THE VOICE OF INTERNATIONAL LITHUANIA

|

VilNews has its own Google archive! Type a word in the above search box to find any article.

You can also follow us on Facebook. We have two different pages. Click to open and join.

|

Featured black

LT sportsmen in USA

- Posted by - (2) Comment

Šarūnas Jasikevičius, during EuroBasket 2011.

Text: Vin Karnila

Mention the words Sport and LITHUANIA and the next word you hear is always BASKETBALL. While a number of Lithuanian players have gone on to careers in the NBA it may surprise you to find out that quite a few Lithuanian athletes have had successful professional careers in the U.S.A. in other sports as well. What may be even a little more surprising is that these athletes excelled in what are considered “American” sports. As an example, did you know that the two players that most people say were the greatest players in the National Football League were Lithuanians?

BASKETBALL

Basketball is the sport that has tied Lithuania and USA closest together, so let’s first introduce you to the Lithuanian basketball stars “over there”.

Sarunas Jasikevičius

In July 2005 Sarunas Jasikevičius signed a three year contact with the Indian Pacers of the NBA. The point guard, who won three consecutive Euroleague championships, agreed to a three-year deal with the Pacers. Back in 1998, he was a solid wing player with Maryland, known for his shooting and intelligent play. He went back to his native Lithuania and plied his skills in club ball in Europe, becoming one of the best at his position. Arunas said “European ball is getting closer to the level of the NBA. I don't feel I have to play there to prove myself as a player,“

Žydrunas Ilgauskas

After being drafted by the Cleveland Cavaliers, Žydrunas Ilgauskas was selected to play in the 1997-98 Schick All-Rookie First Team. He was named MVP of the game, totaling a game-high 18 points and 7 rebounds, during the 1998 NBA All-Star Weekend in New York. Zydrunas led the Cavaliers in 1997-98 in field-goal percentage and blocked shots, ranked 2nd in rebounds, and 3rd in scoring. Unfortunately, he missed the entire 1996-97 season after undergoing surgery on his right foot. Ilgauskas rebounded to be named to the Eastern Conference All-Star Team in the 2002-03 season.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Q-3z39HQwfg

Arvydas Sabonis

Arvydas Sabonis, now retired from the NBA, has been considered the best big man in the basketball world. In 1995 he said: "There's nothing left for me to prove in Europe or in the basketball world. Only the NBA remains."

But before that, he had been leading the Soviet national team to a gold medal at the 1988 Olympic Games in Seoul, South Korea. He also helped Lithuania to a bronze medal at the 1992 Olympics in Barcelona, and a second-place finish in the 1995 European Championships in Greece. In an 11-year professional career spent with club teams in the former Soviet Union and then in the Spanish League, Sabonis has led his squads to five league championships and has been named European Player of the Year four times by various publications. On August 20, 2010, Sabonis was inducted into the FIBA Hall of Fame in recognition of his great play in international competition.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rsG9oApZtVI

Šarunas Marčiulionis

Šarunas Marčiulionis was a deadeye jump-shooter and capable of ferocious drives to the basket. He was a 1988 Olympic Games Gold Medal Champion in Seoul with Arvydas Sabonis.

Marčiulionis started his pro basketball career with Statyba Vilnius in the USSR League, the forerunner of the VTB United League in 1981. Drafted by the Golden State Warriors in the 6th round of the 1987 NBA Draft. He moved to the NBA in 1989 and he played four years with the Warriors, finishing as the runner-up for the Sixth Man of the Year Award in both 1992 and 1993. Marčiulionis became one of the first Europeans to get significant playing time in the NBA, helping to lead the way for the internationalization of the league in the late 1990s. After missing a year and a half with a leg injury, he was traded to the Seattle Super Sonics in 1994, then traded to the Sacramento Kings in 1995, and he finished his NBA career with the Denver Nuggets in the 1996-97 season. Having a career hampered by injury, he was on brink of making a real impression on the league before getting hurt.

Sarunas is today known as a hotel owner in Vilnius, as Founder of the Basketball Funds in Lithuania and the USA, as Founder of a private Basketball School and the Lithuanian Basketball League. In April, 1998 Sarunas became Extraordinary and Minister Pleni Potenciary of the Embassy of the Republic of Lithuania in the USA, and in 1999 he founded North European Basketball League NEBL and became its Commissioner.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=schzjV2RiN4

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fumWbJomIS4

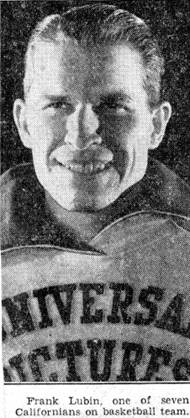

Frank Lubin / Pranas Lubinas

Frank Lubin / Pranas Lubinas (1910 - 1999) is often called the Grandfather of Lithuanian basketball as he promoted basketball in Lithuania and helped Lithuania win its second European championship in a row. He became an Olympic champion with the US team in 1936 in Berlin, and a European champion with the Lithuanian team in 1939 in Kaunas. He was born in Los Angeles in a family of Lithuanian emigrants, studied at UCLA University and was entered into the UCLA hall of fame in 1997. He played in AAU tournaments for about 30 years.

AMERICAN FOOTBALL

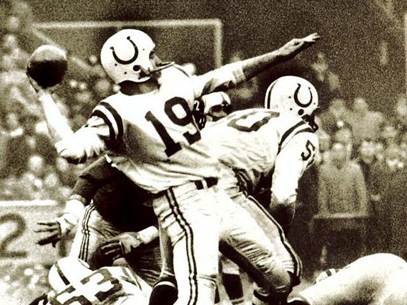

Johnny Unitas / Jonas Jaunaitis

Johnny Unitas / Jonas Jaunaitis (1933 - 2002) was a professional American football player in the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s. Unitas is considered by many to have been one of the best quarterbacks to ever play the game. He was the National Football League's most valuable player in 1957, 1959 and 1964. Unitas was born in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania in 1933. Johnny's father died when he was five years old and he was raised by his Lithuanian immigrant mother who worked two jobs to support the family.

Unitas set many passing records during his career. He was the first quarterback to throw for more than 40,000 yards, despite playing during an era when NFL teams played shorter seasons of 12 or 14 games (as opposed to today's 16-game seasons). His 32 touchdown passes in 1959 were a record at the time, making Unitas the first QB to hit the 30 touchdown mark in a season. His 47-game touchdown streak between 1956 and 1960 is a record that still stands and is considered by many the football equivalent of Joe DiMaggio's 56-game baseball hitting streak

Here is a short list of some of his other achievements:

Unitas held the record for most Pro Bowl appearances (10) by a quarterback until Brett Farve broke his record in 2009.

Unitas set the original standard for most wins as a starting quarterback with 118 regular season victories.

In 2004, The Sporting News ranked Unitas No. 1 among the NFL's 50 Greatest Quarterbacks, with Joe Montana No. 2.

Since 1987, the Johnny Unitas Golden Arm Award has been awarded to the top senior quarterback of the current year in college football.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=skVj2JppOOg

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0R-vbUvI6Bs

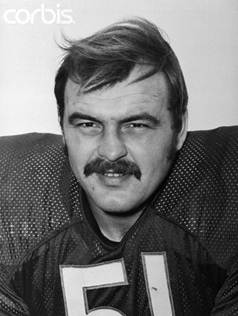

Dick Butkus

Dick Butkus is the man about whom the American sports press wrote; “It is possible that Butkus was the meanest, nastiest, fiercest linebacker to ever put on a helmet”. More than a quarter of a century after his retirement, there remains the Butkus image: the middle linebacker wrapping up a running back and viciously slamming him to the ground like an unwanted toy.

He was selected to eight Pro Bowls and was all-league six times. In his rookie season, Butkus led the Bears in tackles, interceptions, forced fumbles, and fumble recoveries, and regularly led the team in these categories throughout his career. Butkus recovered 27 fumbles in his career, a NFL record at the time of his retirement. He was one of the most feared players of his era and even appeared on the cover of Sports Illustrated in 1970 with the caption "The Most Feared Man in the Game." He had one of his most productive seasons in 1970 with 132 tackles, 84 assists, 3 interceptions and 2 fumble recoveries. He was forced to retire after multiple knee injuries in 1973.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zBumQdwc-tE

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sxR9qYSHt8U

BASEBALL

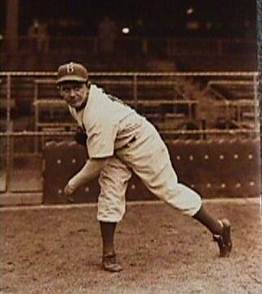

Vito Tamulis

Vito Tamulis (1911 - 1974) was born in Cambridge, MA. He was a sensation at Boston English High, pitching his school to the city championship in 1930. Turning down several college scholarship offers, Yankees scout Gene McCann signed him shortly before his 19th birthday. He worked his way up the Yankee chain, with a carreer culminating in 1934 with the Newark Bears. The Newark teams during the 1930 are rated as among the one hundred best minor league teams of all time. Vito Tamulis continued to live in the Nashville area until his death in 1974.

Joe Krakauskas

Joe Krakauskas (1915 – 1960) was a Major League Baseball pitcher who played for seven seasons. He played for the Washington Senators from 1937 to 1940 and the Cleveland Indians from 1941 to 1942 and 1946. He was 11-17 at his most active, with the 1939 Senators.

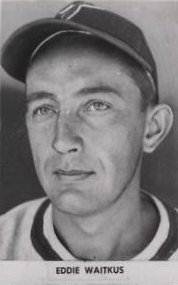

Eddie Waitkus

Eddie Waitkus (1919 – 1972) was the baseball player who inspired the movie, The Natural, starring Robert Redford as Roy Hobbs. This is a true story of a great baseball player, whose entire life was totally changed, because of an act of a single obsessed fan.

As the son of Lithuanian immigrants, Edward Stephen Waitkus grew up in Boston and served in the Pacific during World War II. His army service in some of the war’s bloodiest combat earned him four Bronze Stars. On the night of June 14, 1948, at the Edgewater Beach Hotel, Waitkus’s bright career took an infamously tragic turn. He received a cryptic note summoning him to meet a young fan, Ruth Steinhagen. When Waitkus entered her hotel room, she proclaimed, “I have a surprise for you,” and then she just as quickly shot him in the chest. He survived, and in his final summers he worked with youngsters at the Ted Williams baseball camp. Cancer claimed him in 1972, just days after his fifty-third birthday.

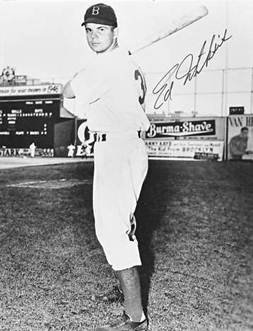

Eddie Miksis

Eddie Miksis (1926 - 2005) was 17 years old when he made his major-league debut on with Brooklyn. In 1953, he had a career-high with the Cubs and appeared in eight World Series Games -- five with the Dodgers in 1947 and three with the Dodgers in 1949. He was traded to the Cardinals in 1957 and finished up his career with Baltimore (1957-1958) and Cincinnati (1958). He lived in Philadelphia following his retirement from baseball.

Bill Sudakis

Bill Sudakis homered for Los Angeles in his first major league game. The Dodgers' third baseman in 1969, he was made a catcher and had won the everyday job in 1970 when he broke a finger. He became a versatile utilityman. More than one-third of Sudakis's hits were for extra bases.

BOXING

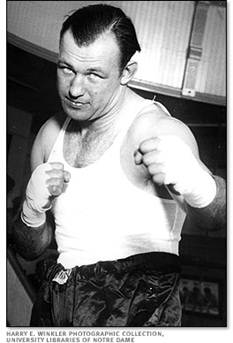

Jack Sharkey / Juozas Zukauskas

Jack Sharkey / Juozas Zukauskas (1902 - 1994) is the only man to have fought both Jack Dempsey and Joe Louis. But he may be best remembered for a pair of controversial title fights with German Max Schmeling. Sharkey fought for the vacant world title in 1930 against Schmeling but was disqualified for hitting below the belt in the fourth round. In 1932, he met Schmeling once again. The champion appeared to have a clear decision but the fight was awarded to Sharkey on a split decision. In his first title defense, Sharkey was knocked out by the mob-connected Carnera in the sixth round. As he did in 1931, Sharkey began by easily outboxing Carnera for the first five rounds. But he was floored with a right uppercut in round six and counted out. Many felt the fight was fixed but Sharkey denied the accusation until his death.

HOCKEY

Dainius Zubrus

Dainius Zubrus, born in Elektrenai, Lithuania, was drafted 15th overall in the 1996 NHL Entry Draft by the Philadelphia Flyers. He made his NHL debut on October 5, 1996, scoring a goal against the Florida Panthers. In his rookie season, he helped the Flyers reach the Stanley Cup final.

The Flyers traded him to the Montreal Canadiens on March 10, 1999. He registered his first career hat-trick on October 14, 2000, against the Chicago Blackhawks, and was traded by the Canadiens to the Washington Capitals on March 13, 2001.

During the 2005-06 season he posted a career-high 57 points. In the 2006–07 season, Zubrus continued his impressive form posting 52 points in 60 games before he was traded to the Buffalo Sabres February 27, 2007.

On July 3, 2007, Zubrus a free agent, signed a six-year, $20.4 million dollar deal with the New Jersey Devils. On November 23, 2008, Dainius Zubrus had one of the best offensive games in Devils history. Zubrus tied a team record with four goals to help New Jersey win its season-high fourth straight game, 7–3 over the Tampa Bay Lightning.

At 6 ft 5 in/1.96 m and 224 lb/102 kg. he is considered a “power forward” in the NHL. His size allows him to effectively use the body when needed but in spite of his size he is considered one of the most graceful skaters in the league along with being a good scorer and a very effective play maker.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cW66VP6rERY

Darius Kasparaitis

Darius Kasparaitis gave up his parental home in Elektrenai, Lithuania at the age of twelve to pursue a dream of becoming a professional hockey player which was an unusual route in a country that is dominated by basketball.

Kasparaitis played his first professional game for Dynamo Moscow, one of the premier teams in the Soviet Union, at the age of 16 during the 1988–89 season, and won the Soviet League championship with them in 1992.

He was drafted by the New York Islanders with the fifth overall pick in the first round of the 1992 NHL Entry Draft. Kasparaitis is known for his aggressive physical playing style and has led his teams in hits several times, including his rookie season, in 1992–93 NHL season with the New York Islanders. Kasparaitis has played for the New York Islanders, Pittsburgh Penguins, Colorado Avalanche and New York Rangers. Playing for Pittsburgh he scored a game seven overtime goal vs. Buffalo in 2001. Kasparaitis eventually wound up with the New York Rangers and during the 2005–06 season he served as their alternate captain.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CoyoJ-Un77Y

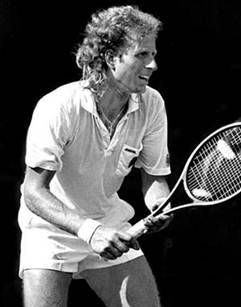

TENNIS

Vitas Gerulaitis

Vitas Gerulaitis (1954 - 1994) was a highly sucessful professional tennis player. Born in Brooklyn, New York, his biggest success was winning the men's singles title at the Australian Open in 1977, when he defeated John Lloyd in five sets.

Gerulaitis led the Pittsburgh Triangles to the World Team Tennis championship title at Pittsburgh's Mellon Arena in 1975. He also won the men's doubles title at Wimbledon in 1975. He was a singles semi-finalist at Wimbledon in both 1977 and 1978. In 1977, he lost a long Wimbledon semi-final to his close friend and practice partner, Björn Borg 6–4, 3–6, 6–3, 3–6, 8–6. In 1978, Gerulaitis won the year end championship WCT Finals for the World Championship Tennis tour, winning over Eddie Dibbs 6–3, 6–2, 6–1.

In 1979, Gerulaitis lost in men's singles finals at the US Open to fellow New Yorker John McEnroe in straight sets. He was a member of the United States team which won the Davis Cup in 1979. In the final, he won two singles rubbers as the US beat Italy 5–0.

Gerulaitis reached his third Grand Slam singles final in 1980, when he lost in the final of the French Open to Björn Borg in straight sets.

During his career, Gerulaitis won 25 top-level singles titles and 8 doubles titles. His career-high singles ranking was World No. 3 in 1978. He retired from the professional tour in 1986.

He died in a tragic accident in 1994 at age 40. While visiting a friend's home in East Hampton, Long Island, a malfunction in the air-conditioning system caused odorless poisonous carbon monoxide gases to seep through the house, leading to his death. Intensely proud of his Lithuanian heritage, Gerulaitis was well known for correcting reporters when they mispronounced his name.

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - (0) Comment

Chicago 26 – 28 April:

200 scholars meeting

to examine the Baltics

By Ellen Cassedy

More than 200 scholars from 15 countries are converging on Chicago – home to the largest population of Lithuanians outside of Lithuania itself – to present and respond to papers on Baltic history, literature, linguistics, political science, aesthetics, culture, sociology, psychology, economics, gender, anthropology, musicology, environment, education, and public health.

The 23rd biennial conference of the Association for the Advancement of Baltic Studies (AABS) opens April 26 at the University of Illinois. Organizers expect the conference to be the largest ever for the scholarly association, which was founded in 1968.

Members of the public are invited to attend the opening session, where the Lithuanian, Latvian, and Estonian ambassadors to the U.S. will speak on the conference theme: “The Global Baltics: the Next 20 Years.”

The session will take place at 1:30 p.m. at the Forum at the University of Illinois, 725 West Roosevelt Road, Chicago, IL 60608. For further information, contact Agnė Vertelkaitė, 312-397-0382, ext. 204, or e-mail: agne@ltconschi.org.

U.S. Senator Dick Durbin of Illinois, who is of Lithuanian descent, will address the three-day conference on Friday, April 27, on the topic of “The Unbreakable U.S.-Baltic Partnership.”

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - (2) Comment

Chicago 26 – 28 April:

200 scholars meeting

to examine the Baltics

By Ellen Cassedy

More than 200 scholars from 15 countries are converging on Chicago – home to the largest population of Lithuanians outside of Lithuania itself – to present and respond to papers on Baltic history, literature, linguistics, political science, aesthetics, culture, sociology, psychology, economics, gender, anthropology, musicology, environment, education, and public health.

The 23rd biennial conference of the Association for the Advancement of Baltic Studies (AABS) opens April 26 at the University of Illinois. Organizers expect the conference to be the largest ever for the scholarly association, which was founded in 1968.

Members of the public are invited to attend the opening session, where the Lithuanian, Latvian, and Estonian ambassadors to the U.S. will speak on the conference theme: “The Global Baltics: the Next 20 Years.”

The session will take place at 1:30 p.m. at the Forum at the University of Illinois, 725 West Roosevelt Road, Chicago, IL 60608. For further information, contact Agnė Vertelkaitė, 312-397-0382, ext. 204, or e-mail: agne@ltconschi.org.

U.S. Senator Dick Durbin of Illinois, who is of Lithuanian descent, will address the three-day conference on Friday, April 27, on the topic of “The Unbreakable U.S.-Baltic Partnership.”

|

Ellen Cassedy traces her Jewish family roots to Rokiskis and Siauliai. Her new book, We Are Here: Memories of the Lithuanian Holocaust, was published in March and will appear in Lithuanian in May. She lives in Washington, D.C. Visit her website at www.ellencassedy.com. |

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - (5) Comment

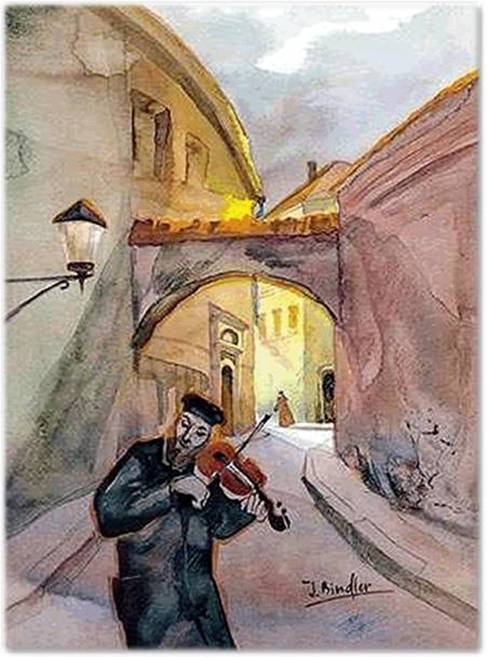

The Litvaks

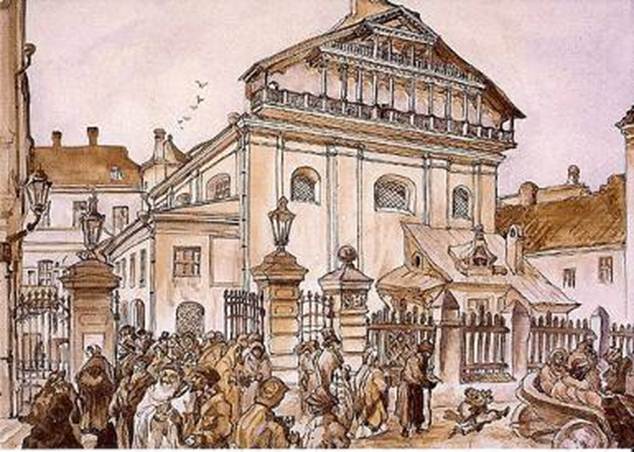

Watercolour by Izabele Bindler (1932 – 2003)

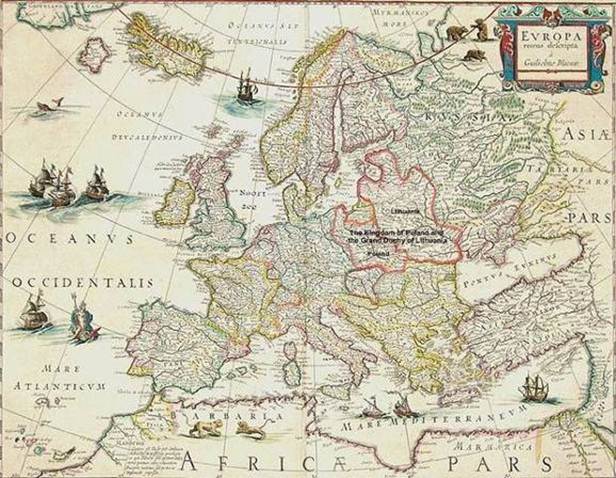

Jews trace their origins in Lithuania back to the days of Grand Duke Gediminas in the early 14th century, and by the late 15th century there were already thriving Jewish communities here. In time, Vilnius became known as the "Jerusalem of the North," a centre of Jewish religious learning. The Jews of Lithuania lived an intense Jewish life, and their role and influence in the major Jewish political and cultural movements were far greater than their numbers would have suggested. Vilnius became a prominent international, intellectual centre. Here there were once as many synagogues (totally 96) as churches—including the Great Synagogue, built in 1573, a vast complex of prayer spaces and schools.

Here were the innumerable yeshivas, with their famously erudite scholars (it was said that at one time there were 333 Jews of Vilnius who could recite the Talmud by heart). Here, in the 18th century, lived one of the greatest Talmudic experts of all time, the legendary Gaon of Vilna, to whom congregations from as far away as Portugal would send questions about matters of religious law or textual interpretation. Here, too, was the birthplace of the world-renowned Yiddish Scientific Institute; here was the Strashun Library, with its tens of thousands of volumes containing irreplaceable incunabula of Hebrew texts. Here flourished the most distinguished publisher of Hebrew books, the Widow & Brothers Romm, whose multi-volume Talmud, each page a masterwork of scholarship, composition, and design, was considered the pinnacle of Jewish publishing. Vilnius was also the greatest city of Diaspora learning, and at a time when others in Europe were effectively illiterate, all the Jews in Vilnius could read and write. This was so unusual that it provoked the invention of a brand-new word, "Vilner," meaning "an educated man with knowledge.

The below information about the Litvaks is from Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lithuanian_Jews

Background

Lithuanian Jews or Litvaks are Jews with roots in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania: (present-day Belarus, Lithuania, Ukraine, and the northeastern Suwałki region of Poland). The term is sometimes used, especially in Israel, to cover all Orthodox Jews who follow a "Lithuanian" (Ashkenazic and non-Hasidic) style of life and learning, whatever their ethnic background.

Lithuania was historically home to a large and influential Jewish community that was almost entirely eliminated during the Holocaust: see Holocaust in Lithuania. Before World War IIthere were over 110 synagogues and 10 yeshivas in Vilnius. Before World War II, the Lithuanian Jewish population was some 160,000, about 7% of the total population. Vilnius (then Wilno in the Second Polish Republic) had a Jewish community of nearly 100,000, about 45% of the city's total. About 4,000 Jews were counted in Lithuania during the 2005 census. There are still strong communities of Jews of Lithuanian descent around the world, especially in Israel, the United States, South Africa, Zimbabwe, and Australia.

The Grand Duchy of Lithuania

The adjective Litvish means "Lithuanian" (Latvian Jews were known as Lettish): the noun for a Lithuanian Jew is Litvak. Of the main Yiddish dialects in Europe, the Litvishe Yiddish(Lithuanian Yiddish) dialect was spoken by Jews in Lithuania, Belarus, and in the Suwałki region of northeastern Poland.

[edit]Ethnicity, religious customs and heritage

The characteristically "Lithuanian" approach to Judaism was marked by a concentration on highly intellectual Talmud study. Lithuania became the heartland of the traditionalist opposition to Hasidism, to the extent that in popular perception "Lithuanian" and "mitnagged" became virtually interchangeable terms. However, a sizable minority of Lithuanian Jews belong(ed) to Hasidic groups, including Chabad, Slonim, Karlin (Pinsk) and Koidanov. With the spread of the Enlightenment, many Lithuanian Jews became devotees of the Haskala (Jewish Enlightenment) movement in Eastern Europe pressing for better integration into European society, and today many leading academics, scientists and philosophers are of Lithuanian Jewish descent.

The most famous Lithuanian institution of Jewish learning was Volozhin yeshiva, which was the model for most later yeshivas. "Lithuanian" yeshivas in existence today include Ponevezh,Telshe, Mir, Kelm, and Slabodka. In theoretical Talmud study, the leading Lithuanian authorities were Chaim Soloveitchik and the Brisker school; rival approaches were those of the Mir and Telshe yeshivas. In practical halakha the Lithuanians traditionally followed the Aruch HaShulchan, though today the "Lithuanian" yeshivas prefer the Mishnah Berurah, which is regarded as both more analytic and more accessible.

In the 19th century, the Orthodox Ashkenazi residents of the Holy Land were broadly speaking divided into Hasidim and Perushim, who were Lithuanian Jews influenced by the Vilna Gaon. For this reason, in modern day Israeli Haredi parlance the terms Litvak (noun) or Litvisher (adjective), or in Hebrew Litaim, are often used loosely to include any non-HasidicAshkenazi Haredi individual or institution. Another reason for this broadening of the term is the fact that many of the leading Israeli Haredi yeshivas (outside the Hasidic camp) are successor bodies to the famous yeshivot of Lithuania, though their present-day members may or may not be descended from Lithuanian Jewry. In reality, both the ethnic makeup and the religious traditions of the mitnagged communities are much more diverse.

History

Some sources claim that Jews began living in Lithuania as early as the 8th century. In 1388 they were granted a charter by Vytautas, under which they formed a class of freemen subject in all criminal cases directly to the jurisdiction of the grand duke and his official representatives, and in petty suits to the jurisdiction of local officials on an equal footing with the lesser nobles (szlachta),boyars, and other free citizens. As a result, the community prospered.

In 1495 they were expelled by Alexander Jagiellon, but allowed to return in 1503. The Lithuanian statute of 1566 placed a number of restrictions on the Jews, and imposed sumptuary laws, including the requirement that they wear distinctive clothing, including yellow caps for men and yellow kerchiefs for women.

The Khmelnytsky Uprising destroyed the existing Lithuanian Jewish institutions. Still, the Jewish population of Lithuania grew from an estimated 120,000 in 1569 to approximately 250,000 in 1792. After the 1793 Second Partition of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth Lithuanian Jews became subjects of the Russian Empire.

Lithuanian Jews in the Second World War

The Jewish Lithuanian population before World War II numbered around 220,000. During the German invasion of June 1941, 206,800 Jews were murdered by the Nazis and Lithuanian collaborators. Most of the Jews were taken into the woods to be shot in graves they were forced to dig themselves. Notable execution locations were in the Paneriai woods (see Ponary massacre) and the Ninth Fort .

Culture

Litvaks have an identifiable mode of pronouncing Hebrew and Yiddish; this is often used to determine the boundaries of Lita (area of settlement of Litvaks). Its most characteristic feature is the pronunciation of the vowel holam as [ej] (as against Sephardic [oː], Germanic [au] and Polish [oj]).

In the popular perception, Litvaks were considered to be more intellectual and stoic than their rivals, the Galitzianers, who thought of them as cold fish. They, in turn, disdained Galitzianers as irrational and uneducated. Ira Steingroot's "Yiddish Knowledge Cards" devote a card to this "Ashkenazi version of the Hatfields and McCoys." This difference is of course connected with the Hasidic/mitnagged debate, Hasidism being considered the more emotional and spontaneous form of religious expression.

The two groups differed not only in their attitudes and their pronunciation, but also in their cuisine. The Galitzianers were known for rich, heavily sweetened dishes in contrast to the plainer, more savory Litvisher versions, with the boundary known as the "Gefilte Fish Line."

Genetics

The Lithuanian Jewish population may exhibit a genetic founder effect. The utility of these variations has been the subject of debate. One variation, which is implicated in familialhypercholesterolemia, has been dated to the 14th century, corresponding to the establishment of settlements in response to the invitation extended by Vytautas the Great in 1388. A relatively high rate of early-onset idiopathic torsion dystonia in the population has also been identified as possibly stemming from the founder effect.

Jews in Lithuania today

Interest among descendants of Lithuanian Jews has spurred tourism and a renewal in research and preservation of the community's historic resources and possessions. Increasing numbers of Lithuanian Jews are interested in learning and practising the use of Yiddish.

The beginning of the 21st century was marked by conflicts between members of Chabad-Lubavitch and secular leaders. In 2005, Chief Rabbi Sholom Ber Krinsky was physically removed from the Synagogue by two men hired by the community's secular leader Mr. Alperovich, who then declared a new Chief Rabbi.

Among notable contemporary Lithuanian Jews are the brothers Emanuelis Zingeris (a member of the Lithuanian Seimas) and Markas Zingeris (writer), Arkadijus Vinokuras (actor, publicist), Gercas Žakas (football referee), Gidonas Šapiro-Bilas (pop-singer from ŽAS), Dovydas Bluvšteinas (music producer), Leonidas Donskis (philosopher, essayist), Icchokas Meras(writer), Grigorijus Kanovičius (writer), Aleksas Lemanas (singer), Rafailas Karpis (opera singer (tenor)), Šabtajus Kalmanovičius (businessman and alleged criminal mastermind), David Geringas (world-renowned cellist and conductor), Liora Grodnikaitė (opera singer (mezzo-soprano)).

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - (0) Comment

Cultivating Lithuanian unity world-wide:

What YOU can do!

Boris Vytautas Bakunas

By Dr. Boris Vytautas Bakunas, Ph. D., Chicago

A wave of unity swept the international Lithuanian community on March 11th as Lithuanians celebrated the 22nd anniversary of the Lithuanian Parliament’s declaration of independence from the Soviet Union. However, the sense of national unity engendered by the celebration could be short-lived.

Human beings have a strong tendency to overgeneralize and succumb to stereotypical us-them distinctions that can shatter even the strongest bonds. We need only search the internet to find examples of divisive thinking at work:

”50 years of Soviet rule has ruined an entire generation of Lithuanian.”

”Those who fled Lithuania during World II were cowards -- and now they come back, flaunt their wealth, and tell us ‘true Lithuanians’ how to live.”

”Lithuanians who work abroad have abandoned their homeland and should be deprived of their Lithuanian citizenship.”

Could such stereotypical, emotionally-charged accusations be one of the main reasons why relations between Lithuania’s diaspora groups and their countrymen back home have become strained?

As psychiatrist Dr, Aaron T. Beck and others have noted, accusatory remarks are often perceived as threats by those targeted for verbal attack. Recriminations follow and escalate into verbal shooting matches that solidify hostilities between individuals and groups that previously enjoyed friendly relations.

Although debate is an inevitable and even desirable characteristic of free democratic societies, inflammatory finger-pointing can undermine a country’s national cohesion, political stability, and economic development. As individuals, what can we do to curb the spiral of anger-promoting speech that has surfaced within the world-wide Lithuanian community?

Comments

Jon Platakis

A poignant article that touches on the root causes of bias and discrimination. Throughout Lithuanian history, the Lithuanian people showed unity, determination and resiliency to overcome 200 years of foreign occupations that, once again, resulted in a free and sovereign nation. Today, it is only through unity, determination and resiliency by Lithuanians, in Lithuania and abroad, that Lithuania can move forward and reclaim her place on the world stage.

Although, physically, Lithuanians may live oceans apart, pushing each other further away only hinders the progress of the Lithuanian nation. As this article points out, cultural promotion and exchange between all Lithuanians can solidify and preserve our national identity. Organizations, such as, the National Lithuanian Hall of Fame, and the newly established Lithuanian-American Theater "Viltis" seek to promote Lithuanian culture in America, and at the same time, reach out and recognize achievements of Lithuanians in Lithuania.

One only has to look at history to learn that peoples united for a purpose or cause will always achieve their goals.

![]()

Sandy

Very interesting

![]()

Mary Ellen Lloyd

Why would there be ANY political differences among Lithuanian-Americans, at least for those over age 40 who are fully Lithuanian?? Do actual Lithuanians who lived under communism support any party which proposes to do the same thing to America that Russia did to Lithuania?? HOW can there be political divisiveness among Lithuanians who were old enough to witness the terrors and the gulags?

![]()

Boris Bakunas

One of the outstanding features of VilNews is how it publishes articles highlighting the achievements of Lithuanians around the world as well as the harsh realities of the past.

In 2011, two highly-acclaimed novels about the horrors of Soviet oppression were published. "Between Shades of Gray" by Ruta Sepetys told the story of a fifteen-year-old girl who along with her family was exiled to Siberia. Both hard-cover and paperback editions of "Between Shades of Gray" hit the New York Times best-seller list..

Antanas Sileika's novel "Underground" depicts the armed resistance of the Lithuanian partisans against the Soviet invaders and their collaborators. "Underground's" Lukas, is based on Lithuania's most famous partisan, Juozas Luksa--Daumantas. :"Underground" was picked as on of the best novels in English published in 2011 by The Globe and Mail. I have heard that the United States edition of Sileika's novel will be published within a few weeks.

2011 also saw the publication of Ellen Cassedy's book "We Are Here," which recounts the author's personal quest to understand how the people of Lithuania -- Jews and non-Jews -- are dealing with the horrors of the Nazi and Soviet past in order to build a new and better future. Ellen was inspired to write her book when her uncle, a Holocaust survivor, gave her a slip of paper and said, "Read this."

All three books, written by children of Lithuanians who escaped execution or exile, are helping to acquaint English-speaking public with one of the most tragic and heroic periods of Lithuanian history. They will also help educate a new generation of Lithuanians about the long suppressed history of Lithuania during and after World War II.

I am very happy that The National Lithuanian Hall of Fame is playing such an active role in helping to publicize all three books. This new organization has already donated more than five thousand dollars to help Lithuanian film director Tomas Donela secure the film right to "Underground." It is also making great progress in getting "Between Shades of Gray" on the reading lists of American schools and doing all it can to promote "We Are Here."

How can there be any divisiveness among Lithuanians in regards the terrors of the Gulag and the Holocaust? I don't have an answer to that question. I only know that during my own long life I have encountered several. I've spoken to and interviewed Lithuanians who collaborated with Nazis and with Soviet Communists. I've heard expressions of anti-Semitism, and I've heard several Lithuanians express nostalgia for the "good old days" under Communism. Probably, I'll never fully understand the dark side of human nature. But I also spoke to former partisans, political prisoners, and those who endured Siberian exile. My hope is that as individuals we do all we can to overcome hatred in word and in deed and help each other when we can.

In this endeavor, perhaps we can learn from the example set by South Africa's Truth and Reconciliation Commission. As Archbishop Desmond Tutu has said, "“Forgiving is not forgetting; its actually remembering--remembering and not using your right to hit back. Its a second chance for a new beginning. And the remembering part is particularly important. Especially if you dont want to repeat what happened.”

Post a new comment

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

This is the story of Vanda and her family. A story similar to what happened to many families that were affected by World War II's terrible events on Lithuanian soil, a story about innocent children who wanted a normal childhood in their beloved homeland, but instead were hit hard by the horrors of war and the terrible atrocities committed by the Hitler and Stalin regimes. Vanda and her parents managed to escape before Stalin's Red Army laid its iron grip over Lithuania in 1944. They came to Germany and later to the United States. Vanda's aunt had no such luck; she was deported to Siberia and starved to death because she shared her food rations with other deportees.

Vanda with her husband, Vytautas Sliupas, in June 2010.

They live in California.

Photo: Aage Myhre

By Vanda Fabijonaviciute Sliupas

My family lived in northern Lithuania but not close to Kaunas where my uncle Ipolitas’ residence was, nor Siaulenai where my aunt Benyte lived with Vytukas and Reniukas and uncle Adolfas Petrauskas.

Adolfas Petrauskas was the principal of a primary school and aunt Benyte was a teacher. The Fabijonas family did not approve of my mother because she did not have any education. According to them my father Juozas married below his social level. Even though my mother took in sewing and knitting to supplement a policeman’s salary to cover the cost of our living and to pay for a part of the costs to educate uncle Ipolitas and aunt Liuda. Our paternal grandmother, two aunts and uncle Ipolitas ignored us completely.

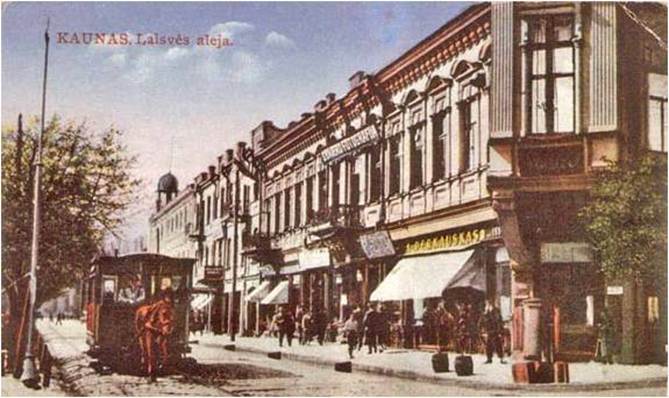

Then in 1938 Ipolitas’ wife committed suicide. We were invited to come to the funeral in Kaunas and this was the first time we met Vytukas, age 8 and Reniukas age 5. The adults were busy with the funeral arrangements and discussions of the tragedy, the four cousins played games and talked. My brother Romas, Vytukas and Reniukas formed a group. I was mostly by myself or talked to the housekeeper or anyone who was willing to spend some time with me. Until I got used to it, Vytukas looked sickly because of his small frame, red hair and very white complexion. The fifth cousin, orphaned Algiukas was not quite two years old and spent the time with grandmother. I remember being at the photographer’s and once walking in Kaunas on “Laisves Aleja” and eating the first sausage and a bun (something like a hotdog) on the street – which to me was a big treat.

1938: I remember being at the photographer’s and once walking in Kaunas on “Laisves Aleja” and eating

the first sausage and a bun (something like a hotdog) on the street – which to me was a big treat.

The next summer we were invited to join the families by a lake (can’t remember the name, but it was between Siaulenai and Siauliai). The four women stayed close to the house doing the chores and looking after Algiukas, but the four cousins (now even I was included) explored the lake, which formed a chain of seven lakes, and the forests around them. Those two weeks welded us together into a close unit and we loved being together and keeping our secrets to ourselves. From morning till night we played all kinds of games, ate our little lunches, slept on the moss under the ancient trees, fished when we felt like, swam and nobody told us to come home or even looked for us. But the time flew and we all went back to our homes after two weeks.

In June of 1940, Russia decided to occupy Lithuania –

our leaders fled to Western Europe or America

On the 3rd of September, 1939, the World War II started when Russia and Germany agreed to divide Poland between themselves. Then in June of 1940, Russia decided to occupy Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia to “protect us from ourselves”. Our leaders fled to Western Europe or America. Military and Police officers who stayed were imprisoned; some were shot immediately, others were deported to Siberia. Since my father worked in the Lithuanian police force, as soon as Russians came, he went into hiding. Mother took us to live with our maternal grandmother (baba) and her son uncle Vladas. The children were permitted to go to schools, but now had to learn Russian. At the beginning there was enough food and the common people who worked as manual laborers were exalted, but the educated or those who had some wealth were ridiculed and had to do heavy physical labor to prove they were just like any other person. To survive one had to have a food ration card. Very soon the stores emptied, especially in dry goods. Food still could be traded with farmers and everybody cultivated home gardens just to have something to put in the family’s dinner pot.

Since father was in hiding, the Communists tried to provoke us so they could put mother, Romas and me in prison, hoping that father would then give himself up. Several nights during that year, somebody tried to raise the Lithuanian flag on our roof to intimidate mother and uncle Vladas. But as soon as we heard them climbing the ladder, uncle Vladas would run outside and take the flag down.

June 1940: Russia invades Lithuania.

On June 14th, 1941, the deportation of 36,000 people began –

my aunt Benyte was deported to Siberia and starved to death

On June 14th, 1941, the deportation of 36,000 people began. The Soviets were not very selective during the first round of deportations; they came to the door, knocked, told the people they had 15 min. to pack and drove the families to the railroad station, loaded 60 or more of them into each cattle car with one bucket to serve as toilet. The NKVD (Soviet secret police) did not tell them why they were being deported, where they were taking them, for how long or how far. NKVD came to baba’s (my maternal grandmother) flat, searched for our family and for uncle Vladas, but could not find anybody and did not take baba either.

In Siaulenai it was the same procedure. They came to the school where the Petrauskas’ family lived. They found only aunt Benyte and cousin Renius/Renualdas (age about 8 yrs). Told her to pack and took them to the railroad station. Short time later uncle Adolfas Petrauskas came home and his neighbors told him that his wife and the younger son were arrested and taken to the railroad station to be deported. He ran to the station, but the soldiers would not let him search for his wife. He begged, he cried, he bribed them to be let on the platform in order to search for his wife and son. The soldiers thought he was out of his mind wanting to be deported, but he would not stop. Finally the soldiers let him go on the platform to search the cattle cars for his wife and son. As soon as he found them, he was pushed to another cattle car full of men, destined to Siberian forests, as a logger and he never saw his wife again.

After weeks of traveling Benyte reached her destination (I do not know the name of the location) deep in the Siberian wilderness and was assigned to work in food distribution. After couple years, around 1944, she was thrown into prison because she gave larger portions of bread to men who worked in the forest. In her cell she was deprived of food and starved to death; she was buried in the local cemetery.

In the 1950’s or ‘60’s the Russian government allowed families to bring the remains back to Lithuania and her mother-in-law made a trip to Siberia and brought her remains to Siauliai and reburied them in a cemetery lot. (Regina Petrauskas or the sons of Renualdas would know about the details of location or the year when each of the family members died.) After Renius’ mother died, Renius wrote to his paternal grandmother and eventually she traveled to Siberia and brought him back to Lithuania. After Stalin died in 1953, grandfather, Adolfas Petrauskas also was allowed to go to Lithuania and he is buried next to his beloved wife Benyte.

Lithuanians deported to Trofimovsk in the region of the Laptev Sea, Siberia, an area with permafrost

north of the Polar Circle. The photo is from 1949. These deportations started in 1941.

In 1942-43, a third of the deported people died, mainly children and elderly people.

Photo: The Museum of Genocide Victims, Vilnius, Lithuania.

Childhood in Russian and German occupied Lithuania 1940-1944

Now we come to my cousin Vytas/Vytautas Petrauskas. As I mentioned before, ever since childhood he always looked sickly. I do not think that he had TB, but his parents always were on the alert. At the time of their deportations Vytas was in Kaunas Sanatorium for lung diseases. As soon as uncle Ipolitas heard about what happened at the railroad station, he rushed to the hospital and brought Vytas from the sanatorium to his house.

After almost a year in hiding, mother received a message from my father that we immediately should take a train to Kaunas where uncle Ipolitas lived. I do not know who brought the message to mother, but mother packed small bundles of clothing and we three went to the railroad station. Luckily the night train was empty and no one checked our identities. We all knew that Germans were concentrating their forces on our borders to overrun us on their way to Russia and this was the only hope for us to survive.

When we reached Kaunas, mother, Vytas, Romas, and I were sent to a small village, about 30 km from Kaunas, where aunt Liuda was teaching primary school. This being summer holidays, the schoolrooms were empty. A helper brought in a lot of fresh cut grasses, some sheets, pillows and we had a nest to sleep in for the next four or five weeks. All of us slept in this one room, except aunt Liuda, grandmother Ona and orphaned Algiukas who already was 5 years old.

Now there were only the three of us to roam the surrounding fields. The soil was soft, white sand and the men dug out a shelter for us in case the war moved to this area. The floors we the children lined with ferns, the men put crossbars of saplings to form a roof and we had to pluck more ferns to cover our shelter. Luckily we did not have to use it as a shelter, but it made an excellent place for us to play in. I remember there still were wild strawberries hidden among the ferns and we managed to eat them to the last. The memory that stays with me is the suffocating aroma of the crushed fern fronds, but after a day or two we got used to it.

Then on the night of June 22nd, 1941, the war came to our area. We were close to the main highway to Kaunas and we were awakened by the sound of rolling military stock. There was no resistance by the Russians whatsoever, as if they never were there at all. The invasion came too late for the people who were being deported, the loaded cattle cars had enough time to be on their way to Siberia and the eastern coast of the Pacific Ocean. The women deportees were sent to the frozen fishing industry of the far Northeast, and the men were directed to the logging fields. The deportations continued from 1945 until 1953 and during that time 600,000 Lithuanians, Latvians, and Estonians were uprooted and moved to work in the frozen East.

The German army came, young men in clean uniforms were marching

to save us and we were willing to give them the best of what we had

June 1941: German Wehrmacht soldiers arrive in Lithuania, throwing the Russians out.

The morning of the 23rd June the German army came marching down the highway. And what a sight it was: young men in clean uniforms were marching to save us and we were willing to give them the best of what we had. Farmers gave them hams and rounds of cheese, housewives brought their cherry wine bottles, girls decorated them with flowers and kisses and the children marched alongside of them through the villages. You might say the Germans were occupying us just as the Russians did! That is true, but for the time being they saved thousands of people from being deported to Siberia. The Germans considered us Aryans and of the same blood as themselves. We hoped that we would be at least semi- independent. Also, as history proved, Stalin killed over 30,000,000 of his own people not counting the millions during the battles of war, whereas Hitler killed 10,000,000, mostly Jews, Gypsies, Poles and other Slavs. We were very small nations and could not fight either Russians or Germans; the only hope to survive was with the lesser evil. The euphoria lasted only three months until Lithuanians refused to execute the Lithuanian Jews and to join the German Army units or the SS battalions. Many young men had to go into hiding again or had to leave Lithuania for Sweden across the perilous Baltic Sea. Lithuania is the only country in the German occupied territories that never formed any SS units.

Otherwise life continued under a new occupation, except that food became very scarce and it was very dangerous to engage in any anti-German activities. German Gestapo terrorized the people whom they suspected. Political prisoners were usually sent to Dachau or Buchenwald concentration camps where about 300 Lithuanians were killed in one of them. Young men, who refused to serve in their armies, when caught, were sent to work in German military facilities which were regularly bombed by English and American planes, or to man the anti-aircraft batteries.

Vytas spent the winters with his paternal grandparents Petrauskas in Siauliai where he attended high school. As soon as summer vacations began, he would come to stay with us in Mazeikiai. The next three summers we spent roaming the surrounding areas, fishing in the river Venta and generally sticking our noses where they were not wanted. Nobody told us to stay home. Father had his office in one part of the house and he did not want to have us underfoot. Mother was busy with her usual money making extra work even though we did have a 20-something year local Russian girl helping in the house. The three of us slept in a very small room where two iron beds barely fit in it – boys slept in one bed and I in the other. Half the yard was fenced off and we all had pets there. I think Romas had a goose that followed him, Vytas had a rooster who ate from his mouth and I had a cat. If during our adventures we found an injured bird or a small animal, we always brought them home and tried to cure them, but did not have much success. We did not do anything spectacular, but Vytas came to us gladly and we all enjoyed each others’ company. I always considered to have had two brothers and when I had to explain myself, I used to get confused.

Emerging from an agricultural village, old Mazeikiai was mostly characterized by small wooden houses and shacks, surrounded by gardens where vegetables were grown, and livestock was held, mostly for private consumption. Water supply was from local wells, operated by hand pumps. Most streets were unpaved, and wooden sidewalks were used during winter periods in order to avoid walking in the mud and slush.

The summer of 1944 Vytas came as usual. The Russians, who were provided with arms and food by the Land Lease program of the USA, the Western front being opened and fought by the Americans and the Brits, were winning the war in the East and were on the move towards the Baltics. I remember Romas’ birthday (6-11) when father gave him a little gun. Vytas and Romas were so excited and were playing with it, fully loaded, when it went off and shot Romas through his left palm. For two days we said nothing either to mother or baba. The hand was swollen, but he still chopped the wood for the cooking stove and refused to face mama. But I became afraid and went to baba to tell her what happened. Baba came and scolded her daughter for not looking after us. Mama rushed Romas to the doctor who extracted the bullet and she told father not to scold him too much. The doctor gave some yellow powder (sulfur) and told Romas to put some on the wound every day to keep the infection in check.

Then the front moved closer and the adults panicked. Father and his assistant Mr. T. received a truck from the police department and with help of my uncle Vladas and both boys, packed most of our things in it, then drove to pick the assistant’s things.

In June of 1944 we left Mazeikiai towards the border with Germany

The morning of the 18th of June we left Mazeikiai towards the border with Germany – under no condition would one stay to face the Russians and a certain death. There were seven of us and I can’t remember how we all managed to fit in. The two men sat up front and the five of us lolled in the back of the truck holding onto the side belts. The German border was not that far from us and by the afternoon we stopped at a relative’s farm about 30 miles from the border, around Kretinga, but farther from the Baltic Sea. They were an elderly couple and very pleasant to us. After supper, the adults stayed inside the house discussing serious matters and the three of us were sent to the barn to sleep in the hay. Father and his assistant returned the next day to work in Mazeikiai, but we stayed at the farm for about six weeks.

The Eastern front was standing still and no new rumors circulated among the farmers. Since we might have to leave at any moment, we were restricted to stay at the farm. We played card games, often Vytas was sketching in his notebook, I read books found at the farm and Romas helped the farmer to fix some farm equipment. For us it was boring. The farmer had two horses, but we were permitted to ride them only in the yard. The first time Vytas rode, he almost killed himself. The yard was full of obstacles and lines stretched between trees and buildings for laundry and electrical connections. As he slowly rode, he hit one of the stretched wires under his chin and just hung there. The farmer came running, backed the horse and helped Vytas to climb down – for some time there was a mark where the wire hit his throat. Then a rumor came that our high school was moved to Ylakiai and was going to start the first week of September. Father came and took us to Ylakiai to another relative farmer. Father returned to Mazeikiai with the truck to his duties and to bring baba with him on his return. Since his assistant was wounded during an air raid by a fragment of a bomb in his hand, he did not have to go back to work. They stayed at a nearby farm. We had no clothes, because everything was in the truck and the truck went with father. The boys ran around in short pants but I had a light coat. Mother managed to get some fabric from the farmer and made long pants for Vytas and Romas. She bought a pig and salted for the winter and smoked some geese that the farmer sold. Everyone knew that when the Russian come, nothing will belong to farmers any longer and will be taken away from them. We waited for more than a month, but the high school never opened.

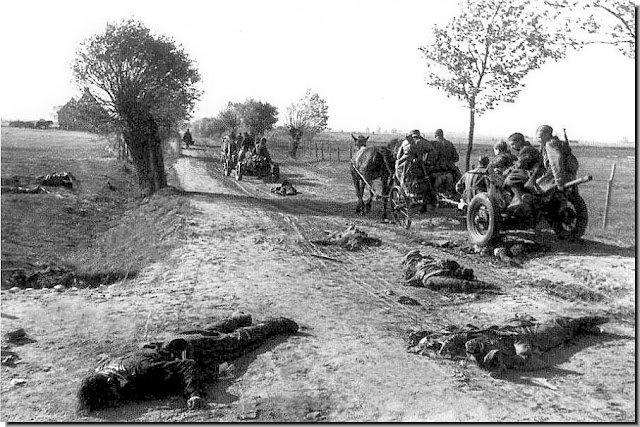

1944: German troops disembark in Lithuania.

Bombardments and shootings came from all sides, mother was panicking

On October 6th all hell broke loose: the front was not only moving, but running towards us. Bombardments and shootings came from all sides, mother was panicking, we could not get in touch with our father or grandmother – baba. It started getting dark and we did not know what to do. Mother told us each to pack our briefcases with items we wanted to take with us: Vytas took his sketches, Romas – stamps and I some knitting samples. After 23:00 hrs at night, father rushed in on a motorcycle without the truck and without our beloved baba – the German military police would not let him take the truck and baba was too old to ride on the motorcycle. He had stopped at his assistant’s place, they already had a wagon and a horse, so now father negotiated with the farmer and managed to get us a wagon with a horse. He just jumped, threw the one suitcase he had left with us into the wagon, then some preserved meats that mother had prepared, some flour, bread and we were off. The roads were full of refugees and Germans fleeing in cars and trucks, so we started straight across the fields and ditches. The bombardment went all around us. Fires were raging everywhere. Mother and the boys were running along the wagon, only father and I sat in it. The poor horse could not pull the wagon fast enough and out went the flour sack, then one barrel with the pork, then the other with smoked geese We were left just with one suitcase and a loaf of bread. After several hours we came to a major road that was not too badly congested.

Now all five of us climbed into the wagon. It was still dark, but all around the horizon fires were burning as villages and cities were disappearing from the face of the earth.

Just before dawn we passed Kretinga and the only thing we saw were flames leaping, jumping and rolling in huge rolling balls as the falling bombs ignited the wooden houses and the railroad yards. We continued towards Silute and by now there were three or four rows of wagons squeezing on the road. Suddenly couple platoons of Ukrainian Cossacks, serving in the German Army, in their bright uniforms on magnificent horses tried to cross our crowded road but could not breach it. They turned back to the fields and disappeared among the trees.

Suddenly, mother was gone. We started screaming and calling her name, but nobody answered.

Father gave the rains to Vytas and told him just to follow the other wagons in front of us. In front loomed the narrow Silute bridge that could accommodate only a single line of wagons. Father was gone for a minute or so, but could not find mother. Then, about 10 min. later, mother was back with us – she was separated from the wagon by people pushing and shoving each other to be across the Silute bridge soonest. We were a fifth or sixth wagon away from the bridge when suddenly the bridge with wagons and people on it exploded, bodies and concrete danced in the air for a minute or two, then slowly sank to the bottom of the ravine. The Russians were right on our heels and the Germans themselves blew up the bridge to prevent Russian tanks from crossing. Panic; people did not know what to do. Father and his assistant turned the horses and wagons around and we took a small road leading towards Kintai, Ventes Ragas and Kursiu Mares (Curonian Lagoon). Small groves of pines grew all around us. There were very many German soldiers who were encircled and trapped by their enemy with no escape.

1944: Soviet soldiers in carts, on their way westward, passing corpses of dead German soldiers.

Father’s assistant grew up in these environs and he spoke perfect German and knew the surroundings. We stopped at the staff tent and he started talking to the officer in charge. The officer said if there was any way to leave, he would evacuate his men, but there was not a chance. But he saw the exhausted children; I guess he must have had children himself. He said there was a small launch coming in the morning for the wounded soldiers and would sail as soon as the wounded were loaded, but he could not help us. Then father and the assistant said they both had revolvers, couple hundred rounds of bullets and would be willing to give them to him. He looked at the bullets, looked at us and asked for the horses also. Father gave him the revolvers and the bullets on his word that tomorrow morning he would give us a slip of paper to be admitted on the launch. They shook hands and we started looking for a farm where we could spend the night. The Germans were running short on ammunition for their last stand.

The first farm we came to was a well-run farm with apparently a good mistress, because everything was arranged as if they just left for church. Not even a cup was out of place and the beds were made. But the owners had fled. Vytas and Romas caught a goose, we all plucked its feathers, cooked it and ate it. We were starving. Father went to talk to his assistant while we dragged bedding from the house to a bomb crater. Soon father returned and we slept on the inside of the crater. Our parents and I woke up in the middle of the night when we heard footsteps on the gravel. Two Russian soldiers stood there looking at the five of us. The one sighed and said “let’s shoot them”, then the other replied “it’s just a family; let them sleep”. I did not speak Russian, but when they were gone, mother translated their conversation to us.

Early the next morning we drove back to the staff camp, the officer gave us a slip of paper and told where to leave the horses. We drove to the Ventes Ragas, the evacuation launch was already loaded, the boys carried our large suitcases and the seven of us sat on the floor among the wounded and dying solders wishing to escape the Russian entrapment and to make a new life in a strange country. The launch took us to Labiau (Labguva), East Prussia, and delivered us to a waiting Red Cross and some food. One has to admire how well organized the Germans were even at time of defeat. The first thing they made us do was take a communal bath, soak our hair in kerosene and scrape all the seams of our clothing with the same liquid to get rid of lice. But since we did not have another change of clothing we had to wear the same stinking garments. Then they put us on a train to Koenigsberg (Karaliaucius), (a city belonging to Lithuanian ancestors and given to Stalin during Yalta conference for 50 years, but even now it remains as a part in the Russian control). Then on another train to Dresden.

Father could not believe that the Germans would lose the war

Father and the assistant could not believe that the Germans would lose the war – they believed in secret weapons being developed (there were all kinds of rumors floating around giving hope to the refugees.) Therefore, father wanted to stay as close to Lithuanian border as possible. In Dresden we were advised by the Lithuanian Committee for Refugees to move to a small town to escape the nightly bombings. Mother and Mrs. Ona stayed in the railroad station to guard our belongings and the three of us were told to go and explore the city and come back in four hours. We were not enchanted with the environs around the railroad station. We visited a church with soaring towers and stared at the beautiful things displayed in the shop windows. Since we had no money to buy even a sweet bun, it became boring and we returned to mother. When the men came back, we had some bread and all slept on benches or on the floor, wherever we could find a free spot to lie down.

In the morning we climbed on the train for Grunwald, in Lower Silesia. There we ended up in a former restaurant that had one huge room and two toilets. When all the beds were assigned, there slept 60 people. Each had an iron bed with a thin mattress, sheet, pillow and a blanket. The adults were sent out to work in the city: mother became a nurse’s aide, Romas worked at a butcher shop (during the day one could go there and get a cup of very rich broth, but had to bring own bread), father and his assistant were assigned to the cemetery to grave digging, but Vytas and I stayed home and took care of our belongings. Mother received her meals at the hospital, Romas ate at work to his fill and he grew up very fast during those few months, but Vytas’s, father’s and my suppers depended on us. I think the landlady used to give us raw potatoes to fix for dinner. We could buy some bread, margarine and sometime marmalade on ration coupons and we still had some bacon in the large suitcase. The adults were paid small wages, but father saved most of it for tickets in case we had to move again; the Red Cross would not pay for our travel any more. The landlady had an old bicycle and gave it to Romas for his use.

1945: U.S Army arrives in Germany. Photo from 28 February 1945 near Frauwullesheim, Germany, after the First Infantry Division crossed the Roer River. It shows soldiers and vehicles on a rural road. The unit is identified as Company C, 1st Battalion, 18th Infantry Regiment, 1st Infantry Division, 1st U.S. Army.

Vytas and I practically lived on potatoes and pieces of bacon

As soon as we made beds and swept around them, we used to go to the surrounding forests and search for mushrooms so we could make them for father. Vytas and I practically lived on potatoes and pieces of bacon. Romas could not bring anything from the butcher shop because strict rules forbade him to take anything home. On weekends mother did the laundry and I had to darn everybody’s socks. There was a potbelly stove in our corner that helped to dry the heavy woolen socks father wore in his outside work. We spent two months in Grunwald, but the Russian front kept on moving closer to us day by day. As soon as father had saved enough money for tickets, he asked for permission to go to Dresden again to hear what the Lithuanian Committee for Refugees would advise us. This was right after Christmas 1944.

When we reached Dresden the city looked shabby in late December, cold with a strong wind from the Elbe River. This time we did not even want to go out of the station to look at the store windows and we stayed with mother and Mrs. Ona. Father and his assistant went to the Committee and were advised to go to Gotha, Thuringia, in central Germany. The trains were running full: going west with the wounded soldiers, and going east with the last of the German fighting men – boys from 17 yrs on, and men over 50 going east to fight the Russians. We could not get on any train with a suitcase and Romas' bicycle. We decided to leave them behind. The railroad supervisor issued a storage voucher to father. We covered our belongings with a tarpaulin in the corner of a platform and said goodbye to our bacon.

Arriving in the German town Gotha on New Year’s eve 1944-45

The trip westward took several days before we reached Gotha on the New Year’s eve 1944-45. The rails were being bombed almost every night and trains traveling east had priority, the westbound trains were continuously shunted to let them pass. We went to a small hotel and the men started looking for work. The city was already crowded with refugees and none of the adults could get a job of any kind. Without a job no one was willing to rent us a place to live and government would not issue ration coupons for food. And money was running out to pay for the hotel. Bombing alerts used to sound very often and we had to go to a shelter built in the side of a small hill in the middle of the city. It was very cold, and Vytas once fainted from hunger and I used to faint regularly. Finally, father and his assistant, who by now had become a good traveling companion and a friend, found jobs in a greenhouse outside the city and living facilities in two separate attics. We lived the month of January on ration cards and starved since we had no other source of food especially fat. Mother and we the three children became skeletons.

Most of our food had to go to father so he could do heavy manual work in the greenhouse. The German people had their gardens and were allowed to have rabbits. After a month of starvation, father decided to go back to Dresden and bring to us the suitcase with the bacon. He decided to take Romas with him and they left on the 12th of February. On the 14th of February we heard that Dresden was heavily bombed with incendiary bombs, was burning and completely destroyed. We did not know where father and Romas were, nor if they were still alive. Tears and despair filled our little rooms in the attics. There was nothing we could do, but pray and wait.

Gotha, Germany, where Vanda arrived with her family on New Year’s Eve 1944-45, became the first headquarters of the American Army in Germany, set up by General Dwight D. Eisenhower in April 1945, also as a Prisoner of War camp for captured German soldiers.

Only then they discovered that there was no more Dresden

When Father and Romas took the train east, it took them four days to reach the vicinity of Dresden. Only then they discovered that there was no more Dresden. The train stopped short of Dresden and everybody had to get off the train in a small suburban station. After traveling so long, father decided not to give up, but hike to Dresden and see if the railroad station was still standing.

Many people with bundled possessions were leaving the city to become refugees themselves. Father and Romas continued to walk for several hours through the destroyed, smoldering city, where the asphalt was still burning in places, corpses laying everywhere and the smell of burning flesh still filling the air. Finally they reached the railroad station. Its main building was completely destroyed: no roof, nor walls, but there were people around clearing the carnage and the debris of broken masonry and dead bodies. Father approached a station watchman and showed him the receipt for our luggage. The astonished man looked at our father and asked him if he could not see the destruction everywhere? But he looked at the receipt again and told father that his things were stored on platform #6. Father and Romas found the right platform and saw it held several tarpaulin covered mounds which were surrounded by debris and broken bricks. When they cleared the debris and lifted the tarpaulin they saw that their suitcase (which is still with us in USA as a souvenir) with the bacon was completely untouched and Romas’ bicycle was still there!

They loaded the heavy suitcase on the bicycle and started back to the suburban station: one pulling, the other pushing. Within three miles (5 km.) the bicycle collapsed and they started dragging the suitcase by the handle. But a good-hearted German with a wheelbarrow came along and offered help. Together they pushed the wheelbarrow with the suitcase to the suburban station the last 6 miles (10 km.). There were few passengers and no wounded soldiers going west, so father and Romas were able to take the suitcase with them on the train. Three days later they showed up at our rooms with the bacon and both of them uninjured and healthy. We really celebrated! The 45-day starvation in our family had ended and we managed to survive.

There was not much for us to do in Gotha. There were many more Lithuanians in the city; we used to have Sunday school and group meetings quite often, but made no friends – we lived too far from Gotha’s center. Like before, we played among the three of us.

U.S. General Eisenhower meeting with generals Patton, Bradley, and Hodges on an airfield somewhere in Germany during impromptu conference with supreme commander, March 1945.

Sad since our hopes of Americans turning against the Russians and beating them evaporated

On May 8th the World War II ended with German unconditional surrender and the American Army came to Thuringia. We rejoiced, but also were sad since our hopes of Americans turning against the Russians and beating them evaporated. What happened to all the promises made by President Roosevelt? Not only that, the USA and Britain agreed to Stalin’s demands and gave the three Baltic countries to the Russians!

We had no place to go, no place to call our own. But life went on under US Army control. There was a huge German depot close to us and the Americans opened the gates for everybody to take what they liked. On my way to the depot I saw my one and only execution – an American soldier shooting a civilian. At the depot there were not many things worth taking except a huge hill of green beans, which to the knowledgeable were un-roasted coffee beans, but no one knew that or took them. There were some plastic boxes. Father looked in the drawers of an office desk and found hundreds of food coupon books. Now we ate well, but had to stand in lines daily to purchase meat, sausages, sugar, flour or jams in every store. In each place we could use only five coupon books because we had to show our living permits also. But still it helped to fill our bellies.

One time we three found an unexploded canon shell about 16” long. Vytas and Romas decided to open it so they could have the cylinder. They started slowly knocking it on a stone and turning. I was scared since I had heard other boys being blown up doing such thing. But they would not desist and luckily succeeded to remove the explosive point. They took the cylinder home and father almost skinned them for being stupid. They collected a lot of shells of different guns, but never touched a big one again.

It was announced on the radio that in two weeks Thuringia would be given to the Russians. We had to prepare to run again. The landlady sold father a wheelbarrow and gave an old bicycle for the children to ride. In the end of May we started on foot south toward Bamberg, then west to Hanau near Frankfurt-am-Main in the Hessen province – a distance of over 150 miles (240 km). It was almost summer; the weather was nice and warm. The suitcase and blankets went into the wheelbarrow but water for drinking we carried along. Father and the boys pushed the wheelbarrow, taking turns every hour. The road through the mountains zigzagged all the time, but did not climb up, it was not hard, but a long and tiresome trip. Mostly I rode the bicycle, but often Vytas or Romas took over. The views were panoramic, majestic with small villages, churches dotting distant landscapes. A river ran along the road, but the water was very cold. When we passed a village, we bought bread, sausages and milk for each meal – were very grateful in having those coupon books. At the end of the day we usually washed in the river; nights we slept in the open each rolled in a blanket.

The first big city we passed was Wurzburg – from a distance it looked like a castle. It stood on top of a mountain surrounded by an ancient wall. We did not stop there since the Refugee Committee had told father that the Lithuanian high school will be opening in Hanau. We continued on our way. We descended from the Thuringia Mountains and now passed many towns, but almost all were partially destroyed by the war. It took us about 10 days to reach Hanau. The Displaced Persons camp, located outside the city, was in a former army barracks. After registering there we were assigned living quarters, ours happened to be on the fourth floor of a half destroyed building – the corridor was blocked and we could not go exploring in the ruins. There already were seven people living in the room and we added seven more. We received blankets, pillows and sheets, but beds the men had to build from scrap boards. First, the room was divided into half, each family isolated a place for themselves. Father and mother had one bed, Vytas and Romas another bed and a short bed for me. Then we were given straw mattresses. On our side was a belly stove for warmth and cooking. The toilets were on the other side of the corridor facing our door and it served as a laundry, bathroom and toilet. One learned not to be bashful because we had no privacy.

Vytas and Romas were assigned to the 4th Class, and I to the 2nd, of a Lithuanian Gymnasium (High school). Father worked as a truck mechanic, mother went to a sewing school. Food was provided 3 times daily. Now we had other interests and friends and the only time we spent together was in the evening, when the lights were out. Then all kinds of jokes, laughter and anecdotes floated in the room. We all joined the Lithuanian Scouts. Actually, I felt senior over the boys, because I was enrolled in Girl Guides in Lithuania at the age of six.

Then we received immigration papers and came to Chicago in April 1949

Vytas lived for two years with us in that room, then in 1947 he was permitted to immigrate to Chicago as an orphan and lived with uncle Purtokas’ family. There he reestablished the Lithuanian Eagle Scouts (Skautai Vyciai), was very active in meetings and camps.

Then we received immigration papers and came to Chicago in April 1949. In a week father and mother found work and rented a two-bedroom apartment in Town of Lake and Vytas came to live with us again. We had missed each other very much, so we could not stop talking, joking and laughing and fighting for the next two months. After College classes he worked at the Campbell Soup Co. Cannot remember where Romas worked. I worked at Goldenrod Ice Cream Co. and after work made dinners for the family, since mother used to come home very late. The money we made was for our education; the parents did not charge us for room, board and clothing. Vytas attended Wilson City College for 2 years, then moved to the University of Illinois in Urbana IL where he received his Architects Degree and started his own life.

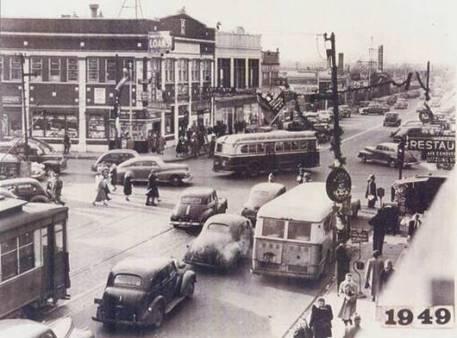

Chicago became Vanda’s new home in 1949. Here a photo from the Grand and Harlem

intersection, appears to be Christmas Season.

From NW Chicago history site.

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - (0) Comment

Memories of a prewar childhood in Lithuania – and an escape to the U.S.

This is the story of Vanda and her family. A story similar to what happened to many families that were affected by World War II's terrible events on Lithuanian soil, a story about innocent children who wanted a normal childhood in their beloved homeland, but instead were hit hard by the horrors of war and the terrible atrocities committed by the Hitler and Stalin regimes. Vanda and her parents managed to escape before Stalin's Red Army laid its iron grip over Lithuania in 1944. They came to Germany and later to the United States. Vanda's aunt had no such luck; she was deported to Siberia and starved to death because she shared her food rations with other deportees.

Vanda with her husband, Vytautas Sliupas, in June 2010.

They live in California.

Photo: Aage Myhre

KAUNAS 1938:

Vanda in 1938: “I remember being at the photographer’s and once walking in Kaunas on “Laisves Aleja” and eating the first sausage and a bun (something like a hotdog) on the street – which to me was a big treat.”

CHICAGO 1949:

Chicago became Vanda’s new home in 1949. Here a photo from the Grand

and Harlem intersection, appears to be Christmas Season.

>From NW Chicago history site.

- Bookmark :

- Digg

- del.icio.us

- Stumbleupon

- Redit it

- Posted by - (0) Comment

Cultivating Lithuanian unity world-wide:

What YOU can do!

Boris Vytautas Bakunas

By Dr. Boris Vytautas Bakunas, Ph. D., Chicago