THE VOICE OF INTERNATIONAL LITHUANIA

|

VilNews has its own Google archive! Type a word in the above search box to find any article.

You can also follow us on Facebook. We have two different pages. Click to open and join.

|

Archive for 2011

- Posted by - (0) Comment

OPENED TODAY, FRIDAY 16 DECEMBER 2011

First Jewish library in

Lithuania since WWII

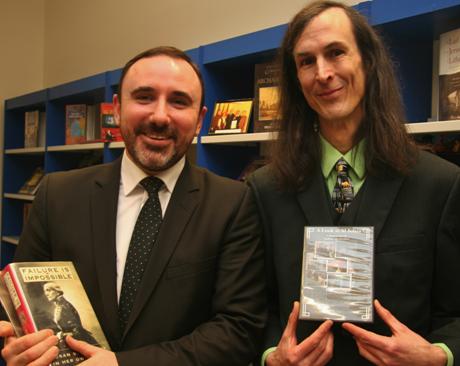

“Failure is impossible,” is the title of the book that was held by Lithuania’s Minister of Culture, Arūnas Gelūnas (left), at the opening of the Vilnius Jewish Public Library Friday 16 December. Wyman Brent, the Californian book collector behind the amazing collection of more than 5.000 books, plus videos and CDs, says today is one of the happiest days in his life.

Photos: Aage Myhre.

Friday 16 December 2011 the new Vilnius Jewish Public Library, located at Gedimino Avenue 24, 2nd floor, in Vilnius was officially opened. Guests from USA, Israel, European Parliament, Seimas (Lithuania’s parliament) of the Republic of Lithuania, Government of the Republic of Lithuania, Lithuanian Ministry of Culture, Lithuanian Ministry of Foreign Affairs and others were participating.

On Saturday 17 December 2011, from 11:00 to 17:00 the library will be open to the general public, giving everyone an opportunity to view the premises, the collection of books and photographs, the exhibits, and a presentation of a slide-show giving a retrospective of the establishment of the library. Visitors will be greeted and will have the opportunity to speak with the initiators of the library.

Panel at the press conference (l/r): Davia Kiminaite, Wyman Brent,

Miša Jakobas, Petras Zurlys, Arūnas Gelūnas and Petras Austrevičius.

Daiva Kiminaite is now Head of the Vilnius Jewish Public Library |

The composer Anatolijus Šenderovas with Wyman Brent. |

Žilvinas Beliauskas (left) and Petras Zurlys have both done a great job

for the realization of the library.

Read also:

The California Baptist who collected 5000 Jewish books and brought them all to Lithuania

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - (10) Comment

OPENED TODAY, FRIDAY 16 DECEMBER 2011

First Jewish library in Lithuania

since WWII

“Failure is impossible,” is the title of the book that was held by Lithuania’s Minister of Culture, Arūnas Gelūnas (left), at the opening of the Vilnius Jewish Public Library Friday 16 December. Wyman Brent, the Californian book collector behind the amazing collection of more than 5.000 books, plus videos and CDs, says today is one of the happiest days in his life.

Photo: Aage Myhre.

Friday 16 December 2011 the new Vilnius Jewish Public Library, located at Gedimino Avenue 24, 2nd floor, in Vilnius was officially opened. Guests from USA, Israel, European Parliament, Seimas (Lithuania’s parliament) of the Republic of Lithuania, Government of the Republic of Lithuania, Lithuanian Ministry of Culture, Lithuanian Ministry of Foreign Affairs and others were participating.

On Saturday 17 December 2011, from 11:00 to 17:00 the library will be open to the general public, giving everyone an opportunity to view the premises, the collection of books and photographs, the exhibits, and a presentation of a slide-show giving a retrospective of the establishment of the library. Visitors will be greeted and will have the opportunity to speak with the initiators of the library.

The impetus for the library was from a private collector, humanitarian, and visitor from the USA -- Mr. Wyman Brent. His initiative was to bring to Vilnius, and thereby to pass to Lithuania, a collection containing more than 5,000 valuable books. The collection consists of books by Jewish authors, as well as books on Judaism by non-Jewish authors.

Wyman Brent first came to Vilnius in 1994, telling that he fell in love with Vilnius already by then. Over the course of several years, he become interested in Jewish culture, history, and heritage, and came to follow the path towards his dream -- to establish a Jewish Library in Vilnius.

Wyman Brent is convinced that as soon as the library officially opens its doors, then the love of Litvaks (i.e., Lithuanian Jews) and their longing for their old motherland of Lithuania will encourage a continuous flow of literary, artistic, and informational valuables to The Northern Jerusalem, as Vilnius was once called. Moreover, the library will urge many peoples to visit Lithuania in attempts to rebuild devastated human and cultural treasures, and to re-establish internal and international bridges.

Activities of the Vilnius Jewish Public Library will encourage visitors to revive the traditions of Jewish book culture and community libraries, offering a public space to encourage knowledge of the capital’s cultural diversity and history, and will become a cultural center with a variety of continuing exhibitions, events, meetings, and concerts.

Vilnius Jewish Public Library is founded as a structural sub-division of the Vilnius County Adomas Mickevicius Public Library.

Panel at the press conference (l/r): Head of the library Davia Kiminaite, book collector Wyman Brent,

Rector of the Vilnius Jewish School Miša Jakobas, Director of the Lithuanian Librarians’ Association Petras Zurlys,

Minister of Cultre Arūnas Gelūnas and Member of Parliament Petras Austrevičius.

Daiva Kiminaite is now Head of the Vilnius Jewish Public Library.

If questions or requests, please write Daiva at

daiva.kiminaite@amb.lt

Žilvinas Beliauskas and Director of the Lithuanian Librarians’ Association, Petras Zurlys, have both done a great job

for the realization of the library.

This couple has played a major role in supporting and contributing to the library from their Helsinki location,

Inna Rogatchi and Michael Rogatchi of the ‘Inna & Michael Rogatchi Foundation’.

Rector of the Vilnius Jewish School Miša Jakobas with Wyman Brent.

Composer Anatolijus Šenderovas with Wyman Brent.

Lithuania’s Minister of Culture, Arūnas Gelūnas interviewed by Lithuanian Radio’s correspondent Olga Ugriumova.

Tenor Mindaugas Zimkus with Wyman Brent.

Also Lithuania’s Prime Minister, Andrius Kubilius (centre), came to participate in the opening ceremony.

Photo: William Adan Pahl (Billy Pahl)

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - (0) Comment

Memory of the Vilnius

sound that once was

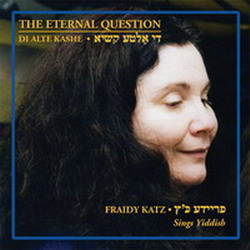

"The Eternal Question” / “DI ALTE KASHE”

FRAIDY KATZ sings Yiddish

Produced by Wolf Krakowski and Jim Armenti

The Eternal Question

Top Ten Records of the Year

One World Radio

WHUS, UConnecticut@Storrs

Rated 4.5 stars, George Robinson, Jewish Week, Read Review

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - (0) Comment

‘Day and Night’ is an epoch-making play for modern Lithuania

O P I N I O N / R E V I E W by Birutė Ušinskaitė

Cover of playbill

It was just another rainy, temperate evening in early December of the year 2011, but the play I was privileged to see at the Kaunas Chamber Theater, Day and Night, proved to me, a proud woman of Vilnius, that not all that is bold and brilliant here comes from our capital.

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - (1) Comment

‘Day and Night’ is an epoch-making play for modern Lithuania

7 December 2011

O P I N I O N / R E V I E W

by Birutė Ušinskaitė

Cover of playbill

It was just another rainy, temperate evening in early December of the year 2011, but the play I was privileged to see at the Kaunas Chamber Theater, Day and Night,proved to me, a proud woman of Vilnius, that not all that is bold and brilliant here comes from our capital.

For the first time in our modern Lithuanian history, in my experience at any rate, a Lithuanian play on the Holocaust did not try to deflect attention ― or responsibility ― to the Germans or to some “complicated times” or to some pseudo-objective forces milling about on all sides. Or, to stick to some “kosher” theme like the dilemmas of Jacob Gens and the Judenrat in the Vilna Ghetto in the cause of talking about everythingexcept what is frankly the main point for our country: the voluntary participation of thousands of our countrymen in the mass murder of the Jewish citizens of our own country, in some cases starting before the Nazis even arrived.

For the first time in my life, I have been able to enjoy a quality literary creation where the barbaric and pathologically racist and fascist nature of some members of the Lithuanian Activist Front (LAF) is shown exactly for what it was. In Lithuanian. By and for a Lithuanian audience. That makes me proud.

It is a small theater, and there were perhaps only a hundred people present, but it was in its own way a grand national catharsis that makes me as a born and bred Lithuanian citizen very patriotic in the European sense of the word, where patriotism is loyalty to finding out and facing the truth and not some kind of nationalist whitewash or prejudice toward minorities or other Others.

From the playbill: Period photos and a 1941 poster tell the audience that this will be no whitewash

Day and Night is a signal that at long last we are becoming a mature nation where a theater production can finally portray the simple truth that a not inconsequential portion of these LAF “heroes” were murderers of civilians and spreaders of hate toward fellow natives of their country. That it was done artistically, not with some pietistic declaration, but with a strong and unforgettable scene of two LAFers wrapping the white band around their new colleague’s arm, made it incalculably stronger.

The duration of the two-part play is two and a half hours. I personally found that on the long side, and it could benefit by consolidation of some of the latter scenes. One other point is the choice of the music by composer Faustas Latėnas. In my opinion, “general” Yiddish popular songs are not the best choice. I think that Yiddish folk songs of Kaunas, and specific songs of the city’s Holocaust-era ghetto would have made those portions more authentic. Strange to be making such a fuss about these two things, but maybe that is because just about everything else seemed to be almost perfect from the subtle make-up of the actors, the costumes and hauntingly minimalist set, to the singularly effective lighting effects. The Hitchcock-timed dimming sequence at the beginning of the scenes conveyed a slowly unfolding horror. Yes, and the magnificent acting.

Even though the characters of the play have no necessarily real prototypes, the plot is based on historical facts, testimonies of witnesses and archival documents from the Holocaust era. The actors even read some of the documents aloud and quote them in their dialogues, like, for example, a sickening antisemitic article from a newspaper.

Naturally, some viewers in our country might not understand the significance of the play and why it is necessary to speak about the Holocaust in Lithuania today, so the question naturally arises: Why was this play written in the first place?

As playwright Daiva Čepauskaitė puts it:

“I was searching for a serious and principled topic. And the Kaunas Chamber Theater suggested that I should write about the Holocaust in Lithuania. I took this as a challenge, both as a playwright and as a human being. It was a really difficult task for me as a professional ― it was difficult to find the right language, form and the way to tell the story. But the topic enriched me as a person; I had an opportunity to come up with certain principles and a personal approach. Therefore, I have an answer to the question why I have written this play: I wrote it because I am Lithuanian, because it is our common history and because I do care about things that happened, are happening or will happen in Lithuania. And because it hurts.”

It is a tragic love story, the impossible love of teenagers ― a Lithuanian boy Andrius and a Jewish girl Milda, who are entrapped in a bizarre scenario. The main characters are played by young and inspirationally talented Lithuanian actors: Simona Bladženauskaitė and Vytautas Gasiliūnas. They invent a strange game. They are playing the Holocaust in Lithuania and acting out the love story of Milda’s grandmother Golda, who is now old and not clear of mind. Golda had in fact gone mad when her long-time-ago lover Kostas accidentally got shot right before the end of the Second World War, when Golda turned nineteen.

Andrius and Milda are unable to live their own lives. They are predetermined incarnations of ghosts of their city’s past.

Sometimes Andrius resists Milda’s wish to live in the past. And that is when she starts numbly counting aloud to herself. And he invariably succumbs.

It seems to me that many people in Lithuania, whether they want to know it or not, cannot calmly live out their years and roam the streets of the old ghetto in Vilnius, Kaunas or Šiauliai without getting possessed by the dybbuk of our past. In order to let the old wounds heal and to prevent such horrors from happening once again, it is important to tell the young generation of Lithuanians what we have done to our neighbors. Therefore, it is significant to speak the simple truth about the Holocaust in Lithuania, as well as about the lamentable antisemitism today. On the way back from Kaunas, I opened the 3-4 December 2011 weekend edition of our best daily, Lietuvos rytas, only to find a three page antisemitic yarn, advertised with the blurb “Mystery of the Millions” on the front page over a picture of a Jew in the Kaunas synagogue. For shame.

Daiva Čepauskaitė continues to explain what drove her to write the play.

“When I was writing the play, I was reading some documents in the archives, and one protocol of the court caught my eye. The defendant was asked why he was murdering Jews and he replied: “Because I am Lithuanian.” Then I thought about the many meanings of this word. After all, those who rescued Jews were also Lithuanians. The same word can mean the most honest fight for the freedom of the people, simple humanity, or the lowest instincts. I am also Lithuanian and I wrote this play […] because life and death have no nationality, and because inhumanity is our common enemy.”

The two timelines of the play are looped. Today’s reality intertwines and intersects with the past, and the points of intersection are precisely the most important ones. The ones that hurt like wounds that have never healed. The wounds and the pain are real. Kostas burns his arm badly in order to be able to see Golda, the Jewish girl, with whom he falls passionately in love. He comes on Friday night and Golda has to violate the Sabbath law in order to help him, because Jews are not allowed do any work on the Sabbath.

Golda’s father Berelis Taicas (Berl Teitz), a pharmacist, explains to Kostas what it means to be a Jew: Jewish happiness is a very short time between long periods of unhappiness and misery, which change like day and night. Berelis Taicas says that God has punished him, because he has no son, only two unmarried sisters and three unmarried daughters, and, even worse, he thinks that one of the daughters is too smart for a girl, so how could he be happy.

Then the war breaks out and everything changes, at least for the Jewish citizens of Lithuania. The Red Army withdraws from Kaunas and massacres of Jews start immediately. On 25 June 1941 the German advancing troops (Vorauskommando) enter Kaunas. The situation is horrendous. The infamous massacre of Jewish civilians takes place at the Lietūkis garage in Kaunas on 27 June. It seems that the earth under one’s feet is catching fire. The gang of Klimaitis rages and murders people. Some Kaunas Jews are burned alive. One can smell the fear in the air and some of the city’s Jews try to escape or go into hiding.

On 12 July 1941, a regulation is issued for Jews to wear a yellow star, 8-10 cm width in diameter on the front and on the back. They are not allowed to leave home after 8 PM. Another regulation sets out that Jews have to leave their homes and move into a ghetto in Vilijampolė (Slabódke in Yiddish culture) by 15 August. In Kaunas, Jews are taken to the 7th Fort. Almost all of them are gunned down by volunteer Lithuanian “partisans”. The murderers are nowadays sometimes hailed as “anti-Soviet patriots”.

Moreover, the Provisional Government of Lithuania does not say a word to condemn the ongoing genocide. After five weeks the mass graves of the victims near the 7th Fort start to cause problems. The local inhabitants start to complain about the bad smell. In the second half of July it is forbidden to swim in the Nemunas and the Neris rivers because it is believed that the water is contaminated with the “poison of the corpses”.

Kostas joins the Lithuanian Activist Front (LAF) together with his friends, who instigate racial hatred and genocidal antisemitism. Kostas becomes a Jew-killer, but he saves Golda. Golda’s father is taken away by the young fellows who are wearing white armbands and he never comes back. Golda finds shelter in a hiding-place, a pit under the floor of his house. By day Kostas and his friends murder other Jews, because their task is to liquidate all the “Communists and Jews” though it is Jews who are the primary objects of their passion for murder. By night he makes love to Golda.

Scene from Night and Day. Courtesy Vaida Gedzevičiūtė / Kauno kamerinis teatras

Once Golda inquires of him whether he had shot many of their neighbors and Kostas replies that he had murdered all of them. So that nobody would interfere with their love. Golda attempts suicide, but later she finds out that she is pregnant. One night, after giving birth, she is allowed to have a little walk in the garden. She looks at the starry sky and screams: “Oh, God, the sky is full of Jews! They all are there!”

There are good times and there are bad times in every nation’s life, just like there is day and night, and sometimes we make things of which we cannot be proud, but the story of the Holocaust in Lithuania is the darkest page in the country’s history.

However, the creators of this play, perhaps for the first time in Lithuania’s history, managed to examine and analyze this topic with full honesty. They are not trying to solve any historical dilemmas; their only goal is to frankly and bravely tell what really happened and what kind of mindset made this calamity possible.

The scenes from today actually do more than serve the literary purpose of incarnations of old souls emerging among us, among people just like us, a forever attractive literary device. They are a blunt warning about the advent of antisemitism right here and now which is also presented on stage as it is on the streets (and in our “best” newspapers).

This epoch-making play can and should be translated into English and other languages and produced abroad.

It will do Lithuania proud.

Diena ir naktis.

KAUNO KAMERINIS TEATRAS.

Directed by Stanislovas Rubinovas. Art: Sergėjus Bocullo. Music: Faustas Latėnas.

Starring Simona Bladženauskaitė and Vytautas Gasiliūnas; Alma Masiulionytė, Aleksandras Rubinovas, Violeta Steponkutė; with Kristina Kazakevičiūtė, Daiva Škelevaitė, Asta Steponavičiūtė, Edita Niciūtė.

Birutė Ušinskaitė is a Vilnius translator and memoirist.

Three Page Antisemitic Mini-Tract runs in Lithuania’s Mainstream Daily

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - (0) Comment

Olga Zabludoff: Reply to Donatas Januta re Holocaust in Lithuania

It is most powerful when Lithuanians themselves stand up and speak out

Olga Zabludoff

Dear Donatas,

The ball is now in my court and I am happy to continue the discussion. It might be that you and I have an irreconcilable difference of opinion on the subject of Jewish contributions to the Lithuanian economy, or -- as you maintain -- the lack of Jewish contributions. Let me try once more to convince you.

You point out that on the eve of World War 1 the economy of “Mother Russia,” which had an insignificant Jewish population, and the economy of Lithuania, which had a substantial Jewish population, were pretty much equal – depressed and backward. You emphasize that in spite of the fact that Jews participated in Lithuania’s economy but did not participate in the economy of czarist Russia, there was no virtual difference in the two economies.

Logic 101: If Jews had not been present in Lithuania at the time and therefore had not participated in its economy, perhaps Lithuania’s economy might have been even weaker than that of “Mother Russia.” Participating in a nation’s economy does not mean controlling the economy of that nation, let alone an entire region. Conditions in Eastern Europe during that period were what they were; the result was a weak and undeveloped economy.

Read more...

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - (9) Comment

Olga Zabludoff: Reply to Donatas Januta re Holocaust in Lithuania

It is most powerful when Lithuanians themselves stand up and speak out

Olga Zabludoff

Dear Donatas,

Please excuse my long delay in responding to you. I have been traveling but have kept up with my reading of VilNews. There is much catching up to do. And since “Tautietis” joined our discussion with his comments posted on 20th November, I am going to address his points here also.

I must say that it is exceptionally trying to find logic in Tautietis’s arguments as he leapfrogs from 19th century Tsarist Russia into the “so called ‘Golden age’ for Lithuanian Jews,” as though the two historical periods were simultaneous. Only during Independent Lithuania (the period between the two world wars) did the Jews of Lithuania experience anything resembling a golden age, and that was very short-lived. (More on this later.)

Tautietis writes: “It is no secret that Jews accepted [the] Russian language and culture more readily than Lithuanians – and were better positioned to take advantage of the opportunities that were there in Imperial Russia.”

I quote from Lithuanian Jewish Communities by Schoenburg & Schoenburg, 1991: “Russia, a country that had always excluded Jews, suddenly found itself sovereign over the largest concentration of Jews in the world. In addition to the innate hostility toward Jews held by most Russians, especially the nobility, the problem was compounded by the fact that Jews and the Jewish communal structure did not fit the feudal structure of Russian society” (page 28).

In the Russian Empire Jews were forced to live in the Pale of Settlement and were excluded from many occupations. They had few choices of how to earn their living. “The poorest portion of the Pale of Settlement was Lithuania. As economic conditions deteriorated, Litvaks moved to better areas . . . Some settled in Latvia. Others went to the Ukraine, northeast Poland, or to other parts of the Pale. . . (pages 31-32).

“With the assassination of Tsar Alexander II in March 1881, all pretense of liberalism ended and the repression of the Jews intensified . . . Between 1880 and 1914, over two million Jews had emigrated to the West . . . The emigration was heaviest from Lithuania” (page 32).

Your statement referring to supply and demand is sheer nonsense: “If you own the market, you are in position to set the demand.” No one can set the demand, and the Jews were mainly small-scale entrepreneurs, not monopolists who “owned the market.” No need to waste any more words on that subject.

Donatas, in your 22nd November post, you write: “. . . But if the Lithuanians themselves had been allowed to have a broader hand in the economy, it [the economy] might have been a lot better, too.”

When were the Lithuanian people not allowed to have a hand in their country’s economy or barred from any particular occupations? Even before Independent Lithuania the Lithuanian people were free to select their occupations. It was their choice, not their mandate, to earn their livelihood mainly through farming. It was a tradition, not a law imposed against them. There seems to be a trend, among those who take your side of the debate, to switch roles, to create the impression that the Jews were the controllers and the Lithuanians, the underdogs. Please, let’s not mangle history to that extreme. It is too reminiscent of the anti-Semitic propaganda during the 1920s and 1930s that lit up the stage for the horrors that were to follow.

I am frankly stunned by your statement that Lithuania’s vote against Palestinian membership in UNESCO “was an example of Lithuania’s cowardice in succumbing to pressure from Israel and Israel’s ally the United States.” In one ultra-nationalist sentence you managed to damn both your ancestral land and the land you live in. To say nothing of your apparent negative attitude toward Israel.

I remember well the incident you refer to when the Los Angeles Lithuanian Community refused to permit a troupe of Yiddish dancers to perform at a folk dance festival. I guess they didn’t want the Yiddish presence because it might have been symbolic of a time when Lithuania had a Jewish population . . . and all that that memory entails. I agree with Efraim Zuroff that this was an anti-Semitic expression, but I don’t think it would happen today.

As far as the statement you attribute to Zuroff that “the Lithuanian émigré community consisted largely of descendants of war criminals,” I think Dr. Zuroff knows better than to hold the children responsible for the sins of their fathers. What he may have meant was that since many of the Lithuanian war criminals did flee after the war to the US and Canada, fearing reprisals from the Soviets, their children could have been indoctrinated with anti-Semitism. Children learn from parents and often adopt the same values. That’s why education of the young is so important.

I do not know Irena Veisaite or Yves Plasseraud (other than through their brief writings I have read recently in VilNews), so I cannot judge their politics or their characters. But let me say that I seem to understand and feel more connected to people like Dr. Saulius Suziedelis and Didier Bertin. I believe they are every inch as sincerely interested in reconciliation between Jews and Lithuanians as Veisaite and Plasseraud. They lay the issues on the table; they believe the problems of the past and present must be confronted (or embraced) and thereby overcome, and then it will be possible to start with a clean slate. I believe in that kind of common-sense, organized and open approach. It defines Democracy.

Yes, I reiterate: the majority of the Soviet partisans in Lithuania during World War II were not Jewish. There were approximately 5,000 Soviet partisans in Lithuania operating in the forests around Vilnius. Your numbers of Jewish partisans total about 300, and the units they were in were the Jewish partisan groups which of course had the largest numbers of Jews.

I will stand by my statement that there was inconceivable savagery when hate and greed overwhelmed love and loyalty in Lithuania in 1941. And I do mean to imply that most of the Lithuanians were guilty to various degrees. I still maintain that 99.5 % of the local population did not participate in the murder of Jews. But the 0.5 % who did actively participate totaled at least 15,000 people. The ratio was 1:13 – one killer for every 13 Jews. The rest of the “good” people turned a blind eye. There were a small number of saints – those Lithuanians who risked their lives and their families to do what they considered the right thing, the Christian thing. To say that they were heroes does not do sufficient justice to the magnitude of their deeds.

During my trips to Lithuania I have befriended as many non-Jews as Jews. My dear friend Domicele, who died a few years ago at age 91, told me the story of the Holocaust in her small town. Many men and women, even with children in tow, went as spectators to the killing site to watch the executions. Once all the Jews were in the pits, the looting began. The killers were given first choice of the spoils. Very few did not participate in the frenzy of stealing whatever they could from Jewish homes. They felt “entitled.” Even the priest came with a wagon and loaded up furniture and other Jewish possessions. All this was going on while the earth at the mass graves was still moving. At night thieves came to the graves to extract gold teeth from corpses.

If this isn’t savagery, what else can you call it? It happened in towns and villages throughout the country. I heard the same stories from Jewish survivors and non-Jewish witnesses. It is documented heavily in books, memoirs and oral testimonies.

Your closing paragraph of your 22nd November article reads: “. . . What I would also like to see is to have the Soviet inflicted tragedies, including the “Kaniukai” slaughter, be recognized and acknowledged in the West for what they were, just as the German inflicted tragedies have been, and to have their perpetrators judged as the criminals they were and are. And I don’t see how this is disrespectful of the Jewish dead or the Jewish survivors, or how it has anything to do with the Holocaust.”

In theory your request does not sound unreasonable, but look at it this way: First of all, surely you accept by now that the “German” inflicted tragedies were inflicted mostly by the Lithuanian collaborators. In Lithuania the Germans did not have or need much manpower because they had all the help they needed from the locals. Secondly, Lithuania has not brought to justice a single Lithuanian war criminal, not even the ones deported from the US. Yet you would like to see the former Jewish partisans “judged” as war criminals?

Your article of 24th November is a detailed account of the relationship between Lithuanians and Jews during the period of Independent Lithuania which began at the close of World War I. Your closing paragraph: “The Jews of Lithuania in 1918-1920 contributed financially and politically to the re-establishment of Lithuania as an independent sovereign state. And they also fought and they died as warriors with weapons in their hands, next to their Lithuanian comrades. . . .”

Let me take the theme of Independent Lithuania to its conclusion by quoting from Lithuanian Jewish Communities:

“The Jews supported Lithuanian aspirations for independence. In 1919, the Lithuanian delegation to the Versailles Peace Conference sent a letter guaranteeing the Jews of Lithuania the ‘right of national-cultural autonomy.’ This was followed by laws allowing Jewish autonomy and a constitutional provision protecting the rights of large minorities. Jewish communal institutions were established and national conferences were held. The period 1919-1922 was the Golden Age for modern Jewish autonomy. Thereafter it decayed due to pressure from reactionary clerical groups and because the Jews were no longer needed to further Lithuanian nationalism.

“In the economic sphere, Lithuanian cooperatives were formed under governmental auspices which had the effect of cutting the Jews out of their traditional middleman merchandising positions. Many Jews earned their livelihood in crafts, some in the professions and a number in the import-export trade. As time passed, the numbers in each declined with the places taken by Lithuanians. The slogan was ‘Lithuania for the Lithuanians.’ . . . The Jews lived in poverty. Many Jews emigrated” (pages 38-39).

“Elections in May 1926 gave a majority to the left wing which was followed in December by an army coup d’état which instituted an extreme nationalist government and totalitarian rule. The constitution was soon abolished and with it many democratic provisions and rights.

“The program of the nationalists was based upon xenophobic nationalism and the church. Education was controlled to further these ideals. One of the objects of derision were the Jews who were considered foreigners. Lithuanian newspapers in the 1930s were so anti-Semitic, they easily rivaled Nazi publications in vitriolicity” (page 37).

“Most Jewish leaders welcomed the creation of a Lithuanian state in which Jews were promised relative autonomy. . . . it seemed that the Jews would have an opportunity to develop their national life. However, these minority rights were abrogated starting in 1924. The Lithuanian government encouraged the development of an ethnically Lithuanian urban middle class to compete with, and ultimately to displace, Jewish businesses” (The Litvak Legacy, Mark N. Ozer, 2009, page 81).

Excerpt from a letter dated 1 October 1924 from my uncle Dovid Shlomo to his brother who had managed to get to Havana a year earlier [translated from Yiddish]:

“Times are very critical here. There are many bankruptcies in Kovna, and this is spreading to us. They chased out the national council. They are requesting that Jewish signs be removed from businesses. We feel like we’re being driven out – like we’re being exiled.

“Dear Brother, maybe you have a way to get us out of here. It would be very good because things are getting worse, not better. . . .”

From a letter dated 15 February 1939 from Dovid Shlomo to his brother now in the US [translated from Yiddish]:

“The news from us is not cheerful. Firstly, they are not giving Jews any permits for restaurants. Just imagine: what will I be able to do? My mind is already drying up. Secondly, there is even a worse problem here: they are telling us to tear down the house. This is already underwritten by the powers-that-be. I can still appeal to the interior minister, but who knows what his thinking is. In the best case, if they would allow us to keep the house, then they would demand a renovation which would cost as much as 4,000 litas. So you can see how I can allow this.

“Now there are Christians who want to buy the house. They won’t be subject to any hardship. So I don’t know what to do. If you would bring us over, then I would sell the house. . . .”

First they were pushed out of their business, then out of their house, then marched to the ghetto and from there to the mass grave. That was the fate of my uncle Dovid Shlomo, his wife Tsila, their two little daughters and my grandmother who lived with them.

In regard to your post of 2nd December, I find your denunciation of Dr. Dovid Katz (a scholar you formerly admired) truly offensive and a strong case of public character assassination. It is the same tactic employed by the Soviet regime which you so abhor. If one expresses an opinion contrary to the party line of the government, the message must be crushed and the messenger discredited and denounced.

You speculate that Professor Katz was removed from his position at Vilnius University after 11 years because he doesn’t speak Lithuanian. It makes no sense that after a successful tenure of 11 years, Dr. Katz would suddenly be discontinued for not speaking Lithuanian. This is a ridiculous trumped-up charge. It is more likely that Katz’s efforts to tell the truth is the unspoken but real reason for his dismissal. Long live Democracy in Lithuania!

Meanwhile there are encouraging signs from bold young Lithuanian voices. See

http://defendinghistory.com/%E2%80%98day-and-night%E2%80%99-is-an-epoch-making-play-for-modern-lithuania-by-birute-usinskaite/26186#more-26186

Both the reviewer, Birute Usinskaite, of a stage play which opened recently in Kaunas and the playwright of Day and Night, Daiva Cepauskaite, are to be applauded for their brave, clear messages.

See also:

http://defendinghistory.com/why-i-am-translating-rozka-korczaks-vilna-ghetto-memoir/26294

Says Evaldas Balciunas of Siauliai: “The Vilna Ghetto memoir of Rozka Korczak-Marle . . . is unfortunately completely unknown to Lithuanians today. I have therefore decided to translate the book into Lithuanian.”

It is most powerful when Lithuanians themselves stand up and speak out. Let’s hope the examples set by courageous pioneers for truth and openness will trigger others to follow their lead. The country will benefit enormously from the sound of enlightened voices.

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - (0) Comment

Save Our Lady of Vilnius (and our office view)!

By Noreen Malone, New York Magazine

The Lady of Vilnius in New York.

Perhaps you, Intel reader, work in an office. Perhaps sometimes, as much as you might love your job, you stare at the taupe walls of your cubicle, the industrial white paint on the walls, and your standard-issue Dell desktop and think about how it's all a little soul-crushing. Just fluorescent lights and vaguely tacky carpeting, day after day after day, until you eventually die or possibly marry rich or get a job somewhere like Google or the Barneys window-design department. But maybe there is one bright spot in your Office Modern visual palette: a window with sunlight, and a view that you have come to treasure.

Outside our windows here at New York HQ, our view is a jumble of billboards for storage services, sturdy city trees, glassy Soho high-rises, and cars headed for the Holland Tunnel. But also, unexpectedly and charmingly situated in the middle of all that bustling 2011-ness, there's a modest sand-and-weathered-copper church, Our Lady of Vilnius. It has survived assaults from Hellboy and other assorted demonic beings, but now Vilnius faces Judaslike betrayal from a trusted authority: the Archdiocese of New York.

The church, which was built a century or so ago by Lithuanian immigrants, was closed in 2007 by the archdiocese, along with other low-attendance parishes, as a cost-saving measure. Vilnius apparently has a roof that would cost a bundle to fix. But the Vilnius community — which now includes more recent waves of immigrants from places like Portugal and the Philippines — turned out to be more vibrant than expected.

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

IKEA to open in Lithuania!

- Posted by - (2) Comment

![]()

IKEA, which runs an international network of furniture and household stores, announced today its plans to open a store in Vilnius which will be the first IKEA outlet in the Baltic States. The store, to be built in the vicinity of the Vilnius International Airport, is to be erected by Felit, an Icelandic company operating through a franchise agreement with IKEA.

The investment project, valued 107 million euros, has been supported by the Lithuanian Ministry of Economy and Invest Lithuania, a public agency which offers free consulting services to foreign investors.

“Large international companies invest when they see tangible benefits for their business. IKEA’s decision means that the government has followed the right path in order to improve the business environment and ensure stability in several recent years,” said Rimantas Žylius, the Minister of the Economy.

The fact that IKEA has developed a viable network of partners and suppliers in Lithuania over the past decade was an important argument in encouraging IKEA to open its store in Vilnius, according to Mantas Nocius, General Manager of Invest Lithuania.

“Expanding presence in Lithuania through opening a store looked like a natural next step. This idea has begun materialising about one and a half years ago. We did our best to prop up this project and have the deal done,” Nocius said.

IKEA, which currently runs a network of 325 stores worldwide, is one of the largest furniture and household retailers. Its projected sales are to stand at 26 billion euros in 2011.

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - (0) Comment

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - (0) Comment

“Reconstructing our Lithuanian family”

at the Lithuanian Embassy in the U.S.

First joint Hanukkah –

Lithuanian Kucios Party

One bishop, four rabbis.

On Sunday December 11 at 2 pm, four Rabbis, a Bishop and members of the local Jewish and Lithuanian communities celebrated together at the first annual joint Hanukkah and Lithuanian Kucios Party at the Embassy of the Republic of Lithuania in the U.S.. The joint party was hosted by The Jewish Lithuanian Heritage Project and The Lithuanian-American Community of D.C. at the invitation of His Excellency Ambassador Zygimantas Pavilionis. The celebration is part of The Sunflower Project, an international effort to bridge the Jewish and Lithuanian communities through open dialogue, youth exchanges and shared cultural events.

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - (3) Comment

“Reconstructing our Lithuanian family”

at the Lithuanian Embassy in the U.S.

First joint Hanukkah –

Lithuanian Kucios Party

One bishop, four rabbis.

On Sunday December 11 at 2 pm, four Rabbis, a Bishop and members of the local Jewish and Lithuanian communities celebrated together at the first annual joint Hanukkah and Lithuanian Kucios Party at the Embassy of the Republic of Lithuania in the U.S.. The joint party was hosted by The Jewish Lithuanian Heritage Project and The Lithuanian-American Community of D.C. at the invitation of His Excellency Ambassador Zygimantas Pavilionis. The celebration is part of The Sunflower Project, an international effort to bridge the Jewish and Lithuanian communities through open dialogue, youth exchanges and shared cultural events.

Ambassador Pavilionis welcomed the crowd of over 130 people, “Lithuania has a rich history of many peoples and cultures, and today we are reconstructing our Lithuania family.”

Diana Vidutis, the President of The Lithuanian-American Community of D.C. introduced the children from the Lithuanian School, Kristijono Donelaičio Lituanistinė Mokykla of Washington, D.C., who performed Lithuanian Christmas songs and shared their Kucios traditions. Children from Congregation Har Shalom and other local synagogues performed short readings, taught the game of dreidel (spinning tops) and conducted a menorah lighting ceremony, central to the celebration of Hanukkah all over the world. Rabbi Elhanan "Sunny" Schnitzer, Spiritual Leader of Bethesda Jewish Congregation led the entire group in a Hanukkah sing-a-long.

Rabbi Deborah Bodin Cohen, the Director of Congregational Learning at Congregation Har Shalom, read from her newly published children’s Hanukkah book, “Engineer Ari & the Hanukkah Mishap.”

The Most Reverend Bishop Barry C. Knestout of the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Washington and Rabbi Adam Raskin, Spiritual Leader of Congregation Har Shalom, jointly blessed the meal of traditional Hanukkah treats of latkes, doughnuts and gelt (chocolate coins) and Lithuanian Kucios. Bishop Knestout, explained his Lithuanian roots go back to his great grandfather who came from Lithuania to America.

Also attending were Rabbi Ken Cohen, Founder of the Vine and Fig Project, and Arthur Berger of the US Holocaust Memorial Museum.

The Founder of the Sunflower Project, Harley Felstein, summed up the afternoon, “The First Annual Joint Hanukkah Kucios Party was a great success in bringing together the Jewish people and the Lithuania people in a united, positive celebration, deepening the roots of the Sunflower Project.”

Harley Felstein’s son, Benjamin, presenting a dreidel to Ambassador Pavilionis.

For more information:

Adrienne Oleck aoleck@comcast.net or 240-305-7831

Harley Felstein harleyfelstein@yahoo.com or 503-421-2848

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

Graves matter to Litvaks

- Posted by - (0) Comment

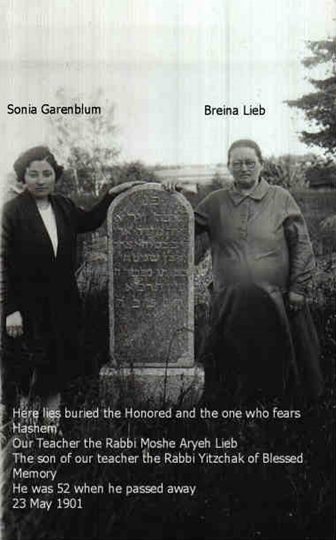

In Janjelgava in Latvia, I found the grave of my Great-Grandfather, it was shattered into thousands of pieces, today it appears in its original state after a complete re-build and restoration to what it would have been when my Grandmother and her siblings would have had it constructed.

Author: Grant Arthur Gochin, Los Angeles, California, USA.

I document my family to the 1700’s in Papile, Akmene District in Lithuania. Jews have lived in Lithuania around 700 years, it is possible that my family has been Lithuanian since the 1300’s. A prerequisite for any Jewish settlement is that a cemetery be built to bury the dead, and so, after 700 years, Lithuania holds many hundreds of Jewish cemeteries, and in all likelihood, there are thousands that had the name Gochin that were buried in the vicinity of Papile.

A religious requirement and a community requirement of Jews is that they maintain and honor the cemeteries of their ancestors, and so, throughout the world where Jews live, one can see clean and neat cemeteries where descendants honor their ancestors. This is very similar to the Lithuanian tradition of All Souls Day where families visit and honor, and remember the graves of their ancestors.

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

Graves matter to Litvaks

- Posted by - (12) Comment

In Janjelgava in Latvia, I found the grave of my Great-Grandfather, it was shattered into thousands of pieces, today it appears in its original state after a complete re-build and restoration to what it would have been when my Grandmother and her siblings would have had it constructed.

Author: Grant Arthur Gochin, Los Angeles, California, USA.

I document my family to the 1700’s in Papile, Akmene District in Lithuania. Jews have lived in Lithuania around 700 years, it is possible that my family has been Lithuanian since the 1300’s. A prerequisite for any Jewish settlement is that a cemetery be built to bury the dead, and so, after 700 years, Lithuania holds many hundreds of Jewish cemeteries, and in all likelihood, there are thousands that had the name Gochin that were buried in the vicinity of Papile.

A religious requirement and a community requirement of Jews is that they maintain and honor the cemeteries of their ancestors, and so, throughout the world where Jews live, one can see clean and neat cemeteries where descendants honor their ancestors. This is very similar to the Lithuanian tradition of All Souls Day where families visit and honor, and remember the graves of their ancestors.

Jews and Lithuanians lived in mostly peaceful coexistence for centuries, when Vilnius was known as the “Jerusalem of the North” and hundreds, if not thousands of Jewish cemeteries existed in the lands of Lithuania.

In 1915, Jews of the Baltics were deported into the Russian territories of the Ukraine and Belarus. An estimated 100,000 Jews of Baltic origin died of starvation and typhus in faraway foreign lands, including the majority of my family. At that time, almost no records remain of their deaths or burials, and 100,000 Baltic Jewish souls have largely been forgotten. From 1919 Jews were allowed to return to Lithuania, and populations began to regenerate. Burials were recorded, cemeteries restored and communal life re-established. Some of my relatives emigrated to South Africa, and new burial grounds were established.

The Holocaust murdered 96.4% of remaining Jews on Lithuanian soil. From a pre-World War 2 population of about 240,000 Jews, an estimated 3,500 Jews now live in Lithuania, a tattered remnant of the great community of learned thinkers and progressives that once inhabited our ancient homelands. For many, the Survivors were the only remnant of their families, all history having been wrenched away from them when their elders and teachers were so brutally murdered. During the Holocaust hundreds of Jewish cemeteries were destroyed, stones used for building materials, or just wanton destruction. The end of the war brought Soviet occupation, where Jewish cemeteries were further deliberately desecrated and destroyed, and most of the remainder were taken back by nature, the great population that populated Lithuania for 700 years was to be forcefully forgotten, and all signs of their presence to be eradicated, so that the last wafting memories of their existence could be destroyed over time.

My beloved Grandfather tried many times to return to Lithuania after the war, but the Soviets barred South African citizens from entering Lithuania, and so, in 1984 he went to his death without ever having been able to visit the graves of his family. The task fell to me to honor my ancestors.

Research showed that 75% of the land of the Jewish cemetery in Papile was now covered with apartment buildings; not a single stone remained standing for a single relative whose memory was now erased from Papile where documents prove at least 250 years of residence. In 2005, I put up one new stone to memorialize all Gochins that must be buried in that cemetery.

My Maternal Grandmother believed she had been born in Raguva (in fact she was born in Birzai) but given the deaths of both parents during the deportations when she was a young child and the removal of all memory, she had no facts. Research discovered the following photograph from the Raguva Jewish cemetery. I went looking….

After the round up and murder of the Jews of Raguva, local villagers used the gravestones for building material. Stories then spread of “rich Jews” that had been buried with gold fillings, and so much of the remainder of the cemetery was destroyed as people dug for gold from dead bodies. Today, few stones remain. This is not unusual for any Jewish Cemeteries in Lithuania.

Repeated visits to Raguva failed to restore the cemetery, applications for permission went unanswered and frustration set in. Municipalities in Lithuania are responsible for maintenance of Jewish Gravesites and so Governmental pressure was inconsequential. Restoration may ONLY be done with the cooperation of local officials, and regulation requires that the cemetery soil not be moved, as this would be desecration.

I strongly believe that their colorful lives, their contributions to humanity, their vibrant and learned culture should not be forgotten. Their memory is a blessing, their loss will never be able to be recovered and Lithuania will always be less than it could have been without their presence. To allow their lives to be forgotten is a tragedy none should tolerate. We, who are the descendants of those few that survived, owe it to those who had no surviving descendants to remember them, to clean their cemeteries and acknowledge their existences.

During my journeys and efforts, I made two friends, Sergey Kanovich, Public Relations advisor to the Lithuanian Jewish Community, and son of Grigor Kanovich (Past Chairman of the Lithuanian Jewish Community), and Alexander Avramenko, who believe and think similarly to myself, who value our heritage and our roots and who hold memory as a treasure for the ages. Together we have worked on multiple cemeteries in Lithuania (as can be seen on http://litvak-cemetery.info/index.php?lang=en

Between us, we have built a network on the ground in Lithuania that now know how to navigate the system of municipalities, have volunteers in place to perform the physical work that is needed, and the historians to document information that can be gleaned from the stones. We are connected into the international genealogical Associations that will distribute the information (for free) to any interested people. A non-profit status has now been granted to Maceva in Lithuania. An International Board has been built comprised of historians, government officials and those that care about maintaining and recording the memory of our roots, so that when Jews talk about heritage, we can show our children and grandchildren tangible signs of the greatness of our history, and the combined efforts and travails it took to bring the current generation to the place of safety and position we may now hold.

We, who are not subject to deportations or pogroms for our Jewish birthright, cannot make things better for those that were so badly treated, but we can bring them honor, dignity and remembrance, and give them thanks for where we are today.

Grant Gochin sits on the International Advisory Board of http://litvak-cemetery.info/index.php?lang=en

He is President of www.GAAWS.com and serves as the Honorary Consul of Togo in California, and is Secretary of the Executive Committee of the Los Angeles Consular Corps.

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - (2) Comment

MACEVA - מצבה

http://www.litvak-cemetery.info/

MACEVA (מצבה Matseyva in Hebrew) - In Hebrew language means 'gravestone'.

Lithuania is often referred to as the cradle of Eastern European Jewish culture where a large vibrant Jewish community once flourished. This community’s rich cultural and religious traditions vanished during the Holocaust. According to various estimates, in pre-war Lithuania there were between 200-240 Jewish cemeteries. Today, the majority of them are forgotten and neglected. New buildings were built on top of or next to some old cemetery sites, and gravestones have often been used as construction materials.

Time ruthlessly ravages old graves. These sites often become the target of attacks by vandals. Because of lack of funds and initiative, old Jewish cemeteries are quickly disappearing and the memories of Litvaks (Lithuanian Jews) who are buried there will disappear as well. In Lithuania we walk on the streets paved by Litvaks, we pass houses where they lived, schools where they learned, synagogues where they prayed, theaters where they preformed … a land where they thrived..

Old Jewish cemetery in Lithuania is not simply a burial place. It is part of Lithuanian history and culture.

'MACEVA' is a non-profit organization, which aims to preserve signs of old Jewish cemeteries, for the future generations in Lithuania and the diaspora.

Goals of MACEVA are:

- Collect, catalogue and publicize information about all the pre-WWII Jewish cemeteries in Lithuania. Document through photographs all remaining tombstones in all Jewish cemeteries throughout Lithuania;

- Translate all legible inscriptions from the gravestones and post this information on our website, so that everybody can get a list of cemeteries or a burial list free of charge;

- Whenever possible restore/reconstruct, or at least clean cemeteries, with the assistance of and in cooperation with local municipalities;

- Install permanent memorial plaques at Jewish cemeteries across the country with information about the site and the community;

- Raise awareness among local communities about the Jews who used to live in the neighbourhood and seek their support to look after Jewish cemeteries.

Living people deserve as much respect as they show not to only to those alive, but dead too. Memory can not be nameless.

Realizing MACEVA's goals depends not only on us, but also on you!

Therefore, we welcome everybody’s support - individuals, businesses, governments and non-governmental organizations.

If you are looking for the graves of your ancestors, please click on the "List of Cemeteries" in menu on the left. Here you will find links to the list of cemeteries by county.

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - (0) Comment

MACEVA - מצבה

http://www.litvak-cemetery.info/

MACEVA (מצבה Matseyva in Hebrew) - In Hebrew language means 'gravestone'. 'MACEVA' is a non-profit organization, which aims to preserve signs of old Jewish cemeteries, for the future generations in Lithuania and the diaspora.

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

VilNews e-magazine is published in Vilnius, Lithuania. Editor-in-Chief: Mr. Aage Myhre. Inquires to the editors: editor@VilNews.com.

Code of Ethics: See Section 2 – about VilNews. VilNews is not responsible for content on external links/web pages.

HOW TO ADVERTISE IN VILNEWS.

All content is copyrighted © 2011. UAB ‘VilNews’.

Click on the buttons to open and read each of VilNews' 18 sub-sections

Click on the buttons to open and read each of VilNews' 18 sub-sections

.jpg)