misrepresentation of the motives and objectives of the resistance; part of the theme of the book "The Ugly American" about the then developing Vietnamese war. It is also the type of misrepresentation that leads to one 'side' claiming "We are all Georgians now".

This misrepresentation is a major cause of the inability of 'Western' countries to think in any clear way about the activities grouped under the label of 'terrorism' and it is better to avoid such ideologically driven commentary/analysis.

Robert Jennings,

Ireland-Lithuania

The ‘war against fascism’ was a construct intended to make the Soviet Union look good

Antantas Sileika

Dear Editor,

Mr. Robert Jennings's letter, in which he claims that the Second World War was a war against fascism and nothing else, obfuscates the truth rather than clarifies it.

No one declared war on fascism. If they had, Spain and Portugal would have between attacked. The United Sates and other powers declared war against the axis powers. The "war against fascism" was a construct intended to make the Soviet Union look good and to disguise its own crimes. How was the Soviet invasion of Finland in 1939 a war against fascism? What about the forced incorporation of the Baltic States into the Soviet Union well before any war with Germany? What about the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact, which divided Eastern Europe between the Soviet Union and Germany? Would the Poles agree that the war was a war against fascism? Was the murder of the Polish officers at Katyn part of the war against fascism?

Neither Tony Judt nor Norman Davies, prominent historians of Europe, would agree that the conflict which only ended in 1989 with the fall of the Berlin wall was a "war against fascism."

Who benefits by such a formulation? Only the Soviets, whose crimes become excusable excesses of war. The independent Lithuanian government now considers the last anti-Soviet partisan commander, Jonas Zemaitis, to have been the Lithuanian head of state. It seems that L Beria considered him the same way because upon his capture in 1953, Zemaitis was transported to Moscow and interviewed by Beria who seemed to be seeking accommodation now that Stalin had died. However, both Zemaitis and Beria were executed that same year.

WW2 is remembered as a "good war", but this is a formulation that works only on the western side, where the allies came to help brave resisters such as the French underground. There were brave underground resisters in the East too, but no one ever came to help them. They fought until the dies, were captured, or gave up. Their story is just coming out now.

Antanas Sileika,

Canada

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - (0) Comment

Lithuania and the Soviet Union

1939 – 1940 (1 – 4)

Dear readers,

On 15 June 1940, Soviet Russia invaded Lithuania. This was the beginning of Lithuania's loss of freedom for more than fifty years and the beginning of one of the saddest and most tragic parts of Lithuania's history. There has been much talk and speculation about how this invasion came about and what Lithuania did, or as some would accuse didn't do, to prevent it. To shed clear light on this topic, we would like to share with you parts of the personal memoirs of Juozas Urbšys who was a member of the group that personally met with Vyacheslav Molotov and Stalin. After reading these fascinating and very informative memoirs we are sure you will have a better appreciation for the precarious situation the leaders of the then free Republic of Lithuania were in and what they did to try to protect the lives of the Lithuanian people.

|

|

|

|

|

We share these memoirs in 4 parts. Here they are:

(click on the titles to open the articles)

Part 1: In Moscow

Part 2: Vilnius, army garrisons

Part 3: We accustom ourselves to army bases.

Part 4: Ultimatum. Occupation.

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

Venclova`s Vilnius (1 – 4)

- Posted by - (0) Comment

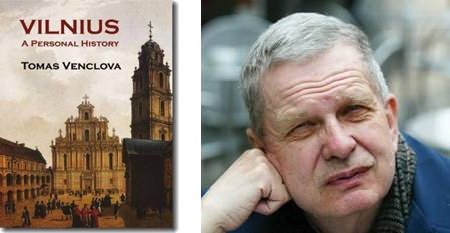

The history of the amazing Lithuanian city written by the great poet most qualified to write about it. This book includes a dialogue between the author and Nobel Prize laureate Czeslaw Milosz about the city. An absolutely indispensable work on the city that produced John Gielgud, Bernard Berenson and the Budapest String Quartet.

This is the four parts in a series of excerpts from Tomas Venclova’s book “Vilnius a Personal History”.

(click on the titles to open the articles)

Part 1: Venclova’s Vilnius

Part 2: Mindaugas, Gediminas and Vilnius

Part 3: Pagan Lithuania

Part 4: Lithuanians, “The Saracens of the North”

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

A Christmas story from Šilagalis, year 1945

- Posted by - (4) Comment

Desecrated bodies of unrecognized Lithuanian partisans.

By Aage Myhre

Christmas 1945 was in most of the world celebrated with a joy and delight hardly ever seen before. Young and old met in homes, on streets and in churches. An infinite series of victory events took place in almost every corner of the world. With a deep sense of joy and gratitude all wished each other a heartfelt good and restful Christmas holiday, knowing that the Nazi-era was over and that the world now more than ever could look forward to a future of peace and prosperity. The war had finally released its grip, forgotten was the economic recession of the 1930s, but forgotten was also our close friends and neighbours - the Baltic States.

On a small farm in northern Lithuania, in the outskirts of the village Šilagalis, the Christmas of 1945 is also approaching. It is the 22nd December today, and the mother in the house feels very happy that her 21-year-old son Povilas finally has come home for a visit after having been away for many months.

He has come to change to dry clothes that can keep him warm through the cold winter days waiting. His mother is infinitely happy to have her son home this one day, and she does everything she can to treat him with all the good food and drink found in the farm stores. You never know how long it will be till next time.

Povilas had joined a local partisan group earlier in 1945, and now spends all the time in Northern Lithuania's forests where the local "forest brothers" have established their hidden habitats. It is from these caches, often at night time, they still conduct operations against the military facilities and forces of the Soviet Red Army and the NKVD, the Soviet secret police which later changed its name to KGB. Soviet occupation of Lithuania has lasted more than a year now, but Povilas and other forest brothers still hope their constant needle can get Joseph Stalin to withdraw his troops out of Lithuania and the other two Baltic countries.

Povilas is glad to finally have gotten a day off, not least to be able to eat real Christmas food and experience a little Christmas fun with the family. A small nick in the pleasure it is that his father and his little sister and little brother are not home. Both the brother and the sister go to boarding school in the nearest city, Panevezys, and his father had in the early morning of that day gone into town to bring them home for Christmas. But his mother is here, and when she and he, with the arms around each other, go out to the barn to feed the animals, he sings joyfully a song stanzas he so often has sung in the partisan camp over the last months: "To die young is difficult, but not for my country. For my native country Lithuania I am ready to sacrifice my young life."

The mother scolds him motherly strictly that he sings: "You know it is not appropriate to sing now that it's Advent." Lithuania's Roman Catholic Church is quite strict when it comes to how to behave through the year's various festivals, and his mother reprimands therefore her son while at the same time she feels proud and glad that he does such an honourable service for the home country.

Back in the farmhouse they suddenly hear the dog starts to bark, and through the window, they see that a group of soldiers approaching. The soldiers are still in some distance, so Povilas has time to hide in a small cellar room they have beneath the living room floor, and the mother has time to hide the cellar hatch as best she can. This basement room has also previously been used to hide partisans, and both believe this is a safe hiding place until the soldiers have left again.

The mother goes out into the yard to meet the soldiers from the Soviet Red Army. They ask about her son is home and if he, in case, is alone. Without waiting for an answer they storm into the house and begin turning upside down all furniture and interiors. Then they begin to shoot down to the floor to see if there may be cavities under the floorboards. It takes some time before they discover the basement hatch, but as soon as they find and can open it, they fire a machine gun burst into the hole. Then it does not take long before they can take the now perforate and lifeless body of Povilas out of the basement. The whole operation has taken them five hours, but they have found what they sought, and another young Lithuanian life has been lost in the desperate struggle against the Soviet over power.

The distance from the farm to the road is over 500 meters, so the soldiers find a chain in the barn so they can tow the corpse of Povilas over the fields to the military vehicles that are waiting. The mother is forced to follow, and soon they are on their way to the NKVD headquarters in Panevezys where the body of Povilas is thrown out in the middle of the courtyard while his mother is brought to a prison cell in the basement.

Early next morning, little Christmas Eve 1945, the mother is brutally dragged up from the wooden bench she lay sleepless on during the night. Today, and each subsequent day through two weeks, she is brought up for interrogation, through the courtyard where her son's mangled body still lies. Christmas and New Year holiday season in 1945 passes by with this terrible routine of a mother dissolved into tears and sorrow, but early January she is released and can finally go home and tell the family what had happened.

In thousands of homes around the world families walk happily around their Christmas trees. They celebrate that Jesus is born and once again has overcome the world's evil. In northern Lithuania the parents of Povilas and other parents of killed partisans find that the bodies of their young sons have been dumped in a forest outside the village Kaizerlingas. During the dark night hours of the early January days 1946, they manage to find the dead bodies of their children and carry them home to secret burials in their hometown cemeteries.

Christmas 1945 is over. Most of the world looks forward to many good years of peace, freedom and economic growth. The Baltic States' ten year long guerrilla war against the occupants has barely begun.

The story of Povilas is real. It is based on a passage from the book "Lithuania's struggle for freedom" (Lithuanian Partisans' War Chronicles).

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

for Inga R

Madrid, 1799.

I must set sail before Napoleon tries to conquer London, winter has been hard in Madrid. From the beginning of spring I have enlisted as first gunner on a pirate ship. An old friend, a German Captain, has given me a map and a letter for some gentlemen in Memel. I have been serving among men of his Majesty Charles III. A betrayal has put my name among his enemies. In truth, my goal is to keep track of a beautiful woman, who seems an honest person. I've known her just by sight and hearsay, in the famous Klaipėda Castle during a trip by this port with English traders. She was discussing with master control, even too highly educated for my sword. She is a port that I don’t know. Her eyes guide me, but also betray me. In a few centuries my children will be writing about this feat. Useless for history; perhaps even bloody. This is my logbook. The rest should be decided by the fury of the wind, my trusty sword and the unpredictable night. First of all, I must learn her language to smell her tracks in her own Russian language. I do not know if one day I will find her. I just know that she lives near the Baltic Sea. There are Only a few students in these terms that they don’t know my search. Her eyes must find my voice. Now, I have just a face, a name, and I have seen that her eyes have strayed a dagger. Her words have founded that night in Memel more roads in my mind than all my adventures on the seas; even the women were silent, and her hands were distracting their humiliated eyes between adolescent flushes.

I have inherited this letter from my grandparents, it is a family treasure found at the bottom of a trunk by our ancestors. History tells us that he found her.

Klaipėda, 2011.

by Enrique Ferrer-Corredor

Enrique Ferrer Corredor is a Colombo-Venezuelan author and professor with a great academic background, has worked for William & Mary College and Hampton University in USA (currently he lives in USA, Virginia). He divides his time between literature, economics, political science and his love for soccer. He received an MA in Linguistics and Literature (Col) and a PhD in linguistics (Spain). He has been a professor also in other universities in Colombia as Universidad Externado, Universidad Pedagógica Nacional and Escuela Nacional de Ingeniería. He taught the Latin American poetry chair at the Instituto Caro y Cuervo. With "The Other Death of Salazar" he won second place in the the City of Florence's short story contest. He is co-founder of Común Presencia (literary Magazine) and, founder and director of Papeles (Papers); he belonged to many writers' workshops in Colombia and Venezuela. Ash of Moon, his first collection of poems, was published in 1994 and had two editions in 1998. In 2006, he published his book El público en escena (short stories). Also he has published many articles of literature and political science in international magazines. Today he is part of Word4word, a group of writers in Newport News, Virginia (USA).

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

Searching for the Holy Grail? Come to Vilnius!

- Posted by - (14) Comment

|

|

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

Hitherto unknown Da Vinci painting uncovered; the cousin of Lithuania’s Grand Duchess Bona Sforza

- Posted by - (7) Comment

|

The painting was thought to be an obscure 19th Century work known as Young Girl in Profile in Renaissance Dress. It has been revealed, though, to be a hitherto unknown work by Leonardo da Vinci and has been renamed La Bella Principessa. The painting became known when it showed up in a Christies auction house catalogue in the early 1990s. It sold for $19,000 to an art dealer named Kate Ganz, who subsequently sold it for a similar price in 2007. The work is now in a Swiss bank vault and is valued at $160 million. Peter Silverman, an art collector, was the first to suspect that the work was not 19th Century. After study, Silverman concluded that the painting was a hitherto unknown work of Leonardo da Vinci, one of the most famous artists of the Renaissance. Further study using the latest in digital imaging technology discovered a partial hand print and a fingerprint that matched those found on two other known works by Leonardo da Vinci. Finally Da Vinci expert Martin Kemp, Professor Emeritus at Oxford University, was called in to examine the painting, Kemp concluded that the painting was indeed a Da Vinci, likely dating from 1496. The work was executed on vellum and was meant to be the cover of a book of poetry, meant as a gift. Kemp believes that the portrait is of Bianca Sforza, daughter of Ludovico Sforza, Duke of Milan and his mistress Bernardina de Corradis. Hence Martin Kemp has renamed the painting, La Bella Principessa. |

|

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

Dr. Jonas Sliupas (1861 – 1944) with family and friends at his Palanga home in the 1930s.

Dr. Sliupas was a physician, publicist, and a leading nationalist liberal activist both in USA and Lithuania. He was Mayor of Palanga from 1933 to 1940, and returned to this office briefly during the Nazi occupation of 1941, until ousted because of his protest against the destruction of Lithuanian and Jewish lives. Dr. Sliupas was one of the interwar's leading politicians and advocates for a free, independent, honourable and prosperous Lithuania – a proud representative of the national patriarchs who continuously fought for Lithuania’s case through all the years between the First and Second World War. Dr. Sliupas continued to speak the case of a free Lithuania until his death in 1944. He will be celebrated as one of Lithuania’s true heroes and finest gentlemen ever, with an amazing record of achievements for his beloved homeland.

|

Please also read the attached article ‘Dr. Jonas Sliupas – Patriot of two continents’ (it’s in two parts) that appeared in the US publication ‘Lithuanian Heritages’ in 1995. |

Jonas Sliupas was born in Rakandžiai, County of Šiauliai, the 6th of March 1861. His uncle, Fr. Aloyzas Šliūpas, helped finance his early schooling. He studied history, philology and law at the University of Moscow from 1880 to 1881 and natural sciences at St. Petersburg in 1882. His student radicalism earned him three months imprisonment and a ban on further studies at any Russian university. Briefly, he edited the Prussian-based monthly Auszra [Dawn], the voice of the infant nationalist movement and was expelled by Prussian authorities.

His brother Rokas (1865-1959) became a famous activist-physician in the homeland, while his daughter Aldona (1886-1980) practiced medicine in the United States. Brothers Rokas and Silvestras (1859-1911) engaged in book smuggling during the tsarist ban of 1864-1904.

He came to the United States in 1884, where, subsidized by clergy, he entered the University of Maryland Medical School and became a physician in 1891, setting up private practice in the anthracite district of Pennsylvania. He was to remain there for thirty-five years, constantly on the lecture circuit, clearly establishing himself as the "father" of socialism and freethinking among his ethnic brothers and sisters.

As one of the few émigré intellectuals, the idealist elicited little support for his periodicals. Of his five publications, Laisvoji mintis [Free Thought] survived the longest, 1910-1915. His writings were simply too sophisticated for the masses.

In his essays, he professed socialist and freethinking ideas, combined with a vigorous ethnic spirit. At the same time, he belittled religion and capitalism as the twin enemies of the people. Curious to note, he enjoyed a fleeting friendship with Fr. Aleksandras Burba through a mutual passion for Lithuanianism and momentarily consorted with Polish radicals, such as the religious separatist Fr. Franciszek Hodur, to further mutual goals. Briefly, he headed the Lithuanian Freethinkers Alliance and held posts in other agnostic associations. The strong-headed maverick easily lost patience with those with whom he disagreed. For example, he parted company with Juozas O. Sirvydas, considered a major organizer of Lithuanian socialists. Šliūpas constantly engaged in polemics with clergy and in the homes of churchgoers, the physician's name became a household word.

Yet Šliūpas generated awe among his opponents. One finds him in the thick of nationalist stirrings, with membership on a variety of committees during World War One. In 1919, he assisted in setting up a Lithuanian mission in London and was a delegate to the Paris Conference.

Except for a fund-raising visit to the United States in 1920, Šliūpas was back in his homeland from 1919. One finds the restless scholar teaching high school at Biržai and Šiauliai (1921-1923), directing the Society for Ethical Culture (1923-1924) and teaching medicine at the University of Kaunas (1925-1930) where he was granted honorary doctorates in medicine, humanities and law. From 1933 to 1940, he served as mayor of the famed oceanside resort city of Palanga. He returned to this office briefly during the Nazi occupation of 1941, until ousted because of his protest against the destruction of Lithuanian and Jewish lives.

Šliūpas revived his Laisvoji mintis from 1933 to 1941 as a pulpit for his secularism, advocating a separation of church and state that would entail, for example, a civil registry of vital statistics, non-denominational cemeteries and the exclusion of religion from public schools.

The doctor was a prolific writer, publishing in Polish, German and English, as well as Lithuanian. He also borrowed, improvised and translated. The majority of his works trumpeted materialist and atheistic concepts, reflecting the nineteenth-century rationalism with which he was imbued. Another segment of his writings centered on Lithuanian history, culture and literature. His Lietuviškieji raštai ir raštininkai (Lithuanian Literature and Its Authors) of 1890, was the first attempt at survey. He delved into history with his substantial two-volume work, Lietuvių tauta senovėje ir šiandien (The Lithuanian Nation in the Past and Present) 1904-1905. One of his few English titles dates from 1918, called Essays on the Past, Present, and Future of Lithuania. Reflecting his own profession, he published Higiena [Hygiene] in 1928, and Senovės ir viduramžių medicinos istorija [History of Ancient and Medieval Medicine] in 1934.

An intimidating task awaits a biographer of this complex, bearded, bespectacled, tall and imposing figure, who won a small circle of allies and numerous enemies during his provocative career. Recognized by the Lithuanian government with the Order of Gediminas in 1936, Sliupas died in Berlin, Germany, the 6th of November 1944.

Source: LITUANUS

LITHUANIAN QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES

Volume 48, No.1 - Spring 2002

Editor of this issue: Violeta Kelertas

Jonas Šliupas Memorial Homestead at Vytauto g. 23a, Palanga,

stands there still today. Worth a visit!

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

The man who declined the presidency

- Posted by - (4) Comment

Dr. Jonas Sliupas (1861 – 1944)

The year is 1926. It is a very dark late autumn evening in Kaunas, Lithuania's capital between 1st and 2nd World Wars, when three officers from the Lithuanian army rush up to the house where Dr. Jonas Sliupas now lives while he teaches at the University of Kaunas. It is nearly midnight when the officers knock heavily on his door and asks to come inside.

The officers bring shocking news. They tell that since the early autumn of 1926 key officers within two army groups have been in full swing of planning a coup d’état in Lithuania, and that they have now reached the point that they want to depose of President Kazys Grinius and insert a new President. The question to Dr. Sliupas is therefore whether he can accept becoming the country's new President.

But Dr. Sliupas is not willing to accept. President Grinius has been his good friend for many years, and Sliupas is puzzled as to why the military has found a coup appropriate and necessary. His answer to the officers is therefore that the only way he could accept becoming President of Lithuania would be through a democratic election.

The officers had to leave Sliupas empty-handed that night, but continued their plans, and the very coup took place a few days later, during the very night when the 60th birthday of President Grinius was celebrated, 17 December 1926.

During that night, military forces occupied central military and government offices and arrested officials. Colonel Kazys Škirpa, who had initiated a military reform programme tried to rally troops against the coup, but was soon overpowered and arrested. The Seimas (Parliament) was dispersed and President Grinius was placed under house arrest at the same time as army colonel Povilas Plechavičius was declared dictator of Lithuania just minutes after he had been released from the prison cell where he was serving a 20-day sentence for a fist fight with another officer.

Later that same day, however, Colonel Plechavičius asked Antanas Smetona to become the new President of Lithuania.

The 1926 Lithuanian coup d'état (Lithuanian: 1926-ųjų perversmas) was a military coup that resulted in the replacement of the democratically elected government with a conservative authoritarian government led by Antanas Smetona.

|

|

TO THE PUBLIC

Lithuanian army, which sacrificed lives for dear Lithuania and is still ready to spill blood for its independence, seeing that the current Seimas and government are selling Lithuania to Bolsheviks and foreigners decided to temporarily take the power in its hands so that the power could be transferred as soon as possible to real sons of Lithuania. MARTIAL LAW IS DECLARED IN THE ENTIRE COUNTRY, and siege law in KAUNAS. Everybody is commanded to go about their duties; those who will not do their duties will be tried in military tribunal.

TEMPORARY WAR GOVERNMENT

|

|

A pamphlet distributed in Kaunas following the coup declared martial law and commanded everyone to go about their daily duties. It was signed by the Temporary War Government.

|

|

One can rightly ask what kind of Lithuania we would have had if Dr. Jonas Sliupas had not declined the Presidency that late autumn night. But in view of his human qualities and his extraordinary life story from both the United States and Lithuania, it is no wonder that this honourable man declined the Presidency and instead chose to continue his tireless fight for his beloved homeland, with important titles and tasks in the years leading up to World War II, but not as the country's top figure as the country's military leaders had wanted.

During his remarkably productive lifetime, Jonas Sliupas was a medical doctor, a leader of Lithuania's national awakening, a powerful orator and organizer, a writer of numerous articles on Lithuanian politics, economy, culture, and medicine, a historian, a diplomat, a free-thinker, and a publisher of seven newspapers. He also served as the author or translator of over 70 books and was a pioneer in helping develop and modernize Lithuania's economy.

Jonas Sliupas was born on the 6th of March 1861 in the village of Rakandziai in northern Lithuania. In 1880, he graduated with honours from Mintauja (Jelgava) high school. Next, he studied philology and law at Moscow University and later transferred to Saint Petersburg University to study natural science. Because of his participation in the student anti-czarist movement, however, Sliupas was incarcerated in 1883 and was banned from further studies at any Russian university.

The Russian government banned all books and newspapers in the Latin alphabet in Lithuania from 1864 to 1904. Consequently, Sliupas joined with others to publish an underground Lithuanian language nationalist newspaper, which was smuggled into Lithuania from outside. Together with Dr. J. Basanavicius and three other idealists, Sliupas published and edited the clandestine newspaper Ausra (Dawn) in Lithuania Minor from 1883 to 1884. Ausra, whose very name was suggested by Sliupas, is considered to be the driving force behind the Lithuanian nationalist awakening of the late nineteenth century.

Because of his ongoing nationalist activities, both Prussian and Russian police began pursuing him. Facing imminent arrest, Sliupas had to flee to the United States in 1884, where he would remain until 1918. He began studying at the University of Maryland in Baltimore in 1889 and graduated with a degree in medicine in 1891.

Dr. Sliupas was very active among Lithuanian-American immigrants, helping inspire in them a deep sense of national pride in their ancestral homeland. Although he was a free-thinker, he nevertheless helped establish several Lithuanian Roman Catholic parishes. He also invited Lithuanian priests to the Unites States and worked with them to promote a strong sense of Lithuanian ethnic and cultural identity among the parishioners. Being a powerful, inspiring, and uncompromising orator, Sliupas travelled extensively throughout the United States, delivering rousing speeches in which he urged Lithuanian Americans to unite in order to help Lithuania regain its independence.

Sliupas also edited newspapers and wrote or translated numerous books. Fluent in eight languages, he wrote thousands of articles both about Lithuania itself and about various medical topics for Lithuanian, American, Polish, German, Swedish, British, French and Russian newspapers. He also helped dozens of Lithuanian-American societies, several of which still are in existence today.

During World War I, Sliupas vigorously lobbied the United States government for diplomatic recognition an economic support for Lithuania. Having established a personal friendship with U.S. Senator Henry Cabot Lodge, head of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, Sliupas campaigned tirelessly in Washington D.C. for Lithuanian and Latvian independence. In 1918, Sliupas opened the first Lithuanian Legation in London. Then, in 1919, he was with the Lithuanian independence movement at the Paris Peace Conference. After returning to Lithuania, in 1919, he was appointed the first envoy to Latvia and Estonia.

Between 1921 and 1924, Dr. Sliupas taught hygiene and medical history at Birzai and Siauliai high schools. From 1925 to 1929, he lectured at the University of Lithuania in Kaunas. He also worked diligently to encourage investment in Lithuania's economy by investing much of his own savings in the country's economic development. Sliupas was the first mayor of the sea-side resort of Palanga, and he continued intermittently in this position from 1933 until Soviet occupation began in 1940. During June of 1941, he again resumed the role of mayor but was forced by the Germans to resign, because of his attempts to protect Jewish residents of the city.

Dr. Jonas Sliupas died in exile in Berlin, Germany on the 6th of November 1944.

Surviving family members transported his ashes to the United States, where they are buried in the Lithuanian National Cemetery near Chicago, Illinois.

Dr. Jonas Sliupas has been recognized numerous times for his life-long dedication to Lithuania's nationalist awakening and its restoration of independence. Among many other honours, Sliupas received three Honorary Doctorates from the University of Vytautas the Great in Kaunas. These include a doctorate in Medicine (1923), one in Humanities (1925), and one in Law (1939). Many organizations, both in Lithuania and in the United States, have declared him an honorary member. The Lithuanian government bestowed upon Sliupas the Gediminas First and Second Order medals. The Latvian government honoured him with the Three Star Second and Third Order medals, and the Lithuanian Post Office issued two stamps in his honour.

Jonas Sliupas will be celebrated as one of Lithuania’s true heroes and finest gentlemen ever, with an amazing record of achievements for his beloved homeland.

|

LITUANUS LITHUANIAN QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES Volume 37, No.1 - Spring 1991 ISSN 0024-5089 |

|

DR. JONAS ŠLIŪPAS (1861-1944)

Sister VIRGINIA MARIE VYTELL, CJC

Because it is true that "there is some bad in the best of us, and some good in the worst of us," the biography of Dr. Jonas Šliūpas written by the Lithuanian historian, Dr. Juozas Jakštas, shows both sides of a controversial figure.

Many people who have never met Dr. Jonas Šliūpas, or knew him superficially, regarded him "an anti-clerical atheist". The truth was not fully known, nor were answers provided to many questions. That Dr. Jonas Šliūpas loved his fellowmen and did everything possible within his power to show that love is seen throughout the pages of the book in Lithuanian.

The following excerpts in English based on the information found in the biography, is an attempt to reveal the side unknown to most Lithuanians in the United States, especially to those living in Northeastern Pennsylvania.

While yet a child in Lithuania Jonas was saddened because there were no more Lithuanian books for him to read. He told his mother that when he grew up he would write, and write, and write some more, until there were plenty of Lithuanian books for everyone. The parents of Jonas, hoping he would become a priest, sent him to his uncle's rectory to continue his education. This was the first far-reaching mistake.

A sensitive boy of a sanguine temperament, forced to live a severly disciplined life with a polonized uncle, Rev. A. Šliūpavičius, he had to study and pray in Polish, and to earn his education as a servant in the rectory. Many times he was tempted to run away from the unbearable situation. As a result it was here that the roots of an anti-clerical ideology were planted. Respect for the priesthood was destroyed. At the age of eleven he became a young skeptic displaying a rebellious spirit toward the clergy.* In 1873 when Jonas was 12 years of age, he was sent to study at a German School in Mitau (Jelgava) in central Latvia. His mother encouraged him to become a man of learning. "Son," she said, "we are poor villagers, uneducated people, that is why we are pushed around by others. As your parents we want you to attend school that you in turn would defend the under-privileged."

At Mitau Jonas remembered his mother's words. He observed the Latvians in their song festivals, attending Latvian theaters, and preparing cultural conventions. The Polish students had their own organizations and Polish books. With the support of wealthy barons had outings and entertainments.

Lithuanians, on the other hand, were not outstanding among the other groups.

No one paid any attention to them, neither the Church nor the School. The oppressive burden of non-recognition weighed heavily upon them and was a source of discouragement for the Lithuanian students. They had no Lithuanian activities. The majority were not wealthy. No one was there to inspire them with a self-assertive spirit or to raise their self-esteem as members of a nation with a long and glorious past.

Jonas was disturbed over the negative reality of the situation. It was then that he formed closer ties with leaders among the Latvians. He saw that Lithuanians and Latvians had more in common through similarities in their language and ethnicity than Lithuanians had with Polish.

In 1880 J. Šliūpas enrolled at Moscow University when Socialism, coming from Western Europe, strongly influenced the idealistic students. He identified with the radical stream. Often meeting with the Lithuanian students he was one of the founders of a student organization as the first of its kind, having its own newspaper, appropriately called Aušra, The Dawn.

In 1882 J. Šliūpas transferred to the University of St. Petersburg where his troubles started. He was arrested and imprisoned for three months for participation in a student riot. The following year, in keeping with his desire to be a writer, he evolved as one of the originators and editors of the Lithuanian newspaper in East Prussia, offering it the name Aušra.

The efforts of young Šliūpas to revive the Lithuanian language and culture were criticized in the Polish press. Šliūpas tried to reason with the Polish editor that love for one's own cultural heritage was not an expression of hatred for Polish. Both could exist as separate and equal entities.

As an outgrowth of the Lithuanian Renaissance Movement, Aušra's purpose was to present the nation's past as part of the whole and a model for the future. It presented Lithuania as a separate and independent political and cultural unit equal to other nations.

As editor of Aušra the young zealot deviated toward the liberal and sodalist trend. As a result of this tendency on his part he was dismissed from his position. Undaunted by the act of dismissal he hoped to be of service to Lithuanians in the New World. Through enlightenment and education he would discover the causes of his nation's mistakes and the source of the people's economic poverty and political decline.

At the age of 23, J. Šliūpas left Hamburg on May 28, 1884. He arrived in New York June 16th where he began the second chapter of his life. It was a chapter filled with hard work and incessant poverty, opposition and misunderstanding. As he later admitted in the golden years of his life he made many blunders in the role he assumed in his youth to awaken the Lithuanian people from sleep, to urge them on the path of national resurrection.

He saw as one of the greatest barriers met by Lithuanians in their efforts to revive their ethnic identity was the polonization of the masses through the Polish Church. Arriving in Brooklyn, New York, J. Šliūpas first involved himself with Lithuanians encouraging them to build a church of their own separated from the Poles. He described his hopes in a letter to his fiancee, L. Malinauskaitė:

"You will see, dearest Liudyte, that by the end of this year we will have a Lithuanian priest and a church of our own. The people will sing, 'Pulkim ant kelių' ('Let us fall on our knees') in New York and in Lithuania."

But it would not be as simple a task as he first surmised. As in other Lithuanian colonies in America, early Lithuanians in New York were associating with the Poles, were drawn into their Societies and joined their parishes as many did in Lithuania. A newspaper of their own, like Aušra, was needed to promote the cause of rebirth in a land of freedom.

The young Šliūpas, by offering the sum of $95, persuaded M. Tvarauskas, a polonized boyar who had a printing press in Brooklyn, to accept him as a partner for the publication of a Lithuanian newspaper. He felt this was his destiny in the New World to spread enlightenment and national awareness among Lithuanians.

To attract more subscribers to the newspaper which they called "Unija" (Union) the decision was made-to publish in both Lithuanian and Polish. In its editorial J. Šliūpas diplomatically blamed the nobility of old for Poland's downfall and the exploitation of the masses. However, among other things, he advocated national freedom and separation for smaller nations including Lithuania. This did not please the Poles or polonized Lithuanians.

The idea of separation and autonomy, — especially for Lithuania, — irritated them. They regarded Šliūpas as unfriendly to Poland and, as such, he was suspected of being a Russian spy. When they refused to subscribe to "Unija", M. Tvarauskas decided to publish the paper for Lithuanians alone. The senior publisher's decision was a victory for Šliūpas who hoped to continue the work begun by "Aušra" for the rebirth of Lithuanian consciousness. He had personal satisfaction in the work to which he felt called.

In the next publication Šliūpas wrote that only "Aušra" among the Lithuanian newspapers was in the hands of Lithuania's defenders, but it alone was not sufficient. He mentioned that the main purpose of "Unija" was to unite Lithuanian Societies, strengthen ties with the Fatherland, and to present the necessary conditions for Lithuania to regain her true identity and freedom.

Living frugally in the printery and sleeping in the same bed the two men worked hard for many hours. However, both had their differences. Tvarauskas, being a polonized boyar, understood the polonized mentality and was patient with Lithuanians fraternalizing with the Poles. J. Šliūpas, on the other hand, was uncompromising in his efforts to separate Lithuanians from Polish domination. This eventually led to break in their common efforts in publication.

Although the American historian, Michaelson, and the Lithuanian Encyclopedia, claim that Šliūpas resigned or was dismissed for verbal attacks on the clergy, Professor Jakštas in his book states that "Šliūpas was dismissed for his resistance to Poles." Be as it may, Jonas Šliūpas found himself unemployed, but not for long.

To continue his work for enlightenment J. Šliūpas founded "Lietuvos Mylėtojų Draugija", Friends of Lithuania. The first members were New York's tailors who supplied him with a modest dwelling and a printing press. One of their projects was to be the publication of "The Lithuanian Voice," Lietuviškas Balsas.

Feeling secure as an independent publisher J. Šliūpas sent for his fiancee, L. Malinauskaitė. They were married in 1885. The first issue of "Lietuviškas Balsas," appearing in July, 1885, had 500 subscribers. His wife, Liudmila, as a writer and poet, contributed articles for publication. Their first child, Aldona, called herself a "Lithuanian Voice baby" because she was often placed in an open drawer in the printery when her mother went to work as a seamstress to help support the family.

With the publication of The Lithuanian Voice the Poles soon felt the influence of Jonas Šliūpas as leader in the movement for separation. During the 500 anniversary of Lithuania's Christian Baptism (1387-1887) commemorated in a German Church, a Capuchin monk delivered a homily praising the Lithuanian nation. At the evening banquet a Polish choir offered entertainment, and the speakers consisted of one Pole, one Jew, and three Lithuanians among whom was J. Šliūpas.

Speaking in Polish, J. Šliūpas explained the negative results inflicted upon the Lithuanians when the Polish rulers used Christianity as a pretext to join Lithuania to Poland, and to deprive the people of their language and some of their land. He touched upon the contemporary Poles and their organizations, accusing them of injustice to Lithuanians. He exempted the Polish Socialist Party which, he said, was kindly disposed toward Lithuania.

The talk which Šliūpas delivered was prepared not so much to commemorate the historic event as to point out Poland's harm to Lithuania.

Then a pro-Polish newspaper, "Lithuanian Unity" published in Plymouth, Pennsylvania, aroused the anti-clerical passions of Šliūpas. The heated disputes which circulated in both newspapers, the Lithuanian Voice and Lithuanian Unity spilled over into the homes, meeting halls, and saloons of Lithuanian colonies. Another newspaper, "Saulė" (The Sun) published in Shenandoah, spread pro-Polish propaganda to convince Lithuanian Catholics to remain united with the Polish to retain their Catholic faith.

Rev. Alexander Burba, a pro-Lithuanian pastor in Plymouth who heard of the Šliūpas family in Lithuania, tried to convince Jonas Šliūpas that Lithuanians had enough to contend with in their efforts to regain their ethnic identity without arguing about religious matters. The most important task before them was strengthening their Lithuanian unity, not destroying it.

When subscribers to the "Lietuviškas Balsas" (The Lithuanian Voice) dwindled down from 500 to 100, and the printing press was seized by his creditors, the 28 year old Šliūpas and his family moved to Shenandoah, Pennsylvania in 1888. Convinced by his wife to seek another profession, J. Šliūpas departed in the fall to study medicine in Baltimore at the University of Maryland.

As a student at the University Jonas proved to be a person of gigantic work capacity. He persevered in his studies to receive a doctor's diploma and at the same time he became involved with Lithuanians living in Baltimore.

Calling a large gathering he received cooperation to establish the Lithuanian Education Society on December 22, 1889. It was a continuing attempt on his part to urge Lithuanians to seek freedom and self identity through education and enlightenment.

Before he graduated in 1891, a new arrival from Lithuania, Rev. S.

Pautienas, attacked J. Šliūpas and his Education Society calling it a nest of atheists. The resultant hostility between both men stirred Lithuanians in Baltimore. Šliūpas' sincere desire to educate the Lithuanian people who were deprived so long by their exploiters was not understood or appreciated by many.

Not discouraged by opposition, Dr. J. Šliūpas established branches of the Society in other locations. The first one in February of 1891 was founded in Plymouth through the cooperation of Rev. Alexander Burba, J. Andžiulaitis and J. Paukštys. Others had centers in Shenandoah, Pittston, Mahanoy City, and Philadelphia.

The periodical "Apšvieta" (Enlightenment) as the Society's news-sheet, was published abroad. Its first edition appeared in 1892. Its purpose was to change the thinking and attitudes of the people, and to motivate them to seek freedom and self-expression. He presented education and enlightenment as implements in Lithuania's future mission to spread learning and culture throughout Eastern Europe and Russia.

The young doctor envisioned a bright tomorrow for Lithuania in which truth and justice would prevail in international relations. He believed the time will dawn when the accumulation of arms will no longer be necessary, where the use of force will be replaced with peace and truth. With the formation of an International Tribunal Lithuania would exist without the need for battleships or a large army. Her resources and energy will be spent for her advancement and benefit and for that of the civilized world.

With the leadership of Rev. Alexander Burba, Lithuanians in the United States finally succeeded in joining Catholic Societies in a central Alliance free of Polish intervention. It was open to all Lithuanians of good-will. In a display of trust and acceptance the position of editor to their news media, "Lithuanian Unity", was offered to the free-thinker J. Andziulaitis.

A column was assigned for Dr. J. Šliūpas with the condition that he refrain from disparaging remarks against the polonized clergy.

Catholic leaders joined the Education Society and invited the members to a convention of the Lithuanian Alliance at Plymouth, Pennsylvania, on November 23, 1891. That it was a well-meant and trusting gesture was apparent but it was also a mistake in expecting the impossible. As Rev. Alexander Burba had been told in the past, "Water and oil would sooner mix than Catholics and free-thinkers (who considered the clergy as polonizers) would find common grounds for unity."

With Rev. J. Žilius as next president of the Lithuanian Alliance a new attempt was made to include all Lithuanians in the organization with the condition that religious questions and arguments pertaining to faith be conscientiously avoided. Considering the strength of their private convictions it was a hopeless expectation that such a compromise would last.

On May 21, 1901, at the 16th convention held in Wilkes Barre, Pennsylvania, the members separated into two organizations, one identified as The Lithuanian Catholic Alliance, the other as The Lithuanian Alliance of America.

Dr. J. Šliūpas had shown an interest in Socialism during his student days at Moscow University, it surfaced in 1897 at the time of the Lattimer Massacre where unarmed coalminers were shot during a peaceful demonstration. In a fiery speech he urged Lithuanians to follow the example of other groups to form a Lithuanian Socialist Branch. He suggested their centers be located in Scranton, Philadelphia, Pittsburgh, and Waterbury.

The ardor of Dr. Šliūpas was dampened when Lithuanians were not invited to the Socialist Congress at the Hague in 1904. However, joined by a new arrival from Lithuania, J. Širvydas, he called a Socialist Convention in Newark, New Jersey, on May 21, 1905, to centralize Socialist activities.

First called the Lithuanian Sodalist Party of America, the name was changed to The Lithuanian Socialist Federation. A disagreement over finances and a lack of better information on what Socialism promoted, Dr. J. Šliūpas resigned and the group disbanded.

Disillusioned with the Socialists he entered a new field of activity, that of the Lithuanian Patriots, and continued in active service to the day of his death, arousing Lithuanian consciousness both in America and Lithuania.

From 1915, a mature man of 54, Dr. j. Šliūpas joined the new American Lithuanian Patriots as the leading speaker, promoter, and fund-raiser. While practicing his profession as doctor he moved from one Lithuanian colony to another in order to influence many Lithuanians to work for their Fatherland's political independence.

Dr. Jonas Šliūpas was convinced that the greatest cause of poverty and moral decadence was the people's ignorance. To raise their level of living, education was needed. He contributed his share in newspaper publications, in books, — both original and translated, — and by giving lectures and organizing study groups. He emulated the methods used by other educators to promote his efforts.

Formed in his youth with a liberal world-view, Dr. Šliūpas made no compromises in his life. He upheld the belief that learning and the harnessing of nature's powers would bring blessings to humanity. His writings revealed that he was the product of the 1789 French Revolution. He expressed himself as a global rationalist with humanity's future in mind. As the 19th century leaders of the great liberal movement he believed in a bright future for the world.

Having a fair knowledge of 8 languages including English, Dr. Šliūpas read extensively and translated much of his acquired knowledge into Lithuanian.

However, the majority of Lithuanians who came to Northeastern Pennsylvania have had little or no opportunity for an education in their Fatherland. It stands to reason that in spite of his exalted aims and sincere love for the Lithuanians, Dr. J. Šliūpas was unable to reach the majority of the people who, living a strenuous life as coalminers to feed and clothe their families, had little time left for education for themselves.

Because of the scandalous example of a few clerics, Dr. J. Šliūpas felt inclined to condemn the entire priesthood, — with a few exemptions, — calling them the blight of the nation, a vocation unfit to lead the people, and living for the good of one's own caste.

Those who tried to limit, through slander and criticism, the extent of the doctor's influence, suceeded in making him widely known. The effect was contrary to intent. Dr. J. Šliūpas evolved as a controversial figure, loved and revered as a hero by some, or condemned and rejected by others. It was difficult to be indifferent to him.

Those who knew his past as a student in Lithuania and understood his motives, were not swayed by the polonizers. To them, Šliūpas was a great Lithuanian patriot, a public activist of wide interests, the author of numerous patriotic and social writings which wielded powerful incentives among Lithuanians in the United States to work for Lithuania's ultimate freedom.

According to Dr. J. Jakštas in his book, Dr. Jonas Šliūpas, (page 10) "researchers of Lithuania's past would be considered partial and prejudiced if they did not attribute to Dr. J. Šliūpas a merited place in the history of Lithuania's national rebirth." On the whole, the liberal and anti-clerical propaganda included in the lectures and writings of Šliūpas did not penetrate the masses. Understanding of human nature, with all its imperfections found in any calling or profession, kept the people true to the teachings of their faith.

What really mattered was the gigantic work Dr. J. Šliūpas was able td accomplish on two continents in spite of poverty, the apathy and indifference on the part of some Lithuanians, and the numerous obstacles he had to overcome through hard work and sheer force of will. Because he believed he was called to be a forerunner of Lithuania's rebirth as a nation gave him strength and courage to persevere in his mission.

To the wearied Lithuanian people he planned an improved future. Through knowledge and freedom they would raise their families to value their ethnic treasures. He stressed that knowledge does not replace virtue; there is a greater need for compassion and love. If the principle prevailed, "Do nothing to others you do not want done to yourself," then learning and creativity would turn this world into paradise.

Throughout his life the doctor retained his strong convictions. He held firmly to the two concepts of education and morality as the guiding light to a successful future, that good results would follow the formation of a national and world culture. Education based on moral principles would establish world cooperation for a lasting and blessed peace.

Whatever Dr. Jonas Šliūpas was able to do in his turbulent life he accomplished to the best of his ability. He had been numbered among the poor most of his life yet he did not seek his own welfare but worked for the good of many. That he made mistakes he humbly acknowledged. "But then," he asked, "what forerunner or prophet succeed-ed in avoiding them?"

Concern for Lithuania's welfare was an important priority in the life of Dr.

J. Šliūpas. Those who understood his deep concern hailed him as a symbol of Lithuania's freedom, a renewer of Lithuanian consciousness in America and in Lithuania. He attracted millions who had the same desire for release from foreign domination. He was recognized as one of the founders of Aušra, as a pioneer of the Lithuanian press, a teacher, lecturer, a promoter of progress and freedom.

Sensitive, an individual of a sanguine temperament, he strongly defended his personal views of patriotism. Those who opposed his ideas he regarded as foes of Lithuanianism. It was not without reason that those who did not agree with him labelled him a fanatic, and intolerant of other people's opinions.

His materialistic viewpoints, his attacks on the church and the clergy, were similar to the tactics of the Bolsheviks, yet the doctor did not consider himself one of them. He condemned the Nazis and Fascists but he did not condemn the Communists until he saw them in action. In his writings, "Laisvoji mintis" (The Free Mind) and "Naujoji Gadynė", (The New Era) he promoted democracy, love for the Fatherland, and he highly approved the Lithuanian Ethnic Association. These ideals were definitely not promoted by the Communists.

Since his childhood days Dr. J. Šliūpas had desired to be a writer, to enlighten the people, to share his knowledge with others. He began his journalistic contributions to the press in 1882 and continued to write through 58 years until 1940. He had a wide variety of topics ranging from family life, to history, to politics and religion, to national needs and morals, to health questions, to literature and biographies, to Lithuania's past and hopes for the future.

When leaving Lithuania in 1883 Šliūpas had planned to return when independence was attained, so sure was he it would happen. For many years he sacrificed, worked, and struggled, and endured opposition and hostility. In his numerous writings and lectures he encouraged Lithuanians to prepare to be worthy leaders for their emerging nation.

As a practicing physician Dr. Jonas Šliūpas lived with his family on North Main Avenue in Scranton, Pennsylvania, before the outbreak of World War I.