THE VOICE OF INTERNATIONAL LITHUANIA

|

VilNews has its own Google archive! Type a word in the above search box to find any article.

You can also follow us on Facebook. We have two different pages. Click to open and join.

|

Author Archive

- Posted by - (0) Comment

By Jennifer Virškus

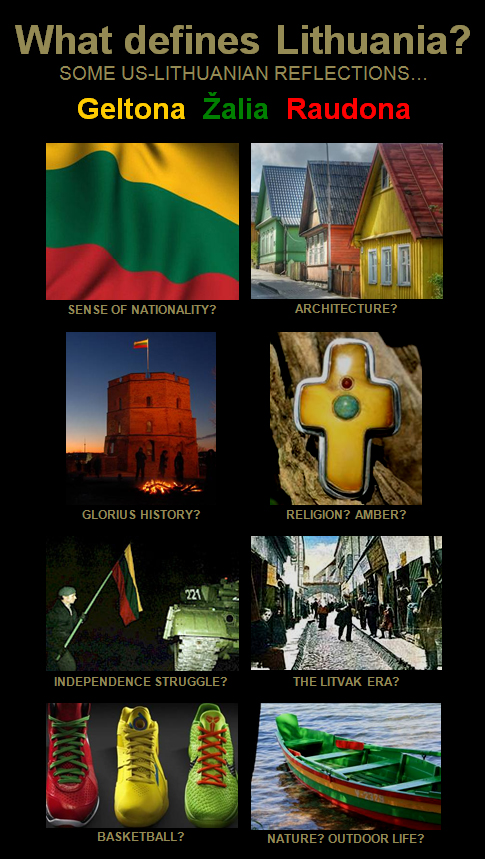

A nation can be defined by several different characteristics; geographical location, language, a common history, cultural body, or race. The Lithuanian nation is defined by all of these. Lithuania has a language which is unique in the world and a culture that runs deep. It shares more than two centuries of its history with Poland, and few other nations have survived occupation by so many different groups. There are several types of nationalism; primordial, civic, organic, and liberal. Because of the lack of opportunity in Lithuania, young Lithuanians have recently tried to convince themselves that they want to “forget” their Lithuanian culture and move on to a new life in the West, but it is not possible. Lithuanians will always be Lithuanians whether they are in Lietuva or not. This is evident in the Lithuanian-American community, though they are clearly Americans, their Lithuanian identity stays with them. This is because Lithuanian nationalism is both geographic and organic, an entity to which all Lithuanians belong, as parts of a whole and independently of their will, choice or consciousness.

| Jennifer Virškus Jennifer Virškus is a Lithuanian-American freelance writer, photographer, graphic designer, skier, sailor, traveler, and current MFA Writing student at California College of the Arts. While living in Vilnius, she founded the Kalnu Ereliai Ski Team. You can read more of her writing about skiing, sailing, and Lithuania at her blog, One Way Ticket. |

|

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - (3) Comment

By Jennifer Virškus

A nation can be defined by several different characteristics; geographical location, language, a common history, cultural body, or race. The Lithuanian nation is defined by all of these. Lithuania has a language which is unique in the world and a culture that runs deep. It shares more than two centuries of its history with Poland, and few other nations have survived occupation by so many different groups. There are several types of nationalism; primordial, civic, organic, and liberal. Because of the lack of opportunity in Lithuania, young Lithuanians have recently tried to convince themselves that they want to “forget” their Lithuanian culture and move on to a new life in the West, but it is not possible. Lithuanians will always be Lithuanians whether they are in Lietuva or not. This is evident in the Lithuanian-American community, though they are clearly Americans, their Lithuanian identity stays with them. This is because Lithuanian nationalism is both geographic and organic, an entity to which all Lithuanians belong, as parts of a whole and independently of their will, choice or consciousness.

To be clear, I must define what I mean by geographic and organic nationalism. Geographic nationalism is a combination of primordial and social construct nationalism. That is to say, it is based on an ethnic identity and linked to a territory (O'Laughlin). It is distinctive, based on a unique culture, religion, and literature. At the same time, geographic nationalism is constructed by the elites, though not necessarily for their own benefit. In the case of Lithuania, it was constructed and propagated out of a feeling of repression, and the desire of the people to live in a democratic state they could call their own. Johann Gottfried Herder used the term nationalism while applying it to Volk, emphasizing the organic nature of a people. This goes beyond the primordial definition to suggest that nationalism is something ingrained in a people. Herder says that the nation is a natural creation and nationalities are not the product of men, rather the “work of a living organic force that animates the universe.” National culture is, as Herder puts it, closed to foreign eyes (Viroli). So, Lithuanian nationalism is primordial in the sense that it is based on an ethnic identity, language, and culture; it is socially constructed, or rather promoted, by the elite who want to form a Lithuanian state, and organic in that birth is the only way for one to become Lithuanian.

The Lithuanian state was founded in the 13th century by Grand Duke Mindaugas. Lithuania began to expand in the 14th century, and by the beginning of the 15th century Lithuania was one of the largest countries in Europe

FIGURE 1: The map of Lithuania in the 13th-15th centuries.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Lithuanian_state_in_13-15th_centuries.png

In 1569 Lithuania and Poland formed the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, ruled by an elected king who was also Grand Duke of Lithuania. During the partitions of Poland, Lithuania was largely annexed by the Russian Empire, disappearing from the map completely (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2: Lithuanian borders from the 13th century to today.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:LithuaniaHistory.png

Germany occupied Lithuania during the First World War until the Lithuanians declared independence on 16 February 1918. The Lithuanian Republic was proclaimed later that year and enjoyed a brief period of independence between the two World Wars. Independence lasted barely 20 years as the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact of 1939 allowed the USSR to take control of Lithuania. The Lithuanian Soviet Socialist Republic was proclaimed on 21 July 1940. The Germans occupied Lithuania again from 1941-1944. The Red Army returned in 1944, deporting mass numbers of Lithuanians to Siberia. Small groups of anti-Soviet activists continued to resist until 1952, though, all political parties were disbanded and the country was ruled exclusively by the Lithuanian Communist Party. Gorbechev’s policy of glasnost during the 1980’s allowed Lithuanian nationalism—kept alive by underground and exile groups—to resurface in the reformist climate. Sajudis, the Lithuanian Movement for Reconstruction, was established in 1988. On 11 March 1990, Vytautas Landsbergis declared the independence of Lithuania from the Soviet Union. After a military intervention and a bloody attempt by the Soviets to reclaim the Vilnius TV Tower, the USSR council also recognized the independence of Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia. Today, Lithuania is a republic-parliamentary democracy, with Dalia Grybauskaitė serving as President and Head of State

FIGURE 3: Lithuania today.

To choose one event in which Lithuanian nationalism originated is impossible. Rather, it was the combination of so many centuries of repression which gradually built nationalism to its current strength. We can, however, establish the roots of Lithuanian nationalism, but to do so, we must first establish national identity by looking at Lithuania’s historical foundations that have lasting ethnic bonds and language, which in turn reflect self-identification. “Heroic” self-perceptions are shaped by the collective memory of the strength of the Grand Duchy (Kavolis 1991). Certainly, the fight for independence from Russia and then Germany during the First World War—and most recently, from the Soviet Union—play a major role. It is often the repression of a nation which becomes a rallying point for nationalism; this is certainly true in the case of Lithuania. Modern national identity is also encouraged by contemporary social and political changes. The opportunity to separate from the Soviet Union and the risk-taking courage of the Lithuanians has not only helped to transform Lithuania, but also re-enforced their own national identity. Lithuanians can take pride in the fact that their provincial struggle gained the attention of the world and paved the way for many other nations on the road to independence.

The role of language, religion, monuments, and music cannot be underestimated in determining the origin of nationalism in Lithuania. The Lithuanian language draws its roots from Sanskrit. It is historically and linguistically important since it retains most of its archaic Indo-European forms. This is due to the fact that during the Polish-Lithuanian dynasty, Polish was the preferred tongue, and during Russian occupation a policy of “russificaiton” insisted that Russian be used in daily life. Though the underground journal, Aušra (the Dawn), created by Jonas Basnavičius, brought the Lithuanian language en vogue among Lithuanian intellectuals, the language developed little until the first Lithuanian independence of 1918 when it could finally be spoken openly. The language quickly became a strong source of pride as more and more Lithuanians began to learn and speak the language. John Locke describes Lithuanian national identity as “national language and self-dedication.” In his autobiography, Lithuania Independent Again, former Lithuanian president, Vytautas Landsbergis, reflects on the lives of his grandfathers, Gabrielius Landsbergis and Jonas Jablonskis, who worked together on the staff of Vilniaus Žinios (The Vilnius News), the only legal publication in the Lithuanian language at the turn of the century. Gabrielius’ family had been polonized and he only began to learn Lithuanian after entering high school. As he embraced the language, he became “firm and enthusiastic in his belief that he was a Lithuanian” (Landsbergis 2000). The growing nationalist movement was solidified as the geographical region of Lithuania was defined by its language. Aušra is an instance in which the elite was attempting to construct Lithuanian nationalism to inspire a move toward independence, however in doing so, led many Lithuanians to discover and embrace their language and the ethnic identity that accompanied it, having a lasting effect on nationalism today.

In addition to inspiring the use of the Lithuanian language, Aušra, is also considered the organ of Catholic Nationalism (Welch). The Polish-Lithuanian Dynasty was surrounded by Lutheranism to the West and North, and Russian Orthodoxy to the East. Together with the language, the Catholic faith became something that set the Lithuanians apart from their neighbors. National independence was the long-term goal, but Aušra rejected revolutionary activity, concentrating on preserving a nationally conscious and morally strong people, which it said was a precondition for statehood. It proposed a state similar to Israel where citizenship is based on the primordial elements of Lithuanian nationality and the Catholic religion (Welch 1983). Catholicism became so intertwined with Lithuanian identity, that during the interwar years to be Lithuanian was to be Roman Catholic (Donskis 2002). Here we have an example of nationalism being tied to an element already ingrained in Lithuanian society. Lithuanians were already Catholic, what changed in the first part of the twentieth century is that suddenly being Catholic, and Lithuanian, was something to be proud of.

FIGURE 4: Kryžiu Kalnas (the Hill of Crosses), near Šiauliai.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Hill-of-crosses-siauliai.jpg

Many monuments in Lithuania that promote nationalism have been created out of ties to the Catholic church. Most notably, Kryžiu Kalnas (the Hill of Crosses), near Šiauliai. A Lithuania pilgrimage center, Kryžiu Kalnas is a small hill where many hundreds of thousands of crosses have been placed to represent Christian devotion and as a memorial to Lithuanian national identity. This monument dates to the 14th century and is an example of peaceful resistance to oppression. Soviet tanks tried to destroy it on three separate occasions, leveling the monument during the night and either burning the crosses or turning them into scrap metal. Each time, crosses reappeared within days. Today it is an international pilgrimage site of mystical proportions, home to hundreds of thousands of crosses.

One can also think of the Lithuanian flag (Figure 5) as a monument to the Lithuanians who fought and died for the freedom of their country. The flag, adopted on 19 April 1918, consists of three horizontal stripes of yellow, green and red, the three colors most used in traditional weaving. The yellow represents the fertile fields of Lithuania, golden with ripe rye, wheat and flax. The green is a symbol of the nation’s vitality, and the red is a monument to the blood shed in defending the freedom of the homeland (Blavasciunas). All the elements of Lithuanian nationalism are represented in the flag: the organic yellow and green of the life that continues to grow, social construct references to the blood shed—a rallying point which the elites can use to promote nationalism—and the primordial element of the traditional colors used.

FIGURE 5: The Lithuanian flag.

Like monuments, music plays an important role in the expression of Lithuanian nationalism, most importantly, the work of Mikalojus Konstantinas Čiurlionis. Čiurlionis worked at the end of the 19th century helping to spawn nationalism with his symphonic poems which speak of the beauty of Lietuva. His two most important works, Jūra (The Sea) and Miške (The Forest) describe the two most prominent features of Lithuanian geography. The sea was an important resource for Amber as well as being valuable for trade with Scandinavia and Western Europe. The forest was the setting of most of Lithuanian folklore and pagan traditions, which are still practiced today. Čiurlionis’s work is a musical illustration of ancient ritual, religious devotion and national nostalgia, tying Lithuanian national identity directly to the land.

The national anthem (Figure 6) written by Dr. Vincas Kudirka contains references not only to national themes, but also to “the paths of virtue” (Kavolis). Kudirka did not intend for his poem, “Tautos Hymnas” (“National Hymn”), which espoused a love for Lithuania, to become the national anthem (Blavasciunas), yet it also includes all the elements of the origin of Lithuanian nationalism already mentioned above. The first line, “Lietuva, tėvyne mūsų, tu didvyrių žeme!” (“Lithuania, my homeland, land of heroes!”) makes the geographical connection, while the rest of the poem goes on to glorify Lithuania’s history and virtue. It does not mention revolution; on the contrary, it speaks only of the moral good of the Lithuanian people who have “light and truth” guiding their steps. These are certainly primordial elements; they come straight out of historical Lithuanian culture and values. The anthem is organic as it refers to Lithuania’s “children” working for the good of their native land. This implies the land upon which they were born—going back to Herder's argument that national identity is correlated to one’s birthplace—is integral to their identity.

During the Soviet Occupation, attempts to unite the USSR meant not only “russificaiton” but the outright banning of everything Lithuania had to be proud of; the language, Catholicism, music—in particular folk music—and public celebration of national festivals. Many monuments were destroyed and churches were turned into science museums. Hélène Carrère d'Encausse asks the question in her book Decline of an Empire, “Has the Marxist ideology of human uniformity gained mastery over this diverse society in which for the first time in history it has taken root and come to power?” Soviet indoctrination had several effects. The older generation that had seen the capabilities of the Soviets were sufficiently scared to live quietly, not wanting to risk deportation. Small children were the easiest to indoctrinate, and many went on to join the Komsomol (Soviet Young Communist League). There was however a small group of students, particularly at the time of Stalin’s death, who were eager to rediscover the outside world and their own heritage. Vytautas Landsbergis belongs to this group, and he was fortunate enough to study under Jadvyga Čiurlionytė, sister to Čiurlionis. She had established, by her own efforts, a department of Lithuanian folk music at the Vilnius Conservatoire (Landsbergis 2000). Landsbergis went on to become an expert in the music of Čiurlionis, writing several books on his painting and music. Together with the work of Čiurlionis’s sister, Landsbergis was the founder of a revival in Lithuanian Nationalism in the 1950’s, inspiring his own generation, and generations to follow to the idea that Lithuania was something to be proud of, and worth defending.

Opposition to the Soviet regime in Lithuania stems mainly from national and religious sentiments (Welch); of course the two are directly related. As a response to the Soviet secularization of society, a religious movement was spawned based on the overtly religious society which existed before the occupation. Many who were categorized as “non-believers” during Soviet times were actually secret practitioners. Religion became a personally and privately expressed, rather than institutionally expressed, experience. The Catholic rights movement evolved to be a comprehensive campaign against secularization (Welch) which was aided by the visit of Pope John Paul II to Poland in 1979, a visit that deeply disturbed communist authorities across the Eastern Bloc. The Catholic church was in a better position to publicly promote a nationalist movement than a small group of individuals such as the one Landsbergis belonged to as the Soviets could not send the entire church to the Gulag. In her article, “Nationalism and Lithuanian Dissent”, Irene Welch discusses in depth the ethnographic clubs and underground publications such as Varpas (The Bell) and Laisvės Šauklys (The Herald of Freedom), which were part of the cultural movement that inspired attempts from underground political organizations such as the Lithuanian Revolutionary Liberation Front. These movements demanded a more aggressive opposition than the Catholic movement did. They were involved, like Landsbergis, in a rediscovery and preservation of the primordial elements of Lithuanian nationalism which had been attacked by the Communist Party and the KGB. Nationalism never died in Lithuania, but it is fair to say that it was difficult to express publicly.

A study was done in the early 1980's about the retention of nationalism in second generation Lithuanian-Americans/Canadians in Chicago and Montreal (Figure 7). It found that there was a significant retention of culture and nationalism among young adults in their twenties. In his article, Virga Jelionis wrote that in identity formation, an individual draws both from the collective and self-identity. Jelionis proves that Lithuanian-Americans/Canadians draw not from the collective identity of either America or Canada, but rather from their Lithuanian heritage, and their own self-identity is not American or Canadian, but Lithuanian. The study is interesting because in Chicago, there is an established and definite neighborhood where most Lithuanians live and socialize, no doubt contributing to their own retention of culture, however, in Montreal where we see the same cultural trends, no such neighborhood exists. This shows us that retention of Lithuanian nationalism is deeper, not simply constructed through daily exposure. It is something that a person is born with, and cannot escape. Not only do we see that Lithuanian-Americans/Canadians are proud and comfortable in their ethnic community, but they prefer to engage in social activities with other Lithuanians and are very interested and concerned in the future of their homeland. In addition, the study shows that second generation Lithuanians still feel strongly that their own children attend Saturday school[1] and speak Lithuanian at home. While Lithuanian nationalism is based on primordial elements, Saturday school, scout groups, and dance troupes are ways in which nationalism is socially constructed and promoted. What is interesting and important to note, is that Lithuanian nationalism, at least in expatriate communities, is being constructed by the masses, both individually and collectively, rather than an educated elite. Nearly 90% of respondents answered either “yes” or “sometimes” to the question, “I am very conscious of, or preoccupied with, my [Lithuanian] nationality.” Very simply, Lithuanian nationalism, and being Lithuanian is important.

Nationalism in Lithuania today, is a very open experience, though, participation in Catholic activities is significantly lower. Communism succeeded in wiping out religious identity in the current twenty-something generation. This was the last generation born under the Soviet regime, and the current widespread trend away from the church in Europe also contributes. In 1991, there was no organized culture, and there was some debate about the path Lithuania should follow; join the pluralistic West, reaffirm certitudes of Lithuania’s own past, or seek to create a more universal post-totalitarian culture (Kavolis). One trend concerns the belief that individuals begin as members of a nation and that its leaders are "indistinguishable" from the nation, as the Lithuanian Democratic Party declared about Vytautas Landsbergis (Kavolis). It would seem that Lithuania is leaning toward reaffirming “certitudes of Lithuania’s past;” we see nearly daily celebrations of “memorial days, numerous re-inaugurations of destroyed monuments, reburials of exhumed bodies of Siberian deportees—expressions of the ancient belief that a person ultimately belongs to his or her native soil” (Kavolis). Kryžiu Kalnas is covered with more crosses than ever, and new statues are being erected constantly in honor of Lithuania’s children, fallen in her defense. The brave men and women who stood up to the tanks of the Red Army during the attempted capture of the Vilnius TV tower were given Lithuania’s highest Medal of Honor. Shortly after independence was declared, an important statue of Lenin was taken down to be replaced with that of a famous Lithuanian personality, Frank Zappa. Lithuanians can finally be openly and publicly proud of whom they are, where they come from, and the language they speak.

I consider myself a Lithuanian nationalist, though my heritage is only half Lithuanian and my upbringing was much more American than ethnic Lithuanian. We ate kugėlis and babka on Christmas morning, had Easter eggs my Grandmother painstakingly decorated with beeswax and natural dyes every year, and went to a Lithuanian church once in a while. But I didn’t speak Lithuanian, or go to Saturday school, nor did I attend summer heritage camp at Dainava. My exposure to Lithuanian culture was more subtle—my Grandmother’s accent, a word here or there. Sometimes my Dėdė[2] Balys would ask my brothers and I for clothes or old toys to send to “the cousins” in Lithuania. I didn’t know what it meant to be Lithuanian, but I knew it was something I belonged to and something I was proud of. My first public exhibition of nationalism came when I was twelve. I bought a pin representing the American and Lithuanian flags flying together. This was in 1989, and there was a stir in the Lithuanian community that soon Lietuva would be independent again. My nationalism was not constructed—it was hardly encouraged—it is primordial, based on a culture I still know so little about, and it is organic, something I was born with, and something that will continue to grow with me. Today Lietuva is independent, and going there means going home.

Bibliography

Carrère d'Encausse, Hélène. Decline of an Empire. HarperCollins, 1981.

Dobryninas, Aleksandras. “The Paradoxes of Freedom in Search of their Roots and Fruits.” Lituanus 39 no.4, (1993).

Donskis, Leonidas. Identity and Freedom: Mapping nationalism and social criticism in twentieth-century Lithuania. London: Routledge, 2002.

Hartman, Gary. “The Origins and Growth of Baltic Nationalism as a Force for Independence.” Lituanus 38 no. 3 (1992).

Jelionis, Virga. “Ethnic Identification: A Study of Second-Generation Lithuanians’ Retention of Culture.” Lituanus 28 no. 3 (1982).

Kavolis, Vytautas. “The Second Lithuanian Revival: Culture as Performance.” Lituanus 37 no.2 (1991).

Landsbergis, Vytautas. Lithuania Independent Again: The Autobiography of Vytautas Landsbergis. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2000.

O'Laughlin, John. GEOG 4712 “Politcal Geography.” University of Colorado at Boulder, 2002.

Ramunas Personal Pages. http://www2.omnitel.net/ramunas/Lietuva/

Taylor, Peter J. and Colin Flint. Political Geography. Essex: Pearson Education Limited, 2000.

Valentiejus, Algis. “Early Lithuanian nationalism: sources of its legitimate meanings in an environment of shifting boundaries.” Nations and Nationalism 8 no. 3 (2002): 315–33.

Welch, Irene. “Nationalism and Lithuanian Dissent” Lituanus 29 no.1 (1983).

|

Jennifer Virškus

|

|

Figure 6

Lithuania, my homeland, land of heroes!

Let your Sons draw strength from the past.

Let your children follow only the paths of virtue,

working for the good of their native land and for all mankind.

Let the sun banish all darkness from Lithuania,

with light and truth always guiding our steps.

Let the love of Lithuania burn in our hearts

and for the sake of our country let unity blossom.

Figure 7

LITUANUS

LITHUANIAN QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES

Volume 28, No.3 - Fall 1982

Editor of this issue: Antanas Klimas

ISSN 0024-5089

Copyright © 1982 LITUANUS Foundation, Inc.

ETHNIC IDENTIFICATION:

A STUDY OF SECOND-GENERATION LITHUANIANS' RETENTION OF CULTURE

VIRGA JELIONIS

Hofstra University

1-Strongly Agree 5-Strongly Disagree

Having a recognized place in my ethnic community is important to me.

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

|

|

__________________________________________________________________________________ |

|

|||||

|

36% |

19% |

36% |

- |

- |

9% |

(C) |

|

54% |

36% |

9% |

- |

- |

- |

(M) |

I gain feelings of self-worth from the position I occupy in my ethnic community.

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

|

|

___________________________________________________________________________________ |

|

|||||

|

36% |

27% |

19% |

9% |

- |

9% |

(C) |

|

45% |

27% |

19% |

9% |

- |

- |

(M) |

I feel most satisfied when I am engaged in social activities with other Lithuanians.

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

|

|

___________________________________________________________________________________ |

|

|||||

|

36% |

45% |

9% |

- |

- |

9% |

(C) |

|

27% |

36% |

27% |

9% |

- |

- |

(M) |

I am interested in the future of the Lithuanian homeland.

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

|

|

__________________________________________________________________________________ |

|

|||||

|

63% |

9% |

19% |

- |

- |

9% |

(C) |

|

45% |

19% |

36% |

- |

- |

- |

(M) |

I feel most satisfied when I am engaged in activities within the Lithuanian community.

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

|

|

__________________________________________________________________________________ |

|

|||||

|

27% |

36% |

27% |

- |

- |

9% |

(C) |

|

27% |

36% |

19% |

1 9% |

- |

- |

(M) |

I feel it is important that Lithuanian-(Americans/Canadians) visit Lithuania at least once in their lifetime.

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

|

|

__________________________________________________________________________________ |

|

|||||

|

45% |

9% |

1 9% |

19% |

- |

9% |

(C) |

|

63% |

9% |

27% |

- |

- |

- |

(M) |

I feel most satisfied when I am in the circle of my Lithuanian friends.

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

|

|

__________________________________________________________________________________ |

|

|||||

|

36% |

19% |

36% |

9% |

- |

- |

(C) |

|

27% |

27% |

27% |

- |

19% |

- |

(M) |

I feel it is important that Lithuanian-(American/Canadian-an) children attend Saturday school.

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

|

|

________________________________________________________________________________ |

|

|||||

|

63% |

- |

19% |

- |

9% |

9% |

(C) |

|

63% |

19% |

19% |

- |

- |

- |

(M) |

I feel it is important that Lithuanian-(Americans/Canadians) respect their parents' wishes to speak Lithuanian in their parents' home.

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

|

|

________________________________________________________________________________ |

|

|||||

|

63% |

9% |

19% |

- |

- |

9% |

(C) |

|

36% |

45% |

9% |

- |

9% |

- |

(M) |

I would want my children to be raised in a Lithuanian environment (i.e. attend Lithuanian school, speak Lithuanian in the home, socialize with other Lithuanians, participate in Lithuanian organizations and clubs, etc.)

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

|

|

__________________________________________________________________________________ |

|

|||||

|

63% |

9% |

- |

9% |

9% |

9% |

(C) |

|

54% |

27% |

9% |

- |

9% |

- |

(M) |

It is important for Lithuanian-(Americans/Canadians) to stay together as a closely-knit group for the purpose of keeping the culture alive and growing outside the homeland.

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

|

|

__________________________________________________________________________________ |

|

|||||

|

54% |

19% |

27% |

- |

- |

- |

(C) |

|

54% |

36% |

- |

9% |

- |

- |

(M) |

Lithuanian-(Americans/Canadians) should speak Lithuanian amongst themselves.

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

|

|

__________________________________________________________________________________ |

|

|||||

|

9% |

45% |

19% |

9% |

9% |

9% |

(C) |

|

19% |

27% |

19% |

19% |

19% |

- |

(M) |

In order to keep the Lithuanian culture alive in North America Lithuanian-(Americans/Canadians) should participate as fully as possible in their own cultural community.

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

|

|

__________________________________________________________________________________ |

|

|||||

|

54% |

19% |

1 9% |

9% |

- |

- |

(C) |

|

27% |

54% |

- |

- |

19% |

- |

(M) |

It is important that other (Americans/Canadians) be made aware of the Lithuanians' fight for freedom for their homeland.

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

|

|

__________________________________________________________________________________ |

|

|||||

|

81% |

9% |

9% |

- |

- |

- |

(C) |

|

72% |

19% |

- |

9% |

- |

- |

(M) |

To be a Lithuanian-American/Canadian) means to carry responsibility to be politically active in the fight for Lithuania's freedom.

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

|

|

__________________________________________________________________________________ |

|

|||||

|

9% |

63% |

9% |

9% |

9% |

- |

(C) |

|

9% |

36% |

19% |

9% |

9% |

19% |

(M) |

I have a duty to educate others about the Lithuanian culture.

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

|

|

__________________________________________________________________________________ |

|

|||||

|

27% |

45% |

19% |

- |

9% |

- |

(C) |

|

19% |

19% |

63% |

- |

- |

- |

(M) |

Of those people whom you would call your friends what proportion are Lithuanian?

|

all of them |

nearly all of them |

more than half |

less than half |

none |

|

|

________________________________________________________________________________ |

|

||||

|

9% |

45% |

36% |

- |

9% |

(C) |

|

- |

45% |

9% |

45% |

- |

(M) |

I always celebrate Christmas Eve Supper (Lith. Kūčios) with my family.

|

Yes |

Sometimes |

No |

|

|

________________________________________________________ |

|

||

|

63% |

9% |

27% |

(C) |

|

100% |

- |

- |

(M) |

I always celebrate Lithuanian Independence Day (February 16th).

|

Yes |

Sometimes |

No |

|

|

_______________________________________________________________ |

|

||

|

36% |

27% |

36% |

(C) |

|

81% |

19% |

- |

(M) |

I celebrate February 16th by attending a Lithuanian function.

|

Yes |

Sometimes |

No |

|

|

_______________________________________________________________ |

|

||

|

54% |

19% |

27% |

(C) |

|

81% |

19% |

- |

(M) |

I always celebrate Easter with my family.

|

Yes |

Sometimes |

No |

|

|

_______________________________________________________________ |

|

||

|

45% |

27% |

27% |

(C) |

|

91% |

9% |

- |

(M) |

I attend Mass at a Lithuanian church only as an obligation I am fulfilling for my parents.

|

Yes |

Sometimes |

No |

|

|

_______________________________________________________________Ž |

|

||

|

19% |

19% |

63% |

(C) |

|

-% |

45% |

54% |

(M) |

Lithuanians should make themselves known by their Lithuanian names in all of their non-Lithuanian environments.

|

Yes |

Sometimes |

No |

|

|

________________________________________________________________ |

|

||

|

72% |

9% |

19% |

(C) |

|

81% |

9% |

9% |

(M) |

I believe the family is important in keeping our culture alive.

|

Yes |

No |

|

|

___________________________________________ |

|

|

|

91% |

9% |

(C) |

|

81% |

19% |

(M) |

I am very conscious of, or preoccupied with, my nationality.

|

Yes |

Sometimes |

No |

|

|

_________________________________________________ |

|

||

|

54 |

27 |

19% |

(C) |

|

45 |

54 |

- |

(M) |

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - (0) Comment

![]() Summer is here!

Summer is here!

30C(86F) in Vilnius!

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

![]()

More and more Belarusians

come to visit Lithuania by car

The Lithuanian Border Agency blamed a sharp increase in travelers for the long queues at the Belarusian-Lithuanian border checkpoints, BelTA has learnt.

Last weekend the Belarus-Lithuania border saw long queues of motors cars and trucks at Kamenny Log-Medininkai and Kotlovka-Lavoriskes, with travelers waiting for five hours at the neutral border-crossing territory after passing through the customs and border control at the Belarusian side.

According to head of the PR department of the Lithuanian Border Agency Giedrius Misutic, queues were formed at all main checkpoints of the Belarusian-Lithuanian border due to a skyrocketed number of travelers to Lithuania. “The situation at the weekend was unstable. There were long queues at the entry to Lithuania, and the reason for this is a huge number of travelers. For example, on Saturday the border checkpoint Benyakoni-Salcininkai accommodated nearly 300 trucks at a time when its rated capacity is only 200. The checkpoint is designed to handle 900 motor cars a day. On 28 April it accommodated 1000 either side. The same situation was at the Lavoriskes-Kotlovka,” the Lithuanian official said.

In his words, besides the main reason for an increased flow of motor cars at the weekend, there were also other reasons. Poland has recently lowered the number of heavy haulers (over 12 tonnes) able to cross its border. Apart from that this country reduced the amount of fuel allowed for being carried across the border in fuel tanks. Therefore many large goods vehicles have been forced to go to Poland via the Belarusian-Lithuanian border.

The Lithuanian side acknowledges that there has been a temporary failure in the operation of check systems for third-country visas, which also contributed to lengthy delays at the border.

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - (0) Comment

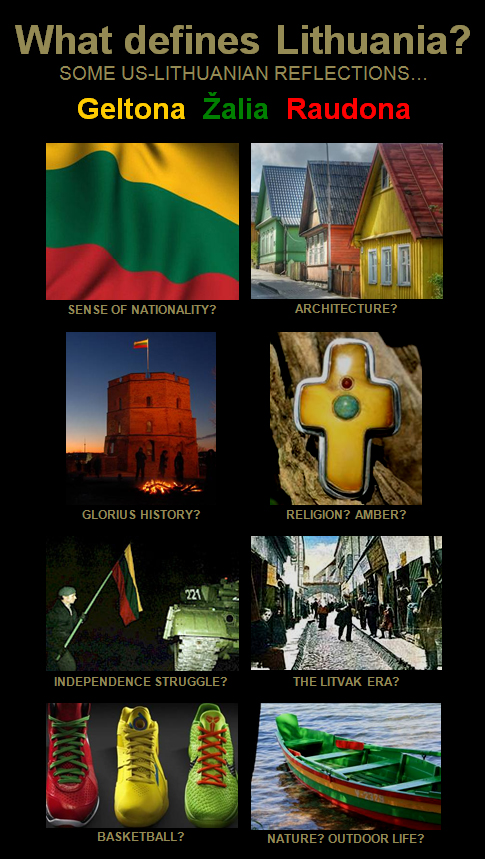

Rūta Šepetys and Ellen Cassedy

Probably our relatives brushed shoulders in the marketplace

Rūta Šepetys and Ellen Cassedy interviewed by Jennifer Virškus

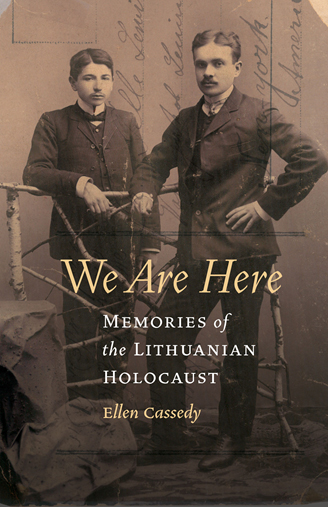

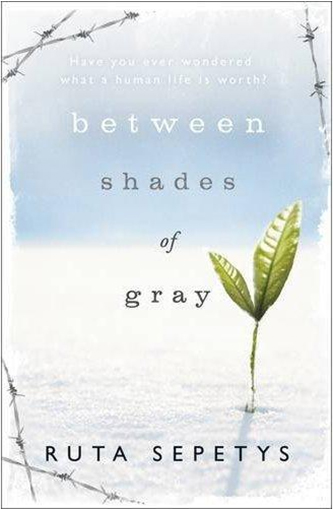

Two new books making a splash in the literary world—Between Shades of Grey by Rūta Šepetys and We Are Here: Memories of the Lithuanian Holocaust by Ellen Cassedy—take place in WWII Lithuania. Though the two women's stories begin in much the same place—Sepetys's grandfather is from a village near Biržai, while Cassedy's great-grandfather hails from Rokiškis only 60km away—the books, and their stories, couldn't be more different. We Are Here is a first person memoir about Cassedy's journey to discover her Litvak heritage while studying Yiddish at Vilnius University. Between Shades of Grey is a young adult fiction novel about a 15-year-old girl who is deported to Siberia along with her mother and younger brother.

Individually, the books have met with incredible success. Between Shades of Grey, which came out in paperback this month in the US, has been translated into twenty-five languages and sold in thirty countries. Only in bookstores for a little over a month, We Are Here is racking up rave reviews at home and abroad. When speaking of the book, which will be released in Lithuania in May, former president Valdas Adamkus said, “This eloquent book can help us to reach out, open our hearts, and rediscover one another in a spirit of mutual understanding.”

Indeed, the need for understanding is a theme in both books, and together, they provide a more complete portrait of a time in history when Lithuania's identity was at its most complex—not only for their readers, but for the authors, too. “I went to Lithuania, hoping to decide who was right and who was wrong; to put people in a column, who was a victim, who was a killer. And then those lines began to blur,” says Cassedy.

Šepetys went one step further, “The intersection that I've experienced [between the ethnic Lithuanian fear of the Soviets and the Litvak fear of the Nazis] is one of regret … People that I've spoken to say that some of their greatest regrets weren't the things that they forgot to pack with them; they were human interactions with people. Something that was said or done, a suspicion or paranoia; but they also explained that those are the casualties of war.”

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - (2) Comment

Rūta Šepetys and Ellen Cassedy

Probably our relatives brushed shoulders in the marketplace

Rūta Šepetys and Ellen Cassedy interviewed by Jennifer Virškus

Two new books making a splash in the literary world—Between Shades of Grey by Rūta Šepetys and We Are Here: Memories of the Lithuanian Holocaust by Ellen Cassedy—take place in WWII Lithuania. Though the two women's stories begin in much the same place—Sepetys's grandfather is from a village near Biržai, while Cassedy's great-grandfather hails from Rokiškis only 60km away—the books, and their stories, couldn't be more different. We Are Here is a first person memoir about Cassedy's journey to discover her Litvak heritage while studying Yiddish at Vilnius University. Between Shades of Grey is a young adult fiction novel about a 15-year-old girl who is deported to Siberia along with her mother and younger brother.

Individually, the books have met with incredible success. Between Shades of Grey, which came out in paperback this month in the US, has been translated into twenty-five languages and sold in thirty countries. Only in bookstores for a little over a month, We Are Here is racking up rave reviews at home and abroad. When speaking of the book, which will be released in Lithuania in May, former president Valdas Adamkus said, “This eloquent book can help us to reach out, open our hearts, and rediscover one another in a spirit of mutual understanding.”

Indeed, the need for understanding is a theme in both books, and together, they provide a more complete portrait of a time in history when Lithuania's identity was at its most complex—not only for their readers, but for the authors, too. “I went to Lithuania, hoping to decide who was right and who was wrong; to put people in a column, who was a victim, who was a killer. And then those lines began to blur,” says Cassedy.

Šepetys went one step further, “The intersection that I've experienced [between the ethnic Lithuanian fear of the Soviets and the Litvak fear of the Nazis] is one of regret … People that I've spoken to say that some of their greatest regrets weren't the things that they forgot to pack with them; they were human interactions with people. Something that was said or done, a suspicion or paranoia; but they also explained that those are the casualties of war.”

- Ellen Cassedy

“The intersection that I've experienced [between the ethnic Lithuanian fear of the Soviets and the Litvak fear of the Nazis] is one of regret … People that I've spoken to say that some of their greatest regrets weren't the things that they forgot to pack with them; they were human interactions with people. Something that was said or done, a suspicion or paranoia; but they also explained that those are the casualties of war.”

- Rūta Šepetys

Neither of the women's upbringing had been particularly “Lithuanian”—or, in Cassedy's case, particularly Jewish. They were raised in mixed-heritage American homes, sprinkled with ethnic flavor. Cassedy's mother used Yiddish words in her daily speech, “We'd be in the kitchen and she would say, 'Hand me that shissel,' meaning that bowl;” but her name comes from her Irish-protestant father. Šepetys spent her childhood explaining her name to the people around her, “Everyone sees Rūta Šepetys and they're asking, and I'm constantly responding, I'm Lithuanian.” But while her grandfather was very connected to the Lithuanian community and they had all the traditional foods and holidays, she herself had no exposure to it outside her home.

Though they did not know each other, both women took their first trip to Lithuania around the same time—in the early 2000's. Šepetys was on a trip with her brother to find out more about her father's youth, “I was meeting cousins … [My father] was in a DP camp for 9 years, so there are no photographs. I asked if they had any photos … and they told me that they had burned them all because they couldn't let anyone know that they were related.” Her grandfather was an officer in the Lithuanian army; when he fled, the rest of his family was put on the Soviet deportation list, just by association. “[My cousins] told me that some of my grandfather's extended family had been deported—I had no idea that the deportations had affected our family. And then to find out that … the freedom that I have as an American perhaps came at the expense of someone else.” She says that the character of Joana in her book represents her father's journey of fleeing Lithuania, going into the DP camp. “I think how much I take for granted on a daily basis, and when I learned that, I thought, 'Oh my gosh!' I was so ignorant. I was almost ashamed that I had no idea that this part of history had affected my family.” That was when she decided she had to tell the story.

A loyalty to Lithuania itself wasn't a part of Cassedy's upbringing. “Where exactly is Lithuania? That wasn't really how I thought about it. I thought of Eastern Europe as a whole, and where was the exact spot, I didn't know.” Her mother had passed away, and she had begun to feel she had lost contact with that part of her heritage. She wanted to study Yiddish in the region where her grandfather was from and decided to enroll at the Vilnius Yiddish Institute—though she did not have the overwhelming support of her peers. “People would say to me, 'There's no point going there, there's nothing there.' That's a very common attitude for Jews in my generation to say.” But she didn't believe that.

“I began this journey in a rather one-dimensional way. I wanted to go to Lithuania and connect to my past, only my past, I wasn't seeing outside of the Jewish past. And then I got knocked over by these two surprises.” Just before Cassedy left for Lithuania the first time, her uncle revealed a secret to her about his activities during the Holocaust while living in the ghetto in Šiauliai. When she got to Rokiškis, she was told that there was an elderly man who wanted to speak to her about the things he had witnessed during the war. “Those two things really threw everything up in the air for me and launched me on this really life-changing journey, that really changed how I thought about Lithuania, how I thought about my family, thought about all people; so it really pushed me into a very different place.”

For both women, the experience of writing their books connected them to Lithuania in a way they had not imagined before. “As I started writing this book and getting involved in this project of looking at how Lithuania has been engaging with its 20th century past and with the Holocaust … I went there and started meeting people … and that has made me feel more connected and made me feel like, 'Well yes, I am Lithuanian,'” explained Cassedy.

“My family history—definitely surprising—was that my father was not familiar with what had happened to his family until 1991 when he went back.” She says even then they didn't share the full details with him; their freedom was still fragile. “You didn't talk about what happened in Siberia.”

Both Cassedy and Šepetys express a desire to start a conversation about the events of WWII. “I think that what Ellen is doing is so important, because it's a wound, a wound on Lithuania. And it will continue to bleed until we can clot it somehow,” says Šepetys. “We're third parties, Ellen and I. We didn't loose family members (Editors note: Ellen actually did.), and I understand there's a lot of deep-seeded anger and resentment, but I hope that we can create a dialogue.” Though, she stresses that the crimes of Stalin and Hitler cannot be lumped together.

What became clear to Cassedy was a sense of competing martyrdom; every group wanted to be able to say, No WE suffered the most. “It's not about who suffered the most; everybody needs to be heard.” She believes that we have to remember the past, but to listen and acknowledge each other in order to make a common cause. “We can't just sit in our corners and hate each other generation after generation.”

“Jewish and ethnic Lithuanian cultures lived side by side for many years and absorbed something from each other,” says Cassedy. “What I would like to see is a proud Lithuania, but one that is open to a multiculturalism.” Šepetys echoes that sentiment, “Lithuania is a small country, but it can teach the world large lessons of peaceful endurance, and the miraculous nature of the human spirit.” She says that even though Lithuania is defined by its past, it must look toward the future.

Šepetys studied at Hillsdale college with Dr. Aleksandras Štromas, a prominent Jewish-Lithuanian political scientist and dissident. “He said it's hard to dissect the situation because there is so much overlapping, it's not clear-cut. You can't just point a finger.” Her goal in writing her book was to give people the opportunity to learn about something they might not otherwise learn about. Recently, she was in a school to give a talk and a student said to her, “I knew you were coming, and I looked up Lithuania last night, and you have some really great basketball players!” Šepetys adds, “I'm so happy that people look it up, and know where it is on a map.”

“I do feel a real connection to the people who are going to shape the future of Lithuania, and I feel myself to be one of those people, in a way that I didn't,” explains Cassedy. “It's not my country really. But I'm a sympathetic and interested observer.”

Šepetys says she has a sense of gratitude and patriotism to Lithuania. “I feel so proud to be Lithuanian, I have so much respect for [them], as I've said these people are so patriotic, selfless, generous, courageous, and I aspire—they're like superheroes to me. I'm so proud to be able to carry a Lithuanian name.” About her role as a Lithuanian-American author she says, “I would really hope that Lithuanian-Americans first and foremost help with a very simple thing, which is an awareness of Lithuania.”

Cassedy is hopeful that Lithuania is opening up to a part of its history, which is not only the friction of different peoples living there, but also the possibility that they can enjoy their differences and appreciate each other. I asked her if she knew that her great-grandfather and Šepetys's grandfather hailed from the same region, “I didn't know that!” She laughs, “You know, it's probably like, our relatives brushed shoulders in the marketplace.”

We Are Here is a first person memoir about Cassedy's journey to discover her Litvak heritage while studying Yiddish at Vilnius University. |

Between Shades of Grey is a young adult fiction novel about a 15-year-old girl who is deported to Siberia along with her mother and younger brother. |

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - (1) Comment

“Why do you love

Jews so much?”

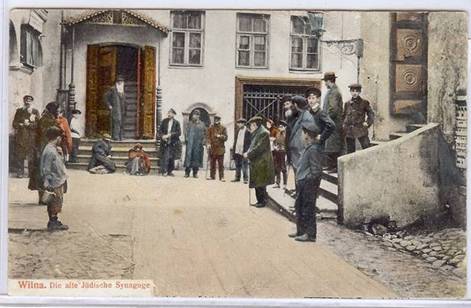

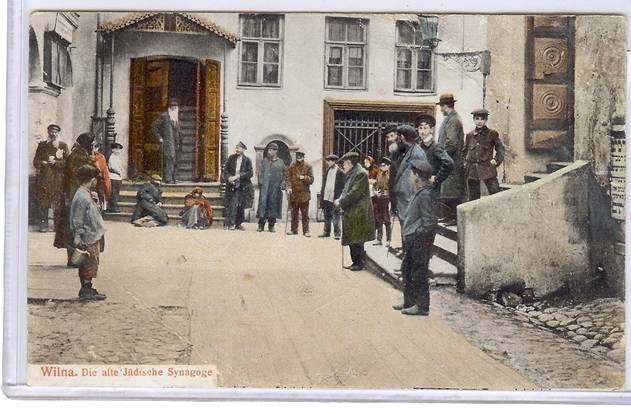

Vilnius, the old Jewish Synagogue.

By Aage Myhre, Editor-in-Chief

aage.myhre@VilNews.com

I have repeatedly been asked, by Lithuanians and others why VilNews, and I as a Norwegian without a single drop of Jewish blood, love Jews so much? Recently I met a Lithuanian-American, well educated and well read, who yet bombastically trumpeted. "You lick the asses of the Jews, Aage."

During my meetings with Jews in South Africa, where 90% of the Jewish population of almost 100 000 are of Lithuanian descent, I have also been asked why I have such great interest in Litvaks.

My answer to all these, has been that I do not love Jews more than other peoples.

But I also tend to add that I am always impressed by people who achieve more than the common herd. Intelligence and wisdom are to me among the most important qualities a person can have, and I have no problem admitting that these are qualities I've seen a lot of among the Jews I have known through life.

As to the Litvaks, they were subjected to an almost total extinction here in Lithuania during the Holocaust. It was an assault and a genocide of an unimaginable scale that we must never forget, and which memory must find its fair balance in the mental as well as in the practical.

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

“Why do you love Jews so much?”

- Posted by - (14) Comment

Vilnius, the old Jewish Synagogue.

By Aage Myhre, Editor-in-Chief

aage.myhre@VilNews.com

I have repeatedly been asked, by Lithuanians and others why VilNews, and I as a Norwegian without a single drop of Jewish blood, love Jews so much? Recently I met a Lithuanian-American, well educated and well read, who yet bombastically trumpeted. "You lick the asses of the Jews, Aage."

During my meetings with Jews in South Africa, where 90% of the Jewish population of almost 100 000 are of Lithuanian descent, I have also been asked why I have such great interest in Litvaks.

My answer to all these, has been that I do not love Jews more than other peoples.

But I also tend to add that I am always impressed by people who achieve more than the common herd. Intelligence and wisdom are to me among the most important qualities a person can have, and I have no problem admitting that these are qualities I've seen a lot of among the Jews I have known through life.

As to the Litvaks, they were subjected to an almost total extinction here in Lithuania during the Holocaust. It was an assault and a genocide of an unimaginable scale that we must never forget, and which memory must find its fair balance in the mental as well as in the practical.

On 4 April, the United States and many other countries welcomed the decision of the Government of Lithuania to appoint a fund for Jewish property compensation, calling it an important historical step toward justice.

“This law is an important step towards the restoration of historical justice and reconciliation. We welcome these and other Lithuanian Government’s steps evaluating the legacy of the Holocaust”, the U.S. ambassador to Lithuania, Anne E. Derse, said in a statement.

The Cabinet of Minister’s decision was also praised by the special U.S. envoy on issues of anti-Semitism, Hannah Rosenthal, who said that the United States supports Lithuania’s efforts to “evaluate the complex history of the period, and the commitment to fully implement the legal framework on compensation.”

I agree with both ladies. This was a step in the right direction in terms of the relationship between the Lithuanian Jews, and what once was their beloved homeland.

Then there are Litvaks who seem to blame Lithuania and Lithuanians for everything that happened here during the Holocaust. In the Baltimore Sun this week, as an example, Olga Zabludoff writes that “Lithuania tries to whitewash its role in the Holocaust.” This in response to the Lithuanian government’s decision to establish the mentioned fund.

Usually I tend to have great respect for Olga Zabludoff’s opinions, but in this case, she goes too far. There must be limits to how much one should scorn and distrust a country and its leaders for everything they do.

Fortunately, there are also many moderate Litvaks. Ellen Cassedy in Washington and Irena Veisaite here in Vilnius are good models in this respect. Feel free to read my interview with Dr. Veisaite, here https://vilnews.com/?p=2595

The problem I see is that there is still a considerable gap between Litvaks and many of today's ethnic Lithuanians, as I have described above. It seems that many on both sides do not want peace and reconciliation. They do not like each other, simply, and seems to be more interested in finding errors than points of light. Such behaviours do not build bridges or enhance reconciliation. Perhaps it’s now time for both sides to become more friendly and forgiving towards each other?

Unfortunately, Lithuania is today a poor country, and to pay $ 50M is a tremendous burden on a people who are struggling more than most in Europe, but fortunately this is balanced to a very large extent by the huge, annual support

payments from the EU, Switzerland and Norway.

Germany still pays, even today, more than 60 years after WWII, in an exemplary manner for the Nazi atrocities against Lithuania and the Jewish population here. Unfortunately, there is no sign that Russia will ever do the same, for the colossal atrocities they committed against Lithuanians during and after the war. Those who lost loved ones in Siberia or in the huge bloody guerrilla warfare that went on here for 10 years after the war, will never get any compensation, I'm afraid.

My first encounter with a Jew, in the spring of 1959, took place far north in Norway

The small farm I grew up on is located on the island Senja, far north in Norway. It was by far the smallest in my native village. But my father had always collected books. Lots of books. Good books. So our little house had shelves with books from cellar to attic. And I had early thrown myself into the reading of them all, so even though we were poor materially, I felt that we were rich in many other ways.

My first trip out from the island occurred in 1959, when I was six years old, and my father and I went to the nearest small town, Harstad, with the local boat an early spring morning. What an experience! We did our first stroll around in the town so my father could do his errands. Then he took me to a cafe. What a fantastic experience! Meatballs and mushy peas as main course and blueberry porridge with cream for dessert!

In the afternoon we came to a green house in the middle of the town. "Men Outfits" was written on a large sign above the entrance door to the shop which formed the ground floor. But it was not there my father steered us. He took me up a small outdoor concrete staircase to a door on the side of the green building. There, he pressed a button.

I had obviously never seen or used a bell, so in my curious enthusiasm, I did as my father had done: - I pressed the button next to the door so fast that my father did not manage to stop me in time. He took my hand brusquely away from the call button. Then we heard steps. Heavy steps coming slowly down the internal stairs, a staircase we still could not see.

The door opened, and two good friends embraced each other. My strict Christian father and Polish-Jewish Meyer Sokolsky very much enjoyed the reunion and meeting there at the doorway to this green house in the middle of Harstad.

It smelled smoke all the way down to the entrance. The room we soon come up to was heavily fogged by smoke from pipe and cigarettes.

But what a dream of a room! Filled with books from floor to ceiling. Books on tables and chairs. Books everywhere.

I thought I had come to paradise. My first encounter with a Jew had become a reality...

The farm I grew up on is located on the island Senja, far north in Norway. It was by far the smallest in my native village.

But my father had always collected books. Lots of books. Good books. So our little house had shelves with books

from cellar to attic. And I had early thrown myself into the reading of them all, so even though we were poor

materially, I felt that we were rich in many other ways.

Photo, by Hugo Løhre, of my tiny home village, Olaheim.

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - (0) Comment

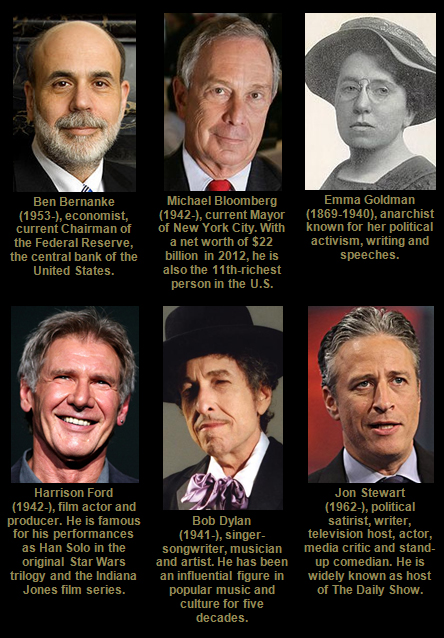

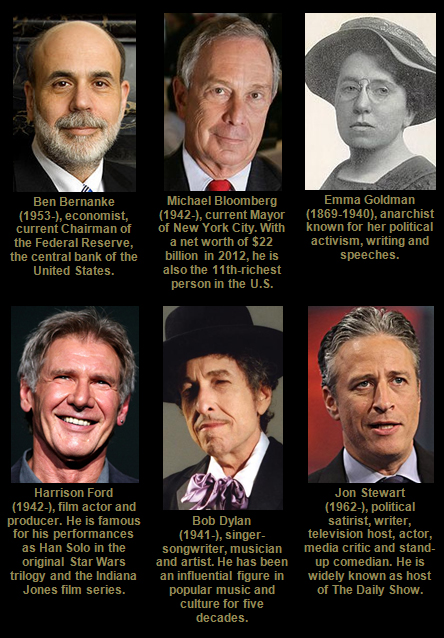

US-Lithuanian Jews

play many key roles

There are very strong communities of Jews of Lithuanian descent (Litvaks) around the world, especially in Israel, the United States, South Africa, Zimbabwe, Brazil and Australia.

In all these countries they hold top positions in politics, economy, science, culture and society in general.

Their names are frequently found among the Nobel laureates and in many other honorable contexts.

They often lead in matters and innovations that affect and influence us all, wherever in the world we live.

So also in the U.S., where they have been prominent leaders in economics, science and culture since the 1800s. It is, for example, said that Hollywood would not have existed had it not been for the Litvaks.

Litvaks are Jews with roots in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania: (present-day Lithuania, Belarus, Ukraine, and the northeastern Suwałki region of Poland).

Lithuania was historically home to a large and influential Jewish community that was almost entirely eliminated during the Holocaust. Before World War II there were over 110 synagogues and 10 yeshivas in Vilnius alone. Before World War II, the Lithuanian Jewish population was some 160,000, about 7% of the total population. Vilnius (then Wilno in the Second Polish Republic) had a Jewish community of nearly 100,000, about 45% of the city's total.

The reason for the Litvaks’ huge success is likely to be found in the fact that Vilnius through many centuries was considered the Jewish intellectual and cultural capital, with a huge number of teachers and scholars who taught and ruled this tiny community with wisdom and deep knowledge about a large number of disciplines.

Tolerance and interpersonal respect was also a hallmark of this community and for the whole of Lithuania through hundreds of years.

It was this that made Napoleon to name Vilnius as "Jerusalem of the North" when he came here on his way to Moscow in 1812. It is said that Napoleon himself became very surprised on what met him in Vilnius, a city so far away from the European mainstreams and still with a lively Mediterranean mood and life.

Vilnius was the first and only "Jewish city" Napoleon would ever see. He was no doubt aware of the Crusades, Inquisitions, pogroms and laws designed to discourage Judaic life. But here he had found a city, right before his eyes, that was an amazing exception to the rule.

And true enough, the history of the Litvaks is unusual and surprising. It was a history of mostly peaceful coexistence with other peoples and cultures that lasted for more than six centuries. It was a history that spawned an incredible number of eminent Jews, not the least of whom was Elijah ben Solomon Zalman (1720-1797), also known as “The Gaon of Vilnius”.

The "Golden Age of Jewry" in Lithuania started with Grand Duke Gediminas (1275-1341), the empire builder who took a liking to foreigners and Jews whose skills and education were badly needed in medieval Lithuania. In the early 1300's he attracted them to his realm with numerous perks, including guarantees of religious freedom and tax exemptions.

The Jews of Europe responded in droves, and Vilnius became the heralded centre of Jewish culture and learning. There would be synagogues, schools, theatres, publishing houses and the Yiddish Institute of Higher Learning. At a time when others in Europe were effectively illiterate, all the Jews in Vilnius could read and write.

This was so unusual that it provoked the invention of a brand-new word, "Vilner," meaning "an educated man with knowledge." For almost 700 years, the Litvaks became an inseparable part of Lithuanian society, having enriched the country’s economy, culture, science, and education.

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - (0) Comment

US-Lithuanian Jews

play many key roles

There are very strong communities of Jews of Lithuanian descent (Litvaks) around the world, especially in Israel, the United States, South Africa, Zimbabwe, Brazil and Australia.

In all these countries they hold top positions in politics, economy, science, culture and society in general.

Their names are frequently found among the Nobel laureates and in many other honorable contexts.

They often lead in matters and innovations that affect and influence us all, wherever in the world we live.

So also in the U.S., where they have been prominent leaders in economics, science and culture since the 1800s. It is, for example, said that Hollywood would not have existed had it not been for the Litvaks.

Litvaks are Jews with roots in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania: (present-day Lithuania, Belarus, Ukraine, and the northeastern Suwałki region of Poland).

Lithuania was historically home to a large and influential Jewish community that was almost entirely eliminated during the Holocaust. Before World War II there were over 110 synagogues and 10 yeshivas in Vilnius alone. Before World War II, the Lithuanian Jewish population was some 160,000, about 7% of the total population. Vilnius (then Wilno in the Second Polish Republic) had a Jewish community of nearly 100,000, about 45% of the city's total.

The reason for the Litvaks’ huge success is likely to be found in the fact that Vilnius through many centuries was considered the Jewish intellectual and cultural capital, with a huge number of teachers and scholars who taught and ruled this tiny community with wisdom and deep knowledge about a large number of disciplines.

Tolerance and interpersonal respect was also a hallmark of this community and for the whole of Lithuania through hundreds of years.

It was this that made Napoleon to name Vilnius as "Jerusalem of the North" when he came here on his way to Moscow in 1812. It is said that Napoleon himself became very surprised on what met him in Vilnius, a city so far away from the European mainstreams and still with a lively Mediterranean mood and life.

Vilnius was the first and only "Jewish city" Napoleon would ever see. He was no doubt aware of the Crusades, Inquisitions, pogroms and laws designed to discourage Judaic life. But here he had found a city, right before his eyes, that was an amazing exception to the rule.

And true enough, the history of the Litvaks is unusual and surprising. It was a history of mostly peaceful coexistence with other peoples and cultures that lasted for more than six centuries. It was a history that spawned an incredible number of eminent Jews, not the least of whom was Elijah ben Solomon Zalman (1720-1797), also known as “The Gaon of Vilnius”.

The "Golden Age of Jewry" in Lithuania started with Grand Duke Gediminas (1275-1341), the empire builder who took a liking to foreigners and Jews whose skills and education were badly needed in medieval Lithuania. In the early 1300's he attracted them to his realm with numerous perks, including guarantees of religious freedom and tax exemptions.

The Jews of Europe responded in droves, and Vilnius became the heralded centre of Jewish culture and learning. There would be synagogues, schools, theatres, publishing houses and the Yiddish Institute of Higher Learning. At a time when others in Europe were effectively illiterate, all the Jews in Vilnius could read and write.

This was so unusual that it provoked the invention of a brand-new word, "Vilner," meaning "an educated man with knowledge." For almost 700 years, the Litvaks became an inseparable part of Lithuanian society, having enriched the country’s economy, culture, science, and education.

To read more, go to our SECTION 12

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - (0) Comment

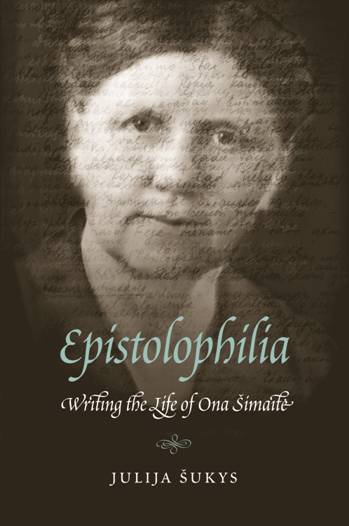

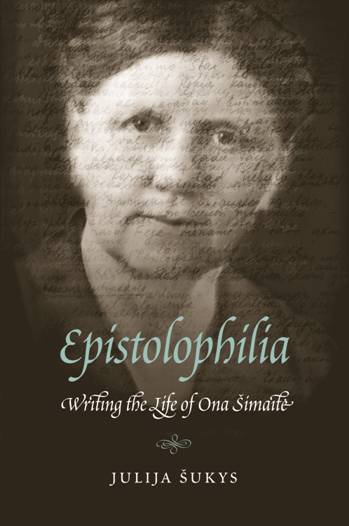

Ona Šimaitė:

Righteous – and Human

Julija Šukys,

Author of Epistolophilia: Writing the Life of Ona Šimaitė

Julija Šukys interviewed by Ellen Cassedy

In her new book, Epistolophilia, Julija Šukys follows the letters and journals—the “life-writing”—of Ona Šimaitė (1894–1970), a Lithuanian librarian who again and again slipped into the Jewish ghetto of German-occupied Vilnius carrying food, clothes, medicine, money, and counterfeit documents. Often she left with letters to deliver, manuscripts to hide, and even sedated children swathed in sacks. In 1944 she was captured by the Gestapo, tortured for twelve days, and deported to Dachau.

Šukys beckons back to life this quiet and worldly heroine. Ona Šimaitė is a giant of Holocaust history – one of the “Righteous among the Nations” honored at the Yad Vashem memorial in Israel – and yet little known.

Julija Šukys lives in Montreal, Canada. In addition to Epistolophilia, she is also the author of Silence Is Death; The Life and Work of Tahar Djaout. Visit her website at http://julijasukys.com.

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - (2) Comment

Ona Šimaitė:

Righteous – and Human

Julija Šukys,

Author of Epistolophilia: Writing the Life of Ona Šimaitė

Julija Šukys interviewed by Ellen Cassedy

In her new book, Epistolophilia, Julija Šukys follows the letters and journals—the “life-writing”—of Ona Šimaitė (1894–1970), a Lithuanian librarian who again and again slipped into the Jewish ghetto of German-occupied Vilnius carrying food, clothes, medicine, money, and counterfeit documents. Often she left with letters to deliver, manuscripts to hide, and even sedated children swathed in sacks. In 1944 she was captured by the Gestapo, tortured for twelve days, and deported to Dachau.

Šukys beckons back to life this quiet and worldly heroine. Ona Šimaitė is a giant of Holocaust history – one of the “Righteous among the Nations” honored at the Yad Vashem memorial in Israel – and yet little known.

Julija Šukys lives in Montreal, Canada. In addition to Epistolophilia, she is also the author of Silence Is Death; The Life and Work of Tahar Djaout. Visit her website at http://julijasukys.com.

What led Šimaitė to become a rescuer?

This is perhaps one of the most difficult questions to answer. What leads some people to behave in one way, and others differently? Where do such convictions and courage come from?

Šimaitė rarely addressed the question of why she did what she did, perhaps because she couldn’t imagine behaving otherwise, so to her mind there was nothing to explain. She once wrote that she simply acted out of a “feeling of humanity and comradery.”

Initially, her motivations were perhaps personal: after saying tearful goodbyes to friends as they prepared to leave for the ghetto, she searched for a way to penetrate its security to visit them. Once she started to visit the ghetto regularly, her mission broadened, and she began to undertake helping anyone she could.

Šimaitė lived according to a strict moral code – she never lied, she abhorred the feeling of indebtedness or dependence, and she absolutely rejected the pursuit of wealth or material gain. This code and a strong individualism are what defined the choices she made in her life.

Šimaitė is hailed as a heroine, yet you present her as a flawed human being.

I set out to create a nuanced portrait of a woman who acted with astounding courage, but who was nevertheless human. Early in my research, I came across a letter that Šimaitė concluded by writing, “love me with all my faults.” “What faults?” I wondered, “What is she referring to?” But, of course, we all have faults. They are what make us human. Šimaitė’s deep sense of compassion and capacity for forgiveness came from her understanding of this fact.

Some say the rescuers were saints, yet we learn from your book that Šimaitė would have hated being beatified. Why?

I imagine Šimaitė found it difficult to take pride in saving those she did since so many others perished, including some people very close to her. Perhaps her acts of resistance seemed to be drops that just disappeared into a vast ocean of tragedy and cruelty.

Šimaitė was tortured and confined in the camp at Dachau, yet didn’t want to talk or write about that. Can you share your thoughts on how a person – or a nation – engages with painful memories?

Šimaitė’s experience at Dachau constitutes the great silence in her writing and life. With the exception of a handful of passing references in her letters and diaries, she breathed nothing of her time there. Though I’m no psychologist, I believe this silence is indicative of a very deep trauma. For her, Dachau marked the limit of what was sayable and writeable.

In the end I decided not to try to fill Šimaitė’s silence, but to write around it, and give an image of how her camp experiences echoed throughout the rest of her life. I suppose you could say I tried to create a kind of chalk outline of her camp experience. The book traces the limits of that experience, but doesn’t try to fill in the void. I chose to respect her right to silence, and to consider silence itself as a subject worthy of contemplation.

In your book, you say you’re engaged in a conversation with Šimaitė. Can you tell us more?

I went to the archives looking for answers to questions about the Holocaust in Lithuania – the country of my parents and grandparents – and came across an incredible and largely untouched collection of Šimaitė’s papers. I was a person with a curious skill set (knowledge of Lithuanian, French, German, Russian; training in literary criticism) that seemed perfectly matched to writing Šimaitė’s life story.

I felt as if Šimaitė had foreseen my arrival, and that she’d prepared for it by saving and archiving her papers. In undertaking the project, we entered into an agreement: in return for my telling her story, Šimaitė would answer some of the questions that had been nagging at me.

Finally, can you describe for us your connection to Lithuania?

Lithuanian was the language of my childhood. I grew up speaking the language at home in Toronto, and I learned to read and write it by attending Saturday schools. Beyond life itself, a knowledge of their language is perhaps the greatest gift my parents gave me.

I’ve been to Lithuania many times, and my relationship to that place is simultaneously one of belonging and alienation. Though I get great pleasure from speaking Lithuanian in shops and restaurants, and though I experience a sense a connection to my ancestors when I walk through the fields they once worked, I nevertheless feel that I don’t really belong there. It may be that writing about Lithuania is a way for me to work through these conflicting sensations.

Now, my relationship to Lithuania and its language is increasingly textual. Like Šimaitė, I spend much of my time alone, with books, and conversing with the dead through their writings and in my imagination.

|

Ellen Cassedy |

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - (0) Comment

Jenifer C. Dillis article:

A visit to our Homeland

through the eyes of 12 American-Lithuanian women

____________________________

Jurate Norkunas

Jenifer, you have captured not only the spirit of Lithuania in your post, but the love we Lithuanians living apart from our Homeland all over the world feel. How wonderful our parents were to fill us with such love and appreciation for their homeland. Thank you for this lovely post. Jurate Norkunas-Aukstikalnis/Boston

____________________________

Roberta

How do I explain my teary eyes to my class of 2nd graders who just returned from PE class as I finished reading this???

There are no words....ok, maybe PRICELESS...but that still doesn't do the story, the photos, the memories…

____________________________

Linas Eitmanas

Love your story and pics!

____________________________

Debbie Kimball

Thank you for sharing your story! I too want to visit my homeland, both my grandparents were from Lithuania, my cousin has visited now i want too, I just need to find the right travel companion and just do it! someday SOON!

Thank you again.

Debbie Kimball-Morrow

(Kimbaldis) (Gregavilage) (sp)

____________________________

Gaile Jucenas Callo Nolan

One of my favorite places on earth!

____________________________

Joyce Kulikowski Wehrwein

I would love to make that trip, maybe 'someday!'

____________________________

Jenifer C. Dillis

I MUST return soon...2007 was so very long ago. The 3000+ photos I had taken need some updating! :)

If anyone would like to view ALL my photos from the Trip of A Lifetime, I have them all on KodakGallery...

Just let me know...:) Aciu for allowing me to revisit my favorite far away home.

Jenifer C. Dillis

There is no "if" only a "when" to describe my return to the home I love from far away...I miss my Baltic Sea...♥

Jenifer C. Dillis

I'm packing my bags right now! Ready to take the plunge into the calm, warm waters of The Baltic...heeeeheeee:)

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

History buffs gather in Lithuania to retrace Napoleon’s disastrous retreat

- Posted by - (0) Comment

![]()

Napoleon’s soldiers at the

Vilnius’ Old Town Hall, 1812.

History buffs from the Netherlands and other European countries have gathered in Lithuania to retrace Napoleon’s disastrous retreat from Russia 200 years ago.

The enthusiasts, decked in period costumes and strolling alongside Napoleon-era carriages, attracted large crowds of onlookers Friday in the Lithuanian capital of Vilnius.

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - (0) Comment

IT’S ALL ABOUT LT-MASSACHUSETTS TODAY…

A visit to our Homeland

through the eyes of 12 American-Lithuanian women

Text & Photos: Jenifer C. Dillis

Founder/Researcher at JCD Photography

Lives in East Bridgewater, Massachusetts

From Brockton, Massachusetts

Please join me and my eight biological sisters and three nieces, as we venture to The Homeland of our four grandparents. Having grown up as “purebred” Lithuanian-Americans, we 16 siblings are gifted to have parents who share their pride with us. (We sisters left our seven brothers back in The States, while we took our trip in June-July 2007).