THE VOICE OF INTERNATIONAL LITHUANIA

|

VilNews has its own Google archive! Type a word in the above search box to find any article.

You can also follow us on Facebook. We have two different pages. Click to open and join.

|

Author Archive

The first time I heard the name of Žagarė

- Posted by - (0) Comment

Žilvinas Beliauskas

By Žilvinas Beliauskas

Manager of Cultural Projects

Vilnius Jewish Public Library

The first time I heard the name of Zhagare (Žagarė) it was probably like for many Lithuanian kids related to cherries – Zhagre cherrys. Big and juicy ones. There were some of such trees in my parents’ orchard. Zhagare liqeuer came later. Maybe even later than mom‘s notice about St. Barbara of Zhagare (Barbora Žagarietė) from 17th century, though not beatified yet but very revered in Samogitia (Žemaitija) as a real saint in charge of many miraculous healings. And that was it for many years until it turned out that the family of my wife comes from Zhagare. During the first walking tour with her I enjoyed marvelous streets of wooden houses along river Shvete, radiating strange and sadly atractive kind of romantic atmosphere of brick houses around the Central Square. The architecture prompted straightforwardly that they used to belong to Jews and association with the direction sign by the road at the entrance to Zhagre showing the way to the Graveyard of the Jewish Genocide Victims made this atmosphere still blurry ghostly, not quite tangibly yet but bringing a distant smell of its “echos and absences” to use Roger Cohen phrase in his letter to the forthcoming event this Friday.

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

Echos and absences

- Posted by - (0) Comment

Roger Cohen

By Roger Cohen,

Columnist, International Herald Tribune and New York Times

I look forward with considerable emotion to returning to Zagare for the unveiling of a plaque that will commemorate the slaughter of more than 2,250 Jews in the town on October 2, 1941. More than three score years and ten have gone by since that mass murder without full acknowledgment of its scope. The men, women and children taken from the main square into the woods to be killed have remained anonymous, mere shadows, their fates at first concealed by Soviet political calculation and taboos, and then only falteringly recognized after Lithuania gained independence in 1990. I do not know the Jews who were killed but I know that each of them valued life and its joys as we do, and I know that my grandmother, Pauline (“Polly”) Soloveychik would have been among them had she not left Zagare for South Africa in the early 20th Century. For me, the fate of the Zagare Jews is personal.

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - (0) Comment

Zagare Cherry Festival

„You can‘t fudge the history“

12–15th of July 2012

Zagare Cherry Festival – a traditional event which helps to develop Northern Lithuania, former Semigallian territory, culture, unique and attractive image of Zagare as one of the oldest towns in Lithuania and beautiful tourism destination, promoting the development of this the former Northern Lithuanian cultural center of the eighteenth century. Cherry Festival and Zagare is an inexhaustible storehouse of knowledge, new impressions and events. Culturally crossing a couple of centuries of Zagare history, the eighth Cherry Festival will help to discover, explore and understand the uniqueness of the town. The main event of the festival, using historical materials and staged events of the past, will raise from oblivion the image of the historical market square. Although the present town and the town of those old separates only 200 years time, these "cultural centers" in Cherry Festival will be closer together than ever before. The time machine and all the characters will carry away to the past where the ancient craftsmen is working, merchants schooling, costumed waiters invite for dinner, the bagpipe and an old gramophone begin to play, still managed to play the older version of the melody than itself, which touched both young and old hearts...

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - (0) Comment

Zagare Cherry Festival

„You can‘t fudge the history“

12–15th of July 2012

Zagare Cherry Festival – a traditional event which helps to develop Northern Lithuania, former Semigallian territory, culture, unique and attractive image of Zagare as one of the oldest towns in Lithuania and beautiful tourism destination, promoting the development of this the former Northern Lithuanian cultural center of the eighteenth century. Cherry Festival and Zagare is an inexhaustible storehouse of knowledge, new impressions and events. Culturally crossing a couple of centuries of Zagare history, the eighth Cherry Festival will help to discover, explore and understand the uniqueness of the town. The main event of the festival, using historical materials and staged events of the past, will raise from oblivion the image of the historical market square. Although the present town and the town of those old separates only 200 years time, these "cultural centers" in Cherry Festival will be closer together than ever before. The time machine and all the characters will carry away to the past where the ancient craftsmen is working, merchants schooling, costumed waiters invite for dinner, the bagpipe and an old gramophone begin to play, still managed to play the older version of the melody than itself, which touched both young and old hearts...

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - (3) Comment

Visit Žagarė,

northern Lithuania,

this weekend

Former Žagarė synagogue.

INVITATION TO A VERY SPECIAL EVENT IN ŽAGARĖ

Under the initiative and leadership of a Lithuanian activist Valdas Balčiūnas, A MEMORIAL PLAQUE TO COMMEMORATE THE ZAGARE JEWISH COMMUNITY will be unveiled. The ceremony coincides and may be considered to be taking place in the context of ZAGARE CHERRY FESTIVAL which will be held in July 12-15. The plaque will be in English, Lithuanian, and Yiddish. Here is what the English version will say:

|

For hundreds of years Žagarė (in Yiddish — Zhager) had been home to a vibrant Jewish community. Zhager’s marketplace had many Jewish shops and was a center of commerce for merchants from here and a range of other towns. Many of their shops surrounded this square. Zhager was also famous for its many Hebrew scholars, the “Learned of Zhager”. German military occupiers and their Lithuanian collaborators brought the region’s Jewish men, women, and children to this square on October 2, 1941. Shooting and killing of the entire Jewish community of Zhager began here and continued in the forests nearby. About 3,000 Jewish citizens were killed.

|

The festival begins on July 12, 2012. Here are some highlights of Jewish interest:

- Dedication of the memorial plaque -- Friday July 13 at 1600 in the Zagare Town Square

- "From the History of the Shtetl"– a presentation, exhibition, and concert organized by the Joniskis Municipality Museum -- Friday July 13 at 1700 at the Zagare Culture Centre

- Baltic senior football (soccer) competition including the Makabi team from Vilnius – Saturday July 14 at 1300.

Please let us know if you are planning to attend. We look forward to seeing a strong representation of descendants of the former Jewish community of Zagare. After the official events there will be a FRIDAY EVENING GATHERING AND 'KABBALAT SHABBAT' FOR VISITORS. If you wish to be invited to this please let us know.

For more information please contact any of the following:

UK - Joy Hall (joy@joymaynard.myzen.co.uk

LITHUANIA -Valdas Balciunas (valdas@me.com)

U.S. - Cliff Marks (c.v.marks@att.net)

ISRAEL - Sara Manobla (manobla@netvision.net.il)

The first time I heard

the name of Žagarė

Žilvinas Beliauskas

By Žilvinas Beliauskas

Manager of Cultural Projects

Vilnius Jewish Public Library

The first time I heard the name of Zhagare (Žagarė) it was probably like for many Lithuanian kids related to cherries – Zhagre cherrys. Big and juicy ones. There were some of such trees in my parents’ orchard. Zhagare liqeuer came later. Maybe even later than mom‘s notice about St. Barbara of Zhagare (Barbora Žagarietė) from 17th century, though not beatified yet but very revered in Samogitia (Žemaitija) as a real saint in charge of many miraculous healings. And that was it for many years until it turned out that the family of my wife comes from Zhagare. During the first walking tour with her I enjoyed marvelous streets of wooden houses along river Shvete, radiating strange and sadly atractive kind of romantic atmosphere of brick houses around the Central Square. The architecture prompted straightforwardly that they used to belong to Jews and association with the direction sign by the road at the entrance to Zhagre showing the way to the Graveyard of the Jewish Genocide Victims made this atmosphere still blurry ghostly, not quite tangibly yet but bringing a distant smell of its “echos and absences” to use Roger Cohen phrase in his letter to the forthcoming event this Friday. Later I asked my wife’s grandmother, who is 84, weather it had been difficult during the Second World War. She said, - ouch, we did not see much of the war here; we were made to work of course for the war and got some food supplies but the most terrible thing was about Jews that they were killed. She remebers a German officer commanding from the balcony for the collaborators in the Central Square to start the massacre of the crowd herded into the central area. She was just waving her hands – oh oh oh… Layers of silence or surpressed whispers with heavy locks on wording went afterwards. Maybe or hopefully, or at least some “dutiful nod to shadows” was made by some (R. Cohen again). It’s a riddle for the younger generations. Perhaps to the older ones too.

It’s a long story and let those who know better to do the healing practice for everybody to speak the truth. Say for Rose Zwi, a writer, who has her ancestors in that mass grave. Her book the “Last walk in Naryshkin Park” to my mind had to be translated immediately after it was published in 1997. Today she is back to Lithuania to celebrate a sign of memory awakening little by little – a special plaque to be unveiled on July 13, 2012 in Zhagare Central Square. There are many other coming to the event from all over the world. R. Zwi made it from Australia. High guests will range from the Ambassador of Israel to film producer and director from Australia Rod Freedman, who made a documentary “Uncle Chatzkel“, „International Herald Tribune“ and “New York Times” columnist Roger Cohen (see his letter below), Joy Hall, the creator of the Lithuanian Link, Cliff Marks, the creator of ShtetLinks and to many others. Rose’s friend Sara Manobla came from Israel, her family has roots in Zhagare. And she she is one of those lucky few surviving Zhagare Jewish offsprings but not the only one to be present on that day.

There were very pleasant moments when on her way to Zhagare Rose Zwi and her friend Sara Manobla in companion of Rose’s local cousin Fryda visited the Vilnius Jewish Public Library on July 09, 2012. Her two presented books, “Last Walk in Naryshkin Park” and “Once Were Slaves” (about the Perlov family fate in Soviet gulags), with authors signatures will be of very high value for the library. The guests were very fond to find out the story of this new library to appear in Vilnius, its initator Wyman Brent and the role it is seeking to play in complex cutural polylog. Luckily, Fryda immediately came accross a book on the shelves “Life of the Jews of Joniškis region during the inter-war period (1918-1940)” where they found many familiar names and faces in the photos. It seemed the conversation could have lasted for hours and hours and many touched upon and vividly started stories remained to be continued. Everything was possible due to their friend and host Julius Bieliauskas who made all the linking, introducing and provided safe transportation. See more of these moments and see everybody in Zhagare.

Echos and absences

Roger Cohen

By Roger Cohen,

Columnist, International Herald Tribune and New York Times

I look forward with considerable emotion to returning to Zagare for the unveiling of a plaque that will commemorate the slaughter of more than 2,250 Jews in the town on October 2, 1941. More than three score years and ten have gone by since that mass murder without full acknowledgment of its scope. The men, women and children taken from the main square into the woods to be killed have remained anonymous, mere shadows, their fates at first concealed by Soviet political calculation and taboos, and then only falteringly recognized after Lithuania gained independence in 1990. I do not know the Jews who were killed but I know that each of them valued life and its joys as we do, and I know that my grandmother, Pauline (“Polly”) Soloveychik would have been among them had she not left Zagare for South Africa in the early 20th Century. For me, the fate of the Zagare Jews is personal.

When I visited the village for the first time in November last year, as I began research on a family memoir, the last Jew in Zagare, Isaac Mendelson, has just died. So ended a presence that began in the 16th century. In 1897, three years after my grandmother’s birth, there were 5,443 Jews in Zagare. Mendelson, a community of one, used to stand on the corner of the market square with his dachshund, Chipa. He would recall the times after the war when he was a goalkeeper for the local soccer team. Never did he talk about the day Nazis and their Lithuanian collaborators murdered the Jews, including members of his own family.

Zagare is a place of echoes and absences, my grandmother’s being but one. It hovers over loss, a void that whispers. I came back to see what might have been. Next to a bridge on the Svete I noticed a plaque commemorating the death on June 29, 1941, of Jonas Bavanauskas, who was “killed defending his homeland.” He died a few days after the Nazis invaded Lithuania and embarked on one of the swiftest mass murders of a nation’s Jews in the entire European I extermination program, one largely completed before the gassing facilities of industrialized Jewish annihilation were in place.

Bavanauskas, who merits a plaque, was not a Jew. Yet he alone is identified in Zagare. He is thereby accorded a presence that feels like more than a dutiful nod to shadows. He lived, he felt, he resisted, he died. His name is there, legible. It is there at the center of a town that lies between two disused Jewish cemeteries, one in the “new” and one in the “old” district. In the cemeteries gravestones lurch, lichen advances and Hebrew inscriptions crumble or fade into illegibility. Fragments of letters recall Anna Akhmatova’s words in Requiem, “I’d like to call you all by name, but the list has been removed and there is nowhere else to look.”

The plaque to be unveiled on July 13, 2012, will go some way toward giving the people of Zagare a place to look to understand the history of their town. It is past time for that.

|

|

Roger Cohen joined The New York Times in 1990. He was a foreign correspondent for more than a decade before becoming acting foreign editor on Sept. 11, 2001, and foreign editor six months later. Since 2004, he has written a column for The Times-owned International Herald Tribune, first for the news pages and then, since 2007, for the Op-Ed page. In 2009 he was named a columnistof The New York Times. Mr. Cohen has written “Hearts Grown Brutal: Sagas of Sarajevo” (Random House, 1998), an account of the wars of Yugoslavia’s destruction, and “Soldiers and Slaves: American POWs Trapped by the Nazis’ Final Gamble” (Alfred A. Knopf, 2005). He has also co-written a biography of General Norman Schwarzkopf, “In the Eye of the Storm” (Farrar Straus & Giroux, 1991).

|

|

Zagare Cherry Festival „You can‘t fudge the history“

Zagare Cherry Festival – a traditional event which helps to develop Northern Lithuania, former Semigallian territory, culture, unique and attractive image of Zagare as one of the oldest towns in Lithuania and beautiful tourism destination, promoting the development of this the former Northern Lithuanian cultural center of the eighteenth century. Cherry Festival and Zagare is an inexhaustible storehouse of knowledge, new impressions and events. Culturally crossing a couple of centuries of Zagare history, the eighth Cherry Festival will help to discover, explore and understand the uniqueness of the town. The main event of the festival, using historical materials and staged events of the past, will raise from oblivion the image of the historical market square. Although the present town and the town of those old separates only 200 years time, these "cultural centers" in Cherry Festival will be closer together than ever before. The time machine and all the characters will carry away to the past where the ancient craftsmen is working, merchants schooling, costumed waiters invite for dinner, the bagpipe and an old gramophone begin to play, still managed to play the older version of the melody than itself, which touched both young and old hearts... Murmurous town square - a living, historical events and theatrical improvisation spontaneous, sudden blurred everyday life will join with music, art, literature, poetry, dance to a whole. This staged marketplace will present the official Zagare old town square opening. A four-day event will be complemented by various exhibitions, horse racing, football competitions, attractions and the other surprises. Again and again, each time differently in the openness and freedom of expression blowing programme, which will involve different kinds of artists, everybody came to the Cherry Festival will be able to find something lovely for his eye and heart. Zagare will be waiting for the guests with open arms this year too. At least for a few days to come to Lithuania's oldest city - Zagare is really worth, because historical memory will dominate here. remigijus.lt© 2012 vysniufestivalis.lt |

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

People who think that those who left Lithuania had a comfortable life, are sadly mistaken

- Posted by - (6) Comment

Rūta Bražiūnienė

HEALING WOUNDS BETWEEN LT-AMERICANS AND HOMELAND LITHUANIA

Our debate topic in VilNews Forum, with the above headline, has now attracted more than 200 comments. Here is one of the posts, written by Rūta Bražiūnienė:

While I noticed that the above 156 comments argue about passports, I just have an issue with the first post, that I have not noticed be addressed, yet. "Many here in Lithuania still believe that those who left, whether for economic or political reasons, had very comfortable lives compared to those who stayed behind and had to fight through several decades of inhuman oppression and abuse by the Soviet occupiers."

I totally assume, based on my own previous experience, that people who think that those who left Lithuania had a comfortable life, are sadly mistaken. My parents fled within hours of occupation. They saw close relatives, neighbors, friends be killed by Soviets. They fled to save their lives.

It's hard not to generalize, as we all seem to do that quite well. That generation, who had to make decisions to flee, thought that they would be back in days. Then weeks. Then months. And before they knew it, years passed. They lived in DP (displaced person) camps. There was no luxury there.

The horrors of the Soviet oppressors made them band together, to lobby their politicians, start Lithuanian schools, cultural dance and song groups, and anything they could do to keep the memory of their Lithuania alive. (Estonians and Latvians were in the same situation).

I can vouch for many in my generation, that we were shocked at the devastation of the Baltic lands when we visited decades later. We had heard of a paradise Lithuania our entire lives, and visiting it - was... well, a rude awakening.

Sure, they over-generalized, too. But we banded together, Baltics displaced by WWII all over the world, and continued our parents' traditions, and did what we could to help free the Baltic States. Our parents never had it easy. They worked two jobs, not in their educated field, and suffered a different way, than their brothers and sisters who remained. They sent most of their pay, clothes, food, just to help those whom they could.

Luckily, some made a good life for themselves. But many more tried what they could just to make ends meet.

So when Lithuania was freed, imagine our surprise when there is this almost hatred for those who left. We were just happy to be reunited, or for others, seeing the relatives our parents no longer could.

Nobody had it easy. I wish that those left to grow up under Soviet rule would understand that.

The only thing that would have happened, had our parents not fled, is that they, too, would have been killed by the Soviets.

With all of this contempt, crime, and mostly - lack of acceptance - who would want to move back, only to be labeled, mugged, robbed, humiliated, etc? It's not easy for anybody, folks. We all agree that the Soviets destroyed families, hope, land, etc. What good does arguing about who had it worse do?

We need to move forward. We can't change the past. So all we can do is work towards one goal of acceptance. Please.

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - (0) Comment

Healing wounds between

LT-Americans and homeland Lithuania

Our debate topic in VilNews Forum, with the above headline, has now attracted more than 200 comments. Here is one of the posts, written by Rūta Bražiūnienė.

By Rūta Bražiūnienė

While I noticed that the above 156 comments argue about passports, I just have an issue with the first post, that I have not noticed be addressed, yet. "Many here in Lithuania still believe that those who left, whether for economic or political reasons, had very comfortable lives compared to those who stayed behind and had to fight through several decades of inhuman oppression and abuse by the Soviet occupiers."

I totally assume, based on my own previous experience, that people who think that those who left Lithuania had a comfortable life, are sadly mistaken. My parents fled within hours of occupation. They saw close relatives, neighbors, friends be killed by Soviets. They fled to save their lives.

It's hard not to generalize, as we all seem to do that quite well. That generation, who had to make decisions to flee, thought that they would be back in days. Then weeks. Then months. And before they knew it, years passed. They lived in DP (displaced person) camps. There was no luxury there.

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - (0) Comment

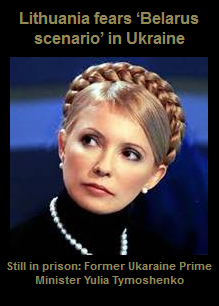

Russia regaining influence over the is possible in Ukraine

Darius Semaška

If the EU plays its cards badly, a "Belarus scenario" in which Russia would regain influence over the former Soviet Republic is possible in Ukraine, Darius Semaška, a chief government advisor for Lithuania, told journalists yesterday (10 July). EurActiv reports from Vilnius.

“Unfortunately, the developments in Ukraine are not those that we wanted to see,” Semaška said, speaking to a small number of Brussels journalists invited for a press trip to Vilnius.

Semaška, who leads the foreign policy group advising Lithuania's president, evoked a variety of topics, including the EU's sensitive relations with Ukraine ahead of it parliamentary elections to be held on 28 October.

Speaking of Ukraine, the Lithuanian government advisor referred in particular to the “selective justice” against political opponents and the conviction and imprisonment of former Prime Minister Yulia Tymoshenko for abuse of office.

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

![]()

Lithuania’s opposition, the Social Democratic Party, leads in opinion polls three months before the general election, according to a survey by Spinter Tyrimai for online news service Delfi.

The Social Democrats received 14.2 percent support in a survey conducted June 15-22, Delfi said on its website. Two other opposition parties, the Labor Party and Order & Justice, ranked second and third with 13.3 percent and 11.2 percent, respectively. Prime Minister Andrius Kubilius’ Homeland Union placed fourth with 8.5 percent support, the survey showed.

The poll of 1,008 eligible voters, had a margin of error of 3.1 percentage points. Lithuania will hold the general election on Oct. 14.

(Bloomberg)

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

Voters see social democrat Algirdas Butkevičius as best candidate for Lithuania’s prime minister

- Posted by - (0) Comment

![]()

Algirdas Butkevičius

Picture: Irmanto Gelūno/15min.

About one sixth of Lithuanian voters see Algirdas Butkevičius, leader of the opposition Social Democrats, as the best candidate for the post of prime minister, shows a poll published in delfi.lt.

Some 16.1 percent of respondents said Butkevičius was best suited for the position, ousting the long-time favorite Irena Degutienė of the ruling Homeland Union – Lithuanian Christian Democrats (conservatives) from the top of the list. According to the poll carried out by Spinter Tyrimai (Spinter Surveys) in June, Labor Party's chairman Viktor Uspaskich headed the list in April.

In the June survey, 16.1 percent said Butkevičius would best fill the PM post, while Degutienė and Uspaskich were supported for the position by 15.7 percent and 14.4 percent of those polled, respectively. In May, Degutienė enjoyed support of 15.9 percent, Butkevičius 14.5 percent, and Uspaskich 13.3 percent.

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - (0) Comment

A new film, Land Of Songs, will show the Lithunian dainos (songs) as living, breathing stories, deeply rooted in their natural surroundings, daily routines, and rich histories.

Močiutės dainos

Land of Songs Director Aldona Watts with the močiutės: Stasė Bogušienė,

Jonė Dvareckienė, Marytė Klimavičienė, and Pranė Barysienė.

Hello and Sveiki!

My name is Aldona. I’m a Lithuanian-American multimedia producer from San Francisco, living and working in Brooklyn. This project has been a dream of mine for so long now that I’m thrilled to finally make it happen!

It all began seven years ago. My family and I visited Lithuanian friends in the village of Puvočiai, and they invited their neighbors, the močiutės (or "little grandmas"), over to sing for us. These močiutės, they told us, were the last generation in a long line of traditional folk singers with ancient roots.

At twilight we laid tables under the trees with food and drink. I barely noticed the faint sound of voices weaving through the forest, until they mounted to a loud front of song. And then I saw them: a small herd of hunched figures making their way towards us, their white headscarves bobbing through the trees.

The songs were at once melancholy and joyful; the hauntingly beautiful harmonies seemed from another world. After each song, the women’s wrinkled faces cracked into wide smiles, and the ghostly echo of the voices ringing through the trees was replaced by raucous cackling.

When it was time to say goodbye, the močiutės left as they came, singing all the way. Long after they disappeared, their voices remained.

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - (1) Comment

A new film, Land Of Songs, will show the Lithunian dainos (songs) as living, breathing stories, deeply rooted in their natural surroundings, daily routines, and rich histories.

Močiutės dainos

Land of Songs Director Aldona Watts with the močiutės: Stasė Bogušienė,

Jonė Dvareckienė, Marytė Klimavičienė, and Pranė Barysienė.

Hello and Sveiki!

My name is Aldona. I’m a Lithuanian-American multimedia producer from San Francisco, living and working in Brooklyn. This project has been a dream of mine for so long now that I’m thrilled to finally make it happen!

It all began seven years ago. My family and I visited Lithuanian friends in the village of Puvočiai, and they invited their neighbors, the močiutės (or "little grandmas"), over to sing for us. These močiutės, they told us, were the last generation in a long line of traditional folk singers with ancient roots.

At twilight we laid tables under the trees with food and drink. I barely noticed the faint sound of voices weaving through the forest, until they mounted to a loud front of song. And then I saw them: a small herd of hunched figures making their way towards us, their white headscarves bobbing through the trees.

The songs were at once melancholy and joyful; the hauntingly beautiful harmonies seemed from another world. After each song, the women’s wrinkled faces cracked into wide smiles, and the ghostly echo of the voices ringing through the trees was replaced by raucous cackling.

When it was time to say goodbye, the močiutės left as they came, singing all the way. Long after they disappeared, their voices remained.

At the time, my own beloved grandmother had recently passed away. She had been a master storyteller, and I was raised on her tales of survival as a teen fleeing war-torn Lithuania. My pain at losing her was compounded by the realization that I had also lost her stories. I felt I hadn’t done enough to carry on the oral tradition of my own family, and I wished that I had recorded her, when I had the chance.

So when I saw the močiutės sing that night, I resolved to one day make a feature documentary film about them. After seven years, and with a little help, I will finally be able to do this.

The Land Of Songs

Puvočiai is nestled deep in the forests of a region called Dainava or “The Land of Songs,” known for its rich tradition of folk singing called the daina. Ranging from the deeply personal to the profoundly political, the many-layered dainos are woven with the memories of the souls who have lived and died in these same forests for millennia.

Remnants of the ancient pagan past remain intact in many of the dainos, and great pains were taken to preserve them throughout modern history, even as Lithuania was pummelled by wave upon wave of war and occupation. Today, many of the younger generations are leaving the villages to seek work in the cities and abroad. In Puvočiai, for the first time in history, there is no one to carry on the oral tradition of the daina.

The Močiutės

Stasė Bogušienė (b. 1935), is an outspoken and vivacious ringleader.

Marytė Klimavičienė (b. 1942) has a tough demeanor and a great wit.

Pranė Barysienė (b. 1929) is soft-spoken with a sweet nature.

Jonė (“Jonukė”) Dvareckienė (b. 1931), the tiniest of the bunch, is nonetheless the strongest voice and often leads the others in song.

Marytė Bingelienė (b. 1931) has missed recent performances and gatherings due to serious health problems.

These five women are the last living members of a group that once numbered twelve friends and family. They started singing as girls, to lighten their load while mushroom-hunting in the forests. They sang at festivities, and they sang to remember the stories of their mothers and grandmothers. Perhaps most importantly, their “siren songs” perked the ears of young men in neighboring villages. When war and repeated occupations left half the village burned to the ground, the women sang to rally their strength and ease their pain. An entire history of a nation in turmoil is chronicled in their dainos.

The Film

The objective of this film is not only to preserve the precious dainos of the močiutės - transcriptions and recordings can be found in archives throughout the country. Land Of Songs will be unique in that it will show the dainos as living, breathing stories, deeply rooted in their natural surroundings, daily routines, and rich histories. Shot in an observational style, Land Of Songs will be multilayered and poetic, like the dainos themselves.

We plan to shoot next month and finish the film this fall.

Director / Producer / Cinematographer: Aldona Watts

Local Producers: Kęstutis Nėnius, Danguolė Nėniuvienė, Ingrida Nėniuvienė, Motiejus Nėnius

Producer / Production Sound Mixer: Julian Watts

Producer: Matthew Shorr

Local Production Coordinator: Algimantas Kazlauskas

Sound Design: Aldona Watts in collaboration with Kyle Keays Hagerman

Land Of Songs is a true labor of love, and its success relies on friends, collaborators, and community members who are willing to help out in any way they can. I am keeping the budget as tight as possible, but I know that the story I have to tell is priceless. I also know that it has to be told now, before it’s too late.

How Kickstarter works: You can make a commitment to contribute, and you will not be charged until the deadline. If the goal is not met by the deadline, you will not be charged at all. It’s all or nothing.

Any and all funds raised will go towards production costs: video and audio equipment, travel expenses, compensating the local crew, Kickstarter fees, and Amazon processing fees.

You can also help by simply spreading the word about Land Of Songs!

www.facebook.com/landofsongs

www.twitter.com/landofsongs

www.landofsongs.com

Please contact me with any questions you may have.

Thank you and labai ačiū.

Aldona

About Aldona Watts:

Aldona Watts is a multimedia producer living in Brooklyn, New York. She graduated from New York University, and has since produced several audio documentaries. She currently manages and produces GRYC Radio, a youth radio station in Queens, and is the host/producer/engineer/DJ of a long-running weekly radio show broadcasting in New York City

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - (0) Comment

Timothy Snyder, author of Bloodlands: Europe between Hitler and Stalin:

Perhaps we can find

ways to talk to each other

A rough definition of Snyder's "Bloodlands" (by Timothy Nunan).

By Ellen Cassedy

“Even if all you want to do is understand your own group, you have no choice but to understand the history of others.”

That’s what Timothy Snyder, a professor at Yale University and the author of Bloodlands: Europe between Hitler and Stalin (Basic Books, 2010), had to say at a recent roundtable at the Tolerance Center in Vilnius.

I watched a webcast of the session – and welcomed the opportunity to revisit Snyder’s book, which I’d found challenging on two accounts.

First, immersing myself in the atrocities of the mid-20th century was no easy task. Between 1933 and 1945, in the region Snyder dubs the bloodlands – the Baltics, Belarus, most of Poland, Western Russia, and Ukraine – an unprecedented 16 million people were killed.

Second, Bloodlands required me to consider, simultaneously, the fate not only of my own group, as Snyder puts it, but also the history of others. That wasn’t easy either.

Timothy Snyder

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - (0) Comment

Timothy Snyder, author of Bloodlands: Europe between Hitler and Stalin:

Perhaps we can find

ways to talk to each other

A rough definition of Snyder's "Bloodlands" (by Timothy Nunan).

By Ellen Cassedy

“Even if all you want to do is understand your own group, you have no choice but to understand the history of others.”

That’s what Timothy Snyder, a professor at Yale University and the author of Bloodlands: Europe between Hitler and Stalin (Basic Books, 2010), had to say at a recent roundtable at the Tolerance Center in Vilnius.

I watched a webcast of the session – and welcomed the opportunity to revisit Snyder’s book, which I’d found challenging on two accounts.

First, immersing myself in the atrocities of the mid-20th century was no easy task. Between 1933 and 1945, in the region Snyder dubs the bloodlands – the Baltics, Belarus, most of Poland, Western Russia, and Ukraine – an unprecedented 16 million people were killed.

Second, Bloodlands required me to consider, simultaneously, the fate not only of my own group, as Snyder puts it, but also the history of others. That wasn’t easy either.

Timothy Snyder

As I watched the webcast, I was reminded of a beautiful summer evening at an outdoor restaurant on Pilies gatve (Castle Street) in Vilnius.

I’d traveled from my home in the U.S. to the land of my forebears in search of answers about my own Jewish family history. I wanted to understand, too, how Lithuania as a country was engaging with its Jewish family history, especially with the Holocaust. My dinner companion was a woman I’ll call Violeta, a friend of a friend, who’d volunteered to help me learn.

We sat down at a checkered tablecloth and ordered a decidedly un-Jewish meal of shrimp salad, then raised our wine glasses.

“L’chaim!” I said, offering the traditional Jewish toast. To life!

“I sveikata!” Violeta responded in Lithuanian. To health!

Growing up in the Soviet period, I asked her, what had she learned about the fate of Lithuania’s Jews during the war?

She furrowed her brow. “We learned in school that many Jews died,” she answered.

“Did you learn about the pits in the forests” – I made a digging motion with my hand – “where the Jews were shot and buried? The mass graves?”

Yes, she said, she had learned about this, too.

She looked away, then met my eyes. “But,” she said, “no one taught us in school how many Lithuanians were sent to Siberia by the Soviet power.”

Her voice grew louder. “Pregnant women and children,” she said heatedly, “they died in Siberia!” I saw that she was glaring at me, with more than a hint of accusation in her eyes.

Now it was my turn to look away. It was hard for me to listen, I found, as Violeta placed the massacre of my people alongside the suffering of hers. It was hard for me to hold in my head the reality of non-Jewish suffering side by side with Jewish suffering.

But if the conversation was not easy, I was glad to be having it.

“Each catastrophe was different,” Snyder said at the Vilnius roundtable. And “we have to accept that our memories are never going to be the same.” But studying the catastrophes that occurred in the bloodlands, and the interactions among those catastrophes, “permits us different ways, from our own different perspectives, to understand.”

If we are truly to understand history, he stressed, we cannot confine ourselves to the study of one people or one nation alone.

Instead, he said, “we have to go to the highest level, starting and ending with human beings.” Then, perhaps, we can “find ways to talk to each other in ways we haven’t before.”

ELLEN CASSEDY

Ellen Cassedy traces her Jewish family roots to Rokiskis and Siauliai. Her new book, We Are Here: Memories of the Lithuanian Holocaust, was published in March and will appear in Lithuanian soon. She lives in Washington, D.C. Visit her website at www.ellencassedy.com.

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - (1) Comment

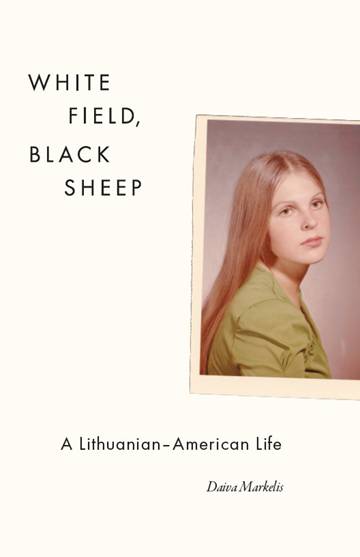

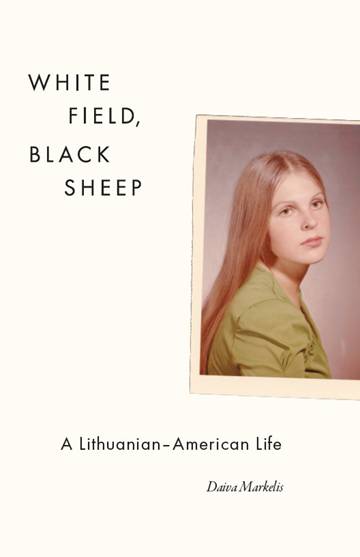

By the end of the book, author Daiva Markelis discovers

Her own way to be both

Lithuanian and American.

Daiva Markelis interviewed by Ellen Cassedy

Daiva Markelis's memoir, White Field, Black Sheep: A Lithuanian-American Life (University of Chicago Press, 2010), tells the story of her growing up as the daughter of postwar Lithuanian immigrants in the 1960's and '70's near Chicago.

The book alternates between the story of Markelis's youth – especially her struggle for cultural identity – and a series of touching later scenes with her octogenarian mother.

We see Daiva and her sister begging for real American Halloween costumes and a plastic Christmas tree, while the parents insist on speaking Lithuanian and holding true to their traditions. The descriptions of Catholic school, Lithuanian scout camp, and the family resort owned by Valdas Adamkus (who later returned to Lithuania and became its president) are tart and funny.

Markelis reveals a culture as well as a personal history. She writes affectionately about the streets, the buildings, even the tackiest billboards of her home town - while, at the same time, not shrinking from frank portrayals of racial tension and alcohol abuse. The portraits of her parents are filled with a lovely tenderness, even as she pokes fun and reveals some of their failings.

This tale of seeking cultural identity within an immigrant community comes to an uplifting conclusion. By the end of the book, Markelis has discovered her own way to be both Lithuanian and American.

Daiva, the title of your book comes from a riddle that your father posed to you when you were a child:

Black sheep on a white field;

He who knows them, leads them.

The answer is "letters on a page." You are truly a "shepherd of words" – an eloquent, elegant writer. Your love of both languages shines throughout your memoir.

Thanks for the kind words, Ellen. I'm going to start listing "shepherd" as my occupation!

I've always thought being bilingual is an advantage in so many ways. Growing up in a heavily Lithuanian culture and speaking Lithuanian as my first language have given me a different lens through which to observe American life. This has enriched me as a writer and as a human being.

My parents encouraged reading, both in Lithuanian and in English, and that has probably had the biggest impact in my wanting to be a writer and a teacher of literature.

A particularly touching part of the book, for me, was the brief section called "The Alphabet of Silence." You describe how, near the end of your mother's life, she presented you with a set of silverware that had been given to her family for safekeeping by a Jewish doctor, who then perished in the Holocaust.

You challenge your mother, asking why the fate of Lithuania's Jews was not mentioned in the community when you were growing up. On the verge of tears, she asks you to reassure her that she was a good mother.

Your handling of this scene is so subtle and beautiful that I'm reluctant to ask you to say more. But can you? Is such a conversation between mother and daughter a common one in Lithuanian-American homes?

I'm so glad you liked this section, Ellen. I wanted to write more about the many silences I experienced growing up in a Lithuanian household, but I wasn't sure how to go about this. I didn't want to alienate Lithuanian readers, many of whom are still reluctant to discuss what happened during the Nazi occupation of Lithuania. In retrospect I think I was being too subtle.

I was very close to my mother. We had many interesting conversations about a variety of topics – religion, politics, even sex. I think many Lithuanian-American daughters are close to their mothers – sometimes I think our mothers felt a bit lonely and misunderstood, and thus turned to their daughters for companionship. Of course, I thought my mother was special. She was a very outspoken, funny, and intelligent woman.

How has the book been received within the Lithuanian-American community? How do you respond to people who worry that you've shown too much dirty Lithuanian-American laundry in public?

I've received many letters, emails, and phone calls from Lithuanian-Americans saying how much they loved the book. I really wasn't expecting that! The most positive responses have come from individuals my age who grew up in Chicago or Cicero, thanking me for writing a memoir that chronicles experiences they've gone through with parental expectations, Lithuanian Saturday School, and even drinking at the bars on 69th Street in Marquette Park.

Lithuanian-Americans from an earlier generation--those whose grandparents immigrated to this country at the turn of the last century--also seem to like the book. Friends tell me that some Lithuanians are angry that I emphasize drinking so much. But I wrote what I observed and lived through, and drinking was a part of that. As I grow older I care less about what people think--I tell my students that a growing indifference to the judgments of others is one of the advantages of aging.

Also, the idea of "dirty laundry" is, to some extent, subjective. I'm sure that some Lithuanians feel I've revealed too much. Yet one friend said that I held myself back too much. And non-Lithuanian friends and critics who've read my book have remarked on how strongly the emphasis on education and culture in Lithuanian life comes through.

Books about the Lithuanian-American experience are few and far between. Why do you think this is?

There aren't that many of us out there, at least compared to the Poles, who've written much more widely about their experiences as immigrants and children of immigrants. Also, Lithuanian-Americans of my parents' generation encouraged their children to go into practical fields such as engineering and nursing. Perhaps surprisingly – because there are fewer of them – Lithuanian-Canadians have led the literary way. Antanas Sileika's first novel, Buying on Time, is a wonderful and very funny book about growing up Lithuanian-Canadian. And Irene Guilford's The Embrace examines the complex relationships between Lithuanians in the homeland and the diaspora. Both authors have influenced my own writing.

|

|

ELLEN CASSEDY Ellen Cassedy traces her Jewish family roots to Rokiskis and Siauliai. Her new book, We Are Here: Memories of the Lithuanian Holocaust, was published in March and will appear in Lithuanian soon. She lives in Washington, D.C. Visit her website at www.ellencassedy.com.

|

|

|

DAIVA MARKELIS Born in 1957 in Chicago to Lithuanian immigrant parents and raised in Cicero, Daiva Markelis has found unexpected contentment amidst the cornfields of Central Illinois. She is an associate professor of English at Eastern Illinois University, where she teaches creative writing, composition and rhetoric, women’s memoir, and myth and culture. She is a cofounder of Past/Forward, a memoir-writing group open to the public that meets twice a month and consists of ordinary people, many of them retired, writing moving, insightful, often humorous life stories. |

|

Daiva received her doctorate from the University of Illinois at Chicago in Language, Literacy, and Rhetoric. Her dissertation deals with the literacy habits and oral traditions of Lithuanian immigrants; chapters have been published in the journals Written Communication and Lituanus, and in the edited volumes Ethnolinguistic Chicago and Letters across Borders: The Epistolary Practices of International Migrants. Daiva has presented her research at the Modern Language Association, the Conference on College Composition and Communication, the Association for the Advancement of Baltic Studies, and the National Council of Teachers of English. She has also written several academic papers in her native Lithuanian.

Her master’s degree is in English with a specialization in creative writing, also from the University of Illinois at Chicago. Daiva’s short stories have been published in Cream City Review and Other Voices. Her creative nonfiction has appeared in The Chicago Tribune Sunday Magazine, The Chicago Reader, Crab Orchard Review, Writing on the Edge, Women and Language, Mattoid, Agora, and Fourth River. Mongrel Tongue was a finalist in the 2007 Arts and Letters competition in creative nonfiction. The Lithuanian Dictionary of Depression was a runner-up in the 2009 American Literary Review creative nonfiction contest. The Review published the essay in its Spring 2010 issue.

Daiva cheers for the White Sox. She loves to knit, scrap-book, read, and listen to music, everything from Bach, Beethoven, and Brahms to bebop, bluegrass, Brel, the Band, and the Black Eyed Peas. Her favorite color is red, her spirit animal is a polar bear, her astrological sign is Capricorn. She wants a puppy for Christmas.

|

|

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - (0) Comment

By the end of the book, author Daiva Markelis discovers

Her own way to be both

Lithuanian and American.

Daiva Markelis interviewed by Ellen Cassedy

Daiva Markelis's memoir, White Field, Black Sheep: A Lithuanian-American Life (University of Chicago Press, 2010), tells the story of her growing up as the daughter of postwar Lithuanian immigrants in the 1960's and '70's near Chicago.

The book alternates between the story of Markelis's youth – especially her struggle for cultural identity – and a series of touching later scenes with her octogenarian mother.

We see Daiva and her sister begging for real American Halloween costumes and a plastic Christmas tree, while the parents insist on speaking Lithuanian and holding true to their traditions. The descriptions of Catholic school, Lithuanian scout camp, and the family resort owned by Valdas Adamkus (who later returned to Lithuania and became its president) are tart and funny.

Markelis reveals a culture as well as a personal history. She writes affectionately about the streets, the buildings, even the tackiest billboards of her home town - while, at the same time, not shrinking from frank portrayals of racial tension and alcohol abuse. The portraits of her parents are filled with a lovely tenderness, even as she pokes fun and reveals some of their failings.

This tale of seeking cultural identity within an immigrant community comes to an uplifting conclusion. By the end of the book, Markelis has discovered her own way to be both Lithuanian and American.

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

VilNews e-magazine is published in Vilnius, Lithuania. Editor-in-Chief: Mr. Aage Myhre. Inquires to the editors: editor@VilNews.com.

Code of Ethics: See Section 2 – about VilNews. VilNews is not responsible for content on external links/web pages.

HOW TO ADVERTISE IN VILNEWS.

All content is copyrighted © 2011. UAB ‘VilNews’.

Click on the buttons to open and read each of VilNews' 18 sub-sections

Click on the buttons to open and read each of VilNews' 18 sub-sections

.jpg)