THE VOICE OF INTERNATIONAL LITHUANIA

|

VilNews has its own Google archive! Type a word in the above search box to find any article.

You can also follow us on Facebook. We have two different pages. Click to open and join.

|

Featured black

- Posted by - (15) Comment

How Chicago became

Lithuania’s second capital

PLUS EARLY 20th CENTURY LITHUANIAN-AMERICAN

SOCIETY TOKENS OF CHICAGO, ILLINOIS

Banner from the website http://www.wttw.com/main.taf?p=1,7,1,1,26

By Frank Passic, Albion, Michigan.

When Lithuania came under Russian control in 1795, the Russians did all they could to “Russify” the Lithuanians, but they were continually met with stiff opposition. During the last half of the 19th Century, oppression increased as parochial schools were closed and Lithuanian printed matter was forbidden. Repressive measures were forced upon the people by the Czar, adding to the misery of the Lithuanian nation which already suffered from famine and mass unemployment.

As a result, thousands of Lithuanians fled their homeland in the late 19th and early 20th centuries prior to World War I. Emigration to America eventually totaled 635,000 individuals, approximately 20 percent of the population of Lithuania! Lithuanians arrived at Ellis Island impoverished, penniless, and unable to speak the English language but full of hope – the hope of freedom, a new life and unlimited opportunity.

Helping the Lithuanian immigrant was the Brooklyn Chapter of the Lithuanian Alliance of America, which gave aid to those at Ellis Island. The Brooklyn Lithuanian-American Citizens Club held a special conference in May of 1911 to plan a strategy for helping those who were scheduled for deportation back to Lithuania. The No. 4 issue of Tevyne (1896) stated, “At present, masses of Lithuanian emigrants are arriving in New York. Every ship from Hamburg brings tens and hundreds of Lithuanians. Many are sent back and the Alliance’s Brooklyn Chapter is working its hardest for the good of those poor peoples…”

In general, the immigrants stayed in New York only briefly, then moved westward to Pennsylvania, where they found employment building railroads and working the coal mines. Numerous Lithuanian organizations, newspapers, and societies were organized in Pennsylvania. These served as the prelude to those that were to be established later in Chicago as Lithuanian immigrants moved westward. Many Chicago societies were actually branches of those that were first established in Pennsylvania.

The first group of Lithuanians came to Chicago in 1870, when eighteen men arrived with a railroad crew. Because of its central location with industry and development, Chicago became the goal of the thousands of impoverished Lithuanian immigrants seeking a new life. Groups of Lithuanians came in 1880 and 1885, with the first colony being established on the North side of the city. After that, the influx of Lithuanians to Chicago grew at an enormous rate. It is estimated that between 1880 and 1914 more than 47,000 Lithuanians settled in the city, congregating in the Bridgeport and Town of Lake districts. By 1923, the Lithuanian population had grown to over 90,000, confirming the fact that Chicago contained the largest Lithuanian population of any city in the world, even more than Kaunas, Lithuania.

According to one story, the Bridgeport section, where many Lithuanians settled, was supposedly named after a Lithuanian immigrant from Tilsit (East Prussia/ Lithuanian Minor) named Ansas Portas. Portas owned land on the south side of the Chicago River at a bridge crossing, and people referred to the area as the “bridge to Portas,” which was later changed to Bridgeport. The Bridgeport section served as the nucleus of the Lithuanian community from the early years of immigration to Chicago through the era of World War I.

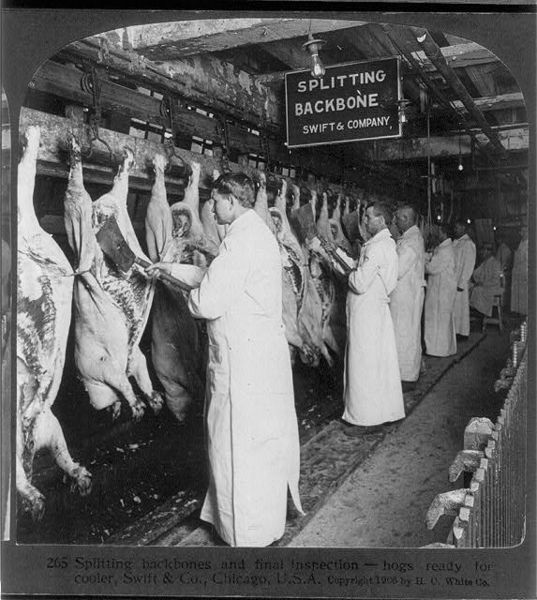

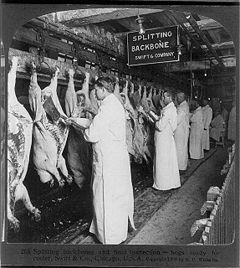

Due to the difficulty they had in obtaining jobs, Lithuanian immigrants began to settle around the stockyards where work was available in the slaughterhouses and steel mills. By World War I, approximately 25 percent of the ethnic work force in the industries was Lithuanian, and it is estimated that a total of 100,000 Lithuanians worked in the stockyards in Chicago during their existence. The grim and horrible conditions Lithuanian workers faced there were the theme of the classic novel, The Jungle (1906) by Upton Sinclair.

The Lithuanian contribution to the city of Chicago is significant in several ways. First, it provided the city with an added labor base upon which the city’s industries grew and prospered. Second it accelerated the building of ethnic neighborhoods, adding to the distinctive variety found in the city’s cultural life. Third, it spurred the formation of new businesses and more affluence.

The Union Stockyards were at one time a significant employer of Chicago's

Lithuanian community. Upton Sinclair's 1906 novel The Jungle, revolves around the life of a Lithuanian immigrant working

the Stockyards named Jurgis Rudkus.

The Lithuanian immigrants to Chicago frequently made their habitats close to the Catholic churches, which gave them a certain moral and material support. The first waves of Lithuanian immigrants associated with already established Polish parishes. However, as the Lithuanian national consciousness became stronger and friction with the Poles increased, a large number of conflicts and disputes arose between and Lithuanians who were members of the same parish. The main area of conflict centered around the question of whether Lithuanian or Polish would be the language of sermons and confessions.

These disputes became severe and even violent. The press of the day frequently reported these incidents in public newspapers. For example, in 1877 in Shenandoah, Pennsylvania, the Lithuanian church members barricaded themselves in the church and would not allow the Polish pastor to enter. In Freeland, Pennsylvania in 1894, a fight ensued between Lithuanian and Polish parishioners, in which the participants exchanged revolver shots, several persons were wounded, and the police had to intervene. As many of these Lithuanian immigrants moved west to Chicago, they were determined to establish their own parishes, independent of Polish influence.

Despite many handicaps, early Lithuanian immigrants did establish their own native-language parishes, newspapers, societies, businesses, taverns, and organizations, all of which contributed to the emergence of the ethnic Lithuanian in American society. Many of these early societies, which have long since disappeared, issued small token “chips” which were good for a purchase at the particular establishment. These tokens are a lasting memento of the early history of the Lithuanian immigrant to the city of Chicago. They are a reminder of the bond of national identity that caused people to band together in fraternal organizations as they adjusted to their new life in America.

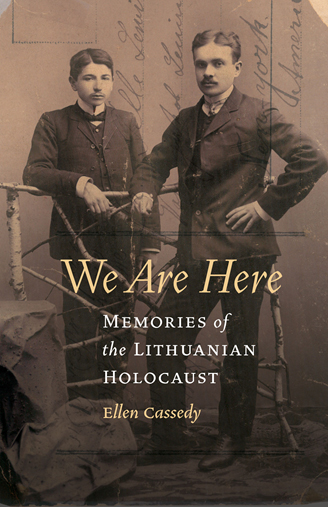

The collection of Lithuanian American society tokens presented here was originally assembled by the late Dr. Alexander M. Rackus (1893-1965), himself an immigrant who came to Chicago. A member of the American Numismatic Association, Rackus served as historical/numismatic curator of the Vytautas the Great Museum in Kaunas, Lithuania, 1936-1940. A listing of his Chicago lodge tokens appeared in the November, 1948 issue (No. 4) of the American-Lithuanian Philatelic Specialist, which Dr. Rackus published in Chicago after the War. However, the collection mysteriously disappeared over the years and was feared lost. In September of 1979 it was discovered in a small box behind some shelves in a closet, in the archives of the Balzekas Museum of Lithuanian Culture (which had purchased Dr. Rackus’ collection just prior to his death) at its original location at 4012 Archer Avenue in Chicago. In the same box were also early Lithuanian society tokens from Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, and Brooklyn, New York. Since that discovery, the collection has been cataloged, photographed and placed on permanent exhibit at the Museum at its present location at 6500 S. Pulaski Rd. in Chicago.

As the reader will discover, these small tokens display various inconsistencies, spelling errors, and poor grammar. Many of the spelling variances are due to the heavy Polish influence under which the Lithuanians tried to establish their own separate identity. Though the Lithuanian written language was being purged of Polish influence, that influence still shows up on many of these tokens. For example, the Lithuanian letter “s” which is “sh” in English, comes out as a Polish “sz” on the text of some of the tokens. The word “Lietuvos,” meaning “Lithuanian,” comes out as a Polish influenced “Lietuwiszku,” or with other variances. In addition, in the Lithuanian language there is no letter “w,” but the letter “v” is used. Yet the letter “w” shows up on numerous tokens. These are just a few of the many interesting “problems” which occur on these tokens.

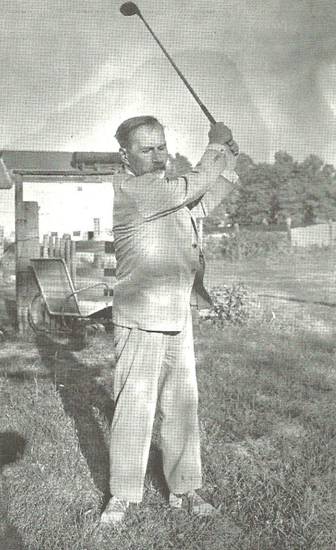

1935 photo of Dr. Alexander M. Rackus (1893-1965) who originally assembled the

collection cataloged here.

The following is a catalog of Lithuanian society tokens of Chicago with historical notes on the societies that issued them.

1. Society of Saint George the Knight

Aluminum,

26 mm.

Obverse inscription: DR-TE SZV. IURGIO R. ir K. CHICAGO, ILL. With dotted line

border.

Full meaning: Draugiste Szvento Jorgio Riderio ir Kankinio

Translation: Society of Saint George the Knight and Martyr.

Reverse: A large cipher 5 in the center, encircled by 16 five pointed stars.

In 1881 several Lithuanian families settled in the area around Noble Street and attended the nearby Polish churches. Wishing to establish their own independent Lithuanian language society, the Society of St. George the Knight was founded in 1884 as the first Lithuanian organization in Chicago. However, several of its members moved elsewhere, and the group disbanded. In March of 1891 the society was revived, and in 1892 the first Lithuanian Roman Catholic church in Chicago was built at the corner of Auburn (now Lituanica) Avenue, at 33rd Street. The first parish priest was Father Valentinas Cizauskas, who raised funds for the structure. The wooden church was erected in 1892 under the direction of Father Jurgis Kolesinkis.

St. George’s Church, the first Lithuanian Roman Catholic Church in Chicago.

This brick structure was erected in 1902 during the pastorate of Father

Mateusas Kriauciunas.

A relief of St. George the Knight slaying the dragon guards the entranceway to

St. George’s Church.

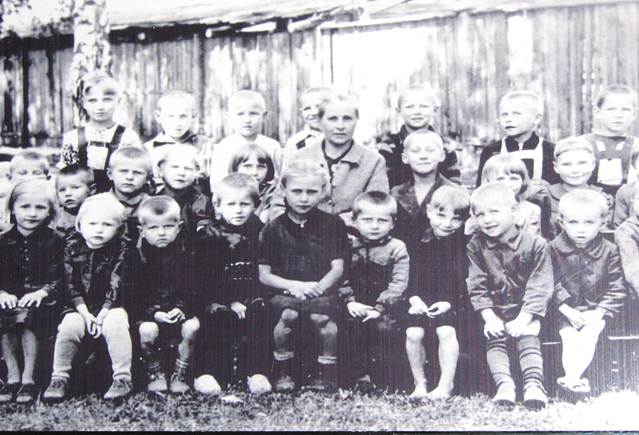

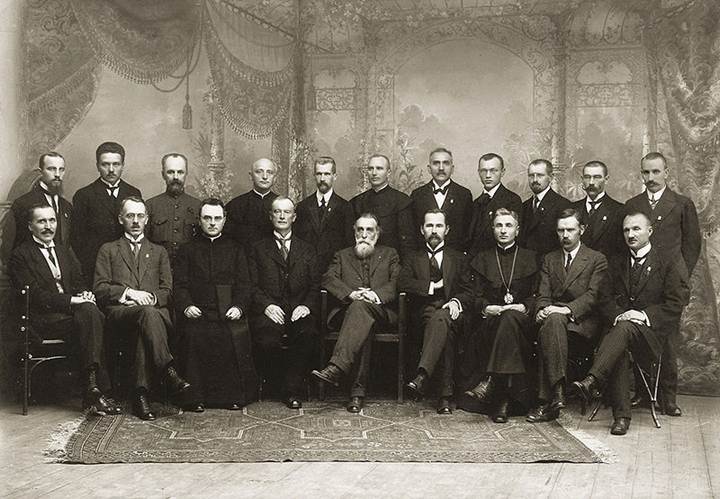

Fund raisers at St. Michael’s Church pose for a portrait in 1916.

2. Society of Saint Stephen

Aluminum,

double oval, 15 x 19mm. Beaded border.

Obverse inscription DRAUGISTE SZVENTO STEPONO.

Translation: Society for Saint Stephen.

Reverse: GOOD FOR 5¢ IN TRADE, encircled by a beaded border.

The St. Stephen Lithuanian Society was organized in December 16, 1905.

3. Society of St. Michael The Archangel No. 2

Aluminum,

26mm. Dotted border.

Obverse inscription: DR. SV-TOM-LO ARKANIOLO NO. 2.

Full meaning: Draugiste Szvento Mykolo Arkaniolo No. 2.

Translation: Society for Saint Michael the Archangel No. 2.

4. Society of All Saints

Aluminum,

octagonal. 25 x 27mm. Dotted border on obverse.

Obverse inscription: DR-TES VISU SZVENTU KOWOS 17d 1906

Full meaning: Draugistes Visu Szventu Kowos 17 diena 1906.

Translation: Society of All Saints, March 17th day, 1906.

Reverse: A large cipher 5, surrounded by a beaded border.

The All Saints parish was founded in the Roseland section of Chicago in 1906.

5. Knights of the Lithuanian King Mindaugas

Aluminum,

25mm. Beaded border both sides.

Obverse inscription: K. L. K. MINDAUGIO PRIE PARAP SZW. JURGIO K.

Full meaning: Kareiviai Lietuvos Karaliaus Mindaugio Prie Parapijos Szwento

Jurgio Kareiwio

Translation: Knights of the Lithuanian King Mindaugas at Saint George the

Knight Parish.

This society, one of several growing out of the St. George’s parish, is thought

to have issued this token around 1906.

6. Society of Saint Prince Casimir

Aluminum,

26mm. Dotted both sides.

Obverse inscription: DR. TE. SV. K. KAZIMERIA 5¢

Full meaning: Draugiste Svento Karalacio Kazimiero 5¢

Translation: Society of Saint Prince Casimir

Reverse: The reverse is blank, except for the dotted border.

On October 24, 1886, twelve Lithuanians met at 668 Noble Street, and founded

the second Lithuanian society, St. Casimir’s. The society was formed for the

purpose of saying confessions to the priests in the native Lithuanian language.

With the money raised by the Saint Casimir Society, priests from other cities were

paid to provide the Chicago Lithuanians with Easter services in their native

language. One of these was Father Valentinas Cizauskas, who later became the

pastor of the St. George’s parish.

7. St. Casimir Society

Aluminum,

25mm. Dotted border both sides.

Obverse inscription: ST. KAZIMIERA DRUGGISTE UZDETA UZDETA 1921 M CHICAGO, ILL.

Full meaning: Svento Kazimiero Draugiste Uzdeta 1912 year, Chicago, Ill.

Translation: St. Casimir Society established in the year of 1912, Chicago,

Illinois.

Reverse: A very large cipher 5 in the center.

This society was organized in the West Side of Chicago on March 4, 1912, and

its main purpose was mutual assistance and importing books published by the St.

Casimir Society in Kaunas, Lithuania.

Notice the misspelling of the word Draugiste as “Druggiste.” Was the die maker

thinking of the English word druggist?

8. Society of the Grove of Lithuania

Aluminum,

25mm. Dotted border obverse, beaded border reverse.

Obverse inscription: DRAUGISTE LETUVOS GOJAUS

Translation: Society of the Grove of Lithuania

Reverse: A large cipher 5

Undated. This organization had its origin in Pennsylvania, with a branch in

Chicago.

9. National Guard of the Lithuanian Grand Duke Algirdas

Aluminum

crenated, 25 x 30mm. 8 petals. Dotted border obverse, beaded border reverse.

Obverse inscription: L.G.D.L.K. ALGIRDA CHICAGO ILL.

Full meaning: Lieb Gvardija Dijiojo Lietuvos Kunigaikscio Algirdo, Chicago,

Ill.

Translation: National Guard of Grand Duke of Lithuania, Algirdas, Chicago,

Illinois.

Reverse: GOOD FOR ONE 5 (cent) DRINK

This organization was named after Lithuanian Grand Duke Algirdas It was

semi-militaristic in nature, very patriotic, and very anti-Russian.

10. Saint Domininks Society

Aluminum

crenated, 25 x 30mm. 8 petals. Beaded border both sides.

Obverse inscription: ST. DOMININKS SOCIETY CHICAGO.

Reverse: GOOD FOR 5 (cent) DRINK.

The St. Dominink’s Society was organized on November 24, 1910, in the

Bridgeport section of Chicago. The majority of the members were from the

Samogitian area of Lithuania, from the city of Raseiniai.

11. Society of St. Stanislaus Bishop and Martyr

Aluminum

crenated, 26 x 30mm. 8 petals. Beaded border obverse, dotted border reverse.

Obverse inscription: DR-TE. SZ. SLANISLOWA V. IRK. CHICAGO, ILL.

Full meaning: Draugiste Szwenta Stanislowa Vyskupa ir Kankinia. Chicago, Ill.

Translation: Society of Saint Stanislaus Bishop and Martyr.

Reverse: GOOD FOR 5¢ IN TRADE.

This was one of the strongest fraternal lodges in the Bridgeport section and

was organized on July 6, 1903. The inscription is in the Samogitian dialect.

Note the misspelling of the word “Stanislowa” on the tokens. It starts out as

Sl instead of St.

12. United Lithuanian Societies

Aluminum,

24mm. Dotted border both sides.

Obverse inscription: SUSIWIENIJIMAS LIETUWISKU DRAUGISZCZIU CHICAGO, ILL.

Translation: United Lithuanian Societies, Chicago, Illinois.

Reverse: GOOD FOR 5¢ IN TRADE.

The U.L.S., the Chicago branch of the Lithuanian Alliance of America, was

established in 1900. In 1906 the Alliance’s national conference was held in

Chicago. An offshoot of this group was the Lithuanian Roman Catholic Alliance

of America, which established a Chicago branch at St. Michael’s church in 1907.

13. Society of the Lithuanian King Mindaugas

Brass,

25mm. Dotted border both sides.

Obverse inscription: DR-ST. L.K. MINDAVGIA CHICAGO, ILL.

Full meaning: Draugiste Lietuvos Karaliaus Mindaugio, Chicago, Ill.

Translation: Society for the Lithuanian King Mindaugas, Chicago, Illinois.

Reverse: GOOD FOR 5¢ IN TRADE AT THE BAR.

This organization was founded on March 18, 1909, and should not be confused

with the St. George’s parish Mindaugas organization that issued token No. 5.

The Providence of God church and school.

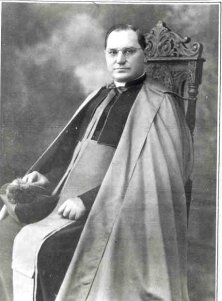

Father Michael Krusas (1879-1950), one of Chicago’s most formidable Lithuanian

priests.

14. The Providence of God Society

Brass,

21mm. Dotted border obverse, plain border reverse.

Obverse inscription: PROVIDENCE OF GOD SOCIETY, with an all seeing Eye of God

in the center.

Reverse: GOOD FOR 5¢ DRINK.

The Providence of God Society was organized in 1900. Located at 717 W. 18th St.

and Union Avenue, a combined church and school was erected in 1901, and 1905

the parish rectory was opened under the direction of Father Edward Steponavicius.

One of the parish’s most formidable priests in the early years was Father

Michael Krusas (Kruszas) (1875-1950). Under Krusas’ direction, the church

building was erected in 1914. It still stands today, just west of the Dan Ryan

Expressway, where it can be seen from the highway. Krusas later became the

pastor of St. George’s church, and was one of the highly respected church

leaders in Chicago. In 1979 the Providence of God parish had the high honor of

being visited by Pope John Paul II during a tour of America. In a personal

sidelight, it was at the original church-school building (pictured above on the

left) that this writer’s maternal grandparents, Nikodemas and Teodora

(Barvydaite) Kulikauskas were married on January 8, 1914 by Fr. Krusas. Nikodemas

was born near Varniai, Lithuania and came to America in 1911, while Teodora was

from near Luoke, Lithuania and arrived in Chicago in 1913.

15. and 16. Grand Duke Gediminas Society

Brass,

octagonal. 27 x 29mm. Grooved dotted border both sides.

Obverse inscription: DR. D.K. GEDEMINO

Full meaning: Draugiste Didzijo Kunigailkscio Gendemino

Translation: Grand Duke Gediminas Society.

Reverse: No. 15: 10¢, surrounded by twelve stars. No 16: 50¢ surrounded by

twelve stars. Note: other tokens were issued in denominations of 5¢, 25¢, 75¢

and $1.00.

The Grand Duke Gediminas Society was organized in the Bridgeport section of the

city in 1891. It was named Grand Duke Gediminas (1275-1341), a famous

Lithuanian Grand Duke who founded the capital city of Vilnius in the year 1323.

17. Society of Brothers and Sisters of Lithuania in America

Brass,

octagonal, 27 x 30mm. Dotted border obverse, beaded border reverse.

Obverse inscription: DR. LIETUVOS BROLUI IR. SESSERU AMERICA 12 D RUG 1911

Full meaning: Draugiste Lietubos Broliu ir. Seseru Amerikoje 12 Diena Rugsejo

1911.

Translation: Society of Brothers and Sisters of Lithuania in America, 12th day

of September, 1911

Reverse: GOOD FOR A 5 CENT DRINK

18. 19. and 20. Saint Martins Theatrical Society

Brass,

23mm. square.

Obverse description: All three tokens bear the same inscription, ST. MARTIN’S

SOCIETY.

No. 18 bears a beaded circular border, and the inscription is diamond shaped in

relation to the planchet. In the center is a five pointed star with two

diamonds on the sides, and 3 dots on top.

No. 19 bears a corded border, and the inscription is horizontal in relationship

to the planchet. There are only 2 dots above the center ornamentation. No. 20

is very similar to No. 18, but several differences do occur. The position of

the lettering is different: note the letter “I” in “society” is shifted to the

left under the star. The border is crenated instead of being beaded.

The die used for No. 20 is about 2mm smaller than No. 18. Reverse description:

GOOD FOR 5¢ IN TRADE.

St. Martin’s Society was officially known as Draugiste Treatraliszka Po

Preigloba Szwanto Martino, which translates “Theatrical Society Under

Protection of St. Martin.” The chief purpose of this organization was to

provide Lithuanian entertainment in the form of acting and plays. Organized on

January 22, 1899, in the Bridgeport section, this organization had a large

library consisting of many thousands of Lithuanian books. It finally merged

with another Lithuanian organization in 1928, after 29 years of fine cultural

existence.

21. Lithuanian Theatrical Society of St. Martin

Aluminum,

25mm. Obverse bears a fine line border, the reverse has a dotted border.

Obverse inscription: LIET. TEAT. DR-TE SZ. MARTINO CHICAGO, ILL. A pair of

clasped hands is depicted in the center.

Full meaning: Lietuviszka Teatraliszka Draugiste Szvento Martino, Chicago,

Illinois.

Translation: Lithuanian Theatrical Society of Saint Martin, Chicago, Illinois.

Reverse: In the center, AMATORIUS, meaning, Amateur.

These tokens were given to the stage actors and workers who used them towards

the purchase of refreshments.

22. Saint Roch’s Mutual Benefit Society

Brass,

double oval, 24 x 28mm. Both sides bear a dotted border.

Obverse inscription: DRAUGISTIE ROKO SZWENTA 1903.

Translation: St. Roch Society, 1903

Reverse: GOOD FOR 5¢ IN TRADE.

The Saint Roch Mutual Benefit Society was organized in the Town of Lake

district of Chicago on January 3, 1903. Most of the members were from the

Samogitian (Zemaitija) region of Lithuania. St. Roch’s was named after Saint

Roch, a Frenchman who cared for persons in plague-stricken Italy in the 14th

century. The St. Roch fraternity was established in Lithuania in 1705 with the

headquarters established in Varniai, Lithuania, in 1743. Its purpose was to

nurse the sick and collect donations for the poor. The St. Roch’s society in

Varniai was forcibly closed by the Russian Czar in 1886. The Samogitian

Lithuanians who came to the U.S. in the spirit of their original society,

re-established it in Chicago.

Our Lady of Vilnius Parish on West 23rd Place.

23. Our Lady of Vilnius of the Dawn Gate

Bronze,

octagonal 25 x 27mm. The obverse has dotted border; the reverse a beaded

border.

Obverse inscription: DRSTE AUSZROS VARTU S.M.P. 2 DA BERZ. 1906 CHICAGO, ILL.

Full meaning: Draugiste Auszros Vartu Szvencziausios Marijos Panos 2 Diena

Berzelio 1906, Chicago, Illinois.

Translation: Society of the Blessed Virgin Mary of the Dawn Gate, 2nd Day of

June, 1906, Chicago, Illinois.

Reverse: GOOD FOR 5¢ AT THE BAR.

The Our Lady of Vilnius church was founded on the West Side of Chicago after

several years of preliminary meetings with the Catholic hierarchy to determine

the need for a parish and school. In January of 1906 Archbishop Quigley

authorized Rev. Casimir Ambrozaitis to establish the Lithuanian parish. In

August of 1906 the parish purchased land at 2327 W. 23rd Place, between Western

and Oakley Aves. On October 5, the ground was broken for a school, with the

cornerstone being laid on November 11. In 1907 the church building was

dedicated. The church was named after the famous Dawn Gate Shrine located in

Vilnius, Lithuania.

24. 25. and 26. Lovers of the Fatherland Lithuanian Society

No. 24:

Brass, 25mm. No. 25: Aluminum octagonal, 24 x 27mm. No. 26: Brass escalloped,

25 x 30mm. 8 petals. No. 24: 5¢; No. 25: 10¢; No. 26: 25¢.

Obverse: The inscription on all three tokens reads, T.M.L. DR-TES CHICAGO, ILL.

Full meaning: Tevynes Myletoju Lietuviu Draugistes Chicago Illinois.

Translation: Lovers of the Fatherland Lithuanian Society, Chicago Illinois.

Reverse: In the center of all three the denomination numeral (5, 10, 25) is

within a radiant star. Established in Pennsylvania in 1896, this group was

originally founded by Jonas Sliupas (1861-1944), a well known figure among

Lithuanian-Americans. The Chicago branch was founded a year later on April 28,

1897. In this 1948 listing, Dr. Rackus states that members of this group

“fought the church.”

27. Lithuanian National Society

Bronze

octagonal, 25 x 27mm. Both sides bear a dotted border.

Obverse inscription: LIETUVISZKA TAUT. DRAU-TE 5¢ VIENYBE.

Full meaning: Lietuviszka Tautiszka Draugiste Vienybe.

Translation: Lithuanian National Society. 5¢. Unity.

Reverse: The inscription appears in the English language, with the exception of

the word VIENYBE being printed in Lithuanian at the bottom.

28. Butvill Tavern

Aluminum,

24mm. Both sides bear a dotted border.

Obverse inscription: BUTVILL TAVERN 3327 ARCHER AVE.

Reverse: GOOD FOR 10 ¢ IN TRADE.

This token was issued in 1938 by the tavern of Mr. Butvilas, and is a reflected

of the population shift of the Lithuanians in Chicago towards other sections of

the city.

29. Women’s Society of the Dawn Gate

Bronze

crenated, 25 x 30mm. 8 petals. The obverse has a dotted border; the reverse,

beaded.

Obverse inscription: M.D.S.P.M.A.V.

Full meaning: Moteru Draugiste Szvento Panos Parijos Auszros Vartuose.

Translation: Women’s Society of the Blessed Virgin Mary of the Dawn Gate.

This token was issued by the same parish that issued token No. 23. The parish

in Chicago was one of five in the U.S. named after this Lithuanian shrine.

This listing of Lithuanian lodges in Chicago is not exhaustive. Other tokens were issued by such organizations as: “The Lithuanian Sons and Daughters Hall” on South Halsted, the “Lithuanian American Republican League,” and others. These tokens frequently appear as “mavericks” in coin dealers’ token boxes, and it takes a dedicated collector to know how to find them.

There were three other items that were minted by early 20th century immigrants which although not tokens, should be mentioned here. The first is the medal issued as part of a ribbon in 1907 by the Women’s Society of the Dawn Gate (same group as token 29).

Bronze with loop, 31mm.

Obverse inscription: STEBUKLINGA S. P. VILNIUS AUSTROS VARTUSE.

Translation: Miraculous Blessed Virgin of Vilnius of the Dawn Gate.

Reverse inscription: LIETUVOS GLOBIEJI MELSTIS UZ MUMIS MOTERU DRAUGYST UZDIETA

LAPK. LL. 1907. WESTSIDE, CHICAGO, ILL.

Translation: Patroness of Lithuania, Pray for Us. Women’s Society, Begun November

1907.

This society ceased to function in 1936.

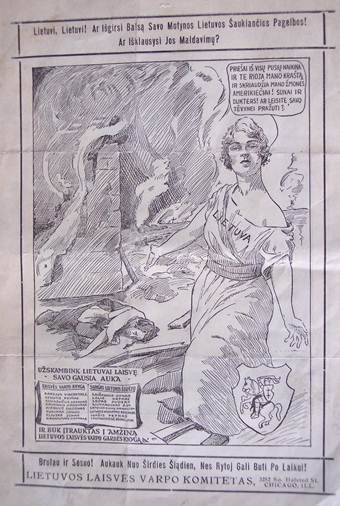

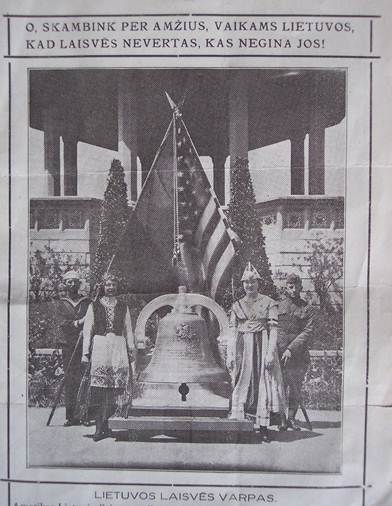

The Lithuanian Congress held in Chicago, June 8-11, 1919, approved the gift of a cast bell from Lithuanian Americans to their fatherland. The 1200 pound bell, modeled after the Liberty Bell in Philadelphia, was paid for by donations from Lithuanian Americans and was shipped to Kaunas on January 12, 1922. It was rung for the first time on February 16, 1922, Lithuania’s Independence Day. Those who contributed $5 or more to the construction of the bell were eligible to acquire the Lithuanian Liberty Bell’s Honor Badge, a bronze medal with ribbon and pin-back bronze bar. The striped ribbon is yellow, green and red, the three colors of the Lithuanian flag and the bell depicts the Vytis national emblem of Lithuania.

Bronze, with bar and ribbon, 4mm.

Bar inscription: LAISVE LIETUVAI

Translation: Freedom for Lithuania

Bell inscription: O, SKAMBINK PER AMZIUS VAIKAMS LIETUVOS KAO LAISVES NEVERTAS

KAS NEGINA JOS

Translation: Ring through the ages for the children of Lithuania, that worthy

of freedom is he who fails to defend it.

The year 1930 marked the 500th anniversary of the death of Lithuania’s greatest

patriarch, Vytautas the Great. In Lithuania in 1930, a year-long celebration

was held, commemorating the anniversary of Vytautas’ death.

The Lithuanians in Chicago issued a special medal/badge to commemorate the

event. Struck in both bronze and aluminum, each bore a cloth ribbon-pin bearing

the colors of the Lithuanian national flag: yellow, green, and red.

Bronze or aluminum, 30mm.

Obverse inscription: VYTAUTAS DIDYSIS LIETUVOS KUNIGAIKSTIS with a bust of

Vytautas in the center.

Translation: Vytautas the Great, Lithuanian Grand Duke.

Reverse inscription: 500th ANNIVERSARY OF THE DEATH OF VYTAUTAS. 1430-1930.

CHICAGO, ILL. In 1979 a hoard of these medals surfaced at the Balzekas Museum

in Chicago, and the majority of them were subsequently sold to collectors. The

bronze version of this medal is much scarcer than the aluminum.

Special thanks to the Balzekas Museum of Lithuanian Culture in Chicago for providing information for this article.

Lithuanians in the Chicago areaFrom Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia The Union Stockyards were at one time a significant employer of Chicago's Lithuanian community. Upton Sinclair's 1906 novel The Jungle, revolves around the life of a Lithuanian immigrant working the Stockyards named Jurgis Rudkus. Lithuanians in Chicago and the nearby metropolitan area are a prominent group within the "Windy City" whose presence goes back over a hundred years. Today Chicago possesses the largest Lithuanian community outside Lithuania,[1] who have dubbed the city as Little Lithuania, and many Lithuanian-Americans refer to it as the second capital of Lithuania. Lithuanian-Americans from Chicago have had a significant impact on politics in both the United States and Lithuania.

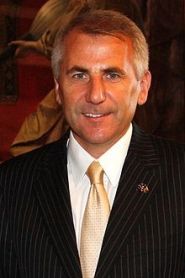

[edit]HistoryLithuanians have been documented as arriving in the US since 1918, when Lithuania re-established its independence from Imperial Russia.[1] Although this is the first official record, Lithuanians began arriving at least two decades earlier; however, they were listed as Russian citizens.[1] This is compounded by the fact that, prior to Lithuanian independence, most if not all official documents were written in Russian,Polish or German. Thousands of Lithuanians have since moved to Chicago, providing a good source of labor for the growing city. The Lithuanian community in Chicago was most famously immortalized byUpton Sinclair in his 1906 novel about the treatment of workers in the Chicago stock yards, The Jungle, whose story revolves around telling the life of a Lithuanian immigrant named Jurgis Rudkus. [edit]DistributionThe first and most prominent Lithuanian enclave in Chicago was called "Lithuanian Downtown" which was located along Halsted street in Bridgeport and founded by Lithuanians who settled nearby their Old World neighbors, the Poles, who were located in a Polish Patch in the vicinity of St. Mary of Perpetual Help.[2] It was here that the Lithuanian church of Saint George was founded as the first Lithuanian parish in the Midwest, foreshadowing the prominence that Bridgeport would play as one of the key centers of Lithuanian activity throughout the United States.[3] A large number of the early buildings of this district were built by the first prominent Lithuanian community leader, Antanas Olšauskas (pronounced Ole-shau-skus), circa 1910.[2] Centered on Thirty-third and Halsted, Bridgeport was Chicago's leading Lithuanian neighborhood from the 1890s through the 1950s. Although the numbers of Lithuanians in the area began to fall off in the 1950s, one of Lithuanian Chicago's longtime institutions, Healthy Food Restaurant, still remains on Halsted near Thirty-second street.[2] Although Lithuanians initially settled in areas adjacent to the ethnic group most familiar from their European homeland, the Poles, a pattern consistent with most other immigrant groups in Chicago, the Lithuanian community today is found all over theChicago metropolitan area. There have been a number of Chicago neighborhoods in which Lithuanian immigrants have clustered during the 20th century, including Bridgeport, Brighton Park, Marquette Park, and the Back of the Yards. The adjacent near-western suburb of Cicero had an enclave of Lithuanians in the 20th century, especially around St. Anthony's Parish. The most recent wave of immigrants has settled in the Chicago suburbs of Lemont, Darien and Woodridge. There is a small enclave of Lithuanians around the Beverly Shores area in northwest Indiana at the southern coast of Lake Michigan. [edit]SignificanceValdas Adamkus was an active member of the Lithuanian community in Chicago for decades before becoming President of Lithuania. Today "Little Lithuania" is the center of Lithuanian culture in North America. It houses the only museum about Lithuanians in the Western Hemisphere, the Balzekas Museum of Lithuanian Culture, which provides a wealth of information about Lithuania and Lithuanian culture. Little Lithuania has a number of Lithuanian restaurants, bookstores, and other shops. The former president of Lithuania, Valdas Adamkus1998-2003 and 2004–2009, is a former resident of the Chicago area as well. Chicago is home to the Consulate General of the Republic of Lithuania, and the city's large Lithuanian-American community maintains close ties to what is affectionately called the Motherland. Chicago's Lithuanian heritage is visible in the cityscape through its Lithuanian-named streets such as Lituanica Avenue and Lithuanian Plaza Court as well as an Art Deco monument in Marquette Park commemorating pilots Stasys Girėnas and Steponas Darius who died in the crash of the Lituanica in 1933. A number of the most architecturally significant churches of the Archdiocese of Chicago were built as national parishes by Lithuanian immigrants such as Holy Cross, Providence of God, and Nativity B.V.M., which is dedicated to our Our Lady of Šiluva or the now demolished St. George's in Bridgeport. Opulently decorated with a proclivity towards Renaissance and Baroque ornamentation, Lithuanian churches were designed in the spirit of the architecture of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth's heyday. Like Chicago's Polish Cathedral's, these churches were statements meant to recall an era when the Grand Duchy of Lithuania spanned from the Baltic to the Black Sea, having been built at a time when Lithuania was under Russian occupation and incorporating Lithuanian imagery in its decor such as the Vytis to invoke pride in Lithuanian culture. There are many Lithuanian schools built near and in Chicago. Chicago Lithuanian Youth Center (Čikagos Lituanistinė Mokykla), a private school for Lithuanian immigrant children was founded in 1992. Other Lithuanian schools include Maironis in Lemont, Gediminas in Waukegan and Rasa in Naperville. There are also many Lithuanian newspapers circulating around Chicago, like Draugas (Friend), Čikagos Aidas(Echo Chicago), Langas (Window), Amerikos Lietuvis (Lithuanian American), and Vakarai (The West). Years ago, the Lithuanian Song festival (Dainų Šventė) and Dance Festival (Šokių Šventė) have been held at the now-demolished International Amphitheatre, originally near the Stockyards on the south side of Chicago. More recently, the Song Festival has been held at the UIC Pavilion a couple of times and the Dance Festival held in the suburb of Rosemont, not far from Chicago O'Hare Airport. The Lithuanian Opera Company of Chicago was founded by Lithuanian emigrants in 1956,[4] and presents operas in Lithuanian. Lithuanian operas were sometimes held at Maria High School in Chicago, a school that has been associated with Lithuanians, and such operas are now sometimes held at Morton East High School in Cicero. Draugas building in Chicago, IL § Lithuanian World Center (Pasaulio Lietuvių Centras, 14911 127th St.) in Lemont, Illinois - a complex for Lithuanian culture including a sizeable Roman Catholic chapel, Matulaitis Mission, and classrooms for a Lithuanian school on Saturdays, as well as various other facilities.[6] § Lithuanian Youth Center (Lietuvių Jaunimo Centras, 5620 S. Claremont Ave.) in Chicago's Marquette Park neighborhood on the Chicago south side. At this location, there is a Jesuit Residence for Catholic Fathers and Brothers, the Youth Center, a Roman Catholic chapel, the Čiurlonis Gallery (Čiurlionio Galerija), and the Lithuanian Research and Studies Center, Inc. [Lituanistikos tyrimo ir studijų centras (LTSC)].[7][8] For a photo, see here. § Consulate General of the Republic of Lithuania in Chicago (Lietuvos Respublikos generalinis konsulatas Čikagoje at 211 E. Ontario St., Suite 1500) on the very near north side of Chicago. § Ateitis Foundation Center (Ateitininkų Namai, 1380 Castlewood Drive) in Lemont, Illinois - a facility for the Lithuanian youth organization whose members are Ateitininkai.[9] For photos of the center building, seehere and here. § Balzekas Museum of Lithuanian Culture (Balzeko lietuvių kultūros muziejus) on Chicago's south side. § Draugas Publishing House (Draugo Redakcija) not far from the Midway Airport area on the Chicago west side - facility where the publication of the century-old Lithuanian language daily newspaper Draugastakes place. § St. Casimir Lithuanian Cemetery (Švento Kazimero Kapinės at 4401 W. 111th Street) is a Lithuanian cemetery of the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Chicago on the edge of the southwest side of Chicago where many deceased Lithuanians are buried.[10] [edit]References1. ^ a b c Čikagos aidas. The Lithuanian Market. Retrieved on 2008-09-04 2. ^ a b c http://www.ahsd25.k12.il.us/curriculum%20Info/Neighborhoods/bridgeport1.htm 3. ^ http://www.ahsd25.k12.il.us/curriculum%20Info/Neighborhoods/bridgeport2.htm 4. ^ "About the Lithuanian Opera Company, Inc. in Chicago". Lithuanian Opera Co.. Retrieved 2006-09-14. 6. ^ Pasaulio Lietuviu Centras | Lithuanian World Center | 7. ^ BalticJesuit 8. ^ LTSC - Lituanistikos tyrimo ir studiju centras, Chicago, IL 10. ^ Lithuanian Parishes of the Roman Catholic Diocese in America [edit]External links§ The Balzekas Museum of Lithuanian Culture § The Consulate General of the Republic of Lithuania

|

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - (1) Comment

Amrita Nadi: When researching for the Wisdom of Laughter Album (soon coming), I had delight of "meeting" Teresa Hsu, 112 years old, who inspires with her simple messages of joy. "if you love everybody with all the love in your heart, then you’ll be happy, ha, ha, ha,” Below is a wonderful report on her meeting with an audience in 2010, from the blog of Tsem Tulku Rinpoche

The power of laughter

Teresa Hsu

By K. Kaewuni Dewi

CENTENARIAN Teresa Hsu kept some 200 people in stitches during her talk on ‘Love All Serve All’ at the Malaysian Buddhist Association hall in Penang last Friday.

For the bubbly Chinese-born Singaporean, who is affectionately known as Singapore’s Mother Teresa, laughter is definitely the best medicine.

Born in 1898, the 112-year-old social worker extraordinaire keeps young and active by happily doing charity work.

Kicking off the question and answer session Hsu said she was born “very, very poor” and the toughest part of her life was when she had to pick grass to eat as she was “very, very hungry”.

“It was at that moment I thought to myself that no one should ever go through what I went through,” she said.

When asked the secret to her longevity and good health, Hsu responded, “Ha, ha, ha! Make sure your heart is always happy”

She also said eating one raw egg every day for breakfast could be another reason for her good health.

“Once someone told me that raw egg is poisonous to which I replied ‘never mind, I thrive on poison’,” she said....

Having witnessed the suffering of the wounded during World War II, she recognised a calling to serve and at the age of 47, managed to convince the London Nursing College to accept her as a mature student.

She subsequently travelled around Europe to help the sick and needy and was even invited by German Jewish refugees to work in a hospital in Paraguay.

In 1961, Hsu arrived in Singapore to care for her ailing mother and founded the Home for the Aged Sick in Singapore. She has since made the republic her home.

In 2005, Hsu received the Special Recognition Award from the Singapore Government in recognition of her contribution to the country.

Hsu had the audience laughing with her sharp and witty answers to questions. When asked whether she had ever fallen sick, she quipped, “The sick demons forgot to visit me.”

Hsu also imparted words of wisdom to the audience by telling them that when somebody says anything unpleasant, just don’t listen.

“If someone also says they are not happy, go all out to make them happy because if you love everybody with all the love in your heart, then you’ll be happy, ha, ha, ha,” she laughed.

On death, Hsu said she normally does not console the relatives of the deceased but instead makes them laugh.

She told the audience how she got a lady whose uncle had died to laugh and sing along to a Cantonese kindergarten song, and soon had the audience singing, clapping and laughing.

Hsu also said whenever she was faced with a problem, she would try to solve it but if she could not, then she just accepted it.

To another question, she said she wasn’t born naturally caring but shared an incident that deeply affected and changed her. Her late mother once dug up potatoes to feed the family but gave away the entire pot to a starving beggar who arrived at their doorstep with a child.

“That was the day I learnt that to give what you have in your hand to others is a great blessing,” she said.

When asked how important religion was to her, Hsu said, “Nobody ever told me what a religion was”.

She cited an incident when a Buddhist man and a Christian lady were arguing and singing praises about their respective religions.

She told them, “Brother and sister, there’s just one door”.

She added: "Everyone is my brother and sister. My religion is Love."

----------------

© 1995-2010 Star Publications (Malaysia) Bhd (Co No 10894-D)

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - (0) Comment

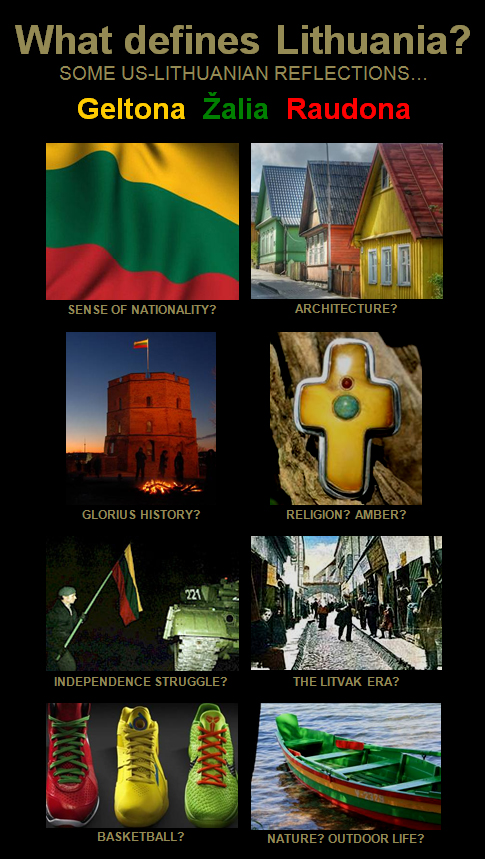

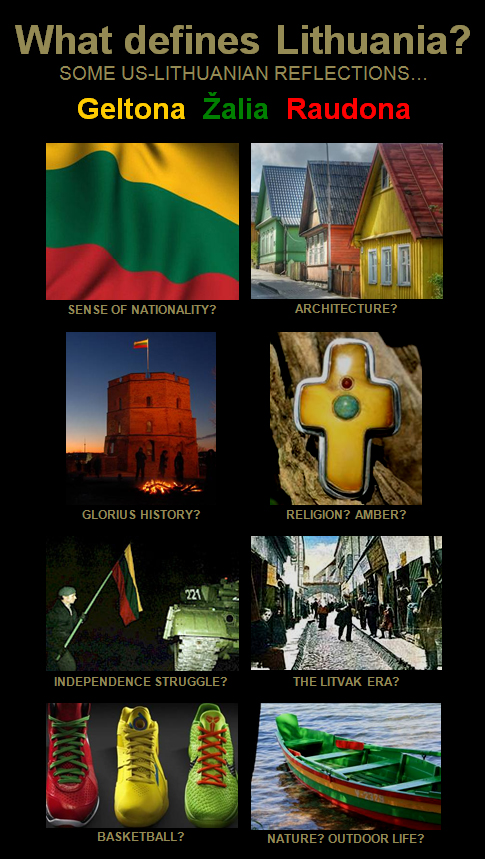

By Jennifer Virškus

A nation can be defined by several different characteristics; geographical location, language, a common history, cultural body, or race. The Lithuanian nation is defined by all of these. Lithuania has a language which is unique in the world and a culture that runs deep. It shares more than two centuries of its history with Poland, and few other nations have survived occupation by so many different groups. There are several types of nationalism; primordial, civic, organic, and liberal. Because of the lack of opportunity in Lithuania, young Lithuanians have recently tried to convince themselves that they want to “forget” their Lithuanian culture and move on to a new life in the West, but it is not possible. Lithuanians will always be Lithuanians whether they are in Lietuva or not. This is evident in the Lithuanian-American community, though they are clearly Americans, their Lithuanian identity stays with them. This is because Lithuanian nationalism is both geographic and organic, an entity to which all Lithuanians belong, as parts of a whole and independently of their will, choice or consciousness.

| Jennifer Virškus Jennifer Virškus is a Lithuanian-American freelance writer, photographer, graphic designer, skier, sailor, traveler, and current MFA Writing student at California College of the Arts. While living in Vilnius, she founded the Kalnu Ereliai Ski Team. You can read more of her writing about skiing, sailing, and Lithuania at her blog, One Way Ticket. |

|

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - (3) Comment

By Jennifer Virškus

A nation can be defined by several different characteristics; geographical location, language, a common history, cultural body, or race. The Lithuanian nation is defined by all of these. Lithuania has a language which is unique in the world and a culture that runs deep. It shares more than two centuries of its history with Poland, and few other nations have survived occupation by so many different groups. There are several types of nationalism; primordial, civic, organic, and liberal. Because of the lack of opportunity in Lithuania, young Lithuanians have recently tried to convince themselves that they want to “forget” their Lithuanian culture and move on to a new life in the West, but it is not possible. Lithuanians will always be Lithuanians whether they are in Lietuva or not. This is evident in the Lithuanian-American community, though they are clearly Americans, their Lithuanian identity stays with them. This is because Lithuanian nationalism is both geographic and organic, an entity to which all Lithuanians belong, as parts of a whole and independently of their will, choice or consciousness.

To be clear, I must define what I mean by geographic and organic nationalism. Geographic nationalism is a combination of primordial and social construct nationalism. That is to say, it is based on an ethnic identity and linked to a territory (O'Laughlin). It is distinctive, based on a unique culture, religion, and literature. At the same time, geographic nationalism is constructed by the elites, though not necessarily for their own benefit. In the case of Lithuania, it was constructed and propagated out of a feeling of repression, and the desire of the people to live in a democratic state they could call their own. Johann Gottfried Herder used the term nationalism while applying it to Volk, emphasizing the organic nature of a people. This goes beyond the primordial definition to suggest that nationalism is something ingrained in a people. Herder says that the nation is a natural creation and nationalities are not the product of men, rather the “work of a living organic force that animates the universe.” National culture is, as Herder puts it, closed to foreign eyes (Viroli). So, Lithuanian nationalism is primordial in the sense that it is based on an ethnic identity, language, and culture; it is socially constructed, or rather promoted, by the elite who want to form a Lithuanian state, and organic in that birth is the only way for one to become Lithuanian.

The Lithuanian state was founded in the 13th century by Grand Duke Mindaugas. Lithuania began to expand in the 14th century, and by the beginning of the 15th century Lithuania was one of the largest countries in Europe

FIGURE 1: The map of Lithuania in the 13th-15th centuries.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Lithuanian_state_in_13-15th_centuries.png

In 1569 Lithuania and Poland formed the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, ruled by an elected king who was also Grand Duke of Lithuania. During the partitions of Poland, Lithuania was largely annexed by the Russian Empire, disappearing from the map completely (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2: Lithuanian borders from the 13th century to today.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:LithuaniaHistory.png

Germany occupied Lithuania during the First World War until the Lithuanians declared independence on 16 February 1918. The Lithuanian Republic was proclaimed later that year and enjoyed a brief period of independence between the two World Wars. Independence lasted barely 20 years as the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact of 1939 allowed the USSR to take control of Lithuania. The Lithuanian Soviet Socialist Republic was proclaimed on 21 July 1940. The Germans occupied Lithuania again from 1941-1944. The Red Army returned in 1944, deporting mass numbers of Lithuanians to Siberia. Small groups of anti-Soviet activists continued to resist until 1952, though, all political parties were disbanded and the country was ruled exclusively by the Lithuanian Communist Party. Gorbechev’s policy of glasnost during the 1980’s allowed Lithuanian nationalism—kept alive by underground and exile groups—to resurface in the reformist climate. Sajudis, the Lithuanian Movement for Reconstruction, was established in 1988. On 11 March 1990, Vytautas Landsbergis declared the independence of Lithuania from the Soviet Union. After a military intervention and a bloody attempt by the Soviets to reclaim the Vilnius TV Tower, the USSR council also recognized the independence of Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia. Today, Lithuania is a republic-parliamentary democracy, with Dalia Grybauskaitė serving as President and Head of State

FIGURE 3: Lithuania today.

To choose one event in which Lithuanian nationalism originated is impossible. Rather, it was the combination of so many centuries of repression which gradually built nationalism to its current strength. We can, however, establish the roots of Lithuanian nationalism, but to do so, we must first establish national identity by looking at Lithuania’s historical foundations that have lasting ethnic bonds and language, which in turn reflect self-identification. “Heroic” self-perceptions are shaped by the collective memory of the strength of the Grand Duchy (Kavolis 1991). Certainly, the fight for independence from Russia and then Germany during the First World War—and most recently, from the Soviet Union—play a major role. It is often the repression of a nation which becomes a rallying point for nationalism; this is certainly true in the case of Lithuania. Modern national identity is also encouraged by contemporary social and political changes. The opportunity to separate from the Soviet Union and the risk-taking courage of the Lithuanians has not only helped to transform Lithuania, but also re-enforced their own national identity. Lithuanians can take pride in the fact that their provincial struggle gained the attention of the world and paved the way for many other nations on the road to independence.

The role of language, religion, monuments, and music cannot be underestimated in determining the origin of nationalism in Lithuania. The Lithuanian language draws its roots from Sanskrit. It is historically and linguistically important since it retains most of its archaic Indo-European forms. This is due to the fact that during the Polish-Lithuanian dynasty, Polish was the preferred tongue, and during Russian occupation a policy of “russificaiton” insisted that Russian be used in daily life. Though the underground journal, Aušra (the Dawn), created by Jonas Basnavičius, brought the Lithuanian language en vogue among Lithuanian intellectuals, the language developed little until the first Lithuanian independence of 1918 when it could finally be spoken openly. The language quickly became a strong source of pride as more and more Lithuanians began to learn and speak the language. John Locke describes Lithuanian national identity as “national language and self-dedication.” In his autobiography, Lithuania Independent Again, former Lithuanian president, Vytautas Landsbergis, reflects on the lives of his grandfathers, Gabrielius Landsbergis and Jonas Jablonskis, who worked together on the staff of Vilniaus Žinios (The Vilnius News), the only legal publication in the Lithuanian language at the turn of the century. Gabrielius’ family had been polonized and he only began to learn Lithuanian after entering high school. As he embraced the language, he became “firm and enthusiastic in his belief that he was a Lithuanian” (Landsbergis 2000). The growing nationalist movement was solidified as the geographical region of Lithuania was defined by its language. Aušra is an instance in which the elite was attempting to construct Lithuanian nationalism to inspire a move toward independence, however in doing so, led many Lithuanians to discover and embrace their language and the ethnic identity that accompanied it, having a lasting effect on nationalism today.

In addition to inspiring the use of the Lithuanian language, Aušra, is also considered the organ of Catholic Nationalism (Welch). The Polish-Lithuanian Dynasty was surrounded by Lutheranism to the West and North, and Russian Orthodoxy to the East. Together with the language, the Catholic faith became something that set the Lithuanians apart from their neighbors. National independence was the long-term goal, but Aušra rejected revolutionary activity, concentrating on preserving a nationally conscious and morally strong people, which it said was a precondition for statehood. It proposed a state similar to Israel where citizenship is based on the primordial elements of Lithuanian nationality and the Catholic religion (Welch 1983). Catholicism became so intertwined with Lithuanian identity, that during the interwar years to be Lithuanian was to be Roman Catholic (Donskis 2002). Here we have an example of nationalism being tied to an element already ingrained in Lithuanian society. Lithuanians were already Catholic, what changed in the first part of the twentieth century is that suddenly being Catholic, and Lithuanian, was something to be proud of.

FIGURE 4: Kryžiu Kalnas (the Hill of Crosses), near Šiauliai.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Hill-of-crosses-siauliai.jpg

Many monuments in Lithuania that promote nationalism have been created out of ties to the Catholic church. Most notably, Kryžiu Kalnas (the Hill of Crosses), near Šiauliai. A Lithuania pilgrimage center, Kryžiu Kalnas is a small hill where many hundreds of thousands of crosses have been placed to represent Christian devotion and as a memorial to Lithuanian national identity. This monument dates to the 14th century and is an example of peaceful resistance to oppression. Soviet tanks tried to destroy it on three separate occasions, leveling the monument during the night and either burning the crosses or turning them into scrap metal. Each time, crosses reappeared within days. Today it is an international pilgrimage site of mystical proportions, home to hundreds of thousands of crosses.

One can also think of the Lithuanian flag (Figure 5) as a monument to the Lithuanians who fought and died for the freedom of their country. The flag, adopted on 19 April 1918, consists of three horizontal stripes of yellow, green and red, the three colors most used in traditional weaving. The yellow represents the fertile fields of Lithuania, golden with ripe rye, wheat and flax. The green is a symbol of the nation’s vitality, and the red is a monument to the blood shed in defending the freedom of the homeland (Blavasciunas). All the elements of Lithuanian nationalism are represented in the flag: the organic yellow and green of the life that continues to grow, social construct references to the blood shed—a rallying point which the elites can use to promote nationalism—and the primordial element of the traditional colors used.

FIGURE 5: The Lithuanian flag.

Like monuments, music plays an important role in the expression of Lithuanian nationalism, most importantly, the work of Mikalojus Konstantinas Čiurlionis. Čiurlionis worked at the end of the 19th century helping to spawn nationalism with his symphonic poems which speak of the beauty of Lietuva. His two most important works, Jūra (The Sea) and Miške (The Forest) describe the two most prominent features of Lithuanian geography. The sea was an important resource for Amber as well as being valuable for trade with Scandinavia and Western Europe. The forest was the setting of most of Lithuanian folklore and pagan traditions, which are still practiced today. Čiurlionis’s work is a musical illustration of ancient ritual, religious devotion and national nostalgia, tying Lithuanian national identity directly to the land.

The national anthem (Figure 6) written by Dr. Vincas Kudirka contains references not only to national themes, but also to “the paths of virtue” (Kavolis). Kudirka did not intend for his poem, “Tautos Hymnas” (“National Hymn”), which espoused a love for Lithuania, to become the national anthem (Blavasciunas), yet it also includes all the elements of the origin of Lithuanian nationalism already mentioned above. The first line, “Lietuva, tėvyne mūsų, tu didvyrių žeme!” (“Lithuania, my homeland, land of heroes!”) makes the geographical connection, while the rest of the poem goes on to glorify Lithuania’s history and virtue. It does not mention revolution; on the contrary, it speaks only of the moral good of the Lithuanian people who have “light and truth” guiding their steps. These are certainly primordial elements; they come straight out of historical Lithuanian culture and values. The anthem is organic as it refers to Lithuania’s “children” working for the good of their native land. This implies the land upon which they were born—going back to Herder's argument that national identity is correlated to one’s birthplace—is integral to their identity.

During the Soviet Occupation, attempts to unite the USSR meant not only “russificaiton” but the outright banning of everything Lithuania had to be proud of; the language, Catholicism, music—in particular folk music—and public celebration of national festivals. Many monuments were destroyed and churches were turned into science museums. Hélène Carrère d'Encausse asks the question in her book Decline of an Empire, “Has the Marxist ideology of human uniformity gained mastery over this diverse society in which for the first time in history it has taken root and come to power?” Soviet indoctrination had several effects. The older generation that had seen the capabilities of the Soviets were sufficiently scared to live quietly, not wanting to risk deportation. Small children were the easiest to indoctrinate, and many went on to join the Komsomol (Soviet Young Communist League). There was however a small group of students, particularly at the time of Stalin’s death, who were eager to rediscover the outside world and their own heritage. Vytautas Landsbergis belongs to this group, and he was fortunate enough to study under Jadvyga Čiurlionytė, sister to Čiurlionis. She had established, by her own efforts, a department of Lithuanian folk music at the Vilnius Conservatoire (Landsbergis 2000). Landsbergis went on to become an expert in the music of Čiurlionis, writing several books on his painting and music. Together with the work of Čiurlionis’s sister, Landsbergis was the founder of a revival in Lithuanian Nationalism in the 1950’s, inspiring his own generation, and generations to follow to the idea that Lithuania was something to be proud of, and worth defending.

Opposition to the Soviet regime in Lithuania stems mainly from national and religious sentiments (Welch); of course the two are directly related. As a response to the Soviet secularization of society, a religious movement was spawned based on the overtly religious society which existed before the occupation. Many who were categorized as “non-believers” during Soviet times were actually secret practitioners. Religion became a personally and privately expressed, rather than institutionally expressed, experience. The Catholic rights movement evolved to be a comprehensive campaign against secularization (Welch) which was aided by the visit of Pope John Paul II to Poland in 1979, a visit that deeply disturbed communist authorities across the Eastern Bloc. The Catholic church was in a better position to publicly promote a nationalist movement than a small group of individuals such as the one Landsbergis belonged to as the Soviets could not send the entire church to the Gulag. In her article, “Nationalism and Lithuanian Dissent”, Irene Welch discusses in depth the ethnographic clubs and underground publications such as Varpas (The Bell) and Laisvės Šauklys (The Herald of Freedom), which were part of the cultural movement that inspired attempts from underground political organizations such as the Lithuanian Revolutionary Liberation Front. These movements demanded a more aggressive opposition than the Catholic movement did. They were involved, like Landsbergis, in a rediscovery and preservation of the primordial elements of Lithuanian nationalism which had been attacked by the Communist Party and the KGB. Nationalism never died in Lithuania, but it is fair to say that it was difficult to express publicly.

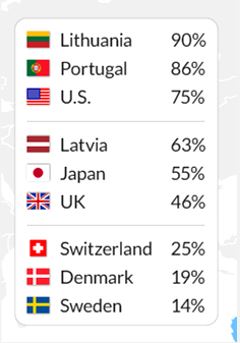

A study was done in the early 1980's about the retention of nationalism in second generation Lithuanian-Americans/Canadians in Chicago and Montreal (Figure 7). It found that there was a significant retention of culture and nationalism among young adults in their twenties. In his article, Virga Jelionis wrote that in identity formation, an individual draws both from the collective and self-identity. Jelionis proves that Lithuanian-Americans/Canadians draw not from the collective identity of either America or Canada, but rather from their Lithuanian heritage, and their own self-identity is not American or Canadian, but Lithuanian. The study is interesting because in Chicago, there is an established and definite neighborhood where most Lithuanians live and socialize, no doubt contributing to their own retention of culture, however, in Montreal where we see the same cultural trends, no such neighborhood exists. This shows us that retention of Lithuanian nationalism is deeper, not simply constructed through daily exposure. It is something that a person is born with, and cannot escape. Not only do we see that Lithuanian-Americans/Canadians are proud and comfortable in their ethnic community, but they prefer to engage in social activities with other Lithuanians and are very interested and concerned in the future of their homeland. In addition, the study shows that second generation Lithuanians still feel strongly that their own children attend Saturday school[1] and speak Lithuanian at home. While Lithuanian nationalism is based on primordial elements, Saturday school, scout groups, and dance troupes are ways in which nationalism is socially constructed and promoted. What is interesting and important to note, is that Lithuanian nationalism, at least in expatriate communities, is being constructed by the masses, both individually and collectively, rather than an educated elite. Nearly 90% of respondents answered either “yes” or “sometimes” to the question, “I am very conscious of, or preoccupied with, my [Lithuanian] nationality.” Very simply, Lithuanian nationalism, and being Lithuanian is important.

Nationalism in Lithuania today, is a very open experience, though, participation in Catholic activities is significantly lower. Communism succeeded in wiping out religious identity in the current twenty-something generation. This was the last generation born under the Soviet regime, and the current widespread trend away from the church in Europe also contributes. In 1991, there was no organized culture, and there was some debate about the path Lithuania should follow; join the pluralistic West, reaffirm certitudes of Lithuania’s own past, or seek to create a more universal post-totalitarian culture (Kavolis). One trend concerns the belief that individuals begin as members of a nation and that its leaders are "indistinguishable" from the nation, as the Lithuanian Democratic Party declared about Vytautas Landsbergis (Kavolis). It would seem that Lithuania is leaning toward reaffirming “certitudes of Lithuania’s past;” we see nearly daily celebrations of “memorial days, numerous re-inaugurations of destroyed monuments, reburials of exhumed bodies of Siberian deportees—expressions of the ancient belief that a person ultimately belongs to his or her native soil” (Kavolis). Kryžiu Kalnas is covered with more crosses than ever, and new statues are being erected constantly in honor of Lithuania’s children, fallen in her defense. The brave men and women who stood up to the tanks of the Red Army during the attempted capture of the Vilnius TV tower were given Lithuania’s highest Medal of Honor. Shortly after independence was declared, an important statue of Lenin was taken down to be replaced with that of a famous Lithuanian personality, Frank Zappa. Lithuanians can finally be openly and publicly proud of whom they are, where they come from, and the language they speak.

I consider myself a Lithuanian nationalist, though my heritage is only half Lithuanian and my upbringing was much more American than ethnic Lithuanian. We ate kugėlis and babka on Christmas morning, had Easter eggs my Grandmother painstakingly decorated with beeswax and natural dyes every year, and went to a Lithuanian church once in a while. But I didn’t speak Lithuanian, or go to Saturday school, nor did I attend summer heritage camp at Dainava. My exposure to Lithuanian culture was more subtle—my Grandmother’s accent, a word here or there. Sometimes my Dėdė[2] Balys would ask my brothers and I for clothes or old toys to send to “the cousins” in Lithuania. I didn’t know what it meant to be Lithuanian, but I knew it was something I belonged to and something I was proud of. My first public exhibition of nationalism came when I was twelve. I bought a pin representing the American and Lithuanian flags flying together. This was in 1989, and there was a stir in the Lithuanian community that soon Lietuva would be independent again. My nationalism was not constructed—it was hardly encouraged—it is primordial, based on a culture I still know so little about, and it is organic, something I was born with, and something that will continue to grow with me. Today Lietuva is independent, and going there means going home.

Bibliography

Carrère d'Encausse, Hélène. Decline of an Empire. HarperCollins, 1981.

Dobryninas, Aleksandras. “The Paradoxes of Freedom in Search of their Roots and Fruits.” Lituanus 39 no.4, (1993).

Donskis, Leonidas. Identity and Freedom: Mapping nationalism and social criticism in twentieth-century Lithuania. London: Routledge, 2002.

Hartman, Gary. “The Origins and Growth of Baltic Nationalism as a Force for Independence.” Lituanus 38 no. 3 (1992).

Jelionis, Virga. “Ethnic Identification: A Study of Second-Generation Lithuanians’ Retention of Culture.” Lituanus 28 no. 3 (1982).

Kavolis, Vytautas. “The Second Lithuanian Revival: Culture as Performance.” Lituanus 37 no.2 (1991).

Landsbergis, Vytautas. Lithuania Independent Again: The Autobiography of Vytautas Landsbergis. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2000.

O'Laughlin, John. GEOG 4712 “Politcal Geography.” University of Colorado at Boulder, 2002.

Ramunas Personal Pages. http://www2.omnitel.net/ramunas/Lietuva/

Taylor, Peter J. and Colin Flint. Political Geography. Essex: Pearson Education Limited, 2000.

Valentiejus, Algis. “Early Lithuanian nationalism: sources of its legitimate meanings in an environment of shifting boundaries.” Nations and Nationalism 8 no. 3 (2002): 315–33.

Welch, Irene. “Nationalism and Lithuanian Dissent” Lituanus 29 no.1 (1983).

|

Jennifer Virškus

|

|

Figure 6

Lithuania, my homeland, land of heroes!

Let your Sons draw strength from the past.

Let your children follow only the paths of virtue,

working for the good of their native land and for all mankind.

Let the sun banish all darkness from Lithuania,

with light and truth always guiding our steps.

Let the love of Lithuania burn in our hearts

and for the sake of our country let unity blossom.

Figure 7

LITUANUS

LITHUANIAN QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES

Volume 28, No.3 - Fall 1982

Editor of this issue: Antanas Klimas

ISSN 0024-5089

Copyright © 1982 LITUANUS Foundation, Inc.

ETHNIC IDENTIFICATION:

A STUDY OF SECOND-GENERATION LITHUANIANS' RETENTION OF CULTURE

VIRGA JELIONIS

Hofstra University

1-Strongly Agree 5-Strongly Disagree

Having a recognized place in my ethnic community is important to me.

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

|

|

__________________________________________________________________________________ |

|

|||||

|

36% |

19% |

36% |

- |

- |

9% |

(C) |

|

54% |

36% |

9% |

- |

- |

- |

(M) |

I gain feelings of self-worth from the position I occupy in my ethnic community.

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

|

|

___________________________________________________________________________________ |

|

|||||

|

36% |

27% |

19% |

9% |

- |

9% |

(C) |

|

45% |

27% |

19% |

9% |

- |

- |

(M) |

I feel most satisfied when I am engaged in social activities with other Lithuanians.

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

|

|

___________________________________________________________________________________ |

|

|||||

|

36% |

45% |

9% |

- |

- |

9% |

(C) |

|

27% |

36% |

27% |

9% |

- |

- |

(M) |

I am interested in the future of the Lithuanian homeland.

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

|

|

__________________________________________________________________________________ |

|

|||||

|

63% |

9% |

19% |

- |

- |

9% |

(C) |

|

45% |

19% |

36% |

- |

- |

- |

(M) |

I feel most satisfied when I am engaged in activities within the Lithuanian community.

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

|

|

__________________________________________________________________________________ |

|

|||||

|

27% |

36% |

27% |

- |

- |

9% |

(C) |

|

27% |

36% |

19% |

1 9% |

- |

- |

(M) |

I feel it is important that Lithuanian-(Americans/Canadians) visit Lithuania at least once in their lifetime.

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

|

|

__________________________________________________________________________________ |

|

|||||

|

45% |

9% |

1 9% |

19% |

- |

9% |

(C) |

|

63% |

9% |

27% |

- |

- |

- |

(M) |

I feel most satisfied when I am in the circle of my Lithuanian friends.

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

|

|

__________________________________________________________________________________ |

|

|||||

|

36% |

19% |

36% |

9% |

- |

- |

(C) |

|

27% |

27% |

27% |

- |

19% |

- |

(M) |

I feel it is important that Lithuanian-(American/Canadian-an) children attend Saturday school.

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

|

|

________________________________________________________________________________ |

|

|||||

|

63% |

- |

19% |

- |

9% |

9% |

(C) |

|

63% |

19% |

19% |

- |

- |

- |

(M) |

I feel it is important that Lithuanian-(Americans/Canadians) respect their parents' wishes to speak Lithuanian in their parents' home.

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

|

|

________________________________________________________________________________ |

|

|||||

|

63% |

9% |

19% |

- |

- |

9% |

(C) |

|

36% |

45% |

9% |

- |

9% |

- |

(M) |

I would want my children to be raised in a Lithuanian environment (i.e. attend Lithuanian school, speak Lithuanian in the home, socialize with other Lithuanians, participate in Lithuanian organizations and clubs, etc.)

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

|

|

__________________________________________________________________________________ |

|

|||||

|

63% |

9% |

- |

9% |

9% |

9% |

(C) |

|

54% |

27% |

9% |

- |

9% |

- |

(M) |

It is important for Lithuanian-(Americans/Canadians) to stay together as a closely-knit group for the purpose of keeping the culture alive and growing outside the homeland.

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

|

|

__________________________________________________________________________________ |

|

|||||

|

54% |

19% |

27% |

- |

- |

- |

(C) |

|

54% |

36% |

- |

9% |

- |

- |

(M) |

Lithuanian-(Americans/Canadians) should speak Lithuanian amongst themselves.

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

|

|

__________________________________________________________________________________ |

|

|||||

|

9% |

45% |

19% |

9% |

9% |

9% |

(C) |

|

19% |

27% |

19% |

19% |

19% |

- |

(M) |

In order to keep the Lithuanian culture alive in North America Lithuanian-(Americans/Canadians) should participate as fully as possible in their own cultural community.

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

|

|

__________________________________________________________________________________ |

|

|||||

|

54% |

19% |

1 9% |

9% |

- |

- |

(C) |

|

27% |

54% |

- |

- |

19% |

- |

(M) |

It is important that other (Americans/Canadians) be made aware of the Lithuanians' fight for freedom for their homeland.

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

|

|

__________________________________________________________________________________ |

|

|||||

|

81% |

9% |

9% |

- |

- |

- |

(C) |

|

72% |

19% |

- |

9% |

- |

- |

(M) |

To be a Lithuanian-American/Canadian) means to carry responsibility to be politically active in the fight for Lithuania's freedom.

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

|

|

__________________________________________________________________________________ |

|

|||||

|

9% |

63% |

9% |

9% |

9% |

- |

(C) |

|

9% |

36% |

19% |

9% |

9% |

19% |

(M) |

I have a duty to educate others about the Lithuanian culture.

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

|

|

__________________________________________________________________________________ |

|

|||||

|

27% |

45% |

19% |

- |

9% |

- |

(C) |

|

19% |

19% |

63% |

- |

- |

- |

(M) |

Of those people whom you would call your friends what proportion are Lithuanian?

|

all of them |

nearly all of them |

more than half |

less than half |

none |

|

|

________________________________________________________________________________ |

|

||||

|

9% |

45% |

36% |

- |

9% |

(C) |

|

- |

45% |

9% |

45% |

- |

(M) |

I always celebrate Christmas Eve Supper (Lith. Kūčios) with my family.

|

Yes |

Sometimes |

No |

|

|

________________________________________________________ |

|

||

|

63% |

9% |

27% |

(C) |

|

100% |

- |

- |

(M) |

I always celebrate Lithuanian Independence Day (February 16th).

|

Yes |

Sometimes |

No |

|

|

_______________________________________________________________ |

|

||

|

36% |

27% |

36% |

(C) |

|

81% |

19% |

- |

(M) |

I celebrate February 16th by attending a Lithuanian function.

|

Yes |

Sometimes |

No |

|

|

_______________________________________________________________ |

|

||

|

54% |

19% |

27% |

(C) |

|

81% |

19% |

- |

(M) |

I always celebrate Easter with my family.

|

Yes |

Sometimes |

No |

|

|

_______________________________________________________________ |

|

||

|

45% |

27% |

27% |

(C) |

|

91% |

9% |

- |

(M) |

I attend Mass at a Lithuanian church only as an obligation I am fulfilling for my parents.

|

Yes |

Sometimes |

No |

|

|

_______________________________________________________________Ž |

|

||

|

19% |

19% |

63% |

(C) |

|

-% |

45% |

54% |

(M) |

Lithuanians should make themselves known by their Lithuanian names in all of their non-Lithuanian environments.

|

Yes |

Sometimes |

No |

|

|

________________________________________________________________ |

|

||

|

72% |

9% |

19% |

(C) |

|

81% |

9% |

9% |

(M) |

I believe the family is important in keeping our culture alive.

|

Yes |

No |

|

|

___________________________________________ |

|

|

|

91% |

9% |

(C) |

|

81% |

19% |

(M) |

I am very conscious of, or preoccupied with, my nationality.

|

Yes |

Sometimes |

No |

|

|

_________________________________________________ |

|

||

|

54 |

27 |

19% |

(C) |

|

45 |

54 |